The Zoologist/4th series, vol 2 (1898)/Issue 688/Editorial Gleanings

EDITORIAL GLEANINGS.

We have received the Report of the South African Museum for 1897. The principal event was the opening of the new museum building on April 6th, the old building having been closed to the public on January 19th. The number of additions to the collection is very satisfactory, as the following details prove:—

The Director, Mr. W.L. Sclater, reports:—"The general state of the collections is satisfactory. The new cases are completely dust-proof, and, as far as can be seen at present, seem to be quite insect proof; any incipient attacks of museum pests can be easily dealt with by the introduction of a saucer of carbon bisulphide into the case, the fumes of which at once destroy any living matter."

In Mr. L. Péringuey's report on the Department of Entomology we read:—"The most interesting discoveries of the year have been the existence of a representative of the curious family Embiidæ of the order Neuroptera (gen.? Oligotoma) not before recorded in South Africa; and the curious parallelism of some coleopterous forms inhabiting the Cape and the Canary Islands, as exemplified by captures made by Mons. A. Raffray in the immediate vicinity of Cape Town. He has lately discovered a species of Metophthalmus (family Lathrididæ), three species of which are represented in the Canary Islands; he has also discovered an eyeless species of weevil (nov. gen.) and another (gen.? Pentatemenus), the eyes of which have only six facets. These insects belonging to the subfamily Cossoninae are very closely allied to similar ones occurring in the Canary Islands, and which are also found in the extreme South of Europe. Wollaston, as far back as 1861, described a Colydid (gen. Cossyphodes) from the Cape belonging to a genus known at the time as occurring only at Madeira. Another species was later on discovered in Abyssinia. It is a singular coincidence that both Cossyphodes and Metophthalmus should be discovered in such opposite directions. The true explanation is that the minute insects of Africa have not yet been properly collected, and that the genera mentioned above will be found to have a larger area of distribution than at first imagined."

Another very interesting record is found in Mr. Gilchrist's report on Marine Invertebrates:—"The specimen identified as Astacus capensis is of special interest, particularly as it is the only known representative of the European Lobster in South Africa. It is described by Herbst as being found in the rivers of the Colony, and as having all five pairs of legs chelate. The specimen procured was, however, found in a salt-water rock pool (at Sea Point), and others in the museum collection are described as from Algoa Bay. Moreover, all the legs are not chelate in these specimens. These points will receive special attention, as there is evidently an error somewhere."

The following extracts are taken from an article "By a South Sea Trader" in the 'Pall Mall Gazette' of July 12th:—

Twofold Bay, a magnificent deep-water harbour on the southern coast of New South Wales, is a fisherman's paradise, though its fame is but local, or known only to outsiders who may have spent a day there when travelling from Sydney to Tasmania in the fine steamers of the Union Company, which occasionally put in there to ship cattle from the little township of Eden. But the chief point of interest about Twofold Bay is that it is the rendezvous of the famous "Killers" (Orca gladiator), the deadly foes of the whole race of Cetaceans other than themselves, and the most extraordinary and sagacious creatures that inhabit the ocean's depths. From July to November two "schools" of Killers may be seen every day, either cruising to and fro across the entrance of the bay, or engaged in a Titanic combat with a Whale—a "Right" Whale, a "Humpback," or the long, swift "Finback." But they have never been known to tackle the great Sperm Whale, except when the great creature has been wounded by his human enemies. And to witness one of these mighty struggles is worth travelling many a thousand miles to see; it is terrible, awe-inspiring, and wonderful.

The Killer ranges in length from 10 ft. to 25 ft. (whalemen have told me that one was seen stranded on the Great Barrier Reef in 1862 which measured 37 ft.). They spout, "breach," and "sound" like other Cetaceans, and are of the same migratory habits as the two "schools" which haunt Twofold Bay, always leave there about November 28th to cruise in other seas, returning to their headquarters early in July, when the Humpback and Finback Whales make their appearance on the coast of New South Wales, travelling northwards to the breeding-grounds on the Brampton Shoals, the coast of New Guinea, and the Moluccas.

The whaling station at Twofold Bay is the only one in the Colony—the last remnant of a once great and thriving industry. It is carried on by a family named Davidson, father and sous, in conjunction with the Killers. And for more than twenty years this business partnership has existed between the humans and the Cetaceans, and the utmost rectitude and solicitude for each other's interests has always been maintained—Orca gladiator seizes the Whale for Davidson, and holds him until the deadly lance is plunged into his " life," and Davidson lets Orca carry the carcass to the bottom, and take his tithe of luscious blubber. This is the literal truth; and grizzled old Davidson or any one of the stalwart sons who man his two boats will tell you that but for the Killers, who do half of the work, whaling would not pay with oil only worth from £18 to £24 a tun.

