The Czechoslovak Review/Volume 3/They, too, have labored

They, too, have labored

BY CHARLES PERGLER,

Commissioner of the Czechoslovak Republic in the United States.

It would be false modesty on the part of Czechoslovaks of America, if they did not feel quite proud of the role they played in the four year struggle for Czechoslovak independence, not only by way of raising the necessary funds to finance the revolutionary movement, but politically as well. This latter phase is frequently overlooked, and entirely too much stress is being laid on the purely financial part of the colony in the revolution. The fact is that im mediately upon the outbreak of the war our people in this country demonstrated their political maturity.

It must be remembered that communications with Bohemia became extremely difficult as soon as the hostilities commenced. There were all sorts of wild rumors. Every one was confident that the nation in its historical home would oppose to the utmost the designs of Vienna, Budapest, and Berlin. But there were, and could be, no directions from Prague, and if anything was to be done in America, any action taken had to be initiated entirely on lhis side of the Atlantic. It will remain to the eternal credit of the Czechoslovaks of America that, as soon as the famous ultimatum to Serbia was published, they demonstrated by all conceivable ways and methods their abhorrence of the dastardly Austrian, German, and Magyar attack upon the liberties of the world. We all remember the significant meeting in Chicago, particularly the one where the Sokols, in one of the halls of Chicago, removed the Austrian eagles they happened to see attached to the beams of the assembly room. The idea that the time to strike for Czechoslovak independence had arrived was not the property of one man, even in America, and thoughtful patriots in New York, in Chicago and elsewhere immediately began organizing the colony for all possible contingencies.

As soon as it was known that Masaryk succeeded in escaping into Switzerland, the raising of funds was started. This of itself had tremendous political significance, because, of course, no revolution can be conducted without money. The next step was to meet the insidious German propaganda so often masquerading in pacifist guise. And it was equally necessary to show that what became known as “hyphenism” did not prosper among Czechs and Slovaks. Even the American public still remembers the famous Czechoslovak memorandum to the President of the United States, declaring that the Czechs and Slovaks here owe their allegiance first of all to America; that they simply are citizens of Czechoslovak origin. In an open letter to Jane Addams, and American pacifists in general, it was pointed out that the pacifists’ attitude logically would lead to a destruction of the smaller nationalities by Germany and Austria-Hungary. And in 1916, during the presidential campaign, the Bohemian National Alliance demanded that Czechoslovaks, insofar as they are citizens, go to the polls simply as Americans, and nothing else, with the welfare of America in mind, and without being influenced by any other considerations.

It will always remain the pride of the Czechoslovak colony in America that in the United States, and only in the United States, the Czechoslovak cause, even while America was still neutral, was brought before a parlimentary forum in a hearing arranged by the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Representatievs as a result of a resolution by Representative London; later on, again before the Immigration and Naturalization Committee, and before the Legislature of the State of Texas.

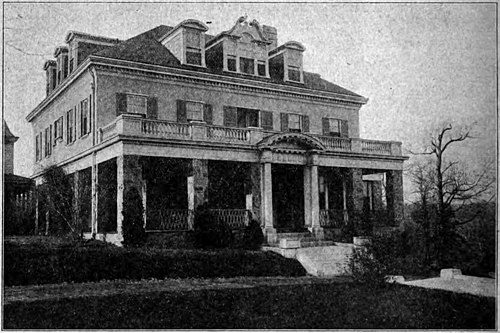

The word “propaganda” is not one pleasant to use, in view of its association with German methods. In fact, what the Czechoslovaks in America did was not a campaign of propaganda, but one of information. There is a distinction between the two terms. To inform means to tell the truth: to conduct propaganda does not necessarily mean telling the truth, as the Germans have abundantly shown us. It is not an exaggeration to say that in no other country did the Czechoslovak campaign of information reach the proportions it obtained in the United States. This is due largely to conditions, of course, but it is also due to the fact that it was thoroughly organized here. For quite a while there was hardly a gathering of importance which was not given an CZECHOSLOVAK LEGATION IN WASHINGTON.

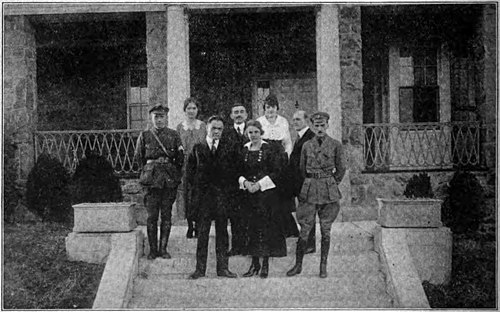

Bottom row—Charles Pergler, Czechoslovak Commissioner, Mrs. Pergler, Colonel Hurban.

Center row—Lieut. Zmrhal, Dr. Smetanka, Mr. Tvrzický.

Top row—Miss Kazamek, Miss Boor, stenographers.

It was thus that the Czechoslovaks of America helped to lay the foundation for the recognition of their nation’s aspirations by the United States of America, a recognition which came when President Wilson and the United States Government accorded the Czechoslovak National Council the status of a de facto government. And while in Europe these foundations were laid by that great leader Thomas G. Masaryk, in the United States his countrymen were forced to get along without his in comparable and unparalleled judgment, the benefit of which his co-workers in Europe all had at one time or another.

The Czechoslovaks of America have a right to claim that they, too, contributed to the triumph of the cause as a whole. The liberation of a nation is always a resultant of the interplay of various forces. One of these forces in the present struggle was the energy, force, and sound political thinking displayed by the Czechoslovaks of America. In the natural process of Americanization, which we all welcome, and which needs no artificial stimulation, some day there will cease to be such things as separate racial fragments in the United States. But a grateful Czechoslovak nation will always remember, as long as history is written, that before losing their identity in the melting pot of America, those who were forced to leave Bohemia and Slovakia because of Austrian and Magyar oppression, aided in achieving freedom and liberty for their native land.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1954, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 70 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse