The Choirmaster's Manual/Chapter 8

CHAPTER VIII

NOTATION, SIGHT-READING, ETC.

Most choirmasters, with but two practice-days a week, find themselves too fully occupied to teach the rudiments of music, time and sight-reading to the boys; but it is in the end a longer journey not to attempt it, than to spend a little extra time on these subjects in the first place. Choirboys should understand the ![]() (treble clef), the values and shapes of notes and Sip rests, sharps and flats, the staff, lines and spaces, dots, ties, bars, and the marks of expression in common use (a list of which will be found in the next chapter).

(treble clef), the values and shapes of notes and Sip rests, sharps and flats, the staff, lines and spaces, dots, ties, bars, and the marks of expression in common use (a list of which will be found in the next chapter).

Time. The upper figure shows the number of beats in a measure; the lower figure, the kind or value of note. ![]() 24 34 44

24 34 44 ![]() 22 32. Any upper figure into which 3 goes more than once, is "compound time," having so many groups of three notes 68 98 128 64, etc. If these upper figures are divided by 3, the number of beats in a measure is the result. Thus 68 divided by 3 gives two beats or groups of three notes each; as three notes always equal one dotted note of the next higher value, 68 equals 2 beats of dotted quarternotes, 4 being the next higher value to 8.

22 32. Any upper figure into which 3 goes more than once, is "compound time," having so many groups of three notes 68 98 128 64, etc. If these upper figures are divided by 3, the number of beats in a measure is the result. Thus 68 divided by 3 gives two beats or groups of three notes each; as three notes always equal one dotted note of the next higher value, 68 equals 2 beats of dotted quarternotes, 4 being the next higher value to 8.

Boys should now be made to fill up measures on the blackboard to which various time-signatures have been set, and when singing should beat time, commencing with two in a measure.

Always teach boys to accent the "down-stroke."

A common error in time is to sing soft passages slower than written.

Sight-Reading. The question of sight-reading offers a large field, but the general principle of using easy intervals first can readily be enlarged so as to suit particular cases. Starting with the Major scale, the notes "one above" or "one below" are easy to recognize. It is not advisable at this stage to point out the different qualities of a "Second," as long as the interval is correctly named.

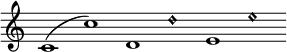

The next easy interval to recognize and sing is the octave. This has already been seen in Exercise 11. An octave always occupies, one line and one space with three lines between:

Note. In singing the common chord it may be well perhaps thus early to point to the fact that the three notes are super-imposed "Thirds," and the higher Third is smaller than the lower. In other words, the major chord is a minor Third on a major Third. By reversing the order of these Thirds, a minor chord is sounded. The author has often found it helpful to explain the principal difference of Major and Minor (especially "Thirds ") at the earliest opportunity.

To reach a 7th, strike the octave, and come back one, then sing the 7th direct. The addition or subtraction of a semitone, by the use of a sharp or flat, can be practised, and the names of keys and numbers of sharps and flats can all be added. (See "The Choir-Boy's Manual," companion-book to this.)

When the choir can sing the seven intervals of the octave, starting from a given keynote, they will, if attentive, count up from any other keynote and sing equally well.

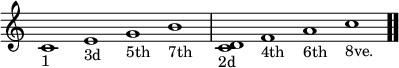

On the blackboard mark a keynote, then all the uneven intervals, 3d, 5th and 7th, then the even ones, 2d, 4th, 6th, 8th.

Pupils should now be able to name the interval from the keynote, by placing a series of notes on the board and pointing to them, thus:

Exercise 23.

Taking C as keynote, what interval is A? Sing it. Point out repeatedly that C to A, being a line and a space, must be an even interval.

Continue exercise in the following manner, pointing to notes:

C as keynote; what is E? Sing it.

F as keynote; what is A? Sing it.

D as keynote; what is G? Sing it.

And so on. This exercise repeated regularly will soon make the choir recognize all intervals, and sing those of the major scale correctly.

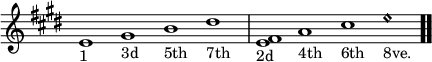

Note. After the key-signatures are understood, the quality of intervals can be explained, and sight-reading from the next note, and not from the keynote, can be practised until perfection is gained. In the following exercise, for instance,

Exercise 24.

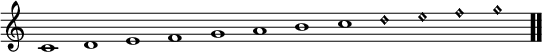

every interval could easily be sung as from the keynote C, according to the diatonic scale; but taking such notes as an interval above or below the note preceding it, it becomes plain (if only a major third has been learned, as a "line to next line," or "space to next space" interval), that D to F, or E to G, will be sung major until the minors are taught, or rather the key-signatures. Then, if it is recognized that the key of D requires two sharps (F and C), from D to F "natural" must be half a tone less. Intervals should be practised both from the keynote and back.

In reading from the "next note," that note is looked upon as a temporary keynote. It is unnecessary in a short work to enlarge on this; on the principle of sight-reading from probably a novel point of view, enough has been written for a choirmaster to proceed to the highest pitch of perfection.