The Story of the Flute/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII.

FAMOUS FLAUTISTS.

Sec. I.—Foreign players—Quantz—Frederick the Great—Royal flautists—Early French players—Hugot—Berbiguier—Tulou—Drouet—Furstenau—Doppler—Dorus—Demerssemau—Ciardi—Briccialdi—Ribas—Terschak—Altes—Taffanel.

Sec. II.—British players—Early performers—Ashe—Charles Nicholson—Richardson—Clinton—Pratten—B. Wells—Henry Nicholson—Svendsen—Principal living flautists.

SECTION I.—FOREIGN PLAYERS.

A friend once begged Scarlatti to listen to a flute-player. "My son" (replied the composer), "you knowQuantz I detest wind instruments; they are never in tune." He did, however, at length consent to listen, and was forced to confess that he did not think the instrument was capable of playing so well in tune or producing such sweet sounds, and he subsequently composed two solos for the performer in question: Johann Joachim Quantz, the first European flautist of whom we have any full details. Born in Oberscheden, near Gottingen, in Hanover, on the 30th of January 1697, the son of the village blacksmith, young Quantz was for a time apprenticed to that trade. His father disliked music, but both his parents died before the boy reached his tenth year; and Johann—who, though not knowing a single note of music, had already played the bass viol at fairs—went to live with his uncle Justus, the Stadt-Musikus at Merseberg. Here Quantz learned to play the violin, flute, oboe, trumpet, sackbut, cornet, horn, bassoon, viol-de-gamba, clavecin, and a few other instruments! Trusting to his feet, his fiddle, and his flute, he went about 1714 to Dresden, and thence to Warsaw in 1718, where he was appointed oboist in the Polish Chapel Royal, having refused the post of Court trumpeter. Despairing of attaining perfection on the violin, and finding that oboe-playing injured his embouchure for the flute, he abandoned both these instruments, and henceforth devoted himself solely to the flute, studying under Buffardin, the famous French flautist, who was a member of the King of Poland's band. He visited Italy (1724-6), where he met Vivaldi and Porpora. At Naples he was in the habit of playing daily with a certain handsome Marchioness. One day, whilst so engaged, the Spanish Ambassador, who was a lover of the lady, called and stared at Quantz, but said nothing. A few evenings later Quantz was shot at whilst driving to a concert; and instantly arriving at the just conclusion that he had aroused the jealousy of the Spaniard, forthwith quitted Naples, without even bidding the fair lady farewell! He next visited Paris—where he was much pleased with Blavet, the flute-player at the Opera—and London (1727), where Handel and many others endeavoured to persuade him to remain, but after three months he returned to Dresden. In 1728 he began to give lessons in Berlin to the Crown Prince, who played the flute when only eight years old. Quantz is the only flautist, so far as I know, mentioned in any great historical work. Carlyle tells us that Rentzel, the drill-master of the Prince's miniature soldier company, was a fine flute-player, which probably drew little Fritz's attention to the flute. The Queen arranged and paid for the lessons unknown to the King, as the latter considered music effeminate, classing his Court musicians with lacqueys, and forbade his son under severe penalties to play; "Fritz is a Querpfeifer and Poet, not a soldier," he would growl. At these clandestineFrederick

the Great lessons the Prince used to change his tight Frederick uniform for a gorgeous scarlet and gold dressing-gown. On one occasion he was nearly caught by his tyrannical father; there was only just time to hurry Quantz, with his music and flutes, into a closet used for firewood. His Majesty, by Heaven's express mercy, omitted to look into the closet, wherein poor Quantz spent a bad quarter of an hour, trembling in every limb. In 1741 he entered the service of Frederick, and spent the remainder of his life as Court Composer at Potsdam. His salary was £300 a year for life, 100 ducats for every flute he made for the King, and also 25 ducats for each of his flute compositions. He lived on terms of the closest intimacy and friendship with Frederick; they only once had a real quarrel, and even on that occasion the King admitted he was in the wrong. Quantz's decision on musical matters was considered final, no new player or singer being ever engaged without his approval. His duties consisted in daily playing flute duets with the King and writing flute concertos for the evening concerts at the palace of Sans Souci.[1] Burney, who was present at one of these concerts, which began at eight and lasted an hour, thus describes it:—The concert-room contained pianos by Silbermann and a tortoise-shell desk for his Majesty's use, most richly and elegantly inlaid with silver; also books of difficult flute passages—"solfeggi," or preludes: some of these books still exist at Potsdam. Before the concert began Burney could hear Frederick in an adjoining room practising over stiff passages before calling in the band. The programme on the evening in question consisted of three long and difficult concertos for the flute, accompanied by the band. The King (who generally played three, and occasionally five, concertos in a single evening) "played the solo flute parts with great precision, his embouchure was clear and even, his finger brilliant, and his taste pure and simple. I was much pleased and surprised with the neatness of his execution in the allegros, as well as by his expression and feeling in the adagios; in short, his performance surpassed in many particulars anything I had ever heard among dilletanti or even professors. His cadenzas were good, but long and studied. Quantz beat time with his hand at the beginning of each movement, and cried out 'Bravo!' to his royal pupil now and then at the end of solo passages, a privilege permitted to no other member of the band." On one occasion Karl Fasch, the pianist, dared to add a "Bravissimo!" The King stopped playing, and withering poor Fasch with a look, ordered him to depart, and it was only after an explanation to the King that Fasch was a new hand and did not understand etiquette that the sovereign permitted him to return. Sometimes during these concerts the King would sit behind the conductor and follow the score; woe betide any performer who made any mistake. In the morning, on rising from bed, the King often used to walk about his writing-room playing scales and improvising on his flute. He said that while thus employed he was considering all manner of things, and that sometimes the luckiest ideas about business matters occurred to him. He also often played for about half an hour after his early dinner. He allotted four hours daily to music.

Quantz never flattered the King; if he played well, Quantz told him so; if not, Quantz held his tongue, and merely coughed gently. Once he coughed several tunes during the performance of a new concerto by Frederick. When it was over Frederick said to his first violin, "Come, Benda, we must do what we can to cure Quantz's catarrh." Frederick employed a man specially to keep his flute in good order, calling it his "most adorable princess."[2] When he gave up playing, and left his flutes and music packed up at Potsdam, he said to Benda, with a voice quivering with emotion, "My dear Benda, I have lost my best friend!" He was extremely nervous when playing, often trembling violently, and never attempted a new piece without private practice. He did not possess much dexterity in rapid passages, and is said also to have been rather a bad timist. He never played any pieces save his own compositions or those of Quantz, which he would never allow to be printed. The King himself is said to have composed one hundred concertos (one was played at a concert in Dresden in 1912), chiefly after retiring for the night, which he did at 10 p.m. He merely wrote down the melody, with directions as to the other parts—e.g., "Here bass play in quavers"; the score was then completed by his Chapel Master. Late in life the King, having lost his front teeth, and beginning to be a trifle scant of breath, found Quantz's long passages somewhat trying, and he ultimately gave up practising the flute, or even listening to music. Once when a celebrated flautist played before Frederick at Potsdam the monarch only fetched his own flute and played a piece for the artist, who expected a more substantial reward. Voltaire says the King played "as well as the greatest artist," but Bach remarked, "You are mistaken if you think he loves the flute: all he cares for is playing himself." Two of his flutes are in the Royal Museum, Berlin; one silver, the other wood.[3]

The king was fond of triplet passages of this kind—

hence Quantz always introduced them into his concertos, and Kirnberger, the musical critic, said he could recognize Quantz's compositions by the "sugar-loaves." Quantz died of apoplexy at Potsdam on July 1 2th, 1773, and was attended in his last illness by Frederick himself, who erected a handsome sandstone monument there to his old instructor and friend. Contemporaries describe him as having been a man of uncommon size, tall and strong, patient and industrious, the picture of health, and extremely vigorous even in his old age. He is said to have excelled in playing slow movements—Carlyle speaks of his "heart-thrilling adagios"—and to have possessed considerable execution. His letters show good theoretical musical knowledge and considerable wit.

Philbert is said by Quantz to have been the first distinguished player on the one-keyed flute, and on his skill the early French poet Lainés hasEarly

French

Players written some pretty verses with the refrain, "Sa flûte seule est un concert." He is the "Draco" of La Bruyère's Caractères. He was followed by Hotteterre (see p. 35, ante), Buffardin, and other early players concerning whom we have few authentic details. At the end of the eighteenth century the most celebrated players in France wereHugot A. Hugot (1761-1803) and J. G. Wunderlich (1755-1819), both Professors at the Paris Conservatoire. The former is said to have possessed a fine tone and

immense execution; he wrote some interesting Studies for the flute. Whilst engaged on the preparation of a new Method for the Flute, he was attacked by a nervous fever, in which he wounded himself with a knife and then threw himself headlong from a fourth-storey window, dying in a few seconds. Wunderlich completed the Method, which was long esteemed the best in existence. Wunderlich's most celebrated pupils were Benoit Tranquille Berbiguier (1782-1838) andBerbiguier Jean Louis Tulou (1786-1865). Like Blavet, Sola, and several other flautists of note, Berbiguier was left-handed. In 1813 he left Paris in order to avoid the conscription (as did also Tulou and Camus), but two years later he became a lieutenant in the army, having owing to his small stature to obtain special permission to hold this appointment. In 1830 his devotion to the House of Bourbon got him into political trouble and forced him to quit Paris. He went to live near Blois with a friend named Desforges, a 'cello player for whom he wrote many duets for flute and 'cello. At Desforges' funeral, Berbiguier remarked, "In eight days you will bear me also to the grave"—a prediction that was literally fulfilled. Berbiguier had a peculiarly soft tone but was defective in articulation.

Tulou began to take lessons at the age of eleven, and when thirteen he obtained the second prize forTulou flute-playing at the Paris Conservatoire. The following year the first prize was withheld from him solely on account of his youth. At fifteen he was considered the finest flute-player in all France. In politics Tulou was an ardent Republican. He was strangely neglectful of his playing, frequently mislaying his flute (which is still preserved in the Museum of the Paris Conservatoire) and having to borrow one to play on in public! Once, when about to play a solo at a concert given by Catalini at the Theatre Royal Italien in Paris, he discovered at the last moment that one joint of his flute was cracked throughout; whereupon, on the platform and in the face of the expectant audience, he calmly produced some thread and a piece of wax from his pocket and proceeded to mend the flute, after which he played his difficult solo magnificently. Tulou had a fixed idea that his real vocation in life was not flute-playing but painting. He was passionately devoted to hunting, and somewhat unsteady in his habits. During his rather unsuccessful second visit to London, in 1821, he played at two Philharmonic Concerts, where he was coldly received. In 1829 he became Professor at the Paris Conservatoire, having been passed over ten years previously for Joseph Guillou, an inferior player. He was also created a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. Tulou stuck to the old-fashioned conical flute to the end, preferring one with only four keys. His playing was artistic and finished, remarkable for its liquid smoothness and absence of staccato. He had a rooted objection to double-tongueing; hence his performance, though praised by Böhm, suffered from monotony.

Tulou's principal rival was Louis François Philippe Drouet (1792-1873), the son of a French refugee barber in Amsterdam. One day a musician who was in the habit of getting shaved by Drouet's father presentedDrouet the child with a little flute. Drouet was a marvellously precocious musical genius, and is said to have begun the flute at the age of four and actually to have played a difficult solo at a concert at the Paris Conservatoire when but seven years old. He achieved great success at a concert in Amsterdam in 1807. The only instruction on the flute he ever received was a few lessons in that city as a child. He is said, however, to have studied for eight hours a day for many years, even playing daily for a couple of hours in bed before he rose! In 1808, Drouet was appointed solo flautist to King Louis of Holland, who presented him with a flute of glass having keys set with precious stones. Napoleon the Great invited him to Paris in 1811 and appointed him Court flautist, granting him an exemption from the conscription. Subsequently he belonged to the band of Louis XVIII. Drouet travelled through Europe, creating an immense sensation everywhere. He appeared at the London Philharmonic in 1816, and again in 1832. In March, 1817, he and Nicholson both played at Drury Lane Theatre within ten days of each other. In 1829 he again visited England along with his friend Mendelssohn. He once more visited England in 1841-42, and appeared, by command before Her Majesty Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Buckingham Palace. About 1854 he visited America. Drouet, although he stuck to the old flute and never adopted the Böhm, may well be termed "the Paganini of the flute." He possessed the most wonderfully rapid staccato execution, but his intonation was defective and his style lacked expression. His tone, though brilliant, was deficient in breadth and volume. He totally neglected the full, rich, mellow lower notes of the instrument. "It appears," said a critic, "that to produce the tone at which he aims, nothing more is requisite than to take a piccolo and play an octave below." He could not play an adagio properly, and his whole performance was monotonous. Hence in a contest held in Paris between him and Tulou, the latter gained a decisive victory by his performance of Lebrun's Le Rossignol. He had a wonderful facility in holding notes for an incredible length of time—sons filés, as they were termed; this was partly due to the small bore of his flute and partly to the smallness of his embouchure. His rapid and clear articulation closely resembled double-tongueing, and when he first came to London it set all the amateur flute-players wondering as to how it was produced, and acres of paper were covered with discussions on the subject. It is said to have been really the result of some unusual formation of the mouth, throat, and tongue peculiar to himself. Drouet was a very tall and thin red-haired man, and when playing stood in a very rigid attitude, like a rectangular sign-post. Even his very position gave rise to a controversy. He left behind him over four hundred compositions, mostly rubbish, and is reported to have assisted Queen Hortense in the composition of the famous song, Partant pour la Syrie.

The German family of the Furstenaus produced no less than three generations of famous flautists. CasparThe

Furstenaus Furstenau (1772-1819) was music master to the Duke of Oldenburg. Though a fair performer, he was quite eclipsed by his son, Anton Bernard Furstenau (1792-1852), born at Münster, who at the age of seven played a solo before the Duke, and was presented by him with a magnificent flute. The father and son made several musical tours together between 1803-18, and at their performances the remarkable finish of their execution excited quite a sensation. Anton, who was one of the finest flautists in Europe, was a great personal friend of Weber, in whose orchestra at Dresden he became first flute in 1820, and whom he accompanied to London in 1826. During this visit he played his own Concerto at the Philharmonic. Weber is supposed to have assisted him in some of his numerous compositions for the flute, and no doubt many of the fine flute passages in Weber's operas were written with a view to his flautist friend. Furstenau assisted Weber to undress on July 4th, 1826, the night before the composer died, for which service the latter thanked him, and said, "Now let me sleep"—his last words. Next morning, receiving no reply to his knock at Weber's door, Furstenau had it broken open, and found that his friend's spirit had departed from this world for ever. It was for A. B. Furstenau that Kuhlau wrote many of his compositions. Furstenau and Kuhlau used to play these pieces together. Furstenau's tone was pure, but somewhat thin as compared with Nicholson's, and he abounded in light and shade; his execution was also brilliant. He objected to double-tongueing. He frequently practised before a looking-glass. In later life he toured through Europe with his son Moritz (1824-89), a very precocious flautist, who performed at a public concert in Dresden at the age of eight. The King presented the child with a gold watch for his performance at a Court concert when nine years old. Moritz Furstenau was one of the first German flautists to adopt the Böhm flute, but he was forced—owing to the prejudice of the directors of the Saxon Court Band, of which he was a member—to return to the old flute in 1852.

About 1850 the brothers Doppler appeared. The manner in which they played the most rapid passages (on two flutes) absolutely together, withThe

Dopplers every delicate nuance of expression, caused quite a sensation all over Europe. They visited London in 1856, playing their own compositions: the "Hungarian Concertante" at the Philharmonic concert. The elder brother, Franz (1821-83), born in Lemberg, learned the flute from his father, who was an oboist in Warsaw. He settled in Buda Pesth as principal flautist in the theatre. In 1858 he was appointed conductor at Vienna, and subsequently became professor at the Conservatoire in that city. He composed not only many works of high merit for one or two flutes, but also several overtures, ballets, and operas; one, called Ersébeth, composed by the two Dopplers along with Erkel, was put in rehearsal before it was finished, and the scoring' was only completed on the day of the performance. His younger brother, Carl (1825-1900), who was not so fine a performer, settled in Stuttgart in 1865.

The chief exponents of the French school of flautists after Tulou were Dorus and Demersseman. VincentDorus and

Demersse-

man Joseph van Steenkiste Dorus (1812-96) succeeded Tulou as professor at the Paris Conservatoire. He was one of the first in France to adopt the Böhm system, which was introduced into the Conservatoire in 1838 (it was introduced into the Brussels Conservatoire by Demeurs in 1842), and advocated wood in preference to metal in the cylinder flute. Dorus is said by Böhm to have been a player of taste; he became first flute at the Paris Grand Opera about 1834, and was also a member of the Emperor's band. Dorus played at the London Philharmonic in 1841. Jules Auguste Edouard Demersseman (1833-66), a Hollander by birth, spent most of his life in Paris. Owing to his adherence to the old flute, he was not appointed professor at the Conservatoire. He excelled in double-tongueing and display of all kinds; hence he has been termed "a French Richardson." Though not very artistic, his performance, especially of his own fantasia on Oberon—at a single passage of which he is said to have worked six months before playing it in public—raised the excitable audiences at the Pasdeloup concerts in Paris to the highest state of enthusiasm, causing them to start to their feet and yell their applause. He might be termed "the Sarasate of the flute." His compositions, many of which are still often performed, abound in exaggerated cadenzas,

sometimes occupying whole pages and wandering through half a dozen keys; they require that the

player should, like Demersseman himself, possess most powerful and retentive lungs.

Italy appears to have produced but few flute-players of note: Ciardi and Briccialdi are the only prominent names. Cæsar Ciardi (1818-1877) when he Italian

and

Spanish

Flautistsvisited England in 1847 was encored at the London opera-house, whilst Grisi, Mario, and Tamburini were waiting to be heard. Mr. Broadwood says that he heard Ciardi sustain a crescendo for four consecutive bars of adagio, whereupon Mr. Rudall declared that he "was fit to play before a chorus of angels"—although his instrument was an old Viennese flute with a crack all down the head joint. Guilio Briccialdi (1818-1881), a native of Terni, learned the flute from his father. He ran away from home (to avoid being forced into the Church), with twopence halfpenny in his pocket. After a tramp of forty miles he reached Rome, and entered the Academy of St. Cecilia, where in course of time he became Professor. He subsequently visited the principal cities of Europe (London in 1848) and America, and was Professor at Florence when he died. He was a brilliant performer, although he held his flute extremely awkwardly. He adopted the Böhm. His tone is reported to have been poor. Briccialdi was a remarkably handsome man. Both these Italian players produced a peculiar singing effect, and excelled in playing from fortissimo to pianissimo and vice versa. They possessed

much power of colouring, and elegance of execution, the true Italian refinement of taste—broad, not finikin

like the modern French school, in its finish. They both composed many solos for the flute, some of which are

excellent. The only Spanish flautist deserving notice is José Maria del Carmen Ribas (1796-1861), who served

as a soldier under Wellington in the Peninsular War, and fought at the battle of Toulouse. Ribas played

the flute and the clarinet equally well—often at the same concert—and also played the concertina. For many

years he was a leading orchestral player on the flute in London; playing at the Philharmonic Concerts (1838-41)

and the Italian opera. He was the first to play the famous Scherzo in Mendelssoln's Midsummer Night's Dream

in England, and the composer was so pleased at the rehearsal that he asked Ribas to play it over three

times, saying that he had no idea it would be so effective. Ribas played the old flute and possessed a powerful tone.

A remarkable and eccentric genius, whose name is familiar to every flautist, Adolf Terschak (1832-1901),Terschak was born at Hermannstadt in Transylvania, and studied at the Vienna Conservatoire. In 1863 he had a quarrel with Böhm, whose flute he never would adopt. Terschak was a born "globe-trotter," and gave flute recitals in all sorts of out-of-the-way places, which had never before been visited by any European flautist of note. Much of his life was spent in Arabia, Astrachan, Siberia, Korea, China, Japan, and

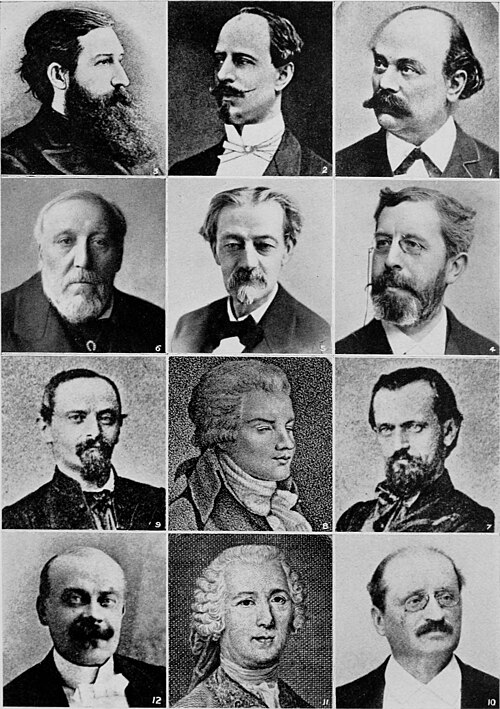

Famous Flautists.— III.

Top Line—Sidney Lanier, A. de Vroye, Wilhelm Popp.

Second Line—Henry Nicholson, John Kyle, Fr. Taffanel.

Third Line—Franz Doppler, Fr. L. Dulon, Carl Doppler.

Fourth Line—Joachim Andersen, J. J. Quantz, E. Köhler.

Iceland. In 1897 he toured in Central Asia, and was almost shipwrecked in crossing the Caspian Sea; suffering a very severe illness in consequence. He composed a large number of works for the flute, an opera Thais, and many other orchestral and vocal works. As a reward for his Nordlands Bilder (op. 164) the King of Norway created him a member of the Order of St. Andrew. He also possessed several other foreign decorations. As regards his playing, his power and execution were immense, but his tone was coarse and windy; moreover he was generally out of tune, and in 1878 his attempts to tune with the orchestra at the Crystal Palace so signally failed that he left in disgust. He was a tall, strong, handsome man, but in later life he suffered much from his eyes, and his health broke down. He died in Breslau.

To turn once more to the French school:—Dorus was succeeded by Joseph H. Altès (1826-1899), a pupil of Tulou at the Paris Conservatoire, where he gained first prize in 1842. He subsequently became first flute at the Opera and professor at the Conservatoire. He was succeeded by Paul Taffanel (1844- 1908), born at Bordeaux, the greatest French flautist of recent times. Taffanel began to learn the flute from hisTaffanel} father at the early age of seven. When ten years of age he made his début at a public concert in Rochelle, with great success. Through the influence of an amateur flautist the lad was placed in Dorus' class at the Paris Conservatoire in 1860; where he carried off the first prize for flute-playing, and also for harmony, counterpoint, and fugue. In 1871 Taffanel was appointed first solo flute in the Grand Opera, Paris, and in 1887 became conductor. Ten years later he was appointed conductor at the Conservatoire. In conjunction with Lalo, Armingaud, and Jacquard, he in 1872 founded the Société Classique, a string and wind quintett Society which continued to give concerts in Paris and elsewhere for fifteen years; by their perfect ensemble this Society raised the standard of wind-instrument chamber playing to a pitch never hitherto attained. Under the stress of his arduous duties as musical director at the Paris Exhibition, 1900, his health broke down, and in the following year he resigned his position at the Conservatoire. His execution was rapid and brilliant, his tone extremely soft and velvety, and his playing full of soul, expression, and refinement. He was a member of the Legion of Honour and of many other foreign orders.[4]

SECTION II.—BRITISH PLAYERS.[5]

Previous to Nicholson, very few English names appear in the list of eminent flautists. Concerning the Guys and Lanlers, etc., who played flutes in Charles the First's band, we know practically nothing. Burney mentions one "Jack" (his real name wasEarly

Performers Michael Christian John) Festing in 1731 as "good on the German flute"; and Joseph Tacet, who is credited with the invention of certain keys and who wrote some flute music, is mentioned in Miss Burney's Diary (May 5th, 1772) as a player, but little is known about him. Our earliest native player of note concerning whom any details are preserved would appear to have been Andrew Ashe (c. 1758-1841), a native of Lisburn in the County Antrim, Ireland. Ashe travelled much in early life along with Count Bentinck, and becameAshe proficient on several instruments, studying the flute from Mozart's friend Wendling (see p. 135, ante). He subsequently became first flute in the Brussels Opera House, having defeated Vanhall, the holder of that position, in a public trial of skill. Returning to Ireland in 1782, Ashe played at concerts in the Dublin Rotunda and at the Exchange Rooms in Belfast, where on November 29th, 1789, he performed a concerto of his own composition, introducing Robin Gray, and also took part in a duet for flute and clarinet, on Arne's Sweet Echo. Salomon in 1791 came over to Dublin specially to hear him, and immediately engaged him as first flute for his famous London Concerts (where some of Haydn's symphonies were produced). On Monzani's retirement, Ashe filled his place at the first flute desk in the Italian Opera. He afterwards conducted the concerts in Bath for twelve years. Ashe was an original member of the London Philharmonic Society, being their only flute in 1813, and played there in several Chamber pieces in 1815-16. He was nominated a Professor in the Royal Academy on its foundation in 1822; but returned to Dublin, where he was residing at the time of his death. Ashe was a remarkably healthy man, and used to boast that in his whole life he had only spent a single guinea in doctor's fees. He was one of the first to adopt the six-keyed flute, and is said to have possessed a full, rich tone and much taste and judgment.

Probably the most striking flautist that England ever produced was Charles Nicholson (1795-1837), born inCharles

Nicholson Liverpool, the son of a flute-player. He was practically self-taught. A handsome man of commanding stature and endowed with great muscular power of chest and lip, Nicholson's popularity in England was absolutely unparalleled. He had more applicants for lessons at a guinea an hour than he could attend to. He played in the orchestra of Drury Lane, at the Italian opera, and the Philharmonic Concerts (1816-36). His style was the very antithesis of the French school, and he was by no means so highly thought of on the Continent. Fetis says he was inferior to Tulou in elegance and to Drouet in brilliant execution. He had a very peculiar, strong reedy tone—something between the oboe and clarinet—grand, but so hard as to be almost metallic. His lower notes were specially powerful and "thick," and resembled those of a cornet or an organ. His double-tongueing was extremely effective, and a great feature in his performance was his whirlwind chromatic rush up the instrument from the lowest C to the very topmost notes in alt.; he himself compared it to the rush of a sky-rocket, whilst his descending scale has been likened to the torrent of a waterfall. He simply revelled in difficulties, using harmonics freely, and also the vibrato and the "glide." He adopted very large holes (Böhm, whose fingers were small and tapering could not cover them), and had various excavations made in the wood of his flutes to fit his fingers and joints. He frequently performed in public without any accompaniment, and is said to have excelled in an adagio, his playing abounding in contrast and variety. As a rule, he played his own compositions—mostly rubbishy airs with well-nigh impossible variations, embellishments, cadences, cadenzas, and shakes of inordinate length. His flute had at first six, and later seven keys. On one occasion a duel was arranged between him and Mr. James, the author of A Word or Two on the Flute, but it never came off. Nicholson's posing and tricks gave rise to many satires, in one of which he is called "Phunniwistl." After all his vast popularity, Nicholson, owing to his extravagant habits, died (of dropsy) in absolute penury. He was appointed professor of the flute at the Royal Academy of Music in 1822.

On Nicholson's death he was succeeded by his pupil Joseph Richardson (1814-62), popularly termed "The Ambidextrous," or "The English Drouet," in consequence of his rapid enunciation and tours de force. He was physically a great contrast to Nicholson, beingRichardson a remarkably small man. For many years he was solo flautist in Jullien's band, and afterwards in Queen Victoria's private orchestra. He played at the Philharmonic Concerts in 1839 and 1842. Richardson is said to have practised all day and almost all night, and acquired a marvellous dexterity. He had an exceptionally fine embouchure, but his tone, though brilliant and very "intense," was hard, small, and thin. He is said to have been "cold" in slow movements. On one occasion Richardson and Nicholson played the same solo—Drouet's "God Save the King "—at two rival concerts on the same evening in Dublin.

Richardson was succeeded at the Academy by John Clinton (1810-64), an Irishman, who was one of theClinton

and

Pratten first to teach the Böhm flute in England. Though his tone was coarse and his tune defective, he was for many years first flute in the London Italian Opera, where he was succeeded in 1850 by Robert Sydney Pratten (1824-68), who also took Richardson's place in Jullien's band when the latter retired. Pratten, who was self-taught, played all over Europe with applause. He had a great objection to extra shake-keys, and would not have the one to shake C♯ D♯ on his flute. Sir Julius Benedict was once conducting a rehearsal of an overture of his own which contained this shake as a rather prominent feature. Pratten shook C♯ D♯ very rapidly, and Sir Julius in delight exclaimed that he had never before heard that shake properly made, whereupon the entire orchestra burst out laughing. Pratten became suddenly very seriously ill whilst playing the obligato to "O rest in the Lord," in the Elijah at Exeter Hall in November, 1867. He played on to the end of the item, but had then to leave the orchestra, never to play again in public.

Pratten's great English contemporary flautist, Benjamin Wells (1826-99), a pupil of Richardson and Clinton, was at the age of nineteen appointed first flute at the Royal Academy concerts, andWells was congratulated on his performance by the Duke of Wellington, in company with Mendelssohn. He was an intimate friend of Balfe, and played in the orchestra on the first performance of The Bohemian Girl at Drury Lane in 1843. Wells once performed a fresh solo from memory every evening for fifty consecutive nights. He played in Jullien's band, and was for some time president of the London Flute Society, and also Professor at the Academy. He was the representative of the Böhm flute at the great Exhibition of 1851, where Richardson performed on Siccama's model.

"Seventy years a flautist!" Such was the proud boast of old Henry Nicholson (1825-1907), the most prominent figure in the musical world ofHenry

Nicholson Leicester for over half a century, and probably the last survivor of the orchestra that played at the first performance of the Elijah (1846), conducted by Mendelssohn himself. On that occasion the great composer inscribed his autograph in Mr. Nicholson's flute case, which also contained the autographs of numbers of other leading musicians of the past and present. This veteran flautist also played (in 1847) under the bâton of Berlioz, on the occasion of the dèbut of Sims Reeves, with whom he formed a life-long friendship. Mr. Nicholson began his musical career at the age of nine, but never received any regular musical tuition. At the age of thirteen he played flute solos in public. When twenty-two he became a member of Jullien's famous orchestra. He subsequently played at the opening of the great Exhibition of 1851, at the Covent Garden Opera, and at the first Handel Festival in 1857; he continued a member of the Festival orchestra till 1890. Mr. Nicholson organized a long series of concerts in his native town; he also acted as musical conductor at the Dublin Exhibition of 1872. When in 1882 he appeared at St. James's Hall along with Mme. Marie Roze, Punch described the performance:—"A mocking-bird, perched on his own flute, and hopping from note to note in the most delightfully impudent and irritating manner. Shut your eyes and there was the mocking-bird, open them and there was Mr. Nicholson. What a pity he couldn't appear in full plumage with a false head and tootle on the flootle through his beak!" As a player, Henry Nicholson was remarkable for his pure ringing tone and his extraordinary facility of execution. He played in public till very shortly before his death. In his younger days he was an excellent cricketer, and scored against crack elevens.

Oluf Svendsen (1832-88), a native of Christiania, was the son of a military bandmaster, and played first flute in the theatre there at the age of fourteen.Svendsen

and Vivian He had two years before joined the Guards band as first flute. He first learned from Niels Petersen, of Copenhagen, and subsequently from Reichert at the Brussels Conservatoire. In 1855 he came to London to play for Jullien at the Covent Garden promenade concerts, and settled in England. Svendsen held the post of Professor at the Royal Academy of Music for twenty years, was first flute at the Crystal Palace for some time, and for many years played at all the principal concerts in and about London, joining Queen Victoria's private band in 1860, a post which he retained till his death. He played in the Royal Italian Opera from 1862 till 1872, and frequently appeared at the Philharmonic (1861-85). His wife was a daughter of Clinton and a fine pianist. Personally, Svendsen was a quiet, modest man, with agreeable manners. He was very fond of his native land, and often visited it. He produced a beautiful tone from his silver flute, and was not only a fine orchestral player, but also excelled as a soloist. The great features in his playing were his exquisite, artistic phrasing and the singing effects he produced, like those of Ciardi and Briccialdi, I shall never forget the way in which, a few months before his death, he led a performance of one of Gabrielsky's quartetts for four flutes, in which I had the honour of taking part. Svendsen's principal pupil was A. P. Vivian (1855-1903), who inherited much of the manner of his master, and became Professor at the Royal Academy and principal flute at many leading concerts in London.

There are in England to-day many fine flautists. The first name that will occur to every flute-player isLeading

Flautists

in England

To-day that of John R. Radcliff (b. 1842), who began his career, at the early age of seven, on a penny whistle, having stopped up the top end with a cork and improvised a mouth-hole at the side. He played in public when twelve years old. Mr. Radcliff mastered the Böhm system in a fortnight. His tone is remarkably powerful, recalling that of Charles Nicholson. Next in seniority stands Edward de Jong (b. 1837), a Hollander who has made England his home for very many years past. He arrived at our shores with the magnificent sum of 1s. 6d. in Dutch money in his pocket! After playing in Jullien's band he joined the Hallé orchestra, of which he remained a distinguished member for fifteen years. Mr. E. de Jong is eminently successful as an orchestral conductor. In his hands the flute almost becomes articulate; it literally sings, especially on the lower register. Other players of the older generation still happily with us are Jean Firmin Brossa, born in Geneva in 1839, for many years first flute of the Hallé orchestra and possessed of wonderfully pure, delicate tone and a marvellous pianissimo; and William L. Barrett. On

Famous Flautists of To-day.

Top Line—J. Radcliff, Eli Hudson, W. L. Barrett.

Second Line—F. Brossa, V. L. Needham, Miss Cora Cardigan.

Third Line—E. de Jong, F. Griffith, E. S. Redfern.

Fourth Line—D. S. Wood, A. Fransella.

one occasion, when the Royal Italian Opera Company was about to perform Lucia de Lammermoor for the début of Mdlle. Fohstrom, the mad scene had not been rehearsed. What was to be done? Barrett was equal to the emergency. Standing outside the prima donna's doubly-locked door during the entre-act he modestly tootled the obligato through the key-hole, whilst the lady warbled the voice part as she dressed!

The principal players of the younger generation are Albert Fransella (b. 1866 in Amsterdam), the well-known soloist of the Queen's Hall orchestra, a virtuoso to his finger-tips, who when quite a lad attracted the attention of Brahms; Eli Hudson, who began the piccolo when aged five and performed in public at seven! a remarkable soloist, gifted with marvellously fluent, clean execution, and extremely powerful, even tone; Vincent L. Needham, the present first flute of the Hallé orchestra, whose rapid double-tongueing once caused a gentleman at a concert to get up out of his seat and walk round the stage to see if there were not another flute-player hid behind the scenes; Frederick Griffith, probably the greatest flautist Wales has ever produced, who by practising always pianissimo attained exquisite delicacy of tone; E. Stanley Redfern, who possesses a rich, smooth tone and remarkable technique; and Daniel S. Wood, of the London Symphony orchestra. Space forbids my mentioning even the names of many other fine players now before the British public.

- ↑ There is a fine picture by Menzel in the Berlin National Gallery of one of the concerts, with Frederick standing at his desk playing the solo part, and Carl P. E. Bach at the pianoforte. Amongst other notable pictures in which the flute figures prominently are Van Ostade's Le Trio (Musée de Bruxelles), Ferret's Musicien Annamite (Musée du Luxembourg), and Watteau's L'Accord Parfait (in all of which the flute-player is left-handed); David's Le Compositeur de Vienne (Musée Moderne de Bruxelles), Weber's Loisirs de Monsigneur (Paris Salon, 1908), Rosselli's La Triomphe de David (Louvre), Mazzani's A Difficult Passage, and Millais' An Idyll (fife); also in pictures in Punch for Jan. 8th, 1887; Dec. 6th, 1888; Jan. 4th, 1905; and May 2nd, 1906.

- ↑ Mr. James Mathews (see p. 72, ante) christened his gold flute "Chrysostom"—the golden-mouthed, and an American flautist of some notoriety (Mr. Clay Wysham) named his flute "Lamia."

- ↑ The flute can boast that it is the only instrument on which a great sovereign has ever attained proficiency and for which a monarch has composed. Frederick was by no means the only flautist of Royal blood. The infamous Nero was a flute-player of some note in his day; King Auletes of Greece, the last of the Ptolemies and father of Cleopatra, played in public contests with professional flute-players and was inordinately proud of his performance. Our own bluff King Hal delighted in the flute and played it daily, says Holinshed (1577). Seventy-two "flutes" are mentioned in the Inventory of his Wardrobe, 1547; some are of ivory, tipped with gold, others of glass, and one of wood painted like glass. The same list mentions six fifes and numbers of recorders. Francis I. of Austria (c. 1804), Joseph I. of Hungary (1678-1711), and Frederick, Markgraf of Brandenburg—Culmbach—Bayreuth (1711-63), were flute-players. Albert, the Prince Consort, played well, and took lessons from Benjamin Wells. Prince Nicholas of Greece is an accomplished flaulist, and has written a concerto on themes furnished by the compositions of Frederick the Great, some of whose instruments he possesses. The Count of Syracuse, brother to the King of Naples, learned the flute from Briccialdi in 1837. Moreover, Carmen Sylvia, the Queen of Bohemia, is whispered to be a flautiste. Did not one of the English Georges also play it?

- ↑ Amongst other players of note (not referred to elsewhere in this volume) who appeared between 1770-1850, the following deserve mention:—Saust, Dressier, Soussmann, Kreith, Heinemeyer (London Philharmonic Concert, 1838), Krakamp (German); Guillou (London Philharmonic Concert, 1824), Lahou, Remusat (French); Reichert (Belgian); Sola (Italian); Card, Saynor (English).

- ↑ In this section I include players who, though not of British birth or parentage, have permanently settled in England.