The Encyclopedia Americana (1920)/Fox

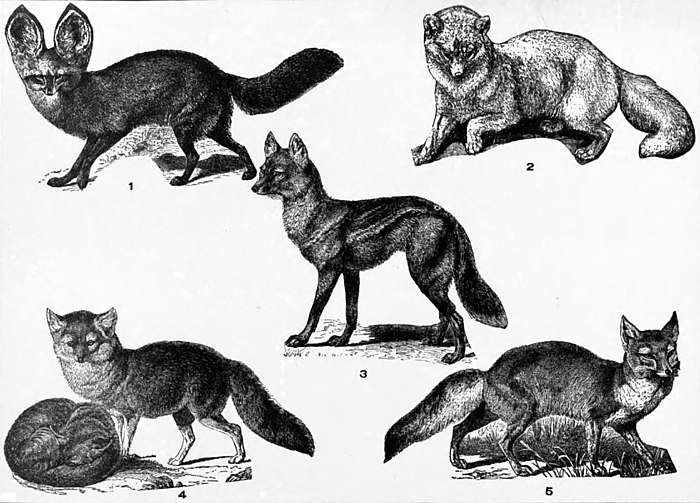

FOX, one of a group of small, long-eared, bushy-tailed animals of the dog-tribe (Canidæ), mostly included in the genus Vulpes; specifically, in literary usage, the red fox (V. vulgaris), called renard by the French and reinicke fuchs by the Germans. Foxes differ from wolves and jackals in being smaller, having shorter legs, longer, more furry and pointed ears, a more slender elongated muzzle, and a longer and more bushy tail; and they incline to that yellowish red color called “foxy.” But these distinctions are difficult of limitation (see Fennec; Foxdog), and some naturalists refuse to recognize a separate genus for them. One fixed character is found in the pupil of the eye, which when contracted becomes elliptical in the foxes but remains round in other dogs. All the typical foxes are inhabitants of northerly latitudes, and well represented by the common red fox, which may be regarded as distributed throughout the whole northern hemisphere, though variously named in different countries, where local diversities exhibit themselves; thus the American variety is called V. pennsylvanicus, but it is not essentially different from those of the Old World. Its variations are as great here as in Europe and Asia, especially among those of the Far North, where certain color-phases have superior value in the fur-trade. Thus a fox marked with a dark line along the spine and another over the shoulders, is called a “cross” fox, and fine specimens are worth an extra price. Wholly black ones are uncommon; but the rarest and most valuable pelt is that of a “silver” fox, that is, a black one in which so many hairs are white-tipped that a hoary or silvered appearance is given to the skin. The red fox is fostered for the sport of fox-hunting (q.v.) in Great Britain, and in some parts of Eastern America, but in most countries he is regarded merely as a fur-bearer, or a poultry thief or worse, and is trapped, shot and poisoned continuously. Nevertheless, the animal survives and multiplies in the midst of civilization, by virtue of its power of comprehension of and adaptation to new conditions; so that he has acquired, very justly, a reputation for alertness, wit and cunning in contrivance for food and safety. In America this species is constantly extending its range southward at the expense of the gray fox. Another species yielding a valuable fur is the Arctic or blue fox (V. lagopus), which is found on all Arctic coasts, and although brownish in summer, becomes in winter pure white; but the under fur is always bluish, and in those of Alaska this color prevails over brown in summer. Certain of the Aleutian Islands have lately been devoted by local fur companies to rearing these foxes in semi-captivity, where they are cared for, and a selected number annually sacrificed to trade. North America has two other well-marked species. One is the swift or kit fox (V. velox) of the plains, which is only 20 inches long, exceedingly swift of foot, expert in digging and cunning at concealment. It has reddish-yellow fur in summer, but becomes dull gray in winter, with black patches each side of the nose. The other species is the gray fox, which was once generally distributed over the United States but has become extinct in the northeastern part since the general clearing and settlement of the country. It is a woodland animal, still numerous in the South and West. Its hair is stiffer and duller in color than that of the red fox and it is so peculiar in structural respects (among others in having a concealed mane of stiff hairs on the top of the tail) that it has been classified in a separate genus as Urocyon argenteus. Several well-known species dwell in Asia, the best-known of which is the familiar fox of northern India (V. bengalensis).

Foxes everywhere are burrowing animals or else adapt to family needs holes in rocks, hollows of old stumps and similar conveniences. They hide by day and go abroad at night in search of small prey, stalking and catching birds on their nests, or at roost on the ground, ground-squirrels, mice, frogs and insects, and also eating largely of certain roots, fruits and other vegetable food. They are hardy, hunt all winter and climb mountain peaks. They never hunt in packs, as do wolves; and their voice is nearer a bark than a howl. They do not readily submit to domestication, and seem to have contributed little if anything to the composition of domestic breeds of dogs.

Consult for information on Old World foxes, the writings of Bell, Brehm, Blanford, Mivart and Beddard, well-summed up in Lydekker's ‘Royal Natural History’ (Vol. I). For American foxes, read Richardson, Hearne, Audubon, Merriam, the writings of Nelson, Turner and Murdoch on the natural history of Alaska, and the general remarks in Cram and Stone's ‘American Animals’ (1902).