The Story of the Flute/Chapter 7

CHAPTER VII.

THE PICCOLO: THE F FLUTE.

Piccolo—Orchestral use—Characteristics—Berlioz on its abuse—Its various registers—As used by great composers—Two piccolos—With cymbals, bells, etc.—As a solo instrument—Military varieties—The F flute.

The Flauto Piccolo, the highest pitched instrument of the orchestra, is a development of the earlier conicalThePiccolo

in the

Orchestra Schweitzerpfeiff, and to this day the conical bore is preferred to the cylinder bore, although some piccolos are made with the latter. The piccolo is in a sense a transposing instrument, as it sounds an octave above the written note. This is done in order to avoid numerous ledger lines. The compass of the instrument is said to extend to the C in altissimo,

The piccolo seems to have first appeared in the orchestra about 1700. Destouches and Lalande in The Elements (c. 1721) have two little flutes. Rameau used one in his overture AcantheIts Intro-

duction and Céphise (1751) and two in his Pigmalion (1748). Haydn uses it once (Spring), and Gluck introduces it in several of his operas. Beethoven was the first to introduce it into a symphony.

In the orchestra the piccolo is as a rule played by the second flute-player, unless when played along with both flutes. A question has been raised as to whether piccolo playing is injurious to the tone of a flute-player, the embouchure being so different. Certainly the great piccolo-players, such as Frisch (c. 1840), Harrington Young, Le Thière, Roe, etc., did not shine very preeminently as flute-players. The French excel as piccoloists.

The piccolo is the noisiest and least refined in tone of the whole orchestra, and is apt to give a tinge of vulgarity if injudiciously introduced—as it too often is. It is, in fact, in all respectsIts Char-

acteristics;

Use, and

Abuse the most abused instrument: abused by composers, players, and audiences alike. Berlioz says: "When I hear this instrument employed in doubling in triple octave the air of a baritone, or casting its squeaking voice into the midst of a religious harmony, or strengthening or sharpening (for the sake of noise only) the high part of an orchestra from beginning to end of an act of an opera, I cannot help feeling that this mode of instrumentation is one of platitudes and stupidity. The piccolo may, however, have a very happy effect in soft passages, and it is a mere prejudice to think that it should only be played loud." Examples of most effective use of the piccolo pianissimo will be found in Beethoven's Turkish March in the Ruins of Athens, and in Schumann's Faust (ii. 5), where it is so used on its highest register. It absolutely lacks the poetic sweetness of the flute. The lower notes are feeble, dull, and devoid of any particular character; the middle register is the best, whilst the upper notes are harsh and piercing, the very top ones being almost unbearably so. There is very little real musical tone to be got out of the instrument—it is, in fact, nothing but a glorified tin-whistle. Nevertheless, it has its uses: an occasional sudden flash on the piccolo is very thrilling, and it can create certain piquant effects and accentuate brilliant points in the score better than any other member of the orchestra.

The chief vocation of the piccolo is to reproduce the noises of the elements of nature, the strident howling of the tempest, the flash of the lightning, the torrent of the rain. There is something diabolic and mocking in its upper notes; hence it has been employed by many dramatic composers to typify infernal revelry and satanic orgies. Marschner uses two piccolos in his Le Vampire and Gounod and Berlioz both introduce it along with Mephistopheles in their respective Fausts. So, too, Sullivan, in The Golden Legend heralds the approach of Lucifer by a lightning flash on the piccolo. It is clearly a diabolical instrument—often in more senses than one!

Weber, Wagner, and Sullivan have used the piccolo in scenes of magic and the supernatural with striking effect. Wagner several times portrays the rustling of leaves and of trees by means of it.

Owing to its bright, gay character, the piccolo is also much used in joyous pastoral scenes, village fêtes, and dances. Verdi uses it to produce comic effects in his Falstaff. It is very rarely used in sacred music:

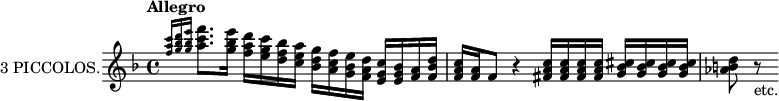

Bizet, Carman, i. 3, March.

![\new Staff = "piccolos" \with {

instrumentName = \markup \center-column {

"2 PICCOLOS ONLY.:"

"at first alone then"

"with Strings pizz."

}

midiInstrument = "piccolo"

} <<

\new Voice = "first" \relative c'' {

\transposition c' \voiceOne

\key f \major

\time 2/4

\tempo "Allegro"

\tweak text "bis. ten."

\startMeasureSpanner

\autoBeamOff

\acciaccatura cis'8\ppp d[ a a d]

\autoBeamOn

cis b b4\f

\stopMeasureSpanner

c!( d8) c

d c16 d e8 e,

cis'4\trill \acciaccatura {b16 cis} d8\staccato d\staccato

a a d, r

}

\new Voice = "second" \relative c'' {

\transposition c' \voiceTwo

\key f \major

\time 2/4

\tempo "Allegro"

\tweak text "bis. ten."

\startMeasureSpanner

\autoBeamOff

\acciaccatura cis8 d[ f f d]

\autoBeamOn

e g f4

\stopMeasureSpanner

bes!8( a16 g a8) c

\autoBeamOff

bes[ a gis e]

\autoBeamOn

g!4( f8) d

a a d r \bar "|."

}

>>

\layout {

indent = 4\cm

\context {

\Staff

\consists Measure_spanner_engraver

}

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/m/8mbr6piy6oufelmfrxalsow6j4nja3o/8mbr6piy.png)

Cherubini introduces it into his Coronation Mass in A, Berlioz uses it in his L'Enfance du Christ and Te Deum, and Brahm in his Requiem as does also Dvôràk. In Massenet's Scenes Pittoresques the lower notes are used effectively in the slow, quiet "Angelus."

In the orchestra the piccolo is often very useful to continue an ascending passage above the compass of the flute, and to brighten the tone. Its sharp, accentuated rhythm is very useful in martial scenes, as in Bizet's Carmen. Auber uses the instrument with great skill.

Though usually played along with the flute in orchestral works, the piccolo is often used alone veryTwo

Piccolos effectively. Two piccolos are occasionally used, either in addition to the flutes or without them. Spohr has a passage in his overture Jessonda for two piccolos in F without flutes. Berlioz, in his Faust ("Evocation"), uses three piccolos (without flutes), playing separate parts. This is the only instance I know of three being used. I don't think any composer has introduced four separate parts for

Berlioz, Faust, "Evocation."

piccolos in any orchestral work. Spontini (Nourmahal) was apparently the first to discover the combinationWith

Cymbals,

ect. of the piccolo with the cymbals. "It cuts and rends instantaneously like the stab of a poignard," says Berlioz. Modern composers have frequently used it along with the cymbals, bells, triangle, or glockenspiel; Saint-Saens produces a ghastly effect in his Danse Macabre by combining it with the xylophone.

Owing to its great agility, the piccolo is frequently used as a solo instrument, chiefly to imitate birds or for squealing variations. These sparkling (but utterly trivial) compositions are usually in the polka or waltz form, and Bousquet, Donjon, and othersAs Solo

Instrument have written several pieces of this kind for two piccolos. But such things are only tolerable in a very large hall or in the open air, where they are often performed by military bands. A piccolo solo in the drawing-room is not to be tolerated save by those who are stone-deaf.

In military bands various other sizes of piccolo are used. The French use one in D♭, a minor 9th higher than the concert flute, whilst the Italians preferMilitary

Varieties one in E♭.[1] These are practically never used in orchestra, the only instances of which I am aware being Schumann's Paradise and the Peri, Berlioz's Symphonie Funebre (as originally written for a military band), and Spohr's overture The Fall of Babylon; in all of which the D♭ piccolo is used.

Numerous other varieties of small flutes have from time to time been devised. One in E♭ is specially adapted for military bands; their musicThe F

Flute being usually written in flat keys. The only variety ever found in orchestral works is the F flute, sometimes called the Tierce, or Third Flute, as it sounds a minor third above the concert flute. It is less piercing than the piccolo, and has more vigour than the C flute. It is introduced by Mozart in the original score of L'Enlevement au Serail, by Spohr in his Power of Sound symphony—in addition to an ordinary flute—and by Gade in the Siren's song in The Crusaders, probably to avoid the difficulty of the key on the ordinary flute. Bishop originally wrote the obligato to his famous song, "Lo, hear the Gentle Lark," for an F flute.

- ↑ Jullien in his Zouave's Band (1856) had one piccolo in F♯, one in D♭, one F flute and two concert flutes.