The Primeval Antiquities of Denmark/Second Division

SECOND DIVISION.

OF STONE STRUCTURES, BARROWS, &C.

To obtain correct ideas on the subject of the first peopling and the most ancient relations of our native country, it will not be sufficient to direct attention exclusively to objects exhumed from the earth. It is at the same time indispensably necessary to examine and compare with care the places in which antiquities are usually found; otherwise many most important collateral points can either not be explained at all, or at least in a very unsatisfactory manner. Thus we should scarcely have been able to refer, as we have done in the previous pages, the antiquities to three successive periods, if experience had not taught us that objects which belong to different periods are usually found by themselves. It is not however all places where objects are discovered which will here be treated of in a similar manner. For instance a great number of antiquities are found in peat-bogs, but who could safely maintain that such articles had lain there ever since the period when they were generally used, and have not been mingled at a later period with more modern objects lost or thrown in there. It will not be the places where antiquities may be casually met with, but rather our ancient stone structures and barrows, which, with reference to the subject just mentioned, ought to be the subject of a more particular description; for as to the graves themselves we know that, generally speaking, they contain both the bones of the dead, and many of their weapons, implements, and trinkets, which were buried with them. Here we may therefore, in general, expect to find those objects together which were originally used at the same period. The barrows serve to explain in various other ways the associations of pagan antiquity. They afford the surest guides to a knowledge of funeral ceremonies which gradually became dissimilar to each other, and since they are fixed and lasting memorials which may be destroyed altogether, but cannot be transferred from their original place, their situation and extension furnish us with very important testimony as to the most ancient settlement and occupancy of different districts. From a single mound standing by itself, we must not of course attempt to deduce too much, but by comparing a number of observations from all parts of the country, we arrive, by degrees, at a knowledge of the general and particular characteristics of the grave, and by this mean learn to refer the different kinds to distinct classes, and in some measure to distinct periods. Experience of this kind is of high value and importance. For, to cite an example, if we can prove that there exist in certain districts, barrows and structures of stone of the same form and the same contents, and that, beyond these districts, other and opposite relations exist, we certainly have a valid reason for concluding that such districts were inhabited in ancient times either by the same races of men, or at all events by races very nearly related.

The barrows of Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, like the antiquities of these countries, were at an earlier time all considered as belonging to one class, so that monuments of the most different kind were mixed together, as if they belonged to one period. For this reason we will just point out very briefly the chief classes of the acknowledged Danish monuments, and afterwards examine their connection with the ancient remains which exist in other parts of the North.

The Danish grave-hills are, like the early antiquities, generally divisible into three classes, namely, those of the stone, of the bronze, and that of the iron-period, which last includes the inscribed monumental stones, or Runic stones, as they are termed.

GRAVES OF THE STONE-PERIOD, OR CROMLECHS, (STEENDYSSER.)

The important and highly ancient memorials which are usually termed Cromlechs in England, Steingräber in Germany, and often Urgräber, (ancient graves, or Hünengräber, giants' graves,) are slightly elevated mounds surrounded by a number of upright stones, on the top of which are erected chambers formed of large stones placed one upon the other. Although many of them have been removed or destroyed for the sake of the stones, they still exist in Denmark in very considerable numbers. They are most frequently met with on the coast, particularly on the north and west coast of Seeland, on the coasts of Fühnen, in the north of Jütland at the Lümfiord, particularly in the domain of Thisled, as well as along the east coasts of Jütland, Sleswig, and Holstein. They occur more rarely on the west coasts, and still more seldom in the interior of the country. They may be divided into two chief kinds; 1st the long, and 2nd the small round Cromlechs, (Langdysser og Runddysser.) The term Cromlech is here applied not only to the stone chamber, but to the whole monument. As the long cromlechs (one of which we here figure as it is seen sideways) exist in great quantities in various districts of the country, their size is naturally very different. For the most part they are from sixty to a hundred and twenty feet in length, occasionally somewhat smaller, but there are instances of their being two hundred, and in some few cases four hundred feet in length. Their breadth on the other hand is very inconsiderable, at most they are only from sixteen to twenty-four, and the very longest of all thirty to forty feet.

No general rule can be stated as to the direction in which they lie. They are most frequently met with from east to west, they also lie from south to north, and from north-east to south-west. The aborigines do not seem to have confined themselves to any precise rule in the erection of such monuments.

Peculiar care and industry have been bestowed on enclosing these elevations with large stones. Occasionally one descries above a hundred colossal blocks of stone, set round the foot of a hill in an elongated circle, and this too in districts where not only in the present day, but also without a doubt in ancient times, there was a deficiency of such stones. There are also traces in some instances of the hill having been originally surrounded with two or more large enclosures of stone.

The stone chambers[1] erected on the summit of these mounds of earth are formed of a roofing or cap-stone which rests on several supporting stones placed in a circle.

The cap-stone is often from thirty to forty feet in circumference, and eight to ten feet in length, the side of it which is turned underneath, and forms the roof of the chamber, has always a smooth flat surface, while the side turned uppermost is almost always of a very irregular form. The supporting stones are also flat only on the side which is turned to the chamber. They commonly fit close to each other, the small openings which, from the nature of the material, may occur between them, being stopped up with flat pieces of stone placed one upon the other. The usual height of the supporting stones is from six to eight feet, and their breadth from two to three feet; their number depends on the height of the chamber; they are usually from four to five, but occasionally about fifteen have been met with in one of those structures; whence it follows that such a chamber must have had more than one roofing stone. The floor of the chamber itself is paved partly with flat stones, and partly with a number of small flints which appear to have been exposed to a very powerful heat. The chambers are either quite round, from five to seven feet in diameter, or they are oval and from twelve to sixteen feet in length, or they are merely formed of their supporting stones, so placed, that the two longest form the side walls and the shortest the cap-stone at the end.

Entrances of regular form, enclosed with blocks of stone, provided with a roof, and leading to the chambers of the long cromlechs, are very rare and are met with only in the largest of them. There is in general an opening between two of the supporting stones, which is sometimes indicated externally by two flat stones placed upright, or occasionally by a row of stones placed along the side of the hill and leading to such entrance. Like the hill itself there is no rule as to the direction in which it is placed; in most cases it has a direction south and east, and occasionally south-east, south- west, and north.

The most important of these monuments are the long-cromlechs, which consist of three chambers, a large one in the middle and a small one at each end. Stone structures with two chambers occur most frequently and present no particular form. On the other hand it is very remarkable that in those which have but one chamber, it is usually placed at one end, even when the barrows are of considerable length. Thus at the Clelund field in the district of Lindknud, in the domain of Ribe, there exists a stone enclosure which is about three hundred and seventy feet in length, in which however the stone chamber is situated only forty feet from the south-west end.

A great number of these chambers have been opened and explored, probably in most cases by persons who hoped to find great treasure in them. They are therefore frequently found quite exposed, although originally they were no doubt covered with earth, yet only in such a manner as to leave a portion of the stones which formed the roof visible. Of these cromlechs there are many still remaining. The chambers formed the regular place of interment, in which several bodies probably of the same family were deposited. We are not however to conceive that the space was ever left empty. As soon as a corpse had been deposited in it, it appears to have been filled with earth or clay and pebbles firmly trodden down, and not to have been opened until a new corpse was to be interred. In examining such sepulchral chambers as have remained undisturbed until the present time, it has been ascertained that they always contained the skeletons of one or more bodies, together with arrow-heads, lances, chisels, and axes of flint, implements of bone, ornaments of amber or of bone, and earthen vessels filled with loose earth. Even in the chambers which now remain open, and bear evident traces of having been before explored, we meet, on thorough investigation, with pieces of earthen vessels, single stone implements, and human bones, which plainly shew that these chambers do not preserve their original form, but that they were applied to the same purpose as those which are still partially covered with earth.

