The Blue Book Magazine/La Belle Marquise

La Belle Marquise

Illustrated by

Paul Lehman

Paris—the Legion convention—and swift

action to defeat a daring criminal: one of

the most stirring stories even the author

of “The Pirate of Algiers” ever wrote.

“Grab her mitts, Alice,” I said; and I made a thorough job of that gag.

I HALTED my taxi across the street from Hollock's apartment, paid the driver, dodged through the line of vehicles ascending the hill, and was clear. Then the first bullet struck my hat and jerked it over my eyes.

The Rue de Maubeuge was fairly clear of down-bound traffic at the noon hour. I was expecting nothing, heard no shot—and yet I realized instantly what had happened. I made a quick leap forward, and it saved my life. The second bullet ripped my collar, just under my ear. Some one was shooting from behind and above, and I stopped to ask no questions about it. I broke all records, and dodged safely into Hollock's entry.

In two minutes I was up the stairs and in his apartment. Alice Vincent was ahead of me; she and Hollock stared at my unceremonious entry.

“Get busy, Holly!” I panted. “Upper window across the street—trifle with silencer—must be Tellier himself—”

I held a finger to my ripped collar. Hollock was out of his chair and at the telephone without a word more. Obviously, he had made all arrangements at the mairie of the quarter, for he merely gave his name and sketched what had happened. Then he hung up and turned.

“Tellier was probablylocated over there, waiting to get me,” he said quietly. “He saw you—and let loose. They'll not find him; he'll be out of Paris in half an hour.”

Alice said nothing, but sat staring at me, with horror in her eyes. I told her she'd better play safe and marry me at once, instead of waiting the six months she had exacted; but she did not rise to the lure. Even in Paris, where anything happens, bullets aren't common.

HOLLY gave me a cigarette and settled back in his chair, calmly enough. Seeing another chap missed by a bullet was nothing to worry an ace and general daredevil like Hollock. He held a French aviation commission, about all the medals that could be raked in, and the confidence of several governments. He passed a hand over his slightly bald front and grinned at me.

“Much obliged for springing the trap, Buddy Barnes!” he said. “We'd better keep away from the windows and leave it to the gendarmes. Lunch will be up in a minute—I've taught that corner restaurant to broil lobsters, American style. D'you know, Buddy, this has relieved me a whole lot!”

“It ought to,” I said sharply. “A new hat—and look at the holes in it! And then look at my coat-collar!”

“Any stoppeuse at any corner can fix that, and I'll buy you a new hat,” said Hollock carelessly. 'But this shows Tellier hasn't any idea that we know something of his plans for Saturday night, and the Marquise de Grammont. Savvy? Otherwise, he'd never have fixed up this little ambuscade. He's hated me since we mixed it up during the war, but you're the one who got me on his trail the other day—Alice assisting—and when he got a good crack at you he couldn't pass it up! So it blew the whole Works for him, and now he'll stay out of Paris for a while—and use his puppets and crooks to milk the Legionaries he can catch. Which will help us a lot.”

Alice turned her gaze to him. “Thanks for the us,” she said quietly.

“I mean me and Buddy,” said Hollock. She smiled.

“No. Us. I'm in this, and I mean to stay in. You're protecting the American Legion—”

Her tone was eloquent, and I glanced uncomfortably at Holly. He shrugged, frowningly. It was no game for a girl like Alice Vincent—fresh from home, knowing only school French, and engaged to be married in six months to Buddy Barnes, unless she changed her mind.

“Protection for the Legion in convention assembled!” I broke in ironically. “That sounds fine, that does! Alice Vincent, art student, Jim Barnes, lawyer, and Commandant Chauncey Levinfort Hollock, general utility man of the French aviation service—engaged in protecting the tender and unsophisticated boys of the American Legion! Id like to hear the laugh that line would get from some of those boys!”

“Well, it's true!” snapped Alice, getting rather red. “You know it is, too—you needn't try to make fun of it, either!”

IT was true, and that was why I didn't want her in the business. Largely by accident, Alice and I had put Hollock on the trail of the man he most wanted—one Jean Emile Tellier, former army officer and now a champion crook with plans all laid to soak as many of the American Legion convention as he could reach for their money—and worse. Much worse, in fact. All Paris marveled at the magnificent way the Legion men behaved themselves in the face of all manner of moral temptations; yet there are a few weak sisters or idle spendthrifts in every crowd. Tellier was after them, and he had them all spotted, too.

