The Tragedy in Dartmoor Terrace

III.

THE TRAGEDY IN DARTMOOR TERRACE.

Being the Third Mystery Explained by the Remarkable Old Man in the Corner, who Appears to Delight in Tying Knots in String that no one Can Possibly Undo, whilst he Unravels Knotty Problems in Crime that no one else Can Unravel. In this Story he Clears up the Weird Circumstances Connected with the Death of Mrs. Yule.

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ.

The Old Man in the Corner . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Who Unravels the Mystery to— |

The Lady Journalist . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Who Re-tells it to the Royal Readers. |

Mrs. Yule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

A rich Widow who is found dead in her house. |

William Yule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Her Son. |

Mrs. William Yule . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

His Wife. |

William Bloggs . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

A gardener's Son whom Mrs. Yule adopted. |

Mr. Statham . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

A Solicitor. |

Annie and Jane . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . |

Servants |

CHAPTER I.

"It is not by any means the Law and Police Courts that form the only interesting reading in the daily papers," said the man in the corner airily, as he munched his eternal bit of cheesecake and sipped his glass of milk, like a frowsy old tom cat.

"You don't agree with me," he added, for I had offered no comment to his obvious remark.

"No?" I answered. "I suppose you were thinking———"

"Of the tragic death of Mrs. Yule, for instance," he replied eagerly. "Beyond the inquest, and its very unsatisfactory verdict, very few circumstances connected with that interesting case ever got into the papers at all."

"I forget what the verdict actually was," I said, eager, too, on my side to hear him talk about that mysterious tragedy, which, as a matter of fact, had puzzled a good many people.

"Oh, it was as vague and as wordy as the English language would allow. The jury found that 'Mrs. Yule had died through falling downstairs, in consequence of a fainting attack, but how she came to fall is not clearly shown.'"

"What had happened was this: Mrs. Yule was a rich and eccentric old lady, who lived very quietly in a small house in Kensington; No. 9, Dartmoor Terrace is, I believe, the correct address.

"She had no expensive tastes, for she lived, as I said before, very simply and quietly in a small Kensington house, with two female servants—a cook and a housemaid—and a young fellow whom she had adopted as her son.

"The story of this adoption is, of course, the pivot round which all the circumstances of the mysterious tragedy revolved. Mrs. Yule, namely, had an only son, William, to whom she was passionately attached; but, like many a fond mother, she had the desire of mapping out that son's future entirely according to her own ideas. William Yule, on the other hand, had his own views with regard to his own happiness, and one fine day went so far as to marry the girl of his choice, and that in direct opposition to his mother's wishes.

"Mrs. Yule's chagrin and horror at what she called her son's base ingratitude knew no bounds; at first it was even thought that she would never get over it.

"'He has gone in direct opposition to my fondest wishes, and chosen a wife whom I could never accept as a daughter; he shall have none of the property which has enriched me, and which I know he covets.'

"At first her friends imagined that she meant to leave all her money to charitable institutions; but oh! dear me, no! Mrs. Yule was one of those women who never did anything that other people expected her to. Within three years of her son's marriage she had filled up the place which he had vacated, both in her house and in her heart. She had adopted a son, preferring, as she said, that her money should benefit an individual rather than an institution.

"Her choice had fallen upon the only son of a poor man—an ex-soldier—who used to come twice a week to Dartmoor Terrace to tidy up the small garden at the back: he was very respectable and very honest—was born in the same part of England as Mrs. Yule, and had an only son whose name happened to be William: he rejoiced in the surname of Bloggs.

"'It suits me in every way,' explained Mrs. Yule to old Mr. Statham, her friend and solicitor. 'You see, I am used to the name of William, and the boy is nice-looking and has done very well at the Board School. Moreover, old Bloggs will die within a year or two, and William will be left without any incumbrances.'

"Herein Mrs. Yule's prophecy proved to be correct. Old Bloggs did die very soon, and his son was duly adopted by the rich and eccentric old lady, sent to a good school, and finally given a berth in the Union Bank.

