The Naturalist's Library/Bees

![]()

This work was published before January 1, 1930, and is in the public domain worldwide because the author died at least 100 years ago.

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

LIST OF VOLUMES

OF THE

NATURALIST'S LIBRARY,

IN THE ORDER IN WHICH THEY WERE PUBLISHED.

| I. | HUMMING-BIRDS, Thirty-six Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Linnæus.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| II. | MONKEYS, Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Buffon. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| III. | HUMMING-BIRDS, Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Pennant. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IV. | LIONS, TIGERS, &c., Thirty-eight Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Cuvier. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| V. | PEACOCKS, PHEASANTS, TURKEYS, &c.. Thirty Coloured Plates, with Portrait and Memoir of Aristotle. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VI. | BIRDS OF THE GAME KIND, Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VII. | FISHES OF THE PERCH GENUS, &c., Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Sir Joseph Banks. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| VIII. | COLEOPTEROUS INSECTS, (Beetles,) Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Ray. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| IX. | COLUMBIDÆ, (Pigeons,) Thirty-two Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Pliny. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| X. | BRITISH DIURNAL LEPIDOPTERA, (Butterflies,) Thirty-six Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Werner. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| XI. | RUMINATING ANIMALS; containing Deer, Antelopes, Camels, &c., Thirty-five Coloured Plates; with Portrait and Memoir of Camper. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| XII. | RUMINATING ANIMALS; containing Goats, Sheep, Wild and Domestic Cattle, &c. &c., Thirty-three Coloured Plates ; with Portrait and Memoir of John Hunter. </noinclude>

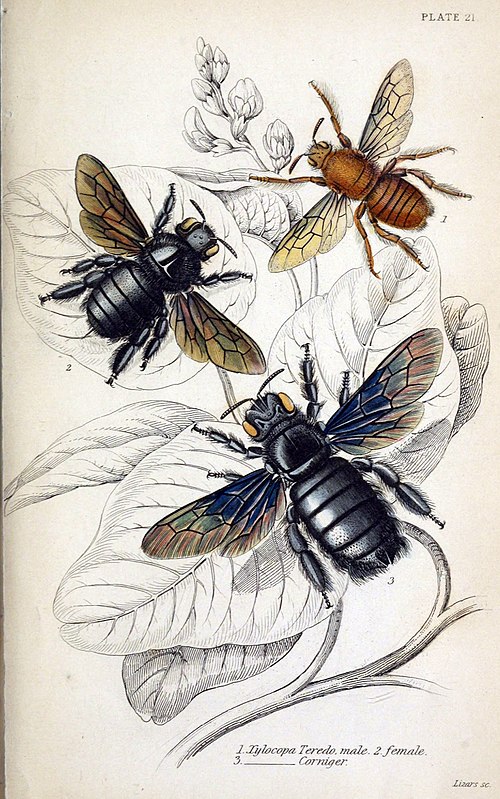

Lizars sc

HUBER.

Engraved for the Naturalist's Library. THE NATURALIST'S LIBRARY ENTOMOLOGY VOL. VI.

THE

NATURALIST'S LIBRARY.

CONDUCTED BY

SIR WILLIAM JARDINE, BART., F.R.S.E., F.L.S., &c. &c.

ENTOMOLOGY. VOL. VI. BEES.

COMPREHENDING THE USES AND ECONOMICAL MANAGEMENT OF THE HONEY-BEE OF BRITAIN AND OTHER COUNTRIES, TOGETHER WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF THE KNOWN WILD SPECIES.

EDINBURGH: W. H. LIZARS, 3, ST. JAMES' SQUARE; S. HIGHLEY, 32, FLEET STREET, LONDON; AND W. CURRY, JUN. & CO. LONDON. 1840. THE

W. H. LIZARS, 3, ST. JAMES' SQUARE; 1840. ADVERTISEMENT FROM THE PUBLISHER.

From the commencement of this Work it has been our uniform anxiety to adorn it with as much of pictorial beauty and interest as possible, and the present, although, at first appearance, embracing a subject not very favourable for such displays, will, we trust, be esteemed as not the least attractive in this respect, — while the absorbing interest of its literary details are probably second to none of the series. For the latter we are indebted to a reverend friend well known as one of the keenest observers, and most successful cultivators of the community of the tiny beings which form the subject before us. To our friend Mr. Duncan, the contributor of our Entomological volumes, the best acknowledgments are due for the extension of the subject in his interesting details of the Foreign and Wild species; and for the admirable manner in which he has conducted the volume through the press. He has availed himself of the invaluable assistance of Mr. Westwood for drawings and descriptions of various figures, which now, in some cases, appear before the public for the first time. Upon the whole, we hope it will be found that the present is an interesting volume in all its details; and, though last, not least in its attractions, in our having been enabled to enrich it with the only portrait of Huber known to have been published; and for which we are indebted to the Sister of the amiable person represented. Our next will be the second volume on the Dog, by Colonel H. Smith, and will contain an account of the domestic races and varieties, together with the different species of the Fox and Hyæna. 3, St. James' Square,

CONTENTS.

PAGE

In all thirty-two plates in this volume. MEMOIR OF HUBER. The Naturalist whose researches have been specially directed to the instinct and operations of the domestic Honey-Bee, will be strongly disposed to regard the subject of this memoir as at the very head of Apiarian science and his writings as forming the safest and most useful text-book. Multitudes have written on this interesting department of Natural History, and have added more or less to our knowledge of what has been a subject of investigation for ages. But none, either in ancient or modern times, have displayed so much sagacity of research as Francis Huber, nor so much patient perseverance and accuracy of experiment, even admitting some errors of minor importance detected by succeeding observers. His success in discovery, notwithstanding the singular difficulty he had to struggle with, was proportioned to his intelligence and acuteness; and this difficulty arose, not from what some of his advocates have, in their zeal in his defence against the sneers of the sceptical, termed "imperfect vision," but from total blindness. For, from the period when he first applied himself in good earnest to investigate the nature of his winged favourites, external nature presented to his eyes one universal blank; "So thick a drop serene had quenched their orbs." It is not, therefore, without reason that his friend and eulogist De Candolle[1] asserts that "nothing of any importance has been added to the history of bees since his time; and naturalists of unimpaired vision have nothing of consequence to subjoin to the observations of a brother who was deprived of sight." Francis Huber was born at Geneva on the 2d July, 1750. His father possessed a decided taste for subjects of natural science; the son inherited the taste of his father; and, even in his boyish days, pursued his favourite studies with such intense ardour as materially to injure his health, and bring on that weakness in his visual organs which eventually ended in total blindness. His attention had been led to what became his favourite,—indeed his sole and engrossing study, the habits and economy of the Honey-Bee, by his admiration of the writings of Reaumur, and above all, by his acquaintance with Bonnet,—the illustrious author of "Contemplation de la Nature," who quickly discerned the intelligence and penetration of his young friend, and who kindly and strongly encouraged him in his peculiar researches. It is singular enough that these two distinguished naturalists and friends should both have laboured under a similar personal defect occasioned, too, by the same causes; for the same intenseness and minuteness of observation which deprived Huber of sight altogether, had brought on in Bonnet a weakness of vision which for a time threatened total blindness, and from which he never fully recovered. It will readily occur to every one that the loss of sight in Huber must not only have presented a very serious obstacle to the successful study of his favourite science, but must have had the effect also of throwing considerable doubt on the accuracy of his experiments and the reality of his discoveries. His most devoted admirers and most unhesitating followers in every thing connected with the economy of Bees, are bound in candour to acknowledge, that his observations, reported, as they were, at second hand, and depending for their accuracy on the intelligence and fidelity of a half-educated assistant, were, of themselves, not entitled to be received without caution and distrust. Francis Burnens, his assistant, had no doubt entered with enthusiasm into the pursuit, and appears to have conducted the experiments not only with the most patient assiduity, but with great address and no small share of steadiness and courage, qualities indispensable in those who take liberties with the irritabile genus apum. Still Burnens was but an uncultivated peasant when he became Huber's hired servant, and possessed none of those acquired accomplishments which serve to sharpen the intellectual faculties, and fit the mind for observing and discriminating with correctness. It cannot reasonably excite our wonder, therefore, that on the first appearance of Huber's observations, the literary, or rather the scientific world, was somewhat startled, not only at the novelty of his discoveries, but also at the instrumentality by which they had been effected. Huber, however, had taken great pains in cultivating the naturally acute mind of the young man, in directing his researches, and accustoming him to rigorous accuracy in his observations. And the fact that a glimmering of many of the discoveries reported by the assistant to his master had presented themselves to the minds of Linnæus, Reaumur, and other preceding observers, should so far satisfy us that they were not brought forward merely to support a preconceived theory, (of which, it is probable, Burnens had no idea,) nor owed their origin to a vivid and exuberant imagination. At a future period Huber was deprived of the aid of this valuable coadjutor; but the loss was more than compensated, and accuracy in experiment and observation, if possible, still more unquestionably secured, by the assistance and co-operation of his son, P. Huber, who has given so much delight to the lovers of natural history by his "Researches concerning the habits of Ants." But, whatever hesitation may arise in our minds from the fact of Huber's discoveries not being the result of his personal observation, no doubt can reasonably remain as to such of them as have been repeatedly confirmed and verified by subsequent observers. And this has actually taken place, and holds strictly true in regard to the most important of them. His discoveries respecting the impregnation of the Queen-Bee,—the consequences of retarded impregnation,—the power possessed by the working-bees of converting a worker-larva into a Queen,—a fact, though not originally discovered by Huber, yet, until his decisive experiments and illustrations, never entirely known or credited,—the origin of Wax, and the manner of its elaboration,—the nature of Propolis,—the mode of constructing the combs and cells,—and of ventilating or renovating the vitiated atmosphere of the hives,—these, and a variety of other particulars of inferior moment, have almost all been repeatedly verified by succeeding observers, and many of them by the writer of this brief Memoir. It is readily admitted, that some of his experiments, when repeated, have not been attended by the results which he led us to expect; and some incidents in the proceedings of the Bees stated as having been observed by him or his assistant, have not yet been witnessed by succeeding observers. But in some of these, the error may have been in the repetition; in others, the result, even under circumstances apparently the same, may not always be uniform, for the instinct of Bees is liable to modification; and in some, he doubtless may be, and probably is, mistaken. In passing judgment, however, on his reported discoveries, we ought to keep in view, that the author of them has thrown more light on this portion of natural history, and pursued it with a more assiduous and minute accuracy, than all the other naturalists taken together, who have turned their attention to the same pursuits; and that therefore nothing short of the direct evidence of our senses, the most rigid scrutiny, and the most minute correctness of detail in experiment, can justify our denouncing his accuracy, or drawing different conclusions. His experiments were admirably fitted to elicit the truth, and his inferences so strictly logical, as to afford all reasonable security against any very important error. Huber's "Nouvelles observations sur les Abeilles", addressed in the form of letters to his friend Bonnet, appeared in 1792 in one volume. In 1814, a second edition was published at Paris in two volumes, comprehending the result of additional researches on the same subject, edited in part by his son. An English version appeared in 1806, and was very favourably noticed by the Edinburgh Review. A third edition of this translation was published in Edinburgh in 1821, embracing not only the original work of 1792, but also the several additions contained in that of 1814, and which had originally made their appearance in the Bibliothèque Britannique. These additional observations were, On the Origin of Wax, On the use of Farina or Pollen, On the Architecture of Bees, and On the precautions adopted by these insects against the ravages of the Sphinx Atropos. To enlarge on the personal character and domestic circumstances of Huber, falls not strictly within our province, which embraces only, or chiefly, his character and writings as a naturalist. There are however some features in his disposition, and some circumstances in his personal history, dwelt upon at considerable length by De Candolle,[2] which appear so well worthy the attention of our readers, that we cannot forego the opportunity of detailing them, though necessarily in an abridged form. His manners were remarkably mild and amiable,—as is frequently found to be the case with those who are afflicted with blindness,—and his conversation animated and interesting. "When any one," says his friend, "spoke to him on subjects which interested his heart, his noble figure became strikingly animated, and the vivacity of his countenance seemed by a mysterious magic to animate even his eyes, which had so long been condemned to blindness." It appears that some of his friends would gladly have persuaded him to try the effect of an operation on one of his eyes, which seemed to be affected only by simple cataract; but he declined the proposal, and bore not only without complaint, but with habitual cheerfulness, his sad deprivation. His marriage with Maria Aimée Lullin, the daughter of a Swiss magistrate, was in a high degree romantic. The attachment had begun in their early youth, but was opposed by the lady's father on the ground of Huber's increasing infirmity; for even then, the gradual decay of his organs of vision was become but too manifest. The affection and devotedness of the young lady, however, appeared to strengthen in proportion to the helplessness of their object. She declared to her parents, that although she would have readily submitted to their will, if the man of her choice could have done without her; yet as he now required the constant attendance of a person who loved him, nothing should prevent her from becoming his wife. Accordingly, as soon as she had attained the age which she imagined gave her a right to decide for herself, she, after refusing many brilliant offers, united her fate with that of Huber. The union was a happy one. Their mutual good conduct soon brought about the pardon of their disobedience. In the affection and society of his amiable and generous minded wife, the blind man felt no want; she was "eyes to the blind,"—"his reader,—his secretary and observer,"—a sharer in his enthusiasm on the subject of natural science, and an able assistant in his experiments. She was spared to him forty years. "As long as she lived," said he in his old age, "I was not sensible of the misfortune of being blind." The last years of his life were soothed by the affectionate attentions of his married daughter, Madame de Molin,[3] whose residence was at Lausanne, and to which place he had removed. It was about this period that he learned the existence in Mexico of Bees without stings; and he was, by the kind exertions of a friend, soon after gratified with the present of a hive of that species. To him, whose life had been almost exclusively devoted to the study and admiration of these insects, we may conceive how great a source of enjoyment this gift must have proved. His feeling towards his bees was not a feeling of fondness in an ordinary degree; it was a passion as it almost invariably becomes with every one who makes them his study. "Beaucoup de gens aiment les abeilles," says the enthusiastic Gelieu, "je n'ai vu personne qui les aima médiocrement; on se passionne pour elles." The days of Huber were now drawing to a close. In the full possession of his mental faculties, he was able to converse with his friends with his accustomed ease and tranquillity, and even to correspond by letter with those at a distance, within two days of his death. He died in the arms of his daughter on the 22d of December 1831, in the 81st year of his age. THE HONEY-BEE. APIS MELLIFICA. PLATE I.

The domestic Honey-Bee has excited a lively and almost universal interest from the earliest ages. The philosopher and the poet have each delighted in the study of an insect whose nature and habits afford such ample scope for inquiry and contemplation; and even the less intellectual peasant, while not insensible of the profit arising from its judicious culture, has regarded, with pleasure and admiration, its ingenious operations and unceasing activity. "Wise in their government," observes the venerable Kirby, "diligent and active in their employments, devoted to their young and to their queen, the Bees read a lecture to mankind that exemplifies their oriental name Deburah, she that speaketh." So high did the ancients carry their admiration of this tiny portion of animated nature, that one philosopher, it is said, made it the sole object of his study for nearly three-score years ; another retired to the woods, and devoted to its contemplation the whole of his life; while the great Latin poet, the enthusiastic Virgil, stating, and probably adopting, a prevalent opinion, speaks of the Bee as "having received a direct emanation from the divine intelligence." After all this study, however, these enthusiastic admirers have thrown but little light on the real nature of this extraordinary insect; and while they have handed down to us many judicious precepts for its practical treatment, their disquisitions on its natural history can now only excite a smile. The chief cause of this failure may be fairly ascribed, perhaps, to the want of those facilities for discovery which modern science has afforded, and by which the most hidden mysteries of Bee economy are rendered clear and palpable. A host of writers on the nature of the Bee appeared during the last century, who, availing themselves of the improvements in general science, made many interesting additions to our stock of knowledge on the subject. Swammerdam, Maraldi, Reaumur, Bonnet, Schirach, and more recently Huber on the Continent, and Thorley, Wildman, Keys, Hunter, and Bonner, among ourselves, multiplied, a hundred-fold, the discoveries of Aristotle, Columella, and Varo; and the vague conjectures and fabulous details of the latter philosophers, have been succeeded by rational research and discriminating experiment. But even in the investigations of the first named writers, not excepting the most accurate and successful experimenter of them all, the indefatigable Huber, there are some obvious errors which longer experience and observation have been enabled to detect, and some questionable statements which can he attributed only to a want of cool and dispassionate inquiry. In fact, much has been written and published on the subject calculated to startle a sober reader; and some of those discoveries which have been blazoned in publications, both at home and abroad — though most frequently, perhaps, on the Continent — will be found, on strict examination, to have no existence but in the warm fancy or blind enthusiasm of the observers. The incontrovertible facts in the natural history of the Bee, are, in themselves, too remarkable to justify any attempt to draw upon the imagination for additional wonder; and the Naturalist who is desirous of making himself thoroughly acquainted with the instincts and habits of this interesting little creature, should be cautious in considering, as an established fact, any discovery, or supposed discovery, which has not been, again and again, verified by rigid experiment. In the following details, embracing the Natural History and Practical Management of the Honey-Bee, we have endeavoured to avoid this error, stating nothing as fact, but what we know to be so from undoubted testimony, or from our own knowledge and experience. At the same time, we have not omitted to notice such alleged discoveries or results of experiments, as appear to us to be unsupported by sufficient evidence, or at variance with experiments of our own, made for the express purpose of verification, leaving it to the reader to receive or reject them as his judgment may dictate. We have availed ourselves of the information dispersed throughout a variety of publications, both ancient and modern,[4] with such additions of our own, as have been acquired by the observation of Bees for a period of thirty years. Our prescribed limits have restricted us, in a great degree, to mere matters of fact, and prevented us often from illustrating our subject, as we might have done with advantage, by reference to the habits and instincts of other of the insect tribes. The same cause has operated as a bar to our indulging so frequently as our inclination would have led us, in those reflections which the wonders in animal economy are so well fitted to excite, and which lead so irresistibly to the conclusion that there is a Wise and Designing Cause. We trust, however, that the facts detailed, will, of themselves, lead the mind of the intelligent reader to such reflections, and thus become the source of a purer gratification than would have been derived from the suggestions of others. **Some of our readers may be inclined to question the propriety of having placed the Queen-bee upon flowers, on which she is never seen, but it has, throughout our plates, been our endeavour to make them pictorial as well as scientifically correct, the more necessary in a volume such as the present, where our materials are rather scanty, a loss, however, fully compensated by the extraordinary interest in the subject itself. ON THE ANATOMY OF THE HONEY-BEE.

The body of the insect is about half an inch long, of a blackish-brown colour which deepens with age, and is wholly covered with close-set hairs, which assist greatly in collecting the farina of flowers. (Wood-cut, Fig. 2.)

Tearing open the anthers of the plant on which it has alighted, and rolling its little body in the bottom of the corolla, the insect rapidly brushes off the farina, moistens it with its mouth, and passes it from one pair of legs to another, till it is safely lodged in the form of a kidney-shaped pellet in a spoon-like receptacle in its thigh to be afterwards noticed. These hairs deserve to be particularly remarked on account of their peculiar formation, being feather-shaped, or rather consisting each of a stem with branches disposed around it, and, therefore, besides their more effectually retaining the animal heat, peculiarly adapted for their office of sweeping off the farina. The Head, which is of a triangular shape and much flattened, is furnished with a pair of large eyes, (Wood-cut, p. 31, Fig. 1, aa,) of what is called by naturalists the composite construction, and consisting of a vast assemblage of small hexagonal surfaces, disposed with exquisite regularity, each constituting in itself a perfect eye; they are thickly studded with hairs, which preserve them from dust, &c. In addition to these means of vision, the bee is provided with three small stemmata, or coronetted eyes, situated in the very crown of the head, and arranged in the form of a triangle. These must add considerably to the capacity of vision in an insect whose most important operations are carried on in deep obscurity. As to the special or peculiar use these ocelli may serve, Reaumur and Blumenbach were of opinion, that, while the large compound organs are used for viewing distant objects, the simple ones are employed on objects close at hand. It is not improbable, however, that these last, from their peculiar position, are appropriated to upward vision. The Antennæ (Fig. 1. b.) present us with another remarkable appendage of the head. These are two tubes about the thickness of a hair, springing from between the eyes, and a little below the ocelli; they are jointed throughout their whole length, each consisting of twelve articulations, and therefore capable of every variety of flexure. Their extremities are tipped with small round knobs, exquisitely sensible; and which, from their resemblance to the stemmata or ocelli, have been supposed by some to serve as organs of vision; by others, as connected with the sense of hearing; and by others, as organs of feeling or touch. This last seems the most probable conjecture, as on approaching any solid object or obstacle, the Bee cautiously brings its antennæ in contact with it, as if exploring its nature. The insects use these organs, also, as a means of recognizing one another; and an interesting instance is stated by Huber, in which they were employed to ascertain the presence of their queen, (vide page 48.) The Mouth of the Bee comprehends the tongue, the mandibles or upper jaws, the maxillæ or lower jaws, the labrum or upper lip, the labium or lower lip, with the proboscis connected with it, and four palpi or feelers. The tongue of the Bee, like that of other animals, is situated within the mouth, and is so small and insignificant in its form, as not to be easily discernible. In most anatomical descriptions of the Bee, the real tongue, now described, has been erroneously confounded with the ligula or central piece of the proboscis, afterwards to be described. The upper jaw (Wood-Cut, page 31, fig. 1. c, c.) of the Bee, as of all other insects, is divided vertically into two, thus forming, in fact, a pair of jaws under the name of mandibles. They move horizontally, are furnished with teeth, and serve to the little labourers as tools, with which they perform a variety of operations, as manipulating the wax, constructing the combs, and polishing them, seizing their enemies, destroying the drones, &c. The lower jaws or maxillæ, divided vertically as the others, form, together with the labium or under lip, the complicated apparatus of the Proboscis. Its parts are represented in the following figure.  This organ, beautiful in its construction, and admirably adapted to its end, serving to the insect the purpose of extracting the juices secreted in the nectaries of flowers, consists, principally, of a long slender piece, named, by entomologists, the Ligula, and erroneously, though, considering its position and use, not unnaturally, regarded as the tongue, (Wood-Cut, page 34, fig. a.) It is, strictly speaking, formed by a prolongation of the lower lip. It is not tubular, as has been supposed, but solid throughout, consisting of a close succession of cartilaginous rings, above forty in number, each of which is fringed with very minute hairs, and having also a small tuft of hair at its extremity. It is of a flattish form, and about the thickness of a human hair; and from its cartilaginous structure, capable of being easily moved in all directions, rolling from side to side, and lapping or licking up whatever, by the aid of the hairy fringes, adheres to it. It is probably, by muscular motion, that the fluid which it laps, is propelled into the pharynx or canal, situated at its root, and through which it is conveyed to the honey-bag. From the base of this lapping instrument, arise the labial Palpi or Feelers, composed of four articulations, (b, b.) of unequal length, the basal one being by much the longest, and whose peculiar office is to ascertain the nature of the food; and both these and the ligula are protected from injury by the maxillæ or lower jaws, (c, c.) which envelop them, when in a quiescent state, as between two demi-sheaths, and thus present the appearance of a single tube. About the middle of the maxillæ, are situated the maxillary palpi, of very diminutive size, but having the same office to perform as those situated at the base of the ligula. The whole of the apparatus is capable of being doubled up by means of an articulation or joint in the middle. The half next the lip bends itself inwards, and lays itself along the other half which stretches towards the root, and both are folded together, within a very small compass, under the head and neck. The whole machinery rests on a pedicle, not seen in the figure, which admits of its being drawn back or propelled forwards to a considerable extent. The celebrated naturalist, Ray, whose knowledge of the minutiae of insect anatomy was but slender, "was," Kirby remarks, "at a loss to conceive what could be the use of the complex machinery of the proboscis. We who know the admirable art and contrivance manifested in the construction of this organ, need not wonder, but we shall be inexcusable if we do not adore."[5] The Trunk of the Bee, or Thorax, (Wood-Cut, p. 31, fig. 2, a.) approaches in figure to a sphere, and is united to the head by a pedicle or thread-like ligament. It contains the muscles of the wings and legs. The former consist of two pair of unequal size, and are attached to each other by slender hooks, easily discernible through a microscope, and thereby their motion, and the flight of the insect, are rendered more steady. Behind the wings, on each side of the Trunk, are situated several small orifices, called stigmata or spiracles, through which respiration is effected. These orifices are connected with a system of air-vessels, pervading every part of the body, and serving the purpose of lungs. The rushing of the air through them against the wings, while in motion, is supposed to be the cause of the humming sound made by the Bees. To the lower part of the trunk are attached three pair of Legs. The anterior pair, which are most efficient instruments, serving to the insect the same purpose as the arms and hands to man, are the shortest, and the posterior pair the longest. In each of these limbs there are several articulations or joints, of which three are larger than the others, serving to connect the thigh, the leg or pallet, and the foot or tarsus; the others are situated chiefly in the tarsus. (Plate II. Fig. 2., a. the haunch, b. the thigh, c. the tibia or pallet, containing on the opposite side, as represented at Fig. 4 a., the basket or cavity; d, e. the foot.) In each of the hinder limbs, one of which is represented in Plate II. Fig. 2, there is an admirable provision made for enabling the Bee to carry to its hive an important part of its stores, and which neither the queen nor the male possess, being exempted from that labour, viz. a small triangular cavity of a spoon-like shape, the exterior of which is smooth and glossy, while its inner surface is lined with strong close-set hairs. This cavity forms a kind of basket, destined to receive the pollen of flowers, one of the ingredients composing the food of the young. It receives also the propolis, a viscous substance, by which the combs are attached to the roof and walls of the hive, and by which any openings are stopped that might admit vermin or the cold. The hairs with which the basket is lined, are designed to retain firmly the materials with which the thigh is loaded. The three pair of legs are all furnished, particularly at the joints, with thick-set hairs, forming brushes, some of them round, some flattened, and which serve the purpose of sweeping off the farina. There is yet another remarkable peculiarity in this third pair of limbs. The junction of the pallet and tarsus is effected in such a manner as to form, by the curved shape of the corresponding parts, "a pair of real pincers, A row of shelly teeth, (Pl. II. Fig. 3 a,) like those of a comb, proceed from the lower edge of the pallet, corresponding to bundles of very strong hairs, with which the neighbouring portion of the brush is provided. When the two edges of the pincers meet—that is, the under edge of the pallet, and the upper edge of the brush, the hairs of each are incorporated together."[6] The extremities of the six feet or tarsi, terminate each in two hooks, with their points opposed to each other, by means of which the Bees fix themselves to the roof of the hive, and to one another, when suspended, as they often are, in the form of curtains, inverted cones, festoons, ladders, &c. From the middle of these hooks proceeds a little thin appendix, which, when not in use, lies folded double through its whole breadth; when in action it enables the insect to sustain its body in opposition to the force of gravity, and thereby adhere to, and walk freely and securely upon glass and other slippery substances, with its feet upwards. The Abdomen, (Plate III. figs. 3, 4, 5, & 6,) attached to the posterior part of the thorax by a slender ligament like that which unites the thorax and the head, consists of six scaly rings of unequal breadth. It contains two stomachs, the small intestines, the venom-bag, and the sting. An opening, placed at the root of the proboscis, is the mouth of the oesophagus or gullet, which traverses the trunk, and leads to the anterior stomach. This last named vessel is but a dilatation of the gullet, and in fact forms the honey-bag. When full, it exhibits the form of a small transparent globe, somewhat less in size than a pea. It is susceptible of contraction, and so organised as to enable the Bee to disgorge its contents. The second stomach, which is separated from the first, of which it appears to be merely a continuation, only by a very short tube, is cylindrical, and very muscular; it is the receptacle for the food, which is there digested, and conveyed by the small intestines to all parts of the body for its nutriment. It receives also the honey from which wax is elaborated. Scales of this last mentioned substance are found ranged in pairs, and contained in minute receptacles under the lower segments of the abdomen. No direct channel of communication between the stomach and these receptacles or wax-pockets has yet been discovered; but Huber conjectures that the secreting vessels are contained in the membrane which lines these receptacles, and which is covered with a reticulation of hexagonal meshes analogous to the inner coat of the second stomach of ruminating quadrupeds, Plate III. Fig. 1, copied from Huber, gives a representation of one of the segments or rings, in which a b is a small horny prominence, forming the division between two areas which are bounded by a solid edge c n d g m e. "The scales of wax, (Fig. 2,) are deposited in these two areas, and assume the same shape, viz. an irregular pentagon. Only eight scales are furnished by each individual Bee, for the first and last ring, constituted differently from the others, afford none. The scales do not rest immediately on the body of the insect; a slight liquid medium is interposed, which serves to lubricate the junctures of the rings, and facilitate the extraction of the scales, which might otherwise adhere too firmly to the sides of the receptacles."[7]  The Sting with its appendages, (annexed Wood-Cut) lies close to the last stomach, and, like the proboscis, may seem to the naked eye a simple instrument, while it is, in fact, no less complex in its structure than the former apparatus. Instead of being a simple sharp-pointed weapon, like a fine needle, it is composed of two branches or darts, a a, applied to each other longitudinally, and lodged in one sheath, b b. One of these darts is somewhat longer than the other; they penetrate alternately, taking hold of the flesh, till the whole sting is completely buried. The sheath is formed by two horny scales, (themselves inclosed within two fleshy sheaths, c c, along the groove of which, when the sting is extruded, flows the poison from a bag or reservoir d, in the body of the insect near the root of the sting. The darts composing this weapon, are each furnished with five teeth or barbs, set obliquely on their outer side, which give the instrument the appearance of an arrow, and by which it is retained in the wound it has made, till the poison has been injected; and though it is said the insect has the power of raising or depressing them at pleasure, it often happens that when suddenly driven away, it is unable to extricate itself without leaving behind it the whole apparatus, and even part of its intestines; death is the inevitable consequence. Though detached from the animal, this formidable weapon still retains, by means of the strong muscles by which it is impelled, the power of forcing itself still deeper. On the subject of the sting, Paley[8] ingeniously remarks: "The action of the sting affords an example of the union of chemistry and mechanism; of chemistry, in respect to the venom which in so small a quantity can produce such powerful effects: of mechanism, as the sting is not a simple, but a compound instrument. The machinery would have been comparatively useless—telum imbelle—had it not been for the chemical process, by which, in the insect's body, honey is converted into poison; and on the other hand, the poison would have been ineffectual without an instrument to wound, and a syringe to inject the fluid." Having noticed these particulars in the anatomical structure of the working-bee, as the general representative of the species, we shall next point out in what it differs from the conformation of the queen, and the male or drone. The queen is frequently styled by the Continental Naturalists the Mother-Bee, and with great propriety; as it seems now ascertained that her distinguishing qualities have a closer reference to the properties of a parent, than to the province of a sovereign. Her body differs from that of the worker, (Pl. 1, fig. 2,) in being considerably larger, and of a deeper black in the upper parts, while the under surface and the limbs are of a rich tawny colour. Her proboscis is more slender; her legs are longer than those of the worker, but without the hairy brushes at the joints; and as she is exempted from the drudgery of collecting farina or propolis, the posterior pair are without the spoon-like cavity found in those of her labouring offspring. When about to become a mother, her body is considerably swollen and elongated, and her wings in consequence appear disproportionally short. The abdomen of the queen contains the ovarium, (Plate IV.,) consisting of two branches, each of which contains a large assemblage of vessels filled with eggs, and terminating in what is called the oviduct. This duct, when approaching the anus, dilates itself into a larger receptacle into which the eggs are discharged, and which is considered by Naturalists as the sperm-reservoir, or depository of fecundating matter; from thence they are extruded by the insect, and deposited in the cell prepared for their reception. The sting possessed by the Queen is bent, while that of the worker is straight; it is seldom, however, brought into action,—perhaps only in a conflict with a rival queen. The male, (Pl. 1, fig. 1,) is considerably more bulky than the working Bee. The eyes are more prominent; the antennæ have thirteen articulations instead of twelve; the proboscis is shorter, the hind-legs have not the basket for containing farina, and he is unprovided with a sting. The cavity of the abdomen is wholly occupied with the digestive and reproductive organs. The very loud humming noise he makes in flying, has fixed upon him the appellation of Drone. THE SENSES OF BEES.