Hollock was after Tellier, and I was with him—and now Alice proclaimed herself in it too, in a tone of voice which showed us argument was silly. Hollock was, I felt sure, one of the men assigned by the government to watch over its large flock of guests, for France was taking no chances. Official figures showed three hundred thousand foreigners, all criminals, reds or potential criminals, on French soil—and she meant to protect the Legion so far as she could against all such. And against her own criminals as well.

We had caught Tellier red-handed and had missed him by a hair; he was a remarkable man, and knew his danger now. He did not know, however, that we had secured a slant at his plans and, victims and associates—enough to give us a working basis. And he was mixed in everything from straight robbery to dope and white slavery. It was no girl's game.

“If you want in, stay in,” said Holly, looking quietly at Alice. “You can help a lot. But you risk a hundred times as much as we do, remember!”

“I stay in,” she said, simply. “Remember on your own part that I'm twenty-two years old, have a brain and hands, and can look at the seamy side of life without a shiver. That's the epitome of modern education—for the younger generation.”

We both broke into a laugh, and just then a waiter came with luncheon, and we went into the dining-room as soon as he was ready to serve. Holly had done things up handsomely, with a 1906 Vouvray that would make your head bubble like its own greenish-yellow depths.

Before the waiter, we kept off the business for which we had assembled. Midway of the meal, Holly was summoned to the telephone. He spoke briefly, and returned with a shake of his head.

“The bird was gone, but they got his gun and found his nest and pinched a couple of hopheads—poor devils!” he said. “He probably knows now that they've got his description and photos; he's beating it out of Paris, perhaps out of France. No one knows better than he just how efficient this frog police system can be. Well, here's luck to our marquise!”

“And a new lid for me,” I added.

When the waiter had departed, the three of us settled down to discussion. It was Friday, and for two days we had been probing for light on the secret activities of Tellier and his precious confederates.

We knew that a certain Marquise de Grammont was giving a tea or reception for a number of the Legion convention on Saturday, at her Passy home. We knew there was no such person or title; the historic name had been borrowed, the title invented. Our first brush with Tellier had yielded five names, four American, and that of a certain Gabrielle at an address in Rue de l'Assomption—a street dividing Passy from Auteuil. That this Gabrielle was the false Marquise de Grammont, was fairly certain.

“Gabrielle Fontaine,” said Hollock, “is a minor lyric artiste who lives between Paris and Nice, and who works anyone worth working. This covers her case, briefly—the details are not appetizing. The house in question is a very fine one; it's been rented for three months, unfurnished, to a man who answers the description of Tellier. This rental cost him fifteen thousand francs; another five thousand for expenses, say, and we have an expenditure of twenty thousand. For what? One evening's work. How does he expect to make a killing of size in one evening?”

Exactly the thing I wanted—a pair of

real pistols. They came high, but I

did not argue over the price.

“We don't know it's for only one evening,” I objected.

“Neither Tellier nor Gabrielle could keep up such a bluff in Paris,” said Holly. “This is a quick, bold play for big stakes. Have either of you learned anything about the four American names?”

I shook my head. “Larned, who gave him the other three names and who seems to be one of his men, remains a mystery. He isn't a delegate to the convention, anyhow. I couldn't get any track of Wilberforce or of Humphry, but I may learn something later from the convention headquarters. Severance is a delegate from a Michigan post. He's stopping at the Continental, therefore has money.”

“He has,” put in Alice. We turned to her.

“You know him?” asked Hollock.

“We're from the same town, near Detroit.” Alice smiled, enjoying our surprise. “Of course I know Frank Severance!” she added. “He has more money than sense, or had; he inherited the one without the other. Since the war he's done little but spend money—it means nothing to him.”

“Just the sort Tellier would pick on,” commented Hollock. “Question is, whether this party is being staged for his sole benefit or whether others are in on it?”

“Deduce,” I said, with a shrug. “A man of that stamp would have friends of the same type. Personally, I'm not interested in saving fools from the result of their folly—if he's bringing other birds into Tellier's net, I'd let 'em go! But we're out to fight Tellier, so—”

“Exactly,” and Holly grinned, his gray eyes twinkling at me. “Nothing on with the convention until its formal opening next week, is there? Then our man is probably enjoying life, with all the trimmings. Buddy, you're deputed to go around and see if you can warn him off the Marquise de Grammont and her staged party.”

I LOOKED at my watch and settled back.

“All right. Alice and I will saunter around there at tea-time. Are we going to that party, if it's pulled off?”

“You bet we are,” said Hollock. “Well manage it easily enough, for I've the lay of the house in my head. Tellier has probably warned his crowd against us, but hasn't had any chance to point us out; a change of names ought to protect us.”

“What about more bullets from windows?” asked Alice anxiously. Holly grinned again.

“No danger. Tellier himself was the only one with nerve and hatred enough to pull that sort of stuff! He's gone, and it wont be, repeated. He had to make a desperate play to get rid of me or Buddy, since we knew him and were blocking his game. He lost, and you can gamble he's outside of Paris and still going, right now—he'll direct operations from a safe distance. Well, that wont help him! We'll get things cleaned up here, and go after him.”

“About the warning—no good being explicit?” I asked.

“Not a bit. Size up your man and use your head. Suppose we meet for lunch tomorrow at that brasserie in the Rue Jean Jacques Rousseau, behind the Louvre, and report progress.”

So agreed, we parted, Alice going with me. We walked, having plenty of time, and Alice enjoyed window-shopping in the many antique shops of the quarter. I was keeping my eye open' for a weapon-shop—the French run to all variety of fancy firearms and other things, and I wanted a pistol badly. My eyes were open to what we were now up against.

I had known, naturally, that it was a question of hotel rats, white slavers, and dope handlers, to put the case baldly, but had not previously appreciated their readiness to hit back—and to hit first if they could. When it came to this, Jim Barnes meant to be on the spot himself. So, when I saw exactly the thing I wanted in the window of an antique shop, we went in and Alice looked on wonderingly while I bought it.

Not a pistol, but a pair of them—real pistols, beautiful old silver-mounted weapons. Each was barely three inches long. They were in a case, complete with some caps, loaders and bullet-mold and powder-flask. They came high, but I did not argue over the price.

“And will you please tell me why?” demanded Alice, when we were walking on toward the Continental. “I'd think those things more dangerous to the man who shot them, than to—”

“Maybe,” I admitted. “But if you notice, they take a bullet the size of a 30-30, and are only good for short distances, and would go into a waistcoat pocket. No. sense lugging around an automatic! If I need one bullet, I need it bad and quick—and I'll wager these little toys will do the business beautifully. Anyhow, they suit me.”

Alice had to be content with that.

WE reached our destination a bit ahead of tea-time, and lucky we did. We had no sooner come into the big rectangular lounge facing the court, than up jumped a man ahead of us and came at Alice with beaming face and hand extended.

“Alice Vincent—of all people! How are you? What you doing here?” .

“Looking for tea—how are you, Frank? Mr. Severance, Mr. Pendleton.”

Severance gave me a hearty grip and then turned to Alice again. I sized him up easily—he was the back-slapping type, vain as a peacock, fairly good looking, expensively dressed, and was probably very popular at home. He had a loud voice, which he used, and he evidently liked to shine.

“Come along and meet a friend of mine,' he said warmly. “Old French nobility—ah, here we are! Marquise de Grammont, let me present Miss Vincent, from my old home town—and Mr. Pendleton.”

I hoped nobody would recognize me as Buddy Barnes—that voice of his carried.

We joined them, and Severance ordered tea. The fake marquise was a smooth article, no doubt of that; she was good-looking in a cattish French way, was dressed to kill, and spoke English with a pronounced “z”? accent, more like an Italian than a Frenchwoman. She almost ignored me, and devoted herself to Alice.

“Convention? Sure!” Severance leaned back, took a cigarette from a jeweled case, and looked the lord of creation. “Were showing 'em how we do things, what? Seen the wreath we brought over for the Unknown Soldier's tomb? It's a peach—nothing like it ever seen over here!”

“You were here during the war?” I asked.

“Me? No such luck,” he said, and deflated a little. “Training camp. Listen, I'm to be the guest of honor at some doings tomorrow at the Marquise's chateau—you and Miss Vincent look in, will you? Here's a couple of cards—”

HE handed me two ornately embossed cards, decorated with a huge coat of arms, for the tea. I wondered how the man could be so taken in, with talk of a chateau in Paris, and this horrible lack of all taste—but just then the Marquise seconded the invitation.

“You mus' come!” she said, using her eyes, and then took Alice's hand. “Will you help me serve ze tea, if you please? It will be so kind, my dear! So many people are out of town for ze holidays, and my famille, zey spik ze Anglais so poor—”

I had a good slant on this, too. The faker! She would not dare drag in any resident American women, who would all know there was no Marquise de Grammont; but with Alice to assist, she could make a grand impression on Severance and his friends. It was a lovely game.

I pocketed the cards and winked at Alice, and she assented very sweetly. Then she said something to the Marquise which I didn't catch, but which had swift results. Next thing I knew, Severance was giving his attention to Alice, and the Marquise was using all her eyes on me. And, man, how she could use them! How she could talk of the nobility she knew! How she could act! With all I knew about her, and the plenty I could guess, she half fooled me into thinking she might be all right after all. We were old friends in five minutes, and intimate in ten. When she hinted that she might show me around a bit, I took her right up on it—if she wanted to play me for a sucker, she could!

So we all had a grand time. Alice agreed to show up and help the Marquise next day, and I said I might bring a friend with me, and everything was lovely. Severance was tickled to show off his friends among the nobility; you can gamble he lost no opportunities, either!

“What did you say to the painted lady that made her so keen for me?” I asked Alice, when we were on our way elsewhere. She squeezed my hand under her arm, and laughed delightedly.

“I told her you had been divorced three times and still had five million dollars in the bank—and that I hoped to marry you. At least, I didn't have to tell her this last. She saw it. And now she's on your trail. What you going to do about it, Buddy?”

“Whew!” I said. “That whole gang will be on my trail now! Good for you—I bet well have some fun tomorrow afternoon and evening!”

We had a good deal more than any of us bargained for.

We arranged with Holly that he and I were to go to the tea as mere guests, under the names of Pendleton and Howard. Alice would go on her own, and be there when we arrived—and find out whatever she could about the outfit.

“There's one risk, of course,” said Holly thoughtfully, as we talked it over at luncheon Saturday. “Tellier's gang may be wise to us, and the Marquise may be setting a trap.”

“Possible but not likely,” I said, “to judge from the way she fell for the stuff Alice told her about me. I think she's on the level. When does the show start tonight?”

“At six,” said Alice. “Or a little after.”

“Then we'll have to dress. I'd sure like to know what they aim to pull off in two hours' time! Will you come around for me, Holly?”

He nodded. Alice and I went off to see a film that would never be shown in America, and we had an enjoyable time.

Hollock showed up promptly at five-forty. I was waiting in the lobby, and came out to his taxi. I had spent some little time finding out how to work those baby pistols of mine, and now had one in each pocket of my smoking jacket, capped and ready; but did not mention the fact to Holly. He had his straight-handled ebony stick.

“That'll give you no help,” I said. “You'll have to turn it in with your hat.”

“I'll know where it is,” he grunted. “No more news?”

“None. You?”

He shook his head, and we rode out along the quay in silence, until we turned off at the Grenelle bridge for the Rue de l'Assomption. Five minutes later, we had arrived.

The house was a massive square building of stone, set behind a high iron fence among gardens. Across the narrow street were the tall brick wall and large grounds of a private school; on either side were other residences in extensive grounds, and the lots were so deep that trees hid the buildings in the rear.

“Now we'll find,” said Holly, as we were admitted by the gate porter and walked on toward the house, “why our friends rented an unfurnished place—”

“Because they wanted to furnish it,” I laughed. He nodded gravely.

“Exactly; for their own ends. Also, why they picked such a situation. Anything could happen in that house, from a yell to a gunshot, and it wouldn't be heard in the street unless some one were listening.”

“Oh!” I said. “You'll have some one there listening?”

He only grinned at me.

WE were among the first to arrive, which was what we wanted. Our cards had to be shown, then a liveried servant took us upstairs. We had a glimpse of vast glittering rooms, gay with flowers and brocaded hangings, and caught the strains of an orchestra.

“For a one-night stand,” muttered Holly in my ear, “it's well staged!”

When we came down, I was impressed, despite my knowledge, by the gaudy trap. How many of the crowd were in the secret, it was impossible to say—perhaps only a few of them knew anything definite. It was a well-dressed assemblage, and some of the women were magnificently gowned. We stood for a moment, gazing around, then Holly touched my arm.

“See that. woman with the diamond necklace? A*real countess, but a dope-fiend. The man under that chandelier, with the distinguished whiskers, is Baron Gatz—expelled from the Legion of Honor last year for things not talked about. Watch your step, Buddy! Come on.”

We made our way to the Marquise and Alice, who were surrounded by a little throng.

Alice was in beaded white, the Marquise in bright flaming scarlet—an apt choice of colors, I thought. I presented my friend Howard as a business associate and left him to keep the rouged and painted lady entertained while I greeted Alice. “Any news?” I asked.

“Suspicion only—the room behind the winter garden. Not sure—”

Almost at once, I found myself taken in hand by the Marquise, who evidently meant to play me for all I was worth before Severance arrived. She did it, too, and if I met her halfway it was her own fault. This, too, let Hollock efface himself—he was too well known to take chances under an assumed name. I met all the nobility, real and assumed, on the place and then slid the Marquise out of the throng and off to the winter garden for a quiet chat.

She was a swift worker, and I played up to her in good shape. The winter garden was a semi-circular room under glass, filled with exotic plants. It was flung open to the warm summer evening, and a door went out of it to one side. I wanted to have a look at what was behind that door, but kept my desire to myself. Since she had money in mind, I talked carelessly of large sums, and presently she asked if I ever gambled.

“Never,” I said, “unless I get a good chance—”

JUST then we were interrupted by a thin, pallid man with some sort of borrowed title, who appeared and made the lady a sign. I knew Severance had arrived, by the suave manner in which the Marquise disengaged herself. I took her back to the crowd, then lost myself and slipped into the winter garden again and went to that door. It was unlocked, and one quick glance was enough. I went back and circulated in the precious gang. Severance and two other men had arrived, both of his own type, and after meeting them I drifted around and found Hollock in a corner by himself.

“Zey have all forgot' me,” said the Marquise, “S'all we go away and have ze little chat togezzer, yes? Upstairs?”

“Any luck?” he asked.

I nodded. “Gambling lay-out in the back room. Looked like roulette. I thought it was illegal in France?”

He only shrugged, his gray eyes roving about the place.

“More in it than mere gambling, Buddy—somewhere! May be anything from plain robbery to the badger game. Most of this gang are here merely to form a background; probably half a dozen in all will be on the inside. Spotted any of 'em?”

I pointed out the thin, pallid man who had summoned the Marquise. Holly smiled. “His real name's Frontin. Former croupier at Monte Carlo, and a bad egg. Hm! And Baron Gatz! I fancy this affair will be pulled off without the Marquise. She'll try to keep you out of it, Buddy—they're after Severance and his pals tonight, savvy?. They'll pluck you another time.”

We separated, and I soon found the Marquise keeping me and Severance both on her string. He was loud-voiced and aggressive and sure of himself as ever. We all moved into a huge dining-room, where a gorgeous supper was served, with plenty of wine and liquor. I noticed that Baron Gatz made quite a hit with Severance, and stuck close to us. Severance had too much to drink, and presently leaned over to the Marquise.

“When does that little game start, Marquise?”

“Whenever you like,” and she laughed trillingly. “You want to play, eh? Come, well all go in. Tell your friends—but nobody else. It is not for all ze world, zis game!” She looked up at me, and pressed my hand. “You like it, ze roulette? Zen you shall come, and your friend too—”

I saw Hollock talking with Alice Vincent, a startled look on his face. She had discovered something, then! No time to talk, though; a gentle dispersal was accomplished, most of the crowd remaining and a few drifting off to the room behind the winter garden. The Marquise kept me and Severance with her. Alice did not come.

Yet she had somehow dropped on the secret—I saw it by the look in Holly's eye, by the quick grin he flashed me, by his signal to go slow and wait. He knew how what was coming. At least, he thought he did. None of us guessed the dark and bitter work ahead.

THIS gambling-room held two roulette tables, and was of fair size. Two of the long windows were open, giving upon the garden. 'Severance and his two friends made the room loud with boisterous talk. I was there, Holly, Baron Gatz, Frontin and half a dozen others, two of them women. One of these women, amid much laughter, got behind one of the tables as croupier, while Frontin was assigned to the other by the Marquise. There were no chips, all playing being with money. The Marquise, frankly the house, furnished each croupier with a bale of hundred-franc notes and another of thousands. Then, amid keen excitement, the ball was opened.

Almost at once, I found the Marquise on my arm.

“You do not play, M'sieur Pendleton?” she asked. I shook my head.

“Not yet—wait a bit. I've forgotten roulette, amd must have another drink or so to get warmed up.”

She laughed, and squeezed my arm. Severance and his two friends were at Frontin's table. Forgetful of all else, each of them holding a sheaf of notes, they were laying down bets.

“Zey have all forgot' me,” said the Marquise, and gave me a sidelong glance. “Gall we go away and have ze little chat togezzer, yes? Upstairs?”

“She'll try to keep you out of it, Buddy!” The prophetic words of Hollock drifted back to me, and catching his eye, I got one ironic look. I assented to the lady's question eagerly.

“You mean it? I'd like nothing better! Come on—can't we slip upstairs without going through the whole crowd?”

She nodded. “I'll show you!”

And she did. We slipped quietly upstairs by a back way.

NOW I could guess whatever was going to be pulled off down there in that “back room, would come before long; otherwise, she'd not have tried to get me out of it. Also, she may have wanted a good alibi. So I knew exactly what I meant to do, guessing that no more of the upstairs had been furnished for the occasion than was absolutely necessary.

However, the thing was sprung on me, for in the upstairs hall we ran into Alice—and I don't know which of us was the more astonished. She was carrying her velvet cloak, and I knew Hollock must have told her to get out and away at once.

“You are not leaving?” exclaimed the Marquise, with a nasty intonation.

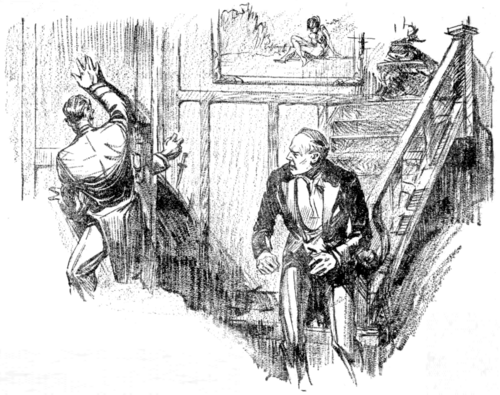

I had two handkerchiefs, fortunately; I jerked them out, rolled up one in a ball, drew the other over it, and had an excellent gag. I was just behind the Marquise.

“Grab her mitts, Alice,” I said. By the time this slang phrase percolated to the painted lady's brain, she was too late.

I whipped the improvised gag over her head and drew it around and knotted it under her slicked hair; Alice had her by both slim wrists. Fortunately, I made a merciless, thorough job of that gag. How the cat fought! Not until I reached down, caught her ankles, and dumped her over on the floor did we really get her under control. Even then she wriggled about like a snake, until I yanked up my trouser-legs and got my garters off.

A garter makes an excellent thing to tie up wrists or ankles with, if handled right. In two minutes we had the Marquise bound and gagged, helpless. I straightened up and looked at Alice, who was panting, starry-eyed, flushed.

“Get out, quick!” I said.

She nodded and disappeared.

All this time we were in the upper hall, and not a soul was in sight. On our right were the rooms, open and lighted, used to receive the hats and cloaks of the visitors. All the doors on the other side were closed. I stepped to the first, found it open, and went into a bare, musty, closed room. Slipping back, I picked up the Marquise.

“Be a good girl, now, Gabrielle, and you wont get hurt,” I said. She stiffened in my arms at this use of her real name, her eyes staring wildly at me. I carried her into the room, put her down on the floor, came out and closed the door. Then I went back to the roulette room, as I had come, but faster.

And I was barely in time—for the tragedy, as I thought then. In reality, for the prelude of what was to be the, real drama.

I slammed the door shut on the wrist of a hand that gripped a knife.

I OPENED the door and slipped into the room, in a dead hush. Severance was facing Baron Gatz and his splendid whiskers, in a furious altercation. Even as I softly shut the door, Gatz lightly struck Severance across the face with his white gloves. In reply, Severance hit him a heavy crack on the chin—not knowing he was merely being fixed for a duel. The baron went over backward, rolled, and lay with his head under the roulette table.

There was instant confusion. Frontin, with suspicious presence of mind—I saw smiling to himself—leaned over the recumbent baron, then pulled him out. His face was more ghastly than ever as he rose.

“Dead!” he croaked. “Struck his head—where is Docteur Benet?”

The confusion died into stricken silence. The doctor, most opportunely among the guests, shoved forward and leaned over the baron. After a moment he, too, rose. “Dead,” he said, and threw out his hands helplessly.

The scheme was evident enough now. Severance and his two friends, their piles of banknotes forgotten, stood staring. They were sobered and horrified.

I came quietly to Hollock's side.

“Wait,” he said in my ear. “Wait. Alice saw the gendarmes ready. Let 'em spring it.”

Frontin stepped out. Now he was speaking in perfect English, as he held up a hand.

“Ladies, please retire!” he said. “And breathe not a word of this. We must protect our American guests. Remember, it was an accident—everyone else, kindly remain as you are!”

The two or three women slipped out of the room. There remained Severance, his two pals, and half a dozen men. Hollock pulled me back by a window, where the low lights above the tables left us unobserved. All were watching Severance, who had lost his confident air and was staring around, gulping.

It was well staged. The women who had departed gave the signal, of course. A door opened, and two gendarmes stepped into the room.

“Keep your places, gentlemen,” said one of them—in English. I glanced at Hollock, but he shook his head, and quietly stepped out the open window to the balcony above the garden. I was with him at once, unseen, and we watched out the drama. What was now said, was spoken in English—for the benefit of Severance and his friends, naturally, They were far too excited, too utterly appalled, to be conscious of the incongruity.

“What is this?” said one of the gendarmes. “Roulette? This is against the law—ah! A man hurt—why, it is Baron Gatz! Quick, comrade!”

For a third time, a man knelt above the baron's whiskers, and rose with the one reiterated word: “Dead!”

Out came pistols, and with them, notebooks. The gendarmes looked at Severance. “You did this, monsieur? You are under arrest—”

Poor Severance, all this while, had said mot a word, but his face grew whiter and whiter. “An accident—didn't mean to do it—” he blurted desperately.

“Monsieur,” broke in the gendarme, “you are engaged here in roulette, against the law of France. You have killed a man. These witnesses will tell their story; the fact remains, a man is dead! Further, no ordinary man, but one prominent, well-born, noble—Baron Gatz! Let there be no talk of accidents. The newspapers will not believe such a tale.”

Sweat began to streak the face of Severance. Frontin had his cue, however, and now came forward, giving his assumed name—the Vicomte something or other.

“Not so fast, I beg of you!” he said to the gendarmes. “We, all of us, saw what took place; an altercation, Baron Gatz slapped this gentleman's face, and Mr. Severance hit him. He fell, struck his head—and you see the result—”

“Worse and worse!” snapped the gendarme. “Then you admit he was killed as the result of a blow? Who is this murderer—a foreigner?”

“He is one of the American Legion, a friend of France!” cried Frontin dramatically. “We cannot allow this accident to be called a murder! Our friend, our guest—here, monsieur, let me speak with you in private.”

He took the gendarme to one side, whispered. The gendarme threw up his arms.

“Impossible!” he cried out loudly. “To hush this up—impossible! It would mean the loss of my position—and consider my comrade yonder! Besides, a man of the quality of Baron Gatz—no, no! Do not mention such a thing—”

“But there are ways!” said Frontin hastily. “You know it could be done—”

Severance stepped toward them.

“I—let me speak a word,” he said huskily. “It was an accident, yes—I didn't mean to do it—if there's any way it can be kept quiet, I'll pay well—”

“Impossible, monsieur,” said the gendarme sternly.

I TOUCHED Hollock's arm and looked at him, but he shook his head and stepped farther back. The farce went on—it was sheer farce, for the moment, and everybody except Severance and his friends enjoyed themselves. To cut a long matter short, a sum was agreed upon and it was no small sum; we could not catch the amount, but could see Severance and his two friends making up the money and it seemed to clean them out of American and French notes. He passed it to Frontin, who drew them aside, toward our window.

“Slip out and go now, quickly,” said Frontin. “Leave me to settle with these gendarmes. We'll arrange everything. We must keep it out of the papers if possible—”

Then the gendarmes intervened. They had changed their minds; they could not sell their honor! Severance yanked out a folded book of bankers' checks.

“One thousand dollars more—yes or no?” he demanded, breathing heavily.

Then he was signing the checks and turning them over. Frontin had not expected this, I could see, and was delighted. He winked at the gendarmes, and into their hands put the big pile of bills.

“I'll see these gentlemen out, and then come back to arrange with you,” he said, and jerked his head at Severance. He wanted to get rid of the three dupes at once, before anything could go wrong. He did it very neatly, too—got them out, and went with them.

As soon as the door closed, Baron Gatz got up and grinned, and everybody shook ` hands. Besides the two imitation gendarmes, there were the baron, with the doctor, and four others. Eight in all, as I figured up afterward.

“All right, Buddy,” said Hollock, and we walked in on the party.

“SUPPOSE we speak French for a change, monsieurs,” said Hollock, with calm assurance.

His command of the language is fluent; but he had previously denied all knowledge of it. The gang stared at us, unspeakably startled by this fact, and by our appearance. Holly smiled at them and lighted a cigarette—so they could see the police whistle in his fingers. In fact, he had all the air of a high-class French police official, and in his buttonhole had mysteriously appeared his Legion of Honor rosette. They did not miss it, either. `

“So you belong to the prefecture of this arrondissement?” he said to the two fake gendarmes. “The inspector, I believe, is waiting outside. He'll be most interested to meet you, gentlemen. And you, my dear Baron, with your load of wealth.”

The money had all gravitated to Baron Gatz, together with that left on the tables.

“Sacred name of a black dog!” gasped somebody. “He is of the police! Not an American!”

“What charming discernment!” said Holly genially. “Our little Frontin gave the game away, yes. He's very useful to us, this Frontin. Not very wise of Tellier to trust him, eh? But Gabrielle is caught, and you, gentlemen, are caught also.”

The use of those names fairly stunned them all. Not one of them doubted that Holly was actually from the prefecture. The baron trembled in his shoes as Holly held out a hand to him.

“Come, the money! Thank you. And now, those pistols—”

The baron mechanically handed over the wad of bills, which Hollock stuffed into his pockets. The gendarmes, however, drew back, scowling.