"I saw young Bloggs—it is not a euphonious name, is it?—at that memorable inquest later on. He was very young and unassuming, and used to keep very much out of the way of Mrs. Yule's friends, who, mind you, strongly disapproved of his presence in the rich old widow's house, to the detriment of the only legitimate son and heir.

"What happened within the intimate and close circle of 9, Dartmoor Terrace during the next three years of course nobody can tell. Certain it is that by the time young Bloggs was nearing his twenty-first birthday, he had become the very apple of his adopted mother's eye.

"During those three years Mr. Statham and other old friends had worked hard in the interests of William Yule. Everyone felt that the latter was being very badly treated indeed. He had studied painting in his younger days, and now had set up a small studio in Hampstead, and was making perhaps a couple of hundred or so a year, and that, with much difficulty, whilst the gardener's son had supplanted him in his mother's affections, and, worse still, in his mother's purse.

"The old lady was more obdurate than ever. In deference to the strong feelings of her friends she had agreed to see her son occasionally, and William Yule would call upon his mother from time to time—in the middle of the day when Bloggs was out of the way at the Bank—stay to tea, and part from her in frigid, though otherwise amicable, terms.

"'I have no ill-feeling against my son,' the old lady would say, 'but when he married against my wishes, he became a stranger to me—that is all—a stranger, however, whose pleasant acquaintanceship I am pleased to keep up.'

"That the old lady meant to carry her eccentricities in this respect to the bitter end, became all the more evident, when she sent for her old friend and lawyer, Mr. Statham, and explained to him that she wished to make over to young Bloggs the whole of her property by deed of gift, during her lifetime—on condition that on his twenty-first birthday he legally took up the name of Yule.

"Mr. Statham subsequently made public, as you know, the whole of this interview which he had with Mrs. Yule.

The old lady was found dead at the foot of the stairs.

"'I tried to dissuade her, of course,' he said, 'for I thought it so terribly unfair on William Yule, and his children. Moreover, I had always hoped that when Mrs. Yule grew older and more feeble she would surely relent towards her only son. But she was terribly obstinate.'

"'It is because I may become weak in my dotage,' she said, 'that I want to make the whole thing absolutely final—I don't want to relent. I wish that William should suffer, where I think he will suffer most, for he was always over fond of money. If I make a will in favour of Bloggs, who knows I might repent it, and alter it at the eleventh hour? One is apt to become maudlin when one is dying, and has people weeping all round one. No!—I want the whole thing to be absolutely irrevocable; and I shall present the deed of gift to young Bloggs on his twenty-first birthday. I can always make it a condition that he keeps me in moderate comfort to the end of my days. He is too big a fool to be really ungrateful, and after all I don't think I should very much mind ending my life in the workhouse.'

"'What could I do?' added Mr. Statham. 'If I had refused to draw up that iniquitous deed of gift, she only would have employed some other lawyer to do it for her. As it is, I secured an annuity of £500 year for the old lady, in consideration of a gift worth some £30,000 made over absolutely to Mr. William Bloggs.'

"The deed was drawn up," continued the man in the corner, "there is no doubt of that. Mr. Statham saw to it. The old lady even insisted on having two more legal opinions upon it, lest there should be the slightest flaw that might render the deed invalid. Moreover, she caused herself to be examined by two specialists in order that they might testify that she was absolutely sound in mind, and in full possession of all her faculties.

"When the deed was all that the law could wish, Mr. Statham handed it over to Mrs. Yule, who wished to keep it by her until April 3rd—young Bloggs' twenty-first birthday—on which day she meant to surprise him with it.

"Mr. Statham handed over the deed to Mrs. Yule on February 14th, and on March 28th—that is to say, six days before Bloggs' majority—the old lady was found dead at the foot of the stairs in Dartmoor Terrace, whilst her desk was found to have been broken open, and the deed of gift had disappeared."

CHAPTER II.

"From the very first the public took a great interest in the sad death of Mrs. Yule. The old lady's eccentricities were pretty well known throughout all her neighbourhood, at any rate. Then, she had a large circle of friends, who all took sides, either for the disowned son or for the old lady's rigid and staunch principles of filial obedience.

"Directly, therefore, that the papers mentioned the sudden death of Mrs. Yule, tongues began to wag, and whilst some asserted 'Accident,' others had already begun to whisper 'Murder.'

"For the moment nothing definite was known. Mr. Bloggs had sent for Mr. Statham, and the most persevering and most inquisitive persons of both sexes could glean no information from the cautious old lawyer.

"The inquest was to be held on the following day, and perforce curiosity had to be bridled until then. But you may imagine how that coroner's court at Kensington was packed on that day. I, of course, was at my usual place—well to the front—for I was already keenly interested in the tragedy, and knew that a palpitating mystery lurked behind the old lady's death.

"Annie, the housemaid at Dartmoor Terrace, was the first, and I may say the only really important, witness during that interesting inquest. The story she told amounted to this: Mrs. Yule, it appears, was very religious, and, in spite of her advancing years and decided weakness of the heart, was in the habit of going to early morning service every day of her life at six o'clock. She would get up before anyone else in the house, and winter or summer, rain, snow, or fine, she would walk round to St. Matthias' Church, coming home at about a quarter to seven, just when her servants were getting up.

"On this sad morning (March 28th) Annie explained that she got up as usual and went downstairs (the servants slept at the top of the house) at seven o'clock. She noticed nothing wrong, her mistress's bedroom door was open as usual, Annie merely remarking to herself that the mistress was later than usual from church that morning. Then suddenly, in the hall at the foot of the stairs, she caught sight of Mrs. Yule lying head downwards, her head on the mat, motionless.

"'I ran downstairs as quickly as I could,' continued Annie, 'and I suppose I must 'ave screamed, for cook came out of 'er room upstairs, and Mr. Bloggs, too, shouted down to know what was the matter. At first we only thought Mrs. Yule was unconscious like. Me and Mr. Bloggs carried 'er to 'er room, and then Mr. Bloggs ran for the doctor.'

"The rest of Annie's story," continued the man in the corner, "was drowned in a deluge of tears. As for the doctor, he could add but little to what the public had already known and guessed. Mrs. Yule undoubtedly suffered from a weak heart, although she had never been known to faint. In this instance, however, she undoubtedly must have turned giddy, as she was about to go downstairs, and fallen headlong. She was of course very much injured—the doctor explained—but she actually died of heart failure, brought on by the shock of the fall. She must have been on her way to church, for her prayer book was found on the floor close by her, also a candle—which she must have carried, as it was a dark morning—had rolled along and extinguished itself as it rolled. From these facts, therefore, it was gathered that the poor old lady came by this tragic death at about six o'clock, the hour at which she regularly started out for morning service. Both the servants and also Mr. Bloggs slept at the top of the house, and it is a known fact that sleep in most cases is always heaviest in the early morning hours; there was, therefore, nothing strange in the fact that no one heard either the fall or a scream, if Mrs. Yule uttered one, which is doubtful.

"So far you see," continued the man in the corner, after a slight pause, "there did not appear to be anything very out of the way or mysterious about Mrs. Yule's tragic death. But the public had expected interesting developments, and I must say their expectations were more than fully realised.

"Jane, the cook, was the first witness to give the public an inkling of the sensations to come.

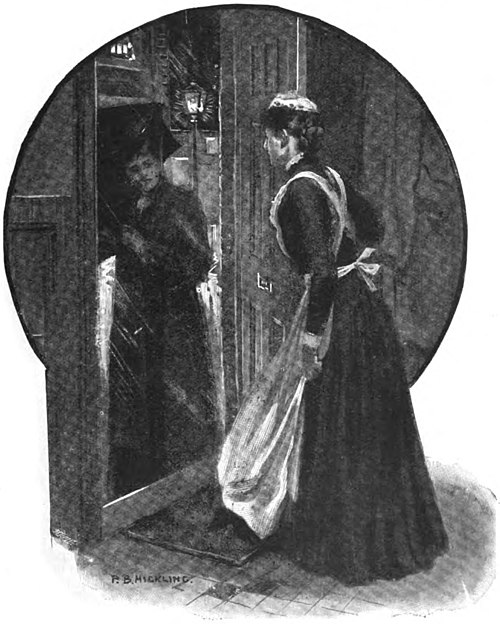

"She deposed that on Thursday, the 27th, she was alone in the kitchen in the evening after dinner, as it was the housemaid's evening out, when, at about nine o'clock there was a ring at the bell.

"'I went to answer the door,' said Jane, 'and there was a lady, all dressed in black as far as I could see—as the 'all gas always did burn very badly—still I think she was dressed dark, and she 'ad on a big 'at and a veil with spots. She says to me: "Mrs. Yule lives 'ere?" I says "She do 'm," though I don't think she was quite the lady, so I don't know why I said 'm, but———'

"'Yes, yes!' here interrupted the coroner somewhat impatiently, 'it doesn't matter what you said. Tell us what happened.'

"'Yes, sir.' continued Jane, quite undisturbed, 'as I was saying, I asked the lady her name, and she says: "Tell Mrs. Yule I would wish to speak with her," then as she saw me 'esitating, for I didn't like leaving 'er all alone in the 'all, she said, "Tell Mrs. Yule, that Mrs. William Yule wishes to speak with 'er."

"'I went to answer the door,' said Jane, 'and there was a lady all dressed in black . . . . and she 'ad on a big 'at and a veil with spots.'

"Jane paused to take breath, for she talked fast and volubly, and all eyes were turned to a corner of the room, where William Yule, dressed in the careless fashion affected by artists, sat watching and listening eagerly to everything that was going on. At the mention of his wife's name he shrugged his shoulders, and I thought for the moment that he would jump up and say something; but he evidently thought better of it, and remained as before, silent and quietly watching.

"'You showed the lady upstairs?' asked the coroner, after an instant's most dramatic pause.

"'Yes, sir,' replied Jane; 'but I went to ask the mistress first. Mrs. Yule was sitting in the drawing-room reading. She says to me, "Show the lady up at once; and, Jane," she says, "ask Mr. Bloggs to kindly come to the drawing-room." I showed the lady up, and I told Mr. Bloggs, who was smoking in the library, and 'e went to the drawing-room.

"'When Annie come in,' continued Jane, with increased volubility, 'I told 'er 'oo 'ad come, and she and me was very astonished, because we 'ad often seen Mr. William Yule come to see 'is mother, but we 'ad never seen 'is wife. "Did you see what she was like, cook?" says Annie to me. "No," I says, "the 'all gas was burnin' that badly, and she 'ad a veil on." Then Annie ups and says, "I must go up, cook," she says, "for my things is all wet. I never did see such rain in all my life. I tell you my boots and petticoats is all soaked through." Then up she runs, and I thought then that per'aps she meant to see if she couldn't 'ear anything that was goin' on upstairs. Presently she come down———'

"But at this point Jane's flow of eloquence received an unexpected check. The coroner preferred to hear from Annie herself whatever the latter may have overheard, and Jane, very wrathful and indignant, had to stand aside, while Annie, who was then recalled, completed the story.

"'I don't know what made me stop on the landing,' she explained timidly, 'and I'm sure I didn't mean to listen. I was going upstairs to change my things, and put on my cap and apron, in case the mistress wanted anything.

"'Then, I don't think I ever 'eard Mrs. Yule's voice so loud and angry.'

"'You stopped to listen?' asked the coroner.

"'I couldn't 'elp it, sir. Mrs. Yule was shoutin' at the top of 'er voice. "Out of my house," she says, "I never wish to see you or your precious husband inside my doors again."'

"'You are quite sure that you heard those very words?' asked the coroner earnestly.

"'I'll take my Bible oath on every one of them, sir,' said Annie emphatically. 'Then I could 'ear someone crying and moaning: "Oh! what have I done? Oh! what have I done?" I didn't like to stand on the landing then, for fear someone should come out, so I ran upstairs, and put on my cap and apron, for I was all in a tremble, what with what I'd 'eard, and the storm outside, which was coming down terrible.

"'When I went down again, I 'ardly durst stand on the landing, but the door of the drawing-room was ajar, and I 'eard Mr. Bloggs say: "Surely you will not turn a human being, much less a woman, out on a night like this?" And the mistress said, still speaking very angry: "Very well, you may sleep here; but remember, I don't wish to see your face again. I go to church at six and come home again at seven; mind you are out of the house before then. There are plenty of trains after seven o'clock.'"

"After that," continued the man in the corner, "Mrs. Yule rang for the housemaid and gave orders that the spare-room should be got ready, and that the visitor should have some tea and toast brought to her in the morning as soon as Annie was up.

"But Annie was rather late on that eventful morning of the 28th. She did not go downstairs till seven o'clock. When she did, she found her mistress lying dead at the foot of the stairs. It was not until after the doctor had been and gone that both the servants suddenly recollected the guest in the spare-room. Annie knocked at her door, and, receiving no answer, she walked in; the bed had not been slept in, and the spare-room was empty.

"'There, now!' was the housemaid's decisive comment, 'me and cook did 'ear some one cross the 'all, and the front door bang about an hour after every one else was in bed.'

"Presumably, therefore, Mrs. William Yule had braved the elements and left the house at about midnight, leaving no trace behind her, save, perhaps, the broken lock of the desk that had held the deed of gift in favour of young Bloggs."

CHAPTER III.

"Some say there's a Providence that watches over us," said the man in the corner, when he had looked at me keenly, and assured himself that I was really interested in his narrative, "others use the less poetic and more direct formula, that 'the devil takes care of his own.' The impression of the general public during this interesting coroner's inquest was that the devil was taking special care of his own—('his own' being in this instance represented by Mrs. William Yule, who, by the way, was not present).

"What the Evil One had done for her was this: He caused the hall gas to burn so badly on that eventful Thursday night, March 27th, that Jane, the cook, had not been able to see Mrs. William Yule at all distinctly. He, moreover, decreed that when Annie went into the drawing-room later on to take her mistress's orders, with regard to the spare room, Mrs. William was apparently dissolved in tears, for she only presented the back of her head to the inquisitive glances of the young housemaid.

"After that the two servants went to bed, and heard someone cross the hall and leave the house about an hour or so later; but neither of them could swear positively that they would recognise the mysterious visitor if they set eyes on her again.

"Throughout all these proceedings, however, you may be sure that Mr. William Yule did not remain a passive spectator. In fact, I, who watched him, could see quite clearly that he had the greatest possible difficulty in controlling himself. Mind you, I knew by then exactly where the hitch lay, and I could, and will presently, tell you exactly all that occurred on Thursday evening, March 27th, at No. 9, Dartmoor Terrace, just as if I had spent that memorable night there myself; and I can

William Yule . . . had with one bound reached the witness-box, and struck young Bloggs a violent blow in the face.

assure you that it gave me great pleasure to watch the faces of the two men most interested in the verdict of this coroner's jury.

"Everyone's sympathy had by now entirely veered round to young Bloggs, who for years had been brought up to expect a fortune, and had then, at the last moment, been defrauded of it, through what looked already much like a crime. The deed of gift had, of course, not been what the lawyers call 'completed.' It had rested in Mrs. Yule's desk, and had never been 'delivered' by the donor to the donee, or even to another person on his behalf.

"Young Bloggs, therefore, saw himself suddenly destined to live his life as penniless as he had been when he was still the old gardener's son.

"No doubt the public felt that what lurked mostly in his mind was a desire for revenge, and I think everyone forgave him when he gave his evidence with a distinct tone of animosity against the woman, who had apparently succeeded in robbing him of a fortune.

"He had only met Mrs. William Yule once before, he explained, but he was ready to swear that it was she who called that night. As for the original motive of the quarrel between the two ladies, young Bloggs was inclined to think that it was mostly on the question of money.

"'Mrs. William,' continued the young man, 'made certain peremptory demands on Mrs. Yule, which the old lady bitterly resented.'

"But here there was an awful and sudden interruption. William Yule, now quite beside himself with rage, had with one bound reached the witness-box, and struck young Bloggs a violent blow in the face.

"'Liar and cheat!' he roared, 'take that!'

"And he prepared to deal the young man another even more vigorous blow, when he was overpowered and seized by the constables. Young Bloggs had become positively livid; his face looked grey and ashen, except there, where his powerful assailant's fist had left a deep purple mark.

"'You have done your wife's cause no good,' remarked the coroner drily, as William Yule, sullen and defiant, was forcibly dragged back to his place. 'I shall adjourn the inquest until Monday, and will expect Mrs. Yule to be present and to explain exactly what happened after her quarrel with the deceased, and why she left the house so suddenly and mysteriously that night.'

"William Yule tried an explanation even then. His wife had never left the studio in Sheriff Road, West Hampstead, the whole of that Thursday evening. It was a fearfully stormy night, and she never went outside the door. But the Yules kept no servant at the cheap little rooms; a charwoman used to come in every morning only for an hour or two, to do the rough work; there was no one, therefore, except the husband himself to prove Mrs. William Yule's alibi.

"At the adjourned inquest, on the Monday, Mrs. William Yule duly appeared; she was a young, delicate-looking woman, with a patient and suffering face, that had not an atom of determination or vice in it.

"Her evidence was very simple; she merely swore solemnly that she had spent the whole evening indoors, she had never been to 9, Dartmoor Terrace in her life, and, as a matter of fact, would never have dared to call on her irreconcilable mother-in-law. Neither she nor her husband were specially in want of money either.

"'My husband had just sold a picture at the Water Colour Institute,' she explained, 'we were not hard up; and certainly I should never have attempted to make the slightest demand on Mrs. Yule.'

"There the matter had to rest with regard to the theft of the document, for that was no business of the coroner's or of the jury. According to medical evidence the old lady's death had been due to a very natural and possible accident—a sudden feeling of giddiness—and the verdict had to be in accordance with this.

"There was no real proof against Mrs. William Yule—only one man's word, that of young Bloggs; and it would no doubt always have been felt that his evidence might not be wholly unbiased. He was therefore well advised not to prosecute. The world was quite content to believe that the Yules had planned and executed the theft, but he never would have got a conviction against Mrs. William Yule just on his own evidence.

[At this point you should try to puzzle out the mystery for yourselves.—Ed.]

CHAPTER IV.

"Then William Yule and his wife were left in full possession of their fortune?" I asked eagerly.

"Yes, they were," he replied; "but they had to go and travel abroad for a while; feeling was so high against them. The deed, of course, not having been 'delivered,' could not be upheld in a court of law; that was the opinion of several eminent counsel whom Mr. Statham, with a lofty sense of justice, consulted on behalf of young Bloggs."

"And young Bloggs was left penniless?"

"No," said the man in the corner, as, with a weird and satisfied smile, he pulled a piece of string out of his pocket; "the friends of the late Mrs. Yule subscribed the sum of £1000 for him, for they all thought he had been so terribly badly treated, and Mr. Statham has taken him in his office as articled pupil. No! no! young Bloggs has not done so badly either———"

"What seems strange to me," I remarked, "is that, for ought she knew, Mrs. William Yule might have committed only a silly and purposeless theft. If Mrs. Yule had not died suddenly and accidentally the next morning, she would, no doubt, have executed a fresh deed of gift, and all would have been in statu quo."

"Exactly," he replied drily, whilst his fingers fidgeted nervously with his bit of string.

"Of course," I suggested, for I felt that the funny creature wanted to be drawn out; "she may have reckoned on the old lady's weak heart, and the shock to her generally, but it was, after all, very problematical."

"Very," he said, "and surely you are not still under the impression that Mrs. Yule's death was purely the result of an accident?"

"What else could it be?" I urged.

"The result of a slight push from the top of the stairs," he remarked placidly, whilst a complicated knot went to join a row of its fellows.

"But Mrs. William Yule had left the house before midnight—or, at any rate, someone had. Do you think she had an accomplice?"

"I think," he said excitedly, "that the mysterious visitor who left the house that night had an instigator whose name was William Bloggs."

"I don't understand," I gasped in amazement.

"Point No. 1," he shrieked, while the row of knots followed each other in rapid succession, 'young Bloggs swore a lie when he swore that it was Mrs. William Yule who called at Dartmoor Terrace that night."

"What makes you say that?" I retorted.

"One very simple fact," he replied, "so simple that it was, of course, overlooked. Do you remember that one of the things which Annie overheard was old Mrs. Yule's irate words, 'Very well, you may sleep here; but, remember, I do not wish to see your face again. You can leave my house before I return from church; you can get plenty of trains after seven o'clock.' Now what do you make of that?" he added triumphantly.

"Nothing in particular," I rejoined; "it was an awfully wet night, and———"

"And High Street Kensington Station within two minutes' walk of Dartmoor Terrace, with plenty of trains to West Hampstead, and Sheriff Road within two minutes of this latter station," he shrieked, getting more and more excited, "and the hour only about ten o'clock, when there are plenty of trains, from one part of London to another? Old Mrs. Yule, with her irascible temper, and obstinate ways would have said: 'There's the station, not two minutes' walk, get out of my house, and don't ever let me see your face again.' Wouldn't she now?"

"It certainly seems more likely."

"Of course it does. She only allowed the woman to stay because the woman had either a very long way to go to get a train, or perhaps had missed her last train—a connection on a branch line presumably—and could not possibly get home at all that night."

"Yes, that sounds logical," I admitted.

"Point No. 2," he shrieked, "young Bloggs having told a lie, had some object in telling it. That was my starting point; from there I worked steadily until I had reconstructed the events of that Thursday night—nay more, until I knew something more about young Bloggs' immediate future, in order that I might then imagine his past.

"And this is what I found.

"After the tragic death of Mrs. Yule, young Bloggs went abroad at the expense of some kind friends, and came home with a wife, whom he is supposed to have met and married in Switzerland. From that point everything became clear to me. Young Bloggs had told a lie when he swore that it was Mrs. William Yule who called that night—it was certainly not Mrs. William Yule; therefore it was somebody who either represented herself as such, or who believed herself to be Mrs. William Yule.

"The first supposition," continued the funny creature, "I soon dismissed as impossible; young Bloggs knew Mrs. William Yule by sight—and since he had lied, he had done so deliberately. Therefore to my mind the lady who called herself Mrs. William Yule did so because she believed that she had a right to that name: that she had married a man, who, for purposes of his own had chosen to call himself by that name. From this point to that of guessing who that man was was simple enough."

"Do you mean young Bloggs himself?" I asked in amazement.

"And whom else?" he replied. "Isn't that sort of thing done every day? Bloggs was a hideous name, and Yule was eventually to be his own. With William Yule's example before him, he must have known that it would be dangerous to broach the marriage question at all before the old lady, and probably only meant to wait for a favourable opportunity of doing so. But after a while the young wife would naturally become troubled and anxious, and, like most women under the same circumstances, would become jealous and inquisitive as well.

"She soon found out where he lived, and no doubt called there thinking that old Mrs. Yule was her husband's own fond mother.

"You can picture the rest. Mrs. Yule, furious at having been deceived, herself destroys the deed of gift which she meant to present to her adopted son, and from that hour young Bloggs sees himself penniless.

"The false Mrs. Yule left the house, and young Bloggs waited for his opportunity on the dark landing of a small London house. One push and the deed was done. With her weak heart, Mrs. Yule was sure to die of the shock if not of the fall.

"Before that, already the desk had been broken open and every appearance of a theft given to it. After the tragedy, then, young Bloggs retired quietly to his room. The whole thing looked so like an accident that, even had the servants heard the fall at once, there would still have been time enough for the young villain to sneak into his room, and then to re-appear at his door, as if he, too, had been just awakened by the noise.

"The result turned out just as he expected. The William Yules have been and still are suspected of the theft; and young Bloggs is a hero of romance, with whom everyone is in sympathy."

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1943, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 81 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse