The Czechoslovak Review/Volume 1/Condemnation of Kramar

Condemnation of Kramar.

If there was ever any doubt as to the sentiment of the Bohemian people and their sympathies in the present war, it has been removed in an authoritative way by an official communique of the Austrian government, dated January 5, 1917, which announces the commutation of the death sentences of Dr. Karel Kramar and his three co-defendants, and summarizes the evidence of their guilt.

The judgment of the highest military court of Vienna is a curiosity in this twentieth century. Since the days of the inquisition men have not been condemned for their beliefs or thoughts, but only for their acts. Kramar was found guilty of high treason because of what the court took to be his beliefs; and he was held responsible for the sentiments of the Czech people. You may not indict a nation, but you can indict and punish the nation through her leaders; that seems to be the standpoint of the men who dictated the judgment.

The judgment of the court and the official statement accompanying the judgment are of such instrinsic interest and shed so much light on conditions in Bohemia during the war that the full text of it deserves to be translated into English. It reads as follows:

“As has been announced before, Dr. Karel Kramar and Dr. Alois Rasin have been sentenced to death by the divisional military court for the crime of high treason, par. 58 of the Criminal Code, and for crime against the war power of the state, par. 32 of the Military Code. Vincenc Cervinka, secretary of the “Národní Listy” daily newspaper and Joseph Zamazal, clerk, have been sentenced to death for the crime of espionage. Kramar and Rasin have also been deprived of the degree of doctor of laws. The defendants applied for a writ of error. The supreme military court held a public hearing lasting eight days and refused the writ on Nov. 20, 1916, whereby the judgment went into effect.

But now His Majesty most graciously commuted the death sentences, and in place of them the following terms in the penitentiary at heavy labor were substituted: Karel Kramar 15 years, Alois Rasin 10 years, Vincenc Cervinka and Joseph Zamazal each 6 years.

The court in a lengthy opinion says:

Judgment of the lower court decided that Dr. Kramar as leader of the PanSlav propaganda in Bohemia and of the Czech movement in favor of Russia acted against the interests of the state both prior and subsequent to the outbreak of the war, by deliberate cooperation with plots aiming at the dismemberment of the monarchy. Not only in enemy countries, but also in neutral lands there was created a well organized and wide spread revolutionary propaganda which had for its purpose the partition of our monarchy by taking away from it Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia and Hungarian Slovakland, as well as other districts inhabited by Slavs. It also aimed to increase internal peril for the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, to organize rebellion and civil war and to employ all means for the erection of a Bohemian State, independent of Austria-Hungary. This propaganda was carried on partly by Bohemians who were settled in foreign lands or who fled after the opening of the war, such as Deputies Masaryk and Duerich, and Pavlu, a former editor of “Národní Listy”, who deserted as an ensign from the front, partly by foreigners who had interested themselves before the war in the so-called Bohemian question in a sense hostile to the monarchy, and after the war broke out manifested decided enmity against the empire, such as Denis, Leger, Cheradame, Count Bobrinski, Lieutenant-General Volodimirov and others.

Means used by this propaganda were these: publishing of newspapers serving the idea of dismemberment (La Nation Tchèque, L’Independance Tchecoslovaque, Čechoslovan, Čechoslovak), publication of expressions, declarations, programs and newspaper articles in other foreign periodicals, creating of societies and political committees working toward the above mentioned aims; meetings and conferences were held (in Prague 1908 and 1912, in Petrograd 1909 etc.), and finally Czech volunteer legions were organized and armed in Russia, France and England which fought in enemy armies.

In addition to that there appeared in certain districts among parts of the Czech people at home a series of demonstrations that not merely gave expression to sentiments hostile to the state, but actually tended to interfere with successful conduct of the war in a military and economic sense.

The judgment further declares that it has been proved that long before the war individual Bohemian statesmen, especially Kramar, under the guise of NeoSlavism used Slavic congresses and similar occasions to create and keep alive a movement that discussed Slavic reciprocity and cultural and racial aims, but actually developed treasonable designs, the true aim being the separation of Czechoslovak lands from the monarchy. The military court is convinced that this movement in which the defendant Kramar participated as one of the originators, organizers and leaders and in which the defendant Rasin participated only distantly, must be considered the principal cause and the real root of all the military and treasonable events at home and abroad, in the interior and at the front.

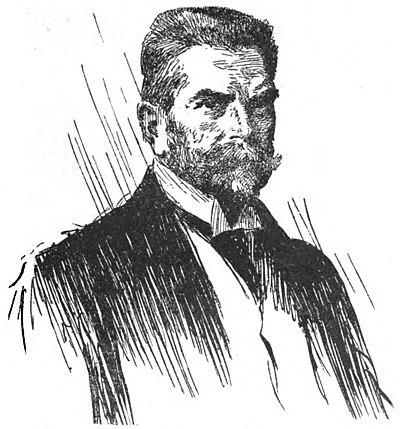

DR. KAREL KRAMÁŘ.

This causal connection which even the war did not interrupt between the aforesaid events and the accused can be traced especially from the following circumstances:

1. As far as revolutionary propaganda in foreign lands is concerned, it has been proved that the defendant Kramar maintained relations with editors, propagators and publishers of the treasonable periodicals abroad, especially with Brancianinov, Bobrinsky, Denis, Masaryk, Pavlu, Propper and others; that he was contributor to the “Novoje Zveno” newspaper which before the war and after the war openly demanded the destruction of the monarchy and specifically stated so on the title page. It is to be noticed that there exists remarkable agreement between the ideas, aims and phrases of the accused, of these treasonable publications and of the “Národní Listy.”

2. Dr. Kramar used the Národní Listy” as the herald of his politics and controlled its tendencies. Rasin also took part in this as contributing editor, although his activity was exerted in the economic and financial field and remained far behind Kramar’s tivity. Proof of Kramar’s influence in the “Národní Listy” are above all three articles, dated August 4, 1914, January 1, 1915 and April 6, 1915. In them Kramar is full of enthusiasm over the liberation of small nations which victory of the entente is expected to bring, whereby the nation will awake out of darkness and humiliation toward new life. The Bohemian nation will through its strength, unity and organization flourish anew after the catastrophe which this war will bring about.

The manner in which this newspaper was conducted for some time after the outbreak of the war was hostile to the monarchy in other ways also. Display of news favorable to our enemies, praise of their political and economic condition, pessimism over conditions in our monarchy, veiled admonitions to passive resistance with reference to war needs, especially the first two war loans, colored the contents of this newspaper.

3. An issue of “La Nation Tchèque”, a periodical published in France, contains numerous articles which set forth at length in the most objectionable manner the ideas and aims of the treasonable propaganda. This newspaper, shedding a clear light on the program of Kramar and those who agree with him, was found in Kramar’s pocket at the time of his arrest, and his excuse that the pages were not cut and that he did not know the contents was found to be false. The publisher of “La Nation Tchèque” is Professor Denis, a friend of Kramar, formerly a contributor to the “Národní Listy.” Other foreign printed matter of similar contents was found among Kramar’s effects, so especially Bohemian translation of two articles from the “London Times” of a similar tendency.

4. A serious indication that Kramar was guilty of criminal acts is his secret conversation with the Italian consul in a Prague hotel in April 1915 shortly before Italy declared war.

5. In the draft of a letter addressed to Governor Prince Thun found among Kramar’s papers Kramar stated explicitly that faithful to his political principles he was bound to avoid everything that would look like approval of the present war, and that his own attitude and the attitude of the “Národní Listy” toward the war loans was governed by this view.

The court is convinced that this conduct of the defendants is responsible for unfortunate occurrences which were committed by a part of the Bohemian people and placed serious obstacles in the way of successful prosecution of the war. In this respect we must mention the distribution of treasonable Russian proclamations in Bohemia and Moravia, expressions of sympathy for the enemy, frequent criminal prosecutions for political offences, failure of the plan to have the Bohemian deputies declare their loyalty at the beginning of the war, for which Kramar as leader of the representatives of the Bohemian people must be held primarily responsible; slight participation by population of the Czech race in the first two war loans, in the war collection of metals and collections for the Red Cross; organization of Czech volunteer legions in hostile lands; conduct of some Bohemian prisoners of war in enemy countries which ignored their duties and comradeship; unreliability of soldiers in certain parts of the army resulting in repeated voluntary surrenders to the enemy; insubordination of many Bohemian regiments both at the front and in garrison which were dangerous to the state and grossly violated all discipline, as a result of which military operations were seriously damaged and the enemy was enabled to gain successes. All this is in the opinion of the court the fruit of the agitation carried on for many years by Kramar and Rasin, and strengthens the case against them. The activities of the two defendants aimed at forcible territorial changes of the empire; they increased external danger and incited to insurrection in the interior (against par. 58c and 59b, Cr. Code); they tended to undermine our military power and caused serious losses, in violation of par. 32 of Military Code, constituting the crime against the war power of the state.

With reference to the defendants Zamazal and Cervinka the judgment found that Zamazal has been for years a Russophil and entertained ideas hostile to the state and that immediately after war broke out he undertook to spy out facts of military importance relating to the defense of the state and the plans of the army. For that purpose he collected with the help of sufficient expert knowledge reports and observations of military and strategical events and communicated them not only to individuals, but also to editors of papers, chiefly the “Národní Listy”. With the same aim in view he undertook two trips into the zone of operations, until arrested on suspicion of espionage.

Zamazal carried on relations with the “Národní Listy” through editorial secretary Vincenc Cervinka. It has been proved that Cervinka corresponded with traitors in foreign lands, such as Pavlu and others, by writing to a certain address in Roumania. Experts in military science see good circumstantial evidence in the fact that Cervinka advised Zamazal to write carefully, because this activity was to serve the enemy against the fatherland.

These proofs quoted from the judgment trace the main outlines of this entire organization hostile to the state both in its origin and development. However unpleasant may be this picture, it has nevertheless been proved by the process that a comparatively small part of the Bohemian nation and its leaders succumbed to criminal agitation. It would be a mistake to place the blame for these pitiful conditions upon the patriotic part of the Bohemian nation which condemns sharply these errors. This is especially so, since the present leadership of the Bohemian nation seriously attempts to bring back all the people to the Austrian state idea.

It should also be stated that the great majority of the Bohemian regiments excelled as always in brave fighting; that is proved by their bloody losses and many merited decorations. Let the guilty ones suffer the proper penalty. But it is right that general suspicion and condemnation should not be indulged in.”

The judgment pronounced upon Kramar and his fellow victims may be called a brief history of the movement for the Bohemian independence written from the point of view of the Hapsburg dynasty. The date of publication, January 5, is material. It was a few days after the rejection by the entente of the German peace feelers. Vienna saw that war must go on, that its outcome was extremely doubtful, that the work of Czech exiles was bearing fruit and that the active and passive resistance of Czechs at home seriously hampered the strength of Austria. The publication of the judgment, commutation of the death sentences and the commendation of the “patriotic” part of Bohemia and of the new Czech leadership represents a clumsy attempt on the part of the new premier, Count Clam-Martinic, to offer the olive branch to the rebellious Czechs. So far Count Clam-Martinic has not met with success. He has not obtained an expression of loyalty from the Bohemian deputies and he is still afraid to call a meeting of the parliament.

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1929 and is anonymous or pseudonymous due to unknown authorship. It is in the public domain in the United States as well as countries and areas where the copyright terms of anonymous or pseudonymous works are 95 years or less since publication.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse