The Story of the Flute/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III.

THE TRANSVERSE FLUTE.

Sec. I.—Was it known to the Greeks and Romans?—The Chinese—India—Early representations and references—The Schweitzerpfeiff—Virdung—Agricola—Prætorius—Mersenne's description—In England.

Sec. II.—Flutes with keys—The D♯ key—Hotteterre—The conical bore—Structure of early flutes—Tuning slides—Quantz's inventions—The low C keys—Further keys added—Tromlitz's inventions—Open keys—The eight-keyed flute—Capeller and Nolan's keys.

SECTION I. — KEYLESS FLUTES.

The origin of the transverse or side-blown flute is involved in much obscurity. It was formerly thought to be comparatively modern, and Germany, Was it

known to

the Greeks

and

Romans?Switzerland, and England have each been termed its birthplace. But more recent discoveries tend to prove that the transverse flute—though not so usual as the vertical flute—was probably known in Europe early in the Christian era. Possibly it was known to the ancient Greeks and Romans; but if so, it is very remarkable that no clear allusion to it can be found in any of the writings of either nation. Care must be taken not to confuse it with the plagiaulos (see p. 13, ante) or with ancient pipes blown across the open upper end and held sideways, which are never depicted with a lateral mouth-hole, and never have the end of the tube protruding beyond the mouth of the player.

Ward, in his Word on the Flute, citing Hawkins, mentions an engraving of a tesselated pavement in a temple of Fortuna Virilis at Rome, built by Sylla (c. 78 B.C.), in which he says there is a representation of a player with a transverse pipe "exactly corresponding with the German flute"; and Montfaucon, in his L'Antiquité Expliqueé gives two copies of bas-reliefs of a similar kind. Kircher (1650) also represents transverse flutes as known to the Egyptians many centuries before Christ. But the correctness of these statements and the accuracy of the copyist are extremely doubtful. In the case of ancient statues (such as The Piping Faun) the flute with a lateral mouth-hole is probably invariably a modern restoration. There is, however, in the British Museum a fragmentary flute found by Sir Charles Newton in a tomb at Halicarnassus, and one of the fragments has what certainly appears to be a side-blown mouth-hole cut in a wedge-like excrescence, beyond which the tube (of ivory) projects. But no undoubted and complete specimen of a real transverse side-blown flute, or absolutely authentic contemporary representation of such an instrument, has ever been found among the numerous relics of the ancient Greeks, Romans, or Egyptians. If the transverse flute was known in pre-Christian Europe, it certainly disappeared completely for many centuries.

Transverse flutes were known to the Chinese and to the Japanese from time immemorial, and Dr. Lea Southgate considers that probably the Known to

the Chinese,

etc.European transverse flute is derived from the Chinese Tsche, but he gives no evidence in support of this startling theory. In India also the instrument was certainly known at a very early period. Some carvings of the god Krishna (to whom the natives attribute the invention of the flute) on the eastern gateway of Sanchi Tope in Madras, and various ancient monuments in Buddist Temples in Central India, dating about 50 B.C., contain representations of transverse flutes. It is depicted on the Tope of Amaravati (now in the British Museum), which dates from the first century.

I can find no substantial evidence of the existence of transverse flutes in Europe till the tenth and eleventh centuries. Such instruments are portrayed Early

European

Repre-

sentations

and

Referenceson some ivory caskets of the tenth century Early in the National Museum at Florence, also in some Greek MSS. of the same date in the Bibliotheque National in Paris, and in an illuminated Byzantime MS. of the eleventh century in the British Museum. There is in the oldest portion of the Cathedral of Kieff, in Russia, a picture stated to have been painted early in the eleventh century, which includes a transverse flute. We find pictures of transverse flutes in Hortus Deliciarum, written in the twelfth century by Herrade de Landsberg, Abbess of Hohenbourg, and in the Codex to the Cantigas de Santa Maria, an illustrated Spanish MS. of the thirteenth century, written by King Don Alonzo of Sabio and preserved in the Escurial at Madrid. This last-mentioned picture has been reproduced in Don F. Aznar's Indumentaria Espanola, 1880, in Don Juan Riano's Notes on Early Spanish Music (App. Fig. 8, p. 118), London, 1887, and also in English Music, p. 139. It is to be noticed that the player is left-handed. Another early picture of a transverse flute occurs in The Romance of Alexander by Jehan de Guise, dated 1344, now in the Bodleian Library. There is in the Ashmolean Museum at Oxford a china basin from Urbino, dating about 1600, depicting a feast, which portrays a long transverse flute, and beside the player lies a case for the instrument.

A Provençal poet, musician, and composer, named Guillaume de Machault, born c. 1300 (whose works were discovered in 1747), in his La Prise d'Alexandrie, includes "flaüstes traverseinnes" in a long list of the instruments of his day. This would appear to be the earliest known mention of the transverse flute in literature. It is also mentioned by Eustache Deschamps, another French poet of the fourteenth century. It certainly was well known in the time of Gallileo; and Rabelais, writing about 1533, describes Gargantua as playing on the Allman [i.e., German] flute with nine holes (Bk. I., ch. 23).

Though the earliest form of the transverse flute in mediæval Europe is generally said to be of Swiss origin, and was called Schweitzerpfelff, the Germans appear to have developed it more than any other nation (though the French were the first to produce great players), and our earliest informationReferences

in Early

Treatises

on Music;

Virdung respecting it is to be found chiefly in German treatises. We find an engraving of the instrument (there called Zwerchpfeiff) in the Musica Getutscht und Auszgezogen of Sebastian Virdung, published at Basle in 1511. It will be noticed (Page 30, Fig. 1) that the mouth-hole is very small, and is round; that the finger-holes are very far removed from it, being all equal distances apart and very close to each other; and that the tube is a long, slender cylinder. Certainly the flute here depicted does not look as if it was drawn accurately to scale from an actual instrument. Unfortunately, Virdung did not give any detailed description either of its construction or of the manner of playing it. The Musurgia seu praxis Musicœ (1536) of Ottomar Luscinius (or Nachtigall) is practically a translation of Virdung's work into Latin, with identical illustrations. He mentions five varieties of flutes:—The Chalamen and Bombardt (like the modern clarinet), the Helvetian (like the old English flute-à-bec), the Schwegel (or whistle), and the Zwerchpfeiff.

The next important notice of the flute is to be found in Musica Instrumentalis Deudsch, first published by Georg Rhaw at Wittemburg in 1528 andAgricola enlarged in 1545, compiled by Martin Agricola (whose real name was Sohr, or Sore). It gives engravings of Schweitzerpfeiffs of different lengths— discantus or soprano, alto, tenor, and bass. They are very similar to the instrument portrayed by Virdung, even to the two little lines drawn across the tube immediately above the mouth-hole. In this work we meet for the first time with a diagram (Page 30, Fig. 2) showing the fingering of the holes, and very curious it is. The D hole[1] is to be covered by the first finger of the left hand, and the G hole with the first finger of the right hand. According to the present English numbering of the fingers, this could only be done by crossing the hands palm to palm, a position in which it would be impossible to play. But possibly the early German numbering of the fingers began with the little finger as number one. Even so, it is hard to understand this diagram: what was to be done with the first finger of each hand?

All these early illustrations (which appear to be copied from one another) represent the flute as a cylinder of equal diameter throughout, with very small finger-holes and without any joints. ThePrætorius two lines above the mouth-hole are evidently only for ornament. The earliest illustration of a jointed flute is to be found in the Theatrum Instrumentorium seu Sciagraphia of Michaelis Prætorius (i.e., Schultheis, or Schultz), published at Wolfenbuttel in 1615-20, in illustration of the author's Syntagma Musicum. Prætorius introduces pictures of four flutes (of which he gives the dimensions), and the largest of these (Page 30, Fig. 3) has apparently a head-joint separate from the body of the instrument, the diameter being larger at the joint. This, however, may be mere ornamentation. Another novelty is to be noticed—viz., the first three holes are separated from the second three by a considerably larger space. Possibly this division always existed in these early flutes, but if so, it was not shown in any of the earlier representations of the instrument.

Much the fullest description of the early flute, however, is that given in Harmonic Universelle, the great illustrated work of Father Marin Mersenne,Mersenne'sDescription of the Order of Minorites, published in Paris in 1636-37. In Vol. 11., Part v., he treats of the various kinds of flute at considerable length, terming the transverse flute "Fistula Germanica," or "Helvetica," whilst he calls the flute-à-bec "Fistula Anglicis." He gives an illustration of "one of the best flutes in the world" (Page 30, Fig. 4, which I reproduce from the copy of his book in the Library of Dublin University)—a transverse flute which is bent curiously towards the open end. He also gives full explanations, which are very interesting, as they are the earliest detailed account of the instrument and the method of playing it. The tube was 23.45 inches long and cylindrical throughout, with a cork in the head, the embouchure being 3.2 inches from the top end. The bore of the tube was slightly less than that used at present. It is apparently without joints, the six finger-holes, which are larger than those in

Keyless Flutes.

from left to right:

Fig. 1—Virdung's Zwerchpfeiff, 1511.

Fig. 2—Agricola's Schweitzerpfeiff, 1545.

Fig. 3—Prætorius' Bass Querflote, 1620.

Fig. 4—Mersenne's Fistula Germanica, 1637.

Flutes with Keys.

from left to right:

Fig. 1.—Hotteterre's Flute, 1707.

Fig. 2.—Quantz' Flute, 1726.

Fig. 3.—Tromlitz' Five-Keyed Flute, c. 1803.

Fig. 4.—Eight-Keyed Flute, c. 1806, with the Names of the Alleged Inventors of the Various Keys, ect.

"Air de Cour " from Mersenne (as transcribed into modern notation; in the original each flute has a separate stave.)

The exact date at which the transverse flute was first used in England is not known; but certainly the fife was in use in the time of Henry VIII. TransverseIntroduc-

tion into

England flutes are depicted in an engraving to Spenser's Shepherd's Calendar, dated 1579; in Ghieraert's picture of the Marriage Feast of Sir Henry Unton, painted about 1596, and now in the National Portrait Gallery—in both cases the player is left-handed—and in a contemporary picture of Sir Philip Sidney's funeral (now in the Heralds' College); and such instruments are mentioned in an inventory of Hengrave Hall, Sussex, in 1602. The earliest English description of the transverse flute I have met with is in Bacon's Sylva Sylvarum: having described the method of blowing the recorder, he says, "Some kinds of instruments are blown at a small hole in the side, . . . as is seen in flutes and fifes, which will not give sound by a blast at the end, as recorders do." This was written certainly before the end of 1626, as Bacon died in that year, and the book was published posthumously in the following year.

SECTION II. — FLUTES WITH KEYS.

Hitherto all flutes were made of wood (generally boxwood), with a round mouth-hole—the oval mouth-hole did not appear till about 1724—with six finger-holes only, without any keys, and pitched in the major diatonic scale. The application of additionalThe D♯

Key holes stopped by keys dates from about 1660-70, when Lulli first introduced the flute into the orchestra. About that date some now unknown inventor, probably of French origin, introduced the D♯ key, which is found on the Chevalier flute (c. 1670), and is shown in a picture dated 1690. Virdung, Agricola, Mersenne, Prætorius, and Bartholinus (1677) all give representations of a bass flute-à-bec with a key enclosed in a perforated casing for a low note (see Fig. 11); but this device does not appear to have been applied to transverse flutes of the period. The invention of this D♯ key was the first really important step in the improvement of the flute. The innovation was at once adopted by Philbert (who is often credited with its invention), by Michel de La Barre, by Hotteterre, by Buffardin, and by Blavet—the earliest great players of whom we have any record. From the picture of a flute of the period (see p. 31, Fig. 1) given in Hotteterre's Principes de la Flûte traversière, published in 1707, it isHotteterre evident that the key was supported by means of a raised wooden ring left round the tube. A groove cut in this ring admitted the key, which moved on an axle, and was kept closed by a spring under the finger-end of the key. This system of key mechanism was also used for other keys subsequently introduced, and is still met with in a modified form in cheap flutes, which have the pin-axle supported between two knobs of wood, the remainder of the ring being cut away. The author of this book—the first complete book of instructions for the flute now known—was called Hotteterre-le-Romain, because he spent part of his early life in Rome. He came of a numerous French family of wind instrument makers and players, many of whom were members of the band of Louis XIV. He has been hitherto confused with an earlier member of the family named Louis, who was Royal flute-player at Court in 1664; but M. Ernest Thoinan, in his book Les Hotteterre et les Chedeville (Paris; Sagot, 1894), has satisfactorily proved that his Christian name was Jacques, that his father's name was Martin, and that he was born in Paris. From the same authority we learn that in 1708 he played his compositions for the flute before the King, who granted him a Document of Privilege, and that he lived in

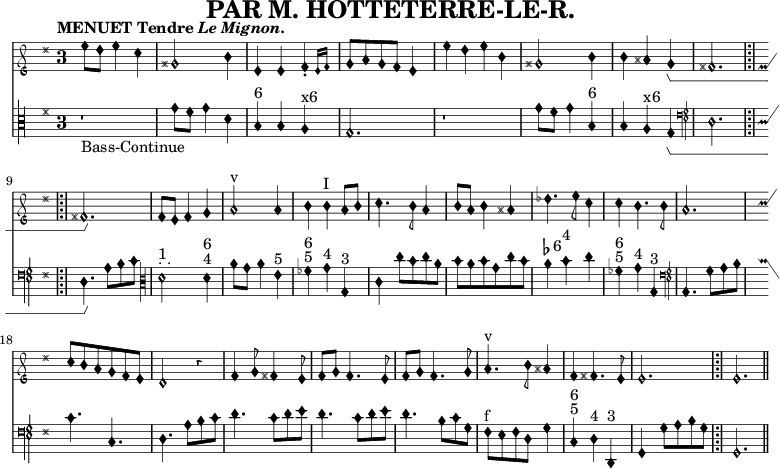

Hotteterre-le-Romain. (By Benard Picart.)

Facsimile of a page of one of Hotteterre's flute solos with bass. In the original the lines are broken and very uneven, and it is difficult to tell what the notes really are.

said to have been the first to play the transverse flute in the opera at Paris, c. 1697. Several of his contemporaries bear testimony to his powers as a performer, and one, writing in 1702, says he "taught the instrument to lament in so affecting a manner in mournful airs, and to sigh so amorously in those that are tender, that all are moved by them." The fact that several editions (some pirated) of his Principes appeared in various countries in rapid succession bears witness to the popularity of the flute, which Hotteterre in his preface terms "one of the most agreeable and fashionable of instruments."

The size of the finger-holes was also reduced about the same time, and shortly afterwards the number of joints was increased; a boxwood one-keyedStructure

of Early

Flutes flute made for Quantz before 1724 by F. Boie, a well-known maker, consisted of four separate pieces.[2] These early flutes generally had several—sometimes as many as six—interchangeable middle sections of various lengths, which were used for the purpose of altering the pitch. This device was still used in 1791, and is mentioned in Florio and Tacet's Instruction Book. Pratten tried it in 1867. Sometimes also the foot-joint was made in two pieces, sliding into each other, which could be pulled out or pushed in, so as to lengthen or shorten the joint about half an inch according as a longer or shorter middle section was employed. ThisTuning

Slides was called a "Register," and by its means the pitch could be altered an entire tone. Quantz before 1752 made an additional long pin-and-socket joint in the head-piece, so that it could be lengthened or shortened at will. This tuning-slide was originally made of wood, and it was found that when drawn out there was a considerable cavity left in the inside of the tube, rendering the bore wider at that point; this affected the tone. To remedy this defect Quantz had a number of rings of wood of various widths to slip into this cavity and fill it up. These rings are still occasionally used in old flutes, but they are unsatisfactory and troublesome. The adoption of a thin metal slide, leaving a very trifling cavity, has practically remedied this defect. Böhm objected to a metal slide on the ground that the close combination of metal with wood caused unequal and disturbed vibration, and produced a disagreeable harshness of tone. On his flute of 1832 he therefore used wooden rings. Theoretically, in order to alter the pitch correctly throughout the entire instrument, the position of each hole should be varied, which is, of course, impossible. By means of the slide the pitch can be varied about the eighth of a tone without putting the flute appreciably out of tune. In most modern flutes the tuning slide is formed by a projection at the top of the second joint.

In 1726 Quantz added a second hole and closed key (Page 31, Fig. 2), which, he claimed, produced theQuantz's

Inventions E♭ more correctly than the D♯ key, and thus rendered the common chords of E♭ and B♮ more perfectly in tune. One hole had an aperture larger than the other, and by using one or other the tone and tune of certain defective notes was corrected. This additional key, though adopted by Tromlitz, was of no practical value. It never became general, and was only used in Germany, where it survived for about eighty years. Tromlitz credits Quantz with the invention of a screw-stopper at the head of the flute, by means of which the position of the cork in the head joint could be adjusted. Quantz, however, does not himself lay any claim to this invention, which appeared before 1752, as also did the brass-lining of the head-joint.

The table of fingering given by Quantz ascends to A′′′♮ in alt., whilst that in Diderot's Encyclopœdia (1756) goes up to the D in alt. above this (being, in fact, a note higher than the present Böhm flute), but he adds that the last five semitones cannot be sounded on all flutes. Quantz possessed a flute, made by I. Biglioni, of Rome, which had an additional open key for the low C♯. But he made noThe Low

C Keys claim to its invention, telling us that about 1722 both low C♯ and C♮ open keys were added to flutes, with a lengthened tube. He objected to this innovation (as did also Wendling, his successor), and it was for a time abandoned as detrimental to tone and intonation; both keys were, however, revived by Pietro Grassi Florio about 1770. Florio was first flute in the orchestra of the Italian Opera in London. He used to hang a little curtain to the foot-joint of his flute in order to conceal these keys, which he wished to keep secret. The French player, Devienne, in 1795 objected to Florio's keys as being out of place in the instrument, and having no power, but they are now universally used on all concert flutes.

The next keys to be added were those for F♮, G♯, and B♭. The exact date of this innovation is not known. One Gerhard Hoffmann is reported to have used the G♯ and B♭ keys in 1722. They first appeared in LondonFurther

Keys

added shortly after 1770. By their means all the semitones (except C♮) could be played without fork-fingerings. They also greatly improved the tone of several other notes. It is a matter of wonder how the chromatic passages and shakes found in the flute compositions of Quantz and other early composers could have been played without them. The name of the inventor is uncertain. Ribock, Lavoix, and Mahillon ascribe the short F♮ key to the somewhat mythical Kusder in 1762. Some ascribe all three to Tromlitz, and others (with considerable probability) to Joseph Tacet, who certainly was one of the first to employ them. Tacet, who also experimented with large finger-holes, such as Nicholson afterwards tried, was a flute-maker, player and composer of some note. He was a grandfather of Cipriani Potter; and Richard Potter (the well-known London flute-maker) adopted these keys on a flute made in or before 1774, on which Vanhall performed at The Hague, and which he subsequently sold to Ashe, the Irish flautist. This doubtless is the instrument referred to in the Encyclopédie Methodique (1785)—"It is pretended that an English musician has constructed a flute with seven keys in order to obtain all the semitones." Potter in 1785 took out the first English patent for improvements in the flute; it included these keys, also a metal tuning-slide, a screw-cork in the head-joint, and conical metal valves on the keys. He, however, makes no claim to have invented any of these improvements—they were all known previously. Ribock in 1782 mentions these three keys as being in general use in Germany.

The next step was the addition of a short C♮ key, placed across the tube. Ribock claims to have invented it before 1782; others ascribe it to Petersen of Hamburg, or to one Rodolphe, of whom nothing is known. This key was altered some time before 1806 into a long key (inventor unknown) running along the side of the tube and opened by the first finger of the right hand.

Strange to say, these additional keys, which greatly improved the instrument—though still very defective—were much objected to, the existing flute being considered perfect, and were as a rule only used for shakes, especially on the continent. They were little used in France when Devienne published his celebrated Methode (1795). Although Hugot and Wunderlich recommend them in their Tutor of 1801 (where, by the way, the low C♮ and C♯ keys are condemned), they were not generally adopted till the beginning of the nineteenth century. AsTromlitz scornfully remarked of his contemporaries, they only "used the fingering of one hundred years ago because it was used by their grandfathers." To Johann George Tromlitz (c. 1730-1805), a Leipsic flautist, is to be ascribed the invention (before 1786) of the long F♮ key, used on all modern eight-keyed flutes. This key is not much used in playing, and was objected to by Nicholson, who would not have it on his flute, and by Tulou, but was advocated by Drouet. Tromlitz's chief merit was that he attempted to make flutes on a rational principle, and that he aimed at perfect intonation throughout the entire compass of the instrument, being a strenuous advocate of an open-keyed system (Page 31, Fig. 3). He added another long key for B♭ (worked by the first finger of the right hand), altered the position of the G♯ hole and key, and made several other changes which may be disregarded as they were not permanently retained. Tromlitz published three important works on the flute in 1786, 1791, and 1800 respectively; in those of 1791 and 1800 he seems rather to disapprove of keys (save in the hands of skilled players), of the tuning slide, and the low C♮ and C♯ keys. In the book of 1800 he advocates a flute with only a D♯ key, but with holes for the thumbs (F♯, B♮), and for the little finger of the left hand (G♯). This is interesting as being the earliest attempt to produce a chromatic flute with open holes; but his system left many "veiled" notes; still it was a step in the right direction. ThisOpen

Keys idea of constructing a chromatic flute with all the holes open and in their true positions was carried still further by Dr. H. W. Pottgiesser between 1803-24. According to Ward, his was "the first truly scientific remodelling of the flute." Pottgiesser's first flute, in two pieces only and with only one key, was wider in bore and shorter than other flutes. In his second flute (with keys) he equalized the size of the finger-holes, suggested rollers for the "touches" of the thumb-keys, and introduced a perforated key for the C♯ hole. The object of this "ring and crescent" key was to alter the size of the C♯ hole, in order to render it better in tune when the B♮ is closed.[3]

Fig. 12.—Nolan's Ring-key.

and Nolan's

Keys practically impossible, and is a most useful key, now found on all good flutes. More important still, the Rev. Frederick Nolan, of Stratford, in Essex, an amateur flautist, in 1808 invented or adopted a new kind of open key—more especially for the G♯—worked by a lever which ended in a ring placed over the hole of the note below. (Fig. 12.) This was the earliest contrivance by means of which an uncovered hole and an open key over another hole could be closed by one finger, which is a leading feature of the modern open-keyed system, and has been very largely adopted on all Böhm flutes. The history and details of Böhm's flute, however, deserve a separate chapter.

- ↑ We have no evidence as to the exact pitch of these early flutes; but I have, for sake of clearness, assumed throughout that the lowest note was D, as in the ordinary German flute of later years.

- ↑ We learn from Quantz that flutes in three pieces first appeared towards the end of the seventeenth century.

- ↑ For diagrams of Pottgeisser's first flute and his ring-and-crescent key, and also for portrait of Tromlitz, see English Music pp. 147-8.