The New International Encyclopædia/Lincoln, Abraham

LINCOLN, Abraham (1809-65). The sixteenth President of the United States, born in Hardin County, Ky., February 12, 1809. His ancestry has been with some difficulty traced back to Samuel Lincoln, of Norwich, England, who emigrated to America and settled in Hingham, Mass., in 1638. Some of his descendants, who were Quakers, settled in Amity Township, N. J., and finally in Rockingham County, Va. The Virginia Lincolns are described as “reputable and well-to-do.” One of them, the President's grandfather, removed to Jefferson County, Ky. Thomas Lincoln, Abraham's father, a carpenter by trade, was ignorant and thriftless. He married Nancy Hanks, who seems to have belonged to an obscure family, but herself to have been a woman of noble character. After several removals in Kentucky, Thomas Lincoln went in 1816 to Indiana. At the new home his wife died after two years, when Abraham was not quite eight years old, and a year later he married Mrs. Sally (Bush) Johnson, whom he had formerly courted. All Abraham's schooling combined would probably not have made up more than one year. As he grew up, however, he had access to a few books which he read and reread — the Bible, Shakespeare, Æsop's Fables, Robinson Crusoe, Pilgrim's Progress, a history of the United States, and Weems's Washington. He seems to have been ambitious from the outset, trying hard to learn, but much influenced by the coarseness of his surroundings, from the externals of which he never got quite free. He grew to be six feet four inches in height; marvelous tales are told of his strength, and much more credible ones of his laziness, skill at jesting and story-telling, and popularity.

When Abraham was twenty-one his father's migratory nature impelled him to try his fortunes in Illinois, and he settled on the north fork of the Sangamon, which empties into the Illinois. Here the younger Lincoln helped to split rails and to clear and plant some fifteen acres. In 1831, with two relatives, he took a flatboat to New Orleans, whither he had made a previous trip. Ten years later he went to New Orleans again. These trips enabled him to see the true nature of slavery. In 1832 Lincoln was chosen captain of a company of volunteers for service in the Black Hawk War. They saw no fighting and were mustered out within five weeks, when Lincoln reënlisted as a private, serving until June 16th. He then returned to Sangamon, making his abode at the little mushroom town of New Salem, and, having announced his candidacy for the State Legislature, he began electioneering vigorously. With great humor and with an energy not always confining itself to strict argument, he advocated pure Whig doctrine — a national bank, internal improvements, and a protective tariff. The follower of Clay was beaten by the Jacksonian Democrats, but be had gained experience and had spread his popularity. His next venture was as a partner in a dry-goods and grocery store at New Salem, but the concern failed, the partner fled, and Lincoln was left to settle the losses. He paid all he owed in 1849. Having no gift for trade, he now began to read law, studied hard, and made swift headway. In May, 1833, he was appointed postmaster at New Salem, and is said to “have carried the post-office in his hat,” for the mail came but once a week. This position he held three years. In 1834 Lincoln's personal properly was about to be sold by the sheriff to satisfy a judgment, when a new friend, Bolin Greene, bid in the property and gave it over to him. In 1834 he was again a candidate for the Legislature, and was elected, running far ahead of his ticket. He was rather an observer than an active legislator in this session.

Lincoln's first love was unhappy. While boarding with James Rutledge, in New Salem, he became enamored of Ann, his landlord's daughter, a well-reared girl of seventeen. She had at the time another lover, who promised marriage, but he broke his word. Lincoln and Ann Rutledge were betrothed in 1835, but the girl fell ill, and in August she died of brain fever.

In 1836 Lincoln was again a candidate for the Legislature on the following characteristic platform: “I go for all sharing the privilege of the Government who assist in bearing its burdens. Consequently, I go for admitting all whites to the rights of suffrage who pay taxes or bear arms, by no means excluding females.” Lincoln stumped the district, and by his vigorous speeches won a Whig victory. In the Presidential contest of 1836 Lincoln was for Hugh L. White of Tennessee. In the struggle of Jackson against the United States Bank and the shifting policy of Van Buren he had no interest, but he heeded his duties as a legislator, and began that anti-slavery record upon which so much of his fame will ever rest. The abolitionists were in the highest activity. Garrison's Liberator was intensely annoying to the upholders of slavery. President Jackson had at the close of 1835 invited the attention of Congress to the circulation through the mails of what were then called ‘inflammatory’ documents. Henry Clay, Edward Everett, many of the Governors of the Northern States, and a large majority of the House of Representatives strenuously opposed the agitation of the slavery question; all petitions to Congress on the subject were laid on the table without reading or debate, and all possible means were taken to prevent the discussion of the hateful subject. On the night of November 7, 1837, the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy was mobbed and shot dead at Alton, Ill., for persisting in publishing an abolition newspaper.

At this juncture, when the Legislature was

about to pass resolutions deprecating the

anti-slavery agitation, Lincoln presented his protest,

to which he could get but one signer besides

himself. Herein he declares slavery to be founded

on injustice and bad policy; but he avers that

abolition agitation tends to increase slavery's

evils; that Congress may not interfere with

slavery in the States, though it might in the

District of Columbia on the request of the people.

This protest was meant to avoid extreme views;

therefore no mention was made of slavery in

the Territories, that point being covered by the

Missouri Compromise, which was then in full

force. Lincoln was never extreme, and probably

till the war began he saw no hour when he would

have altered a word in this protest.

When the State capital was removed to Springfield in 1839, Lincoln settled there. Two years before he had been licensed as an attorney, and being at the capital, he could attend both to his duties as a member of the Legislature and his law practice. His business grew so rapidly that he took into partnership John T. Stuart, a prominent Whig, who had been a good friend also in former years. Lincoln preferred to be the junior in the firm. Springfield was a village of about 1500 inhabitants, and Lincoln was not only poor, but he was in debt.

In 1840 Lincoln was an elector on the Harrison ticket, and made speeches in all parts of the State. But one-sided speeches were not suited to his temper; he preferred joint debates, wherein he might employ his masterly skill at retort. A year earlier Lincoln had made the acquaintance of Mary, the daughter of the Hon. Robert S. Todd, of Lexington, Ky., and a sister of the wife of Ninian W. Edwards, of Springfield, a distinguished lawyer. Through her comeliness and her wit the young lady had gained many admirers. Some political papers were contributed by her to a local newspaper; and Lincoln, to shield her, assumed the responsibility, barely avoiding a duel. About six weeks afterwards, November 4, 1842, he married Miss Todd.

In 1844 Lincoln was once more an elector on the Clay (Whig) ticket, and in 1846 he was elected to Congress by 1511 majority in a district which two years before had given him only 914. When he took his seat as Representative in the Thirtieth Congress, his great rival, Stephen A. Douglas, was in the Senate. Lincoln was put on the Committee of Post-Offices and Post-Roads. Though opposed to the Mexican War, he voted for supplies to carry it on. In 1848 he favored the nomination, by the Whigs, of Taylor for President, and made a strong speech in the House for that purpose, subsequently speaking in various parts of the country. In the second session of the Thirtieth Congress he made no special mark. His law partnership with Stuart ended April, 1841, when he united in practice with ex-Judge Stephen T. Logan, and soon afterwards formed a partnership with his best friend, William H. Herndon. As a lawyer he spoke tellingly and often to the mirth of the courtroom. Many curious anecdotes are told of the great man as a story-teller, of his power, his energy, his oddities, and his generosity. Though thousands of good stories unknown to Lincoln pass current as having been told by him, it is true that few great statesmen were more capable than he of perceiving the kernel of a tale. He had also a ready and humorous wit, and was quick to follow a good parry with a well-aimed thrust.

When his term in Congress was over Lincoln wished to be Commissioner of the General Land Office, but he did not get the appointment. He was offered the Governorship of Oregon Territory, but his wife declined to go there, and he would not accept. For two years after leaving Congress he was not prominent. In 1850 he refused a nomination for Congress. July 1, 1852, he was selected at a meeting of citizens to deliver a eulogy on Henry Clay. The bill offered by Douglas, January 4, 1854, to establish a Territorial Government in Nebraska, reopened the anti-slavery war, and Lincoln was forced to take decided ground against spreading slavery into the Territories. This he did at the State Fair at Springfield, Ill., in October, in a speech of great power. Lincoln had felt that his natural opponent was Douglas and he seized eagerly this opportunity of refuting his arguments; Douglas recognized his opponent's strength and secured from him a truce from debating for that fall. In November, despite his positive declination, Lincoln was again elected to the Legislature. At the same time he was very desirous to succeed Shields (a Democrat) in the United States Senate; but Lyman Trumbull carried off the prize. During the Kansas excitement Lincoln's sympathies were all in favor of the free-State side, but he discountenanced the use of force.

It was at the State Convention at Bloomington in 1856 that the Republican party in Illinois was formed, and there Lincoln made what many deem the greatest of all his speeches. This speech, preserved only in description, took advanced anti-slavery ground and was undoubtedly earnest and powerful. On June 17, 1856, at the Republican Nominating Convention at Philadelphia, Lincoln's name was put forth for Vice-President, and was received with considerable favor, for he got 110 votes. This year, for the third time, Lincoln was on the electoral ticket, now as a Republican, and he made some fifty speeches for Frémont. The quality of these speeches bettered his reputation and spread it even to the East. In April, 1858, the Democrats indorsed the stand Douglas had taken in the Kansas dispute, and nominated him for the Senate. Lincoln expected and received the Republican nomination in June, and in accepting he delivered the carefully thought out speech which contained the famous statement that a house divided against itself cannot stand. In July he challenged Douglas to the now famous seven debates, the direct result of which was to win the latter the Senatorship. Lincoln, however, was not arguing for the Senatorial prize alone, but with a greater purpose — he was fighting for Republican success in the Presidential contest of 1860, and the opportunity it would bring to ‘hit hard’ the great ‘moral, social, and political wrong’ of slavery.

In April, 1859, the people of his own town began to talk of Lincoln as a proper candidate for President, but he discouraged the idea. In September he made speeches in Ohio in the track of Douglas; in December he spoke at several places in Kansas. He was more and more talked of for a Presidential nomination, and finally authorized his friends to work for him. On February 27, 1860, on invitation, he appeared in New York and spoke in Cooper Institute. The address was warmly praised in most of the city journals, and was in fact highly successful. After this he spoke in many cities in New England. He was present, though not a delegate, at the Illinois State Convention, May 9, 1860, where he received the most flattering evidences of his great popularity, which was fully assured by the adoption without dissent of a resolution declaring him the choice of the Republicans of Illinois for President.

On May 16, 1860, the Republican National Convention met at Chicago. The city was full of political workers. Indeed, no previous convention had had half the number of ‘outside delegates.’ Two days were spent in organization and the adoption of a platform. Balloting came on the third day. Up to the previous evening Seward's nomination seemed certain; but the outside pressure for Lincoln was powerful, for his friends were chiefly men of Illinois, and the convention was held in their State. On the third ballot Lincoln won the nomination, and in the afternoon Hannibal Hamlin, of Maine, was nominated for Vice-President. The platform adopted, though denying the right of Congress to interfere with slavery in the States, demanded that slavery be forbidden in the Territories. It declared in favor of internal improvements and protection.

The Democratic National Convention at Charleston split on the slavery question. The South totally repudiated Douglas and his squatter sovereignty, whereas Douglas was equally determined to stick to it. Most of the Southern delegates withdrew and organized a separate convention. Those who remained voted fifty-seven times for a candidate, Douglas always having the highest number, but not the two-thirds required by Democratic precedent. They adjourned to meet at Baltimore, June 18th. The seceders adjourned to meet at Richmond, Va., early in June, but after convening they further adjourned to meet June 28th in Baltimore. The result finally was the nomination of three Presidential candidates: Douglas by one convention, Breckenridge of Kentucky by the seceders, or extreme Southerners, and Bell (formerly a Whig) of Tennessee, by the ‘Constitutional Union’ Party, comiposed for the most part of ‘Know-Nothings’ and old-time Whigs. The canvass was warm on all sides. Lincoln was elected on November 6th by 180 votes, Breckenridge receiving 72, Bell 39, and Douglas 12. The election was strictly sectional, for the Republicans got no electoral vote in a Southern State. Feeling the need of all possible support, Lincoln chose his Cabinet carefully, trying to get a varied representation; he wished even to have a Southerner, until his offer to Mr. Graham, of North Carolina, was flatly refused. Meanwhile the South was making ready to secede, and on December 20th the South Carolina Convention unanimously adopted the ordinance of secession. The year closed in gloom, and 1861 opened with no hope of peace. On February 4th a peace congress met in Philadelphia; on the same day delegates met at Montgomery, Ala., to form a Southern Confederacy; on the 18th the work was done, and Jefferson Davis was inaugurated President.

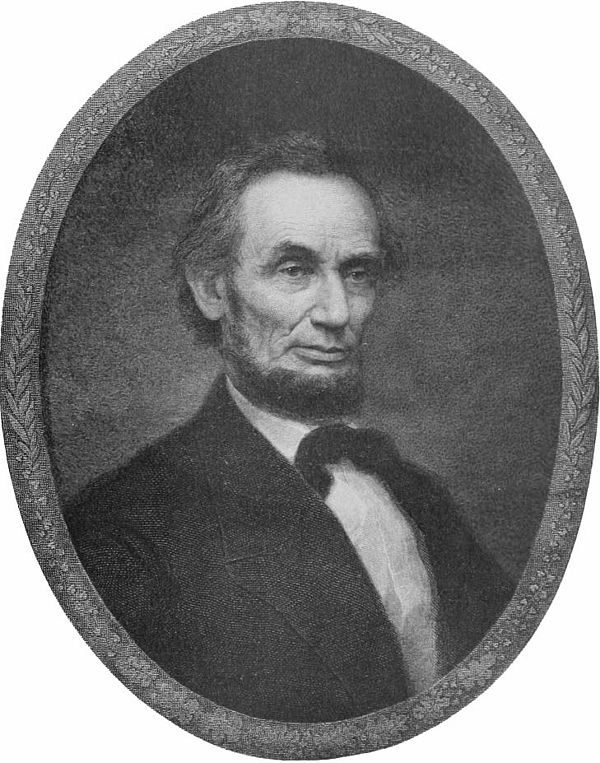

On February 11, 1861, Lincoln set out for Washington, taking a rather roundabout road. Everywhere the people were eager to see and hear him. On Monday, March 4th, he was inaugurated, and delivered an elaborate address, full of the best qualities of his nature. The appearance of the new President is thus described by Ward Lamon, in his Life of Abraham Lincoln: “He was six feet four inches high, the length of his legs being out of all proportion to that of his body. When he sat on a chair he seemed no taller than an average man, measuring from the chair to the crown of his head; but his knees rose high in front. He weighed about 180 pounds, but was thin through the breast, narrow across the shoulders, and had the general appearance of a consumptive subject. Standing up, he stooped slightly forward; sitting down, he usually crossed his long legs or threw them over the arms of the chair. His head was long and tall from the base of the brain and the eyebrow; his forehead high and narrow, inclining backward as it rose. His ears were large and stood out; eyebrows heavy, jutting forward over small sunken blue eyes; nose long, large, and blunt; chin projecting far and sharp, curved upward to meet a thick lower lip, which hung downward; cheeks flabby, the loose skin falling in folds; a mole on one cheek, and an uncommonly prominent Adam's apple in his throat. His hair was dark brown, stiff and unkempt; complexion dark, skin yellow, shriveled, and leathery. Every feature of the man — the hollow eyes, with the dark rings beneath, the long, sallow, cadaverous face, intersected by those peculiar deep lines, his whole air, his walk, his long and silent reveries, broken at intervals by sudden and startling exclamations, as if to confound an observer who might suspect the nature of his thoughts — showed that he was a man of sorrows, sorrows not of to-day or yesterday, but long-treasured and deep, bearing with him continual sense of weariness and pain.” Yet this strangely sorrowful man dearly loved jokes, puns, and comical stories, and was himself world-famous for his inimitable narrative powers. He drank very little, and was in precept and example for temperance; and at table he always ate sparingly. He was never a member of a church; indeed, he is believed to have had doubts of the divinity of Christ and of the inspiration of the Scripture, i.e. of revelation. In early life he read Volney and Paine, and wrote an essay in which he agreed with their conclusions. Of modern thinkers he was thought to agree most with Theodore Parker.

At his inauguration Lincoln denied the right of any State or number of States to go out of the Union. In the South the address was regarded as practically a declaration of war, and preparations were hurried; in the North it was strongly approved, and parties were quickly consolidated. Less than six weeks afterwards, General Beauregard, on behalf of the Confederate Government, bombarded Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, forcing the surrender of Major Anderson and his small force on April 14th. There began the Civil War, and from that day to the day of his death the political biography of Lincoln is nearly identical with the history of the United States. On April 15th he called for 75,000 volunteers, and hundreds of thousands in the first flush of patriotic feeling thronged to enlist. At the same time Lincoln called for a special session of Congress to meet on the Fourth of July. On April 19th he proclaimed a blockade of the Southern ports; on April 27th he authorized the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. The date for the meeting of Congress had been made distant, not only to allow the President to develop his policy and to avoid the turmoil that would ensue if the members met in the height of passion, but also to take advantage of the famous holiday — thus satisfying a curious superstitious streak in Lincoln's nature. The only direct request made was for 400,000 men and $400,000,000. The request was granted with additions. On July 15th a Democratic member (McClernand of Illinois) offered a resolution pledging the House to vote any amount of money and any number of men necessary to put down the rebellion and restore the authority of the Government. There were only five opposing votes in a House of nearly 300 members.

On July 21st the Union forces were badly defeated at Bull Run, and driven in a panic back upon Washington. For a moment this flight had the effect of disheartening the President. General Scott, who was commander-in-chief when the war broke out, resigned at the end of October, 1861, and Gen. George B. McClellan took his place. McClellan was a skillful tactician and organizer, but slow to strike. Lincoln realized the necessity for acting, but he had not yet gained the knowledge of war that he later acquired. His appointment of Edwin M. Stanton, a man not pleasing to him personally, as Secretary of War (January 14, 1862), was an evidence of great statesmanship, and Lincoln had trials that would have broken a weaker man. McClellan, after waiting and complaining unnecessarily, finally began a campaign in which he was thoroughly baffled by General Lee. In July Halleck was appointed general-in-chief of the armies of the United States. At the end of August the principal Federal force, under the command of Pope, was defeated in the second battle of Bull Run. On September 16th-17th McClellan met Lee in the bloody battle of Antietam in Maryland. This engagement was hardly decisive, but as the Confederates were forced to give up their invasion, Lincoln chose this moment to issue his proclamation, September 22, 1862, declaring that he would on January 1, 1863, emancipate the slaves of all the States then or thereafter in rebellion. This proclamation was a military measure justified as depriving the South to some extent of an advantage it enjoyed. Politically it was of the utmost importance, since it was the means of winning from the anti-slavery element throughout the North a more hearty support than had previously been accorded, and added greatly to the influence of the National Government abroad, where economic hardships threatened to conceal the fact that the war was being fought largely to vindicate a great moral principle. The support it received finally showed Lincoln to be right. Before this, though desiring emancipation, he had labored to persuade the border States to take the step of their own accord, in return for compensation, but he had been unsuccessful. Two years afterwards Lincoln said of the proclamation: “As affairs have turned it is the central act of my administration, and the great event of the nineteenth century.” McClellan failed to use his great force to follow Lee after Antietam; Burnside took command and was defeated at Fredericksburg: Hooker was appointed and suffered the disaster of Chancellorsville. Then the tide began to turn, and on July 4th, 1863, General Grant captured Vicksburg. At the same time Meade at Gettysburg beat off the second invasion of Lee and won a decisive victory. On November 19, 1863, Lincoln made his immortal speech on the dedication of the National Cemetery at Gettysburg. Meade having failed to follow up his victory over Lee, Lincoln, in March, 1864, complying with the recommendation of Congress, appointed Grant commander-in-chief. Ihe South was nearly worn out and Lee's superior generalship could not prevail against Grant's determination and unlimited resources. On April 9, 1865, Lee surrendered at Appomattox.