“Did that dog of a Frontin blow the game?” one of them demanded.

“He did, naturally,” said Holly.

Up to then, they were all completely cowed, and given another three minutes, we would have won the whole pot hands down. A police official in France commands a peculiar respect and fear, even from criminals, which is not given to agents or even gendarmes; for behind him is the deadly weight of the law. And French law is not like American law—it is justice, swift and sure and deadly in the extreme. It is even more deadly than British justice, for it is bound in red tape which is pitiless and terrible.

So, left alone, none of these eight men would have resisted the two of us, for their passions were paralyzed. But, at this instant, the door opened and Frontin stepped into the room without seeing us.

I think he never did see us. It was as though a flame leaped through the group of men who thought he had betrayed them all. A low growl broke from them; two of them whirled, caught him, dragged him down, and I saw the flash of a knife. Frontin flung them off and came to his feet, blood on his shirt-front—then one of the gendarmes shot him between the eyes.

The other gendarme flung himself on Hollock, brandishing his pistol, and the crowd came for us. The spell was broken.

THAT second gendarme was too melodramatic for his own good, because as he leveled his pistol, my deadly little toy spurted fire into him and he went down. The other pistol caught in my pocket, and the gang were all over us in an instant.

For a moment or two it was a grand and glorious free-for-all. Fortunately, evening dress does not lend itself to hidden weapons. Two or three of the crowd had knives, but got little chance to use them; I remember sending home a straight right to the chin of Baron Gatz, but his beautiful whiskers were like a padded protector, and it only bounced him across the room. Another came in his place, steel blade darting at me; we were back to back now, Holly and I, as they crowded us, rammed us, surrounded and tore at us, bore us back by sheer weight.

Only two movie heroes can beat down seven men with any ease. When a mad rush sent us reeling against the wall, I gripped at the door there and flung it open—it was the door leading upstairs, the way the Marquise had shown me. Hollock fell through it, and I came after him, then slammed the door shut—on the wrist of a hand that gripped a knife. The knife fell, I opened the door slightly, and slammed it again as the hand vanished. A rush of bodies sent it quivering.

“Up!” I panted, catching Holly to his feet. Somebody had reached him under the belt; he was groaning and gasping for breath. “Blasted police—too slow—”

The stairs were dark—a door at the top, French fashion, was closed. We were halfway up when the door at the bottom smashed open and figures came leaping. There was a shot, and the bullet whined and thudded between us. They had recollected the pistols of the fake gendarmes.

I had one shot left, and used it. In vain! At the same instant, the door above us opened, I heard the Marquise shrieking something, saw her and several men behind her coming down at us. She had slipped the gag, or had been discovered—and we were caught past escape.

Again the pistol roared below us. A frightful scream broke from the woman above, and she pitched forward, falling headlong down the stairs—the bullet, meant for us, had hit her. She struck me and Holly together, swept us off our feet, and the three of us plunged slap into the mounting men behind us. Something knocked the wind out of me, and as I went to sleep I heard the shrill vibration of a police whistle......

I never saw a more terrible change in a man than in Severance, when Hollock and I walked into his hotel room, unannounced, the next morning. He leaped up, staring at us, eyes bloodshot, face unshaven and haggard. He had not slept that night.

“You—ah, you were there!” he bleated. “You know about it?”

Hollock opened the package in his hand and spread out the money on the table.

“There's your money, Severance,” he said. “Divide it among the three of you as it was given. And you'd better go back to America.”

Severance stared from us to the money.

“What d'you mean?” he stammered. “How'd you get this? The baron—”

“The baron's in jail,” said Holly. “It was all a faked scheme to make you pay up, you poor fool! Well, you've paid for it—”

“Faked? Impossible!” cried Severance. “The Marquise—”

“There is no marquise,” said Holly sternly. “She was a cheap actress and worse, playing the part. Poor creature!”

Severance fumbled at the money, then drew back his hand sharply.

“Blood on it!” he exclaimed.

“Yes—her blood,” said Holly, not sparing him a jot. “She's dead. She's paid, and I guess you've paid a bit too. It was all a trap for fools. You and your pals were the fools.”

Severance dropped into a chair, as comprehension beat in on his brain.

“And you—you—what did you have to do with it?” he faltered. “Americans—”

“Americans, yes—that's why. You wouldn't understand.”

But the man did understand, and a shiver took him. Then he reached out, with a better gesture than I had thought was in him.

“Take it,” he said, shoving the money at us. “Take it. See that she—that she's buried properly—”

We left him sitting there with his head in his hands.

“Three Black Sheep” is the title of the next incident in this stirring series In the forthcoming February issue.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1949, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 75 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse