The American Journal of Psychology/Volume 21/The Association Method/Lecture II

Lecture II

the familiar constellations

Ladies and Gentlemen: As you have seen, there are manifold ways in which the association experiment may be employed in practical psychology. I should like to speak to you to-day about another utilization of this experiment which is primarily of only theoretical significance. My pupil, Miss Fürst, M. D., has made the following research: she has applied the association experiment to 24 families, consisting altogether of 100 test persons; the resulting material amounted to 2,200 associations. This material was elaborated in the following manner: Fifteen separate groups were formed according to logical-linguistic standards, and the associations were arranged as follows:

| Husband | Wife | Difference | |||||

| I. | Co-ordination | 6 | .5 | 0 | .5 | 6 | |

| II. | Sub and supraordination | 7 | - | 7 | |||

| III. | Contrast | - | - | - | |||

| IV. | Predicate expressing a personal judgement | 8 | .5 | 95 | . | 86 | .5 |

| V. | Simple predicate | 21 | . | 3 | .5 | 17 | .5 |

| VI. | Relations of the verb to the subject or complement | 15 | .5 | 0 | .5 | 15 | . |

| VII. | Designation of time, etc. | 11 | . | - | 11 | . | |

| VIII. | Definition | 11 | . | - | 11 | . | |

| IX. | Coexistence | 1 | .5 | - | 1 | .5 | |

| X. | Identity | 0 | .5 | 0 | .5 | - | |

| XI. | Motor-speech combination | 12 | . | - | 12 | ||

| XII. | Composition of words | - | - | - | |||

| XIII. | Completion of words | - | - | - | |||

| XIV. | Clang associations | - | - | - | |||

| XV. | Defective reactions | - | - | - | |||

| Total, | - | - | 173 | .5 | |||

| Average difference | 173 | .5 | |||||

| = 11.5 | |||||||

| 15 | |||||||

As can be seen from this example, I utilize the difference to show the degree of the analogy. In order to find a base for the total resemblance I have calculated the differences among all of Miss Fürst’s test persons not related among themselves by comparing every female test person with all the other unrelated females; the same has been done for the male test persons.

The most marked difference is found in those cases where the two test persons compared have no associative quality in common. All the groups are calculated in percentages, the greatest difference possible being 200/15 = 13.3 %.

I. The average difference of male unrelated test persons is 5.9%, and that of females of the same group is 6%.

II. The average difference between male related test persons is 4.1%, and that between female related test persons is 3.8%. From these numbers we see that relatives show a tendency to agreement in the reaction type.

III. Difference between fathers and children = 4.2.

Difference between mothers and children = 3.5.

The reaction types of children come nearer to the type of the mother than to the father.

IV. Difference between fathers and their sons = 3.1.

Difference between fathers and their daughters = 4.9.

Difference between mothers and their sons = 4.7.

Difference between mothers and their daughters = 3.0.

V. Difference between brothers = 4.7.

Difference between sisters 5.1.

If the married sisters are omitted from the comparison we get the following result:

Difference of unmarried sisters = 3.8.

These observations show distinctly that marriage destroys more or less the original agreement, as the husband belongs to a different type.

The difference between unmarried brothers = 4.8. Marriage seems to exert no influence on the Association forms in man. Nevertheless, the material which we have at our disposal is not as yet enough to allow us to draw definite conclusions.

VI. The difference between husband and wife = 4.7. This number, however, sums up very inadequately the different values; that is, there are some cases which show a marked difference and some which show a marked agreement.

The description in curves of the different results follows.

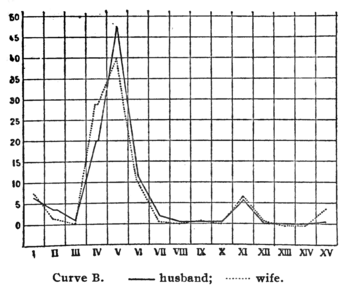

In the curves here reproduced I have marked above the number of associations of each quality in percentages. The Roman letters written below the diagram designate the forms of association indicated in the above tables (see above).

Curve A. The father (continued line) shows an objective type, while the mother and daughter show the pure predicate type with a pronounced subjective tendency.

Curve B. The husband and wife agree well in the predicate objective type, the predicate subjective being somewhat more numerous in the wife.

Curve C. A very nice agreement between a father and his two daughters.

Curve D. Two sisters living together. The dotted line represents the married sister.

Curve E. Husband and wife. The wife is a sister of the two women of curve D. She approaches very closely to the type of her husband. Her curve is the direct opposite of that of her sisters.

The similarity of the associations is often very extraordinary. I will reproduce here the associations of a mother and her daughter.

| Stimulus Word | Mother | Daughter |

| to pay attention | diligent pupil | pupil |

| law | command of God | Moses |

| dear | child | father and mother |

| great | God | father |

| potato | bulbous root | bulbous root |

| family | many persons | 5 persons |

| strange | traveller | traveller |

| brother | dear to me | dear |

| to kiss | mother | mother |

| burn | great pain | painful |

| door | wide | big |

| hay | dry | dry |

| month | many days | 31 days |

| air | cool | moist |

| coal | sooty | black |

| fruit | sweet | sweet |

| merry | happy child | child |

One might indeed think that in this experiment, where full scope is given to chance, individuality would become a factor of the utmost importance, and that therefore one might expect a very great diversity and lawlessness of associations. But as we see the opposite is the case. Thus the daughter lives contently in the same circle of ideas as her mother, not only in her thought but in her form of expression; indeed, she even uses the same words. What seems more flighty, more inconstant, and more lawless than a fancy, a rapidly passing thought? It is not, however, lawless, and not free, but closely determined within the limits of the milieu. If, therefore, even the superficial and manifestly most flighty formations of the intellect are altogether subject to the milieu-constellation, what should we expect for the more important conditions of the mind , for the emotions, wishes, hopes, and intentions? Let us consider a concrete example,—the curve A. (See above.)

The mother is 45 years old and the daughter 16 years. Both have a very distinct predicate type expressing personal judgment, and differ from the father in the most striking manner. The father is a drunkard and a demoralized creature. We can thus readily understand that his wife perceives an emotional voidness which she naturally betrays by her enhanced predicate type. The same causes cannot, however, operate in the daughter, for in the first place she is not married to a drunkard, and secondly life with all its hopes still lies before her. It is distinctly unnatural for the daughter to show an extreme predicate type expressing personal judgment. She responds to the stimuli of the environment just like her mother. But whereas in the mother the formation is in a way a natural consequence of her unhappy condition of life, this condition is entirely lacking in the daughter. The daughter simply imitates the mother; she merely appears like the mother. Let us consider what this can signify for a young girl. If a young girl reacts to the world like an old woman disappointed in life this at once shows unnaturalness and constraint. But more serious consequences are possible. As you know the predicate type is a manifestation of intensive emotions; emotions are always involved. Thus we cannot prevent ourselves from answering at least inwardly to the feelings and passions of our nearest environment; we allow ourselves to be infected and carried away by it. Originally the affects and their physical manifestations had a biological significance; i.e., they were a protective mechanism for the individual and the whole herd. If we manifest emotions we can with certainty expect to receive emotions in return. That is the sense of the predicate type. What the 45-year-old woman lacks in emotions; i.e., in love in her marriage relations she seeks to obtain from the outside, and it is for that reason that she is an ardent participant in the Christian Science meetings. If the daughter imitates this situation she does the same thing as her mother, she seeks to obtain emotions from the outside. But for a girl of 16 such an emotional state is to say the least quite dangerous; like her mother she reacts to her environment as a sufferer soliciting sympathy. Such an emotional state is no longer dangerous in the mother, but for obvious reasons it is quite dangerous in the daughter. Once freed from her father and mother she will be like her mother; i.e., she will be a suffering woman craving for inner gratification. She will thus be exposed to the greatest danger of falling a victim to brutality and of marrying a brute and inebriate like her father.