On November 8, 1864, Lincoln was reëlected over General McClellan by a vote of 212 to 21; Andrew Johnson was elected Vice-President. When Lee's surrender ended the war Lincoln was busy with plans for reconstruction, but on April 14, 1865, before he could do anything toward utilizing his wisdom in reorganization, he was shot in his box at Ford's Theatre by John Wilkes Booth, a dissipated and fanatical actor. The ball entered Lincoln's brain and he never regained consciousness. At 7 o'clock on the following morning he was dead.

The loss to the country by this death was incalculable, and the assassin injured most of all the people he would have served. The problem of bringing the two sections again into a union which should be more than one of force was as difficult as that of managing the war. To this problem Lincoln would have brought not only his experience, but generosity, utter lack of vindictiveness, incomparable tact, a tried strength which prevented vacillation. Lincoln's most marked characteristic was the accuracy with which he understood the American people. He was wholly honest; he thought fairly and never as a bigoted partisan. As a lawyer he was weak unless convinced of inherent right in his case, and when he was convinced he relied for victory on a skill in presenting facts which often set the other side in a light clearer than their attorneys could throw on their case. He conquered by the power of truth. This love for truth, his infinite patience, and his hard thinking seem to have guided him unerringly in every great problem he had to solve. He who had grown up in a drifting, almost illiterate, shiftless society, who had no education save that which he had been able to pick up in hours not devoted to bread-getting, who had been for years a mere country lawyer, with a narrow horizon, directed a foreign policy of dignity, strength, and honesty. Lincoln came of rough, shiftless, poverty-stricken stock, but through inexplicable gifts he wielded in a democracy and with the full consent of the people a power as great as that of the Czar. It was altogether fitting that a man of such charity should have the honor of doing most to free his country of slavery. This was his great achievement, but it must not he forgotten that events so great as the inception of the Pacific railroads and of the present national banking system belong to his administration. Some of the measures taken to repress Northern sympathizers with the South brought upon him harsh criticism, but these will probably be condoned by history, or at most condemned very tenderly. For the memory of the great martyr President is year by year held in more honor throughout the entire Union for which he gave his life.

Consult: Lives by Holland (Springfield, Mass., 1865); Lamon (Boston, 1872); Leland (New York, 1870); Arnold (Chicago, l885); by Herndon and Weik (3 vols., ib., 1889); by Nicolay and Hay (10 vols., New York, 1890); and an abridgment by Nicolay in 1902; Reminiscences by distinguished men of his time (New York, 1885); Morse in the “American Statesmen Series” (Boston, 1893); Hapgood (New York, 1899); and Tarbell (New York, 1900).