The Chinese Empire. A General & Missionary Survey/Introduction

INTRODUCTION

By the Editor

The Chinese Empire, whether viewed from the standpoint of its extent of territory, the wealth of its resources, the antiquity and vitality of its teeming population, or in view of its past history and future prospects, cannot but command the most serious and thoughtful consideration of all who are interested in the welfare of the human race.

Year by year China has attracted increasing attention, and has commanded a larger place in the minds of men, no matter whether it be the missionary, commercial, or international questions which interest the observer. Few, if any, of the problems of human life to-day are of greater importance and of a more fascinating nature than those presented by the Chinese Empire. With the threatened dismemberment of the Empire but recently averted, with her integrity practically assured by the renewal of the Alliance between England and Japan, with a spirit of reform moving the country from east to west and north to south, the future of China portends great weal or woe to the rest of mankind.

For exactly one hundred years, from 1807 to 1907, Protestant Missions have been endeavouring to bring to bear upon the Chinese people the regenerating and ennobling influences of the Gospel, and it has been acknowledged by the Chinese themselves, as well as by the European and American residents, that the beneficent influence of the truth made known through the various evangelical, educational, and philanthropic channels has played no small part in producing those aspirations for better things which are so evident in China to-day. Without attempting, in detail, to summarise the geographical, historical, and missionary information of the following pages, as given by each writer under his own section, a short introduction to those articles is necessary.

The area of the Chinese Empire is to-day given as 4,277,170 square miles, which is considerably smaller than the Empire was in the prosperous days of Kienlung (A.D. 1737-1796); more than half a million square miles of territory having been taken from China by Russia alone since that date.

From the figures given in the footnote[1] it will be seen that the Chinese Empire comprises about one-twelfth of the total territory of the world, while it occupies nearly one-quarter of the whole continent of Asia, the largest of continents. It is considerably larger than Europe, and is nearly equal to half of the vast continent of North America, being much larger than either the United States or the Dominion of Canada taken separately. Twenty countries equal in size to France, or thirty-five countries equal in area to the British Isles, could be placed within the Chinese Empire, while more than one-third of these would be located within that portion known as China Proper.

For a traveller to encircle China he would need to journey a distance considerably greater than half the circumference of the world. Of this distance some 4000 miles would be coast-line, some 6000 miles would be bordering on Russian territory, another 4800 miles would touch British possessions, while of the remainder, some 400 miles would be contiguous to country under French rule and about 800 miles might be described as doubtful.

Vast as is the area of the Chinese Empire, there is naturally a greater interest attaching to its people than to the land itself. In the millions of this Empire the merchant sees one of the largest and most promising markets of the world; the financier recognises an almost limitless field for mining enterprise; the statesman and the soldier perceive political and military problems of the most stupendous magnitude; while the Christian, though not unmindful of other aspects, thinks more of the countless millions of men and women who are living and dying without that knowledge which is alone able to make them wise unto salvation.

The most recently accepted census of the population published by the Chinese Government gives the total population of the Empire as 426,000,000.[2] That so large a proportion of the human race should be located in one empire is an astonishing fact, and it is not to be wondered at that some persons have questioned the trustworthiness of these figures. It is certainly remarkable that about one-quarter of the world's population should be settled in a territory which is only one-twelfth of the whole; or, if reference be made to China Proper only, that one-quarter of the world's population should be crowded into a country which possesses not more than one-thirtieth of the inhabitable land of the globe.

Much as these facts may provoke a doubt in the mind of the student, the only possible data at present is that supplied by the Chinese Government, though other evidences can be adduced to show that these figures are not altogether incredible. The Rev. Arthur H. Smith has — by careful calculations in limited areas to be accepted as a unit of measurement for other districts which to all appearances are equally populated — proved that in some areas there is a population of 531 to the square mile, while in another area the population worked out at 2129 per square mile. Commenting on his own experiments, he has said: "For the plain of North China as a whole it is probable that it would be found more reasonable to estimate 300 persons to the square mile for the more sparsely settled regions, and from 1000 to 1500 for the more thickly settled regions."

Colonel Manifold, in a lecture before the Royal Geographical Society in 1903, expressed his belief that the population of the Chengtu plain was no less than 1700 to the square mile; and Consul W. J. Clennell, in China, No. 1, 1903, gives the population of Shanghai as "something like 160,000 to a square mile." When it is remembered that the population in London ranges up to 60,000 to the square mile, and that in the poorest parts of Liverpool it is nowhere above 100,000 per square mile, the density of population in some of the Chinese cities will be more easily appreciated.

It is more easy to speak of millions than to appreciate the significance of the word. It is less than one million days since Isaiah penned his prophecies, and less than one million hours since Morrison landed in Canton. The death-rate of China alone would in six months blot out London, or in a fortnight the British army, while one day would remove the entire population of Canterbury. This is not mere sentiment, but actual fact. Could we but realise the misery, the hopelessness, the fear and dread which encircle one death in the land where Christ is not known, we should surely be moved to greater efforts and to a more supreme consecration and willing self-denial that the true Light might shine upon those now sitting in darkness and in the shadow of death.

EARLY MISSIONS

Although the breviary of the Malabar Church and the Syrian Canon both record that St. Thomas preached the Gospel to the Chinese, and although Arnobius, the Christian apologist (A.D. 300) writes of the Christian deeds done in India and among the Seres (Chinese), the first certain date concerning early missions in China is connected with the work of the Nestorian Church. It is now generally accepted that the Nestorians made their entry into China as early as A.D. 505, and records exist stating that Nestorian monks brought the eggs of the silkworm from China to Constantinople in A.D. 551. The discovery, at Sian Fu in A.D. 1625, of the Nestorian tablet, places the question of Nestorian Missions in China beyond all doubt. This tablet, which was erected in A.D. 781, tells of the arrival of Nestorian missionaries at Sian Fu, the then capital of China, as early as A.D. 635, and gives some brief account of their work and teaching.

Although these early missionaries preached the Gospel and translated the Scriptures, of which translation, however, there is now no trace, their work was not of an abiding character. Partly through subsequent persecution on the part of the Chinese Government, partly through the rise of Mohammedanism and the power of the Arabs, who cut off their connection with the west, and probably because their Gospel was not a full Gospel, their work did not abide the test of time and the strain of adverse conditions. Nevertheless, traces of their work are to be found through many centuries.

In A.D. 845 the Emperor Wu Tsung, when condemning 4600 Buddhist monasteries to be destroyed, also ordered 300 foreign priests, whether of Tath-sin (the Roman Empire) or Muhura, "to return to secular life, to the end that the customs of the empire may be uniform."[3] The accounts of two Arab travellers of the ninth century (A.D. 851 and 878) also give eloquent evidence of the knowledge of the truth in China, Ebn Wahab and the Emperor holding an interesting dialogue about the facts and history of the Old and New Testaments. Again, Marco Polo in the thirteenth century, and the early Franciscan missionaries also, referred to the Nestorians and their work. In A.D. 1725 a Syrian manuscript, containing a large portion of the Old Testament and a collection of hymns, was discovered in the possession of a Chinese. This is thought to be one of the few relics of this early Church. Being, however, cut off from all intercourse with their mother Church by the rise of Mohammedanism, and lacking the vigour of a pure faith, their work has passed away leaving little trace behind.

First Roman Catholic Effort

The first and second efforts of the Roman Catholic Church to evangelise the Far East took place during periods of world-wide activity. While the fervour which was stirring Europe to engage in the Crusades was still burning, while Venice was manifesting her keen commercial activity,—and Marco Polo was a Venetian—and while the zeal of the great orders of St. Dominic and St. Francis of Assisi was at its height, the Church of Rome commenced what we may now call her first effort to evangelise the Far East by sending her messengers to the court of the great Mongol power. The peace of Europe had just been threatened by the terrible invasion of the hordes of Jenghis Khan, and in return the Church of Rome sent back to Jenghis Khan's successors their messengers of peace.

In A.D. 1246 John de Plano Carpini started upon his journey for the Far East, and in A.D. 1288 Pope Nicholas IV. despatched John de Monte Corvino upon what became the first settled Roman Catholic Mission in the court of Kublai Khan, the founder of the Yüen or Mongol dynasty in China. The missionary activity which existed in Europe at this time is revealed by Raymond Lull's advocation of the founding of a chair in the University of Paris for the study of the Tartar tongue, that "thus we may learn the language of the adversaries of God; and that our learned men, by preaching to them and teaching them, may by the sword of the Truth overcome their falsehood and restore to God a people as an acceptable offering, and may convert our foes and His to friends."

However much one may feel that John de Monte Corvino's teaching as a messenger of Rome may differ from the Protestant faith of to-day, there can be no question that he was in spirit a true missionary. Opposed by the Nestorians, cut off for twelve long years from any communication with Europe, he did what the Roman Catholic Church are not accustomed to do to-day, he translated the whole of the New Testament and the Psalter into the language of the Tartars among whom he dwelt, and publicly taught the law of Christ. His two extant letters are pathetic records of his labours. Grey-headed through his toils and tribulations long before his time, he yet cheerfully endured the hardships of his mission, and survived until the ripe age of seventy-eight, having been appointed Archbishop of China in 1307. It was at the time of this appointment that Clement V. sent seven assistants to help him, and after his death various successors were appointed; but the sway of the Mongol dynasty was not for long, and with its fall, and with the rise of the Ming dynasty which followed, Christianity was for a time swept out of China.

One of the grandest opportunities that the Church of Christ has ever had presented to it, and it must be remembered this was before the rise of Protestantism, is connected with the lifetime of Kublai Khan mentioned above. There are letters still extant, preserved in the French archives, relating the remarkable fact that Kublai Khan actually requested the Pope to send one hundred missionaries to his country "to prove by force of argument, to idolaters and other kinds of folk, that the law of Christ was best, and that all other religions were false and naught; and that if they would prove this, he and all under him would become Christians and the Church's liegemen." "What might have been" is a question that cannot but rise in the hearts of those who read this extract. The death of the Pope, however, and faction among the cardinals, with the subsequent failure of the two missionaries sent — they turned back because of the hardships of the way—lost to Asia an opportunity such as the Church has seldom had.

Second Roman Catholic Effort

Period of Growth, 1579-1722; Period of Decline, 1722-1809

This second period of Roman Catholic effort synchronises with the Renaissance of the sixteenth century, with the rise of Protestantism, and is connected with Vasco da Gama's enterprise in doubling the Cape and taking possession of Malacca, for' from this base Xavier carried on his labours in the Ear East.

While in Europe the Reformation was becoming an increasing power, the Church of Rome commenced its counter-reformation in a strong missionary propaganda. The navigation of the East being under the control of Portugal and Spain, the Protestant Church was excluded from missionary activity even had it so desired. In the same year as England threw off the papal yoke, the order of the Jesuits, of which Xavier was one of the original members, was formed. The story of his labours in India, of his mission to Japan, and his death off the coast of China, are too well known to need repetition here. His inspiring zeal and his burning love to Christ, together with his failings and errors as a missionary, have been revealed through his translated letters, edited by the late Henry Venn, Honorary Secretary of the Church Missionary Society.

In 1560 the Portuguese took Macao, and Valignani, Superintendent of the Jesuits' Missions to the East, settled there. His are the words so frequently but wrongly ascribed to Xavier: "Oh rock, rock, rock, when wilt thou open to my Lord!" The Fathers Rogers and Ricci were selected by Valignani as pioneers to China, but Rogers shortly returned to Rome. In 1582 Ricci succeeded in gaining a foothold on the mainland at Shaoking, the residence of the Governor, and by a system which subordinated the Gospel to expediency, he slowly worked his way to Peking, which city he reached in 1601, just twenty-one years after landing in Macao. During the intervening period he had settled Missions at Nanchang Fu, Suchow Fu, and Nanking Fu. At his death in 1610 an imperial edict ordered the erection of a monument to his memory.

Of his ability and that of his colleagues there can be no question, but of his methods it must be said they merit the criticism and censure they have received. By 1637 he with his colleagues had published no fewer than three hundred and forty treatises upon religion, philosophy, and mathematics, and among his most noted converts must be mentioned Paul Sü and his widowed daughter Candida. But for Paul Sü's defence, the Roman Catholic Missions in subsequent years would have suffered even more severely than they did.

In 1631 the Dominicans and Franciscans began to arrive in China, but were not welcomed by the Jesuits, with whom a bitter controversy arose. With the break-up of the Ming dynasty and the rise of the present Manchu power, all parties more or less suffered, though Schaal, the able and distinguished successor of Ricci, was, through Paul Sü's recommendation, placed in a position of honour. Schaal, however, eventually died of grief, Verbiest and others were imprisoned, while twenty-one Jesuits were banished from the country. This was during the minority of the famous Emperor Kang-hsi, under whom subsequently the Roman Catholics enjoyed great favour. It was under his enlightened rule that the Jesuits prepared their careful survey of the Empire and reformed the calendar, Verbiest causing no small chagrin to the native astronomers by his remark, "It is not within my power to make the heavens agree with your diagrams!"

Although during the earlier portion of Kang-hsi's reign of sixty years he had heaped favours upon the Jesuits, had built a magnificent church for them in Pekin, and written with his own hand an honorific tablet in their favour, the strife between the followers of Loyola, Dominic, and Francis as to the word wherewith to translate "God," and concerning the true significance of ancestral worship, etc., led eventually to an impasse between the Emperor and the Pope. On the one hand, the Pope required all missionaries proceeding to China to sign a formula promising obedience to the orders of the Vatican on these points, while the Emperor on his part forbade any missionary to remain in the country unless willing to accept his interpretation.

Bulls almost contradictory in their instructions were issued by various popes, and special legates were despatched to China—one of whom died there in prison, without the attainment of a satisfactory settlement. In some respects the controversy may be said to have largely arisen through the unworthy compromises and ambition for imperial favour which characterised the Jesuits' policy. With the death of Kang-hsi in 1722 the period of favour passed away and one of decline set in. An edict was almost immediately issued (1724) by Yong-ching, Kang-hsi's successor, closing all provincial churches and limiting the residence of missionaries to Peking and Canton; while in 1744 the next Emperor, Kien-lung, whose reign lasted nearly sixty years, and under whom the Empire attained its zenith both in power and extent, encouraged a general persecution throughout the country, hundreds of Chinese Christians and some ten Europeans being put to death.

The suppression of the Jesuits by Clement XIV. in 1773, the overbearing attitude of the Portuguese traders at Macao, and the haughty conduct of the East India Company at Canton, and finally the overthrow of the papacy by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1809, are important events which affected and mark the rapid decline of Roman Catholic Missions in China, during the latter portion of the eighteenth and the opening years of the nineteenth century.

While many of the methods employed by the Roman Catholic missionaries, and especially by the Jesuits, cannot but be severely criticised, there is no question as to their devotion, their ability and influence, and their willingness to suffer hardship. To Roman Catholic missionaries Europe was indebted for almost all that was known about China, and Dr. Morrison received no small assistance through their early translations and literary work. Their methods may be a warning, but their zeal should certainly be an inspiration and reproof.

The order of the Jesuits was re-established in 1822, from which time the Roman Catholics have continued to push forward their work in China.

PROTESTANT MISSIONS

Period of Preparation, 1807–1842

Just one hundred years ago, in 1807, when the guns of Napoleon Bonaparte and the tramp of his guards were shaking the thrones of Europe to their very foundations, just eight years before the Battle of Waterloo gave to the troubled peoples any sense of security. Dr. Morrison sailed for the distant and then little known Empire of China. The vigour and enterprise both of Church and State in those days are a cause of ceaseless encouragement; and how far the faith and loyalty[4] of God's people, who in the darkest hours of national life dared and attempted great things for God, moved the heart and arm of Him who is the great Disposer of kings and peoples to give the victory to British arms, only eternity will fully show.

Dr. Morrison landed in Canton in the autumn of 1807, having previously prepared himself for his future work, so far as that was possible, by some preliminary study of the Chinese language, by the transcribing of a Chinese manuscript of part of the New Testament found in the British Museum (see p. 379), and by making a copy of a Chinese and Latin dictionary. Confronted by a closed land and mountains of difficulty, he, to quote the words of his subsequent colleague. Dr. Milne, with "the patience that refuses to be conquered, the diligence that never tires, the caution that always trembles, and the studious habit that spontaneously seeks retirement," laid the foundations of all subsequent missionary work.

From 1807 to 1834—the same year that the East India Company's charter ceased—he laboured on practically alone, for Milne, who reached China in 1813 and died in 1822, was not allowed to live at Canton. Shortly before his death, however, he was cheered by the arrival of three workers from America, Bridgman[5] and Abeel, who reached Canton in 1830—though Abeel shortly afterwards left for Siam—and Wells-Williams,[5] who reached Macao the year before Morrison died. Thus for twenty-seven years, with the exception of his furlough in 1824, he laboured on at his great task, in loneliness, often in sickness, and amid almost overwhelming discouragements. The love and courage of the two women—for he was twice married—who shared his toils and sorrows must not be forgotten. Among his trials must be mentioned the long times of painful separation from wife and children, once for six unbroken years.

It is true that the London Missionary Society had sent out more than ten men whose aim was the evangelisation

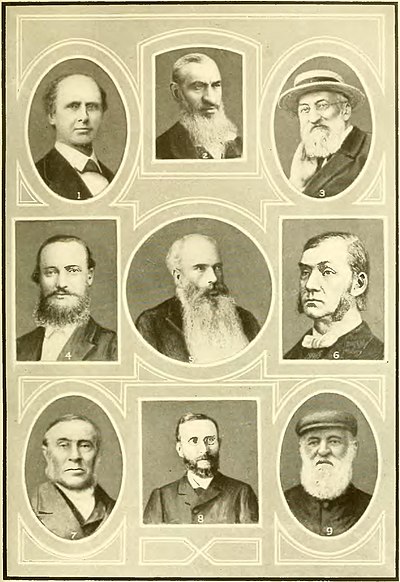

| GROUP I. | ||

| 1. Bishop Burdon. | 2. Rev. W. H. Medhurst. | 3. Dr. Lockhart. |

| 4. Dr. Peter Parker. | 5. Bishop George Smith. | 6. Rev. F. Genähr. |

| 7. Rev. Dr. Legge. | 8. Bishop Boone, Sen. | 9. Rev. Wells Williams. |

For short Biographical outlines, see pages 436-7.

of China, but these were obliged to remain in what was called the Ultra-Ganges Mission; so that, "in the face of almost every discouragement short of violent expulsion from the country, he had accomplished, almost single-handed, three great tasks—the Chinese Dictionary, the establishment of the Anglo-Chinese College at Malacca, and the translation of the Holy Scriptures into the book-language of China." Twice his font of type was destroyed and his press had to be removed to Malacca, and in addition to this he had to face the adverse edicts of the Chinese Government, forbidding the circulation of foreign books and preaching of the foreign doctrine. The friendly attitude of some of the American merchants, however, was a silver lining to the dark cloud. Through one of these, Mr. Olyphant, some of the American Societies became deeply interested in China, Mr. Olyphant subsequently placing his ships at the disposal of these Societies for the free transport of their missionaries to the field.

The L.M.S., while seeking to enter China from the south, also commenced an effort to reach the tribes of Mongolia on the north, Messrs. Stallybrass and Swan commencing their work on the borders of Lake Baikal in 1818. This Mission was closed by the Holy Synod of the Russian Government in 1840, but not before the greater part of the Bible had been translated into Mongolian.

The remarkable journeys of Gutzlaff also fall within the period of Morrison's life. During the five years 1831-35, Karl Gutzlaff, connected with the Netherlands Missionary Society, made seven journeys along the coasts of Siam and China, reaching Tientsin in 1831. The greatest interest was aroused both in England and America, among missionary, commercial, and political circles, and in 1835 the L.M.S. requested Dr. Medhurst to attempt similar journeys. Dr. Medhurst did so, and reached Shantung in company with the Kev. E. Stevens. Although events proved that China was not yet as accessible as had been anticipated, Gutzlaff was nevertheless used of God to kindle a flame of enthusiasm in the hearts of not a few. Indirectly his zeal led to the formation of the Chinese Evangelisation Society, which sent out Mr. Hudson Taylor, while his visit to Herrnhut resulted in the Moravian Mission to Tibet commenced in 1853, although Mongolia had been the goal intended. His industry was enormous, and, though not always reliable, his publications, according to Wells-Williams, numbered no fewer than eighty-five in the Chinese, Japanese, Dutch, German, English, Siamese, Cochin-Chinese, and Latin languages.

In 1834 the East India Company's charter ceased and the trade in the Far East was thrown open to all. Open competition immediately led to an increase in the amount of opium carried to China, to the not unnatural consternation of the Chinese Government. At the same time the change in arrangements was not understood. Having previously only had to negotiate with merchants, they refused to treat with Lord Napier, the newly-appointed Superintendent, as an official of equal rank with the Viceroy of Canton. Determined, on the one hand, to stop the trade, and equally, though foolishly, determined, on the other hand, not to deal with the "foreign barbarian" on the basis of equality, an impasse soon arose which needed only time to develop into war. Trade was stopped, smuggling increased, and finally Commissioner Lin was specially appointed by the Chinese Government to crush the opium trade.

Lin's determined attitude, his blockade of the factories and the burning of 20,283 chests of opium valued at twenty millions of dollars, cannot be criticised by any one who admires patriotism and zeal for national purity. In the matter of the opium, China was in the right and England in the wrong, but in many other matters China's attitude cannot be excused nor England's annoyance altogether condemned. England was not unjustly out of patience with Chinese diplomacy, though she was unjustly determined to force her trade, and more especially her opium traffic.

The war that followed was brought to a close by the cession of Hongkong to the British in 1841, and by the signing of the Treaty of Nanking in 1842. By this treaty the live ports of Canton, Amoy, Shanghai, Ningpo, and Fuchow were thrown open to trade, Hongkong was assured to the British, and $21,000,000 was determined as the sum to be paid the victors for indemnity. Through the subsequent treaties of 1844 with the United States of America and that of 1845 with Trance, the toleration of Christianity was obtained, and the persecuting edicts of 1724 and later, rescinded.

Before proceeding to review the new period of missionary enterprise ushered in by the Treaty of Nanking, it is necessary to record that medical missions to the Chinese had already made a good beginning. In 1834, the year that Morrison died. Dr. Peter Parker of the American Board landed in Canton, and during the following year opened the first missionary hospital in China. Previous to this Morrison himself, with two doctors connected with the East India Company, had done something in the way of dispensary work, but these efforts had ceased in 1832. Dr. Cumming, an independent and self-supporting worker, had commenced work at Amoy almost as soon as that port was opened in 1842; while Dr. Lockhart, who had opened a hospital at Tinghai in Chusan in 1841—when that island was occupied by the British troops—moved to Shanghai in 1844. Another hospital was opened at Canton by Dr. Hobson in 1846. Thus was begun that branch of Mission work which was to be so much used of God in after years to break down the opposition and distrust of the Chinese.

In 1834 a Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge in China was inaugurated, and in 1835 the Morrison Educational Society was founded. During the whole of this period, from 1807 to 1842, fifty-seven workers had either in China or in the Straits sought to advance the Kingdom of God among the Chinese. Of these fifty-seven persons, ten had died before the period closed, while fifteen had retired, leaving thirty-two still living in 1842. These fifty-seven workers had been connected with the following eight Societies: the London Missionary Society, the Nether- lands Mission, the American Board, the American Baptists, the American Episcopalians, the Church Missionary Society, the American Presbyterians, and the Morrison Educational Society.

Period of the Ports, 1842–1860

With the signing of the Treaty of Nanking and the opening of the five treaty ports, missionary work entered upon an entirely new era. At the time of Morrison's death there had been only two missionaries residing in China Proper, Messrs. Bridgman and Wells -Williams, both of the American Board. Dr. Parker and the Eev. Edwin Stevens both reached Canton in 1834, though the latter died in 1837.

With the opening of the treaty ports there was an immediate move forward. Messrs. Roberts and Shuck of the American Baptist Mission appear to have been the first to settle at Hongkong, moving there in 1842. In the following year the London Missionary Society transferred its printing press and its Anglo-Chinese College to that colony. Dr. Legge, who had been in Malacca since 1839, being its Principal. For the next thirty-four years, until his appointment as Professor of Chinese at Oxford, Dr. Legge continued his invaluable labours, placing the whole world, and the missionary body especially, under a lasting obligation to him for his translations and commentaries on the Chinese classics. Among his colleagues in the L.M.S. at Hongkong must be mentioned Drs. Chalmers and Hobson.

Among the other Societies represented at Hongkong during this period were the Church Missionary Society temporarily;[6] the Basel Missionary Society, which commenced work on the island in 1847; and the Rhenish

| 1. Rev. M. T. Yates. | 2. Rev. A. Williamson. | 3. Rev. C. P. Piton. |

| 4. Rev. H. Z. Kloekers. | 5. Rev. Dr. Faber. | 6. Rev. R. Lechler. |

| 7. Rev. Ed. Pagell. | 8. Rev. M. Schaub. | 9. Rev. A. W. Heyde. |

In Canton the work grew round such men as the Rev. R. H. Graves of the American Baptists, South, a worker who has recently celebrated his Jubilee of missionary service in China; while the Rev. I. J. Roberts, subsequently famous as the one to whom the leader of the Taiping Rebellion made application for baptism, had moved from Hongkong to this city.

The work at Amoy was founded by Abeel and Boone in 1842, and among the names permanently associated with that centre are William Burns and Carstairs Douglas of the English Presbyterian Mission. Fuchow was opened by the Rev. Stephens Johnson of the American Board in 1846, after thirteen years' work at Bangkok, he being joined by the Rev. J. Doolittle of the same Society. The American Methodist Episcopalians and the Church Missionary Society followed, the latter Mission being severely tested by eleven years of hard toil before any visible results were seen. With this centre also is connected the first effort of the Church in Sweden to assist in the evangelisation of China. The Missionary Society of Lund sent out two men; but before work had been commenced, one had been killed by pirates and the other so severely wounded as to be invalided for life.

Going northward to Ningpo, we find the work there carried on by several Societies. The American Baptists were represented by Drs. D. J. Macgowan, E. C. Lord, and J. Goddard; the American Presbyterians with a strong work under Dr. D. B. M'Cartee, Dr. W. A. P. Martin, and others; the English Baptists with their first China Mission opened by T. H. Hudson ; and the Church Missionary Society represented by Cobbold, Russell, Gough, and G. E. Moule. Both Russell and G. E. Moule were subsequently consecrated Bishops. The remarkable work among Chinese girls carried on by Miss Aldersey, who had left England as early as 1837 for Java, whence she removed to Ningpo, must not be forgotten; nor the lamented Mr. Lowrie, who was murdered by pirates at sea.

At Shanghai some nine or ten Societies commenced work, the details of which would weary the general reader. Among the outstanding men at that centre, mention should be made of Drs. Medhurst, Lockhart, Muirhead, Edkins, Griffith John, and Mr. Wylie, all of the L.M.S.; Bishop Boone, the Rev., afterwards Bishop, Schereschewsky of the American Episcopalian; Dr. Bridgman of the American Board, who had removed there from Canton; and the Rev. J. Hudson Taylor of the Chinese Evangelisation Society, who removed to Ningpo in 1856.

To summarise the period. During the eighteen years between the Treaty of Nanking and the Peking Convention, some seventeen Societies had commenced work in China, having, with the other Societies already on the field, sent out some 160 to 170 workers, not counting wives. Of these, seventy had either died or retired during the period, while of the seventeen Societies mentioned, at least five of them have no work in China to-day.

The two outstanding events which materially affected the missionary work of this period were the outbreak of the Taiping Rebellion and the second war which preceded the Treaty of Tientsin.

Hong Siu-ts'üen, with whom the Taiping Rebellion originated, was born in 1813, the year that Milne reached Canton. At the age of twenty he received a tract from Liang A-fah, Dr. Morrison's convert and helper. The tract was, however, neglected for some ten years, during which time his annoyance at repeated failures to obtain his degree greatly aggravated an illness which assumed the form of cataleptic fits and visions. Connecting these visions with what he subsequently read in the tract, he started upon a crusade against idolatry and the reigning dynasty. An attempt to arrest him resulted in his finally taking up arms against the throne and the proclaiming of himself as the "Heavenly King,"

Inspired in its beginnings with much that was good, such as the condemnation of opium-smoking, the observance of the Sabbath, the circulation of the Scriptures—these being specially bound with the Taiping arms emblazoned on the cover—it gradually degenerated into a cruel and terrible rebellion which devastated the fairest of China's provinces and slew millions of human lives. The rebellion was not quelled until 1864, wheu the city of Nanking fell before General Gordon, the rising having commenced in 1850. With the various opinions as to the good and evil connected with this movement there is not space to deal here. Suffice it to say that the British and Foreign Bible Society in 1853 decided to celebrate its Jubilee by the printing of one million New Testaments in Chinese, the Christian public at home, in common with many of the missionaries on the field, hoping that the movement might result in a general acceptance of Christianity on the part of the Chinese.

Meanwhile, in the midst of these troubles, England's second war with China broke out over the lorcha Arrow incident. This boat, engaged in smuggling opium, was flying the British flag, but without authorisation for so doing. The Chinese Government not unnaturally seized the boat (Oct. 1856), knowing her true nature, while the British demanded immediate satisfaction for what was regarded by them as an insult to the British flag. The war which followed lasted, with an unsatisfactory peace of one year, from 1856—when Canton was bombarded—until 1860, when the 1858 treaty of Tientsin was ratified at Peking.

From 1858 to 1860 no fewer than nine treaties were signed between China on the one hand, and Britain, the United States, France, and Russia on the other, while one with Prussia was signed during the following year. By these treaties Peking was opened to the residence of Foreign Ministers, and, if the whole list as it appears in Article VI. of the Prussian Treaty[7] be followed, the following ports were declared opened to trade: Canton, Swatow, Amoy, Foochow, Ningpo, Shanghai, Chefoo, Tientsin, Niuchuang, Chinkiang, Kiukiang, Hankow, Kiungchow (Hainan), and Taiwan and Tamsui in Formosa. Five of these had, of course, been opened by the Nanking Treaty of 1842.

Among the important items of the British Treaty must be mentioned the Tariff revision, which was acknowledged as part and parcel of the Treaty. Rule V. of this Tariff reads: "The restrictions affecting trade in opium, etc., are relaxed, under the following conditions: Opium shall henceforth pay 30 taels per picul import duty." This was to prevent the Chinese excluding the trade by the imposition of a more heavy duty. Comment is not needed.

In addition to the opening of the ports mentioned above, the right to travel, with passport, throughout the eighteen provinces was granted, the protection of foreigners and Chinese propagating or adopting Christianity was promised, while the Chinese translation of the French Treaty gave special permission to French missionaries " to rent and purchase land in the provinces and to erect buildings thereon at pleasure." Although the French text, which was the final authority, did not contain this clause—it having been surreptitiously inserted by one of the French priests into the Chinese text, an action not unnaturally severely criticised—the Chinese never raised any serious objection and were guided by their own translation.

Period of Penetration, 1860-1877

. Rev. Josiah Cox.

4. Rev. Wm. Burns.

7. Rev. Geo. Pieucy.

GROUP III.

. Rev. Wm. Muikhead.

.^). Rev. J. GiLMOUR.

. Rev. Roderick Macdoxald, M.D.

For short Bioyraphical ovflines, see puyes 439-40.

. Mu. A. WvLiE.

t). Rev. David Hill.

. Rev. Joseph Edkins, D.D.

To face page 21. at Tientsin in 1858 and its ratification at Peking in 1860, the British squadron proceeded up the river Yangtse, and Dr. Muirhead of the L.M.S. was allowed as a special favour to accompany the expedition. In consequence of his report, Griffith John and R. Wilson were designated to Hankow by the L.M.S., which important city they reached in 1861, soon after it had been opened as one of the new ports.

In 1862 Josiah Cox, of the Wesleyan Missionary Society, reached the same strategic centre, being joined shortly afterwards by Dr. Porter Smith, the first medical missionary to Central China, in 1864, and by David Hill in 1865. In 1864 Griffith John had the joy of baptizing his first converts at Hankow, and in the same year the first Chinese clergyman connected with the C.M.S. was ordained at Shanghai by Bishop Smith.

An advance was also made towards the north of China: Dr. Edkins of the L.M.S. settled at Tientsin in 1861, and Dr. Lockhart of the same Society was permitted to reside at Peking as medical adviser to the Legation. Dr. Edkins baptized the first converts at Peking in 1862, and settled there the following year, leaving the work at Tientsin in the care of Jonathan Lees. In 1864 Dr. Dudgeon succeeded Dr. Lockhart. The Methodist New Connexion commenced its China Mission in 1860, and early stationed its two workers, the Revs. J. Innocent and W. N. Hall, at Tientsin, out-station work being opened by this Society in Shantung in 1866.

In 1862 the C.M.S. commenced its direct Mission work both at Hongkong and in Peking, though Bishop Smith of Hongkong had previously been a C.M.S. man. The Rev. J. S. Burdon (afterwards Bishop) was allowed to remain at Peking as quasi chaplain to the British Embassy, where he was joined by W. H. Collins in 1863, when the restrictions against residence in that city were removed. Tengchow, some 55 miles north-west of Chefoo, was opened by the American Presbyterians, North, in 1861, the same Society commencing its work in Peking in 1863, by the transfer of Dr. W. A. P. Martin to that centre.

In the autumn of 1865, the Rev. G. E. Moule (afterwards Bishop Moule), with his family, moved to Hangchow in Chekiang. This was an important occasion, for it was the first definite case of inland residence at other than a Treaty Port, though the settlement of the American Presbyterians, as mentioned above, at Tengchow on the coast, some 55 miles from the nearest Treaty Port, must not be overlooked. The American Presbyterians and American Baptists soon followed to Hangchow, and in November 1866 Mr. Hudson Taylor made that city the first headquarters of the newly-formed China Inland Mission. It should also be mentioned that the United Methodist Free Church commenced its work in Ningpo in 1864.

Although great opportunities for the evangelisation of China were presented to the Christian Church by the signing of the Tientsin Treaty, unfortunately the Civil War in America seriously crippled the Missionary Societies of that country, and a spirit of religious indifference was no less seriously affecting the Churches of Great Britain. In 1860, when the Peking Convention was signed, the total number of missionaries in China is estimated to have been about 115; while in March 1865, when the China Inland Mission was projected, the total was only 112.[8] When the year 1866 dawned, there were in all only 15 Central Mission Stations, which were all at open ports, with the exception of Tengchow, which had been opened by the American Presbyterians in 1861; Kalgan, on the Mongolian frontier, which had been opened by the American Board in 1865; and Hangchow, which had been opened by the present Bishop G. E. Moule in 1865. These stations were all located in 7 provinces (including Formosa), all coast provinces, with the exception of Hupeh, in which Hankow is situated.

GROUP IV.

1. Rev. J. Macintyre. 4. Rev. W. N. Hall. 7. Rev. J. Ross.

2. Dr. J. M. Hunter. 5. Rev. J. Innocent. 8. Rev. H. Blodget.

3. Rev. Carstairs Douglas. 6. Rev. .J. L. Nevius. 9. Rev. H. Waddell.

For short Biographical outlines, see pages 440-1. Before we pass to the developments of the later 'sixties, it should be mentioned that in 1863 the S.P.G. sent out two men to China, but these only remained on the field for a few months, the permanent work of that Society being commenced at a later date. In 1864 Bishop Smith of Hongkong, after fifteen years of service, resigned this office, and the Kev. C. R Alford was consecrated Bishop of Victoria, while W. A. Eussell was appointed as C.M.S. Secretary for China. Bishop Alford threw himself heartily into the work of the C.M.S., visiting all their stations on the China coast, and travelling up the river Yangtse. So great was his zeal for the evangelisation of China, that he even proposed the founding of a new Society for that special purpose. The proposal, however, was not favoured at home.

The express object which lay behind the formation of the C.I.M. was the occupation of Inland China, there being at that time eleven inland provinces without any Protestant missionary. In 1866 two inland stations were opened in the province of Chekiang, by J. W. Stevenson, who had preceded the Lammermuir party. Three more inland stations in the same province were opened in 1867, and the city of Nankin, capital of Kiangsu, was occupied by Mr. Duncan in September of the following year.

Kiangsi was the first of the eleven "unoccupied provinces" to be opened to the Gospel, and this was by the American Methodist Episcopalian Mission, which commenced work at Kiukiang in 1868, the C.I.M. following in 1869. Anhwei, another of the "unoccupied provinces," was opened in January 1869 by the C.I.M., the cities of Chinkiang and Yangchow in Kiangsu having been opened by the same Mission in 1868. It was at this latter city that the terrible riot of 1868 took place.[9]

Meanwhile missionary work had been commenced in Manchuria, Dr. Williamson, as agent for the National Bible Society of Scotland, visiting Newchwang in 1866,[10] while William Burns settled there in 1867, though he died the following year. In 1869 the Irish Presbyterian Church opened its Mission in Manchuria by the appointing of Dr. J. M. Hunter and the Rev. H. Waddell; the United Presbyterian Church of Scotland (now the United Free Church) followed in 1872 by appointing the Rev. John Ross to that field, with which his name is now so familiar.

It was in 1870 that the L.M.S. commenced its second effort for the evangelisation of Mongolia, the first, as has been mentioned above, being closed by the Russian Government in 1840. This second effort is connected with the ever-to-be-remembered self-sacrificing labours of James Gilmour, who left Peking in 1870 to commence his twenty-one years of lonely and faithful toil for that land of his adoption. Gilmour's departure from Peking was hastened by the terrible news of the Tientsin massacre. Fearing that complications might arise which would hinder his undertaking, he by faith dared the possibility of having his line of communication cut, and "went out, not knowing whither he went."

The dreadful Tientsin massacre horrified the civilised world. The French Consul, several French missionaries, including nine Sisters of Mercy, together with some Roman Catholic converts, were at that time brutally killed. The time was one of considerable unrest, and even at Shanghai the foreign residents, with ships of war and more than five hundred volunteers, scarcely slept for fear of attack. Fresh criticism broke out at home against the missionaries, but Sir Thomas Wade and Earl Granville nobly stood by the missionary cause. As for France, the sudden outbreak of the Franco-German War prevented her bringing that strong pressure to bear upon China which she had at first threatened.

GROUP V. . Rev. Dr. Griffith John. 2. Rev. R. H. Graves. . BiSHOP G. E. Moui.E. 5. Bishop Schereschewsky. . Rev. J. L. Maxwell, M.D. 8. Dr. J. G. Kerr. . Bishop Russell. . Rev. Dr. W. A. P. Martin. . Bishop Hoare. For short Biographical outlines, see pages 441-2. To face page 25. Among the most important events which transpired between 1870 and 1875 should be mentioned the settlement of the long-delayed question of a Missionary Bishopric in connection with the C.M.S. This was accomplished by the consecration of Bishop Russell as Bishop for North China, and the regretted resignation of Bishop Alford; J. S. Burdon being consecrated as Bishop of Victoria in 1874. In 1871 the Canadian Presbyterians commenced their work on the Island of Formosa; and in 1874 the S.P.G. definitely commenced its China Mission by the appointment of two men to that field, one of whom is the present Bishop C. P. Scott. It was also in 1874 that the C.I.M. opened its station at Wuchang as a base for its advance into the interior. The same Mission also opened Bhamo in Burmah in 1875, with the hope that it might soon be possible to enter China from the west. It was also during the same year that the C.I.M. commenced its itinerations in what were to prove two of the most difficult provinces to be opened to the Gospel, the provinces of Honan and Hunan.

During this period an important advance was made in the intercourse of foreign nations with China, Ambassadors of the various powers being allowed audience with the Emperor Tong-chï, who had just attained his majority, without performing the usual Chinese prostrations. The missionaries had also been considerably perplexed by the difficult and vexed controversy over the terms to be used for God and Holy Spirit, concerning which subject more will be found in the chapter entitled "The Bible in the Chinese Empire."

With the year 1875 Missions in China entered upon a new and wider sphere. The murder of Mr. R. A. Margary, an English Consular Official who had been sent across China from east to west to escort an exploring party under Colonel H. Brown from Burmah into China, led to the relations between England and China being strained to their utmost. After more than eighteen months of diplomatic negotiations, with an ever-increasing tension, the nations were brought to the verge of war. Sir Thomas Wade hauled down the British flag and left Peking. The Chinese Government finding they had gone too far, despatched Li Hung-chang as their special Commissioner to overtake him at Chefoo, when the Chefoo Convention[11] of 1876 was signed.

Although the Tientsin Treaty of 1858 had, in the letter, given considerable facilities for missionary operations in the interior, these had been in large measure inoperative. The Chefoo Convention, however, in addition to giving force to privileges already granted, gave special facilities for travel, and made special arrangements whereby for two years officers might be sent by the British Minister to see that proclamations connected with the "Margary Settlement" were posted throughout the provinces.

In a remarkable way God had provided for the facilities granted by the Chefoo Convention being utilised for the evangelisation of China. Some two years previously, Mr. Hudson Taylor had been led to put forth an appeal for prayer that God would give a band of eighteen men for work in the then nine still unoccupied provinces. These men were given, and when the Convention was signed they were all in China, ready to take advantage of the unforeseen though prayed for openings. Mr. Taylor himself arrived just as the Convention was signed, and at once inaugurated a series of wide and systematic itinerations with the object of preparing the way for future and more settled work. That the opportunity was rapidly seized is proved by the fact that before the year closed—and the Convention had only been signed in September—Shansi, Shensi, and Kansu had been entered, while during the following year Szechwan and Yunnan had been traversed, the capital of Kweichow occupied, and Kwangsi visited.

During 1877 Mr. J. McCarthy accomplished his remarkable walk across China, an account of which was published

GROUP VI. 1. Rev. H. L. Mackenzie. 4. Rev. R. P. Laughton. 7. Rev. J. M'Carthy.

2. Dr. J. Cameron. 5. Rev. J. W. Stevenson. 8. Mr. James Meadows.

3. Dr. R. H. A. Schofield. 6. Rev. W. McGregor. 9. Mr. Adam Dorward.

For short Biographical outlines, see pages 443-4.

Both McCarthy and Cameron in their journeys crossed from China into Burmah, but were forbidden by the British authorities to recross the frontier, and J. W. Stevenson and H. Soltau had to wait for four years before they obtained permission to enter China from the west.[13] These journeys were only the beginnings of a more thorough survey of the unoccupied and less occupied parts of China. As many of these widespread itinerations were severely criticised at the time, it may perhaps be allowable to quote the opinion of so competent an authority as Mr. Eugene Stock. Writing of this period in the History of the Church Missionary Society, he says: "The work, in fact, only professed to be preparatory, and in that sense after years showed that its success was unmistakable. Gradually, but after a considerable time, not only the C.I.M. but many other Societies—the C.M.S. for one—established regular stations in the remoter provinces; and of all these Missions, the C.I.M. men were the courageous forerunners."

If it be remembered that this, the real opening of the interior of China, took place only a generation ago, it will be recognised what an immense advance has since been made. In addition to the above-mentioned itinerations, several long and important journeys had been made by members of other Missions, which must not be overlooked. The most remarkable of these were the following:——

1864. Dr. Williamson, to Eastern Mongolia.

1865. Mr. Bagley, to "remote provinces."

1866. Dr. Williamson and Rev. J. Lees, to Shensi, through Shansi, returning viâ Honan.

1867. Mr. Johnson, of B. and F.B.S., to Honan.

1868. Mr. Wylie and Dr. John, of L.M.S., to Szechwan and through Shensi.

1868. Mr. Oxenham, from Peking to Hankow, through Honan.

1867-70. Mr. Wellman, of B. and F.B.S., in Shansi.

1870-72. Mr. Mollman, of B. and F.B.S., in Shansi.

While these widespread itinerations were taking place, the first general Missionary Conference was held at Shanghai. At that gathering it was estimated that the total number of men who had joined the Protestant Missions to the Chinese up to 1876 was 484. The total number of workers, men and women, in the field in 1877 was 473. Of these, 228 were attached to 15 British Societies, 212 were connected with 12 American Societies, while 26 represented 2 Continental Missions, and 7 were unconnected. The total number of converts was 13,035.

The Period of Progress, Persecution, and Prosperity, 1878-1907

The wider openings afforded by the Chefoo Convention and the interest aroused in the Home Churches by the Conference of 1877, together with other causes, led to a noticeable advance in the occupation of China for Christ. Only four new Societies entered upon work in China during the 'seventies. These Societies were: the Canadian Presbyterian, which commenced its work in Formosa in 1871, though it did not open up work on the mainland until 1888; the S.P.G. in 1874; the American Bible Society in 1876; and the Church of Scotland in 1878. In addition to many Tract and Educational Societies formed in China about the time of the 1877 Conference and afterwards, there were no fewer than thirteen new Societies which entered upon work in China during the 'eighties. These were the following:—

The Peking Blind Mission in 1881; the Berlin Missionary Society in 1882; the Church of England Zenana Mission in 1884, when the French were at war with China; the German General Protestant Mission in 1885; the Bible Christians, which Society started its work as an associated Mission with the C.I.M. in 1885; the Christians Mission in the same year; the Foreign Christians Mission and the English Friends in 1886; the Swedish Mission in China and the German China Alliance, both associated with the C.I.M., in 1887 and 1889 respectively; the Scandinavian American Christian Free Church Mission and the Seventh Day Adventists in 1888; and the United Brethren in Christ in 1889.

Especial reference should be made to the rapid increase in the number of workers connected with the C.I.M. at this time. In 1881 special prayer began to be offered that God would send out seventy additional workers during the years 1882, 1883, 1884. The actual number sent was seventy-six. In 1885 some forty more followed, among whom were the well-known Cambridge Seven, six of whom are still engaged in the evangelisation of China, while the seventh, Mr. Studd, is still a warm missionary advocate. In 1887, in answer to prayer, God gave one hundred additional workers to the C.I.M. Of that number fifteen have died on the field and seven suffered martyrdom; twenty-four have retired after various terms of service, on the grounds of health, family claims, and other reasons; sixteen subsequently became connected with other Societies, of whom thirteen are still in China; while thirty-eight are still connected with the C.I.M. That more than fifty per cent of the hundred sent out in 1887 have been spared to devote twenty years of their lives for the evangelisation of Inland China is surely a cause for thankfulness.

Among the many noteworthy events connected with the rapid extension of missionary effort which succeeded the Conference of 1877, special mention must be made of the important development of women's work, especially in the interior. As early as 1844, Miss Aldersey, as an independent worker, had commenced her work among the women and girls at Ningpo; while in 1850 the American Protestant Episcopalian Church, the first Society to send a lady worker to China, sent out Miss L. M. Fay to Shanghai. The Berlin Foundling Home at Hongkong soon followed this example, while the American Methodist Episcopalian Mission sent the Misses B. and S. H. Woolston to Foochow in 1859. The American Presbyterians and American Baptists followed in 1866, the latter Society sending Miss A. M. Field to Swatow.

In 1866, when the C.I.M. Lammermuir party sailed, there were only fourteen unmarried ladies in China, of whom seven were at Hongkong, the others being stationed in six of the principal coast ports. In the Lammermuir party, however, were six single lady workers, in addition to two married ladies. At the Conference of 1877 there were sixty-two lady workers, not counting the missionaries' wives, so that the number had risen from fourteen to sixty-two in little over a decade.

With the famine of 1877-78 in Shansi, women's work in the interior may be said to have commenced, and the first party of ladies to go west consisted of Mrs. Hudson Taylor, Miss Horne, and Miss Crikmay, who reached Taiyuen Fu, the capital of the famine-stricken province, in October 1878. Within the short space of three years from this date, women workers connected with the C.I.M. had entered and settled in six of the inland provinces, besides taking the Gospel to hundreds of women living in Honan and Hunan, where residence was not then possible.

It was also at this time, through the energy and the appeals of Miss Foster of the Society for Promoting Female Education in the East,[14] that the Church of England Zenana Missionary Society extended their operations from India to China, commencing their work in the latter field in 1884. It is only necessary to refer to the Missionary statistics given on p. 39 to see to what proportions these small beginnings have grown.

A comparison of the statistics of the two Conferences of 1877 and 1890 show at a glance how rapid had been the progress made. The number of missionaries had increased from 473 to 1296; the converts from 13,035 to 37,287; the Chinese helpers from 660 to 1377; and the contributions of the Chinese Church from $9271 to $36,884.

As the details of recent missionary effort in China are still fresh within the memory of the majority of those who will read these pages, there is little need to do more than briefly enumerate the leading events which have either shaped or made manifest the wonderful movements of the last seventeen years, since the Conference of 1890.

Two outstanding events, however, connected with that Conference must not pass unrecorded. The first was the unexpected unanimity with which it was decided that Union versions of the Scriptures should be prepared in Mandarin, High Wen-li, and Easy Wen-li, a task so far completed that the results are ready for presentation to the Centenary Conference of 1907.

The second event was the appeal, issued by the Conference to the Protestant Churches of the world, to send out an additional thousand men within the next five years. God's answer to this prayer was the sending not of one thousand men, but of 1153 men and women.

The workers had barely returned to their stations after these notable meetings at Shanghai, when a series of anti-foreign riots commenced. All along the Yangtse there was considerable unrest, and riots at several centres—one at Wusueh resulting in the murder of one missionary connected with the Wesleyan body and of a Customs official. In the province of Fukien many of the workers also were shamefully treated, while a Presbyterian medical missionary in Manchuria was cruelly tortured. At the same time there commenced the wide circulation of the blasphemous placards which were issued from Hunan. In consequence of these and other disturbances, the Foreign Ministers of the various Powers presented a joint protocol to the Chinese Government in September 1891.

It was during the autumn of this latter year that the new departure of the C.M.S. connected with the name of the Eev. J. H. Horsburgh, the author of Do Not Say, took place, when a band of workers consisting of one clergyman, seven laymen, and five single ladies, with Mr. Horsburgh and his wife with two children, commenced a Mission in the north-west of Szechwan, from which has developed the present C.M.S. West China Mission. Connected with this movement must be mentioned the consecration of the Rev. W. W. Cassels, one of the C.I.M. "Cambridge Seven," as Bishop of West China.

While new workers and new Societies were entering into new spheres of work, the Chino-Japanese War suddenly broke out. The collapse of the Chinese before their island foe, whom they had, up to that time, despised as dwarfs, did not a little to somewhat rudely awaken China from her self-complacency and pride. With the awakening, however, there followed a period of serious unrest and trouble. In the west, the greater part of Szechwan was convulsed by serious riots, and many of the missionaries were for a time driven out of the province. This took place in May 1895. More serious trouble, however, was to follow, for in August of the same year the world was shocked by one of the worst missionary massacres of modern times. On the Hwa mountain, some twelve miles from Kucheng, in the province of Fukien, nine adult workers, with two children, connected with the C.M.S. and C.E.Z.M.S., were cruelly murdered on August 1, while others were severely wounded.

Dreadful and harrowing as were the facts connected with this massacre, it would be difficult to find a more beautiful illustration of that spirit which should characterise those who represent Christ to men than that which was manifested by the sorely stricken families and missionary Societies. The command to "pray for those who despitefully use you " was literally fulfilled, and a public meeting was immediately summoned in Exeter Hall, " not for protest, not for an appeal to the Government, but in solemn commemoration of the martyred brothers and sisters, and for united prayer. . . . Not one bitter word was uttered, nothing but sympathy with the bereaved, pity for the misguided murderers, thanksgiving for the holy lives of the martyrs, and fervent desires for the evangelisation of China."

How little did any one then know that within the short space of five years one of the worst persecutions known to history was to take place. Yet terrible as was the loss of life which subsequently took place during the awful Boxer outbreak of 1900, it would doubtless have been much greater but for the wonderful intervention of God Himself. During that sad year, the memory of which is still so painfully fresh, not only did 135 missionaries, with 53 of their children, lay down their lives for Christ in China, but thousands of Chinese Christians proved the reality of God's work in their hearts and lives by following in the footsteps of Him who is "The Faithful Witness."

Of the coup d'Mat of 1898; of the assumption of official rank by the Roman Catholic missionaries in China in 1899; of the seizure of Kiaochow by Germany in consequence of the murder of two Roman Catholic missionaries; of the Russian entry into Manchuria, and the fortification of Port Arthur ; of the British occupation of Weihaiwei; and of the other various demands upon the Chinese Empire, all of which more or less led up to the terrible revenge of 1900, there is now no need to speak.

Nor will space allow any adequate survey of the rapid and complex movements of the last few years, of the Russo-Japanese War, and the extraordinary collapse of the Russian army ; of the alliance between England and Japan, and the guarantee of her integrity to China by that agreement ; of the extraordinary thirst for Western knowledge, so recently manifested ; of the awakening of a new sense of national life, and the assumption of the watchword "China for the Chinese"; of the creation of a Chinese national army in contradistinction to provincial troops; of the courageous crusade against the opium curse; or to the many other developments in almost every department of Chinese life. These things are all known to those who have even superficially followed the course of events, which during the last few years have been re-shaping the Far East, and many of them are referred to, more or less in detail, in the separate articles which follow.

A perusal of the Table of Foreign Publications (see opposite page), translations of which can now be bought nearly all over China, will show at a glance how wide is the gulf between the but recent past, when all that was good was thought by the Chinese to be contained in Confucian literature, and the present, when they hungrily devour every variety of literature that the West can supply.

China has entered upon a new era in her history, and he would be a bold man who would dare to prophesy what the future has in store for the world in consequence. That China has immense and deep-seated evils to combat, her best friends know, and that she cannot make any serious progress without confronting many dangerous situations and fighting many a battle, is evident to all. He, therefore, who would be a friend to that land, and thereby a friend to the world, must be willing, at some sacrifice to himself and may be nation, to earnestly assist China in her desires for better things. "The elevation of China is not a thing to be afraid of, but her degradation is." Let the nations deal with her righteously; let England in particular cease her opium trade, and offer a helping hand to her in her present struggle with those evils which threaten her life; above all, let the Church of Christ take to heart more seriously than

she yet has done the overwhelming needs and claims of that great Empire, and China with its countless millions may yet be spared to bless the world. Foreign Publications which have been translated into Chinese

The name at the heading of each column shows the medium of translation

| Subject. | Roman Catholic. | Religious Tract Society. | Educational Association. | Diffusion Society. | Native Translations. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biblical Works | 3 | 67 | 2 | 10 | . . . |

| Church History | 7 | 1 | 1 | 9 | . . . |

| Christian Biographies | 16 | 9 | . . . | 11 | . . . |

| Theological Works | 35 | 9 | . . . | 10 | . . . |

| Apologetic Works | 28 | 4 | . . . | 10 | . . . |

| Devotional Works | 43 | 22 | . . . | 13 | . . . |

| Church Rules | 1 | 2 | . . . | 1 | . . . |

| Tracts | 124 | 398 | . . . | 60 | . . . |

| ——— | ——— | ——— | ——— | ||

| 257 | 512 | 3 | 124 |

| Subject. | Roman Catholic. | Religious Tract Society. | Educational Association. | Diffusion Society. | Native Translations. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comparative Religion | . . . | . . . | . . . | 5 | . . . |

| Philosophy | 1 | . . . | 2 | 13 | 40 |

| Ethics | . . . | . . . | 1 | . . . | . . . |

| Psychology | 2 | . . . | 1 | 1 | . . . |

| Medicine | 2 | . . . | 17 | 2 | 70 |

| Astronomy | 1 | . . . | 5 | 1 | 20 |

| Geography | 3 | 1 | 11 | 2 | 40 |

| Geology | . . . | . . . | 3 | . . . | . . . |

| Mineralogy | . . . | . . . | 3 | 1 | . . . |

| Universal History | . . . | . . . | 2 | 9 | 7 |

| National History | . . . | . . . | 5 | 7 | 83 |

| General Biographies | . . . | . . . | . . . | 11 | . . . |

| Mathematics | 3 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 70 |

| Physics | 5 | . . . | 21 | 5 | . . . |

| Chemistry | . . . | . . . | 10 | . . . | . . . |

| Electricity | . . . | . . . | 2 | 2 | . . . |

| Mechanics | . . . | . . . | 3 | . . . | 40 |

| Government | . . . | . . . | 1 | 4 | 60 |

| Law | . . . | . . . | 2 | 4 | 40 |

| Education | 12 | 2 | 19 | 17 | . . . |

| Language | . . . | . . . | . . . | . . . | 50 |

| Economics | . . . | . . . | 3 | 6 | 30 |

| Commerce | . . . | . . . | . . . | 2 | . . . |

| Industry | . . . | . . . | 13 | . . . | . . . |

| Agriculture | . . . | . . . | . . . | 1 | . . . |

| Statistics | 1 | . . . | . . . | 1 | 30 |

| Maps, Travels, Poetry, etc. | 6 | 16 | 40 | 33 | 130 |

| Miscellaneous | 5 | 32 | 3 | 10 | 340 |

| ——— | ——— | ——— | ——— | ——— | |

| 42 | 52 | 182 | 139 | 1,050 | |

| Class A | 257 | 512 | 3 | 124 | . . . |

| ——— | ——— | ——— | ——— | ——— | |

| Grand Total | 299 | 564 | 185 | 263 | 1,050 |

A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

Finland Missionary Society. Foi'eign Christian Mission. Friends' Foreign Mission . Gospel Mission Hauge's Synodes Mission . Hildesheim Mission for the Blind. Independent , Irish Presbyterian Church Mission. Loudon Missionary Society. Lutheran Brethren Mission. Methodist Episcopal Church (South), U.S.A. Methodist Episcopal Mis- sion. National Bible Society of

Scotland. A table should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Table for formatting instructions. |

tion of the Goj South Chihli Mis Swedish America ary Covenant. Swedish Baptist Swedish Missioua United Brethren United Evangelic ID afe o Scotland. Wesley an Missio Women's Union Yale University

Young Men's Comparative Table of China Missions

Showing Progress of Missions as reported at Conferences of 1877, 1890, and 1907.[15]

| 1877. | 1890. | 1907. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protestant Missionaries | 473 | 1,296 | 3,719 |

| Chinese Helpers | 750 | 1,657 | 9,998 |

| Communicants | 13,035 | 37,287 | 154,142 |

| Stations | 91 | ? | 706 |

| Out Stations | 511 | ? | 3,794 |

| Organised Churches | 312 | 522 | ... |

| Hospitals | 16 | 61 | 366 |

| Dispensaries | 24 | 44 | |

| Contributions of Native Church | $9,27 | $36,884 | ... |

| Day Schools | $15 | ... | 2,139 |

| Pupils in do. | 280 | Total Pupils, 16,836 |

42,738 |

| Boarding and Higher Schools | 7 | 255 | |

| Students in do. | 292 | 10,227 |

James Hudson Taylor.

THE PROVINCES OF CHINA

AND THE ISLAND OF FORMOSA

Comparative Table Showing Area and Population of the Provinces of China as compared with other well-known countries. Province and Country. Area, Square Miles. Population. The Province of Kwangtung ,970 ,865,251 Italy ,650 ,668,000 The Province of Fukien ,320 ,876,540 Portugal .... ,507 ,301,989 The Province of Chekiang . ,670 ,580,692 Bulgaria .... ,331 ,309,816 The Province of Kiangsu ,600 ,980,235 Portugal .... ,507 ,301,989 The Province of Shantung . ,970 ,247,900 Greece .... ,143 ,433,806 The Province of Chihli ,800 ,937,000 Austria .... ,922 ,895,413 The Province of Hupeh ,410 ,280,685 England and Wales ,307 ,002,525 The Province of Kiangsi ,480 ,532,125 Scotland and Ireland . ,420 ,730,397 The Province of Anhwei ,810 ,670,314 New York State . ,600 ,997,853 The Province of Honan ,940 ,316,800 Missouri ,735 ,679,184 The Province of Hunan ,380 ,169,673 Korea ,400 ,500,000 The Province of Kansu ,450 ,385,376 Norway ,445 ,988,674 The Province of Shensi ,270 ,450,182 Nebraska . ,840 ,058,910 The Province of Shansi ,830 ,200,456 Scotland and Ireland . ,420 ,730,397 The Province of Szechwan ,480 ,724,890 Madagascar ,560 ,500,000 The Province of Yunnan ,680 ,324,574 New Zealand ,657 ,651 The Province of Kweichow ,160 ,650,282 Victoria (Australia) ,451 ,140,405 The Province of Kwangsi ,200 ,142,330 Sweden ,970 ,009,632 The Province of Sinkiang ,590 ,000,000 Cape Colony ,690 ,727,000

- ↑

Area.

Eng. sq. miles.Population. China Proper 1,532,420 407,337,305 Dependencies— Manchuria 363,610 8,500,000 Mongolia 1,367,600 2,580,000 Tibet 463,200 6,430,000 Chinese Turkestan 550,340 1,200,000 Total 4,277,170 426,047,305 - ↑ See footnote on p. 2 from The Statesman's Year-Book.

- ↑ Du Halde, China, vol. i. p. 518.

- ↑ In the same year that Morrison sailed for China the Slave trade was abolished by Act of Parliament.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dr. Bridgman started the Chinese Repository in 1832, and Dr. Wells-Williams became the author of The Middle Kingdom, and was afterwards the Secretary of the U.S.A. Legation in China.

- ↑ Bishop Smith of Hongkong first went out in connection with the C.M.S. in 1844, but his health failing, he had to return home after two years' service. He was consecrated Bishop of Victoria, Hongkong, in 1849.

- ↑ Nanking being in the hands of the Taipings when the British Treaty was drawn up, the British Treaty does not name the Yangtse ports.

- ↑ The figures are taken from the statistical table as published in Mr. Hudson Taylor's original edition of China's Spiritual Needs and Claims. Mr. Hudson Taylor himself in his subsequent writings gives the number as 91, which figure has been frequently quoted by other writers. The details of the March 1865 statistical table are: 98 ordained and 14 lay missionaries; 206 Chinese assistants, of whom about a dozen were ordained; 3132 Chinese communicants; 25 Missionary assistants, of which 10 were American, 12 British, and 3 Continental.

- ↑ The Duke of Somerset's bitter attack upon Missions, made in the House of Lords at this time, received a crushing reply by Bishop Magee; the same Duke's subsequent attack on African Missions, also made in the Upper House, being answered by Archbishop Benson. Mr. Stock has pointed out that both of these replies were maiden speeches.

- ↑ Newchwang was opened as a port in 1861.

- ↑ The Chefoo Convention was not ratified until 1885. Although the Chinese fulfilled its stipulations, the British Government delayed its ratification for nine years, that it might exact more onerous conditions concerning the opium traffic.

- ↑ Of these men Mr. Stock has said: "Some of whom have since made a very definite mark in the history of Missions in China." Among them, special reference should be made to Adam Dorward, who gave eight years to itinerant work in Hunan (see Pioneer Work in Hunan, published by Morgan and Scott, 2s.), and Dr. Cameron, whose extensive journeys took him through seventeen out of eighteen provinces, not to speak of his itinerations in Manchuria, Mongolia, Eastern Tibet, and Burmah.

- ↑ Mr. Stevenson made an experimental journey across the border in the winter of 1879; returning to Bhamo, he with Mr. Soltau set out in 1880 on what was the first journey across China from west to east.

- ↑ This Society was formed as a result of the appeals of Mr. Abeel in England in 1834.

- ↑ As the official statistics presented to the Conference and those given in this book have been separately compiled, there will probably be some variations, especially as some Reports are so imperfectly furnished with statistics. Some reports actually give no statistics, and in not a few cases the figures needed are not easily found. Nothing more than an approximation is possible under existing conditions.—Ed.