Thoreau: His Home, Friends and Books/Chapter 7

CHAPTER VII

THOREAU AND HIS FRIENDS

ARISTOTLE was one of Thoreau's favorite authors; it would seem as if the New England poet-philosopher applied in his life the definition of friendship given by the Greek sage,—"One soul abiding in two bodies." The affinity demanded by Thoreau is seldom approximated in the most perfect loyalty of friends. In the essay, first published in "A Week," are many rhapsodic suggestions akin to Emerson's transcendental ideas upon the same theme of friendship. Thoreau's aspiration, which became virtually an exaction, was that the true friend, "a pure, divine affinity," should be so closely in touch with his friends, in their thoughts especially, that he should treat them "not as what they were, but as what they aspired to be." In turn, the true friend will be content with this recognition of his potential nobleness and will ask no other boon. He will strive daily to merit such apotheosis,—"Friends should live not in harmony but in melody."

It has been suggested, with some plausibility, that Thoreau's romantic and poetic ideas on friendship were closely linked with his early repressed love. Moreover, his insistence on the bond of relation, which needs no explanations, was accordant with his peculiar reticence and independence, no less than his absolute sincerity. There are sentences, especially in his early writings, vibrant with memory of the tender heart-love between man and woman, while some of his later words on friendship seem iterations of this deep, unsatisfied affection. His thoughts on "Love and Chastity" are unsurpassed in beauty of concept and form;—"A hero's love is as delicate as a maiden's. . . . We should not surrender ourselves heartily to any while we are conscious that another is more deserving of our love." Perchance that subtle sentence explains Thoreau's refusal to entertain thoughts of marriage, though his friends assure us that two women were quite willing, even anxious, to link their lives with his. In one letter to Emerson he makes a quiet, firm reference to such fact and his immediate decision. ("Familiar Letters," p. 116.)

His few references to love between the sexes, however, are submerged beneath the more generic love of friends, without which our life is "like coke and ashes." Thoreau's lofty aspirations were, of necessity, often unfulfilled, as his letters and journals indicate. Explanations and testimonies seemed to him an insult to friendship. He acknowledges this inability on his own part to resort to confessions and guarantees, a reserve due not to pride, he says, but to his assured faith that the true friends will understand without explanations, which merely cheapen a loving relationship. His friend's atmosphere must be fully in accord with his own or "it is no use to stay." The language of friendship must be, not in words, but in latent, constant affinity.

In spite of these somewhat nebulous visions of the poet, Thoreau in daily life, was one of the most generous, helpful friends. Channing said with truth,—"He was at the mercy of no caprice; of a reliable will and uncompromising sternness in his moral nature, he carried the same qualities into his relations with others, and gave them the best he had, without stint." His real value as a friend, as too often is the case, received the first, full recognition in his obituary notices. He had tried to apply his own ideals in his friendships; he had loved freely, unchangingly, as he loved God, "with no more danger that our love will be unrequited or ill-bestowed." In later life, however, he grieved over some criticisms and misunderstandings on the part of some earlier friends. Frequent references regret that he is regarded as "cold" and too reserved. To him such criticism seemed merely a divergence of friendship, a lack of true, warm entente. No reader can fail to note the tone of gentle sadness which Thoreau displayed when commenting on such misinterpretation of his steadfast loyalty, which he could not stoop to repeat in mere words. With a tender patience, he wrote of his death,—"And then I think of those amongst men who will know that I love them, though I tell them not."

Perhaps such persistence in reserve and aspirations indicated, to a surface reader, a super-sensitive, impractical, even obstinate, temperament. Granting the existence of some natal qualities of this sort, these lofty ideals were also the expression of the poet and the moral reformer. They resulted from his acceptance of many transcendental beliefs, from his appeal to the intuitive, spiritual nature. Among significant notes that illumine this theme is the journal paragraph, in "Winter," for December 12, 1851;—"In regard to my friends, I feel that I know and have communion with a finer and subtler part of themselves which does not put me off when they put me off, which is not cold to me when they are cold, not till I am cold. I hold by a deeper and stronger tie than absence can sunder." Again, in March, 1856, he refers to two friends who failed to meet his tests of friendship, one who offered friendship "on such terms that I could not accept it without a sense of degradation," who sought to patronize him; the other, through obtuseness, "did not recognize a fact which the dignity of friendship would by no means allow me to descend so far as to speak of, and yet the inevitable effect of that ignorance was to hold us apart forever." Without any offensive details intime, how fully these comments reveal the dignity and lofty uprightness, the delicacy and nobleness of Thoreau's heart and soul!

To a casual thinker, it might seem as if a man who had such cerulean ideals for friendship, who mingled a supersensitiveness and severity in his demands, would find few practical friends who could approximate his standards. On the contrary, Thoreau was a friend, deeply loved and eagerly sought by men and women of diverse natures. With all his ideal demands, he mingled a rare charity for actual words and acts; he was personally humble and full of practical aid. He was ready to appreciate the services of his friends, capable of understanding their generous motives, even better than their impulsive acts, he was a cheerful, intellectual comrade, though always disparaging his own merits in idealizing the qualities of his friends. He once declared that his distinction among his friends must be that "of the greatest bore they ever had." Among some passages from letters to his Western correspondent, Mr. Greene, is a comment, called forth by an expressed desire to see Thoreau, in which he derides himself as "the stuttering, blundering, clodhopper that I am, not worth a visit."

While he was a wise and entertaining comrade and a practical helper in any possible way for his friends, he was especially venerated by some as a father-confessor and a spiritual guide. Mr. Emerson, in his funeral eulogy, referred to the worship given Thoreau by those who recognized his qualities of soul as well as brain; his letters and those of his sister testify to the many requests for advice, both on practical and moral themes, during his later life, and the wide-spread appeal to him for inspiration and courageous incentive. While always ready to aid where his words or acts could do real service, he disliked any semblance of dogmatism, he never posed as a preacher or prophet, and in many cases answered the requests for advice by a dignified, courteous refusal, and an adjuration to the seeker to consult his own higher nature and educate his own conscience to become his guide. Among his friends, none has more fittingly commemorated his

"Thus Henry lived,

Considerate to his kind. His love bestowed

Was not a gift in fractions, half-way done;

But with some mellow goodness like a sun,

He shone o'er mortal thoughts and taught their buds

To blossom early, thence ripe fruit and seed.

Forbearing too oft counsel, yet with blows

By pleasing reason urged he touched their thought

As with a mild surprise, and they were good,

Even as if they knew not whence that motive came,

Nor yet suspected that from Henry’s heart—

His warm, confiding heart,—the impulse flowed."

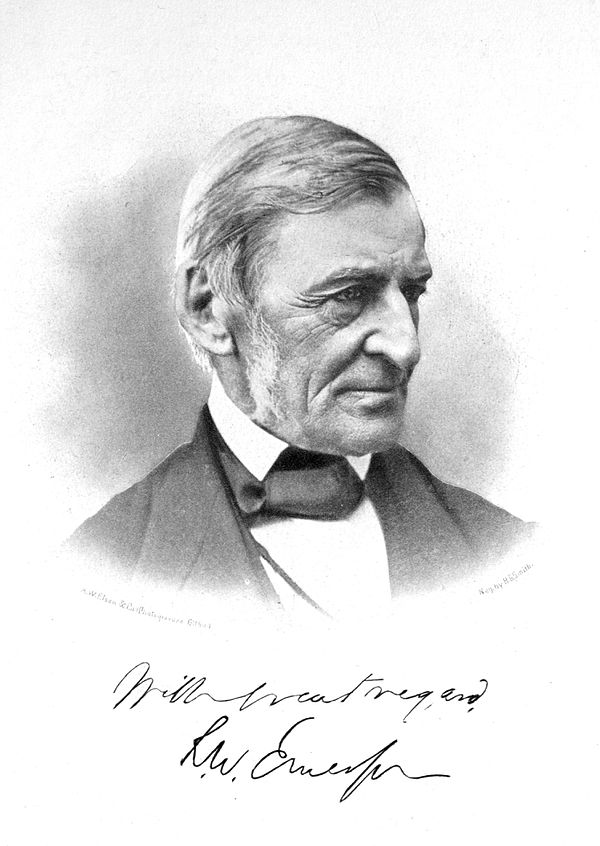

At mention of Thoreau's friends, the memory at once reverts to Emerson, as the first and most illustrious friend of Thoreau's manhood. The influence of that friendship and their mutual services will always be mooted subjects. Some earlier critics, like Lowell, or those persuaded by his words, regarded Thoreau as Emerson's progeny,—"a pistillate plant" of his pruning. Others, with strained effect, explain the character of Donatello as the awakening of Thoreau's soul, under the influence of Emerson, as witnessed and recorded by Hawthorne. On the other hand, there are critics, like Dr. Japp, who deplore the temporary influence of Emerson as deleterious to Thoreau's true development as poet. No one can question the stimulative effect, emotionally and mentally, of Thoreau's early friendship with Emerson and residence in his home. The time is past, however, to accept the theory that his genius was reflected light from Emerson or that his fame has been due to the association of the two names.

By those who would thus regard Thoreau as imitator of Emerson, much stress was laid upon the resemblances in manner and voice, and this was construed as conscious or unconscious expression of the dominant influence of Emerson upon his younger friend. The words of Rev. David Haskins, a college classmate of Thoreau and a cousin of Emerson, have been widely quoted;—"Not long after I happened to meet Thoreau in Mr. Emerson's study at Concord the first time we had come together since leaving college. I was quite startled by the transformation that had taken place in him. His short figure and general cast of countenance were of course unchanged; but in his manners, in the tones of his voice, in his mode of expression, even in the hesitations and pauses of his speech, he had become the counter part of Mr. Emerson." Though such statement is extreme, according to the testimony of many Concord friends, there did exist strange resemblances of manner as well as of mind, but they were largely

coincidal. To both, nature had given musical, mellow voices, and these had been further likened by the subtle effect of companionship. A Concord friend of both Emerson and Thoreau recently said to me,—"One might as well assert that Thoreau's nose was an imitation of Emerson's," for both had the aquiline Roman features. Unconsciously, Thoreau confided to his journal an incident which throws light upon this resemblance, a passage that has not been quoted in this connection. In the brief account of his part, in 1859, in speeding one of John Brown's accomplices from Concord to Canada, while they were driving to Acton for a train, he recounts the fugitive's urgent request to find Emerson, that he might discuss some plans with him. So eager was the fanatic to gain his end that he once jumped from the carriage but was speedily reinstated by Thoreau who drove quickly forward. Recognizing that the man was partly insane, Thoreau records, "At length when I made a certain remark, he said, I don't know but you are Mr. Emerson; are you? You look somewhat like him.' . . . He said this as much as two or three times." ("Autumn," pp. 381-2.) Thus, in later as in earlier years, the similarity of features was noticed, and the coincidences of thought have been themes for wonder, from their discovery by Helen Thoreau to the present day.Clearly, Emerson at no time regarded Thoreau as his imitator or unconscious reflector. He always emphasized the peculiar and original ability of his friend. If the maturity of Thoreau's life brought disappointment to Emerson, it never changed his belief in the possibilities of mind and literary power in the younger man. When at the request of Sophia Thoreau, Emerson read her brother's journals, the year after the death of their owner, he recorded, not in generous adulation, but in his own private journal, the words on Thoreau;—"In reading him, I find the same thoughts, the same spirit that is in me, but he takes a step beyond, and illustrates by excellent images that which I should have conveyed in a sleepy generalization. 'Tis as if I went into a gymnasium and saw youths leap, and climb, and swing, with a force unapproachable, though their feats were only continuations of my initial grapplings and jumps." Here is hint of the similitude and difference in the two minds, born and trained under the same intellectual influences. Emerson's trend was towards generic, soul-uplifting thoughts; Thoreau's towards the specific and illustrative, yet no less lofty.

A critic has said that during Thoreau's later life his relations with Emerson became "Roman and austere." These are extreme terms to apply to a friendship which never lost the bases of mutual respect and love but which suffered certain strains of difference in opinion, as the years passed. Emerson was deeply, vitally interested in Thoreau's future and anticipated great results for him and the world. Writing to a friend of Carlyle's expected visit to America about 1840, Emerson mentioned that he should introduce Thoreau as "the man of Concord." Recognizing the masterly powers of intellect and will in Thoreau, his friend prophesied for him leadership in literary and state affairs. In this forecast he had failed to give sufficient weight to certain marked limitations and unswerving tenets in Thoreau's character. Emerson possessed a remarkable poise and serene wisdom. He was victim of no impulses and intense passions. In philosophical and practical ideas alike, he was foresighted and calm. He never allowed his devotion to principle and reform to commit him to words or acts of extreme radicalism. When he left the church over which he ministered, because he could not accept the need of the eucharist, he made no bombastic scene. In his essays he uttered some startling and misty iconoclasms of thought and aim, but when he read these words or discussed his principles, he was always controlled, always tolerant of the views of others. In brief, he always exercised a wise, gracious caution and patience, qualities which, added to the paramount influence of his presence. Full of the desire for reform of individual life and general society, until the critical decade of the wide-spread anti-slavery movement, he never lent his name nor influence to any rabid or extreme methods. He could not understand that intense devotion to ideas of abstract government which brought Thoreau to jail for non-payment of taxes. He regretted, also, the tenacious refusal of his friend to accept opportunities for travel and progression in worldly ways. As he once hinted, it was a grief to him that a man, fitted to be a leader of men in thought and action, should be content to become merely "a leader of huckle-berry parties of young people." In the Concord circle of his day, and in the wider world of public opinion since, Emerson, with his balanced judgment, his broad and cautious respect for custom and affairs of state, his serene yet no less magnetic aspirations for a gradual, sure adjustment of conditions that would effect a more simple, sincere civilization, has gained greater honor than his more radical pupil-friend, Thoreau. The latter, as Emerson recognized in his comments on the journal already quoted, carried to extreme issues many of the seething, perplexing ideals of the day, though saved from association with the radical communities by his individualism.

As life advanced, the divergencies in mind be tween Emerson and Thoreau became more marked because of their temperamental traits. Nature had given to Emerson adroitness and keenness, mollified by calm, kindly judgment. Thoreau, on the contrary, despite his attained serenity of soul, was sometimes moved by wrong and injustice to Carlylean indignation. While always courteous in its highest sense, Thoreau's mental attitude was, at times, combative and irascible. To Emerson's sunny soul, he seemed, occasionally, "with difficulty, sweet." His wit was sometimes acrid in arguments, while his reserve and refusal to explain led, to many transitory misunderstandings. If the relations between Emerson and Thoreau in later life were less intimate, they were no less friendly. Both formed other acquaintances with whom affinity and propinquity fostered greater intimacy. Thoreau was conscious of Emerson's disappointment and criticism, he felt both keenly, though he gave no specific expression, but he became more reserved outwardly to hide the inward sensitiveness. Moreover, reserve was not the exclusive attribute of Thoreau. Many of Emerson's friends complained of inability to reach his inner self. In answer to such a charge from Margaret Fuller, Emerson acknowledged such barriers to any intimacy between himself and others and called himself "an unrelated person." Henry James, Senior, openly declared that he could not probe the misty, calm reserve of Emerson, "who kept one at such arm's length, tasting him and sipping him and trying him."

It is not strange that Emerson truly believed that Thoreau's desire was to become a stoic. He did not know, until after Thoreau's death, many of the dormant, submerged evidences of tender heart-love. His funeral address, so widely read and quoted, revealed his deep admiration for his friend, but it also showed that, doubtless unwittingly, he had lost sight of some of the nobler and gentler qualities of Thoreau's nature. In a reminiscent sketch by Mrs. Rebecca Harding Davis, entitled "A Little Gossip," in Scribner's Magazine for November, 1900, she emphasizes Emerson's delight in the study of men and women, as a scientist would study specimens. This acute probing extended even to his friends and, as the years caused lapse of full memory, occasioned some comments of seeming disloyalty. To Mrs. Davis, a few years after Thoreau's death, he said;—"Henry often reminded me of an animal in human form. He had the eye of a bird, the scent of a dog, the most acute, delicate intelligence. But no soul. No, Henry could not have had a human soul." While Emerson, in his inner truth, did not mean this analysis as it may sound to a casual reader, one cannot refrain from regret that such a half-truth should have been uttered and printed. Would Thoreau ever have said such enigmatical words of a friend? Such extreme and unexplained criticisms, sometimes uttered during Thoreau's life, must have caused deep grief to his proud, sensitive heart. His own published journal-extracts and letters, and the testimony of his sister and many friends, have fully established the warmth and constancy of the controlled emotional and spiritual qualities. Dr. Edward Emerson has well summarized this relationship between his father and Thoreau; "In spite of these barriers of temperament, my father always held him, as a man, in the highest honor."

Thoreau's kindly humanity and his rare fitness as companion were fully recognized by the Emerson household during his residence there. If the gentler traits were sometimes hidden from Emerson, they were revealed to Mrs. Emerson and the children, who have given the world loving memories of this household friend. In the "Familiar Letters" Mr. Sanborn has shown the tender, ennobling influence which Mrs. Emerson exerted upon Thoreau. One must also recognize her reciprocal regard and respect. This woman, who has been well described as "grace personified," in whom her husband found true embodiment of all Christianity, educed the finer and nobler qualities of Thoreau's heart and soul. In deep earnestness, which escaped all reserve, he wrote to her from Staten Island;—"The thought of you will constantly elevate my life; it will be something always above the horizon to behold, as when I look up at the evening star." With Mrs. Emerson, Thoreau discussed poetry and philosophy; he was elevated to his loftiest mental ascents, and again wrote,—"I feel taxed not to disappoint your expectation." In practical ways he was ever ready to aid her artistic efforts at gardening, and he alludes with gentle humor to this profession of his hostess-friend.

After noting the gentle inspiring influences of the Emerson home and child-life there upon Thoreau, one can readily believe that had the love of a husband and father come into his life, during these formative years, his emotional nature would have shown greater expansion and less constraint. Doubtless, there might have resulted a loss of mental independence and exclusive devotion to nature and poetry. For children, he had to the end of his life the deepest affection. He was justly popular with them as teacher and story-teller. An incident which showed his tactful method of instruction, is recalled by one of the town children, who was often a member of his huckleberry-parties. When some child, in climbing a fence or scaling a wall, fell and lost his berries, Thoreau tenderly supplied the fruit from his own pail and then explained to the little ones how fortunate the mishap really was, since thus must seed be supplied for future berries. Among all Concord children, the girls and boy of the Emerson home retained his deep love to the close of life. He would tell them stories, replete with fancy and fact from natural history, he would organize and lead their excursions, or would champion their childish causes. He writes, with loving pride, that young Edward "asked me the other day, Mr. Thoreau, will you be my father? I am occasionally Mr. Rough-and-Tumble with him that I may not miss him, lest he should miss you too much." Again, to the absent father, he writes: "Ellen and I have a good under standing. I appreciate her genuineness. Edith tells me after her fashion,—'By and by I shall grow up and be a woman, and then I shall remember how you exercised me.'" ("Familiar Letters," p. 162.)

Thoreau's friendship with the Emerson family was ever a tender memory to him. When he left that home he wrote the poem, "The Departure," not printed until many years later, but expressing his gratitude in earnest, gracious words:—

******

"This true people took the stranger,

And warm-hearted housed the ranger;

They received their roving guest,

And have fed him with the best;

"Whatsoe’er the land afforded

To the stranger’s wish accorded,—

Shook the olive, stripped the vine,

And expressed the strengthening wine.

******

"And still he stayed from day to day,

If he their kindness might repay;

But more and more

The sullen waves came rolling towards the shore.

"And still, the more the stranger waited,

The less his argosy was freighted;

And still the more he stayed,

The less his debt was paid."

Outside the Emerson household, perhaps rather closely related to it, was the first Concord friend to recognize the genius of Thoreau, anterior and preparatory to his acquaintance with Emerson. Mrs. Lucy Brown of Plymouth, the sister of Mrs. Emerson, who spent a large part of her years in Concord, was the caller to whom Helen Thoreau showed her brother's journal, with pride that it contained sentences like those of Emerson. As recorded, Mrs. Brown borrowed the journal to show to her brother-in-law and thus laid the foundation for that famous literary friendship. For Mrs. Brown, as for her sister, Thoreau felt that romantic and reverential friendship which many a young man of poetic mind entertains for matrons of intellect and gracious character. Mrs. Brown especially encouraged Thoreau's poetic aspirations. Into her window he threw the copy of those early self-revelatory lines, perchance his best work in verse, "Sic Vita," beginning,—

"I am a parcel of vain strivinga, tied

By a chance bond together."

With the poetry of gracious act as well as words, he placed this scrap of verse about a bunch of violets, a delicate and romantic deed for the stoic and hermit! To her he wrote, ("Familiar Letters," p. 44,) "Just now I am in the mid-sea of verses, and they actually rustle around me as the leaves would round the head of Autumnus himself should he thrust it up through some vales which I know; but alas! many of them are but crisped and yellow leaves like his, I fear, and will deserve no better fate than to make mould for new harvests." During these years of young manhood, Thoreau confided to this friend his ideals, his dreams, and his rare delight in nature. To her also, he complained of his unfitness for practical work; again, in a letter to her, already mentioned, he wrote one of his very few references to the death of his brother, John.

The names of Thoreau and Alcott have been often linked as vague idealists; both have also been called imitators of Emerson. It was once said of Alcott, with more wit than justice, "Emerson is the seer,—and Alcott the seer-sucker." While Alcott and Thoreau were friends, while both were extreme idealists, while both placed the soul-nourishment far superior to the body-maintenance, while both contended for reform from the drudgery and extravagance of society, they had wholly dissimilar natal traits. Alcott's serene, unanxious acceptance of practical perplexities caused Thoreau grave speculation; the artistic and improvident nature of Alcott, always impractical and easily duped, was in marked contrast to the exact, shrewd, busy temperament of Thoreau, who was a model of Yankee in genuity and thrift, no less than type of nature-poet and philosopher. Reference has been made to the Emerson garden-study, designed by Alcott and condemned by Thoreau for its geometric and mechanical defects. Thoreau, however, always had a tender regard for the mystical, Platonic philosopher, whose idea of heaven was "a place where you could have a little conversation." Writing to Emerson, Thoreau said of Alcott,—"When I looked at his gray hairs, his conversation sounded pathetic; but I looked again, and they reminded me of the gray dawn." To the end of his life, Thoreau, though conscious of all his friend's defects, recognized his aspirations and his purity of character. He found pleasure in walks and, when strength failed, in long talks with him. In turn, Alcott had a loyal love for Thoreau and a deep respect for his qualities of mind and poetic vision. In a letter to Mrs. Thoreau, (after her son's death), now first printed, Alcott said,—"We may be sure of his being read and prized by coming times, and the place and time pertaining to him shall be forever the sweeter for his presence."

Thoreau was a constant friend to the Alcott family; Louisa mentions his name among the bearers at the funeral of her sister Beth, and other memories by the sisters attest their cordial relations with him and his family. Among the keen characterizations of his Walden visitors, is the excellent pen picture of Alcott:—"One of the last of the philosophers,—Connecticut gave him to the world,—he peddled first her wares, afterwards, as he declares, his brains. These he peddles still, prompting God and disgracing man, bearing for fruit his brain only, like the nut its kernel. I think that he must be the man of the most faith alive. His words and attitude always suppose a better state of things than other men are acquainted with, and he will be the last man to be disappointed as the ages revolve. . . . think that he should keep a caravansary on the world's highway, where philosophers of all nations might put up, and on his sign should be printed, 'Entertainment for man, but not for his beast. Enter ye that have leisure and a quiet mind, who earnestly seek the right road. A blue-robed man, whose fittest roof is the over arching sky which reflects his serenity. I do not see how he can ever die; nature cannot spare him.'"

At one time Thoreau quoted Alcott as saying were he and Ellery Channing to live in the same house, they "would soon sit with their backs to each other." Both these poet-philosophers, diverse in temperament, united in a common devotion to Thoreau, and, in time, gained that mutual sympathy which ended in firm friendship for each other. Channing, the last survivor of this famous Concord group, passing away in December, 1901, was, in truth, "the last leaf upon the tree," of transcendental poetry. He possessed, to the last, a strange, contradictory personality and a unique, neglected genius. By his own confession and the attestation of all his friends, he was a man of sudden, vacillating moods, with a perversity and improvidence which often brought despair to his own heart and home-circle. His was a heritage of high ideals and liberal intellect as his name, like that of his noble uncle, testified. After his college life was ended, and experimental years passed in various places, including a brief period in Illinois log-cabin life, he came to Concord in 1843. A few months younger than Thoreau he soon became his constant comrade after the death of John Thoreau. Emerson, also, found in Channing a stimulative companion on woodland walks. Both Channing and Thoreau, in their early poetic efforts, incurred the exaggerated criticism of being mere imitators of Emerson. In "A Fable for Critics," Lowell has clearly sneered at these two friends in the lines,—

"There comes . . . (Channing), for instance; to see him's rare sport

Tread in Emerson's tracks with legs painfully short;

*******

"He follows as close as a stick to a rocket,

His fingers exploring the prophet's each pocket.

Fie! for shame, brother bard; with good fruit of your own,

Can't you let neighbor Emerson's orchards alone?

Besides, 'tis no use, you'll not find e'en a core,—

. . . (Thoreau) has picked up all the windfalls before."

Thoreau seems to have educed the lovable, companionable qualities of this moody poet, though he was keenly conscious of his peculiarities. Professor Russell, who recalls Channing on an occasion of a visit to Concord and an evening at the Old Manse, has spoken of the gracious, inspiring companion that he found in him, on their return walk to the town. In "Walden," Thoreau recounts the visits of this friend, then coming all the distance from the hilltop of Ponkawtasset to the little lodge, where they enjoyed hours of "boisterous mirth" and serious talk and made "many a bran new theory of life over a thin dish of gruel." Channing's memorial verses and biography, no less than his poems, "The Wanderer" and "Near Home," have been among the most tender and illuminating revelations of Thoreau's mind and soul.

The world has ignored the poems of Channing, though they contain many rare thoughts and beautiful images. He carried to a far greater excess the philosophic trend and uneven, independent metres, which characterize the poetry of Emerson and Thoreau, yet he had deeper passion and more absorbing subjectivity than either of his friends. In "A Week," Thoreau refers with discriminating sympathy to the earlier poems of Channing, "whose fine ray,

Doth often shine on Concord's twilight day,

Like those first stars, whose silver beams on high

Most travelers cannot at first descry,

But eyes that wont to range the evening sky"

Allusion has been made to the Sunday afternoon visits, at the Walden hut, of Edmund Hosmer, "who donned a frock instead of a professor's gown." This farmer of the exalted olden type, was the intimate adviser of Emerson and Thoreau on matters of varied import and, with him, their relations were always cordial and sympathetic. He is associated, also, with the Concord experience of George William Curtis. He was a man of strong, clear brain, keen judgment, and poetic instincts, whose home reeked with plenty and hospitality. His daughters, in their Concord home, with rare memorials and memories of the days of yore, are gracious, wise dispensers of their noble inheritance. Emerson's paper in The Dial for July, 1842, on "Agricultural Survey in Massachusetts," reflected his conversations with Mr. Hosmer. In his study of Brook Farm life, Mr. Lindsay Swift asserts that Emerson's decision, not to join this community, was due to the sagacious warnings of his farmer-friend. Hawthorne has, also, well portrayed Mr. Hosmer, with "his homely and self-acquired wisdom, a man of intellectual and moral substance, a sturdy fact, a reality, something to be felt and touched, whose ideas seemed to be dug out of his mind as he digs potatoes, beets, carrots, turnips, out of the ground." It required no strained imagination to realize the delight which Thoreau ever found in the companionship of such an invigorating presence, a modern Cato or Varro.

Among the widely quoted thoughts of one of Thoreau's biographers is the statement that Channing, in a measure, was the interpreter between Hawthorne and Thoreau. While both the naturalist and the romancer found a companion in Channing, there is much evidence, both in Hawthorne's notebooks and in the letters of Thoreau, that, from the first appearance of Hawthorne at Concord, there existed a warm sympathy between himself and the poet-naturalist. Thoreau was among the few guests at table at the Old Manse; together they listened to the music-box, sailed upon the river, or sauntered along the wood-paths. For Thoreau, Hawthorne had deep regard both as nature-poet and "as a wholesome and healthy man to know." The famous little boat, in which the brothers had journeyed along the Concord and Merrimack, became the property of the romancer, was rechristened "The Water-Lily," and constantly reminded its owner of the marvelous skill of Thoreau with the paddle and the oar. When Thoreau went to Staten Island, Hawthorne saw the wisdom of the change for physical reasons, but added the regret,—"On my own account I should like to have him remain here, he being one of the few persons, I think, with whom to hold intercourse is like hearing the wind among the boughs of a forest tree; and, with all this wild freedom, there is a high and classic cultivation in him too." Of the review of a series of papers which Thoreau contributed to The Dial, Hawthorne wrote in his note-book,—"Methinks this article gives a very fair image of his mind and character,—so true, innate and literal in observation, yet giving the spirit as well as the letter of what he sees, even as a lake reflects its wooded banks, showing every leaf, yet giving the wild beauty of the whole scene. . . . There is a basis of good sense and of moral truth, too, through out the article, which, also, is a reflection of his character." Scarcely did Thoreau need an interpreter with a friend who could thus understand and illumine his mind and soul.

One cannot leave the Concord friends without mention of Elizabeth and Edward Hoar, who recognized the genius of Thoreau and his nobleness of character, while to him they showed many proofs of sincere friendship. On his departure for Staten Island, Elizabeth Hoar gave him the ink-stand to which his letters refer. In a cordial note, given with the remembrance, she wrote,—"and I am unwilling to let you go away without telling you that I, among your other friends, shall miss you much and follow you with remembrance and all the best wishes and confidence." Thoreau was deeply appreciative of such friendship from the noble woman, whom Emerson always regarded as sister, after the death of his brother Charles to whom she was betrothed, and whose presence, says Emerson, "consecrates." Thoreau mentions her with reverence as "my brave townswoman, to be sung of poets." Edward Sherman Hoar, her brother, was one of Thoreau's later friends and contributed to him many comforts during the last months of weakness. Though some years his senior, Thoreau found in Hoar a delightful comrade in mountain excursion and woodland tramp, as long as strength allowed. To the kind thought of this friend, he owed the long drives which gave him mild exercise and refreshing air, after the body had lost its pristine vigor. Mr. Hoar was, for many years, a magistrate in California; on his return to Concord, he preferred the quiet life of a scholar and nature-student, and in Thoreau he recognized a magician-teacher. The epitaph of Mr. Hoar accentuates the qualities which made the two men so congenial;—"He cared nothing for the wealth or fame his rare genius might easily have won. But his ear knew the songs of all birds. His eye saw the beauty of flowers and the secret of their life. His unerring taste delighted in what was best in books. So his pure and quiet days reaped their rich harvest of wisdom and content."

Outside other local friends, among whom Mr. Sanborn has exemplified his friendship by the biographical and editorial work to which all students of Thoreau are deeply indebted, he had a practical adviser and business colleague in Horace Greeley. For Thoreau, Greeley arranged terms for articles in Graham's, Putnam's, and other magazines, advanced him money for literary uses, and tenaciously gained for him the long-deferred remuneration from editors. He was ever appreciative of the ability of Thoreau and somewhat shared the regret of Emerson at the non-fulfilment of a wider literary fame for his young friend. When Thoreau first called upon Greeley in New York, he was impressed by the kindly greeting,—"now be neighborly"—and described this busy, erratic editor as "cheerfully in earnest, a hearty New Hampshire boy as one would wish to meet." ("Familiar Letters," p. 114.)

Among Thoreau's earlier friends, to become also his literary critic, was Margaret Fuller. "While editor of The Dial, she examined,—and rejected,—some of his poems and essays. Appreciating that their author was "healthful, rare, of open eye, ready hand, and noble scope," she also saw in him "a somewhat bare hill, which the warm gales of spring have not visited." Her censure was keen, and well emphasized the startling beauties, combined with the sternness and ruggedness of much of Thoreau's early writing. Though Margaret Fuller was in Concord often for many years, and met Thoreau constantly at the homes of his friends, their relations were never very cordial on the part of Thoreau. Like Emerson, he appreciated the mental gifts of this woman, the "new woman" type of her day, but her efforts to win intimate friendship failed to gain response from either author. The "repulsions," which Emerson records with regret against her personality, were shared by many acquaintances in both Concord and Boston. Some of the sentences in "A Week" are often explained as personal references to Margaret Fuller;—"a restless and intelligent mind, interested in her own culture, who not a little provokes me, and, I suppose, is stimulated in turn by myself." After the tragic shipwreck and drowning of Margaret Fuller Ossoli, with her husband and son, Thoreau was one of the first family friends to hasten to the coast off Fire Island, to give service and care to her mother and brother. The latter, Richard Fuller, was a valued comrade of Thoreau on many excursions, and to him he owed his treasured music-box.

In Thoreau's later life he carried on an extended revelatory correspondence with two men of poetic and meditative minds, who justly deserve rank among his most devoted and appreciative friends. One of these was Mr. Daniel Ricketson of New Bedford. The acquaintance began in 1854, as a result of the purchase of a copy of "Walden." The letters continued until Thoreau's death, with frequent interchange of visits; in truth, Mr. Ricketson remained a cordial friend to the family after Thoreau's death. His many letters to Miss Sophia Thoreau, which it has been my privilege to read, reveal a character of rare insight and religious beauty. He was a poet-botanist and had built, and occupied for hours daily, a "shanty" near his beautiful home in New Bedford. Thoreau, who was much interested in the flora of this region and in the marine plants of Nantucket, often visited this friend from 1854 until 1861. As mentioned, it was on the last visit that the ambrotype was taken from which the Ricketson medallion was made. It was this friend who described the first sight of Thoreau, as he approached his home unexpectedly, with "a portmanteau in one hand and an umbrella in the other," looking "like a peddlar of small wares." To offset any suspicion of reproach for this initial vision, however, Mr. Ricketson always testified to the courtesy and fine-breeding of Thoreau as host or guest. In one of the letters to Miss Sophia, this friend gives a true glimpse of his own composite nature, which would so fully satisfy the ideals of his philosopher-teacher,—"Busy about farm-work but not neglectful of the Muses."

Among the letters from Mr. Ricketson are two written to Thoreau during his last weeks of illness. In one he chronicles, with the accuracy of the naturalist and the rapture of the poet, the signs of incipient spring from the wild geese and the golden-winged woodpecker to the robin and the catkins, a surety that Thoreau retained, to the last, his strong interest in nature. The second letter is here reproduced entire; it shows the warm, noble friendship and also proclaims the sure faith of this Quaker poet-naturalist, a quality which enhanced the affinity between the two men:—

"The Shanty, Brooklawn,

"13th April, 1862.

"My Dear Friend:

"I received a letter from your dear sister a few days ago informing me of your continued illness, and prostration of physical strength, which I was not altogether unprepared to learn, as our valued friend, Mr. Alcott, who wrote me by your sister's request in February last, said that you were confined at home and very feeble. I am glad however to learn from Sophia that you still find comfort and are happy, the reward I have no doubt of a virtuous life, and an abiding faith in the wisdom and goodness of our Heavenly Father. It is undoubtedly wisely ordained that our present lives should be mortal. Sooner or later we must all close our eyes for the last time upon the scenes of this world, and oh! how happy are they who feel the assurance that the spirit shall survive the earthly tabernacle of clay, and pass on to higher and happier spheres of experience.

"'It must be so,—Plato, thou reasoneth well:—

Else whence this pleasing hope, this fond desire

This longing after immortality?'

"Addison,—Cato.

"'The soul's dark cottage, battered and decayed,

Lets in new light through chinks that time has made;

Stronger by weakness, wiser men become,

As they draw near to their eternal home

Leaving the old, both worlds at once they view

Who stand upon the threshold of the new.'

"Waller.

It has been the lot of but few, dear Henry, to extract so much from life as you have done. Although you number fewer years than many who have lived wisely before you, yet I know of no one, either in the past or present times, who has drunk so deeply from the sempiternal spring of truth and knowledge, or who in the poetry and beauty of every-day life has enjoyed more, or contributed more to the happiness of others. Truly, you have not lived in vain, your works, and above all, your brave and truthful life, will become a precious treasure to those whose happiness it has been to have known you, and who will continue, though with feebler hands, the fresh and instructive philosophy you have taught them.

"But I cannot yet resign my hold upon you here. I will still hope, and if my poor prayer to God may be heard, would ask that you may be spared to us awhile longer at least. This is a lovely spring day here,—warm and mild,—the thermometer in the shade at 62° above zero (3 p. m.). I write with my shanty door open and my west curtain down to keep out the sun,—a red-winged blackbird is regaling me with a querulous, half-broken song, from a neighboring tree just in front of the house, and the gentle wind is soughing through my young pines. . . . I wish at least to devote the remainder of my life, whether longer or shorter to the cause of truth and humanity,—a life of simplicity and humility. Pardon me for thus dwelling on myself.

"Hoping to hear of your more favorable symptoms, but committing you (all unworthy as I am) into the tender care of the great Shepherd, who 'tempers the wind to the shorn lamb,'

"I remain, my dear friend and counsellor,

"Ever faithfully yours,

"Dan'l Kicketson."

A man of Thoreau's courage of thought and act is sure to win hero-worship from young men of poetic, responsive natures. To Concord came occasional visitors from England, attracted by Emerson's fame. Such often returned impressed by the original force of Thoreau's mind and his life-example. Among these travelers was young Thomas Cholmondeley of Shropshire, England, who came to Concord in 1854 and lodged with the Thoreaus. He was the nephew of Bishop Heber, was a pupil of Arthur Hugh Clough at Oriel, and had been given letters by the latter for Emerson. He had already published a volume, "Ultima Thule," descriptive of a visit to a New Zealand colony. With Channing and Thoreau, he made some excursions to adjacent mountains and, in 1855, he returned to England to take part in the Crimean War. The correspondence, during the next few years, shows his devotion to Thoreau and the strong influence exerted by the simple, lofty ideals of the Concord naturalist. Clearly, this youth won from Thoreau a half-promise to visit him in England when the war was ended. For Thoreau's library and scholarly researches he sent a gift of peculiar value, fifty-four large, expensive volumes on Hindoo literature, many of them rare in America. Thoreau was delighted with this "nest of Indian books"; in a letter to a friend, he compared his joy of possession to what he might have experienced "at the birth of a child." In return he sent to Cholmondeley his own volumes, some of Emerson's, and a copy of "Leaves of Grass," which first aroused perplexing question in literary England over the unique genius of Whitman. In November, 1858, Cholmondeley came again to Concord and urged Thoreau to join him in a trip south, but the severe illness of Thoreau's father prevented. His letters disclose fine scholarship in this young Englishman, so soon to suffer tragic death abroad; he was well versed in past and current science and history; he was alert with the euphoria and hope of early manhood. Mr. Ricketson, who met him at Thoreau's home, mentioned a striking resemblance to George William Curtis. Devoted to Thoreau, he imbibed many of his ideas on the simplification of life. It is related that on his first visit he came to Concord with the customary luggage of a rich Englishman, not omitting a valet; the keen, caustic, yet philosophic comments of Thoreau on the superfluities of custom so influenced him that on his second visit he was most simply clad and unburdened by paraphernalia.

A mystery long lurked about a "Western correspondent" of Thoreau during his later years. He has been identified as Mr. Calvin Greene of Rochester, Michigan. The acquaintance arose, as did others of the later friendships, from the books which Thoreau had published. Mr. Greene was an ardent admirer of free, original thought and also an earnest student of nature. He was much impressed by the courage and lofty ideals of the author of "Walden," which he found and read by chance. He began and maintained an inspiring correspondence during the last years of his teacher's life. Some of the letters written by Thoreau to this man of secluded, ennobling life have been privately published by Dr. Jones of Ann Arbor.

There was one intimate friend of Thoreau's later manhood who, after the death of Miss Sophia, became her brother's literary executor, Harrison Gray Otis Blake. Their friendship was deeply spiritual, perhaps most closely approximating Thoreau's ideal,—"mysterious cement of the soul." In the letters to Mr. Blake, which are included in the collection by Emerson in 1865 and also in "Familiar Letters," are some of Thoreau's most unreserved confessions of heart and soul. He once wrote to this friend,—"it behooves me, if I would reply, to speak out of the rarest part of myself." It has been said that their relation was wholly intellectual and impersonal but such statement is unjust. To both men, the ideals and soul-problems outweighed mere mundane matters, but there was ever a bond of warm heart-sympathy between them. Blake gave to Thoreau the devotion and rapt admiration of a pupil-friend. Blake, however, was the elder by a few months; he had been in Harvard when Thoreau was there, graduating from the Divinity School in 1839, when Emerson, by his famous address, sent quivers of apprehension through Calvinist creeds. Mr. Blake became deeply interested in Emerson and adopted many of his theological tenets. He was himself a preacher at Milford, New Hampshire, when Emerson resigned his pastorate and received such sharp censure, especially from Professor Norton. Mr. Blake, indignant at the attacks on Emerson, wrote a letter of sympathy and thus began that earlier friendship which became the medium of the later paramount influence in the life of Blake.

Leaving the church as a permanent profession, since he refused to accept many of its dogmas, Mr. Blake taught school, first at Boston, in the old Park Church, and then came to Worcester, his native city. Here he had classes for many years. A son of Francis Blake, a noted lawyer, bearing the name of a famous ancestor, Mr. Blake was by birth and education a man of matchless refinement and scholarship. His home was a model of sincere dignity and hospitality, as Thoreau often witnessed. Thither he came frequently after the acquaintance began, through the agency of Emerson, in 1848; he visited, also, at the home of Mr. Theophilus Brown. As mentioned, Thoreau lectured often at

HARRISON GRAY OTIS BLAKE

Photogravure of a portrait from life the parlors of Mr. Blake. Together they made excursions to the adjacent hills and lakes. During the last four years of Mr. Blake's life he was a great sufferer. As long as he was able to walk, however, he carried the cane which had been Thoreau's,—a plain stick of black alder with the bark shaved away on one side and notched as a two-foot rule. This was of great service to its later owner and was valued, not alone for its association, but because it supplied him with exact measurement. His trait, par excellence in all things, like that of his master, was precision; he never "guessed," he always studied the actual truth in matters of physical as well as intellectual moment. With absolute precision he kept a diary, after the type of Thoreau's, with abundant reflections and a few events. The latter were of little variety in this quiet, scholarly life, the thoughts were many and varied. Though avoiding strangers, he was one of the most companionable of friends, and was so kindly and warm-hearted that, even at the age of eighty, he was known to his few intimates as "Harry" Blake. After the journals of Thoreau became his sacred trust, he spent his days in close study of the nature-observations and lofty ideals of this teacher. To his careful editing we owe the volumes,—"Early Spring in Massachusetts," "Summer," "Winter," "Autumn," and also a volume of selected "Thoughts." To the last week of his life, when the eye was almost past reading, he applied his mind to the work which had been his greatest inspiration and blessing.

One might search long to find two men of such moral fibre as were Thoreau and Blake,—for their characteristics in this regard were identical. At the memorial service following the death of Mr. Blake in 1898, his friend, Prof. E. Harlow Russell, to whom he has committed the Thoreau manuscripts, uttered this succinct sentence,—"He was such a man as rendered an oath in a court of justice a superfluity." Could more fitting word be found to express the moral perfection of Thoreau as well as Blake? The latter lacked the physical vigor and the vivacious instincts of his friend; he was subject to moods of depression as well as of exaltation; he was far more of a philosopher than a naturalist; he had poetic ideals but lacked the power of expressing them. Despite such minor differences his qualities of mind, heart, and soul were accordant with those of Thoreau to a degree almost incredible and unexampled. Appropriate for the epitaph of both was the title-line of a Worcester newspaper after Mr. Blake's memorial service,—"Devoted to Ideals of Highest Type." Thoreau's letters to this Worcester friend were of unusual length and details in matters of advice and soul-nutriment. They seem sometimes nebulous and mystic in ideality; again, they are replete with strong thought and practical suggestion. The sturdiness of tone often recalls the "Ice-water tonic" on a sultry day, in which Alcott once imaged the influence of Thoreau.

Every friend of Thoreau, in earlier or in later life, felt the elevating influence of his masterly mind, his rare vision of nature, his poetic conception of nature's laws and growths, his brave independence of living, and his unswerving adherence to the inner truth and spiritual ideal. Whether incited to deeper thoughts and less regard for the trivialities of life, inspired to a new understanding of the beauties and messages of birds and flowers, or nerved to requisite courage and self-reliance to meet the perplexities and depressions of daily life, each friend could repeat with Emerson,—

"The fountains of my hidden life

Are through thy friendship fair."