The Celtic Review/Volume 3/Alexander Macbain

Deep and widespread sorrow attends the death of Alexander Macbain, LL.D., so well known as one of our foremost Celtic scholars. The sad event was startling in its suddenness. Dr. Macbain was only in his fifty-second year; he left Inverness, with which his name has been so long honourably associated, on Wednesday, 3rd April, in his usual health, on business connected with the promised new edition of his Gaelic Etymological Dictionary; on Friday afternoon came the news that he was no more. He

had died on Thursday night, of cerebral hæmorrhage. In accordance with his own desire, his body now lies in the lonely churchyard of Rothiemurchus in his native Badenoch, under the shadow of Cairngorm.

It is difficult for his friends, with the echoes of his voice still in their ears, and the picture of his familiar presence still fresh in their minds, to realise that he is truly gone. It is more difficult at this moment to appraise his life's work, as teacher and as man of science. Defect here is inevitable and perhaps matters little after all. For his was no bubble reputation, but one that will assuredly stand the test of time; and as long as Celtic language and literature are studied, Macbain shall have his due.

Alexander Macbain was born in Glenfeshie, in Badenoch, Inverness-shire, on 23nd July 1855. His father was John Macbain. The Macbains belong to the great Clan Chattan, and are proud of the fact. His early years were spent in Badenoch as pupil and as teacher. He served for a short time with the Ordnance Survey in Wales. In 1874 he entered the Grammar School of Old Aberdeen, famous then under the Rectorship of Dr. William Dey as a preparatory school for Aberdeen University. Two years thereafter he entered King’s College as second bursar. He is said to have impressed his fellow-students as the ablest man of his year, a year which included James Adam, now of Emmanuel College, Cambridge, and our foremost platonist. Though a good classical scholar, Macbain read for honours in philosophy, a subject which in after life he reckoned one of the most barren of studies, and graduated in 1880. For a short time he assisted Dr. Dey in the Grammar School; thereafter, in 1880, he was appointed Rector of Raining’s School, Inverness, under the government of the Highland Trust. He occupied this post till 1894, when Raining’s School was transferred to the Inverness Burgh School Board. Since then he has been officially connected with the Secondary Department of the High Public School. In 1901 his University of Aberdeen honoured him with the degree of LL.D. In 1905 Mr. Arthur J. Balfour, then Prime Minister, in consideration of his great services to Celtic, and specially Gaelic, philology, history, and literature, recommended him to the King for a Civil List Pension of £90, to date from 1st April of 1905.

As Headmaster of Raining’s School, Dr. Macbain exerted an influence over his students very similar to that of his own old teacher, Dr. Dey of Aberdeen. He taught them to think for themselves, to insist on having not only the facts but also, wherever possible, the reasons why these things are so. The students of Raining’s School, lads drawn from all quarters of the Highlands, were not slow to kindle at their master’s quickening fire. They gladly lived laborious days and nights, doing with all their might that which was given them to do. Under such conditions it is no wonder that Raining’s School became a nursery of students who subsequently took the highest position in the University classes, and became useful and distinguished men in their various callings. Some idea of their numbers may be formed from the fact that the annual re-union of old Raining’s School boys became a regular function in Edinburgh. There their enthusiasm for their former master found expression, for the great feature of these gatherings was the presence of Dr. Macbain.

While thus actively and successfully engaged in the work of an arduous profession, Macbain was at the same time carrying on with extraordinary vigour those Celtic studies which won him a world-wide reputation. When he came to Inverness in 1880, the scientific study of Scottish Gaelic had already begun under Dr. Alexander Cameron, of Brodick (ob. 1888), but little substantial progress had been made. In February of 1882, in his first speech at the annual dinner of the Gaelic Society, Macbain said, ‘Hitherto the Highlanders have been too much inclined to guess, and too little inclined to accurate scientific research. We want a good critical edition of the Gaelic poets; we want also a scientific Gaelic Dictionary dealing with the philology of the language.’ He was then twenty-seven. For this work he set to qualify himself under great difficulties. He lived far from a university town, and far from libraries. The books he used were expensive, and he had to learn French and German to read them, for very little of real value had been done in English. Worst of all, the work had to be done after a hard day’s duty had already been accomplished. In spite of all Macbain toiled on. His philological work was only one part of his output. His first paper to the Gaelic Society of Inverness was contributed on 21st February 1883, on Celtic Mythology. Thereafter he is represented by important papers in every volume of the Society’s Transactions from vol. x to vol. xxiii. inclusive, except vol. xv. His contributions—apart from valuable and informative speeches at the annual dinners—number eighteen in all, and all may be said to be original, and in a greater or less degree foundational. Perhaps the best known of these are his edition of the Book of Deer (vol. xi); Badenoch History, Clans, and Place-Names (vol. xvi,); Ptolemy’s Geography (xviii.), the last of which he himself considered ‘the best thing he had done’; and the ‘Norse Element in Highland Place-Names’ (xix.). In addition to these papers, he wrote that valuable series of introductions to the volumes of the Society’s Transactions from vol. x. onwards, which constitute a history of Celtic literature and of the Gaelic movement for the period covered by them. To the Transactions of the Inverness Scientific Society and Field Club he contributed three papers of great importance–‘Celtic Burial’ (vol. iii.); ‘Who were the Picts?’ (vol. iv.); ‘The Chieftainship of Clan Chattan’ (voL v.). When it is remembered that, in addition to this, Macbain became in 1886 editor of the Celtic Magazine, and was also for five years joint editor of the Highland Monthly, to both of which he contributed much, besides generous contributions to local newspapers, some idea may be formed of the energy and activity of the man during those years 1882-1896.

In each of his articles it was his habit to get to the bottom of a subject, and so far as he could to exhaust it. In all this output there were naturally points that subsequent research showed to need modification or correction. For instance, he departed from the views of Celtic mythology which he had enunciated in his first paper to the Gaelic Society. But in view of the quantity of his work, its originality, and its difficulty, such points are surprisingly few. So far as known to me, apart from the article mentioned above, they were mainly interpretations of place-names. In 1892 appeared his edition of Reliquiae Celticae (two volumes) in conjunction with Rev. John Kennedy, Caticol, Arran, being the literary remains of the Rev. Alex. Cameron, a work which has roused the admiration of all competent critics. His Etymological Gaelic Dictionary appeared in 1896. This was his greatest and crowning achievement, and was at once recognised as marking an epoch in Celtic philology. Since its appearance he has edited Skene’s Highlanders, with most valuable but all too brief notes. He has also, in conjunction with Mr. John Whyte, edited MacEachen’s Gaelic Dictionary, a most useful work, and also with Mr. Whyte brought out some Gaelic school books. But, though his brain was active and his interest unabated, he no longer possessed the physical elasticity necessary to continue the strain to which he had subjected himself. He had overtaxed even his iron constitution, and now, when his school-day’s work was over, he contented himself with lighter things. Two or three subjects in particular occupied him specially for the last half-dozen years or more—the study of Personal Names, the Place-Names of Inverness-shire, and the annotation of his Dictionary. A specimen of his finest and most mature work in Place-Names appears in the current volume of the Gaelic Society’s Transaction. The same applies to his paper on Personal Names, which appeared in the fifth number of the Celtic Review. His other principal contribution to its pages was a review of my own Place-Names of Ross and Cromarty.

The pages occupied by the present notice had been reserved for a review—such as he alone could write—of Dr. E. Windisch’s great Táin Bó Cualnge.

As a supplement to the Dictionary, Dr. Macbain printed separately in vol. xxi. of the Inverness Gaelic Society’s Transactions a list extending to 20 pp. of ‘Further Gaelic Words and Etymologies.’ In a prefatory note, after referring to the very flattering reception which the Dictionary had met, he goes on to make some interesting and characteristic remarks on the criticisms it had evoked. ‘Nor did the work fail to meet with critics who acted on Goldsmith’s golden rule in the Citizen of the World—to ask of any comedy why it was not a tragedy, and of any tragedy why it was not a comedy. I was asked how I had not given derivative words—though for that matter most of the seven thousand words in the Dictionary are derivatives; such a question overlooked the character of the work. Manifest derivatives belong to ordinary dictionaries, not to an etymological one. This was clearly indicated in the preface. . . . Another criticism was unscientific in the extreme; I was found fault with for excluding Irish words! Why, it was the best service I could render to Celtic philology, to present a pure vocabulary of the Scottish dialect of Gaelic.’

Such is a brief and incomplete account of Macbain’s written work. But that is not all. No man could be more generous in helping others. Either by letter or by conversation, the stores of his knowledge and the wisdom of his counsel were open to all fellow-students. Of jealousy he was wholly free: his one aim was to add to the sum total of scientific knowledge, to enlarge the kingdom of facts. Sometimes his generosity was poorly rewarded; this, knowing human nature, he took philosophically.

Much might be said, something must be said, about the man himself. The following extract from a diary now before me speaks for itself. On New Year’s Day 1875, being then a student at the Grammar School of Old Aberdeen, he writes:—‘I think that I have now a good chance of yet appearing as an M.A. on equal terms in education with the other literary men of our day, a goal which has always been my ambition to arrive at, that I might have confidence to engage in discussing the topics which engross the attention of mankind. I dread to commit myself through ignorance, and ere I will appear (if ever I shall) in public, I will be backed up with a complete knowledge of the facts I speak on. This is high talking for a poor student in the second class of the Grammar School of Old Aberdeen.’ Nothing could express better the guiding principle from which he never swerved. He had the true scientific spirit in his respect for facts and in the pains he took, and insisted on others taking, to verify them. No statement of his is made at haphazard; he would delay his work until he was satisfied of the accuracy of every detail. This reverence for truth he had the knack of inspiring in others who came in touch with him. He had the insight of the philosopher into the significance of the facts he dealt with, and the consequent power to correlate and illumine them. Put shortly, his mind was in a high degree analytic and in nearly if not quite as high a degree synthetic No one who knew him well could fail to be impressed with the absolute independence as well as the power of his mind. He was an ideal seeker after truth. A severe critic of his own work, he was highly appreciative of the work of others. He was not lenient to error, especially if the error arose from want of verifying facts which ought to have been verified. Charlatans found to their cost that he could on occasion wield a grievous cudgel. But he was scrupulously fair in statement, and ready to recognise the good points even of a weakling. Full of much courtesy and nobility of heart, he was also a man of much humour of the quieter sort, a trait which appears in his writings but sparingly. His practical wisdom was well known and appreciated in the council of the Gaelic Society, in the Free Library Committee, of which he was long a useful member, and by the many friends and former pupils who sought him for advice. He had the power characteristic of great minds of getting at the essentials of a question, and of seeing things in true perspective.

It would be a mistake to regard Macbain as a Celtic scholar simply. It is probably not too much to say that he knew English literature and English philology as well as he knew Gaelic. A competent judge declared that of all the men he had met, Macbain had the best knowledge of English literature. I do not touch on his political views, which were strongly liberal, nor on other subjects on which he held clear and strong opinions. There were, indeed, few subjects of general interest which he had not considered with the same freshness and independence of thought which characterised all his work.

The extent and value of his work can perhaps be best appreciated by considering the condition in which Gaelic scholarship would now be without it. His researches have raised Gaelic philology to the highest scientific plane. Neither Welsh nor Irish has a philological dictionary; it is but recently that Victor Henry produced one of Breton, in the preface to which he acknowledges his great obligations to Macbain. He has made valuable contributions to Scottish history; he might, alas! have done much more had time been granted him. He laid the foundation of the study of Celtic Place-Names, and did much to reduce the study of Norse-Gaelic names to scientific accuracy. From him we know practically all that is known about the origin of our Highland personal names. Truly a great achievement for a man with scanty leisure, who is cut off before he has reached fifty-two.

And now he is gone, and Inverness is a less interesting place than it was. The sturdy, square figure, the massive head, the rugged, kindly face, the shrewd grey eyes twinkling under bushy brows are now but memories. We shall miss his sage counsel and his friendly clasp; we shall long sorrow for the loss of the light and leading that he alone could give in many departments. He was a great man, and he deserved well of Scotland. We shall not look upon his like again. A chuid de Phàras da!

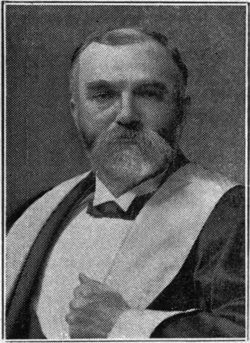

The excellent photograph of Dr. Macbain is reproduced by courteous permission of the proprietors of the Highland Times, Inverness.