The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy (1729)/Book 1/Section 4

Section IV.

Of the finding of elliptic, parabolic, and hyperbolic orbits, from the focus given.

Lemma XV.

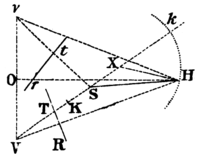

If from the two foci S, H, (Pl. 7. Fig, 1.) of any ellipisis or hyperbola, we draw to any third point V the right lines SV, HV, whereof one HV is equal to the principal axis of the figure, that is, to the axis in which the foci are situated, the other SV is bisected in T by the perpendicular TR let fall upon it; that perpendicular TR will somewhere touch the conic section: and vice versa if it does touch it, HV will be equal to the principal axis of the figure.

For, let the perpendicular TR cut the right line HV, produced if need be, in R; and join SR. Because RS, TV are equal, therefore the right lines SR, VR, as well as the angles TRS, TRV, will be also equal. Whence the point R will be in the conic section, and the perpendicular TR will touch the same: and the contrary. Q. E. D.

Proposition XVIII. Problem X.

From a focus and the principal axes given, to describe elliptic and hyperbolic trajectories, which shall pass through given points, and touch right lines given by position. Pl. 7. Fig. 2.

Let S be the common focus of the figures; AB the length of the principal axis of any trajectory; P a point through which the trajectory should pass; and TR a right line which it should touch. About the centre P, with the interval AB - SP, if the orbit is an ellipsis, or AB + SP if the orbit is an hyperbola, describe the circle HG. On the tangent TR let fall the perpendicular ST and produce the same to V, so that TV may be equal to ST; and about V as a centre with the interval AB describe the circle FH. In this manner whether two points P, p, are given, or two tangents TR, tr, or a point P and a tangent TR, we are to describe two circles. Let H be their common intersection, and from the foci S, H with the given axis describe the trajectory. I say the thing is done. For (because PH + SP in the ellipsis, and PH - SP in the hyperbola is equal to the axis) the described trajectory will pass through the point P, and (by the preceding lemma) will touch the right line TR. And by the same argument it will either pass through the two points P, p, or touch the two right lines TR, tr. Q. E. F.

Proposition XIX. Problem XI.

About a given focus, to describe parabolic trajectory, which shall pass through given points, and touch right lines given by position. Pl. 7. Fig. 3.

Let S the the focus, P a point, and TR a tangent

of the trajectory to be described. About P as a centre,

with the interval PS, describe the circle FG;

From the focus let fall ST perpendicular on the tangent,

and produce the same to V, so as TV may be equal

to ST. After the same manner another circle

fg is to be described, if another point p is given; or

another point v is to be found, if another tangent tr

is given; then draw the right line IF, which shall

touch the two circles FG, fg, if two points P, p

are given, or pass through the two points V, v,

if two tangents TR, tr are given, or touch the

circle FG and pass through the point V, if the point P

and the tangent TR are given. On FI let fall the

perpendicular SL and bisect the same in K; and with

the axis SK, and principal vertex K describe a parabola.

I say the thing is done. For this parabola (because

SK is equal to IK, and SP to FP) will pass through

the point P; and (by cor. 3. lem. 14.) because ST is

equal to TV and STR; a right angle, it will touch the

right line TR. Q. E. F.

Proposition XX. Problem XII.

About a given focus to describe any trajectory given in specie, which shall pass thro' given points and touch right lines given by position.

Case 1. About the focus (Pl. 7. Fig. 4.) it is required to describe trajectory ABC, passing thro' two points B, C. Because the trajectory is given in specie, the ratio of the principal axe to the distance of the foci will be given. In that ratio take KB to BS and LC to CS. About the centres B, C, with the intervals BK. CL describe two circles, and on the right line KL, that touches the same in K and L, let fall the perpendicular SG; which cut in A and a, so that GA may be to AS, and Ga to aS, as KB to BS; and with the axe Aa, and vertices A, a, describe a trajectory. I say the thing is done. For let H be the other focus of the described figure, and seeing GA is to AS as Ga to aS, then by division we shall have Ga - GA or Aa to aS - AS or SH in the same ratio, and therefore in the ratio which the principal axe of the figure to be described has to the distance of its foci; and therefore the described figure is of the same species with the figure which was to be described. And since KB to BS, and LC to CS are in the same ratio, this figure will pass thro' the points B, C, as is manifest from the conic sections

Case 2. About the focus (Pl. 7. Fig. 5.) it is required to describe a trajectory, which shall somewhere touch two right lines TR, tr. From the focus On those tangents let fall the perpendiculars ST, St, which produce to V, v, so that TV, tv may be equal to TS, tS. Bifect Vv in O, and erect the indefinite perpendicular OH, and cut the right Line VS infinitely produced in K and k, so that VK be to KS, and Vk to kS as the principal axe of the trajectory to be described is to the distance of it's foci. On the diameter Kk describe a circle cutting OH in H; and with the foci S, H, and principal axe equal to VH, describe a trajectory. I say the thing is done. For, bisecting Kk in X, and joining HX, HS, HV, Hv, because VK is to KS, as Vk to kS; and by composition, as Vk + Vk to KS + kS; and by division as Vk - VK to kS - KS that is, as 2VX to 2KX and 2KX to 2SX, and therefore as VX to HX and HX to SX the triangles VXH, HXS will be similar; Therefore VH will be to SH, as VX to XH; and therefore as VK to KS. Wherefore VH the principal axe of the described trajectory has the same ratio to SH the distance of the foci, as the principal axe of the trajectory which was to be described has to the distance of its foci; and is therefore of the same species. And seeing VH, vH, are equal to the principal axe, and VS, vS are perpendicularly bisected by the right lines TR, tr; 'tis evident (by lem. 15.) that those right lines touch the described trajectory. Q. E. F.

Case 3.. About the focus S (Pl. 7. Fig. 6.) it is required to describe a trajectory, which shall touch a right line TR in a given point R. On the right line TR let fall the perpendicular ST; which produce to K so that TV maybe equal to ST, join VR, and cut the right line VS indefinitely produced in K and k, so that VK may be to SK, and Vk to Sk as the principal axe of the ellipsis to be described, to the distance of itsfoci; and on the diameter Kk describing a circle, cut the right line VR produced in H, then with the foci S, H and principal axe equal to VH, describe trajectory. I say the thing is done. For VH is to SH as VK to SK, and therefore as the principal axe of the trajectory which was to be described to the distance of its foci, (as appears from what we have demonstrated in Case 1.) and therefore the described trajectory is of the same species with that which was to be described; but that right line TR, by which the angle VRS is bisected, touches the trajectory in the point R, is certain from the properties of the conic sections. Q. E. F.

Case 4. About the focus S (Pl. 7. Fig. 7.) it is required to describe a trajectory APB that shall touch a right line TR. and pass thro' any given point P without the tangent, and shall be similar to the figure apb, described with the principal axe ab, and foci s, h. On the tangent TR let fill the perpendicular ST; which produce to V, so that TV may be equal to ST. And making the angles hsq, shq equal to the angles VSP, SVP; about q as a centre, and with an interval which shall be to ab as SP to VS describe a circle cutting the figure apb in p: join sp, and draw SH, such that it may be to sh, as SP is to sp, and may make the angle PSH equal to the angle psh; and the angle VSH equal to the angle psq. Then with the foci S, H, and principal axe AB equal to the distance VH, describe a conic section. I say the thing is done. For if sv is drawn so that it shall be to sp as sh is to sq, and shall make the angle vsp equal to the angle hsq, and the angle vsh equal to the angle psq, the triangles svh, spq, will be similar, and therefore vh will be to pq, as sh is to sq, that is, (because of the similar triangles VSP, hsq) as VS is to SP or as ab to pq. Wherefore vh and ab are equal. But because of the similar triangles VSH, vsh, VH is to SH as vh to sh; that is, the axe of the conic section now described is to the distance of its foci, as the axe ab to the distance of the foci s, h; and therefore the figure now described is similar to the figure aph. But, because the triangle PSH is similar to the triangle psh, this figure passes through the point P, and because VH is equal to its axis, and VS is perpendicularly bisected by the right line TR, the said figure touches the right line TR. Q. E. F.

Lemma XVI.

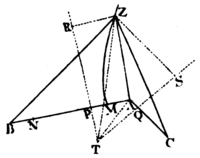

From three given point: to draw to a fourth point that is not given three right lines whose differences shall be either given or none at all.

Case 1.. Let the given points be A, B, C (Pl. 8. Fig. 1.) and Z the fourth point which we are to find; because of the given difference of the lines AZ, BZ, the locus of the point Z will be an hyperbola. whose foci are A and B, and whose principal axe is the given difference. Let that axe be MMN. Taking PM to MA, as MN is to AB, erect PR perpendicular to AB, and let all ZR perpendicular to PR; then, from the nature of the hyperbola, ZR will be to AZ as MN is to AB. And by the like argument, the locus of the point Z will be another hyperbola, whose foci are A, C, and whose principal axe is the difference between AZ and CZ; and QS a perpendicular on AC may be drawm to which (QS) if from any point Z of this hyperbola a perpendicular ZS is let fall, this (ZS) shall be to AZ as the difference between AZ and CZ is to AC. Wherefore the ratio's of ZR and ZS to AZ are given, and consequently the ratio of ZR to ZS one to the other; and therefore if the right lines RP SQ meet in T, and TZ and TA are drawn, the figure TRZS will be given in specie, and the right line TZ, in which the point Z is somewhere placed, will be given in position. There will be given also the right line TA, and the angle ATZ; and because the ratio's of AZ and TZ to ZS are given, their ratio to each other is given also; and thence will be given likewise the triangle ATZ whose vertex is the point Z. Q. E. I.

Case 2. If two of the three lines, for example AZ and BZ, are equal, draw the right line TZ so as to bisect the right line AB; then find the triangle ATZ as above. Q. E. I.

Case 3. If all the three are equal, the point Z will be placed in the centre of a circle that passes thro' the points A, B, C. Q. E. I.

This problematic lemma is likewise solved in Apollonui's Book of Tactions restored by Victa.

Proposition XXI. Problem XIII.

About a give focus to describe a trajectory, that shall pass through given points and touch right lines given by position.

Let the focus S, (Pl. 8. Fig. 2.) the point P, and the tangent TR be given, suppose that the other focus H is to be found. On the tangent let fall the perpendicular ST, which produce to T, so that TY may be equal to ST; and YH will be equal to the principal axe. Join SP, HP, and SP will be the difference between HP and the principal axe. After this manner if more tangents TR are given, or more points P, we shall always determine as many lines YH or PH, drawn from the said points T or P, to the focus H, which either shall be equal to the axes, or differ from the axes by given lengths SP; and therefore which shall either be equal among themselves, or shall have given differences; from whence (by the preceding lemma) that other focus H is But having the foci and the length of the axe (which is either TH; or, if the trajectory be an ellipsis, PH + SP, or PH - SP if it be an hyperbola) the trajectory is given. Q. E. I.

Scholium.

When the trajectory is an hyperbola, I do not comprehend its conjugate by hyperbola under the name of this trajectory. For a body going on with a continued motion can never pass out of one hyperbola into its conjugate hyperbola.

The case when three points are given is more readily solved thus. Let B, C, D (PL 8. Fig. 3.) be the given points. join BC, CD, and produce them to E, F; s as EB may be to EC, as SB to SC; and FC to FD, as SC to SD. On EF drawn and produced let fall the perpendiculars SG, BH and in GS produced indefinitely take GA to AS, and Ga to aS, as HB is to BS; then A will be the vertex, and Aa the principal axe of the trajectory: Which, according as GA is greater than, equal to, or less than AS, will be either an ellipsis, a parabola or an hyperbola; the point a in the first case falling on the same side of the line (GF as the point A; in the second, going off to an infinite distance; in the third, falling on the other side of the line GF. For if on GF, the perpendiculars Ct, DK are let fall, IC will be to HB as EC to EB; that is, as SC to SB; and by permutation IC to SC as HB to SB, or as GA to SA. And, by the like argument, we may prove that KD is to SD in the same ratio. Wherefore the points B, C, D lie in a conic section described about the focus S, in such manner that all the right lines drawn from the focus S to the several points of the section, and the perpendicular: let fall from the same points on the right line GF are in that given ratio.

That excellent geometer M. De la Hire has solved this problem much after the same way in his conics, prop. 25. lib. 8.