The Lincoln–Douglas debates of 1858/Chapter 1

CHAPTER I

LINCOLN AND DOUGLAS

STUMP SPEAKING

The pioneers, who migrated with their families during the first half of the nineteenth century from the Atlantic Coast Plain to the Mississippi Valley found themselves cut off from the conveniences of life to which they had been accustomed, and cast into a compelling environment, where makeshifts and substitutes must answer for well-known utilities and contrivances. This was noticeable even in political campaigns. Lacking printing presses to disseminate party doctrines and public halls of sufficient size to accommodate the crowds at a party rally, the people of the frontier were wont to gather in some public square or in a grove of trees, where a temporary stand, or perhaps in very early days, the stump of a felled tree, answered the purpose of a rostrum from which the issues of the day were discussed by "stump" speakers. In the same way, the lack of churches on the frontier caused the substitution of groves as a place for holding "camp-meetings." Through campaign after campaign, both national and state, "stump" speaking continued until improved facilities for making longer journeys began to remedy western isolation and to remove western provincialism. At the same time, the increasing political activity of the printing press and the demands of modern business life gradually turned the people away from these picturesque gatherings of earlier times. Beginning with the campaign of 1824, in which a favorite son of Kentucky and a war-hero of Tennessee were championed in song and speech by their supporters in the Middle West, the political "stump" became the favorite hustings. The news that a leader was to "take the stump" in a certain district was sufficient promise of enlightenment on the political issues of the day in a region where newspapers and campaign literature were meager; and also the occasion was likely to afford a diversion in the way of rival processions and to furnish an opportunity of meeting one's friends and neighbors. The community which was favored as the scene of a political debate immediately awoke to unwonted activity. Banners were painted, flags flung from staff and building, and lithographs of rival candidates displayed in windows. Great barges or wagons, especially decorated for the occasion, were filled with "first voters," or with young women dressed to symbolize the political aspects of the campaign. Local merchants hurriedly stocked up on novelties likely to be in demand, while itinerant venders altered their schedules and hurried to the promising center of trade. Upon the public square each party erected a "pole" with a banner bearing the name of its candidates flying from the lofty top. The rural male voter did not appropriate to himself all the joys of the occasion, but the entire family "went to town," to enjoy the unusual day of diversion in the round of a monotonous and isolated life. A reporter connected with a New York newspaper was sent to Illinois to write up one of these "stump" campaigns, and both vividly and appreciatively he described the gathering of the people for the chief event of the summer:

"It is astonishing how deep an interest in politics this people take. Over long weary miles of hot and dusty prairie the processions of eager partisans come — on foot, on horseback, in wagons drawn by horses or mules; men, women, and children, old and young; the half sick, just out of the last 'shake;' children in arms, infants at the maternal fount, pushing on in clouds of dust and beneath the blazing sun; settling down at the town where the meeting is, with hardly a chance for sitting, and even less opportunity for eating, waiting in anxious groups for hours at the places of speaking, talking, discussing, litigious, vociferous, while the war artillery, the music of the bands, the waving of banners, the huzzahs of the crowds, as delegation after delegation appears; the cry of the peddlers vending all sorts of ware, from an infalliable cure of 'agur' to a monster watermelon in slices to suit purchasers—combine to render the occasion one scene of confusion and commotion. The hour of one arrives and a perfect rush is made for the grounds; a column of dust is rising to the heavens and fairly deluging those who are hurrying on through it. Then the speakers come with flags, and banners, and music, surrounded by cheering partisans. Their arrival at the ground and immediate approach to the stand is the signal for shouts that rend the heavens. They are introduced to the audience amidst prolonged and enthusiastic cheers; they are interrupted by frequent applause; and they sit down finally amid the same uproarious demonstration. The audience sit or stand patiently throughout, and, as the last word is spoken, make a break for their homes, first hunting up lost members of their families, getting their scattered wagonloads together, and, as the daylight fades away, entering again upon the broad prairies and slowly picking their way back to the place of beginning."— Special correspondence from Charleston, Illinois, to the New York Post, September 24, 1858.

The patience of the crowd in listening to lengthy speeches, as noted by this correspondent, finds many illustrations elsewhere. Three hours was the usual time allotted to a speaker. Sometimes after listening to a discussion of this length during the afternoon, the crowd would disperse for supper and then return to hear another speaker for an equal length of time during the evening. The spirit of fairness to both sides prompted the people to furnish one speaker with as large an audience as the other enjoyed. This spirit was manifested at Peoria in 1854 as the following extract from a contemporary newspaper shows:

"On Monday, October 16, Senator Douglas, by appointment, addressed a large audience at Peoria. When he closed he was greeted with six hearty cheers; and the band in attendance played a stirring air. The crowd then began to call for Lincoln, who, as Judge Douglas had announced, was, by agreement, to answer him. Mr. Lincoln then took the stand, and said—

"'I do not arise to speak now, if I can stipulate with the audience to meet me here at half past six or at seven o'clock. It is now several minutes past five, and Judge Douglas has spoken over three hours. If you hear me at all, I wish you to hear me thro'. It will take me as long as it has taken him. That will carry us beyond eight o'clock at night. Now every one of you who can remain that long, can just as well get his supper, meet me at seven, and remain one hour or two later. The judge has already informed you that he is to have an hour to reply to me. I doubt not but you have been a little surprised to learn that I have consented to give one of his high reputation and known ability this advantage of me. Indeed, my consenting to it, though reluctant, was not wholly unselfish; for I suspected if it were understood, that the Judge was entirely done, you democrats would leave, and not hear me; but by giving him the close, I felt confident that you would stay for the fun of hearing him skin me.'

"The audience signified their assent to the arrangement, and adjourned to 7 o'clock p. m., at which time they re-assembled, and Mr. Lincoln spoke."—Correspondence of the Illinois Journal, Springfield, October 21, 1854.

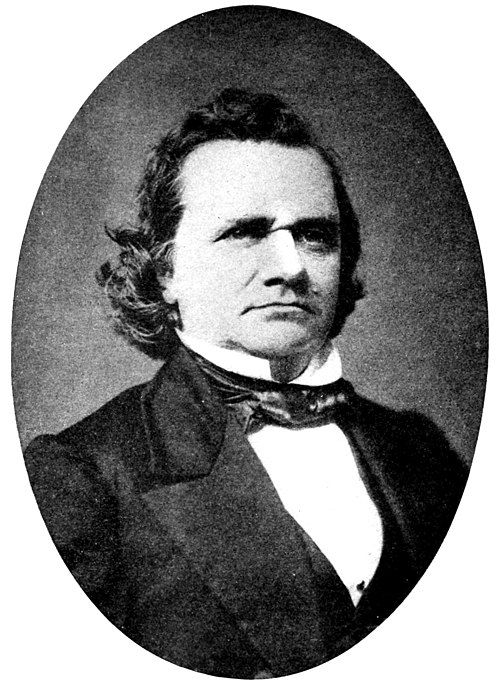

SENATOR DOUGLAS OF ILLINOIS

The storm center of political agitation, carried to the west of the Alleghany Mountains in the campaign of 1824, gradually advanced with the spread of the people, until the decade between 1850 and 1860 saw it centered in Illinois, mainly through the prominence of Senator Stephen A. Douglas and the Kansas-Nebraska question. As chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories, Douglas fathered and pushed to enactment the famous law of 1854, which repealed the Missouri Compromise so far at it related to the unorganized portion of the Louisiana Purchase lying north of 36° 30', and threw it open

to slavery or freedom as the future inhabitants might

STEPHEN A. DOUGLAS.

From a photograph in the collection of the Illinois Historical Library, supposed to have been made in 1858.

determine under the principle of home rule or "popular sovereignty." By this course he brought upon himself the denunciation and abuse of all northern people who opposed the further extension of slave territory.

Immediately upon the adjournment of Congress in August, 1854, Douglas started for Illinois to defend himself before his constituents. Before leaving Washington, he said: "I shall be assailed by demagogues and fanatics there, without stint or moderation. Every opprobrious epithet will be applied to me. I shall probably be hung in effigy in many places. This proceeding may end my political career. But, acting under the sense of duty which animates me, I am prepared to make the sacrifice." He reached Chicago September 2d, and took the rostrum in his own defense at a meeting which he caused to be announced for the following evening. The result may be learned from the newspapers of the day, by reading extracts from writers both favorable and hostile to him.

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, September 8, 1854]

The Chicago Tribune mentions the following among the occurrences of Friday afternoon:

The flags of all the shipping in port were displayed at half-mast, shortly after noon and remained there during the remainder of the day. At a quarter past six the bells of the city commenced to toll, and commenced to fill the air with their mournful tones for more than an hour. The city wore an air of mourning for the disgrace which her senator was seeking to impose upon her, and which her citizens have determined to resent at any cost.

[Chicago Times, September 4, 1854]

THE MEETING LAST NIGHT

During the whole of yesterday, the expected meeting of last night was the universal topic of conversation. Crowds of visitors arrived by the special trains from the surrounding cities and towns, even from as far as Detroit and St. Louis, attracted by the announcement that Judge Douglas was to address his constituents. In consequence of the extreme heat of the weather, it was deemed advisable to hold the meeting on the outside of the hall instead of the inside as had been announced.

At early candle light, a throng of 8,000 persons had assembled at the south part of the North Market Hall.

At the time announced, the Mayor of Chicago called the assemblage to order and Judge Douglas then addressed the meeting. . . . . He was frequently interrupted by the gang of abolition rowdies. . . . . Whenever he approached the subject of the Nebraska bill, an evidently well organized and drilled body of men, comprising about one-twentieth of the meeting, collected and formed into a compact body, refused to allow him to proceed. They kept up this disgraceful proceeding until after ten o'clock.

In vain did the mayor of the city appeal to their sense of order. They refused to let him be heard. Judge Douglas, notwithstanding the uproars of these hirelings, proceeded at intervals.

He told them he was not unprepared for their conduct. He had a day or two since received a letter written by the secretary of an organization framed since his arrival in the city for the purpose of preventing him from speaking. This organization required that he should leave the city or keep silent; and if he disregarded this notice, the organization was pledged at the sacrifice of his life to prevent his being heard. He presented himself, he said, and challenged the armed gang to execute on him their murderous pledge. The letter having been but imperfectly heard, its reading was asked by some of the orderly citizens present, but the mob refused to let it be heard, when Judge Douglas at the earnest request of some of his friends, left the stand.

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, September 4, 1854]

"THE DOUGLAS SPEECH"

This grand affair came off Friday night.—The St. Louis Republican had made one grand flourish in favor of the immortal Douglas by means of its correspondent, that Douglas would achieve wonders at Chicago and be sustained by the State. Office-holders far and near appeared at Chicago to enjoy his triumph. The evening came, and—we will let the Democratic Press speak—

Mr. Douglas had a stormy meeting last evening at the North Market Hall. There was a great amount of groans and cheers. But there was nothing like a riot or any approach to it.

He said some bitter things against the press of Chicago, and did not compliment the intelligence of citizens in very pleasant terms. They refused to hear him on these subjects. Towards the close of his speech they became so uproarious that he was obliged to desist.

The plain truth is there were a great many there who were unwilling to hear him and manifested their disapprobation in a very noisy and disrespectful manner. We regret exceedingly that he was not permitted to make his speech unmolested. That would have been far better than the course that was pursued.

We are glad however, that when he decided to make no further efforts the people retired peaceably to their homes and all was quiet.

The Chicago Democrat disposes of the matter even in fewer words:

Senator Douglas.—Last evening a large number of citizens assembled in front of the North Market Hall, some to listen to Senator Douglas' remarks on the act known as the Nebraska Act, and some with the express purpose of preventing his making any remarks. The meeting was called to order, and Senator Douglas was introduced to the audience by Mayor Milliken. The noise and disturbance of the audience was such, however, that he was unable to pursue his argument in a manner satisfactory to those who wished to learn what he would say in vindication of his course.

We have heard from private sources that there were ten thousand people present; and that evidently they did not come there to get up a disturbance but simply to demonstrate to Sen. Douglas their opinion of his treachery to his constituents. This they did effectually; and Mr. Douglas now fully understands the estimate in which his conduct is held by his townsmen at Chicago.

It is said that Mr. Douglas felt, intensely, the rebuke he had received.

The office-holders who went to Chicago from here and elsewhere are very quiet on their return, and have learnt something of public opinion in the north part of the state.

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, September 5, 1854]

SPEECH OF SENATOR DOUGLAS

At the North Market Hall on Friday Evening, September 1st. 1854

You have been told that the bill legislated slavery into territory now free. It does no such thing. [Groans and hisses — with abortive efforts to cheer.] As most of you have never read that bill [Groans], I will read to you the fourteenth section. [Here he read the section referred to, long since published and commented on in this paper.] It will be seen that the bill leaves the people perfectly free. [Groans and some cheers.] It is perfectly natural for those who have misrepresented and slandered me, to be unwilling to hear me. I am here in my own home. [Tremendous groans—a voice, that is in North Carolina—in Alabama, &c.,—go there and talk, &c.—]

I am in my own home, and have lived in Illinois long before you thought of the State. I know my rights, and, though personal violence has been threatened me, I am determined to maintain them. ["Much noise and confusion."] The principle of the Nebraska bill grants to the people of the territories the right to govern themselves. Who dares deny that right [a voice, It grants the right to take slavery there that's all]. What is the Missouri Compromise line? It was simply a line, recognizing slavery on one side of it and forbidding it on the other. Now would any of you permit the establishment of slavery on either side of any line? [No! No!!]

Mr. Douglas said he would show that all of his audience were in 1S4S in favor of the repeal of the Missouri Compromise and he alone was opposed to it. [Three cheers were given for the Compromise.]

The compromise measures of 1850 were endorsed by our own city Council. They were also endorsed by our legislature almost unanimously. The resolution passed by our Legislature in 1851, approved of the principles of non-intervention—[it was published in the Press, with comments a few days since], in the most direct and strongest terms. All the Representatives except four whigs voted for the resolution.—Every representative from Cook county voted for them.

These were the instructions under which he acted. Till then he was the fast friend of the Compromise. [A voice—then why did you repeal it?] Simply because another principle had been adopted and I acted upon that principle.—[Some one asked that if he lived in Kansas whether he would vote for its being a free State.—But the Senator could not find it convenient to answer it, though repeated several times.]

The question now became more frequent and the people more noisy. Judge Douglas became excited, and said many things not very creditable to his position and character. The people as a consequence refused to hear him further, and although he kept the stand for a considerable time he was obliged at last to give way and retire to his lodgings at the Tremont House. The people then separated quietly and all except the office-holders, in the greatest of good humor.—

A large number, and we certainly were among them, felt deeply mortified that Mr. Douglas had not been permitted to say what he pleased. We must say, however, that the matter terminated much more peacefully than most of our citizens feared, and all have reason, considering the excited state of public mind, to be thankful that matters are no worse.

ABRAHAM LINCOLN OF ILLINOIS

Among those who opposed the action of Douglas was his long-time friend and rival, Abraham Lincoln, who had served several terms in the Illinois State Legislature and one term in Congress (1847-49) and then retired from public life to look after his law practice. After six years of retirement, he confessed himself drawn again into the arena of politics by the passing of the Kansas-Nebraska act. In the dissatisfaction with Douglas and the Democratic dissension likely to follow, Lincoln saw an opportunity for the Whigs of Illinois and an opening for his long-suppressed political ambitions. During the autumn of 1854, after Douglas had been refused a hearing in Chicago, Lincoln wrote to an influential friend, "It has come around that a Whig may by possibility be elected to the United States Senate, and I want the chance of being that man."[1]

At this time, Lincoln was among the most prominent of the old line Whigs of Illinois; but the dissensions in the Democratic party which promised him a hearing also brought an obstacle in the many prominent Democrats who were deserting the pro-slavery Douglas and who might properly be called new line Whigs, although known as anti-Nebraska men. The Whigs, never able to carry the state, welcomed an alliance with these seceders on the common basis of opposition to slavery extension; naturally a greater public interest would attach to them than to a regular Whig like Lincoln; and the latter was in danger of being relegated to second place during the important Springfield Fair week of 1854.

[Altoti, Illinois, Courier, October 27, 1854]

Heretofore the Democracy of Central and Southern Illinois, who disagree with Judge Douglas on the Nebraskan measure, have been almost entirely silent in regard to it, and Judge Douglas and his supporters in the matter have had matters entirely their own way. . . . This state of things, as every one must have foreseen, could not last long. The democracy have been aroused and Judge Douglas is to be met at Springfield by several of the first minds of the State, men who would honor any State or nation and no less giants than himself. We are informed that Judge Trumbull, Judge Breese, Col. McClernand Judge Palmer, Col. E. D. Taylor, and others will be there and reply to Judge Douglas. He will find as foemen tried Democrats, lovers of the Baltimore platform and opposed to all slavery agitation—giants in intellect, worthy of his steel.

THE DEBATES OF 1854

The Illinois State Agricultural Fair held annually at Springfield was the culminating political event of the year—a characteristic which it bears to the present day. This gathering, devoted primarily to the interests of the farmer, became a rendezvous for state politicians, where plans were laid, candidates brought out, and the issues of the day discussed by the ablest speakers in each party. Douglas well knew that he must defend himself against the Whigs and also against many former supporters in his own party, as indicated in the quotation above. Leaving Chicago after failing to secure a hearing, Douglas went to Indianapolis and then returned to Illinois, addressing enthusiastic meetings at Ottawa, Joliet, Rock Island, and other places before the first week in October, which was the date of the State Fair. Springfield at this time contained about fifteen thousand inhabitants and the visitors to the fair increased the population at least ten thousand. It was the day of stump speaking. The farmers held sessions daily during the week at which they discussed topics pertaining to agriculture and its allied interests; each evening a woman was lecturing in the court room on "Woman's Influence in the Great Progressive Movements of the Day;" and the politicians occupied the senate chamber from noon to midnight with a short intermission for supper. In a card given out through the press, the members of the Agricultural Society protested against the political speakers taking advantage of their "Annual Jubilee and School of Life" to occupy the time and distract the attention of the people by a public discussion of questions foreign to the objects of the society. "The politicians as well as the farmers are out in force," wrote a reporter.

On Wednesday of Fair week, Douglas spoke in the Hall of Representatives in the State House, making a masterly defense of himself and his theory of popular sovereignty. He was to be answered at the same place the following afternoon by Judge Trumbull, of Alton, the most prominent anti-Nebraska Democrat in the southern part of the state. Trumbull failed to arrive at the proper time and Abraham Lincoln, a Whig, arose to reply to Douglas. Lincoln was the recognized speaker for the Whigs in Springfield: a month before, he had replied to Calhoun, a pro-Nebraska Democrat.

[Chicago Democratic Press, October 6, 1854]

POLITICAL SPEAKING

Today we listened to a 31⁄2 hour's speech from the Hon. Abram Lincoln, in reply to that of Judge Douglas of yesterday. He made a full and convincing reply and showed up squatter sovereignty in all its unblushing pretensions. We came away as Judge Douglas commenced to reply to Mr. Lincoln.

LINCOLN AT THE STATE FAIR

My acquaintance with Mr. Lincoln began in October, 1854.[2] I was then in the employ of the Chicago Evening Journal. I had been sent to Springfield to report the political doings of State Fair week for that newspaper. Thus it came about that I occupied a front seat in the Representatives' Hall, in the old State House when Mr. Lincoln delivered a speech already described in this volume. The impression made upon me by the orator was quite overpowering. I had not heard much political speaking up to that time. I have heard a great deal since. I have never heard anything since, either by Mr. Lincoln, or by anybody, that I would put on a higher plane of oratory. All the strings that play upon the human heart and understanding were touched with masterly skill and force, while beyond and above all skill was the overwhelming conviction pressed upon the audience that the speaker himself was charged with an irresistible and inspiring duty to his fellowmen. . . . .

Although I heard him many times afterward, I shall longest remember him as I then saw the tall, angular form with the long, angular arms, at times bent nearly double with excitement, like a large flail animating two smaller ones, the mobile face wet with perspiration which he discharged in drops as he threw his head this way and that like a projectile—not a graceful figure and yet not an ungraceful one.

Lincoln spoke until half-past five; Douglas replied for an hour and then announced that he would leave off to enable the listeners to have their suppers and would resume at early candle light. But when that time arrived, Douglas for some reason failed to resume, other speakers took the platform, and Douglas' "unfinished speech" was the cause of endless raillery on the part of the Whigs who claimed that he found Lincoln's arguments unanswerable. The style of argument of each was known to the other because they had debated public questions in Springfield as early as seventeen years before. Trumbull arrived in time to speak on Thursday evening and his speech was widely copied in the press of the state as representative anti-Nebraska doctrine. Lincoln, through the influence of his friend Herndon, was given extravagant praise in the Journal of Springfield, but his speech created no widespread comment throughout the state such as Herndon would have us believe.[3]

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, October 5, 1854]

HON. A. LINCOLN'S SPEECH

Agreeably to previous notice, circulated in the morning by hand bill, Hon. A. Lincoln delivered a speech yesterday, at the State House, in the Hall of Representatives in reply to the speech of Senator Douglas, of the preceding day. Mr. L. commenced at 2 o'clock, p. m., and spoke above three hours, to a very large, intelligent and attentive audience. Judge Douglas had been invited by Mr. Lincoln to be present and to reply to Mr. Lincoln's remarks, if he should think proper to do so. And Judge Douglas was present, and heard Mr. Lincoln throughout.

Mr. Lincoln closed amid immense cheers. He had nobly and triumphantly sustained the cause of a free people, and won a place in their hearts as a bold and powerful champion of equal rights for American citizens, that will in all time be a monument to his honor. Mr. Douglas replied to Mr. Lincoln, in a speech of about two hours. It was adroit, and plausible, but had not the marble of logic in it.

[Illinois Journal, Springfield October 10, 1854]

LINCOLN AND DOUGLAS

The debate between these two men came off in the State House on the fifth of October. The Hall of the House of Representatives in which the speaking was heard, was crowded to overflowing. The number present was about two thousand, Mr. Lincoln commenced at 2 o'clock p. m., and spoke three hours and ten minutes.

We propose to give our views and those of many northerners and many southerners upon the debate. We intend to give it as fairly as we can. Those who know Mr. Lincoln, know him to be a conscientious and honest man, who makes no assertions that he does not know to be true.

It was a proud day for Lincoln. His friends will never forget it. The news had gone abroad that "Lincoln was afraid to meet Douglas;" but when he arose, his manly and fearless form shut up and crushed out the charge. We will not soon forget his appearance as he bowed to the audience, and looked over the vast sea of human heads.

Douglas arose and commenced his answers to Mr. Lincoln—and his eloquence can only be compared to his person—false and brusque. He is haughty and imperative,—his voice somewhat shrill and his manner positive;—now flattering, now wild with excess of madness That trembling fore-finger, like a lash, was his whip to drive the doubting into the ranks. He is a very tyrant.—

When he arose he most evidently was angry for being bearded in the Capitol, and if we judge not wrongly, we affirm that he is conscious of his ruin and doom. The marks and evidences of desolation are furrowed in his face, — written on his brow.

Lincoln next followed Douglas to Peoria and replied to him at that point, October 16, 1854.[4] A fortnight later elections were held for members of the state legislature who would choose in joint session a fellow-senator for Douglas from Illinois.

SENATORIAL ELECTION OF 1854

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, February 9, 1855]

SENATORIAL ELECTION

Trumbull Elected—The Anti-Nebraska Sentiment of Illinois Vindicated

The Senatorial election took place on yesterday. . . . . Abraham Lincoln had by far the largest number of votes on the first votes [ballot]: but it having become apparent that he could not be elected, his friends to a man, with his entire approbation, united on a candidate that could be, and was, elected. Every vote Judge Trumbull received came from anti-Nebraska and anti-Douglas men. Thus has the State of Illinois rebuked the authors of the repeal of the Missouri restriction.—They have done it in a manner that will be felt, not only in this State, but throughout the nation. The Douglas party would have greatly preferred the election of Lincoln, Williams, Odgen, Kellogg, or Sweet, to that of Judge Trumbull. They were most anxious to crush him for daring to be honest.

Of Mr. Lincoln, we need scarcely say,—that though ambitious of the office himself,—when it was apparent that he could not be elected, he pressed his friends to vote for Mr. Trumbull.—Mr. Lincoln's friends can well say, that while with his advice they ultimately cast their votes for, and assisted in the election of Mr. Trumbull, it was not "because they loved Ceasar less, but because they loved Rome more."

It has long been certain that there was an anti-Nebraska majority in the Legislature. The Douglas men were certain of this fact—and their anticipated "triumph," as announced by Mr. Moulton in the House, was based on the known popularity of Gov. Matteson personally, which would give their votes for him and which would ensure his election.

Although Herndon and Lincoln's other friends attempted in these complimentary terms to soften the blow of his defeat, he felt keenly the sacrifice he had been compelled to make for a man who had been until recently his political enemy, "I regret my defeat moderately," he wrote to a friend, "but am not nervous about it."[5] Quite naturally he would be given a chance when the next senatorial vacancy occurred and that would be four years hence.

PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION OF 1856

As the presidential year of 1856 came on, the old line Whigs and anti-Nebraska men were fused into the new Republican party through spontaneous conventions held in the different northern states. In Illinois, "People's" conventions assembled in the counties and named delegates to a state convention which was held in Bloomington in May, representing "those regardless of party who oppose the further extension of slave territory and who wish to curb the rising pretentions of the slave oligarchy." Among the prominent men present was Abraham Lincoln, who spoke at the close of the convention. Reporters afterward testified that the spell of his simple oratory was so entrancing that they forgot their tasks and the speech went unreported. In later years it was written out from memory by one of the hearers and became known as "Lincoln's lost speech," being the subject of no little controversy.

[Illinois Journal, Springfield, June 3, 1856]

HON. A. LINCOLN

During the recent session of the State anti-Nebraska Convention, the Hon. A. Lincoln of this city made one of the most powerful and convincing speeches which we have ever heard. The editor of the Chicago Press, thus characterizes it:

Abram Lincoln of Springfield was next called out, and made the speech of the occasion. Never has it been our fortune to listen to a more eloquent and masterly presentation of a subject. I shall not mar any of its fine proportions or brilliant passages by attempting even a synopsis of it. Mr. Lincoln must write it out and let it go before all the people. For an hour and a half he held the assemblage spell-bound by the power of his argument, the intense irony of his invective, and the deep earnestness and fervid brilliancy of his eloquence. When he concluded, the audience sprang to their feet, and cheer after cheer told how deeply their hearts had been touched, and their souls warmed up to a generous enthusiasm.

In the Democratic national convention which met at Cincinnati, June 2, 1856, Douglas on one ballot received 121 votes, but the nomination eventually went to James Buchanan. In the Republican national convention, which met at Philadelphia, two weeks later, Lincoln was given 110 votes on the informal vote for the vice-presidency, but Dayton was nominated. Lincoln headed the list of Illinois electors for Fremont and Dayton. During the campaign, Douglas took the stump for Buchanan and Lincoln for Fremont. After the defeat of Fremont, Lincoln said in a speech at a banquet in Chicago: "In the late contest we were divided between Fremont and Buchanan. Can we not come together in the future? Let bygones be bygones; let past differences be as nothing; and with steady eye on the real issue, let us re-inaugurate the good old 'central ideas' of the republic. We can do it. The human heart is with us; God is with us."

In June, of the following year, 1857, Douglas spoke in Springfield on current political topics and two weeks later Lincoln answered him at the same place.

- ↑ Nicolay and Hay, Complete Works of Abraham Lincoln, I, 209

- ↑ Mr. Horace White in Herndon's Life of Lincoln, by permission of D. Appleton & Co.

- ↑ "At this time I was zealously interested in the new movement, and not less so than in Lincoln. I frequently wrote the editorials in the Springfield Journal......Many of the editorials I wrote were intended directly or indirectly to promote the interests of Lincoln."—Herndon's Life of Lincoln, II, 36, 38.

- ↑ Nicolay and Hay, Complete Works, I, 180.

- ↑ Nicolay and Hay, op.cit., 215.