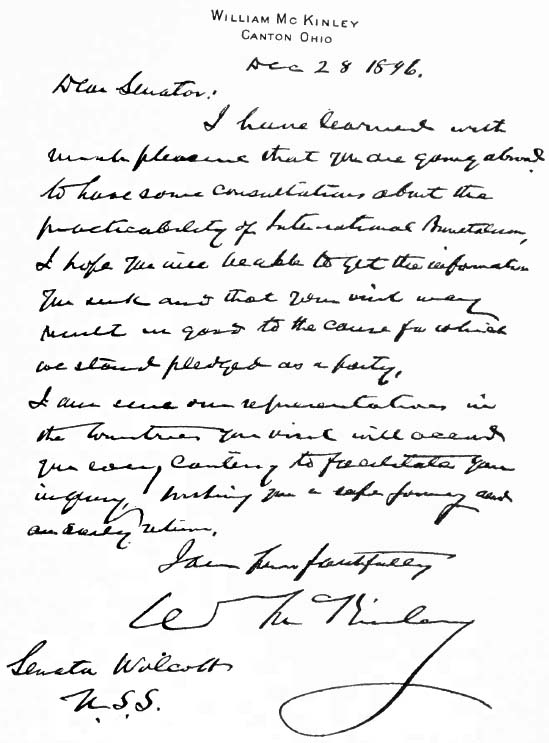

The Presidents of the United States, 1789-1914/William McKinley

WILLIAM McKINLEY

William McKinley, twenty-fifth president

of the United States, was born in Niles, Trumbull

county, Ohio, January 29, 1843. On his father's

side his ancestry is Scotch-Irish; his forefathers

came to America one hundred and fifty years ago.

Authentic records trace the McKinlays in Scotland

back to 1547, and it is claimed by students that

James McKinlay, “the trooper,” was one of

William's ancestors. About 1743 one of the Scotch-Irish

McKinleys settled in Chanceford township,

York county, Pa., where his son David,

great-grandfather of the president, was born in May,

1755. After serving in the revolution David

resided in Pennsylvania until 1814, when he went to

Ohio, where he died in 1840, at the age of eighty-five.

James McKinley, son of David, moved to

Columbiana county, Ohio, in 1809, when William,

father of the president, was not yet two years old.

The grandmother of the president, Mary Rose,

came from a Puritan family that fled from

England to Holland and emigrated to Pennsylvania

with William Penn. William McKinley, Sr.,

father

of the president, born in Pine township, Mercer

county, Pa., in 1807, married in 1829 Nancy

Campbell Allison, of Columbiana county, Ohio,

whose father, Abner Allison, was of English

extraction, and her mother, Ann Campbell, of Scotch-German.

Three of their nine children are now living,

William being the seventh. Both the grandfather

and the father of the president were iron

manufacturers, or furnace men. His father was a

devout Methodist, a stanch whig and republican,

and an ardent advocate of a protective tariff. He

died during William's first term as governor of

Ohio, in November, 1892. The mother of the president

died in December, 1897, at the age of

eighty-nine.

|

| Copyright by Pach Bros. |

William received his first education in the public

schools of Niles, but when he was nine years old the

family removed to Poland, Mahoning county,

Ohio, where he was at once admitted into Union

seminary and pursued his studies until he was

seventeen. He excelled in mathematics and the

languages, and was the best equipped of all the

students in debate. In 1860 he entered the junior class

of Allegheny college, Meadville, Pa., where he

would have been graduated in the following year

but for the failure of his health, owing to which, as

soon as he was able, he sought a change by engaging

as a teacher in the public schools. He was fond

of athletic sports, and was a good horseman. At

the age of sixteen he became a member of the

Methodist Episcopal church, and was noted for his

diligent study of the Bible. When the civil war

broke out, in the spring of 1861, he was a clerk

in the Poland post-office. Young McKinley

volunteered, and, going with the recruits to Columbus,

was there enlisted as a private in Company E, of

the 23d Ohio volunteer infantry, June 11, 1861.

This regiment is one of the most famous of Ohio

organizations, including an unusually large number

of noted men, among them Gen. W. S.

Rosecrans and President Hayes. He participated in all

the early engagements in West Virginia, the first

being at Carnifex Ferry, September 10, 1861, and

in the winter's camp at Fayetteville he earned and

received his first promotion, commissary sergeant,

April 15, 1862. “Young as McKinley was,” said

ex-President Hayes at Lakeside in 1891, “we soon

found that in business and executive ability he was

of rare capacity, of unusual and surpassing

capacity, for a boy of his age. When battles were

fought or a service to be performed in warlike

things, he always took his place.” At Antietam

Sergeant McKinley, when in charge of the

commissary department of his brigade, filled two

wagons with coffee and other supplies, and in the

midst of the desperate fight hurried them to his

dispirited comrades, who took new courage after

the refreshment. For this service he was promoted

from sergeant to lieutenant, his commission dating

from September 24, 1862.

While at Camp Piatt he was promoted to 1st lieutenant February 7, 1863, and under his leadership his company was first to scramble over the enemy's fortifications and silence their guns. Later, in the retreat that began on June 19, near Lynchburg, and continued until June 27, the 23d marched 180 miles, fighting nearly all the time, with scarcely any rest or food. Lieut. McKinley conducted himself with gallantry in every emergency, and at Winchester won additional honors. The 13th West Virginia regiment failed to retire when the rest of Hayes's brigade fell back, and was in imminent danger of capture. McKinley was directed to go and bring it away, if it had not already fallen, and did so safely, after riding through a heavy fire. “He was greeted by a cheer,” says a witness of the incident, “for all of us felt and knew one of the most gallant acts of the war had been performed.” During the retreat they came upon a battery of four guns which had been left in the way, an easy capture for the enemy. McKinley asked permission to bring it off, but his superior officers thought it impossible, owing to the exhausted condition of the men. “The 23d will do it,” said McKinley, and, at his call for volunteers, every man of his company stepped out, and the guns were hauled off to a place of safety. The next day, July 25, 1864, at the age of twenty-one, McKinley was promoted to the rank of captain. The brigade continued its fighting up and down the Shenandoah valley. At Berryville, September 3, 1864, Capt. McKinley's horse was shot under him.

After service on Gen. Crook's staff and that of Gen. Hancock, McKinley was assigned as acting assistant adjutant-general on the staff of Gen. Samuel S. Carroll, commanding the veteran reserve corps at Washington; where he remained through that exciting period which included the surrender of Lee to Grant at Appomattox and the assassination of Lincoln. Just a month before this tragedy, or on March 14, 1865, he had received from the president a commission as major by brevet in the volunteer U. S. army, “for gallant and meritorious service at the battles of Opequan, Cedar Creek, and Fisher's Hill.” At the close of the war he was urged to remain in the army, but, deferring to the judgment of his father, he was mustered out with his regiment, July 26, 1865, and returned to Poland. He had never been absent a day from his command on sick leave, had only one short furlough in his four years of service, never asked or sought promotion, and was present and active in every engagement in which his regiment participated. On his return to Poland with his old company, a complimentary dinner was given them, and he was selected to respond to the welcoming address, which he did with great acceptability.

He at once began the study of law under the preceptor ship of Judge Charles E. Glidden and his partner, David M. Wilson, of Youngstown, Ohio, and after a year of drill completed his course at the law-school in Albany, N. Y. In March, 1867, he was admitted to the bar at Warren, Ohio. On the advice of his elder sister, Anna, he settled in Canton, Ohio, where she was then and for many years after a teacher in the public schools. He was already an ardent republican, and did not forsake his party because he was now a resident of an opposition county. On the contrary, in the autumn of 1867 he made his first political speeches in favor of negro suffrage, a most unpopular doctrine throughout the state. Nominations on the republican ticket in Stark county were considered empty honors; but when, in 1869, he was placed on the ticket for prosecuting attorney he made so energetic a canvass that he was elected. He discharged the duties of his trust with fidelity and fearlessness, but in 1871 he failed of re-election by 45 votes. He thereupon resumed his increasing private practice, but continued his interest in politics, and his services as a speaker were eagerly sought. In the gubernatorial campaign between Hayes and Allen, in 1875, at the height of the greenback craze, he made numerous effective speeches in favor of honest money and the resumption of specie payments. Stewart L. Woodford, of New York, spoke at Canton that autumn, and on his return to Columbus Mr. Woodford made it a point to see the state committee and urge them to put McKinley upon their list of speakers. They had not heard of him before, but they put him on the list, and he was never taken off it after. The next year, 1876, McKinley was nominated for congress over several older competitors, on the first ballot, and was elected in October over Leslie L. Lanborn by 3,300 majority. During the progress of the canvass, while visiting the centennial exposition in Philadelphia, he was introduced by James G. Blaine to a great audience which Blaine had been addressing at the Union league club, and scored so signal a success that he was at once in demand throughout the country.

Entering congress on the day when his old colonel assumed the presidency, and in high favor with him, McKinley was not without influence even during his first term. On April 15, 1878, he made a speech in opposition to what was known as “the Wood tariff bill,” from its author, Fernando Wood, of New York. His speech was published and widely circulated by the republican congressional committee, and otherwise attracted much attention.

In 1877 Ohio went strongly democratic, and the legislature gerrymandered the state, so that McKinley found himself confronted by 2,580 adverse majority in a new district. His opponent was Gen. Aquila Wiley, who had lost a leg in the national army, and was competent and worthy. Not deterred, McKinley entered the canvass with great energy, and after a thorough discussion of the issues in every part of the district, was re-elected to the 46th congress by 1,234 majority. At the extra session, April 18, 1879, he opposed the repeal of the federal election laws in a speech that was issued as a campaign document by the republican national committee of that and the following year. As chairman of the republican state convention of Ohio, of 1880, he made another address devoted principally to the same issue. Speaker Randall gave him a place on the judiciary committee, and in December, 1880, appointed him to succeed President Garfield as a member of the ways and means committee. The same congress made him one of the house committee of visitors to West Point military academy,[1] and he was also chairman of the committee having in charge the Garfield memorial exercises in the house in 1881.

The Ohio legislature of 1880 restored his old congressional district, and he was unanimously nominated to the 47th congress. His election was assured, but he made a vigorous canvass, and was chosen over Leroy D. Thoman by 3,571 majority. He was chosen by the Chicago convention as the Ohio member of the republican national committee, and accompanied Gen. Garfield on his tour through New York, speaking also in Maine, Indiana, Illinois, and other states.

The 47th congress was republican, and, acting on the recommendation of President Arthur, it proceeded to revise the tariff. After much discussion it was agreed to constitute a commission who should prepare such bill or bills as were necessary and report at the next session. In the debate on this project McKinley delivered an interesting speech, April 6, 1882, in which, while not giving his unqualified approval to the creation of a commission, he insisted that a protective policy should never for an instant be abandoned or impaired.

The elections of 1882 occurred while the tariff commission was still holding its sessions, and the republicans were everywhere most disastrously defeated. The democracy carried Ohio by 19,000, and elected 13 of the 21 congressmen. McKinley had been nominated, after a sharp contest for a fourth term, and was elected in October by the narrow margin of eight votes over his democratic competitor, Jonathan H. Wallace. At the short session an exhaustive report by the tariff commission was submitted, and from this the ways and means committee framed and promptly introduced a bill reducing existing duties, on an average, about 20 per cent. McKinley supported this measure in an explanatory and argumentative speech of some length January 27, 1883, but it was evident from the start that it could not become a law, and the senate substitute was enacted instead. Although his seat in the 48th congress was contested, he continued to serve in the house until well toward the close of the long session. In this interval he delivered his speech on the Morrison tariff bill, April 30, 1884, which was everywhere accepted as the strongest and most effective argument made against it. At the conclusion of the general debate, May 6, 41 democrats, under the leadership of Mr. Randall, voted with the republicans to defeat the bill.

At the Ohio republican state convention of that year, 1884, McKinley presided, and he was unanimously elected a delegate at large to the national convention. He was an avowed and well-known supporter of Mr. Blaine for the presidency, and did much to further his nomination. Several delegates gave him their votes in the balloting for the presidential nomination. In the campaign he was equally active. The democrats had carried the Ohio legislature in 1883, and he was again gerrymandered into a district supposed to be strongly against him. He accepted a renomination, made a diligent canvass, and was again elected, defeating David R. Paige, then in congress, by 2,000 majority. But his energies were by no means confined to his own district. He accompanied Mr. Blaine on his celebrated western tour, and afterward spoke in the states of West Virginia and New York.

In the Ohio gubernatorial canvass of 1885 Major McKinley was equally active. His district had been restored in 1886, and he was elected by 2,550 majority over Wallace H. Phelps, the democratic candidate. In the state campaigns of 1881, 1883, and 1885, and again in 1887, he was on the stump in all parts of Ohio. In the 49th congress, April 2, 1886, he made a notable speech on arbitration as the best means of settling labor disputes. He spoke at this session on the payment of pensions and the surplus in the treasury, and both speeches merit attention as forcible statements of the position of his party on those questions.

Major McKinley delivered a memorial address on the presentation to congress of a statue of Garfield, January 19, 1886. He also advocated the passage of the so-called dependent pension bill, February 24, over the president's veto, as a “simple act of justice,” and “the instinct of a decent humanity and our Christian civilization.”

In accordance with Mr. Cleveland's third annual message, December 6, 1887, which attacked the protective tariff laws, a bill was prepared and introduced in the house by Mr. Mills, embodying the president's views and policy, and the two parties were arrayed in support or opposition. Then occurred one of the most remarkable debates, under the inspiration and encouragement of the presidential canvass already pending, in the history of congress. It may be classed as the opportunity of McKinley's congressional life, and never was such an opportunity more splendidly improved. Absenting himself from congress a few days, he returned to Canton December 13, 1887, and delivered a masterly address before the Ohio state grange on “The American farmer,” in which he declared against alien landholding, and advised his hearers to remain true to their faith in protection. He also went to Boston and discussed before the Home market club, February 9, 1888, the question of “free raw material,” upon which the majority in the house counted so confidently to divide their republican opponents, with such breadth and force that the doctrine was abandoned in New England, where it was supposed to be strongest.

On February 29 he addressed the house on the bill to regulate the purchase of government bonds, not so much in opposition to the measure, as because he believed that the president and the secretary of the treasury had been “piling up a surplus” of $60,000,000 in the treasury, without retiring any of the bonds, “for the purpose of creating a condition of things in the country which would get up a scare and stampede against the protective system.”

On April 2 he presented to the house the views of the minority of the ways and means committee on the Mills tariff bill. On May 18, the day the general debate was to close, McKinley delivered what was described at the time as “the most effective and eloquent tariff speech ever heard in congress.” The scenes attending its delivery were full of dramatic interest. The speaker who immediately preceded him was Samuel J. Randall, who had insisted on being brought from what proved his deathbed to protest against the passage of the proposed law. He spoke slowly and with great difficulty, and his time expiring before his argument was concluded, McKinley yielded to Randall from his own time all that he needed to finish his speech. It was a graceful act, and the speech that followed fully justified the high expectations that the incident naturally aroused. In it he showed that no single interest or individual anywhere was suffering either from high taxes or high prices, but that all who tried to be were busy and thrifty in the general prosperity of the times. In a well-turned illustration, at the expense of his colleague, Mr. Morse, of Boston, he showed, by exhibiting to the house a suit of clothes purchased at the latter's store, that the claims of Mills as to the prices of woollens were absurd. His refutation of some current theories concerning “the world's markets” and the effect of protective laws upon trusts was widely applauded. He held that protection was from first to last a contention for labor. Both congress and the country heartily applauded this speech. The press of the country gave it unusual attention, republican committees scattered millions of copies of it, and it everywhere became a text-book of the campaign.

McKinley was a delegate at large to the republican national convention of this year, and took an active part in its proceedings, as chairman of the committee on resolutions. He was the choice of many delegates for president, and when it was definitely ascertained that Mr. Blaine would not accept the nomination, a movement in his favor began that would doubtless have been successful had he permitted it to be encouraged. When during the balloting it was evident that sentiment was rapidly centering upon him, McKinley rose and said: “I can not with honorable fidelity to John Sherman, who has trusted me in his cause and with his cause; I can not consistently with my own views of personal integrity, consent, or seem to consent, to permit my name to be used as a candidate before this convention. . . . I do not request, I demand, that no delegate who would not cast reflection upon me shall cast a ballot for me.” The effect on the convention was as he intended. His labors for Sherman were incessant and effective, but while he could not accomplish his friend's nomination, he did preserve his own integrity and increase the general respect and confidence of the people in himself.

He was for the seventh time nominated and elected to congress in the following November, defeating George P. Ikert by 4,100 votes. At the organization of the 51st congress he was a candidate for speaker, but, although strongly supported, he was beaten on the third ballot in the republican caucus by Thomas B. Reed. He resumed his place on the ways and means committee, and on the death of Judge Kelley, soon afterward, became its chairman. Thus devolved upon him, at a most critical juncture, the leadership of the house, under circumstances of peculiar difficulty, his party having only a nominal majority, and it requiring always hearty concord and co-operation to pass any important measure. The minority had resolved upon a policy of obstruction and delay, but Major McKinley supported Speaker Reed with his usual effectiveness, and the speaker himself heartily thanked him for his great and timely assistance. On April 24, 1890, he spoke in favor of sustaining the civil-service law, to which there was decided opposition. “The republican party,” said he, “must take no step backward. The merit system is here, and it is here to stay.”

On December 17, 1889, he introduced the first important tariff measure of the session — a bill “to simplify the laws in relation to the collection of the revenue.” The bill passed the house March 5, and the senate, as amended, March 20, went to a conference committee, who agreed upon a report that was concurred in, and was approved June 10, 1890. It is known as the “customs administration bill,” is similar in its provisions to a bill introduced in the 50th congress, as the outgrowth of a careful, non-partisan investigation by the senate committee on finance, and has proved a wise and salutary law. Meanwhile (April 16, 1890) he introduced the general tariff measure that has since borne his name, and that for four months had been under constant consideration by the ways and means committee. His speech in support of the measure, May 7, fully sustained his high reputation as an orator. Seldom, if ever, in the annals of congress, has such hearty applause been given to any leader as that which greeted him at the conclusion of this address. The bill was passed by the house on May 21, but was debated for months in the senate, that body finally passing it on September 11, with some changes, notably the reciprocity amendment, which McKinley had unavailingly supported before the house committee. The bill, having received the approval of the president, became a law October 6, 1890.

The passage of the bill was hardly effected before the general election occurred, and in this the republicans were, as anticipated, badly defeated. His own district had been gerrymandered again, so that he had 3,000 majority to overcome. Never was a congressional campaign more fiercely fought, the contest attracting attention everywhere. His competitor was John G. Warwick, recently lieutenant-governor, a wealthy merchant and coal operator of his own county. McKinley ran largely ahead of his ticket, but was defeated by 300 votes. No republican had ever received nearly so many votes in the counties composing the district, his vote exceeding by 1,250 that of Harrison in the previous presidential campaign. Immediately after the election a popular movement began in Ohio for his nomination for governor, and the state convention in June, 1891, made him its candidate by acclamation. Meanwhile in congress he spoke and voted for the eight-hour law; he advocated efficient antitrust and antioption laws; he supported the direct-tax refunding law in an argument that abounds with pertinent information; and he presented and advised the adoption of a resolution declaring that nothing in the new tariff law should be held to invalidate our treaty with Hawaii. On the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the birth of Judge Thurman, at Columbus, in November, 1890, Mr. Cleveland spoke upon “American citizenship,” and “made cheapness the theme of his discourse, counting it one of the highest aspirations of American life.” Major McKinley, replying to this address at the Lincoln banquet in Toledo February 12, 1891, to the contrary held that such a boon as “cheap coats” meant inevitably “cheap men.”

At Niles, on August 22, he opened the Ohio campaign. In this speech, as in every other of the 134 made by him in that wonderful canvass, he declared his unalterable opposition both to free trade and free silver. The campaign was earnest and spirited; both he and his opponent, Gov. Campbell, made a thorough canvass, and met once in joint debate at Ada, Hardin county, in September. McKinley won a decisive victory, polling the largest vote so far cast for governor in the history of Ohio. Campbell had been elected in 1889 by 11,000 plurality in a vote of 775,000; McKinley now defeated him by 21,500 in a total of 795,000. His inaugural address, January 11, 1892, was devoted exclusively to state topics, except in its reference to congressional redistricting, in which he advised that “partisanship should be avoided.”

Soon after his inauguration as governor the presidential campaign began, and when importuned by friends to allow the use of his name as a candidate, he promptly replied that he believed Gen. Harrison justly entitled to another term. He was again elected a delegate at large from Ohio to the national convention, and was by it selected permanent chairman. He asked his friends not to vote for him, but urged them to support Harrison. Still, when the ballot was taken many persisted in voting for him, though his name had not been formally presented, the Ohio delegation responding 44 to 2 for him. He at once challenged this vote, from the chair, and put himself on record for Harrison, who on the entire roll call received 535 votes; Blaine, 182; McKinley, 182; Reed, 4; and Lincoln, 1. Leaving the chair, he moved to make the nomination unanimous, and it prevailed with out objection. He was chairman of the committee to notify the president of his renomination June 20, and from that time until the campaign closed was more busily engaged than perhaps any other national leader of the republican party. After the loss of the fight he gave up neither courage nor confidence. He had no apologies or excuses to offer. In responding to the toast “The republican party,” at the Lincoln banquet in Columbus, in 1893, he again manifested the same high spirit.

In his first annual message, January 3, 1893, Gov. McKinley called attention to the financial condition of the state, and enjoined economy in appropriations. His sympathy with laboring men is apparent in his recommendation of additional protection to steam and electric railroad employees, and his interest in the problems of municipal government by his approval of what is called the “federal plan” of administration. At the republican convention in Ohio he was unanimously renominated for governor, and he was re-elected by an overwhelming majority, the greatest ever recorded, with a single exception during the war, for any candidate up to that time in the history of the state — his vote aggregating 433,000 and his plurality 80,995. His competitor was Lawrence T. Neal. The issues discussed were national, and McKinley's voice was again heard in every locality in the state in earnest condemnation of “those twin heresies, free trade and free silver.” The country viewed this result as indicative of the next national election, and he was everywhere hailed as the most prominent republican aspirant for president. In his second annual message Gov. McKinley recommended biennial sessions of the legislature; suggested a revision of the tax laws by a commission created for the purpose; and condemned any increase of local taxation and indebtedness.

On February 22, 1894, McKinley delivered an address on the life and public services of George Washington, under the auspices of the Union league club, Chicago, which gave much gratification to his friends and admirers. Beginning at Bangor, Me., September 8, and continuing through the next two months, he was constantly on the platform. The Wilson-Gorman tariff law had just been enacted, and to this he devoted his chief attention. After returning to Ohio to open the state campaign at Findlay, Gov. McKinley set out for the west. Travelling in special trains, under the auspices of state committees, his meetings began at daybreak and continued until nightfall or later from his car, or from adjacent platforms. For over eight weeks he averaged seven speeches a day, ranging in length from ten minutes to an hour; and in this time he travelled over 16,000 miles and addressed fully 2,000,000 people.

During the ensuing winter there was great distress in the mining districts of the Hocking valley. Gov. McKinley, by appeals to the generous people of the state, raised sufficient funds and provisions to meet every case of actual privation, the bulk of the work being done under his personal direction at Columbus. Several serious outbreaks occurred during his administration, at one time requiring the presence of 3,000 of the national guard in the field. On three occasions prisoners were saved from mobs and safely incarcerated in the state prison. His declaration that “lynchings must not be tolerated in Ohio” was literally made good for the first time in any state administration.

On the expiration of his term as governor he returned to his old home at Canton. Already throughout the country had begun a movement in his favor that proved most irresistible in every popular convention. State after state and district after district declared for him, until, when at length the national convention assembled, he was the choice of more than two thirds of the delegates for president. In the republican national convention held in St. Louis in June, 1896, he was nominated on the first ballot, receiving 661½ out of 922 votes, and in the ensuing election he received a popular vote of 7,104,779, a plurality of 601,854 over his principal opponent, William J. Bryan. In the electoral college McKinley received 271 votes, against 176 for Bryan. The prominent issues in the canvass were the questions of free coinage of silver and restoration of the protective tariff system. Early in the contest he announced his determination not to engage in the speaking campaign. Realizing that they could not induce him to set out on what he thought an undignified vote-seeking tour of the country, the people immediately began to flock by the thousand to Canton, and here from his doorstep he welcomed and spoke to them. In this manner more than 300 speeches were made from June 19 to November 2, 1896, to more than 750,000 strangers from all parts of the country. Nothing like it was ever before known in the United States.

Besides the pilgrimages to Canton already

mentioned,

the canvass was marked by the fact that

Major McKinley's chief opponent, Mr. Bryan, was

the nominee of both the democratic and the populist

parties, and by the widespread revolt in the

democratic party caused by this alliance. Within

ten days after the adoption of the democratic platform

more than 100 daily papers that had been

accustomed to support the nominees of the democratic

party announced their opposition to both ticket

and platform, and Major McKinley was vigorously

supported by many who disagreed totally

with him on the tariff question. The campaign

was in some respects more thoroughly one of

education than any that had been known, and its closing

weeks were filled with activity and excitement,

being especially marked by the display of the

national flag. Chairman Hanna, of the republican

national committee, recommended that on the

Saturday preceding election day the flag should be

displayed by all friends of sound finance and good

government, and the democratic committee,

unwilling to seem less patriotic, issued a similar

recommendation. Thus a special “flag day” was

generally observed, and political parades of unusual

size added to the excitement. The result of the

contest was breathlessly awaited and received with

unusual demonstrations of joy.

On March 4, 1897, Major McKinley took the oath of office at Washington in the presence of an unusually large number of people and with great military and civic display. Immediately afterward he sent to the senate the names of the following persons to constitute his cabinet, and they were promptly confirmed by that body: Secretary of state, John Sherman, of Ohio; secretary of the treasury, Lyman J. Gage, of Illinois; secretary of war, Gen. Russell A. Alger, of Michigan; attorney-general, Joseph McKenna, of California; postmaster-general, James A. Gary, of Maryland; secretary of the navy, John D. Long, of Massachusetts; secretary of the interior, Cornelius N. Bliss, of New York; secretary of agriculture, James Wilson, of Iowa. Mr. Sherman was subsequently succeeded by William R. Day, of Ohio, and John Hay, of the District of Columbia; Elihu Root, of New York, was appointed secretary of war, to succeed Gen. Alger; John W. Griggs, of New Jersey, became the successor of Mr. McKenna in the office of attorney-general; Charles Emory Smith, of Pennsylvania, followed Mr. Gary as postmaster-general; Ethan Allen Hitchcock, of Missouri, was appointed to take the place of Mr. Bliss.

On March 6 the president issued a proclamation calling an extra session of congress for March 15. On that date both branches met and listened to a special presidential message on the subject of the tariff. The result was the drafting of the bill called “The Dingley bill,” after Chairman Nelson Dingley of the ways and means committee, and in the course of the summer this passed both branches of congress, and by the signature of the president became a law.

It was expected that the election of President McKinley would put an end to the hard times that had prevailed for many years in the country, which, as was believed, were due to the tariff policy of the Democratic party and to apprehension regarding the possible adoption of free coinage of silver. After the passage of the Dingley tariff bill there was a decided revival of prosperity. Many mills that had been closed resumed work, and there were other indications of returning confidence in the business world. On May 17 the president sent to congress a special message, asking for an appropriation for the aid of suffering Americans in Cuba, and in accordance therewith the sum of $50,000 was appropriated for that humane purpose.

The policy of the new administration toward Spain on the Cuban question had been a matter of much speculation, and there were those who expected that it would be aggressive. But it soon be came evident that it was to be marked by calmness and moderation. The president retained in office Consul-General Fitzhugh Lee, who had been appointed to his post by President Cleveland, although he sent a commissioner to Cuba to report to him on special cases; and the policy of the government in relation to the suppression of filibustering remained unchanged. Gen. Stewart L. Woodford, the new minister to Spain, was instructed to deliver to the Spanish government a message in which the United States expressed its desire that an end should be put to the disastrous conflict in Cuba, and tendered its good offices toward the accomplishment of such a result. To this message the Spanish government returned a conciliatory reply, to the effect that it had ordered administrative reforms to be carried out on the island, and expected soon to put an end to the unfortunate war, at the same time begging the United States to renew its efforts for the suppression of filibustering.

As was generally expected, the opening of the administration was marked by a fresh agitation of the question of Hawaiian annexation. A new treaty of annexation was negotiated and sent by the president to the senate, but action upon it was postponed. Meanwhile the Japanese government lodged a remonstrance against any such action on the part of the United States as might be deemed to prejudice the permanent rights alleged in favor of the Japanese under the terms of the treaty between Japan and the republic of Hawaii or adversely affect the settlement of the diplomatic dispute then pending in regard to the charged violation by Hawaii of the provisions of that treaty. The Japanese minister having disclaimed any ulterior unfriendly purpose of Japan, either in respect to the dispute or to the proposed annexation, the good offices of the United States were successfully employed with the Hawaiian republic to compose the controversy by the payment of a money indemnity to Japan, which amicably closed the incident before the final annexation of the islands to the United States. This was effected on August 12, 1898, by the act of the Hawaiian president in yielding up to the representative of the government of the United States the sovereignty and property of the Hawaiian islands, in accordance with the terms of a joint resolution of congress, approved July 7, 1898, whereby the purpose of the annexation treaty was accomplished by statutory acceptance of the offered cession and incorporation of the ceded territory into the Union.

A prominent incident in foreign affairs was a

despatch sent by Secretary Sherman to Ambassador

Hay regarding the Bering sea seal question,

which was criticised because of the recital of the

facts of the preceding award of the Paris Bering

sea commission and the discussion which followed

in order to show that Great Britain stood committed

to a revision of the Paris rules for the regulation

of seal-catching. On July 15 it was

announced that Great Britain had finally consented

to take part, with the United States, Russia, and

Japan, in a sealing conference in Washington in

the autumn of 1897; but later Lord Salisbury

declared that he had been misunderstood, and the

conference convened in November without British

delegates, although Sir Wilfrid Laurier, the Canadian

premier, was present unofficially. The passing

misunderstanding was speedily assuaged by the course

of the administration in sending a special ambassador

to Great Britain on the occasion of Queen

Victoria's diamond jubilee. For this purpose the president

selected Whitelaw Reid.

In the summer following the president's inauguration the reports of great gold discoveries on the Klondike river in British territory near the Alaskan boundary caused much excitement, recalling especially on the Pacific coast the days of the early California gold fever. So many expeditions set off almost at once for the north that the administration found it necessary to warn persons of the danger of visiting the arctic regions except at the proper season and with careful preparation; and to preserve order in Alaskan territory near the scene of the discoveries the president at once established a military post on the upper Yukon river. On April 7, in response to a message from the president asking relief for the sufferers by flood in the Mississippi valley, both houses of congress voted to appropriate the sum of $200,000 for this purpose. Much favorable comment was caused at the beginning of the administration by President McKinley's evident desire to make himself accessible to the public. On April 27, accompanied by his cabinet, he attended the ceremonies connected with the dedication of the Grant monument in Riverside park, New York. Immediately afterward he was present at the dedication of the Washington monument in Philadelphia.

President Cleveland, in his last annual message, had stated plainly the position of the United States on the Cuban question, saying that the suppression of the insurrection was essentially a matter for Spain, that this country would not fail to make every effort to prevent filibustering expeditions and unlawful aid of any kind for the rebels, but adding the warning note that there might come a time when intervention would be demanded in the name of humanity, and that it behooved Spain to end the struggle before this should become necessary. This was hardly a statement of party policy, but rather the expression of the sentiment of the whole country, and after the close of the first year of the new administration it was seen that its policy had been much along these lines. In his note of September 23, 1897, Gen. Woodford had assured the Spanish minister of foreign affairs, the Duke of Tetuan, that all the United States asked was that some lasting settlement might be found which Spain could accept with self-respect, and to this end the United States offered its kindly offices, hoping that during the coming month Spain might be able to formulate some proposal under which this tender of good offices might become effective, or else that she might give satisfactory assurances that the insurrection would be promptly and finally put down.

A change in ministry took place in Spain, and the liberals succeeded to power. The new foreign minister, Señor Gullon, replied to the American note on October 23, suggesting more stringent application of the neutrality laws on the part of the United States, and asserting that conditions in the island would change for the better when the new autonomous institutions could go into effect. This measure of self-government was proclaimed by Spain on November 23, 1897. The insurgents rejected it in advance; the Spanish Cubans who upheld Weyler's policy were equally vigorous in denouncing it; the remainder of the population was inclined to accept it, as it was in lieu of anything better, although it fell far short of what they had been led to hope for. It stipulated, among other things, that no law might be enacted by the new legislature without the approval of the governor-general; Spain was to fix the amount to be paid by Cuba for the maintenance of the rights of the crown, nor could the Cuban chamber discuss the estimates for the colonial budget until this sum had been voted first; furthermore, perpetual preferential duties in favor of Spanish trade and manufactures were provided for. The formal inauguration of the system took place in the beginning of January, 1898, but from the first it was evident that there were irreconcilable differences between the members of the ministry as well as between their followers, although there was manifested a certain well-wishing toward the new measure on the part of the insurgent party, many of them returning from the United States or coming from the field of hostilities to submit themselves under Marshal Blanco's proclamation of amnesty; yet early in January, 1898, the Spanish party broke out in such serious demonstrations and rioting against the autonomists and the Americans in Cuba that Consul-General Lee was induced to recommend the sending of an American man-of-war to Havana, as much for the moral effect of its presence as for the protection of American property there in the imminent and unfortunate contingency of disturbance.

The tone of the press in the United States had been growing more serious. The failure of the autonomous constitution was evident, the military situation was growing worse, the loss of life on the part of the helpless non-combatants caused by the reconcentration policy of Weyler was daily growing more appalling; it was clear that the whole situation was nearing a crisis. Señor Canalejas, the editor of a Madrid paper, made a journey to Cuba at this time to see the actual position with his own eyes. On his way he stopped in the United States, called on his friend Dupuy de Lôme, the Spanish minister at Washington, and then went on to Havana. Soon after the departure of Canalejas, de Lôme wrote him a private letter, in which he criticised severely the policy of the president in regard to the Cuban question, and characterized him as a vacillating and time-serving politician.

The letter was surreptitiously secured, and published widely in the press on February 8; later the original letter was communicated to the department of state. The following day, the 9th, Señor de Lôme admitted the genuineness of the letter in a personal conference with Assistant Secretary Day, stating that he recognized the impossibility of continuing to hold official relations with this government after the unfortunate disclosures, and adding that he had on the evening of the 8th, and again on the morning of the 9th, telegraphed to his government asking to be relieved of his mission. Immediately after this conference a telegraphic instruction was sent to Gen. Woodford to inform the government of Spain that the publication in question had ended the Spanish minister's usefulness, and expressing the president's expectation that he would be immediately recalled. Before Gen. Woodford could present this instruction, however, the cabinet had accepted the minister's resignation, putting the legation in charge of the secretary. Three days later Gen. Woodford telegraphed to the department a communication from the minister of state expressing the sincere regret of his government and entire disauthorization of the act of its representative. On February 17 Señor Polo y Bernabe was appointed to succeed Señor Dupuy de Lôme as the Spanish minister to the United States.

The excitement caused in the United States by this incident was still fresh when it was quickened into deeper and graver feeling by the destruction of the U. S. battle-ship “Maine” in the harbor of Havana. After the riots in January, 1898, Consul-General Lee had, as already stated, asked for an American man-of-war to protect the interests of this country. The Spanish authorities were advised that the government intended to resume friendly naval visits to Cuban ports; they replied, acknowledging the courtesy, and announcing their intention of sending in return Spanish vessels to the principal ports of the United States. The “Maine” reached Havana on January 25, and was anchored to a buoy assigned by the authorities of the harbor. She lay there for three weeks. Her officers received the usual formal courtesies from the Spanish authorities; Consul-General Lee tendered them a dinner. The sailors of the “Maine” were not given shore liberty owing to the ill-disguised aversion shown to the few officers who went ashore. The treatment of officers and crew by the Spanish authorities was perfectly proper outwardly, although no effusive cordiality was shown them.

At forty minutes past nine o'clock on the evening of February 15, while the greater part of the crew was asleep, a double explosion occurred forward, rending the ship in two and causing her to sink instantly. Out of a complement of 355 officers and men, 2 officers and 258 men were drowned or killed and 58 were taken out wounded. Capt. Sigsbee telegraphed a report of the occurrence to Washington, and asked that public opinion be suspended until further details were known. Marshal Blanco informed Madrid that the explosion was due to an accident caused by the bursting of a dynamo engine, or combustion in the coal-bunkers. The Queen Regent expressed her sympathy to Gen. Woodford, and the civil authorities of Havana sent messages of condolence, but no official expression of regret was then made by the Spanish government. When the naval court of inquiry reached Havana the local naval authorities offered to act with them in investigating the explosion, but the offer was declined. Thereupon Spain made an independent investigation. The conclusions of the American court of inquiry were that the explosion was not due to the officers or crew, but that it was caused by a submarine mine underneath the port side of the ship. The court found no evidence fixing the responsibility upon any person or persons. It was not until several weeks later, when the findings of the American court had been announced, and the heat of popular sentiment made war inevitable, that the Spanish government protested to Gen. Woodford against our ex parte investigation, alleging that a verdict so rendered was unfriendly, and asked that a joint investigation or else a neutral examination by expert arbitrators should be made to determine whether the explosion was due to internal or external causes. This proposal was declined by President McKinley. The investigation conducted independently by the Spanish government found that the explosion on the “Maine” was accidental and internal.

War was now only a question of time. On March 7 two new regiments of artillery were authorized by congress, and on March 9 $50,000,000 for national defence, to be expended at his discretion, was placed at the disposal of the president. This spectacle was remarkable, almost unique, was hailed with enthusiasm throughout the country and commanded widespread attention and admiration abroad. The speeches of Senator Proctor and others who had visited Cuba carried great weight. The president asked for a bill providing a contingent increase of the army to 100,000 men, which was passed at once. Spain on her part put forth every effort to re-enforce the army in Cuba and to strengthen the navy. On March 23, after the president had received the report of the naval court of inquiry, Gen. Woodford presented a formal note to the Spanish minister warning him that unless an agreement assuring permanent, immediate, and honorable peace in Cuba was reached within a few days the president would feel constrained to submit the whole question to Congress. Various other notes were passed in the next few days, but they were regarded by the president as dilatory and entirely unsatisfactory.

On April 7 the ambassadors or envoys of Great Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Austria, and Russia called on the president and addressed to him a joint note expressing the hope that humanity and moderation might mark the course of the United States government and people, and that further negotiations would lead to an agreement which, while assuring the maintenance of peace, would afford all necessary guarantees for the re-establishment of order in Cuba. The president, in response, said that he shared the hope the envoys had expressed that peace might be preserved in a manner to terminate the chronic condition of disturbance in Cuba so injurious and menacing to our interests and tranquillity as well as shocking to our sentiments of humanity, and while appreciating the humanitarian and disinterested character of the communication they had made on behalf of the powers, stated the confidence of this government for its part, that equal appreciation would be shown for its own earnest and unselfish endeavors to fulfil a duty to humanity by ending a situation the indefinite prolongation of which had become insufferable.

The Queen Regent directed that Gen. Blanco should be authorized to grant a suspension of hostilities, the form and duration being left to his discretion, to enable the insurgents to submit and confer as to the measure of autonomy to be granted to them. This was a very different thing from assent to the president's demand for an armistice from April to October, with an assurance that negotiations for independence should be opened with the insurgents. No real armistice being offered them, there was nothing for the Cubans to decline. It was this evasive outcome of the labors of the president for the past two months that caused him to abandon all hope of an adequate settlement by negotiation and to send in his message of April 11, which reviewed at length the negotiations and ended by leaving the issue with congress.

On April 13 a resolution was passed by the house authorizing the president to intervene to pacify Cuba. On April 16 the senate amended the house resolution by striking out all except the number, and substituting a resolution recognizing Cuba's independence. April 19 these two resolutions were combined in a joint resolution which was adopted by both houses, after a bitter struggle. This resolution was approved by the executive on the next day. Spain assumed to treat the joint resolution of April 20 as a declaration of war, and sent Gen. Woodford his passports about seven o'clock on the morning of the 21st, before he could communicate the demands of the resolution. In the United States it was assumed that by dismissing Gen. Woodford Spain initiated actual war, wherefore congress, by an act approved April 25, declared “that war exists and that war has existed since the 21st day of April, A.D. 1898, including said day, between the United States of America and the kingdom of Spain.” In like manner the Spanish decree of April 23 simply recites in article one “the state of war existing between Spain and the United States,” without assigning a date for its beginning. The president's proclamation of April 26 coincided with the Spanish decree of April 23 in adopting for the war the maritime rules of the declaration of Paris.

By the end of the month the troops called for under the act of April 23, authorizing the president to call for 125,000 volunteers, had begun to concentrate at Tampa, Fla. On April 30 congress authorized a bond issue of $200,000,000, and a circular was issued the same day inviting subscriptions. The total of subscriptions of $500 and less was $100,444,560, and the total in greater amounts than $500, including certain proposals guaranteeing the loan, amounted in the aggregate to more than $1,400,000,000.

The navy took the first steps in actual hostilities; orders for a blockade of Cuba were issued on April 21, and the blockade was established and proclaimed on April 22; in his proclamation of April 26 the president set forth at length the principles that would govern the conduct of the government with regard to the rights of neutrals and the other points of naval warfare. The nation had scarcely felt a realizing sense of the existence of war before there came news of Dewey's magnificent victory at Manila. This event, coming at a comparatively early date in the war, fired the national heart with great enthusiasm, and added immensely to the prestige of our navy abroad. The country's elation over such an unprecedented victory caused the people to wait with eager expectation for news from the operations in Cuban waters. On May 4 Admiral Sampson's squadron sailed from Key West; on the 12th it engaged the forts at San Juan de Puerto Rico. This was but a reconnoissance to discover whether or not the fleet under Admiral Cervera was in port; for the main object of the navy was to engage and destroy the Spanish fleet, which had left the Cape Verde islands on April 29. On May 19 Commodore Schley's flying squadron sailed from Key West for Cienfuegos. On the same day the navy department was informed of Cervera's presence at Santiago, and this information was transmitted to Commodore Schley at Cienfuegos through Admiral Sampson. Commodore Schley then proceeded to Santiago. Sampson joined Schley on June 1, and assumed command of the entire fleet.

Naval operations against Santiago had as a prelude the landing on June 10 of 600 marines, who intrenched themselves near the harbor of Guantanamo, and successfully repulsed repeated attacks by the Spaniards. The army that had been collecting at Tampa was now ready for action, and on June 14 Gen. Shafter with 16,000 men embarked for Cuba, under escort of 11 war-ships. The troops arrived off Guantanamo Bay on the 20th, and began landing on the 22d at Daiquiri, 17 miles east of Santiago, the entire army being disembarked by the 23d with only two casualties. The forward movement was begun at once; after a sharp action near La Quasima on the 24th, in which the Americans under Gen. Wheeler lost 16 killed and 52 wounded, came on July 1 the storming of the heights of El Caney and San Juan near Santiago. In the two days fighting at this point the loss for the U. S. troops was 230 killed, 1,284 wounded, and 79 missing. Gen. Shafter found Santiago so well defended that he feared he could take it only with a serious loss of life; he must have re-enforcements. The situation rested thus on the morning of July 3, but by night of the same day it had changed completely. On that morning Cervera, after peremptory orders from Gen. Blanco, ordered his fleet to sea from its sheltered position in the harbor. The blockading vessels closed in upon the Spanish ships immediately upon their appearance, following them closely as they turned in flight to the west, and by evening had sunk or disabled every one of them, losing but 1 man killed and 10 wounded, as compared with a loss to the enemy of about 350 killed and 1,670 prisoners.

On the morning of the 3d Gen. Shafter sent a flag of truce into Santiago, demanding immediate surrender on pain of bombardment. This was refused, but at the request of the foreign consuls Shafter agreed to postpone bombardment until ten o'clock on July 5. On the 5th, at a conference with Capt. Chadwick, representing Admiral Sampson, it was agreed that the army and navy should make a joint attack on the city at noon of the 9th. A truce was arranged until that date, when Gen. Shafter repeated his demand and the threat of bombardment. Unconditional surrender was refused, which the president demanded.

On the 10th and 11th firing went on from the trenches and the ships, and by evening of the latter day all the Spanish artillery had been silenced. A truce was arranged as a preliminary to surrender. Gen. Miles arrived at Gen. Shafter's headquarters on the 12th. Terms were finally settled on the 17th, when the U. S. troops took possession of the city. On the 21st Gen. Miles sailed with an expedition to Puerto Rico, where he landed on the 25th. His progress through the island met with little resistance, the inhabitants turning out to welcome the invading troops as deliverers. In less than three weeks the forces of the United States rendered untenable every Spanish position outside of San Juan; the Spaniards were defeated in six engagements, with a loss to the invaders of only 3 killed and 40 wounded, about one-tenth of the Spanish loss.

After the fall of Santiago it was evident at Madrid that further resistance was useless, and that a prolongation of the war would mean only more severe terms. On July 26 Jules Cambon, the French ambassador at Washington, was requested to inquire if peace negotiations might be opened. President McKinley replied to the note on the 30th, stating the preliminary conditions that the United States would insist upon as a basis of negotiations. A protocol of agreement was signed on August 12 by Secretary Day and Ambassador Cambon, in which the stipulations were embodied in six articles, fixing, besides, a term of evacuation for the West Indian islands, and settling October 1 following as the date of meeting of commissioners to settle the terms of peace between this country and Spain.

Now that the war was practically over, it became necessary to withdraw as many of the U. S. troops as possible from the unhealthy situation in Cuba. A camp was hastily provided at Montauk Point, Long Island, and hither the troops were hurried from Cuba. Suffering could not be avoided, of course, and from Camp Wikoff at Montauk Point, and from the twelve other chief army camps as well as the smaller ones, went up a cry that the troops were not receiving the careful attention they deserved. President McKinley made a personal visit to Montauk Point in August to satisfy himself as to the actual state of affairs. In September he appointed a commission to investigate the charges of criminal neglect of the soldiers in camp, field, hospital, and transport, and to examine the administration of the war department in all its branches. The commission met first on September 27, sat in many places, and heard witnesses in city and camp. Gen. Miles, in his testimony, described the beef furnished the troops as “embalmed,” and in reply on January 12, 1899, Commissary-Gen. Eagan denied the charge, and made such a bitter personal attack upon Gen. Miles that the president ordered his trial by court-martial, with the result that he was found guilty of conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, and sentenced to dismissal from the army. This was commuted by the president on February 7 to suspension for six years. The commission made its report on February 8, and on February 9 an army court of inquiry was appointed by the president to investigate the charges of Gen. Miles in relation to the beef-supply. The court found that the allegations were not sustained.

On August 26 President McKinley appointed William R. Day, Cushman K. Davis, William P. Frye, Whitelaw Reid, and George Gray as peace commissioners. John Bassett Moore was appointed secretary and counsel. The commissioners met the Spanish commissioners in Paris on October 1. Negotiations continued until December 10, when the treaty was signed. It provided for the relinquishment by Spain of all claims of sovereignty over and title to Cuba; the cession of all other Spanish West India islands, and of Guam in the Ladrone group; the cession of the Philippines to the United States, and the payment to Spain by the United States of $20,000,000 within three months after the exchange of ratifications of the treaty; Spanish soldiers were to be repatriated at the expense of the United States. Other details settling property rights were also included; ratifications were to be exchanged at Washington within six months, or earlier, if possible. The commissioners returned to the United States late in December, and submitted the official text of the treaty to the president, who retained it for consideration until January 4, 1899, and then transmitted it to the senate, where it was at once referred to the committee on foreign relations. In his annual message to congress on December 5 the president had contented himself largely with a simple narrative of events that led up to the war, suggesting his own theory as to its causes, and deferring all discussion of the future government of the new territories until after the ratification of the treaty of peace. The President recommended also careful consideration of the provisions suggested by Secretary Alger and Mr. Hull, chairman of the house committee on military affairs, for the enlargement of the regular army. The president was given opportunity to impress his views upon the country less formally, but none the less effectively, in his speeches and addresses on his trip to the Omaha Exposition in October and visit to the Atlanta peace jubilee during December, 1898. Nevertheless, there were anxious weeks of waiting after the treaty had been given to the senate for consideration, weeks in which little was certain, except that there was a strong, forceful opposition in that body to its ratification, urged on by various motives, but nevertheless united sufficiently to make the friends of the treaty anxious for its fate, and, to the relief of the president and the country, the treaty was duly ratified. It is not probable that the war in the Philippines, precipitated by the night attacks of the insurgents upon the U. S. forces on February 4, had any great weight in influencing the voting upon the treaty; there can be little doubt, however, that the insurgent leaders, ignorant of the real feelings of the people at large, did draw encouragement for themselves from the reports of opposition to the treaty.

The question of peace with Spain once settled, the outbreak in the Philippines opened a new problem to the president. Anxious for information on the situation in those islands, he had appointed in January a commission of five, consisting of Admiral Dewey, Gen. Otis, President J. G. Schurman, of Cornell, Prof. Dean C. Worcester, of the University of Michigan, and Col. Charles Denby, for many years U. S. minister to China, to study the general situation in the Philippines and to act in an advisory capacity. In this step the president had shown his desire to act only upon ample information. When actual hostilities broke out, however, there was left to him but one thing to do: the insurrection must be put down. For this reason he gave Gen. Otis, in his policy of vigorous action, all the support possible.

Another difficulty for his solution arose in the condition of affairs in the Samoan islands. After the death in 1898 of Malietoa, King of Samoa, a struggle for the succession took place in the islands between the followers of Mataafa and of young Malietoa. For ten years Germany, Great Britain, and the United States had exercised joint control over the islands. This position of the three powers, coupled with the continuous fighting among the natives, seemed to promise a serious problem for the president, but by perfect coolness and uniform good judgment he brought the matter to a satisfactory issue. On the proposal of Germany, each of the three powers appointed one member of a commission to visit the islands and to investigate the entire question, beginning with the return of Mataafa and the election of 1898. Bartlett Tripp was appointed by the United States, Baron Speck von Sternberg by Germany, and C. N. E. Eliot by Great Britain. The commission unanimously recommended the abolition of the kingship and radical changes in the administration of Samoa. The three powers, however, recognizing the inexpediency of continuing any tripartite government of the islands, agreed upon an arrangement by which England retired from Samoa in view of compensation made by Germany in other quarters, and both powers renounced in favor of the United States all their rights and claims to the islands east of 171°, including Tutuila, with the fine harbor of Pago-Pago.

The president's appointments for the delegation to represent the United States at the peace conference called by the czar of Russia in 1898, which assembled at The Hague in May, 1899, were most favorably received. The delegation consisted of Andrew D. White, ambassador at Berlin; Stanford Newel, minister to Holland; Seth Low, president of Columbia university; Capt. Alfred T. Mahan, U. S. navy (retired); and Capt. William Crozier, U. S. army. Frederick W. Holls, of New York, was appointed secretary.

Of domestic events in the latter months of the first half of 1899 one of the most important was the order of May 29, in which the president withdrew a number of places in the civil service of the government from the operation of the system of appointment on the result of examinations conducted by the civil service commission. The president found a strong supporter and defender in the secretary of the treasury, who contended that the order was a beneficial step for the reform of the civil service; that only those positions had been exempted that experience had shown could be filled best without examination, and that the change had not been made in the slightest degree at the instance of the spoilsmen. The president and Mrs. McKinley spent the summers of 1897 and 1899 at a popular resort on Lake Champlain, and in August of the latter year the president made an eloquent address at the Catholic summer school, Cliff Haven, N. Y., in the course of which, referring to the condition of affairs in the Philippine islands, he said: “Rebellion may delay, but it can never defeat the American flag's blessed mission of liberty and humanity.” Later, at the Ocean Grove Assembly, New Jersey, McKinley remarked: “There has been doubt expressed in some quarters as to the purpose of the government respecting the Philippines. I can see no harm in stating it in this presence. Peace first, then, with charity for all, the establishment of a government of law and order, protecting life and property, and occupation for the well-being of the people, in which they will participate under the Stars and Stripes.” The president's message to congress in December, 1899, was cordially received and very generally commended throughout the country.

During the year 1900 the volume of currency per capita was the greatest in the history of the nation; the total money of the country on September 1 amounted to over two billions and ninety-six millions of dollars. Industrial and agricultural conditions advanced in prosperity in every section of the United States. Under these benign conditions the nation had also become a money-lending instead of a money-borrowing country. The national and international questions which arose during the year were of a most serious nature, but were solved by President McKinley and his cabinet with unusual sagacity, and with results of the highest importance to the United States and to the world at large.

The original Philippine commission, headed by President Jacob G. Schurman, submitted its full report on January 31, 1900. On February 6 President McKinley selected Judge William H. Taft to head a new commission, which was completed by March 16, and reached Manila on June 3. The laborious endeavors of the Taft commission began to bear fruit, and on September 1, under its direction, civil government was inaugurated in the archipelago. A vital death-stroke was dealt the insurrectionists by the capture of the rebel dictator, Aguinaldo, in March, 1901, by Gen. Funston and a small band of men, who achieved success through stratagem and disguise.

Early in the summer of 1900 the civilized world was startled by news that the foreign legations at Pekin, China, were besieged by an angry horde of celestials. A secret society, commonly known as “Boxers,” determined upon the extermination of all foreigners in the Chinese empire. For a time wild reports were current that the entire legations and their charges had been massacred. On July 20 the first official news to the contrary was received at Washington from United States Minister Conger. Europe doubted its authenticity, but further developments showed it to be genuine. The events which began with the destruction of the forts at Taku and ended with the capture of Pekin by the allied forces of Europe and the United States in August are a matter of contemporary history, in the making of which President McKinley and the United States played a conspicuous part. The president's moral influence for justice and fairness to China in her difficulties, resulting from the rashness of her misguided rulers and people, has been second to none among the leaders of the world's great nations.

Among the more important measures which Mr. McKinley forwarded during 1900 and early in 1901 the following may be mentioned: An established government for Porto Rico and the Philippines; the redemption of the pledge of the United States to Cuba for the inauguration of independent civil rule in the island; a reorganization of the army of the United States; extension of the American merchant marine; the construction of the Nicaragua Canal; and the signing of reciprocity treaties with various European powers.

At the Republican National Convention which was held in Philadelphia in June, 1900, President McKinley was unanimously renominated for a second term, and Theodore Roosevelt, then governor of New York, was likewise nominated unanimously for the vice-presidency. Their Democratic opponents were, respectively, William Jennings Bryan and Adlai E. Stevenson. At the election on November 6 the Republican candidates were elected, having carried twenty-eight states with 292 electoral votes. Their plurality of the popular vote was nearly a quarter of a million greater than in 1896. The members of the cabinet were all reappointed, but in March, 1901, Mr. Griggs resigned, and was succeeded by Philander C. Knox, of Pennsylvania as attorney-general. On April 29, accompanied by Mrs. McKinley, his cabinet, and other officials, the president left Washington on an excursion to the Pacific coast via New Orleans. On the day following, speaking at Memphis, Mr. McKinley said:

“What a mighty, resistless power for good is a united nation of free men! It makes for peace and prestige, for progress and liberty. It conserves the rights of the people and strengthens the pillars of the government, and is a fulfillment of that more perfect union for which our Revolutionary fathers strove, and for which the constitution was made. No citizen of the republic rejoices more than I do at this happy state, and none will do more within his sphere to continue and strengthen it. Our past has gone into history. No brighter one adorns the annals of mankind. Our task is for the future. We leave the old century behind us, holding on to its achievements and cherishing its memories, and turn with hope to the new, with its opportunities and obligations. These we must meet, men of the South, men of the North, with high purpose and resolution. Without internal troubles to distract us or jealousies to disturb our judgment, we will solve the problems which confront us untrammeled by the past, and wisely and courageously pursue a policy of right and justice in all things, making the future, under God, even more glorious than the past.”

Early in the autumn of 1901 the president, accompanied by Mrs. McKinley and several members of his cabinet, visited the Buffalo (N. Y.) exposition. On Thursday, September 5, he delivered an address embodying the ripest wisdom of his long and prosperous political career. It gathered together the experience of his many years of service to the country, and announced in clear, strong language the policy which was to guide him in the future, and which his successor afterward publicly adopted as his own. The speech is not merely an expression of the personal views of the president, however statesmanlike these may be; it is more than that; it is a sound statement of the actual problems involved in the new position which, under his own wise guidance, our country has assumed in the world. It is in a sense Mr. McKinley's legacy to his native land, and as such it should be appreciated and preserved by every patriotic American. On Friday afternoon, in the music hall of the exposition, while receiving his fellow-citizens, he was twice shot by an assassin, who was executed for the crime during the following month. The president lingered until early on Saturday morning, September 14. Funeral services were held in Buffalo, and on Thursday, September 19, which was by President Roosevelt appointed a day of mourning and prayer throughout the United States. On that day the body lay in state in the national Capitol, and was followed by a public funeral. At the same time unprecedented honors were paid to the memory of McKinley in St. Paul's Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, London, as well as in other parts of the Old World. The dead president's body was temporarily laid to rest in Canton, Ohio, where his widow resided. Probably none of his predecessors during their terms of office enjoyed as great popularity as William McKinley, and it may be safely asserted that the death of no other president was more universally mourned among his countrymen. A noble national monument was erected to his memory in Canton September 30, 1907, and was dedicated in the presence of President Roosevelt and several members of his cabinet.[2] See “Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley,” compiled by Joseph P. Smith (New York, 1893); the “Life of Major McKinley,” by Robert P. Porter (Cleveland, 1896); and “Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley, from 1897 to 1901” (New York, 1900).

|

| Charles Henry Niehaus, Sculptor |

MEMORIAL TO WILLIAM McKINLEY, CANTON, OHIO. DEDICATED SEPTEMBER 30, 1907

Major McKinley married, January 25, 1871,

Miss Ida Saxton, daughter of James A. and

Catherine Dewalt Saxton. Her grandparents were

among the founders of Canton; her father was a

banker, who, after giving his eldest daughter many

advantages of education and travel, began her business

training as cashier in his bank, that she might

be fitted for any change in fortune. Two daughters

were born to them, but both died in early childhood.

Mrs. McKinley's health, not robust at any

time, never completely rallied from these deaths in

quick succession. Although not strong, she successfully

discharged the social obligations demanded by

her position and her husband's prominence in public

affairs. She died May 26, 1907.

- ↑ Conversing with Congressman McKinley at West Point when they were members of the Board of Visitors in June, 1880, the writer mentioned that Gen. Winfield Scott was six feet four inches, just Lincoln's height, but almost a hundred pounds heavier, and McKinley remarked: “Lincoln, Washington, Jefferson and Jackson, all over six feet, were, I believe, in the order named, our four tallest Presidents, while I think Madison and Van Buren were the two shortest,” adding, “John Adams lived the longest of any of our chief magistrates, having died in his ninety-first year.” — Editor.

- ↑ The author of the original article, who was chosen by President McKinley, having died in February 1898, the additions covering the period after that date and some earlier were made by the editor of this work.