The small circular cromlechs differ from those above de- scribed only in the circumstance that the elevations are much smaller, and usually comprise but one chamber, which however with reference to its size is seldom inferior to the chambers of the oblong cromlechs[2]. At the same time it has been observed that the cap-stones of the small round cromlechs usually rest on five supporting stones.

The round cromlechs have been preserved in greater number than those previously described, but it is evident that they have been erected solely for the same purposes. Excavations have led to exactly the same results[3], since the chambers of the small cromlechs likewise contain unburnt human bones, articles of stone and amber, as well as earthen vessels[4]. As the mounds on which they are raised were

considerably smaller than those of the long graves, and therefore easier to remove, the chambers in most cases are either accessible or open altogether. But even in the floor of these we constantly find either very ancient graves but slightly disturbed, or undoubted remains of these, as human bones, broken vessels of clay, and objects of stone and amber.

We have already mentioned in the Introduction that the erroneous opinion which regarded the stone utensils as sacrificial instruments, also transformed cromlechs, and the hills on which they were constructed, into places of judgment, altars of sacrifice, and sacred abodes of the gods. The idea that the antiquities of stone were instruments of sacrifice is now indeed pretty generally rejected, but the opinion that the cromlechs raised by our forefathers were intended for places of judgment, or for altars, is still occasionally maintained. It will therefore be necessary to enquire further, as briefly as possible, how far that opinion may be well founded.

The idea entertained is as follows; the long cromlechs were places of worship at which the people assembled to consult on their common affairs, to decide differences, &c. &c.; on the large surrounding stones sat the judges and the elders of the people, and sacrifices were offered to the idols on the chambers of stone or altars. These sacrifices, it is thought, were conducted as follows: the victim was placed on the roof of the stone chamber, and when slain, the blood, from which the sacrificing priest derived his auguries, flowed into the chamber or opening under the cap-stone.

A cursory glance at the exterior arrangement of the cromlech will, it is conceived, suffice to shew that it is as utterly unfit for a place of judgment, (since the surrounding blocks of stone could never have afforded suitable seats,) as it is for an altar. If we adopt the latter supposition, the cap-stones must be sufficiently flat to admit of the animals intended to be sacrificed resting upon them. It is however a rule, without exception, that the flat side, instead of being uppermost, is invariably turned towards the chamber; beside which, we have also seen, that, with the view of guarding the chamber and its contents, the supporting stones were placed close to each other, while the interstices were filled with fragments which rendered it perfectly impossible for the blood of the sacrifice to flow from the cap-stone into the chamber. Again, the situation in which the cromlechs are met with plainly shews that they were neither altars nor seats of justice. They are found chiefly on the coast and in distinct districts; for instance in the parish of Rachlov near Kallundborg there are more than a hundred of these long and round cromlechs, while in Jellinga and other well-known parishes of very remote antiquity we do not meet with a single monument of this kind, a fact which is quite inconsistent with the idea of such monuments being altars or places of judgment. Moreover, it would be extremely singular if the first Christians, who sought with so much zeal to destroy every trace of heathenism, should have allowed these offensive altars of sacrifice to have been preserved. Let us add, that these altars, as they are termed, never occur either in Norway or in the northern part of Sweden, where paganism prevailed until the latest period; and finally, that, in general, human bones and funereal objects are exhumed from them, so that we can safely maintain that they are merely graves appertaining to the most ancient time, and that for this reason they usually occur on the coast.

GIANT' CHAMBERS (JÆTTESTUER.)

The view here expressed as to the origin and nature of the cromlechs acquires greater force and clearness from the circumstance that stone chambers perfectly corresponding to these, but on a somewhat larger scale, are frequently discovered, forming places of interment within large barrows of earth raised by the hands of man. These tombs, covered with earth, have perhaps contained the remains of the powerful and the rich. They are almost all provided with long entrances which lead from the exterior of the mound of earth to the east or south side of the chambers. For this reason it has been proposed to call these structures "passage buildings," (Gang bygningen). The entrances, like the chambers, are formed of large stones, smooth on the side which is turned inwards, on which very large roof-stones are placed. As a single chamber is therefore formed of a considerable number of heavy masses of stone, which would be extremely difficult to set up, independently of placing them on one another, it is highly probable that the name of "Giants' Chambers" may have had its origin in the opinion of the lower classes, that the giants (jætter) who, according to the Sagas, could with ease hurl enormous rocks, were alone able to execute such stupendous works[5].

The giants' chambers, like the chambers of the cromlechs, are round or oval. In those tumuli which contain round chambers, two such have several times been found near each other, each with a separate entrance. Those which are circular are from five to eight feet in diameter, and about that height. A grown man can usually stand upright in the apartment, when the earth with which it is filled is removed. For these chambers, and even the entrances, which are from sixteen to twenty feet in length, are filled with trodden earth and pebbles, the object of which doubtless was to protect the repose of the dead in their grave. The same objects are discovered in these giant chambers as are found in the cromlechs, namely, unburnt skeletons, which were occasionally placed in sand on a pavement of flat or round stones, together with implements and weapons and tools of flint or bone, ornaments, pieces of amber, and urns of clay. Skeletons are also occasionally found deposited in the passages leading to the giant chambers; a circumstance which may be explained by supposing that such giant chambers were sometimes family burial-places, which were filled as the members of the family died: and that when the chambers themselves could contain no more bodies, recourse was necessarily had to the entrance. That these giant chambers have been opened, from time to time, is evident from the fact that in general they are found to contain a quantity of fragments of broken pottery, which had been broken at some remote period.

The largest and most considerable of the giants' chambers are the long ones, which are from sixteen to twenty-four feet in length and from six to eight feet in breadth[6]. The en- trance is generally about twenty feet long. By some writers they are styled by the less striking epithet of semi-cruciform graves.

With reference to their contents and their general arrangements they entirely accord with the circular giant chambers; while as a natural consequence of their increased length, they contain a greater quantity of human remains. Meantime the manner in which the deceased were interred deserves peculiar attention, because by such means no unimportant light is thrown on the funeral customs which prevailed at the period. Thus along the sides of the stones forming the walls are found the bones of a number of bodies, which certainly cannot have been placed in the usual recumbent posture, for the space would not admit of it. On the contrary, the position of the remains seems to indicate that the bodies were placed in a compressed or sitting posture; by which means, the advantage of depositing many of them in a small space was obtained[7]. This is peculiarly evident in the single giants' chambers, which were divided into small quadrangular spaces, one for each separate corpse.

In all probability the bodies were placed in the same manner in the circular giants' chambers and in the cromlechs; for the dimensions of the chambers are often so limited that a man of the usual height could not be laid at full length in them.

Of the heaped-up giants' chambers several have been preserved in an uninjured state. Thus in North Seeland the Ullershöi at Smidstrup, in the domain of Fredriksborg, with two chambers; the Julianahöi at Jagersprüs, the well-known giants' chambers at Oppesundbye, Udleire and Oehm in the neighbourhood of Roeskilde; again at Möen; the Röd- dingehöi with two giants' chambers; in Jutland in the domain of Thisted near Ullerup, in the parish of Heltborg, in the so-termed Lundhill an oval giants' chamber, (twenty-four feet long, about five feet and a half broad, and four feet and a half high,) inside of which is a smaller round chamber (six feet in diameter and three feet and a half high.)

This grave is not only remarkable for its peculiar form, but also from the circumstance that the two stones a and b, which stand on each side of the threshold c, contain on the flat surface several markings very faintly carved or rubbed in, which by some are regarded as a species of Runic inscription. These chambers were first discovered in 1837, but as nothing was discovered in the oval and largest of them, it is highly probable that the barrow had been opened and examined at an earlier period, from which the origin of the above-mentioned markings may perhaps be dated. It must not be overlooked in this respect, that in Seeland, at Herresup, in the Odsherred, there has been discovered, in a barrow, a chamber, on the roof of which some figures very faintly carved have also been traced. As some of these are similar to markings on stones in Sweden and Norway, which certainly are to be ascribed to the later periods of paganism, and which are also only found on the outside of the roofing stones, we can only suppose that they date from a later period than that in which the stone chamber (which, as usual, contained only implements of stone) was originally constructed. This however is a circumstance which at present can scarcely be determined with sufficient certainty, and will be better left to future and closer investigation.

An examination of the most remarkable and striking cromlechs and giants' chambers, cannot fail to excite our surprise that the aboriginal inhabitants of Denmark were able to erect such stupendous monuments. How the large cap-stones were brought to lie on the supporting stones is indeed not quite incomprehensible. It might have been effected by forming steep paths or inclined planes composed of earth and stems of trees, from the upper part of the supporting stones to the surface of the surrounding field, and by forcing the stones up these paths by means of levers. It may also be added that possibly the inhabitants had been able to tame and employ the horse, which must have existed in the country from the earliest period. It is still more remarkable if, being destitute of tools of metal, they were in a situation so to split the large roofing and supporting masses of stone, that they are completely flat on the side which is turned towards the chamber. For it is highly probable that many or most of them have been artificially split. Their number is too great to allow of the supposition that they all possess the natural form, whilst it is quite evident that the small flat fragments which fill up the interstices between the supporting stones have been split by artificial means. Hence it is possible that the aborigines were acquainted with the simple method of splitting large blocks of granite, which is still practised in several countries. Holes bored in a certain direction along the veins of the stone are filled with water. Wedges are then introduced into these holes, and struck with heavy mallets till the rock is split into two flat pieces. It must of course be supposed in this case that the aborigines knew how, by means of other stones, to form these holes or perforations in the granite, but this supposition is by no means incredible. Under all circumstances, this much is certain, that the cromlechs and giants' chambers must have been works of enormous labour; they therefore afford a striking proof, that the earliest inhabitants of Denmark could scarcely have led a mere nomadic life, but must have had settled habitations, and that they were a vigorous people who cherished care and reverence for the departed; a trait which is the more admirable, since they were in other respects rude, and destitute of any thing like regular civilization.

II. Tombs of the Bronze-period.

The barrows, cromlechs, and giants' graves of the stone-period, and the barrows of the bronze-period, are totally different from each other. The tombs of the stone-period are peculiarly distinguished by their important circles of stones and large stone chambers, in which are found the remains of unburnt bodies, together with objects of stone and amber. Those of the bronze-period, on the other hand, have no circles of massive stones, no stone chambers, in general no large stones on the bottom, with the exception of stone cists placed together, which however are easily to be distinguished from the stone chambers; they consist, as a general rule, of mere earth, with heaps of small stones, and always present themselves to the eye as mounds of earth which, in a few very rare instances are surrounded by a small circle of stones, and contain relics of bodies which have been burned and placed in vessels of clay with objects of metal.

From the fact that bodies during the bronze-period were burned, it may be conceived that the bronze-period is later than the stone-period, in which it was the general custom to bury the dead without burning. This latter method of interment is peculiar to uncultivated nations, and is unquestionably the most simple and the most natural; the custom of burning the dead supposes a certain developement of religious feeling which is only to be found among such nations as have acquired some degree of civilization. It was a totally different matter however, when towards the close of paganism in the North, cultivation having attained a higher grade, men once more adopted the custom of interring their dead without first burning them. This fact by no means invalidates the assertion, that the mode of interment of the stone-period is the most ancient. That the stone-period extends farthest into antiquity, the tombs which belong to it afford the most unquestionable proofs. At the summit and on the sides of a barrow are often found vessels of clay with burnt bones and articles of bronze, while at the base of the hill we meet with the ancient cromlechs or giants' chambers, with unburnt bodies and objects of stone. From this it is obvious that at a later time, possibly centuries after, poorer persons who had not the means to construct barrows, used the ancient tombs of the stone-period, which they could do with the more security, since a barrow which is piled above a giant's chamber had exactly the same appearance as a barrow of the bronze-period. To prevent misunderstanding it must here be observed, that many persons are of opinion, from the appearance of the barrows when opened, that the different modes of interment of the periods of stone and bronze, the placing bodies in cromlechs and the burning them, prevailed universally at one and the same time. This opinion has however been founded in most cases on very loose grounds, since sufficient attention has not been paid to distinguishing the different modes of interment at the base and the summit of the barrows; for the fact that two kinds of interment occur in the same barrow, by no means proves that such interments belong to the same era. The circumstance moreover that together with unburnt bodies vessels of clay have also been found, in the cromlechs and giants' chambers, has given rise to error. These vessels contain, as we have seen, merely loose earth; but formerly it was constantly as erroneously conceived, that all vessels of clay found in barrows were urns for ashes, and had been filled with burnt human bones. We are certainly not justified in positively denying, that burnt human bones have ever been found in a legitimate grave of the stone-period, but experience has hitherto shewn us that between the tombs of the stone-period and those of the bronze-period, there exists a difference as great, and in fact greater, than that which prevails between the antiquities of the two periods.

The usual mode of interment in the bronze-period appears to have been as follows. A large pile of wood was erected, on which the body was placed. When the pile was consumed, the small bones which remained were collected together with some portion of the surrounding ashes, and placed in an earthen vessel, which was deposited in the midst of the consumed pile and surrounded with stones. In this vessel, in addition to the bones and the ashes, were deposited different small articles of bronze, such as pins, knives, pincers, &c., and together with these the various weapons and ornaments possessed by the deceased. After this the vessel was carefully closed with its usual cover, or, more generally, with a flat stone; the whole was then covered with small stones, which were usually placed in a conical heap, over which the usual barrow of earth was erected. Instead of urns for ashes, very small stone cists about a foot long, formed of four stones placed together, and covered with a fifth, were occasionally used. It is generally speaking characteristic of this period, that the remains of burnt bodies were placed in no definite way and in no definite parts of the hill. In the midst of the consumed pile, the sword and the ornaments of the deceased were occasionally placed, covered with a heap of stones thrown over them, while the urn with the ashes was deposited in the earth which was placed upon them. On the floor of some of these barrows the weapons are preserved in small oval cists of stone, and again in others nothing is found but single portions of bone, while the m-ns with ashes are placed outside. On the very margin of the hill bronze swords and other weapons, as well as ornaments, arc met with, among loose burnt bones, which are not collected in urns, but merely surrounded with small stones. Most of the barrows of this period were family-barrows, serving as places of interment for single families. Hence not only may the floor of a barrow be furnished with a great number of urns, or small stone cists filled with bones, but it is also very common, particularly on the east and south sides, and scarcely a foot in depth below the turf, to find numerous urns surrounded with stones which unquestionably have been deposited from time to time. The number of them, often from thirty to seventy, probably results from the circumstance of many poor persons having by degrees deposited their urns in the barrows of the rich. Since cinerary urns are not unfrequently dug up both in open fields and in beds of peat, the poorer classes have probably been obliged to select this simple mode of interment because they had no opportunity of placing the ashes of their relatives in a barrow.

A remarkable barrow with peculiar contents was examined in 1827, at the village of Vollerslev, in the neighbourhood of Aabenraa (Apenrade). On the removal of the earth, on the south side of the barrow, there was found, above the surface of the surrounding field, a small cinerary urn of clay, and below this a heap of small stones, thrown together. On the removal of these, a very thick stem of an oak, about ten feet in length and split in two, was discovered, which was roughhewn and bore the marks of a saw. The upper part was found to be the cover of a cist hollowed out in the oak stem, six feet long, and nearly two broad[8]. In it was found a mantle composed of several layers of coarse woollen stuff, sewn together, and also some locks of brown human hair, a sword with a handle, and a dagger of bronze, a paalstab as they are termed, a brooch, also of bronze, a horn comb, and a small round wooden vessel with two handles at the sides, in which was found something which had the appearance of ashes.

In the description of this discovery, which is quite peculiar of its kind in this country, it is not mentioned that any remains of an unburnt corpse were observed, which appears singular, because the stem was so far hollowed out that the corpse of a grown man could be placed in it. It is however possible, that in the construction of this barrow, a rule, of which we have already given some examples, has been followed, namely, that the weapons and trinkets have been placed in the most distinguished part of the barrow, while the vessel of clay, which contained the remains of the burnt corpse, was merely placed in the heaped up earth.

The barrows of this period were placed, wherever it was possible, on heights which commanded an extensive prospect over the surrounding country, and from which in particular the sea could be distinguished. The principal object of this appears to have been to bestow on the mighty dead a tomb so remarkable that it might constantly recall his memory to those living near, while probably the fondness for reposing after death in high and open places, may have been founded more deeply in the character of the people. Such a desire would seem of necessity to be called forth by a sea-faring life, which developes a high degree of openness of character, since the man who has constantly been tossed upon the sea and has struggled with its dangers, would naturally cherish a dislike to be buried in a corner of some shut up spot, where the wind could scarcely ever sweep over his grave. For this reason there are traces that the upper surface of several considerable heights, for instance Boobierg in Jutland, and Skamlingsbanken in Sleswig, were used as burial-places by those who were too poor to construct barrows of their own. The cinerary urns here are merely placed about a couple of feet deep in the earth, and without any other protection than a circle of small stones.

The barrows of the bronze-period occur in much greater numbers and extent, both in the islands, and in Jutland, Sleswig, and Holstein. Where the greatest number are found, the population was probably most numerous. Yet the multitude of barrows in single spots induces the idea of battles, after which the fallen were interred on the field. These barrows are met with both in the districts on the coast, which were those first inhabited, as well as in the interior of the country, which at a later period was gradually cleared of wood. It follows thence that they are not to be referred to any very brief period, but rather belong to a long series of years, in which various, and now unknown events, may have occasioned the immigration of allied races of people. As they also date from a period in which, particularly towards the close of it, a connection with other countries, and by this means the opportunity of learning and adopting their manners and customs, was opened, which could not of course be the case during the stone-period, it will as little surprise us that they occasionally differ in structure and arrangement, as that, without exception, they contain corpses unconsumed by fire. These are found in small narrow cists of stone, which are composed of thin flat squares of stone, covered with similar ones; but this mode of interment scarcely came into use till towards the close of the bronze-period. Many of these tombs have also been constructed after the more recent civilization, characteristic of the age of iron, had begun to produce its effect on the people; and from this we can easily perceive that the ancient usages were no longer so closely observed.

III. Tombs of the Iron-period.

We may regard as a result of the circumstance that the iron-period can have commenced only at a comparatively recent date in Denmark, the fact that there exist but very few tombs which can with certainty be referred to it, while of those of the bronze-period there exists a very considerable number. Notwithstanding the circumstance that from this cause our knowledge of the Danish tombs of this period is extremely imperfect, it is still very evident, that between the tombs of the iron, and those of the bronze-period, some difference exists, although that difference is not so marked as that between the tombs of the stone and of the bronze-period. The external form and in some measure the internal structure of the tombs are in particular very similar, while they differ most with regard to the mode of interment, the tombs of the stone-period usually containing unburnt corpses, while those in the barrows of the bronze-period have, generally speaking, been burnt. It is true it was the custom in Sweden and Norway, in the iron-period, to consume the remains of the dead by fire, but of such a practice we find no vestiges, or at least very faint ones, in the tombs of Denmark belonging to the same period.

With reference to the mode of interment which prevailed in the North during the heathen period, the celebrated Icelandic historian Snorro Sturlesen, who wrote a chronicle of the Norwegian kings six hundred years ago[9], remarks that it was at first customary to burn the dead, and this period was termed the age of burning; but at a later period, after the interment of Frej, at Upsala, without the burning of the corpse, many chiefs buried their relatives in barrows, and hence the age of interment took its origin. In Denmark Dan Mikillati (the Splendid or the Proud) was the first who was buried without being burnt. He caused a large barrow to be constructed, and ordered that when he was dead he should be brought and interred there, in his royal pomp and armour, together with his horse and saddle and various other objects. With this occurrence the age of interment commenced in Denmark, yet the age of burning lasted long after among the Swedes and Norwegians. In Denmark therefore the age of burning corresponds with that of bronze, and the age of interment with that of iron. It must however be remembered, that tradition often refers a remarkable change in certain previously existing customs, to certain prominent personages, and so in this case the change in the mode of interment is ascribed in Sweden to Frej, and in Denmark to Dan. The historical foundation for the interment of Dan Mikillatti may probably be that in the age of interment the mode of burial may have been far more splendid and costly than in the so styled age of burning, of which fact the barrows themselves afford very remarkable proofs.

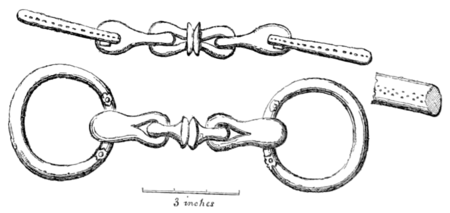

The greater part of the few barrows of the iron-period, which have hitherto been examined in Denmark, are distinguished by the circumstance that they contain not only the remains of the warrior, but also those of his horse[10]. Thus in a barrow near Hersom, in the Rindsharde, domain of Viborg, the skeleton of a man together with that of his horse, and with these an iron sword, a spear, a stirrup, a bridle with a chain bit, and a cross bar at the ends, were discovered. In the same manner in a barrow near Hadberg, in the Galtenharde, domain of Randers, portions of the skeleton of a man and a horse were observed; near them lay an iron axe, a pair of stirrups, and a bridle. In a very large tumulus on the field of Möllemosegaard, in the Sallingherred, domain of Svendborg, were found some years ago the skeletons of a man and a horse, and near them a number of iron objects, among which was a bridle which has been covered with thin plates of silver. In addition to this the barrow also contained several remarkable ornaments for harness, and a large metal vessel[11]. The Sagas mention the circumstance, that the northern Vikings of ancient times were often buried in their ships, over which a barrow was erected; such a mode of interment however, as far as we are aware, has never yet been discovered in any Danish barrow, although it is not improbable that traces of it might be found. It is perfectly natural that the Viking should cherish the wish that his bones should repose in the ship which was his most valuable possession, and which had borne him to foreign lands, to booty and to fame.

In consequence of the increase of the wealth of the North, which was the result of the expeditions of the Vikings, the barrows were constructed on a larger scale than formerly. Among the most remarkable and most costly of the tombs of the iron-period, are those barrows which have sepulchral chambers of wood; one barrow in particular of this kind has been preserved, which, from its peculiar arrangement and the historical recollections associated with it, has no equal in the North. King Gorm the Old, who at the end of the ninth or the beginning of the tenth century, first united the numerous small kingdoms of Denmark into one connected whole, married Thyre the daughter of a petty king of Jutland or Holstein, This queen, who is celebrated in legend and in song, distinguished herself even in early youth by a love for her country, and an ability and integrity, which secured her a lasting memorial in the hearts of the Danes. It is narrated that Gorm while he was wooing her had dreams, which Thyre interpreted, and by this means averted a dreadful famine from Denmark. Out of gratitude the Danes named her Danebod, or the "Ornament of Denmark," a name which she well deserved, since she subsequently erected in Sleswig the celebrated wall or Danewall, (Danevirke,) which served to protect Denmark against hostile incursions.

On her decease, Thyre Danebod was interred after the old northern custom in a vast barrow, which is still to be seen at Jellinge, in Jütland, close to the north side of the church. On the barrow a reservoir was gradually formed, to which miraculous powers were attributed, and in the course of years the sick and the lame made pilgrimages to the spot. On the water becoming dry, it was desirable to cleanse out the funnel-shaped cavity which formed the reservoir, and thus an opportunity was given for examining the tumulus. The searchers first came to a number of small stones, and next to a remarkable burial chamber formed of wood. It was about twenty-two feet long, four and a half high, and covered with beams of oak. The walls, which had been covered with woollen cloth, were formed of oak planks, behind which was a bed of clay firmly trodden down, on which the beams of the ceiling rested. The flooring consisted of oak boards, which were very carefully placed close to each other without being actually joined together. The ceiling had also been provided with oak planks. In this, which was doubtless at that time regarded as a very splendid mausoleum, no remains of bones were discovered, but a chest was found in the form of a round coffer, which was almost consumed by decay. Near it lay the figure of a bird, formed of thin plates of gold, and the silver cup already described, (page 72,) which was covered inside with a thin plating of gold. Besides this were found merely another figure of a bird, and some other trifles of less importance, such as the remains of metal plating, painted pieces of wood, &c. The contents of this remarkable barrow were comparatively unimportant, but it had been opened before. It was plainly discernible that four of the beams of the ceiling had been cut through at some previous time, and that an entrance to the tomb must have been effected in this way, probably by the well-known openers of barrows in the middle ages. The discovery of a short wax candle, placed on one of the beams of the ceiling which had been cut through, still more confirms this supposition.

Opposite to the barrow of Thyre, on the other side of the church at Jelling, is seen a similar elevation, in which her consort King Gorm is interred, which however has not yet been examined. These tumuli are the largest and most considerable in the whole country, their height is about seventy-five feet, and their circumference at the base above five hundred and fifty feet. Such mounds are extremely rare in the North. Usually, the barrows are only from twelve to twenty-two feet, the latter size being very uncommon.

It is worthy of notice that at the same period, when large elevations were thus piled over deceased persons of distinction, bodies of wealthy persons were deposited in the natural sandbanks. In several places in this country, for instance in the parish of Herfölge, at Himlingöie, in the domain of Vallö, at Sanderumgaard, and at Aarslev in Fühnen, there have been discovered in sand-banks where no artificial barrows were perceptible, unburnt bodies, trinkets of gold and glass, together with a buckle with a Runic inscription, mosaic birds, in short, objects which with reference both to the shape and the material, are undoubtedly to be referred to the latest period of paganism. The circumstance that several corpses are here usually found interred, leads to the conjecture that towards the close of the heathen period there were general places of interment, which form the transition to the custom which became prevalent in the Christian era of interring the dead in church-yards[12].

IV. Tombs in other countries,

(particularly in Sweden and Norway.)

In order that the Danish memorials may appear in their true light and connection, it will be of importance to enquire in what regions of other countries similar monuments of antiquity have been observed. Without such a general examination it would scarcely be possible to derive satisfactory historical conclusions from the enquiry.

We first turn then towards the South. Stone chambers, or cromlechs, or low barrows, encircled with stones, which completely accord with the cromlechs of our stone-period, occur in Pomerania, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg, Hanover, in fact in the whole of the north of Germany, in England, Ireland, Holland, (particularly in the northern part,) and in the west and south of France. Their contents are everywhere the same. Where they have not previously been opened there occur skeletons with objects of stone and amber; or one meets with stone implements and fragments of vessels of clay, just as in Denmark. Thus in France cromlechs of the stone-period, which contained skeletons and implements of flint, have been found, not only on the western coast, but also singly in the middle of the country, even in the southern part itself, in the neighbourhood of the Pyrenees and of Marseilles. They occur also in Portugal and in Spain, while, as far as is known, they never have been discovered in the interior parts of Europe, in the south of Germany, Italy, Austria, or the east of Europe. They are very distinct from the tombs of the pagan era of those countries, both in their structure and their simple funereal contents.

The limits of the tumuli or barrows of the bronze-period cannot be so well defined, since these, as regards their form and general arrangement, have much similarity with most of the tumuli of Germany and other European countries of that period, in which the practice of burning the dead generally prevailed. Barrows which contain bronze objects with spiral ornaments, like ours in Denmark, do not occur farther south than in Mecklenburg, and possibly in Hanover; and on the contrary, barrows, with bronze articles of somewhat different character, occur in most countries of the south and west of Europe, both on the coasts and in the interior parts.

The barrows in the three northern kingdoms differ very much from each other. The cromlechs and giants' chambers of the stone-period, which occur generally in Denmark, meet us only in the south-western part of the present Sweden, particularly in the old Danish country of Skaane in West Gothland, in Holland, and Bahuslehn; but they are not found at all in the north-east and north of Sweden, nor in the whole of Norway. The barrows, cairns, and stone circles of those districts have a totally different character; the large and peculiar cromlechs disappear both from the exterior and interior of the barrows. Above all, however, it is to be observed, that the bodies have not been deposited unburnt, except at a much later period; in the more ancient, burnt remains are always met with. Although this mode of interment was prevalent in Denmark during the age of bronze, yet the barrows in Norway and Sweden which lie north and east of the limits of the cromlechs of the stone-period, have scarcely any resemblance to the barrows of Denmark of the age of bronze; for these have about the same limited extent in the peninsula of Scandinavia, as the cromlechs and giants' chambers of the stone- period. A short description of the monuments of Sweden and Norway will illustrate the difference of the graves in the three kingdoms of the North.

As soon as we penetrate from the completely Danish districts of the south-west of Sweden, with, a new aspect of nature, new memorials of antiquity also meet us. Instead of wide, extended, and fertile plains, we see only rocks, which are either altogether unproductive, or grown over with scanty trees, and with them innumerable masses of stones which have rolled down. This abundance of stone, and consequent deficiency of loose earth, cannot have been without its effect on the external arrangement of the barrows. Barrows composed of mounds of earth are henceforth considerably lower than in Denmark, while those which chiefly consist of stone are the most prevalent. An object almost unknown among us is the cairn (steenrör), as it is called, which frequently lies on the highest rocks, and by which are indicated barrows which are destitute of any covering of earth, and are composed of a heap of stones piled together, on the floor of which an oval stone cist is usually found. They are occasionally of very considerable size, for instance more than twenty feet in height and fifty paces in diameter. The other barrows, which are somewhat more numerous, and are partly mixed with earth, are considerably smaller, since they are constructed of very small stones heaped together, and hence they but seldom rise more than from three to five feet above the surrounding surface. Great variety is observable in their form. Usually they are either circular or oval, and enclosed by a circle of stones, in which the single stones are close to each other; occasionally they are quadrangular, and often with a larger stone at each corner; and again they occur of a triangular shape. The last mentioned, which in general have sides much bent inwards, are often adorned with an erect and somewhat lofty stone in the centre, where the grave itself is placed, and with a similar one at each of the three ends. Yet there are also circular and quadrangular enclosures of stone which do not surround heaps of stone mixed with earth, but merely a level surface. These have been named places of justice, (Tingsteder,) or of sacrifice and worship, (Offersteder,) or of contest, (Kampkredse.) That they also, at least in general, are graves, is evident from the circumstance that they are met with in great numbers, and contain urns of clay, with burnt bones, ashes, and other antiquities. The most remarkable places of interment in Sweden are un- questionably the ship barrows (Skibssœtninger), as they are named. By this term is understood an oblong enclosure of stones running to a point at the ends, which is filled with a heap of small stones mixed with earth, while occasionally the space enclosed is quite level. At each end is usually seen an upright stone, by which doubtless the stem and stern of a ship are indicated. The resemblance to a ship is still more obvious from the circumstance that there exist similar enclosures of stone, with a tall stone in the middle, in imitation of a mast, and with several rows of small stones which go across the enclosure, and represent banks of oars. They lie chiefly in the neighbourhood of the sea, for instance in Gothland and Oeland, but in particular in Bleking, where they are met with in several places in considerable numbers, associated with round, square, and triangular graves; at the place called Listerby Aas alone are seen about a hundred, although many have perished in the course of time. They differ considerably as to size, occurring from eight to sixty paces long, and two to fifteen paces broad: in the larger ones the terminal stones are from twelve to sixteen feet in length. In general they are to be considered as burial-places of the Vikings[13]; in single instances they may have been erected m memory of some engagement at sea.The tall narrow standmg stones termed "Bautastene," or memorial stones, were unquestionably, as the name indicates, memorials; they are usually from nine to twenty feet long, and stand in the middle or at the side of the barrow. At Stenehede in Bahuslehn are seen nine entire bauta-stones, and three which have been split in two, in a row fifty paces long, between oval and round barrows. But still more remarkable is the field of battle situated not far from the above at Gresby, in the parish of Tamune, where, in a short space, about a hundred and thirty very low barrows, partly round, partly oval, and surrounded with stones, occur, of which about fifty appear to have been adorned with standing stones, from seven to fifteen feet in length. There are about forty of these stones remaining, but only sixteen stand erect[14].

With the exception of the extensive king's barrows near the church at Old Upsala in Sweden, which in size may be compared to the barrows of Gorm and Thyre, at Jelling, in Denmark, and thus may justly be reckoned among the most remarkable monuments of the North, which are formed of earth, the barrows of Sweden, as has already been mentioned, are strikingly low. Hence they include only in single instances any large structures of stone or wood. In this particular they differ from the barrows of Norway, which, if they consist of earth, are, taken as a whole, more extensive, both as regards their internal and external arrangements. They not unfrequently cover several wooden structures, in which many and valuable antiquities are placed. This is particularly the case with the Norwegian cairns. In general, however, the resemblance between the tombs of Norway and Sweden is very obvious. The same low round quadrangles, triangles, and ship-like barrows, surrounded with stones, as well as the standing stones, are found in these two neighbouring kingdoms. Among the monuments of antiquity were formerly reckoned a peculiar kind of large stones, which are so placed on the edges of rocks that they may be made to shake merely by the strength of the arm, without losing their equilibrium; hence they are usually called Rocking-stones, (Rokkestene.) Several such have been discovered at Bornholm, and in great abundance in Norway and some parts of Sweden. They were formerly considered to have been heathen altars or oracles. It is now, however, believed that they are merely rolled stones, which, from various natural causes, have been loosened from the rocks, and have acquired such a position that they can be shaken without falling down.

The barrows of Sweden and Norway have not only a peculiar external form, but as regards their contents they are essentially different from the Danish barrows. The latter usually contain antiquities of the stone and bronze period, which is never the case with those of Sweden and Norway, since they, almost without exception, contain antiquities of the iron-period, such as weapons and implements of iron, shell- shaped brooches with open-work, interlacing ornaments and filigree-work, and beads of glass and mosaic. Besides, the corpses placed in them are burnt, while those of the Danish graves of the iron-period are almost always interred in an un- burnt state. Traces of such a mode of interment in barrows occur but rarely in the Norwegian barrows, and more rarely still in those of Sweden, and then they are always of the period of the transition from paganism to Christianity. By this circumstance the statement of Suorro is confirmed, that the age of burning lasted longer in Sweden and Norway than in Denmark. There is another fact which must not be overlooked, that in Denmark the age of burning corresponds with the age of bronze, but in Sweden and Norway with that of iron.

On account of the agreement in date, it must be mentioned that graves are seen in Iceland, (which country was first peopled by immigrating Norwegians at the end of the ninth century,) which completely resemble the places of interment common in Norway and Sweden, which are low and enclosed with stones, and which lie in many districts associated with ship- like barrows, and with triangular and quadrangular enclosures of stone. From the foregoing enquiries it will be perceived that similar enclosures of stone and low barrows of earth, together with the long and narrow stones erected over them, are scarcely to be observed in Denmark. It is true there is a report that in the domain of Apenrade, in the neighbourhood of the sea, several of these ship-like enclosures, the Dannebrog ships, (Dannebrogskibene,) as they were called, have been found. There are likewise some stone enclosures at Hiarnoe, which appear to bear some resemblance to these ship-formed enclosures, but they are unique of their kind, and as their origin moreover is very doubtful, they naturally cannot be considered to outweigh the obviously according testimony of all other barrows. The result of the comparison between the monuments of Denmark and those of the rest of the North is therefore as follows. In Denmark and the south-west portion of the present Sweden there are numerous cromlechs of the stone-period and barrows of the bronze-period, and but a few tombs from that of iron, and those only from the most recent period. On the other hand, in the rest of Sweden and in Norway there are neither cromlechs from the stone-period nor barrows of the bronze-period, but in their stead a number of peculiar barrows and stone enclosures, which are different from those of Denmark, and which belong both to the earliest and latest period of the age of iron[15].

The tumuli, therefore, fully accord with the antiquities, since they shew that the stone and bronze periods do not apply to Norway and Sweden as they do to the ancient Danish districts, and that the later period of the iron age comprises all three kingdoms; that Norway and Sweden, however, were immediately its home, whence it perhaps extended itself at a later period over Denmark. This fact clearly indicates that in very ancient times Denmark was more fully peopled than the other nations of the North.

It is worth observing, that the same mode of interment which prevailed in Denmark in the later part of the iron- period, viz., that of burying the dead unburnt in large burying places, without raising tumuli or barrows over the graves, also prevailed both in the north and south of Germany, in Mecklenburg, Bavaria, Baden, in Switzerland, Alsace, France, and in England. In all those countries this mode of interment undoubtedly was used immediately before the introduction of Christianity. In some of these burying places there have been found Christian crosses or ornaments, and also Christian inscriptions.

Since we are thus enabled by a knowledge of the arrangement, the age and the relations of which the barrows of Denmark bear to the memorials of other countries, to distinguish the tombs of different ages, we are by this means enabled to correct many an erroneous tradition which has, from time to time, crept into history. Some explanatory instances of this sort may not be wholly without interest.

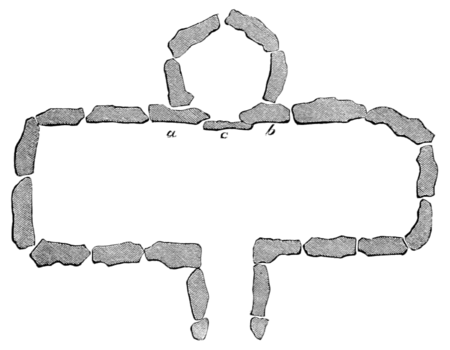

In the battle, so celebrated in early history, which took place at the Braawalla-heide in Sweden, between the Danish king, Harald Hildeland, and the Swedish king, Sigurd Ring, Harald Hildeland fell in the conflict. His corpse, so the ancient records relate, was placed on a funeral pile and burned, and his ashes brought to a tumulus raised at Leire, which tradition still points out. It is somewhat injured, but consisted in ancient times of an oblong elevation of earth, of about seventy to eighty feet in length, and twenty-four feet in breadth; on each of the long sides stood ten erect stones, the four corner stones being somewhat larger than the rest. On the north side, was a small barrow of earth, at the foot of which was the grave itself. This was formed of three large and two small stones placed in a quadrangle; the square between was filled with small flat stones. On the large stones once rested a large roofing stone, which was destroyed a hundred years ago. The whole appearance of the tomb will be rendered more plain from the accompanying illustration.

From this figure it will be evident, beyond all doubt, that this is merely a common cromlech of the stone-period; in fact, wedges of flint have been found in the earth, which has been excavated from the chamber; and thus it is obviously impossible that it can have been erected to Harald Hildeland, who, according to the narratives of the ancient Sagas, must have lived at a much later period. We might cite a number of similar unfounded tales of tombs, in which certain wellknown kings, for instance Humble and Hjarne, are said to have been interred; but we will point out only the most remarkable and celebrated of the whole, namely, that of King Frode Fredegode, (or the Lover of Peace,) whose corpse was borne for three years about the country before it was buried. It was finally interred in the long extensive barrow at Værebro Mölle, in the neighbourhood of Frederickssund in Seeland. The tradition is of such antiquity that the celebrated historian Saxo Grammaticus, six hundred years ago, recorded it from an ancient ballad. Frode's barrow, as it is called, is a long elevation, which appears to have been formed by human hands, and at a distant period was surrounded with large stones, several of which were remaining a few years ago. At one end of the barrow is a semicircular cavity, from which extends a depression of the soil to the side of the hill. In this hollow lie several large stones, the remains of the destroyed funereal chambers. About a hundred years ago, Bishop Rönnor caused the chambers to be examined, but nothing was found in them, except a heap of human bones, such as usually occur in graves of the stone-period, among which this Frode's barrow must be included. If Frode Fredegode is to be regarded as an historical personage, it is probable that he may be interred at Værebro, but one cannot help doubting whether he reposes in the tomb to which tradition has assigned his name, for in his time bodies were certainly no longer placed in cromlechs. On the whole the country near Værebro and Leire is particularly rich in cromlechs of the stone-period, and no doubt for this reason, that those districts which were favourable for hunting and fishing had considerable attractions for the aboriginal inhabitants. That "the great place of sacrifice" of the kings of Leire, near Snoldeler, in the parish of Vor Frue, (Our Lady,) at Roeskilde, which consists of a barrow surrounded with stones, with three chambers, is also nothing more than a cromlech of the stone-period, may safely be assumed from what has been already stated.

The importance of critical illustrations of this nature, acquired by means of barrows, is not confined to the circumstance that certain unfounded traditions, which have partly been collected in later times, are by this means destroyed and banished from history. We learn beside, which is of equal importance, that such traditions can only be received with the greatest caution, even when they relate to particular spots and barrows, and when the reference dates some hundred years back, unless peculiar circumstances confirm the date and authority.

V. Runic Stones.

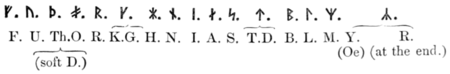

Antiquarian remains and barrows would convey much more trustworthy information of the past if they were in all cases furnished with inscriptions. From the languages in which such inscriptions were composed, we should then be able to form conclusions as to the descent and connection of the earliest inhabitants of the North; since, it is sufficiently clear that men who belong to the same stock, speak languages which are, at all events, allied to each other. But unfortunately inscriptions of ancient date are extremely rare. In the stone-period, writing, with the exception perhaps of single hieroglyphic signs and representations, appears to have been completely unknown. Of the bronze-period no distinct traces of inscriptions appear to have been discovered; and it is only in that of iron, that inscriptions occur which are inscribed in the so termed Runes, or Runic letters. The usual alphabet, which consists of sixteen characters, is as follows:

There are, however, deviations from the above, and several varieties of the characters themselves ; beside which there are other various kinds of foreign Runes still more different, such for instance as the Anglo-Saxon. Inscriptions of this kind, probably on account of some unknown peculiarities in their arrangement, are, generally speaking, very difficult to interpret.

In ancient times the Runes were scratched on metal, as in the case of trinkets and ornaments, or were carved on wood, particularly on staves of wood and on bark, or were engraved on stone. As wood, bark, and in some degree metal, are in the course of time consumed in the earth, those inscriptions are best preserved which are met with on the large stones, which, from the Runes, are called Runic stones.

These are usually tomb-stones, which have been erected over the graves of deceased persons of distinction. The Runic stones belong partly to the pagan, and partly to the early Christian period. As an unquestionably pagan Runic stone may be mentioned that at Glavendorp in Fuhnen, discovered at the beginning of the present century. The inscription which is divided into three parts is inscribed on its three sides, and maybe rendered into English, as follows: 1. "Raynhilde placed this stone to Ale Solvegolde, a man well deserving of honour." 2. "The sons of Ale erected this barrow to their father, and his wife to her husband, but Sote inscribed these Runes to his lord. May Thor bless these Runes." 3. "Accursed be he who moves this stone, or takes it to another place." It is deserving of particular attention, that Thor, their deity, is here particularly appealed to. In general the inscription on the stone merely records by whom, and for whom, it was erected, with the addition of various circumstances. These inscriptions are therefore generally uniform, yet they afford valuable and interesting details for history, particularly with reference to domestic relations. They seldom refer to foreign, great, or important events.

Among the most remarkable stones in Denmark, in this respect, are the two monumental stones at Jellinge, over Thyre Danebod, and Gorm, and the stone at Söndervissing. Of the Jellinge stones, which are both to be seen before the church door, the smallest was erected by Gorm to Thyre. It is of granite, five feet high, and three feet broad, and somewhat flat. On the two broad sides is the inscription.

That on the front is, according to the characters, "Gumer kunugr garði kubl ðosi aft ðurvi runu;" and that on the back, "sina Danmarkarbut." "King Gorm constructed this barrow to his wife Thyre Danmarksbod." That Gorm is here mentioned as having erected the barrow to his wife is peculiarly striking, since all authors agree that Thyre survived Gorm. In case, therefore, we do not assume that the barrow was erected and the stone engraved while Thyre was still living, which is by no means without example, or authority, we must, of necessity, conceive that authors have left us very imperfect details of these events, and that Thyre actually died before Gorm.

The large stone at Jellinge was erected to the memory both of Gorm and of Thyre, by their son King Harald Blaatand. It is eleven feet high, and has, on its three sides, an inscription which runs thus: "King Harald caused this barrow to be made to his father Gorm, and his mother Thyre; the same Harald who acquired all Denmark, and Norway, and Christianity as well," (that is, caused his people to be baptized.) On the third side of the stone is inscribed a figure of Christ, which is recognisable by the circumstance that in the nimbus round the head the points of a cross are to be seen. By this emblem our Saviour was always distinguished from the Saints in the early representations. The Runic stone consequently affords, by means of the inscription and the figure of Christ, a valid contemporaneous proof of the introduction of Christianity into Denmark. It is not only a memorial of Gorm and Thyre, but is equally a monument of the triumph of Christianity over paganism; and hence it may justly be styled the most remarkable monument in Denmark, if not, in the whole North.

The Runic stone at Söndevissing, in Tyrstingherred, in the district of Scanderborg, which was only discovered a few years ago, appears to have been erected about the same time as the great stone at Jellinge. The inscription is "Tuva lot görva kubl, Mistivis dotir uft muður sina, kuna Haralds kins guða Gurmssunar." That is, with the addition and explanation of certain words, "Tuva caused this barrow to be constructed; she was a daughter of Mistivi; she made it to her mother, and was the wife of Harald the Good, son of Gorm." By Harald, the son of Gorm, we cannot but suppose that Harald Blaatand is intended; and, if it were confirmed that mention is here actually made of him, this inscription acquaints us with a fact which was hitherto unknown, namely, that his wife was named Tuva. The whole of the history of that period is so defective that we cannot wonder at the name of a queen not being mentioned by historians. The Runic stone further adds that Tuva was a daughter of Mistivi, a statement which, in this case, is of double interest, since we know from other sources that there existed, at that period, a Wendish prince named Mistivi, (possibly the same as the Mistivi of the Runic stone,) who in the year 986 destroyed Hamburgh. Harald must in such case have stood in such relation to the Wends, as in a political point of view, could not be without importance with reference to Denmark.

Although instances are most rare in which Runic stones afford such important historical information, yet viewed collectively they deserve peculiar attention, even those which seem to have very unimportant inscriptions[16]. Since, in fact, inscriptions are the oldest relics of language which we possess, the Runic stones must be considered as the oldest monuments both of the extent, and the construction of the language of antiquity. With reference to the decision of the often contested question as to the diffusion of the Danish language towards the South, in ancient times, it is of no mean importance, that at the south-east end of the ancient wall of Kograven in Sleswig, which lies somewhat south of the Dane wall or Danevirke, and is unquestionably very ancient. Runic stones have been discovered with inscriptions in the ancient Danish tongue. Since it is further known from history that, in ancient times, one language was spoken throughout all Scandinavia, a circumstance which is confirmed by the fact that the inscriptions on the Runic stones in the three northern kingdoms, are written in one and the same language, with merely casual variations caused by peculiar circumstances, it can scarcely be doubted, that a thorough investigation into the collective Runic memorials of the North will afford important assistance towards a knowledge of the Danish tongue in its most ancient form; and thus contribute to its improvement in future times. The number of Runic stones in Denmark is not very considerable; and in order to obtain the desired result from their investigation, it will not only be necessary to keep a watchful eye over the preservation of those already known to exist, but attention must, in like manner, be directed to the discovery of others. There are undoubtedly numerous Runic stones still existing, either buried in the earth, or standing in places where the inscriptions are not seen; at all events, such stones have constantly been discovered from time to time, several of which have been very remarkable. It is peculiarly desirable when blocks of stone are to be split, that care should first be taken to ascertain whether any inscriptions exist on their sides, and should such prove to be the case, the stones ought to be preserved for more complete investigation.

Before any correct idea was formed of the value of Runic stones many remarkable monuments had been entirely destroyed. At the present day, however, when the love of our native tongue strongly prevails, it is to be hoped that the most ancient memorials of the Danish language will not be destroyed from indifference, or for the sake of a trivial gain.

- ↑

The accompanying woodcut exhibits the south view of a small cromlech at L'ancresse in the Island of Guernsey, described in Mr. Lukis' curious paper 'On the Primeval Antiquities of the Channel Islands,' printed in the Third No. of the Archæological Journal, pp. 222—233. Several stone hammers and arrow-points were found in it in the year 1838, as also some portions of earthen vessels, the latter being in several instances of a finer description than that discovered in the large cromlech on the hill near to it.—T.

- ↑

The accompanying woodcut, for which we are indebted to Mr. Lukis' paper already mentioned, represents a round cromlech at Catiroc in the Island of Guernsey, called the Trepid; a name, as Mr. Lukis well remarks, "sufficiently modern, to denote the loss of its original appellation." This cromlech was covered by three or four cap-stones, the principal of which remains in its place, the others have fallen in; and in the interior were found urns, human bones, and flint arrow-heads.—T.

- ↑ The accompanying engraving represents the interior of the cromlech at L'ancresse, in the northern part of Guernsey, explored by that intelligent observer, Mr. Lukis, in 1837, and described by him in the first vol. of the Archæological Journal. From this cromlech about forty urns of different sizes, some being 18 and some not more than 4 inches in height, were obtained; "but," adds Mr. Lukis, "from the quantity of pottery found therein, not fewer than one hundred varieties of vessels must have been deposited from time to time during the primeval period."—T.

- ↑ Remains of a precisely similar character have been found in this country: and the following engraving represents portions of a trough and some stone hammers, quoits, and other implements found in the cromlech at L'ancresse, described by Mr. Lukis, and the next exhibits the position of one of the vases alluded to in the preceding note as having been discovered in the same locality; and the manner in which it was surrounded by animal remains, chiefly bones of the horse, and of the ox, and tusks of the boar.—T.

- ↑ The reader will find much curious illustration of the connection which exists, in the minds of the common people, between the giants of popular mythology and the monuments we are considering, in that storehouse of Folklore, Grimm's Deutsche Mythologie, (ed. 1844,) p. 500, et seq. He will there see how works formerly ascribed to the giants have, since the introduction of Christianity, been attributed to Satanic agency. While on this subject, it may be remarked, that the name of giants' chambers, proposed by Mr.Worsaae, has its counterpart in the name generally bestowed upon cromlechs in the south-east of Ireland, where they are commonly designated giants' graves or beds; while in the north and west they are called beds of Dermot and Graine, Leaba Diarmada agus Graine, from a legend very current through the country of their having been erected by Dermot O' Duibhne, with whom Graine, the wife of Finn Mac Coul, eloped. Finn set out in pursuit of the fugitives, but they escaped for a year and a day, during which time they never slept in the same bed for more than one night. Hence the number of these in Ireland was 366, according to the legend. See Mr. Wakeman's excellent little "Hand-Book of Irish Antiquities, Pagan and Christian," p. 12.—T.

- ↑ The annexed cut, from the Journal of the Archaeological Association, (vol. i. p. 26,) shews the position of the stones, and the form of the cromlech Du Tus, or De Hus, when it was examined in 1837. The outer circle of and the total length of the chamber stones is about sixty feet in diameter, nearly forty feet from east to west.— T.

- ↑ The accompanying engravings, derived from the communications of Mr. Lukis, afford remarkable illustrations of the prevalence of this custom.

The first, from the Archæological Journal, vol. i. p. 146, represents the interior of a cromlech situate on the summit of a gentle hill standing in the plain of L'Ancresse, in the northern parts of Guernsey. The second woodcut, (from the Journal of the Archæological Association, vol. i. p. 27,) which is yet more strikingly corroborative of the accuracy of Mr. Worsaae's statement, exhibits the posture of two skeletons in a vertical kneeling position, discovered in 1844, in the chamber of the cromlech Du Tus, which is marked B in the woodcut already inserted, (vide note u, p. 88.) On the removal of the capstones, the upper part of two human skulls were exposed to view. One was facing the north, and the other the south, but both disposed in a line from east to west. As the examination proceeded downwards into the interior, the bones of the extremities became exposed to view and seen to greater advantage. They were less decomposed than those of the upper part. The teeth and jaws, which were well preserved, denoted that they were the skeletons of adults, and not of old men.—T.

- ↑ A similar wooden coffin formed from the trunk of an oak, split in two for the purpose, both parts being of nearly equal capacity, and still retaining the bark upon them, was found a few years since in a tumulus at Gristhorpe, between Scarborough and Filey, and contained the skeleton of what was supposed to be an ancient Briton. With it were found a brass and flint spear-head and flint arrow-heads, a wicker basket, &c., the particulars of which were published in a pamphlet by Mr. William Williamson in 1834. It appears from a passage in the Earl of Ellesmere's very useful "Guide to Northern Archæology" that this discovery and a similar one at Biolderup form the subject of a paper in the Nordisk Tidskrift for Oldkyndighed.—T.

- ↑ The Heimskringla, or Chronicle of the kings of Norway, of which an English translation in three volumes was published by Mr. Laing in 1844. The antiquarian reader will however be pleased with a German translation by Mohnike, (Stralsund, 1837,) who unfortunately died shortly after the publication of the first volume, His notes and commentaries upon Snorro's work afford most interesting and valuable illustrations of the early history of the North.—T.

- ↑ See on this subject a curious note in the appendix to Mr. Kemble's translation of Beowulf, descriptive of the obsequies of a Teutonic hero.

In an extract from the Fornaldar Sögur, edited by Rafn for the Antiquarian Society of Copenhagen, which relates the particulars of the funeral of Haralldr Hilditavn, is a very characteristic passage descriptive of the slaughter of the horse, and the placing the chariot and saddle in the mound, that the hero may take his choice between riding or driving to Valhalla.—T.

- ↑ In a paper by the Rev. E. W. Stillingfleet, in illustration of some Antiquities discovered in tumuli on the wolds of Yorkshire, published in the York volume of the Archæological Institute, will be found a remarkable account of the discoveries of two distinct skeletons of what Mr. Stillingfleet designates British charioteers, from which the following are extracts.