The British Warblers A History with Problems of Their Lives/Chiff-chaff

CHIFF CHAFF.

ADULT MALE

12

CHIFF-CHAFF.

Croatian, Vrbikova Zenika; Czechisch, Budnicek mensi; Danish, Gransanger; Dutch, Tzif-tzaf; Finnish, Kilttakertu; French, Bec-fin véloge; German, Weiden-Laubvogel; Hungarian, Vörhenyes rendike; Italian, Lui piccolo; Norwegian, Gransanger; Polish, Gajowka rudawa; Russian, Penotschka tentowka; Spanish, Mosquilla; Portuguese, Papa amoras.

DESCRIPTION OF THE PLUMAGE.

Adult Male in Spring.—Upper parts are bullish olive, slightly brighter on the rump. Upper tail-coverts bullish olive, similar to the crown and back. There is a distinct, though not conspicuous, superciliary stripe, and the lores are slightly dusky. The ear-coverts and the side of the neck are bullish olive, slightly lighter than the back. Upper parts of the wings and tail are brownish grey, shafts of the tail-feathers light purplish brown, the outer edges being margined with buffish olive. The shafts of the wing-feathers are dark purplish brown, the outer half of the innermost secondaries greyish brown and edged with buffish olive. The tips of the primaries are rather darker brown, the greater coverts greyish brown narrowly edged with buffish olive, and the medium and smaller coverts broadly edged with the same colour, almost hiding the brownish grey ground colour. The throat is whitish with a narrow inconspicuous line of sulphur yellow, and is also margined with a similar line and a broader line of light smoky ash colour, which latter colour extends to the crop, sides of the breasts, and flanks.

The abdomen is ashy white, becoming almost white towards the crissum; the feathers on the crop and abdomen have a dull sulphur coloured pattern on each side, which, when the feathers are in perfect order, form narrow longitudinal stripes. The under tail-coverts are whitish sulphur yellow, and the under surface of the tail and wings light greyish brown with white shafts. Axillaries and under wing-coverts are sulphur yellow. The iris is dark brown and the minute feathers on the eyelid whitish. Upper mandible dark purplish brown, lower mandible the same colour at the tip, but fleshy brown towards the base. Feet are blackish brown.

The sexes are alike in colour, but the female is somewhat smaller.

Male in Autumn.—The upper parts are olive brown, slightly lighter and more yellow on the rump. The small feathers on the eyelid are whitish yellow, and the superciliary stripe light buff, with a tinge of yellow just over the eye. The sides of the head are olive buff with an indistinct light centre to each feather. The upper parts of the tail and the wings are greyish brown, edged with olive green. The largest feather of the bastard wing is uniform dark greyish brown, the innermost secondaries have broad olive green edges to the feathers. The under parts are whitish, the throat, neck, chest, and flanks being suffused with a rich warm buff, rather

CHIFF CHAFF.

ADULT FEMALE AND IMMATURE

pale on the throat, but rich on the flanks, with well-defined longitudinal stripes of sulphur yellow. The belly is pure white. The under tail-coverts are rich yellowish buff at the roots, but lighter and more yellow towards the tips. The under surface of the tail is lavender grey with white shafts to the feathers, and the under parts of the wings the same colour, but with light ashy grey margins to each feather. The under wing-coverts and the axillaries are rich sulphur yellow. The iris is dark brown and the lores grey, darkest near the eye. The bill is horn brown with the edges of both mandibles and the base of the lower brownish flesh. The gape and corner of the mouth are light orange buff. The tibia is olive yellow; legs, tarsus, and toes brownish grey, and soles olive green.

Fledglings.—The upper parts are dull grey, slightly brighter and more olive on the rump and upper tail-coverts. The wings and tail are brownish grey, the feathers being edged with olive yellow, and the edges on the least wing-coverts almost hide the brownish grey ground colour. The lores are smoky grey, and the superciliary stripe light olive yellow. The small feathers round the eye are whitish yellow. The sides of the head are dusky olive with light centres to each feather. The throat is whitish washed faintly with olive yellow, chest dull olive grey, and the flanks and abdomen white. The under tail-coverts are yellowish buff, and the under parts of the tail and wings greyish with whitish shafts; the under wing-coverts are sulphur yellow. The largest feather of the bastard wing is dark brownish grey. The iris is dark hazel. The bill is horn colour, the posterior edge of the upper and the base of the lower mandible being yellowish buff. The gape is light orange buff; tibia is yellowish white, tarsus and toes olive grey, and the soles olive yellow.

Nestling.—The plumage is much the same as the fledgling, but all the under parts are considerably lighter and more distinctly washed with yellow. The abdomen is more inclined to be whitish, and the superciliary stripe light yellowish buff.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION.

Over the greater part of England and Wales it is commonly distributed, but in certain parts of Norfolk, Suffolk, Cheshire, Lancashire, Cumberland, Cardigan, Merioneth, and Carnarvon it is either scarce or somewhat local.

As a breeding species it is nowhere plentiful in Scotland. It occurs, however, in some numbers on the east side south of the Firth of Forth, but north of this it becomes rare, although it has been seen on migration in Caithness and the Orkney and Shetland Islands. From the Isle of Skye there is only one record, but individuals seem to visit the western isles, especially Harris, more frequently.

To Ireland it is a common summer visitor, and it is not uncommon in the Channel Islands.

It is found throughout the greater part of Europe. Commencing with, its most south-westerly breeding point, we find it very numerous in Portugal, and plentiful during migration in Spain, but very scarce in the breeding season.

In the provinces of Hautes Pyrenees and Pyrenees Orientales it is scarce, only being found occasionally as a breeding species. In some of the more western provinces of France, such as Morbihan and Manche, it is not very numerous, but throughout the remainder of the country common, especially in the Province of Savoie.

To Belgium and the Netherlands it is a common summer visitor. Continuing northwards, we find it abundant on migration in Heligoland, and not uncommon during the same period in Denmark. In the south-east part of Jutland it has been found breeding. In Norway and Sweden it re-appears as a breeding species, reaching, in Norway, as far north as Bodo and Saltdalen. On the western side generally of Norway it is not common, but increases in numbers round Trondhiem. In the southern part of Sweden it is only seen on migration, but in the central and western parts it is common.

Returning to Central Europe, we find it a common breeding species over the greater part of Germany, but rare in Schleswig.

In Switzerland it seems to be common both in the plains and mountainous districts, even breeding in the Alpine valleys; and the same may be said of Italy, where it especially favours the olive groves in Tuscany and Liguria. In Sardinia it is common amongst the hills, and it also breeds in Sicily.

It does not remain in Greece during the summer months, and only passes through Turkey and Bulgaria on migration, but in Montenegro occurs as a breeding species.

Over the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy it is generally distributed, although somewhat rarely in Bohemia.

In Poland it is a common breeding species, neither is it rare in the Baltic Provinces, where it seems to prefer the more mountainous districts. The northern limit in Finland is a line drawn from the northern point of the Baltic to the western point of the Bay of Kandalak. In the southern parts it is rather rare, but more common in the central and northern districts. It breeds in great numbers round Pudasiarvi and the Lakes of Kiando and Hyrynsalmi, and is not rare near Sotkamo. In the vicinity of Kuopio and in parts of the Province of Abo it is common. It occurs near Helsingfors, Willmanstrand, and on the island of Kexholm on migration, and is a breeding species in the Province of Nyland. North of Lake Ladoga it is common, and it is also found in the environs of Onega, on the River Onega, and near the Lakes of Onega, Sego, and Wygo. It has occurred near Archangel, also in the province of Vologda, and we can trace it to the valley of the Petchora as far east as the Province of Perm.

In the Provinces of Pskov, St. Petersburg, Novgorod, Tver, Jaroslav and Moscow it is common. In the Province of Tula it only occurs on migration, but in those provinces lying between the Rivers Oka and Volga both on migration and as a breeding species. In the Province of Riazan it is found on the autumn migration only. In the valley of the Volga it is very numerous, also in the vicinity of the River Kama and its tributaries. It also occurs in the Provinces of Kasan, Viatka, Simbirsk, Samara, the northern parts of Orenburg, and we lose sight of it in the Ural Mountains and the Kirghiz Steppes. On migration it passes through Astrakan, Worometz, Orel, Tchernigov and Kiev. On the River Dnieper it is rare, but it occurs near Odessa and on the Crimea. On the northern slopes of the Caucasus it is not uncommon, but in Trans-Caucasia it is apparently a rare visitor, specimens having been obtained near Tiflis. On the autumn migration it has been found on the Eiver Amu Daria and as far east as Gilgit.

Its winter range is an extensive one. We find it common in Somaliland and Abyssinia, rare on the White Nile, but again common in Nubia, Egypt, Tunis, Algeria and Morocco. In Spain it is numerous, also in parts of the Pyrenees and the Province of Savoie, and individuals sometimes remain as far north as Normandy. A few are resident in Switzerland, but only in the neighbourhood of Geneva and in some of the more western parts. In Italy it is very common, more particularly in the south, and it also visits Corsica. In Greece and Corfu it is very plentiful, especially among the mountains in Attica, and we can trace it as far east as the south-western parts of Persia.

LIFE-HISTORY.

This bird is probably the best known of all the Warblers that visit Great Britain, so well known that it may, perhaps, to many seem almost superfluous to attempt to add anything new relating to its habits. But it is, indeed, almost impossible to study systematically any species—in fact, any organism—no matter how common, without continually adding to our store of knowledge and noticing new facts; and such facts may lead to the solution of problems connected with the mystery of life and the greater mystery of development.

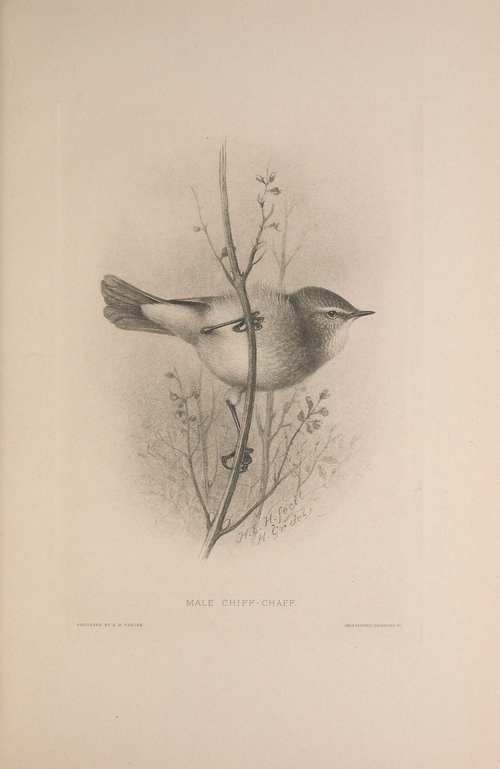

MALE CHIFF-CHAFF.

They are the first of the Warblers to arrive in these islands and the last to leave them. The earliest record of arrival I have is March 17th, and the latest April 5th. These dates refer to the West Midlands; on the South and East Coast they may arrive slightly earlier, but only slightly, since all these migrants appear to spread themselves over the greater part of England within a very short time of their arrival on the coast. This applies to the general bulk of the migrants; individuals have been seen as early as February, but these may possibly have passed the winter in some of the southern counties, where the climate is mild.

As will be seen from the dates, there is considerable variation year by year, but since the period of their arrival is frequently one of gales and very varied climatic conditions, this is, perhaps, no more than we should necessarily expect.

The migratory movement extends, as a rule, over ten to fourteen days, but here, again, we find considerable variation. In some years it will be finished within a few days of the arrival of the first male, in others there may be a delay of perhaps a week after the first one comes before any considerable numbers appear, and yet again there may be a steady increase, which is almost imperceptible day by day.

They generally reach us during the night, but I have met with small parties arriving about five o'clock in the morning; and such movements are unmistakable, for where an hour or so previously there was no sign of this species, every few acres would now hold their tiny member, each one wending his way northwards.

The welcome note of the male will be heard in the morning after his arrival; there may be fog, or there may be a cold north-east wind blowing, but no matter what the weather, there, in the tops of the highest trees, he will be, singing intermittently, a restless little fellow, looking, as he sways backwards and forwards, his feathers ruffled with the wind, almost too delicate to stand the cold; yet, apparently, he is the hardiest of his tribe, first to come and last to leave, but a greater range of food may be the cause of this. There are, however, exceptions to the rule. If, for instance, the migratory movement is interrupted by abnormal climatic conditions, such as occurred in the year 1906 on the Continent, then, when at last they do reach this country, they appear to be tired and listless, keeping low down amongst the bushes, searching eagerly for food, occasionally calling plaintively, but not singing; sometimes preening their feathers and spreading their wings and tail in the fitful gleams of sunshine, but all their movements seem sluggish, lacking their usual activity, in striking contrast to the later arrivals. If bad weather prevails—a series of gales especially, which is frequently the case at this period—then they remain low down in the bushes and hedgerows, singing, if at all, very quietly.

They do not seem to have a preference for any particular situation as a home, but distribute themselves evenly over the land, although they appear to avoid the interior of very large woods and dense larch coverts.

The male is a most active little creature, and this restless activity seems to strike one more on his first arrival, his movements are so neat and delicate, and are so fascinating to watch. One minute he may be in the tops of the tallest trees, the next down in the hedgerows, carefully examining every leaf and twig as he passes for food, which is none too plentiful, singing when he can allow himself time to do so, apparently wandering aimlessly along. But if watched very closely it will be noticed that each one, like other members of, the race, has certain well-defined hunting grounds; that although he is in the top of a tree one moment, down in the undergrowth the next, and again apparently darting away through the trees, yet he will return to the tree he started from, and so commence his rounds again.

Now this breeding territory is a matter of the greatest importance to the males, frequently leading to serious and protracted struggles when two of them are desirous of

acquiring the same area. During the first week in April I have seen these struggles commenced at daylight and carried on intermittently for two or three hours. The demeanour of the combatants, when not actually fighting or pursuing one another, shows the state of excitement they are in, for their wings are jerked about and their song is spasmodic. When actually pursuing one another their flight is extremely rapid, the birds darting in and out of the trees and bushes, sometimes high up in the tops, at other times low down amongst the brambles, and when finally they do meet, their bills click as they collide with one another, and they tumble about in the air; then, for a time, there is a pause and they retire a distance from one another. And now it is that their excitement is so apparent: it seems as if they were keeping their passions controlled with considerable difficulty.

This demarcation of their territory is best seen in long, narrow, wooded banks, which are known to be inhabited by different males; here the boundaries can be watched with greater ease. In some cases it is almost possible to draw an imaginary line, across which neither male, whose territories are adjoining, will trespass; in other cases there is a small intervening space between two territories, which again is not hunted by either male.

But in every case I have found these boundaries adhered to with the most amazing precision. Each male also appears to have some suitable position in his territory—a dead tree or perhaps some prominent larch—which he uses as his headquarters, and from which he makes little excursions into the different parts of his territory, always, however, returning sooner or later to this central position. He is therefore sometimes at one end of his territory, sometimes at the other, feeding as he travels amongst the bushes and branches of the different trees, at one moment in the tops of the highest, then low down amongst the brambles, and again on the ground, along which he moves by a succession of bounds.

Now it frequently happens that two males on adjoining territories work their way towards the same boundary simultaneously. As they approach the boundary the song becomes more frequent and very hurried, their whole attitude being one of great excitement. As they approach still more closely, this excitement increases, their wings are jerked about, the song deteriorates into a few notes rapidly uttered, they still pretend to hunt for food in a half-hearted sort of manner, but all the time it is evident that each one is keeping a close watch upon the other's movements: then the climax is reached, they dart at one another, tumbling over and over in the air, their bills clicking loudly; and, their honour appearing to be satisfied, they immediately retire to their respective territories. The final scene is not, however, always reached, for just as the excitement seems to be at its highest point, one of them commences to move in the opposite direction. Whereever there are territories adjoining, this scene, or a scene similar to what I have described, is of common occurrence, frequently being enacted by the same individuals many times during the same morning.

Whether these scenes are prompted by pugnacity or whether they are simply due to love of play I cannot tell, but there is most probably some relation between them and the importance to each individual of his respective territory. As their behaviour shows, each one is undoubtedly conscious of the approach of his rival for some distance before the boundary is reached. Whether the fight or game only takes place when one actually crosses the boundary I have not been able to determine.

A male that has recently arrived often passes through the territory already adopted by some earlier arrival, and his behaviour under these circumstances is instructive. He creeps amongst the bushes low down, almost in the undergrowth, not singing, but occasionally uttering a note, apparently anxious to keep out of sight. It is, however, seldom that he remains long undetected by the keen eye of the owner, who immediately starts in pursuit, darting after him with very rapid flight, and chasing him often for some distance beyond the confines of his territory. The interesting part is that the new arrival does not always retaliate, but accepts the situation, as if instinctively conscious that in thus trespassing he was sinning against the unalterable laws of the species.

These territories are sometimes curiously situated. I remember one in which there was a space of about two hundred yards of bare ground between two small coppices, both of which were included by a particular male in his territory; thus he was continually flying backwards and forwards. At one end a sycamore tree (Acer pseudo-platanus) conveniently placed supplied him with food, for numerous Chironomidæ clustered under the leaves, which were somewhat early developed; here he was quite happy hunting and singing for ten minutes or so, then, suddenly darting off, he would rise to a considerable height in the air and make straight for the opposite coppice, returning again shortly in the same manner.

In the early part of the season the difficulty of obtaining food is, no doubt, the dominant factor of his movements; he can then often be seen searching the low holly-bushes, examining the undersides of the leaves very carefully, and a close inspection of these leaves will reveal the Chironomidæ, not in any great, but quite appreciable, numbers. These small flies are evidently the cause of his great activity, but, compared to their numbers a month later, they are few and far between, and for this reason he examines certain trees much more minutely than others, as, for instance, solitary larch (Larix Europæa), the hollies (Ilex aquifolium), some species of willow (Salix) that grow by the waterside, and especially small patches of sprouting hawthorn (Cratægus oxyacantha).

Until the trees are in leaf he roosts in any conveniently warm spot, such as clumps of ivy, thick bramble, &c, retiring to his quarters soon after sunset. When actually roosting he is fearless and not easily disturbed. I have thus approached within a few feet of one, and have found that though quite alert and watching my movements closely, yet the relaxed feathers were not drawn close to the body, showing a complete absence of suspicion. At this time of year he is by no means an early riser; if, indeed, the morning is dull or cold he is decidedly late.

For the ten days or so before the females arrive he is not as playful as later on, but seems to take life more seriously; yet at times he is most excitable and evidently keeps his passions under control with some difficulty, for I have seen a male sitting on a branch, jerking his wings and uttering his courting note, although no female had at that time arrived.

The first arrival of the females takes place from ten to fourteen days after the first male, the date varying in different seasons from April 5th to April 22nd. This, however, does not imply that the migration of the males has ceased, but that, although the first arrivals are always males, the migration of the sexes overlaps. It is often the case that individual males are still arriving while the courtship is actually proceeding. The first males to arrive are by no means the most beautiful, as we might be led to expect, neither does the evidence point to any natural law, which would imply their adherence to any fixed rule in the order in which they migrate, such as the older birds, or the most healthy and therefore, perhaps, most beautiful, arriving first. I am almost inclined to say that the later arrivals on the whole have the richest plumage—in thus speaking I refer to all species of migrants—but the evidence is of a very conflicting character. Take the case of any migrant, and I can recall seasons in which the earlier arrivals have been individuals in the most exquisite plumage, and seasons in which they have been immature, with plumage undeveloped. In some years I have even noticed brightly coloured males arriving after all the courtship was finished. This is why I speak of the evidence as conflicting, and in order to arrive at any definite decision a much more accurate knowledge of the details is imperative.

The migration of the females continues for about fourteen days, and this results in the nesting operations of certain pairs being temporarily in advance of those of others. In one case the courtship may be finished and the nest even built and lined ready to receive the eggs, while another male close at hand may still be without a mate; but in this latter case, when the female does at last arrive, the courtship is quickly finished and the nest, as I shall mention later, more rapidly built. Much time is therefore gained, and it will be found, in consequence, that there is ultimately little variation in the dates upon which the young of different pairs are hatched.

On their arrival the females seem to prefer the bottoms of the hedgerows, thick undergrowth, or low positions of some description to the taller trees; it is difficult to see the reason for this, especially as it is only the case on their arrival, but it may, to some extent, facilitate the courtship, which is immediately commenced.

As might be expected from such active and lively little creatures, the courtship is an exceedingly interesting and also a very beautiful one, and in order to see it at its best it must, as in the case of every bird, be watched during the first few hours of daylight; it may proceed to a limited extent during the daytime, but I have seen no sign of this, neither do I expect to do so, for all birds at this time of the year rest and are dull in the middle of the day, and although they become more active towards the evening, yet this activity cannot be compared with that which exists during the first few hours of daylight.

The female generally arrives during the night, and directly there is sufficient light the male in whose territory she has settled commences to court her. The duration of the courtship varies to suit the needs of each particular case; on the one hand, a pair may be courting in the mornings for some days, and, on the other, the differences are quickly settled, and they apply themselves to the task of nidification.

During the actual courtship the female, moving quietly from place to place, calls loudly and continuously with a very plaintive long-drawn note to the male who follows her; off and on he darts at her with a very quick flight, resulting in a mimic battle, but although the clicking of their bills as they meet is plainly audible, yet it is not difficult to see that it is all a game, or rather part of the wooing.

If it is in the tops of the taller trees that he is following her, she works her way gradually, as she moves along, lower and lower down even on to the ground, where she hops about; but he, while she is here, not being able apparently to carry on his courting, moves away in search of food, and this they both do for a time contentedly, each in his or her own direction. But they do not seem to be able to do without one another's companionship for long, and so perhaps she will call to him—a call he very soon answers—or while calmly feeding a sudden impulse seizes him, and he darts off headlong to find her. This time he may be more active in his courtship, and, following her closely with quivering wings, utters a curious buzzing sound; another time he will float towards her through the air, like a very big moth, with his wings outstretched and slowly flapping. This is one of the prettiest aspects of the courtship, especially when, instead of floating straight towards her, he approaches her in semicircles: the great beauty of it lies in the way in which he beats the air with his wings; this he does so very slowly as to give one the impression that he ought not to be moving at all. In any attempt, therefore, to portray this, the principal beauty is lost.

In this manner of courting he is not alone, for Blue Tits (Parus cæruleus). Hedge-Sparrows (Accentor modularis), and Lesser Spotted Woodpeckers (Dendrocopus minor) do the same thing. When floating through the air he sometimes utters a curious note, but is more frequently silent. Other positions assumed during his courtship are also very beautiful, the feathers often being raised and fluffed out. One position

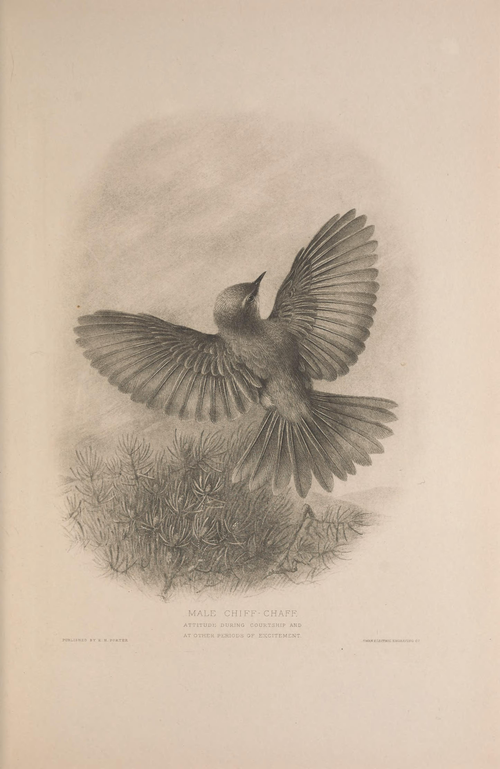

MALE CHIFF-CHAFF.

ATTITUDE DURING COURTSHIP AND

AT OTHER PERIODS OF EXCITEMENT.

is especially striking; sitting in a very upright position he raises the feathers on his head and back, the latter being thus much rounded, throws his breast feathers forward, swells out his throat, carries his wings rather loosely, giving himself the appearance of a round ball of feathers, spreads out his tail as far as possible and moves it sideways very slowly; this latter feature is curious, for he never at other times moves his tail in this way, herein differing from such birds as the Red-backed Shrike (Lanius collurio) and Redstart (Ruticilla phœnicurus), who habitually make use of this side-long motion when excited.

During the period of courtship the males are apparently very quarrelsome, but the possession of the female does not appear to be the direct cause of their battles; perhaps they are not battles but only games; this is most difficult to decide, for they are frequently so vigorous that the impression left on one's mind after watching them is that of a severe fight. Their flight when pursuing one another is very quick, entirely different from their ordinary one, and the way they dart in and out of the trees is quite amazing, the pursuing male as he flies often uttering the two notes, of which his song is composed, very quickly; and at other times both pursuer and pursued use the same buzzing note as during the courtship. The actual fight generally takes place in the air, the clicking of their bills as they meet one another being quite loud. When standing close to them during these struggles they have sometimes fallen within a few feet of me, and as they tumble, locked together, through the air, twisting slowly round and round, they look like a mass of feathers devoid of all form; upon reaching the ground they lie for a few seconds exhausted or surprised, then fly quietly away, each in his own direction.

Nidification commences about the middle of April, soon after the courtship has taken place. The exact time varies, and the rapidity with which the nest is built varies correspondingly with it; sometimes the nest is commenced in a lazy sort of way, a little being added to it each morning and nothing during the day; at other times it is built hurriedly, the female flying backwards and forwards with grasses and leaves, often two or three of the latter at a time, fixing them with wonderful rapidity. The cause of this great haste in the latter case is evidently the advanced development of the ovaries, by which she is no doubt guided. She alone, or nearly so, does all the building, the male taking little or no notice of her, sometimes being rather more of an annoyance than a help, flying after her in a playful manner while she is at work searching for materials. These materials she collects close round the position which has been chosen for the nest, and she often searches for them repeatedly in the same spot. Sometimes when busy building she is remarkably fearless and seems little concerned at one's presence, only calling plaintively now and again as she flutters round, carrying, with apparent difficulty, leaves as large as herself.

The nest is generally situated from three inches to three feet from the ground. I use the word "generally" because, though I have never actually seen one on the ground, I have found them so near as to only just allow sufficient room for my fingers underneath. Therefore I should not be surprised to find one built there, as the Willow Warbler's is. It is sometimes placed in the middle of thick bramble bushes, or on the side of a bank, supported by dead grass and small entwining branches, or in clumps of dead grass on the level, or, again, in masses of nettles and herbage intermingled. There does not, however, seem to be any preference for any particular situation, nor even for any particular herbage, but the positions are apparently chosen indiscriminately, so long as they are well concealed.

The nest is an exceedingly pretty one, dome-shaped, with the entrance at one side rather near the top; the outside is composed of dead leaves, chiefly mixed with some of the coarser dead grasses; next to this, dead grass forms the principal material mixed with fine roots; next to this, again, is the lining, which is composed of feathers only; but it seems that close to the lining finer and more delicate grasses are used than in the outer parts. The lower portion of the nest is more stoutly built than the upper, and the dead leaves are more securely glued together. The eggs are usually six in number.

I have already mentioned that the male takes little notice of the female after they are paired. This is more marked during the time she is laying and incubating; his attention during the former time is almost wholly limited to the periods immediately preceding coition, and during the latter this attention dwindles to almost nothing. When the female comes off the nest she is often pursued by the male, who, when close beside her, throws out his feathers in a similar manner as when courting; at other times she sits on a bramble calling continuously in an excited way, with her wings rapidly quivering; he then darts at her, pursuing her with rapid flight and playing with her in the air, the two of them often falling to the ground from the tops of the highest trees.

There is much evidence to show that coition depends solely upon a certain condition in the female, for I have noticed that, during the period in which a bird is laying, it takes place generally when the female leaves her nest in the morning, less frequently in the evening, and usually at about the same time. Now whereas it often happens that the male makes overtures to the female, which are allowed to pass unheeded or which are sometimes even resented, yet directly the female is in the condition referred to, and displays it to the male, coition takes place. The attitudes indicative of this condition, and by which the female does undoubtedly display it to the male, vary in different species, but are at all times unmistakable—the arched neck and slow but stately walk of the Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus), the quivering wings and raised head and tail of many Passerine birds, the outspread and slowly flapping wings of some of the larger species, such as the Rook (Corvus frugilegus): these all bear witness to the excitement under which the bird labours. It seems, therefore, that Nature does exercise an effective control over the passions of both sexes of many species in this way, i.e., by the necessary condition of the female only arising at certain definite times, and in her case this control is by some means direct, depending upon internal processes, but in the case of the male indirect, though none the less adequate.

The life of the male from the time that the female commences to lay is a most methodical one; this seems to be the rule of the whole species, and I can nowhere find any deviation from it. He adheres with wonderful precision to the boundaries of his territory, where he can be seen morning after morning in the same tree, pouring out his monotonous song, through May, June, and the greater part of July, even after the young have left their nest and disappeared—some, perhaps, to their winter homes. Not, indeed, till the latter part of that month is there any perceptible change, the first intimation of which—the approach of the moult—is a gradual deterioration of the song. He still, however, keeps to his territory until the end of July, when, warned perhaps by the inevitable change that is taking place in him, he begins to move away and wander into hitherto unexplored land.

During the whole of this period referred to he lives exclusively in his territory, and is most jealous of the intrusion of any other male, fighting him vigorously, the female even joining in the pursuit. As the weeks pass by these combats become so frequent, occurring again and again during the same morning, that I am inclined to think they are prompted largely by a love of play. If this is the case, and they are games only, then they are indeed exceptionally vigorous ones, differing only in their duration from the fights which take place earlier in the season over the possession of the breeding territory. There is no doubt about the genuineness of his excitement, for on the approach of the other male he jerks his wings and spreads out his tail, hops hurriedly from branch to branch, all the while uttering a curious squeaking note ending with a rattling noise in his throat; then, suddenly starting off in pursuit, he darts in and out of the trees, singing hurriedly as he flies, and on coining up to his rival seizes him, and they both tumble over and over in the air or on the ground. Sometimes, however, changing his mind in the middle of the pursuit, he turns suddenly in the air and returns quietly to his territory. To notice his behaviour towards other species who trespass in the same manner is interesting. I have seen a territory invaded by a family of Blue Tits numbering eight or nine; these Blue Tits passed the same way on their travels for three consecutive mornings almost at the same time. This seemed to be a grievance and a source of real annoyance to this particular male, but he was evidently afraid of their numbers. Darting about, he would spread his tail and rapidly jerk his wings, now and again chasing an isolated member of the family in a half-hearted sort of way, sometimes even venting his anger on a solitary Whitethroat, but finally, leaving the Tits in possession, he would retire to the other end of his territory, from whence he would only return after they had departed.

On the approach of a Hawk he will sometimes fly out of the tree he is in, beating the air very slowly with his wings, hanging his legs down, and uttering his high, squeaking note; his behaviour being in every way similar to that during courtship. He keeps, in fact, a very close watch on all birds that pass near him, frequently chasing Cuckoos (Cuculus canorus) determinedly away, and even if he gets a glimpse through the foliage of a bird passing above him he starts off in pursuit. But he is not so bold as he at first sight appears, for should the stranger, resenting his pursuit, turn and face him he immediately retires.

During incubation the female leaves her nest as little as possible, and evidently has regular times for so doing; frequently between 5.30 and 6.30 in the morning.

The young are hatched about the first week in June. Both parents take part in the feeding, but of the two the female is far the more industrious, the male helping, if at all, very little, but keeping instead a jealous eye on any intruder, allowing his suspicions to be allayed only with the greatest difficulty. Owing to the position of the nest, it is often most difficult to get sufficiently concealed to allow the parent birds to feed their offspring and clean the nest perfectly naturally; and in order to obtain accurate knowledge of the mysteries of their nursery, especially with regard to certain problems relating to the order of feeding the young, the actual food that is brought, the condition in which it is delivered to the young, and the possibility of different food being supplied by the male and female respectively, it is necessary to be within a few feet of the nest. For instance, if the female cannot overcome her suspicion of you she will not feed naturally, her whole aim, under such circumstances, being to get rid of the food. This, then, is the difficulty, and can only be overcome—and this by no means always—with considerable patience. In this endeavour the dome-shaped nest adds largely to these difficulties. When the young are first hatched the female appears to be very excited, darting backwards and forwards round the nest: the male, taking advantage of her light-heartedness, pursues her and plays with her after his manner in the air. The care of the young is no great labour to her at first, but it increases daily, until it becomes a matter of some difficulty for her to keep them fully supplied with food.

Each day the brooding of the offspring becomes of less, and the food supply of more consequence, yet the male never seems to think that his services are really required, feeding the young only occasionally as it suits him. I have, however, seen him bringing food to the female when brooding early in the morning, and when doing so he would sing quietly right up to the nest itself. On the other hand, she commences to feed

MALE CHIFF-CHAFF.

ATTITUDE DURING COURTSHIP

her brood in the morning as soon as there is sufficient light, about a quarter to four, that is to say, an hour or so after dawn. Her routine of feeding alters day by day, according to the growth of her offspring. For the first day or so she will bring one supply of food, then remain on the nest brooding her young for a period of about twelve minutes, then again go in search of the one supply, and so on. During the next stage, when the young are a few days old, she will bring food twice or perhaps three times, then remain on the nest for the same period as before; thus the food supply increases day by day until it becomes almost continuous. I have carefully noted the actual time spent in brooding her offspring, and have found this period of twelve minutes adhered to with remarkable accuracy, varying only a minute one way or the other. The fæces is carried away, but not each time that food is brought, and deposited some distance from the nest, or else eaten.

She frequently uses her call-note when approaching the nest, but this may be due to my presence. When on the nest brooding her young she sings quickly and quietly to herself—this often just before she leaves the nest—and it sounds very much like a quiet purring note, which can be heard only a few feet away.

Her nervousness at any human presence varies very considerably. If you take up a position near the nest at dawn before she leaves it, she will not be so nervous; if, on the other hand, you are later and arrive while food is being brought, she will sometimes be more nervous, resenting your presence; and again, after you have been there some considerable time, she will suddenly be seized with a nervous fit, which takes her some time to overcome; thus she will work backwards and forwards up to the nest, approaching even to within a few inches, and as rapidly retreating, but unable apparently to summon up courage to make the final effort to reach it.

It is interesting to notice the manner in which the nest is approached. This varies according to the situation, but in most cases the remarkable tendency towards fixed habits, of which I shall speak presently, is in evidence. On her way to the nest she glides each time under the same bramble, perching always on the same twig, and when hidden from view her progress can still be marked by the same leaf shaking here, or the same nettle swaying there, until the nest is finally reached and her entrance disclosed by the usual movement of twigs around. Why this careful approach? Can it be for the better protection of the young? Is it, therefore, a means to an end? These are difficult questions, but perhaps the best reply is in the way in which she leaves it; for instead of doing so in the same careful manner, she flutters out through the foliage and undergrowth, making such a rustle as would ensure her movements attracting attention.

For so small a bird the young are a long time before they are fledged sufficiently to leave the nest, the exact time being about fifteen days after the first young one is hatched.

I have sometimes speculated as to why the nestlings of some species develop more rapidly than those of others. Is there any difference in this respect between those species that build open nests and those that do not? Is the slow development confined to those species in which one parent bird only supplies food? If these questions can be answered in the affirmative, then we may attempt to explain either the indolent habits of some males, or the habit of building covered nests, by simple cause and effect; but I have not had sufficient time to investigate it fully.

Until the young are able to follow their parents properly, they keep low down in the bushes and undergrowth, often even on the ground. This must be an anxious time for the mother, as enemies abound, and the young are generally scattered. However, after a few days, being able to fly with rather more strength, they gather together again and keep higher up in the trees; and now they can often be seen sitting in a row, some facing one way, some another, evidently for warmth and comfort, since they are always most anxious to get as close to one another as possible. It is a pretty sight, and a most instructive one, to see the young following their parents, travelling from tree to tree, continually being supplied with food by the indefatigable mother; but they are more easily watched in gardens, which they frequently inhabit, searching the roses for the larvæ of different moths. The systematic way in which they travel through a rosebed is interesting, and the number of larvæ they consume astonishing. They seem to look upon those insects as a special delicacy, and for this reason alone, if for no other. I consider them some of the best natural gardeners we have.

The female is most pugnacious during this period when any common enemy approaches too closely, nor does this pugnacity decrease so long as her offspring are still under her care. When watching her on one occasion feeding her young, who were quite able to fly and thus escape any ordinary danger, I saw a Missel-Thrush settle on a very tall elm tree some distance away and commence to jerk his tail and chatter in a perfectly harmless manner, evidently with no evil intentions. He did not seem even to be aware of the presence of the Chiff-chaff and her family, who, however, appeared to resent his proximity, for, leaving the bushes, she flew straight up like a rocket to the top of the elm, and attacked the Missel-Thrush so vigorously that he at last flew away, pursued for some distance by the irate mother.

The male, although taking little or no notice of the young, does not leave his territory, as I have already mentioned, until towards the end of July. About this time both young and old often join the small flocks of Tits and different species of Warblers, which, roaming from field to field, travel thus in search of food—a merry party. The young have ample scope here for their playfulness, chasing whatever species happens to be nearest to them, whether Tit or Warbler. The adults are still the same restless, independent individuals, not so much following the flock, but rather taking a line of their own whenever an occasion arises. Thus you will find them in fields of beans or potatoes, appearing on the top of a plant one minute, then disappearing, only to appear again fifty yards or so away; and again, you will see them in hedgerows or in the taller trees, anxious to join in any game or fight, for food is plentiful and family cares have ceased.

In August, during the moulting period, they are much quieter, only singing occasionally, but in September they, together with the young birds, commence to sing again. Now also, they begin to think of migrating, gradually decreasing in numbers during the month, so that by the first week in October few are left.

A second brood is sometimes reared in the same season. Whether this is due to the first brood being destroyed I cannot say, but I have frequently seen the female tending her young in August.

During the last autumn days that they spend with us they are still active and full of vigour, singing a good deal, and ready to play with one another, or, indeed, with any other bird that happens to cross their path. Abundance of food and no work is probably the cause of this burst of activity; in addition to this they have finished their moult, and are therefore in the best of health.

During their games they sit facing on opposite branches with quivering wings, then, darting at one another, they play in the air, their bills making the usual clicking noise. Tits come in for much teasing, and I have been amused to notice that the Blue Tit is held in much higher esteem than the other members of the family. A pretty sight it is to see one of them playing with a Blue Tit; the Tit clinging on to an upright sprig, looks down with contempt at the Chiff-chaff: a foot or so below, clinging to the same sprig and looking up, trying to make up his mind to attack.

Interesting as everything pertaining to the life of this species is, there is one distinctive characteristic which is always prominent; this is a highly developed nervous temperament, leading often to acts of apparent inquisitiveness. I shall quote a number of cases showing under what very different conditions this characteristic is aroused.

If any commotion is going on in the feathered world, the little fellow will come down from the tree-tops, and, if you stay motionless, will flit round you with an air of importance, uttering his plaintive whistle.

When one is examining the nest of a Song-Thrush, in which the young are only just hatched, the old bird will call loudly and piteously; this is a sure attraction.

One year, on May 12th, I was watching a pair of Nightingales mating, and while doing so disturbed a Weasel. The Nightingales at once noticed it, and, ceasing their courtship, settled, regardless of me, on the branches near, and commenced to croak vigorously, flirting their tails up and down. This at once attracted a Chiff-chaff, who flitted round, adding to the noise as much as he was able.

Early one July I was searching for the nest of a Flycatcher. The birds were very much excited and, calling loudly, flew round my head; a Chiff-chaff immediately came down and behaved in the usual way.

When Whitethroats have been courting I have seen him interfere in a most unwarrantable manner, also when the young of the same species have been engaged in their harmless games.

To the scolding parties that are to be seen amongst the Sedge-Warblers he is a frequent visitor.

A more curious case is the following: Two male Blackcaps, who had that morning arrived, were engaged in a frantic struggle for their breeding territory. They were flying at and pecking one another vigorously. While thus engaged a Chiff-chaff flew down from the trees and joined in the fray, attacking first one, then the other, indiscriminately. During the pauses in the contest he would hop round excitedly, watching the combatants closely, and whenever the fight recommenced he would immediately join in, the clicking of all the bills making quite an unusual noise.

These examples show under what diverse conditions the inquisitiveness occurs, and all members of the species appear to be equally susceptible to the same stimulating circumstances. By the use of the term "inquisitiveness" I do not wish to imply an intelligent appreciation on the part of the bird of its various actions; the construction intended to be placed upon it is a figurative one, the purpose being to make clear the type of action when viewed from the human standpoint.

It is so generally accepted that plasticity of instinct[2] has been established as a law of Nature that I almost refrain from questioning the correctness of this view; nevertheless, the more I reflect upon the facts, which I have from time to time collected, the more I feel disposed to regard as doubtful, not so much the possibility of isolated cases of variation arising, though there is little evidence in support of this, but whether the extent to which it has been thought to have been shown that they do occur, is sufficient to justify our accepting such a law as beyond dispute. Owing, perhaps, to the great difficulty of establishing this on the basis of actual observation, it seems to have been assumed too readily that they do occur, but whatever difficulty there may be in this direction can only arise from the rarity or possible absence of true variation, and we ought on this account to be very cautious before arriving at any definite decision.

MALE CHIFF-CHAFF.

ATTITUDE DURING COURTSHIP.

Although a critical investigation of the complex and divergent activities of the lower animals lends so little support to this theory, it reveals abundant evidence of a law of uniformity extending to all the varied incidents of the lives of the different individuals of the same species, the magnitude and importance of which, so I am inclined to believe, has been obscured by an incessant quest for variation. It is only when we carefully consider the conditions of existence of most species, and understand how favourable those conditions are to any innate modifiability, that we can appreciate the full significance of this law. So favourable, indeed, are they that it has often seemed to me a remarkable fact, and one very difficult of explanation, that individuality is not of frequent and persistent occurrence. Let us take the case of the Chiff-chaff. After reading of the way in which it examines and joins in the various disturbances around, the manner in which the breeding area is fixed and adhered to, the choice of a certain tree as headquarters, and the systematic working towards the boundaries, culminating in a combat or game with its neighbours, no one, I imagine, will deny the variety of its activities nor the complicated movements involved in such activities; but, in addition, this bird possesses vigour in excess of its immediate needs in a greater degree than many other species, resulting in a pronounced restless energy and ceaseless activity. In such an existence as this we must believe that opportunities for modification will constantly arise, yet apparently no individual attempt is made to depart from the rules of the species, for we find that, in so far as the systematic study of different members of the same species enables us to judge, all these activities, both simple and complex, are similarly performed under the same appropriate circumstances by all the individuals of the same species.

And pursuing the subject somewhat further, if we not only accept variation as an established fact, but look upon intelligence as the principal factor, as it is so regarded by many, then the attempt to explain the stereotyped uniformity, which we everywhere see around us, becomes even more difficult. Are we to suppose that the standard of intelligence has remained stationary, while by its assistance, instincts have been gradually built up or modified to suit changed conditions? We cannot do so. For if such a faculty is really innate, it must have been, and must be still, subject to the same laws which have been responsible for the development in every other direction; it must therefore be more potent to-day than yesterday; it must, in fact, have developed pari passu with the selection of the more adaptive activities for which it has been responsible. I do not, of course, wish to imply an intellectual progress akin to that in human life, but a more highly elaborated perception and an increased capacity for taking advantage of opportunities as they arise, and the result of this would necessarily have been a corresponding increase in divergent individualism, and we ought in some measure to be conscious of the transitions and of the repeated attempts on the part of different individuals to depart from the normal type of activity. But this is not the case: the law of uniformity, in fact, precludes the possibility of it. We are therefore forced to conclude that if intelligence has really been operative, it has at the same time been unprogressive, while in every other direction progress has been made, and this I cannot believe.

The importance of placing this question of individuality, with its far-reaching effects, beyond dispute cannot be overestimated, since it directly affects the question as to whether animal species display any traces of intellectual development from generation to generation, and, indirectly, the possibility of a progressive development from animal to human intelligence, and consequently the whole subject of the genesis of mind. The final solution must rest with those naturalists who will devote themselves to the study of one, or at the most a few, species.

This uniformity seems to extend to all the activities, whether referable to instinct or habit; but at the same time there are incidental details connected with them which vary in each particular case, and in what manner they are carried out can only be determined by each individual as the need arises. It is while performing these details that I have noticed a remarkable tendency towards the formation of fixed habits, a tendency to repetition. I mention this here because it may bear some relation to the law of uniformity.[3] It is of common occurrence in Nature. I have referred to it in the way in which the Chiff-chaff approaches the nest, but other birds have the same habit. When searching for materials to build their nests, birds frequently return to the same spot, although such material could be gathered more conveniently; and in the same way they return again and again to the same place for food; the Great Spotted Woodpeckers (Dendrocopus major) are a good instance of this, for they often have their rounds, consisting of certain trees, which they visit in order daily; families of Tits also have their rounds. We find the same thing in the accurate measurements of periods of time, but more conspicuously in the way in which the same branch in a certain tree in the breeding territory is utilised as the headquarters. A better illustration is the manner in which the same birds repeatedly return to the same situation for the purpose of breeding. A number of Martins (Chelidon urbica) build against my house in such a position that their nests are washed away by any heavy rain, yet they return year after year. It is impossible to prove that the same birds return each year, but this is really unnecessary, since the nests are built up and washed away a number of times during the same season, and each time the same position on the wall is chosen: only in an occasional instance are the young successfully reared. These cases are. I think, sufficient to make clear my meaning; but no doubt a number of similar ones will suggest themselves.

Their food is principally insects and their larvæ. I have not seen them feeding on berries, although they spend considerable time in the autumn hopping about amongst the elder bushes (Sambucus nigra) when the fruit is ripe. On their arrival in March and during the first part of April their principal food is Chironomidæ. In pursuit of these insects they search minutely the under side of the leaves of different evergreens, such as holly, ivy, &c, and the trunks of the larger trees, upon which these flies frequently cluster, almost the only species sufficiently numerous, during the cold east winds, to afford food. In April also they search the bare branches and trunks of the different trees for the young stages of Psocidæ, minute white insects, which can only be identified by a very close examination. It is insects, probably Chironomidæ, that are the cause of their searching the grass on lawns, where they hop about hunting the ground very quickly. They can sometimes be seen clinging to the trunks of apple trees in order to pick off the small moth-like flies of the genus Psychoda. In May and June they take quantities of the larvæ of Chimatobia brumata and Tortrix viridana. This latter insect, the oak leaf roller moth, causes very great destruction in some years to the oaks. If you stand under one of these trees some warm evening in May you will notice that the foliage is everywhere riddled, blighted, and partially destroyed by the larvæ, and that the undergrowth is covered with their excrement. Now watch these little Warblers, together with Whitethroats, Willow-Warblers and Blackcaps, at work; notice their insatiable appetite and the energy with which they seek their food; thus we come to understand the danger

FEMALE CHIFF-CHAFF.

ATTITUDE DURING COURTSHIP.

of any undue interference with Nature, and at the same time realise, in some small degree, the vastness of the natural laws that are in force around us. To the fruit grower, and especially to the rose grower, these birds are invaluable. To watch them hunting a garden is an education in itself.

The young are principally fed on the larvæ of the abovementioned insects, and to some extent on Chironomidæ and Tipula oleracea (Daddy-long-legs). When old enough to follow their parents in gardens or amongst the oaks, their appetites are almost inexhaustible. Both old and young find food on the bare ground, for they are fond of searching between the rows of peas, and also in the potato drills. In the autumn they spend considerable time amongst the willows, the reason probably being that insect life is daily becoming scarce, and it is consequently more likely to be found in damp places where the different species of salix grow. It must not be supposed that this list exhausts the food supply of the species, but it constitutes a very large part of it. It will be noticed that it includes two of the most destructive pests—Tipula oleracea and Chimatobia brumata; I need not, therefore, enlarge further on the benefits this species confers on agricultural interests generally.

The song, from which they take their name, needs little description. As the summer advances it becomes rather monotonous, for they are the most persistent of singers, seldom silent, except in the middle of the day and during part of August. When they first arrive in the spring it is rather more vigorous. It consists of two notes, one rather higher than the other, but the first note is sometimes uttered two or three times before the last; also there is often at the beginning and end a curious little medley, rapidly and quietly uttered. I have never heard one really attempt to imitate another species, although I remember hearing one male with a song like a Cole-tit (Parus ater), but this song was mingled with the ordinary notes.

- ↑ This photogravure plate, intended for Part 2, was published late, in Part 3, with a loose slip noting the delay included in Part 2, in its intended position (Wikisource contributor note)

- ↑ Anecdotes of animals in a domesticated or semi-domesticated state have furnished most of the evidence upon which this theory is based. This is much to be regretted, since it tends not only to confuse the issue, but also to transfer attention from the only true source of information available, viz., an impartial investigation of wild Nature. It must be borne in mind that the question to be solved is not how far instinct can become plastic under a guiding human intelligence, but what method is adopted by Nature, and has been adopted ab initio. Even the very animals from whose actions evidence is taken are indirectly the outcome of human faculty.

- ↑ Darwin refers to this tendency in the "Descent of Man" as follows: "There seems even to exist some relation between a low degree of intelligence and a strong tendency to the formation of fixed, though not inherited, habits; for, as a sagacious physician remarked to me, persons who are slightly imbecile tend to act in everything by routine or habit, and they are rendered much happier if this is encouraged."