The Grey Fairy Book/The Story of the Three Sons of Hali

THE STORY OF THE THREE SONS OF HALI

Till his eighteenth birthday the young Neangir lived happily in a village about forty miles from Constantinople, believing that Mohammed and Zinebi his wife, who had brought him up, were his real parents.

Neangir was quite content with his lot, though he was neither rich nor great, and unlike most young men of his age had no desire to leave his home. He was therefore completely taken by surprise when one day Mohammed told him with many sighs that the time had now come for him to go to Constantinople, and fix on a profession for himself. The choice would be left to him, but he would probably prefer either to be a soldier or one of the doctors learned in the law, who explain the Koran to the ignorant people. ‘You know the holy book nearly by heart,’ ended the old man, ‘so that in a very short time you would be fitted to teach others. But write to us and tell us how you pass your life, and we, on our side, will promise never to forget you.’

So saying, Mohammed gave Neangir four piastres to start him in the great city, and obtained leave for him to join a caravan which was about to set off for Constantinople.

The journey took some days, as caravans go very slowly, but at last the walls and towers of the capital appeared in the distance. When the caravan halted the travellers went their different ways, and Neangir was left, feeling very strange and rather lonely. He had plenty of courage and made friends very easily; still, not only was it the first time he had left the village where he had been brought up, but no one had ever spoken to him of Constantinople, and he did not so much as know the name of a single street or of a creature who lived in it.

Wondering what he was to do next, Neangir stood still for a moment to look about him, when suddenly a pleasant-looking man came up, and bowing politely, asked if the youth would do him the honour of staying in his house till he had made some plans for himself. Neangir, not seeing anything else he could do, accepted the stranger’s offer and followed him home.

They entered a large room, where a girl of about twelve years old was laying three places at the table.

‘Zelida,’ said the stranger, ‘was I not quite right when I told you that I should bring back a friend to sup with us?’

‘My father,’ replied the girl, ‘you are always right in what you say, and what is better still, you never mislead others.’ As she spoke, an old slave placed on the table a dish called pillau, made of rice and meat, which is a great favourite among people in the East, and setting down glasses of sherbet before each person, left the room quietly.

During the meal the host talked a great deal upon all sorts of subjects; but Neangir did nothing but look at Zelida, as far as he could without being positively rude.

The girl blushed and grew uncomfortable, and at last turned to her father. ‘The stranger’s eyes never wander from me,’ she said in a low and hesitating voice. ‘If Hassan should hear of it, jealousy will make him mad.’

‘No, no,’ replied the father, ‘you are certainly not for this young man. Did I not tell you before that I intend him for your sister Argentine. I will at once take measures to fix his heart upon her,’ and he rose and opened a cupboard, from which be took some fruits and a jug of wine, which he put on the table, together with a small silver and mother-of-pearl box.

‘Taste this wine,’ he said to the young man, pouring some into a glass.

‘Give me a little, too,’ cried Zelida.

‘Certainly not,’ answered her father, ‘you and Hassan both had as much as was good for you the other day.’

‘Then drink some yourself,’ replied she, ‘or this young man will think we mean to poison him.’

‘Well, if you wish, I will do so,’ said the father; ‘this elixir is not dangerous at my age, as it is at yours.’

When Neangir had emptied his glass, his host opened the mother-of-pearl box and held it out to him. Neangir was beside himself with delight at the picture of a young maiden more beautiful than anything he had ever dreamed of. He stood speechless before it, while his breast swelled with a feeling quite new to him.

His two companions watched him with amusement, until at last Neangir roused himself. ‘Explain to me, I pray you,’ he said, ‘the meaning of these mysteries. Why did you ask me here? Why did you force me to drink this dangerous liquid which has set fire to my blood? Why have you shown me this picture which has almost deprived me of reason?’

‘I will answer some of your questions,’ replied his host, ‘but all, I may not. The picture that you hold in your hand is that of Zelida’s sister. It has filled your heart with love for her; therefore, go and seek her. When you find her, you will find yourself.’

‘But where shall I find her?’ cried Neangir, kissing the charming miniature on which his eyes were fixed.

‘I am unable to tell you more,’ replied his host cautiously.

‘But I can,’ interrupted Zelida eagerly. ‘To-morrow you must go to the Jewish bazaar, and buy a watch from the second shop on the right hand. And at midnight———’

But what was to happen at midnight Neangir did not hear, for Zelida’s father hastily laid his hand over her mouth, crying: ‘Oh, be silent, child! Would you draw down on you by imprudence the fate of

your unhappy sisters?’ Hardly had he uttered the words, when a thick black vapour rose about him, proceeding from the precious bottle, which his rapid movement had overturned. The old slave rushed in and shrieked loudly, while Neangir, upset by this strange adventure, left the house.

He passed the rest of the night on the steps of a mosque, and with the first streaks of dawn he took his picture out of the folds of his turban. Then, remembering Zelida’s words, he inquired the way to the bazaar, and went straight to the shop she had described.

In answer to Neangir’s request to be shown some watches, the merchant produced several and pointed out the one which he considered the best. The price was three gold pieces, which Neangir readily agreed to give him; but the man made a difficulty about handing over the watch unless he knew where his customer lived.

‘That is more than I know myself,’ replied Neangir. ‘I only arrived in the town yesterday and cannot find the way to the house where I went first.’

‘Well,’ said the merchant, ‘come with me, and I will take you to a good Mussulman, where you will have everything you desire at a small charge.’

Neangir consented, and the two walked together through several streets till they reached the house recommended by the Jewish merchant. By his advice the young man paid in advance the last gold piece that remained to him for his food and lodging.

As soon as Neangir had dined he shut himself up in his room, and thrusting his hand into the folds of his turban, drew out his beloved portrait. As he did so, he touched a sealed letter which had apparently been hidden there without his knowledge, and seeing it was written by his foster-mother, Zinebi, he tore it eagerly open. Judge of his surprise when he read these words:

‘My dearest Child,—This letter, which you will some day find in your turban, is to inform you that you are not really our son. We believe your father to have been a great lord in some distant land, and inside this packet is a letter from him, threatening to be avenged on us if you are not restored to him at once. We shall always love you, but do not seek us or even write to us. It will be useless.’

In the same wrapper was a roll of paper with a few words as follows, traced in a hand unknown to Neangir:

‘Traitors, you are no doubt in league with those magicians who have stolen the two daughters of the unfortunate Siroco, and have taken from them the talisman given them by their father. You have kept my son from me, but I have found out your hiding-place and swear by the Holy Prophet to punish your crime. The stroke of my scimitar is swifter than the lightning.’

The unhappy Neangir on reading these two letters—of which he understood absolutely nothing—felt sadder and more lonely than ever. It soon dawned on him that he must be the son of the man who had written to Mohammed and his wife, but he did not know where to look for him, and indeed thought much more about the people who had brought him up and whom he was never to see again.

To shake off these gloomy feelings, so as to be able to make some plans for the future, Neangir left the house and walked briskly about the city till darkness had fallen. He then retraced his steps and was just crossing the threshold when he saw something at his feet sparkling in the moonlight. He picked it up, and discovered it to be a gold watch shining with precious stones. He gazed up and down the street to see if there was anyone about to whom it might belong, but there was not a creature visible. So he put it in his sash, by the side of a silver watch which he had bought from the Jew that morning.

The possession of this piece of good fortune cheered Neangir up a little, ‘for,’ thought he, ‘I can sell these jewels for at least a thousand sequins, and that will certainly last me till I have found my father.’ And consoled by this reflection he laid both watches beside him and prepared to sleep.

In the middle of the night he awoke suddenly and heard a soft voice speaking, which seemed to come from one of the watches.

‘Aurora, my sister,’ it whispered gently. ‘Did they remember to wind you up at midnight?’

‘No, dear Argentine,’ was the reply. ‘And you?’

‘They forgot me, too,’ answered the first voice, ‘and it is now one o’clock, so that we shall not be able to leave our prison till to-morrow—if we are not forgotten again—then.’

‘We have nothing now to do here,’ said Aurora. ‘We must resign ourselves to our fate—let us go.’

Filled with astonishment Neangir sat up in bed and beheld by the light of the moon the two watches slide to the ground and roll out of the room past the cats’ quarters. He rushed towards the door and on to the staircase, but the watches slipped downstairs without his seeing them, and into the street. He tried to unlock the door and follow them, but the key refused to turn, so he gave up the chase and went back to bed.

The next day all his sorrows returned with tenfold force. He felt himself lonelier and poorer than ever, and in a fit of despair he thrust his turban on his head, stuck his sword in his belt, and left the house determined to seek an explanation from the merchant who had sold him the silver watch.

When Neangir reached the bazaar he found the man he sought was absent from his shop, and his place filled by another Jew.

‘It is my brother you want,’ said he; ‘we keep the shop in turn, and in turn go into the city to do our business.’

‘Ah! what business?’ cried Neangir in a fury. ‘You are the brother of a scoundrel who sold me yesterday a watch that ran away in the night. But I will find it somehow, or else you shall pay for it, as you are his brother!’

‘What is that you say?’ asked the Jew, around whom a crowd had rapidly gathered. ‘A watch that ran away. If it had been a cask of wine, your story might be true, but a watch———! That is hardly possible!’

‘The Cadi shall say whether it is possible or not,’ replied Neangir, who at that moment perceived the other Jew enter the bazaar. Darting up, he seized him by the arm and dragged him to the Cadi’s house; but not before the man whom he had found in the shop contrived to whisper to his brother, in a tone loud enough for Neangir to hear, ‘Confess nothing, or we shall both be lost.’

When the Cadi was informed of what had taken place he ordered the crowd to be dispersed by blows, after the Turkish manner, and then asked Neangir to state his complaint. After hearing the young man’s story, which seemed to him most extraordinary, he turned to question the Jewish merchant, who instead of answering raised his eyes to heaven and fell down in a dead faint.

The judge took no notice of the swooning man, but told Neangir that his tale was so singular he really could not believe it, and that he should have the merchant carried back to his own house. This so enraged Neangir that he forgot the respect due to the Cadi, and exclaimed at the top of his voice, ‘Recover this fellow from his fainting fit, and force him to confess the truth,’ giving the Jew as he spoke a blow with his sword which caused him to utter a piercing scream.

‘You see for yourself,’ said the Jew to the Cadi, ‘that this young man is out of his mind. I forgive him his blow, but do not, I pray you, leave me in his power.’

At that moment the Bassa chanced to pass the Cadi’s house, and hearing a great noise, entered to inquire the cause. When the matter was explained he looked attentively at Neangir, and asked him gently how all these marvels could possibly have happened.

‘My lord,’ replied Neangir, ‘I swear I have spoken the truth, and perhaps you will believe me when I tell you that I myself have been the victim of spells wrought by people of this kind, who should be rooted out from the earth. For three years I was changed into a three-legged pot, and only returned to man’s shape when one day a turban was laid upon my lid.’

At these words the Bassa rent his robe for joy, and embracing Neangir, he cried, ‘Oh, my son, my son, have I found you at last? Do you not come from the house of Mohammed and Zinebi?’

‘Yes, my lord,’ replied Neangir, ‘it was they who took care of me during my misfortune, and taught me by their example to be less worthy of belonging to you.’

‘Blessed be the Prophet,’ said the Bassa, ‘who has restored one of my sons to me, at the time I least expected it! You know,’ he continued, addressing the Cadi, ‘that during the first years of my marriage I had three sons by the beautiful Zambac. When he was three years old a holy dervish gave the eldest a string of the finest coral, saying “Keep this treasure carefully, and be faithful to the Prophet, and you will be happy.” To the second, who now stands before you, he presented a copper plate on which the name of Mahomet was engraved in seven languages, telling him never to part from his turban, which was the sign of a true believer, and he would taste the greatest of all joys; while on the right arm of the third the dervish clasped a bracelet with the prayer that his right hand should be pure and he left spotless, so that he might never know sorrow.

‘My eldest son neglected the counsel of the dervish and terrible troubles fell on him, as also on the youngest. To preserve the second from similar misfortunes I brought him up in a lonely place, under the care of a faithful servant named Gouloucou, while I was fighting the enemies of our Holy Faith. On my return from the wars I hastened to embrace my son, but both he and Gouloucou had vanished, and it is only a few months since that I learned that the boy was living with a man called Mohammed, whom I suspected of having stolen him. Tell me, my son, how it came about that you fell into his hands.’

‘My lord,’ replied Neangir, ‘I can remember little of the early years of my life, save that I dwelt in a castle by the seashore with an old servant. I must have been about twelve years old when one day as we were out walking we met a man whose face was like that of this

Jew, coming dancing towards us. Suddenly I felt myself growing faint. I tried to raise my hands to my head, but they had become stiff and hard. In a word, I had been changed into a copper pot, and my arms formed the handle. What happened to my companion I know not, but I was conscious that someone had picked me up, and was carrying me quickly away.

‘After some days, or so it seemed to me, I was placed on the ground near a thick hedge, and when I heard my captor snoring beside me I resolved to make my escape. So I pushed my way among the thorns as well as I could, and walked on steadily for about an hour.

‘You cannot imagine, my lord, how awkward it is to walk with three legs, especially when your knees are as stiff as mine were. At length after much difficulty I reached a market-garden, and hid myself deep down among the cabbages, where I passed a quiet night.

‘The next morning, at sunrise, I felt some one stooping over me and examining me closely. “What have you got there, Zinebi?” said the voice of a man a little way off.

‘“The most beautiful pot in the whole world,” answered the woman beside me, “and who would have dreamed of finding it among my cabbages!”

‘Mohammed lifted me from the ground and looked at me with admiration. That pleased me, for everyone likes to be admired, even if he is only a pot! And I was taken into the house and filled with water, and put on the fire to boil.

‘For three years I led a quiet and useful life, being scrubbed bright every day by Zinebi, then a young and beautiful woman.

‘One morning Zinebi set me on the fire, with a fine fillet of beef inside me to cook for dinner. Being afraid that some of the steam would escape through the lid, and that the taste of her stew would be spoilt, she looked about for something to put over the cover, but could see nothing handy but her husband’s turban. She tied it firmly round the lid, and then left the room. For the first time during three years I began to feel the fire burning the soles of my feet, and moved away a little—doing this with a great deal more ease than I had felt when making my escape to Mohammed’s garden. I was somehow aware, too, that I was growing taller; in fact in a few minutes I was a man again.

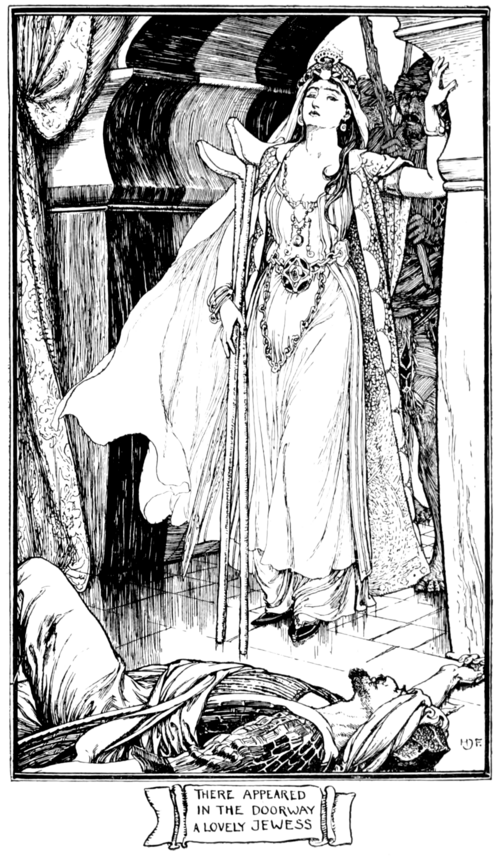

Whilst Neangir was speaking, the blood from the Jew’s wound had gradually ceased to flow; and at this moment there appeared in the doorway a lovely Jewess, about twenty-two years old, her hair and her dress all disordered, as if she had been flying from some great danger. In one hand she held two crutches of white wood, and was followed by two men. The first man Neangir knew to be the brother of the Jew he had struck with his sword, while in the second the young man thought he recognised the person who was standing by when he was changed into a pot. Both of these men had a wide linen band round their thighs and held stout sticks.

The Jewess approached the wounded man and laid the two crutches near him; then, fixing her eyes on him, she burst into tears.

‘Unhappy Izouf,’ she murmured, ‘why do you suffer yourself to be led into such dangerous adventures? Look at the consequences, not only to yourself, but to your two brothers,’ turning as she spoke to the men who had come in with her, and who had sunk down on the mat at the feet of the Jew.

The Bassa and his companions were struck both with the beauty of the Jewess and also with her words, and begged her to give them an explanation.

‘My lords,’ she said, ‘my name is Sumi, and I am the daughter of Moïzes, one of our most famous rabbis. I am the victim of my love for Izaf,’ pointing to the man who had entered last, ‘and in spite of his ingratitude, I cannot tear him from my heart. Cruel enemy of my life,’ she continued turning to Izaf, ‘tell these gentlemen your story and that of your brothers, and try to gain your pardon by repentance.’

‘We all three were born at the same time,’ said the Jew, obeying the command of Sumi at a sign from the Cadi, ‘and are the sons of the famous Nathan Ben-Sadi, who gave us the names of Izif, Izouf, and Izaf. From our earliest years we were taught the secrets of magic, and as we were all born under the same stars we shared the same happiness and the same troubles.

‘Our mother died before I can remember, and when we were fifteen our father was seized with a dangerous illness which no spells could cure. Feeling death draw near, he called us to his bedside and took leave of us in these words:

‘“My sons, I have no riches to bequeath to you; my only wealth was those secrets of magic which you know. Some stones you already have, engraved with mystic signs, and long ago I taught you how to make others. But you still lack the most precious of all talismans—the three rings belonging to the daughters of Siroco. Try to get possession of them, but take heed on beholding these young girls that you do not fall under the power of their beauty. Their religion is different from yours, and further, they are the betrothed brides of the sons of the Bassa of the Sea. And to preserve you from a love which can bring you nothing but sorrow, I counsel you in time of peril to seek out the daughter of Moïzes the Rabbi, who cherishes a hidden passion for Izaf, and possesses the Book of Spells, which her father himself wrote with the sacred ink that was used for the Talmud.” So saying, our father fell back on his cushions and died, leaving us burning with desire for the three rings of the daughters of Siroco.

At the second of these names, both the Bassa and his Son gave a start of surprise, but they said nothing and Izaf went on with his story.

‘The first thing to be done was to put on a disguise, and it was in the dress of foreign merchants that we at length approached the young ladies, taking care to carry with us a collection of fine stones which we had hired for the occasion. But alas! it was to no purpose that Nathan Ben-Sadi had warned us to close our hearts against their charms! The peerless Aurora was clothed in a garment of golden hue, studded all over with flashing jewels; the fair-haired Argentine wore a dress of silver, and the young Zelida, loveliest of them all, the costume of a Persian lady.

‘Among other curiosities that we had brought with us, was a flask containing an elixir which had the quality of exciting love in the breasts of any man or woman who drank of it. This had been given me by the fair Sumi, who had used it herself and was full of wrath because I refused to drink it likewise, and so return her passion. I showed this liquid to the three maidens who were engaged in examining the precious stones, and choosing those that pleased them best; and I was in the act of pouring some in a crystal cup, when Zelida’s eyes fell on a paper wrapped round the flask containing these words. “Beware lest you drink this water with any other man than him who will one day be your husband.” “Ah, traitor!” she exclaimed, “what snare have you laid for me?” and glancing where her finger pointed I recognised the writing of Sumi.

‘By this time my two brothers had already got possession of the rings of Aurora and Argentine in exchange for some merchandise which they coveted, and no sooner had the magic circles left their hands than the two sisters vanished completely, and in their place nothing was to be seen but a watch of gold and one of silver. At this instant the old slave whom we had bribed to let us enter the house, rushed into the room announcing the return of Zelida’s father. My brothers, trembling with fright, hid the watches in their turbans, and while the slave was attending to Zelida, who had sunk fainting to the ground, we managed to make our escape.

‘Fearing to be traced by the enraged Siroco, we did not dare to go back to the house where we lodged, but took refuge with Sumi.

‘“Unhappy wretches!” cried she, “is it thus that you have followed the counsels of your father? This very morning I consulted my magic books, and saw you in the act of abandoning your hearts to the fatal passion which will one day be your ruin. No, do not think I will tamely bear this insult! It was I who wrote the letter which stopped Zelida in the act of drinking the elixir of love! As for you,” she went on, turning to my brothers, “you do not yet know what those two watches will cost you! But you can learn it now, and the knowledge of the truth will only serve to render your lives still more miserable.”

‘As she spoke she held out the sacred book written by Moïzes, and pointed to the following lines:

‘“If at midnight the watches are wound with the key of gold and the key of silver, they will resume their proper shapes during the first hour of the day. They will always remain under the care of a woman, and will come back to her wherever they may be. And the woman appointed to guard them is the daughter of Moïzes.”

‘My brothers were full of rage when they saw themselves outwitted, but there was no help for it. The watches were delivered up to Sumi and they went their way, while I remained behind curious to see what would happen.

‘As night wore on Sumi wound up both watches, and when midnight struck Aurora and her sister made their appearance. They knew nothing of what had occurred and supposed they had just awakened from sleep, but when Sumi’s story made them understand their terrible fate, they both sobbed with despair and were only consoled when Sumi promised never to forsake them. Then one o’clock sounded, and they became watches again.

‘All night long I was a prey to vague fears, and I felt as if something unseen was pushing me on—in what direction I did not know. At dawn I rose and went out, meeting Izif in the street suffering from the same dread as myself. We agreed that Constantinople was no place for us any longer, and calling to Izouf to accompany us, we left the city together, but soon determined to travel separately, so that we might not be so easily recognised by the spies of Siroco.

‘A few days later I found myself at the door of an old castle near the sea, before which a tall slave was pacing to and fro. The gift of one or two worthless jewels loosened his tongue, and he informed me that he was in the service of the son of the Bassa of the Sea, at that time making war in distant countries. The youth, he told me, had been destined from his boyhood to marry the daughter of Siroco, whose sisters were to be the brides of his brothers, and went on to speak of the talisman that his charge possessed. But I could think of nothing but the beautiful Zelida, and my passion, which I thought I had conquered, awoke in full force.

‘In order to remove this dangerous rival from my path, I resolved to kidnap him, and to this end I began to act a madman, and to sing and dance loudly, crying to the slave to fetch the boy and let him see my tricks. He consented, and both were so diverted with my antics that they laughed till the tears ran down their cheeks, and even tried to imitate me. Then I declared I felt thirsty and begged the slave to fetch me some water, and while he was absent I advised the youth to take off his turban, so as to cool his head. He complied gladly, and in the twinkling of an eye was changed into a pot. A cry from the slave warned me that I had no time to lose if I would save my life, so I snatched up the pot and fled with it like the wind.

‘You have heard, my lords, what became of the pot, so I will only say now that when I awoke it had disappeared; but I was partly consoled for its loss by finding my two brothers fast asleep not far from me. “How did you get here?” I inquired, “and what has happened to you since we parted?”

‘“Alas!” replied Izouf, “we were passing a wayside inn from which came sounds of songs and laughter, and fools that we were—we entered and sat down. Circassian girls of great beauty were dancing for the amusement of several men, who not only received us politely, but placed us near the two loveliest maidens. Our happiness was complete, and time flew unknown to us, when one of the Circassians leaned forward and said to her sister, ‘Their brother danced, and they must dance too.’ What they meant by these words I know not, but perhaps you can tell us?”

‘“I understand quite well,” I replied. “They were thinking of the day that I stole the son of the Bassa, and had danced before him.”

‘“Perhaps you are right,” continued Izouf, “for the two ladies took our hands and danced with us till we were quite exhausted, and when at last we sat down a second time to table we drank more wine than was good for us. Indeed, our heads grew so confused, that when the men jumped up and threatened to kill us, we could make no resistance and suffered ourselves to be robbed of everything we had about us, including the most precious possession of all, the two talismans of the daughters of Siroco.”

‘Not knowing what else to do, we all three returned to Constantinople to ask the advice of Sumi, and found that she was already aware of our misfortunes, having read about them in the book of Moïzes. The kind-hearted creature wept bitterly at our story, but, being poor herself, could give us little help. At last I proposed that every morning we should sell the silver watch into which Argentine was changed, as it would return to Sumi every evening unless it was wound up with the silver key—which was not at all likely. Sumi consented, but only on the condition that we would never sell the watch without ascertaining the house where it was to be found, so that she might also take Aurora thither, and thus Argentine would not be alone if by any chance she was wound up at the mystic hour. For some weeks now we have lived by this means, and the two daughters of Siroco have never failed to return to Sumi each night. Yesterday Izouf sold the silver watch to this young man, and in the evening placed the gold watch on the steps by order of Sumi, just before his customer entered the house; from which both watches came back early this morning.’

‘If I had only known!’ cried Neangir. ‘If I had had more presence of mind, I should have seen the lovely Argentine, and if her portrait is so fair, what must the original be!’

‘It was not your fault,’ replied the Cadi, ‘you are no magician; and who could guess that the watch must be wound at such an hour? But I shall give orders that the merchant is to hand it over to you, and this evening you will certainly not forget.’

‘It is impossible to let you have it to-day,’ answered Izouf, ‘for it is already sold.’

‘If that is so,’ said the Cadi, ‘you must return the three gold pieces which the young man paid.’

The Jew, delighted to get off so easily, put his hand in his pocket, when Neangir stopped him.

‘No, no,’ he exclaimed, ‘it is not money I want, but the adorable Argentine; without her everything is valueless.’

‘My dear Cadi,’ said the Bassa, ‘he is right. The treasure that my son has lost is absolutely priceless.’

‘My lord,’ replied the Cadi, ‘your wisdom is greater than mine. Give judgment I pray you in the matter.’

So the Bassa desired them all to accompany him to his house, and commanded his slaves not to lose sight of the three Jewish brothers.

When they arrived at the door of his dwelling, he noticed two women sitting on a bench close by, thickly veiled and beautifully dressed. Their wide satin trousers were embroidered in silver, and their muslin robes were of the finest texture. In the hand of one was a bag of pink silk tied with green ribbons, containing something that seemed to move.

At the approach of the Bassa both ladies rose, and came towards him. Then the one who held the bag addressed him saying, ‘Noble lord, buy, I pray you, this bag, without asking to see what it contains.’

‘How much do you want for it?’ asked the Bassa.

‘Three hundred sequins,’ replied the unknown.

At these words the Bassa laughed contemptuously, and passed on without speaking.

‘You will not repent of your bargain,’ went on the woman. ‘Perhaps if we come back to-morrow you will be glad to give us the four hundred sequins we shall then ask. And the next day the price will be five hundred.’

‘Come away,’ said her companion, taking hold of her sleeve. ‘Do not let us stay here any longer. It may cry, and then our secret will be discovered.’ And so saying, the two young women disappeared.

The Jews were left in the front hall under the care of the slaves, and Neangir and Sumi followed the Bassa inside the house, which was magnificently furnished. At one end of a large, brilliantly-lighted room a lady of about thirty-five years old reclined on a couch, still beautiful in spite of the sad expression of her face.

‘Incomparable Zambac,’ said the Bassa, going up to her, ‘give me your thanks, for here is the lost son for whom you have shed so many tears,’ but before his mother could clasp him in her arms Neangir had flung himself at her feet.

‘Let the whole house rejoice with me,’ continued the Bassa, ‘and let my two sons Ibrahim and Hassan be told, that they may embrace their brother.’

‘Alas! my lord!’ said Zambac, ‘do you forget that this is the hour when Hassan weeps on his hand, and Ibrahim gathers up his coral beads?’

‘Let the command of the Prophet be obeyed,’ replied the Bassa; ‘then we will wait till the evening.’

‘Forgive me, noble lord,’ interrupted Sumi, ‘but what is this mystery? With the help of the Book of Spells perhaps I may be of some use in the matter.’

‘Sumi,’ answered the Bassa, ‘I owe you already the happiness of my life; come with me then, and the sight of my unhappy sons will tell you of our trouble better than any words of mine.’

The Bassa rose fr m his divan and drew aside the hangings leading to a large hall, closely followed by Neangir and Sumi. There they saw two young men, one about seventeen, and the other nineteen years of age. The younger was seated before a table, his forehead resting on his right hand, which he was watering with his tears. He raised his head for a moment when his father entered, and Neangir and Sumi both saw that this hand was of ebony.

The other young man was occupied busily in collecting coral beads which were scattered all over the floor of the room, and as he picked them up he placed them on the same table where his brother was sitting. He had already gathered together ninety-eight beads, and thought they were all there, when they suddenly rolled off the table and he had to begin his work over again.

‘Do you see,’ whispered the Bassa, ‘for three hours daily one collects these coral beads, and for the same space of time the other laments over his hand which has become black, and I am wholly ignorant what is the cause of either misfortune.’

‘Do not let us stay here,’ said Sumi, ‘our presence must add to their grief. But permit me to fetch the Book of Spells, which I feel sure will tell us not only the cause of their malady but also its cure.’

The Bassa readily agreed to Sumi’s proposal, but Neangir objected strongly. ‘If Sumi leaves us,’ he said to his father, ‘I shall not see my beloved Argentine when she returns to-night with the fair Aurora. And life is an eternity till I behold her.’

‘Be comforted,’ replied Sumi. ‘I will be back before sunset; and I leave you my adored Izaf as a pledge.’

Scarcely had the Jewess left Neangir, when the old female slave entered the hall where the three Jews still remained carefully guarded, followed by a man whose splendid dress prevented Neangir from recognising at first as the person in whose house he had dined two days before. But the woman he knew at once to be the nurse of Zelida.

He started eagerly forward, but before he had time to speak the slave turned to the soldier she was conducting. ‘My lord,’ she said, ‘those are the men; I have tracked them from the house of the Cadi to this palace. They are the same; I am not mistaken, strike and avenge yourself.’

As he listened the face of the stranger grew scarlet with anger. He drew his sword and in another moment would have rushed on the Jews, when Neangir and the slaves of the Bassa seized hold of him.

‘What are you doing?’ cried Neangir. ‘How dare you attack those whom the Bassa has taken under his protection?’

‘Ah, my son,’ replied the soldier, ‘the Bassa would withdraw his protection if he knew that these wretches have robbed me of all I have dearest in the world. He knows them as little as he knows you.’

‘But he knows me very well,’ replied Neangir, ‘for he has recognised me as his son. Come with me now into his presence.’

The stranger bowed and passed through the curtain held back by Neangir, whose surprise was great at seeing his father spring forward and clasp the soldier in his arms.

‘What! is it you, my dear Siroco?’ cried he. ‘I believed you had been slain in that awful battle when the followers of the Prophet were put to flight. But why do your eyes kindle with the flames they shot forth on that fearful day? Calm yourself and tell me what I can do to help you. See, I have found my son, let that be a good omen for your happiness also.’

‘I did not guess,’ answered Siroco, ‘that the son you have so long mourned had come back to you. Some days since the Prophet appeared to me in a dream, floating in a circle of light, and he said to me, “Go to-morrow at sunset to the Galata Gate, and there you will find a young man whom you must bring home with you. He is the second son of your old friend the Bassa of the Sea, and that you may make no mistake, put your fingers in his turban and you will feel the plaque on which my name is engraved in seven different languages.”

‘I did as I was bid,’ went on Siroco, ‘and so charmed was I with his face and manner that I caused him to fall in love with Argentine, whose portrait I gave him. But at the moment when I was rejoicing in the happiness before me, and looking forward to the pleasure of restoring you your son, some drops of the elixir of love were spilt on the table, and caused a thick vapour to arise, which hid everything. When it had cleared away he was gone. This morning my old slave informed me that she had discovered the traitors who had stolen my daughters from me, and I hastened hither to avenge them. But I place myself in your hands, and will follow your counsel.’

‘Fate will favour us, I am sure,’ said the Bassa, ‘for

A rustling of silken stuffs drew their eyes to the door, and Ibrahim and Hassan, whose daily penance had by this time been performed, entered to embrace their brother. Neangir and Hassan, who had also drunk of the elixir of love, could think of nothing but the beautiful ladies who had captured their hearts, while the spirits of Ibrahim had been cheered by the news that the daughter of Moïzes hoped to find in the Book of Spells some charm to deliver him from collecting the magic beads.

It was some hours later that Sumi returned, bringing with her the sacred book.

‘See,’ she said, beckoning to Hassan, ‘your destiny is written here.’ And Hassan stooped and read these words in Hebrew: ‘His right hand has become black as ebony from touching the fat of an impure animal, and will remain so till the last of its race is drowned in the sea.’

‘Alas!’ sighed the unfortunate youth. ‘It now comes back to my memory. One day the slave of Zambac was making a cake. She warned me not to touch, as the cake was mixed with lard, but I did not heed her, and in an instant my hand became the ebony that it now is.’

‘Holy dervish!’ exclaimed the Bassa, ‘how true were your words! My son has neglected the advice you gave him on presenting him the bracelet, and he has been severely punished. But tell me, O wise Sumi, where I can find the last of the accursed race who has brought this doom on my son?’

‘It is written here,’ replied Sumi, turning over some leaves. ‘The little black pig is in the pink bag carried by the two Circassians.’

When he read this the Bassa sank on his cushions in despair.

‘Ah,’ he said, ‘that is the bag that was offered me this morning for three hundred sequins. Those must be the women who caused Izif and Izouf to dance, and took from them the two talismans of the daughters of Siroco. They only can break the spell that has been cast on us. Let them be found and I will gladly give them the half of my possessions. Idiot that I was to send them away!’

While the Bassa was bewailing his folly, Ibrahim in his turn had opened the book, and blushed deeply as he read the words: ‘The chaplet of beads has been defiled by the game of “Odd and Even.” Its owner has tried to cheat by concealing one of the numbers. Let the faithless Moslem seek for ever the missing bead.’

‘O heaven,’ cried Ibrahim, ‘that unhappy day rises up before me. I had cut the thread of the chaplet, while playing with Aurora. Holding the ninety-nine beads in my hand she guessed “Odd,” and in order that she might lose I let one bead fall from my hand. Since then I have sought it daily, but it never has been found.’

‘Holy dervish!’ cried the Bassa, ‘how true were your words! From the time that the sacred chaplet was no longer complete, my son has borne the penalty. But may not the Book of Spells teach us how to deliver Ibrahim also?’

‘Listen,’ said Sumi, ‘this is what I find: “The coral bead lies in the fifth fold of the dress of yellow brocade.”’

‘Ah, what good fortune!’ exclaimed the Bassa; ‘we shall shortly see the beautiful Aurora, and Ibrahim shall at once search in the fifth fold of her yellow brocade. For it is she no doubt of whom the book speaks.’

As the Jewess closed the Book of Moïzes, Zelida appeared, accompanied by a whole train of slaves and her old nurse. At her entrance Hassan, beside himself with joy, flung himself on his knees and kissed her hand.

‘My lord,’ he said to the Bassa, ‘pardon me these transports. No elixir of love was needed to inflame my heart! Let the marriage rite make us speedily one.’

‘My son, are you mad?’ asked the Bassa. ‘As long as the misfortunes of your brothers last, shall you alone

be happy? And whoever heard of a bridegroom with a black hand? Wait yet a little longer, till the black pig is drowned in the sea.’

‘Yes! dear Hassan,’ said Zelida, ‘our happiness will be increased tenfold when my sisters have regained their proper shapes. And here is the elixir which I have brought with me, so that their joy may equal ours.’ And she held out the flask to the Bassa, who had it closed in his presence.

Zambac was filled with joy at the sight of Zelida, and embraced her with delight. Then she led the way into the garden, and invited all her friends to seat themselves under the thick overhanging branches of a splendid jessamine tree. No sooner, however, were they comfortably settled, than they were astonished to hear a man’s voice, speaking angrily on the other side of the wall.

‘Ungrateful girls!’ it said, ‘is this the way you treat me? Let me hide myself for ever! This cave is no longer dark enough or deep enough for me.’

A burst of laughter was the only answer, and the voice continued, ‘What have I done to earn such contempt? Was this what you promised me when I managed to get for you the talismans of beauty? Is this the reward I have a right to expect when I have bestowed on you the little black pig, who is certain to bring you good luck?’

At these words the curiosity of the listeners passed all bounds, and the Bassa commanded his slaves instantly to tear down the wall. It was done, but the man was nowhere to be seen, and there were only two girls of extraordinary beauty, who seemed quite at their ease, and came dancing gaily on to the terrace. With them was an old slave in whom the Bassa recognised Gouloucou, the former guardian of Neangir.

Gouloucou shrank with fear when he saw the Bassa, as he expected nothing less than death at his hands for allowing Neangir to be snatched away. But the Bassa made him signs of forgiveness, and asked him how he had escaped death when he had thrown himself from the cliff. Gouloucou explained that he had been picked up by a dervish who had cured his wounds, and had then given him as slave to the two young ladies now before the company, and in their service he had remained ever since.

‘But,’ said the Bassa, ‘where is the little black pig of which the voice spoke just now?’

‘My lord,’ answered one of the ladies, ‘when at your command the wall was thrown down, the man whom you heard speaking was so frightened at the noise that he caught up the pig and ran away.’

‘Let him be pursued instantly,’ cried the Bassa; but the ladies smiled.

‘Do not be alarmed, my lord,’ said one, ‘he is sure to return. Only give orders that the entrance to the cave shall be guarded, so that when he is once in he shall not get out again.’

By this time night was falling and they all went back to the palace, where coffee and fruits were served in a splendid gallery, near the women’s apartments. The Bassa then ordered the three Jews to be brought before him, so that he might see whether these were the two damsels who had forced them to dance at the inn, but to his great vexation it was found that when their guards had gone to knock down the wall the Jews had escaped.

At this news the Jewess Sumi turned pale, but glancing at the Book of Spells her face brightened, and she said half aloud, ‘There is no cause for disquiet; they will capture the dervish,’ while Hassan lamented loudly that as soon as fortune appeared on one side she fled on the other!

On hearing this reflection one of the Bassa’s pages broke into a laugh. ‘This fortune comes to us dancing, my lord,’ said he, ‘and the other leaves us on crutches. Do not be afraid. She will not go very far.’

The Bassa, shocked at his impertinent interference, desired him to leave the room and not to come back till he was sent for.

‘My lord shall be obeyed,’ said the page, ‘but when I return, it shall be in such good company that you will welcome me gladly.’ So saying, he went out.

When they were alone, Neangir turned to the fair strangers and implored their help. ‘My brothers and myself,’ he cried, ‘are filled with love for three peerless maidens, two of whom are under a cruel spell. If their fate happened to be in your hands, would you not do all in your power to restore them to happiness and liberty?’

But the young man’s appeal only stirred the two ladies to anger. ‘What,’ exclaimed one, ‘are the sorrows of lovers to us? Fate has deprived us of our lovers, and if it depends on us the whole world shall suffer as much as we do!’

This unexpected reply was heard with amazement by all present, and the Bassa entreated the speaker to tell them her story. Having obtained permission of her sister, she began: