The Natural History of Selborne, 1879/Letter 16

LETTER XVI.

Selborne, April 18th, 1768.

Dear Sir, The history of the stone-curlew, Charadrius œdicnemus, is as follows. It lays its eggs, usually two, never more than three, on the bare ground, without any nest, in the field; so that the countryman, in stirring his fallows, often destroys them. The young run immediately from the egg like partridges, etc., and are withdrawn to some flinty field by the dam, where they skulk among the stones, which are their best security; for their feathers are so exactly of the colour of our grey spotted flints, that the most exact observer, unless he catches the eye of the young bird, may be eluded. The eggs are short and round; of a dirty white, spotted with dark bloody blotches. Though I might not be able, just when I pleased, to procure you a bird, yet I could show you them almost any day; and any evening you may hear them round the village, for they make a clamour which may be heard a mile. Oedicnemus is a most apt and expressive name for them, since their legs seem swoln like those of a gouty man. After harvest I have shot them before the pointers in turnip-fields.

Common Curlew.

I make no doubt but there are three species of the willow-wrens; two I know perfectly, but have not been able yet to procure the third.[e1] No two birds can differ more in their notes, and that constantly, than those two that I am acquainted with; for the one has a joyous, easy, laughing note, the other a harsh loud chirp. The former is every way larger, and three-quarters of an inch longer, and weighs two drams and a half, while the latter weighs but two; so the songster is one-fifth heavier than the chirper. The chirper (being the first summer-bird of passage that is heard, the wryneck sometimes excepted) begins his two notes in the middle of March, and continues them through the spring and summer till the end of August, as appears by my journals. The legs of the larger of these two are flesh-coloured; of the less black.

The Chiff-Chaff (Sylvia hippolais).

The grasshopper-lark began his sibilous note in my fields last Saturday. Nothing can be more amusing than the whisper of this little bird, which seems to be close by though at a hundred yards distance; and when close at your ear, is scarce any louder than when a great way off. Had I not been a little acquainted with insects, and known that the grasshopper kind is not yet hatched, I should have hardly believed but that it had been a locusta whispering in the bushes. The country people laugh when you tell them that it is the note of a bird. It is a most artful creature, sculking in the thickest part of a bush; and will sing at a yard distance, provided it be concealed. I was obliged to get a person to go on the other side of the hedge where it haunted, and then it would run, creeping like a mouse, before us for a hundred yards together, through the bottom of the thorns; yet it would not come into fair sight; but in a morning early, and when undisturbed, it sings on the top of a twig, gaping and shivering with its wings. Mr. Ray himself had no knowledge of this bird, but received his account from Mr. Johnson, who apparently confounds it with the reguli non cristati, from which it is very distinct. See Ray's "Philos. Letters," p. 108.

The fly-catcher (stoparola) has not yet appeared; it usually breeds in my vine. The redstart begins to sing, its note is short and imperfect, but is continued till about the middle of June. The willow-wrens (the smaller sort) are horrid pests in a garden, destroying the peas, cherries, currants, etc,; and are so tame that a gun will not scare them.

| LINNÆI NOMINA. | |

| Smallest willow-wren, | Motaclila trochilus. |

| Wryneck, | Jynx torquilla. |

| House-swallow, | Hirundo rustica. |

| Martin, | Hirundo urbica. |

| Sand-martin, | Hirundo riparia. |

| Cuckoo, | Cuculus canorus. |

| Nightingale, | Motacilla luscinia. |

| Blackcap, | Motacilla atricapilla. |

| Whitethroat, | Motacilla sylvia. |

| Middle willow-wren, | Motacilla trochilus. |

| Swift, | Hirundo apus. |

| Stone-curlew? | Charadrius œdicnemus? |

| Turtle-dove? | Turtur aldrovandi? |

| Grasshopper-lark, | Alauda trivialis. |

| Landrail, | Rallus crex. |

| Largest willow-wren, | Motacilla trochilus. |

| Redstart, | Motacilla phœnicurus. |

| Goat-sucker, or fern-owl, | Caprimulgus europæus. |

| Fly-catcher, | Muscicapa grisola. |

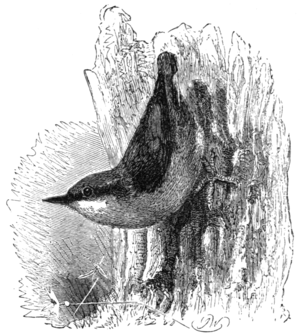

My countrymen talk much of a bird that makes a clatter with its bill against a dead bough, or some old pales, calling it a jar-bird. I procured one to be shot in the very fact; it proved to be the Sitta europæa (the nuthatch).[e2] Mr. Ray says that the less spotted woodpecker does the same. This noise may be heard a furlong or more.

Now is the only time to ascertain the short-winged summer birds; for, when the leaf is out, there is no making any remarks on such a restless tribe; and when once the young begin to appear it is all confusion: there is no distinction of genus, species, or sex.

Nuthatch.

In breeding-time snipes play over the moors, piping and humming; they always hum as they are descending. Is not their hum ventriloquous like that of the turkey? Some suspect it is made by their wings.

This morning I saw the golden-crowned wren, whose crown glitters like burnished gold.[e3] It often hangs like a titmouse, with its back downwards.

Yours, etc., etc.

notes to letter xvi.

e1 ↑ White probably means the willow-wren and chiff-chaff which are common, and the wood-wren which is rare.

e2 ↑ The nuthatch builds in holes in trees, and if the opening is too large, it builds it up with mud, leaving only sufficient room for its own egress and ingress.

e3 ↑ The golden-crested wren suspends its deep purse-like nest beneath some thick fir branch, and lays a number of tiny yellow-brown eggs, like green-peas in size. All the winter through this wren and the long-tailed tit frequented the hedgerows and coppices in Shropshire, and were frequent victims to a school-boy's love of chevying.