When the men have done their part, comes the curious and yet absolutely truly described part that the Killers play in this ocean tragedy. The Killers, the moment the Whale is dead, close round him, and fastening their teeth into his body, bear him to the bottom. Here they tear out his tongue, and eat about one-third of his blubber. In about thirty-six to forty hours the carcass will rise again to the surface, and as the spot where he was taken down has been marked by a buoy, the boats are ready waiting to tow him ashore to the trying-out works. The Killers accompany the boats to the heads of the bay, and keep off the Sharks, which otherwise would strip off all the remaining blubber before the body had reached the shore.

The Killers never hurt a man. Time after time have boats been stove in or smashed into splinters by a Whale and the crew left struggling in the water to be rescued by the "pick-up" boat; and the Killers swim up to them, look at—ay, and smell them—but never touch them. And wherever the Killers are, the Sharks are not, for Jack Shark dreads a Killer as the devil dreads holy water. "Jack" will rush in and rip off a piece of blubber if he can, but he will watch his chance to do so.

Sometimes when a pack of Killers set out Whale-hunting they will be joined by a Thresher—the Fox Shark (Alopias vulpes), and then while the Killers bite and tear the unfortunate Cetacean, the Thresher deals him fearful blows with his scythe-like tail. The master of a whaling vessel told me that off the north end of New Caledonia there was a pack of nine Killers which were always attended by two Threshers and a Swordfish. Not only he but many other whaling skippers had seen this particular Swordfish year after year joining in attacks upon Whales. The cruising ground of this pack extended for thirty miles, and the nine creatures and their associates were individually known to hundreds of whalemen. And no doubt these combats, witnessed from a merchant ship, have led to many Sea Serpent stories; for when a Thresher stands his long twenty feet of slender body straight up on end like a pole, he presents a strange sight. But any American sperm-whaling captain will wink the other eye when you say "Sea Serpent."

Some Smelts have been caught in the Thames at Kew and Richmond. They were taken by anglers fishing with gentles for Roach and Dace. Last year Smelts worked as high up the Thames, and their presence there is of considerable interest, as it testifies to the increasing purity of the river.—Westminster Gazette, August 15th.

A society with the title of the Zoological Society of Edinburgh is being formed for the purpose of establishing a zoological garden. A public meeting was to be held early in October.

To protect the water-fowl and wild birds at Hampstead Heath some very pretty plantations have been made by the County Council near the ponds, and fenced in so as to keep the public from them. One result of this additional security is that there are now several broods of Cygnets, Wild Ducks, and Moorhens in the ponds. According to the keepers the wild fowl have trebled in number during the present year.

Mr. Lionel E. Adams has contributed "A Plea for Owls and Kestrels" in the 'Journ. Northamptonshire Nat. Hist. Soc.' for June last. The author rightly observes:—

The simple and direct test is the analysis of the "pellets" which these birds cast up. Many people (including a keeper that a friend of mine recently interviewed) are not aware that Owls, Hawks, and many other birds swallow their prey whole if small enough, or in lumps— fur, bones, feathers, everything together; and that after the flesh and nutritious juices have passed into the system, the indigestible bones, &c., are disgorged in masses usually known as "pellets." In Northamptonshire they are termed "quids," in Staffordshire, Derbyshire, and Cheshire "cuds," in Cambridgeshire "plugs," and in Lancashire and Cheshire they sometimes go by the suggestive name "boggart muck." This curious term doubtless originated from the fact that pellets are sometimes found in church towers and churchyards, and the mysterious hootings and screechings heard at night in these places give colour to 'the notion that "boggarts" (ghosts) are engaged upon their unhallowed feast!

These pellets contain, as stated, the bones of the animals preyed upon, usually in an almost perfect condition, the little skulls being perfectly easy to identify by a competent osteologist. It is still less generally known that many other birds eject similar pellets, e.g. the Swallow tribe, Herons, Gulls (and probably most sea-birds), Flycatchers, and Rooks. Rooks' pellets, by the way, may be found beneath the nests while the young are being fed, and never, I think, at other times, and I fancy they are composed of the indigestible portions of the food which the parent Rooks prepare for their young in a way similar to that peculiar to Pigeons.

I have carefully analysed and kept a record of many hundreds of Owls' pellets from or close to estates where game is reared, and from many parts of England and Ireland, at the time of year when Pheasants and Partridges are young and least able to take care of themselves; and I can positively assert that in no case have I ever found the remains of any game bird, chicken, or duckling. I once mentioned my experience to the late Lord Lilford, and that great authority informed me that his experience entirely tallied with mine.

It is impossible for us with due regard to our space to give the whole of Mr. Adams's statistics; the following are examples:—

If not molested, Owls will take up their abode near a farm and keep the Rats and Mice under much more effectively and cheaply than a professional Rat-catcher. Only last spring, close to a Derbyshire farm, I found within a fortnight fresh pellets containing:—Brown Rats, 82; Long-tailed Field Mice, 38; Common Shrews, 16; Short-tailed Field Mice, 5; Bank Voles, 10; Water Voles, 2; Frogs, 6; Toads, 2; Beetles, several: total, 141. And all this was due to (I think) a single pair of Long-eared Owls.

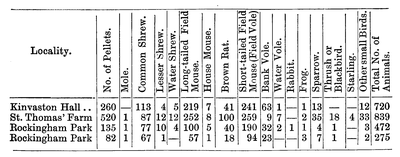

The first two of the following analyses are from pellets in old deserted Pigeon cotes in farm buildings near Stafford. In both cases the farmers protected and encouraged the birds. The third is from a nest in a hollow oak in Rockingham Park, Northants:—

The analysis of the Kestrels' pellets likewise determines its usual food, though, as these pellets are not found in quantities together, like those of Owls, but here and there sparingly, the same amount of certainty cannot be guaranteed. Most of those that have come under my personal notice have been composed entirely of the wing-cases of all sorts of beetles and the wings of flies, and sometimes the remains of a small Vole or Mouse, but I have never discovered the remains of birds or Rabbits. Indeed the bird is hardly large enough to attack the latter successfully, though a gamekeeper giving evidence before the Vole Plague Committee says:—"I have also seen one lift a young Rabbit." Whether "lift" is used in the Scotch sense of "carry off," or merely to "raise from the ground," does not appear; but the fact is unimportant in any case, and the Committee rightly came to the conclusion that "the food of this bird is known to consist almost exclusively of Mice, Grasshoppers, coleopterous insects and their larvæ."

Prof. Alexander Agassiz, after serving the Museum of Comparative Zoology at Cambridge, Massachusetts, for thirty-five years, has resigned his position as Director and Curator. Dr. W. McM. Woodworth has been appointed Assistant in charge of the Museum.—Athenæum.

The Society for the Biological Exploration of the Dutch Colonies has organized a scientific expedition to Java, which is to start next October under the direction of Dr. Max Weber, Professor of Zoology at Amsterdam. The object of the expedition, which is to last about a year, is the zoological, botanical, and oceanographical exploration of the seas of the Indian Archipelago.

Mr. F. G. Aflalo, writing to the 'Times' from Mevagissey, Cornwall (August), states:—

Sharks positively swarm just now in the 20-fathom water between Plymouth and the Land's End. I have been catching both the Blue and Por-beagle up to 40-lb. weight, and have lately had the former species round ray boat to a length of close on 5 ft., a dangerous size. I am, however, induced to publish this warning by the fact that on Wednesday a young fisherman of this place, dangling his hand over the side in manipulating his Mackerel lines, had the sleeve of his shirt torn to the elbow by one of these surface prowlers. Folk who acquire most of their knowledge of sea-fish in the metropolis are given to doubt the presence of true Sharks in the Channel, preferring to regard them as Dog-fish. May I give them my assurance, for what it is worth, that these are but two of several true British Sharks; that they are, as proved by the aforementioned episodes, both large and aggressive, and that they are most in evidence on those calm hot days that chiefly attract the bather.

Few zoologists are unfamiliar with the name of the publisher, John Van Voorst, who died on the 24th July, after a long and successful life, having been born as early as February 15th, 1804. He belonged to an ancient Dutch family which had settled in England several generations ago. He was apprenticed to Richard Nicholls, of Wakefield, somewhere about 1820, and, after passing some years with the Longmans, began business on his own account in 1835, in Paternoster Row. After publishing fine illustrated editions of such works as Gray's 'Elegy,' Goldsmith's 'Vicar of Wakefield,' &c, he turned his attention to the union of artistic execution with scientific publications, and 1835 saw the commencement of Yarrell's 'British Fishes,' followed by Bell's 'British Quadrupeds' in 1836, Yarrell's 'British Birds' in 1837, and a series of recognized classics on British Crustaceans, Zoophytes, Starfishes, &c. As specimens of wood-engraving, the cuts by Sam Williams and John Thompson in Selby's 'British Forest Trees' (1842) show the perfection attained in an art now less practised; while the illustrations to Yarrell's 'British Birds,' including the vignettes, show how nearly black-and-white can indicate colour. After a long and prosperous career, Van Voorst retired from business in favour of his assistants, Messrs. Gurney & Jackson, in 1886; but his genial interest in old friends and a younger generation of naturalists never flagged until, on the completion of his ninety-fourth year, the exhaustion of natural forces began to make itself apparent. For many of the above facts we are indebted to the obituary notice which appeared in the ' Athenæum.'