This consideration seems to me to be of importance for the conception of the influence of environment and education. The example shows what passes over from the mother to the child. It is not the good and pious precepts, nor is it any other inculcation of pedagogic truths that have a moulding influence upon the character of the developing child, but what most influences him is the peculiarly affective state which is totally unknown to his parents and educators. The concealed discord between the parents, the secret worry, the repressed hidden wishes, all these produce in the individual a certain affective state with its objective signs which slowly but surely, though unconsciously, works its way into the child’s mind, producing therein the same conditions and hence the same reactions to external stimuli. We know that association with mournful and melancholic persons will depress us, too. A restless and nervous individual infects his surroundings with unrest and dissatisfaction, a grumbler, with his discontent, etc. If grownup persons are so sensitive to such surrounding influences we certainly ought to expect more of this in the child whose mind is as soft and plastic as wax. The father and mother impress deeply into the child’s mind the seal of their personality, the more sensitive and mouldable the child the deeper is the impression. Thus even things that are never spoken about are reflected in the child. The child imitates the gesture, and just as the gesture of the parent is the expression of an emotional state, so in turn the gesture gradually produces in the child a similar feeling, as it feels itself, so to speak, into the gesture. Just as the parents adapt themselves to the world so does the child. At the age of puberty when it begins to free itself from the spell of the family, it enters into life with so to say a surface of fracture entirely in keeping with that of the father and mother. The frequent and often very deep depressions of puberty emanate from this; they are symptoms which are rooted in the difficulty of new adjustment. The youthful person at first tries to separate himself as much as possible from his family, he may even estrange himself from it, but inwardly this only ties him the more firmly to the parental image. I recall the case of a young neurotic who ran away from his parents, he was strange and almost hostile to them, but he admitted to me that he possessed a special sanctum; it was a strong box containing his old childhood books, old dried flowers, stones, and even small bottles of water from the well at his home and from a river along which he walked with his parents, etc.

The first attempts to assume friendship and love are constellated in the strongest manner possible by the relation to parents, and here one can usually observe how powerful are the influences of the familiar constellations. It is not rare, e.g., for a healthy man whose mother was hysterical to marry a hysterical, or for the daughter of an alcoholic to choose an alcoholic for her husband. I was once consulted by an intelligent and educated young woman of 26 who suffered from a peculiar symptom. She thought that her eyes now and then took on a strange expression which exerted a disagreeable influence on men. If she then looked at a gentleman he became embarrassed, turned away and said something rapidly to his neighbor, at which both were either embarrassed or inclined to laugh. The patient was convinced that her look excited indecent thoughts in the men. It was impossible to convince her of the falsity of her conviction. This symptom immediately aroused in me the suspicion that I dealt with a case of paranoia 1 rather than with a neurosis. But as was shown only three days later by the further course of the treatment, I was mistaken, for the symptom promptly disappeared after it had been explained by analysis. It originated in the following manner: The lady had a lover who deserted her in a very striking manner. She felt utterly forsaken, she withdrew from all society and pleasure, and entertained suicidal ideas. In her seclusion there accumulated unadmitted and repressed erotic wishes which she unconsciously projected on men whenever she was in their company. This gave rise to her conviction that her look excited erotic wishes in men. Further investigation showed that her deserting lover was a lunatic, which she did not (apparently observe. I expressed my surprise at her unsuitable choice and added that she must have had a certain predilection for loving mentally abnormal persons. This she denied, stating that she had once before been engaged to be married to a normal man. He, too, deserted her; and on further investigation it was found that he, too, had been in an insane asylum shortly before,—another lunatic! This seemed to me to confirm with sufficient certainty my belief that she had an unconscious tendency to choose insane persons. Whence originated this strange taste? Her father was an eccentric character, and in later years entirely estranged from his family. Her whole love had therefore been turned away from her father to a brother 8 years her senior; him she loved and honored as a father, and this brother became hopelessly insane at the age of 14. That was apparently the model from which the patient could never free herself, after which she chose her lovers, and through which she had to become unhappy. Her neurosis which gave the impression of insanity probably originated from this infantile model. We must take into consideration that we are dealing in this case with a highly educated and intelligent lady who did not pass carelessly over her mental experiences, who indeed reflected much over her unhappiness without, however, having any idea whence her misfortune originated.

These are things which inwardly appeal to us as matter of course, and it is for this reason that we do not see them but attribute everything to the so-called congenital character. I could cite any number of examples of this kind. Every patient furnishes contributions to this subject of the determination of destiny through the influence of the familiar milieus. In every neurotic we see how the constellation of the infantile milieu influences not only the character of the neurosis but also life’s destiny, in its very details. Numberless unhappy choices of profession and matrimonial failures can be traced to this constellation. There are, however, cases where the profession has been happily chosen, where the husband or wife leaves nothing to be desired, and where still the person does not feel well but works and lives under constant difficulties. Such cases often appear in the guise of chronic neurasthenia. Here the difficulty is due to the fact that the mind is unconsciously split into two parts of divergent tendencies which are impeding each other; one part lives with the husband or with the profession, while the other lives unconsciously in the past with the father or mother. I have treated a lady who, after suffering many years from a severe neurosis, merged into a dementia praecox. The neurotic affection began with her marriage. This lady’s husband was kind, educated, well to do, and in every respect suitable for her; his character showed nothing that would in any way interfere with a happy marriage. Despite that the marriage was an unhappy one merely because the wife was neurotic and therefore prevented all congenial companionship.

The important heuristic axiom of every psychanalysis reads as follows: If a neurosis springs up in a person this neurosis contains the counter-argument against the relationship of the patient to the personality with which he is most intimately connected. If the husband has a neurosis the neurosis thus loudly proclaims that he has intensive resistances and contrary tendencies against his wife, and if the wife has a neurosis the wife has a tendency which diverges from her husband. If the person is unmarried the neurosis is then directed against the lover or the sweetheart or against the parents. Every neurotic naturally strives against this relentless formulation of the content of his neurosis, and he often refuses to recognize it at any cost, but still it is always justified. To be sure the conflict is not on the surface but must generally be revealed through a painstaking psychanalysis.

The history of our patient reads as follows:

The father had a powerful personality. She was his favorite daughter and entertained for him a boundless veneration. At the age of 17 she for the first time fell in love with a young man. At that time she had twice the same dream, the impression of which never left her in all her later years; she even imputed to it a mystic significance and often recalled it with religious dread. In the dream she saw a tall, masculine figure with a very beautiful white beard; at this sight she was permeated with a feeling of awe and delight as if she experienced the presence of God himself. This dream made the deepest impression on her, and she was constrained to think of it again and again. The love affair of that period proved to be one of little warmth and was soon given up. Later the patient married her present husband. Though she loved her husband she was led continually to compare him with her deceased father; this comparison always proved unfavorable to her husband. Whatever the husband said, intended, or did, was subjected to this standard and always with the same result: “My father would have done all this better and differently.” Our patient’s life with her husband was not happy, she could neither respect nor love him sufficiently; she was inwardly dissatisfied and unsatiated. She gradually evinced a fervent piety, and at the same time there appeared a violent hysterical affection. She began by going into raptures now over this and now over that clergyman, she was looking everywhere for a spiritual friend, and estranged herself more and more from her husband. The mental trouble made itself manifest after about a decade. In her diseased state she refused to have anything to do with her husband and child; she imagined herself pregnant by another man. In brief, the resistances against her husband which hitherto had been laboriously repressed came out quite openly, and among other things manifested themselves in insults of the gravest kind directed against her husband.

In this case we see how a neurosis appeared, as it were at the moment of marriage, i.e., this neurosis expresses the counter-argument against the husband. What is the counter-argument? The counter-argument is the father of the patient, for she verified daily her belief that her husband was not equal to her father. When the patient first fell in love there also appeared a symptom in the form of a very impressive visionary dream. She saw the man with the very beautiful white beard. Who was this man? On directing her attention to the beautiful white beard she immediately recognized the phantom. It was of course her father. Thus every time the patient merged into a love affair the picture of the father inopportunely appeared and prevented her from adjusting herself psychologically to her husband.

I purposely chose this case as an illustration because it is simple, obvious, and quite typical of many marriages which are crippled through the neurosis of the wife. The unhappiness always lies in a too firm attachment to the parents. The offspring remains in the infantile relations. We can find here one of the most important tasks of pedagogy, namely, the solution of the problem how to free the growing individual from his unconscious attachments to the influences of the infantile milieu, in such a manner that he may retain whatever there is in it that is suitable and reject whatever is unsuitable. To solve this difficult question on the part of the child seems to me impossible at present. We know as yet too little about the child’s emotional processes. The first and only real contribution to the literature on this subject has in fact appeared during the present year. It is the analysis of a five-year-old boy published by Freud.

The difficulties on the part of the child are very great. They should not, however, be so great on the part of the parents. In many ways the parents could manage more carefully and more indulgently the love of children. The sins committed against favorite children by the undue love of the parents could perhaps be avoided through a wider knowledge of the child’s mind. For many reasons I find it impossible to tell you anything of general validity concerning the bringing up of children as it is affected by this problem. We are as yet very far from general prescriptions and rules; are still in the realm of casuistry. Unfortunately our knowledge of the finer mental processes in the child is so meagre that we are after all not in any position to say where the greater trouble lies, whether in the parents, in the child, or in the conception of the milieu. Only psychanalyses of the kind that Professor Freud has published in our Jahrbuch, 1909, will help us out of this difficulty. Such comprehensive and profound observations should act as a strong inducement to all teachers to occupy themselves with Freud’s psychology. This psychology offers more for practical pedagogy than the physiological psychology of the present.