West African Studies/Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

AFRICAN CHARACTERISTICS

When we got our complement of Krumen on board, we proceeded down Coast with the intention of calling off Accra. I will spare you the description of the scenes which accompany the taking on of Kruboys; they have frequently been described, for they always alarm the new-comer—they are the first bit of real Africa he sees if bound for the Gold Coast or beyond. Sierra Leone, charming, as it is, has a sort of Christy Minstrel air about it for which he is prepared, but the Kruboy as he comes on board looks quite the Boys' Book of Africa sort of thing; though, needless to remark, as innocent as a lamb, bar a tendency to acquire portable property. Nevertheless, Kruboys coming on board for your first time alarm you; at any rate they did me, and they also introduced me to African noise, which like the insects is another most excellent thing, that you should get broken into early.

Woe! to the man in Africa who cannot stand perpetual uproar. Few things surprised me more than the rarity of silence and the intensity of it when you did get it. There

[To face page 63.

For Palm Wine.

is only that time which comes between 10.30 A.M. and 4.30 P.M., in which you can look for anything like the usual quiet of an English village. We will give Man the first place in the orchestra, he deserves it. I fancy the main body of the lower classes of Africa think externally instead of internally. You will hear them when they are engaged together on some job—each man issuing the fullest directions and prophecies concerning it, in shouts; no one taking the least notice of his neighbours. If the head man really wants them to do something definite he fetches those within his reach an introductory whack; and even when you are sitting alone in the forest you will hear a man or woman coming down the narrow bush path chattering away with such energy and expression that you can hardly believe your eyes when you learn from them that he has no companion.

Some of this talking is, I fancy, an equivalent to our writing. I know many English people who, if they want to gather a clear conception of an affair write it down; the African not having writing, first talks it out. And again more of it is conversation with spirit guardians and familiar spirits, and also with those of their dead relatives and friends, and I have often seen a man, sitting at a bush fire or in a village palaver house, turn round and say, "You remember that, mother?" to the ghost that to him was there.

I remember mentioning this very touching habit of theirs, as it seemed to me, in order to console a sick and irritable friend whose cabin was close to a gangway then in possession of a very lively lot of Sierra Leone Kruboys, and he said, "Oh, I daresay they do, Miss Kingsley; but I'll be hanged if Hell is such a damned way off West Africa that they need shout so loud."

The calm of the hot noontide fades towards evening time, and the noise of things in general revives and increases. Then do the natives call in instrumental aid of diverse and to my ear pleasant kinds. Great is the value of the tom-tom, whether it be of pure native origin or constructed from an old Devos patent paraffin oil tin. Then there is the kitty-katty, so called from its strange scratching-vibrating sound, which you hear down South, and on Fernando Po, of the excruciating mouth harp, and so on, all accompanied by the voice.

If it be play night, you become the auditor to an orchestra as strange and varied as that which played before Shadrach, Meshech, and Abednego. I know I am no musician, so I own to loving African music, bar that Fernandian harp! Like Benedick, I can say, “Give me a horn for my money when all is done," unless it be a tom-tom. The African horn, usually made of a tooth of ivory, and blown from a hole in the side, is an instrument I unfortunately cannot play on. I have not the lung capacity. It requires of you to breathe in at one breath a whole S.W. gale of wind and then to empty it into the horn, which responds with a preliminary root-too-toot before it goes off into its noble dirge bellow. It is a fine instrument and should be introduced into European orchestras, for it is full of colour. But I think that even the horn, and certainly all other instruments, savage and civilised, should bow their heads in homage to the tom-tom, for, as a method of getting at the inner soul of humanity where are they compared with that noble instrument! You doubt it. Well go and hear a military tattoo or any performance on kettle drums up here and I feel you will reconsider the affair; but even then, remember you have not heard all the African tom-tom can tell you. I don't say it's an instrument suited for serenading your lady-love with, but that is a thing I don't require of an instrument. All else the tom-tom can do, and do well. It can talk as well as the human tongue. It can make you want to dance or fight for no private reason, as nothing else can, and be you black or white it calls up in you all your Neolithic man.

Many African instruments are, however, sweet and gentle, and as mild as sucking doves, notably the xylophonic family. These marimbas, to use their most common name, are all over Africa from Senegal to Zambesi. Their form varies with various tribes—the West African varieties almost universally have wooden keys instead of iron ones like the East African. Personally, I like the West African best; there is something exquisite in the sweet, clear, water-like notes produced from the strips of soft wood of graduated length that make the West African keyboard. All these instruments have the sound magnified and enriched by a hollow wooden chamber under their keyboard. In Calabar this chamber is one small shallow box, ornamented, as most wooden things are in Calabar, with poker work—but in among the Fan, under the keyboard were a set of calabashes, and in the calabashes one hole apiece and that hole covered carefully with the skin of a large spider. While down in Angola you met the xylophone in the imposing form you can see in the frontispiece to this volume. Of the orchid fibre-stringed harp, I have spoken elsewhere, and there remains but one more truly great instrument that I need mention. I have had a trial at playing every African instrument I have come across, under native teachers, and they have assured me that, with application, I should succeed in becoming a rather decent performer on the harp and xylophone, and had the makings of a genius for the tom-tom, but my greatest and most rapid triumph was achieved on this other instrument. I picked up the hang of the thing in about five minutes, and then, being vain, when I returned to white society I naturally desired to show off my accomplishment, but met with no encouragement whatsoever—indeed my friends said gently, but firmly, that if I did it again they should leave, not the settlement merely, but the continent, and devote their remaining years to sweeping crossings in their native northern towns—they said they would rather do this than hear that instrument played again by any one.

This instrument is made from an old powder keg, with both ends removed; a piece of raw hide is tied tightly round it over what one might call a bung-hole, while a piece of wood with a lump of rubber or fastening is passed through this hole. The performer then wets his hand, inserts it into the instrument, and lightly grasps the stick and works it up and down for all he is worth; the knob beats the drum skin with a beautiful boom, and the stick gives an exquisite screech as it passes through the hole in the skin which the performer enhances with an occasional howl or wail of his own, according to his taste or feeling. There are other varieties of this instrument, some with one end of the cylinder covered over and the knob of the stick beating the inside, but in all its forms it is impressive.

Next in point of strength to the human vocal and instrumental performers come frogs. The small green one, whose note is like that of the cricket's magnified, is a part-singer, but the big bull frog, whose tones are all his own, sings in Handel Festival sized choruses. I don't much mind either of these, but the one I hate is a solo frog who seems eternally engaged at night in winding up a Waterbury watch. Many a night have I stocked thick with calamity on that frog's account; many a night have I landed myself in hailing distance of Amen Corner from having gone out of hut, or house, with my mind too full of the intention of flattening him out with a slipper, to think of driver ants, leopards, or snakes. Frog hunting is one of the worst things you can do in West Africa.

Next to frogs come the crickets with their chorus of "she did, she didn't," and the cicadas, but they knock off earlier than frogs, and when the frogs have done for the night there is quiet for the few hours of cool, until it gets too cool and the chill that comes before the dawn wakes up the birds, and they wake you with their long, mellow, exquisitely beautiful whistles.

The aforesaid are everyday noises in West Africa, and you soon get used to them or die of them; but there are myriads of others that you hear when in the bush. The grunting sigh of relief of the hippos, the strange groaning, whining bark of the crocodiles, the thin cry of the bats, the cough of the leopards, and that unearthly yell that sometimes comes out of the forest in the depths of dark nights. Yes, my naturalist friends, it's all very well to say it is only a love-lorn, innocent little marmoset-kind of thing that makes it. I know, poor dear, Softly, Softly, and he wouldn't do it. Anyhow, you just wait until you hear it in a shaky little native hut, or when you are spending the night, having been fool enough to lose yourself, with your back against a tree quite alone and that yell comes at you with its agony of anguish and appeal out of that dense black world of forest which the moon, be she never so strong, cannot enlighten, and which looks all the darker for the contrast of the glistening silver mist that shows here and there in the clearings, or over lagoon, or river, wavering twining, rising and falling; so full of strange motion and beauty, yet, somehow, as sinister in its way as the rest of your surroundings, and so deadly silent. I think if you hear that yell cutting through this sort of thing like a knife and sinking despairingly into the surrounding silence, you will agree with me that it seems to favour Duppy, and that, perchance, the strange red patch of ground you passed at the foot of the cotton tree before night came down on you, was where the yell came from, for it is red and damp and your native friends have told you it is so because of the blood whipped off a sasa-bonsum and his victims as he goes down through it to his under-world home.

Seen from the sea, the Ivory Coast is a relief to the eye after the dead level of the Grain Coast, but the attention of the mariner to rocks has no practical surcease; and there is that submarine horror for sailing ships, the Bottomless pit. They used to have great tragedies with it in olden times, and you can still, if you like, for that matter; but the French having a station 15 miles to the east of it at Grand Bassam would nowadays prevent your experiencing the action of this phenomenon thoroughly, and getting not only wrecked but killed by the natives ashore, though they are a lively lot still.

Now although this is not a manual of devotion, I must say a few words on the Bottomless pit. All along the West Coast of Africa there is a great shelving bank, submarine, formed by the deposit of the great mud-laden rivers and the earth-wash of the heavy rains. The slope of what the scientific term the great West African bank is, on the whole,

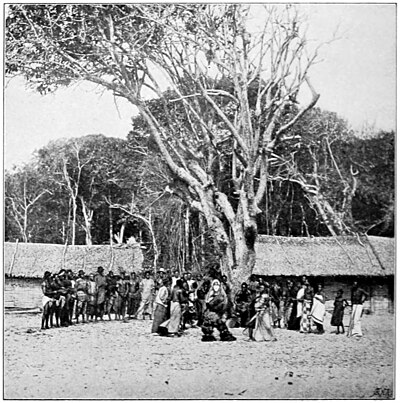

Secret Society Leaving the Sacred Grove

Jengu Devil Dance of King William's Slaves, Sette Camma, Nov. 9, 1888.

[To face page 69.

very regular, except opposite Piccaninny Bassam, where it is cut right through by a great chasm, presumably the result of volcanic action. This chasm commences about 15 miles from land and is shaped like a V, with the narrow end shorewards. Nine miles out it is three miles wider and 2,400 feet deep, at three miles out the sides are opposite each other and there is little more than a mile between them, and the depth is 1,536 feet; at one mile from the beach the chasm is only a quarter of a mile wide and the depth 600 feet—close up beside the beach the depth is 120 feet. The floor of this chasm is covered with grey mud, and some five miles out the surveying vessels got fragments of coral rock.

The sides of this submarine valley seem almost vertical cliffs, and herein lies its danger for the sailing ship. The master thereof, in the smoke or fog season (December—February), may not exactly know to a mile or so where he is, and being unable to make out Piccaninny Bassam, which is only a small native village on the sand ridge between the surf and the lagoon, he lets go his anchor on the edge of the cliffs of this Bottomless pit. Then the set of the tide and the onshore breeze cause it to drag a little, and over it goes down into the abyss, and ashore he is bound to go. In old days he and his ship's crew formed a welcome change in the limited dietary of the exultant native. Mr. Barbot, who knew them well, feelingly remarks, "it is from the bloody tempers of these brutes that the Portuguese gave them the name of Malagens for they eat human flesh," and he cites how "recently they have massacred a great number of Portuguese, Dutch and English, who came for provisions and water, not thinking of any treachery, and not many years since, (that is to say, in 1677) an English ship lost three of its men; a Hollander fourteen; and, in 1678, a Portuguese, nine, of whom nothing was ever heard since."

From Cape Palmas until you are past the mouth of the Taka River (St. Andrew) the coast is low. Then comes the Cape of the Little Strand (Caboda Prazuba), now called, I think, Price's Point. To the east of this you will see ranges of dwarf red cliffs rising above the beach and gradually increasing in height until they attain their greatest in the face of Mount Bedford, where the cliff is 280 feet high. The Portuguese called these Barreira Vermelhas; the French, Kalazis Rouges; and the Dutch, Roode Kliftin, all meaning Red Cliffs. The sand at their feet is strewn with boulders, and the whole country round here looks fascinating and interesting. I regret never having had an opportunity of seeing whether those cliffs had fossils on them, for they seem to me so like those beloved red cliffs of mine in Kacongo which have. The investigation, however, of such makes of Africa is messy. Those Kacongo cliffs were of a sort of red clay that took on a greasy slipperiness when they were wet, which they frequently were on account of the little springs of water that came through their faces. When pottering about them, after having had my suspicions lulled by twenty or thirty yards of crumbly dryness, I would ever and anon come across a water spring, and down I used to go—and lose nothing by it, going home in the evening time in what the local natives would have regarded as deep mourning for a large family—red clay being their sign thereof. The fossils I found in them were horizontally deposed layers of clam shells with regular intervals, or bands, of red clay, four or five feet across; between the layers some of the shell layers were 40 or more feet above the present beach level. Identical deposits of shell I also found far inland in Ka Congo, but that has nothing to do with the Ivory Coast.

Inland, near Drewin, on the Ivory Coast, you can see from the sea curious shaped low hills; the definite range of these near Drewin is called the Highland of Drewin; after this place they occur frequently close to the shore, usually isolated but now and again two or three together, like those called by sailors the Sisters. I am much interested in these peculiar-shaped hills that you see on the Ivory and Gold Coast, and again, far away down South, rising out of the Ouronuogou swamp, and have endeavoured to find out if any theories have been suggested as to their formation, but in vain. They look like great bubbles, and run from 300 to 2,000 feet.

The red cliffs end at Mount Bedford and the estuary of the Fresco River, and after passing this the coast is low until you reach what is now called the district of Lahu, a native sounding name, but really a corruption from its old French name La-Hoe or Hou.

You would not think, when looking at this bit of coast from the sea, that the strip of substantial brown sand beach is but a sort of viaduct, behind which lies a chain of stagnant lagoons. In the wet season, these stretches of dead water cut off the sand beach from the forest for as much as 40 miles and more.

Beyond Mount La-Hou on this sand strip there are many native villages—each village a crowded clump of huts, surrounded by a grove of coco palm trees, each tree belonging definitely to some native family or individual, and having its owner's particular mark on it, and each grove of palm trees slanting uniformly at a stiff angle, which gives you no cause to ask which is the prevailing wind here, for they tell you bright and clear, as they lean N.E., that the S.W. wind brought them up to do so.

Groves of coco palms are no favourites of mine. I don't like them. The trees are nice enough to look on, and nice enough to use in the divers ways you can use a coco-nut palm; but the noise of the breeze in their crowns keeps up a perpetual rattle with their hard leaves that sounds like heavy rain day and night, so that you feel you ought to live under an umbrella, and your mind gets worried about it when you are not looking after it with your common sense.

Then the natives are such a nuisance with coco-nuts. For a truly terrific kniff give me even in West Africa a sand beach with coco-nut palms and natives. You never get coco-nut palms without natives, because they won't grow out of sight of human habitation. I am told also that one coco will not grow alone; it must have another coco as well as human neighbours, so these things, of course, end in a grove. It's like keeping cats with no one to drown the kittens.

Well, the way the smell comes about in this affair is thus. The natives bury the coco-nuts in the sand, so as to get the fibre off them. They have buried nuts in that sand for ages before you arrive, and the nuts have rotted, and crabs have come to see what was going on, a thing crabs will do, and they have settled down here and died in their generations, and rotted too. The sandflies and all manner of creeping things have found that sort of district suits them, and have joined in, and the natives, who are great hands at fishing, have flung all the fish offal there, and there is usually a lagoon behind this sort of thing which contributes its particular aroma, and so between them the smell is a good one, even for West Africa.

The ancient geographers called this coast Ajanginal Æthiope, and the Dutch and French used to reckon it from Growe, where the Melaguetta Coast ends. Just east of Cape Palmas, to the Rio do Sweiro da Costa, where they counted the Gold Coast to begin, the Portuguese divided the coast thus. The Ivory, or, as the Dutchmen called it, the Tand Kust, from Gowe to Rio St. Andrew; the Malaguetta from St. Andrew to the Rio Lagos;[1] and the Quaqua from the Rio Lagos to Rio de Sweiro da Costa, which is just to the east of what is now called Assini.

It is undoubtedly one of the most interesting and nowadays least known bits of the coast of the Bight of Benin; but, taken altogether, with my small knowledge of it, I do not feel justified in recommending the Ivory Coast as either a sphere for emigration or a pleasure resort. Nevertheless, it is a very rich district naturally, and one of the most amusing features of West African trade you can see on a steamboat is to watch the shipping of timber therefrom.

This region of the Bight of Benin is one of enormous timber wealth, and the development of this of late years has been great, adding the name of Timber Ports to the many other names this particular bit of West Africa bears, the Timber Ports being the main ports of the French Ivory Coast, and the English port of Axim on the Gold Coast.

The best way to watch the working of this industry is to stay on board the steamer; if by chance you go on shore when this shipping of mahogany is going on you may be expected to help, or get out of the way, which is hot work, or difficult. The last time I was in Africa we on the ——— shipped 170 enormous bulks of timber. These logs run on an average 20 to 30 feet long and 3 to 4 feet in diameter. They are towed from the beach to the vessel behind the surf boats, seven and eight at a time, tied together by a rope running through rings called dogs, which are driven into the end of each log, and when alongside, the rope from the donkey engine crane is dropped overboard, and passed round the log by the negroes swimming about in the water regardless of sharks and as agile as fish. Then, with much uproar and advice, the huge logs are slowly heaved on board, and either deposited on the deck or forthwith swung over the hatch and lowered down. It is almost needless to remark that, with the usual foresight of men, the hatch is of a size unsuited to the log, and therefore, as it hangs suspended, a chorus of counsel surges up from below and from all sides.

The officer in command on on this particular hatch presently shouts "Lower away," waving his hand gracefully from the wrist as though he were practising for piano playing, but really to guide Shoo Fly, who is driving the donkey engine. The tremendous log hovers over the hatch, and then gradually, "softly, softly," as Shoo Fly would say, disappears into the bowels of the ship, until a heterogeneous yell in English and Kru warns the trained intelligence that it is low enough, or more probably too low. "Heave a link!" shouts the officer, and Shoo Fly and the donkey engine heaveth. Then the official hand waves, and the crane swings round with a whiddle, whiddle, and there is a moment's pause, the rope strains, and groans, and waits, and as soon as the most important and valuable people on board, such as the Captain, the Doctor, and myself, are within its reach to give advice, and look down the hatch to see what is going on, that rope likes to break and comes clawing at us a mass of bent and broken wire, and as we scatter, the great log goes with a crash into the hold. Fortunately, the particular log I remember as indulging in this catastrophe did not go through the ship's bottom, as I confidently expected it had at the time, nor was any one killed, such a batch of miraculous escapes occurring for the benefit of the officer and men below as can only be reasonably accounted for by their having expected this sort of thing to happen.

Quaint are the ways of mariners at times. That time they took on quantities of great logs at the main gangway, well knowing that they would have to go down the hatch aft, and that this would entail hauling them along the narrow alley ways. This process was effected by rigging the steam winches aft, then two sharp hooks connected together by a chain at the end of the wire hawser were fixed into the head of the log, and the word passed "Haul away," water being thrown on the deck to make the logs slip easier over it, and billets of wood put underneath the log with the same intention, and the added hope of saving the deck from being torn by the rough hewn, hard monster.

Now there are two superstitions rife regarding this affair, The first is, that if you hitch the hooks lightly into each side of the log's head and then haul hard, the weight of the log will cause the hooks to get firmly and safely embedded in it. The second is, that the said weight will infallibly keep the billets under it in due position.

Nothing short of getting himself completely and permanently killed shakes the mariner's faith in these notions. What often happens is this. When the strain is at its highest the hooks slip out of the wood, and try and scalp any one that's handy, and now and again they succeed. There was a man helping that day at Axim whom the Doctor said had only last voyage fell a victim to the hooks; they slipped out of the head of the log and played round his own, laying it open to the bone at the back, cutting him over the ears and across the forehead, and if that man had not had a phenomenally thick skull he must have died. But no, there he was on this voyage as busy as ever with the timber, close to those hooks, and evidently with his superstitious trust in the invariable embedding of hooks in timber unabated one fraction.

Sometimes the performance is varied by the hauling rope itself parting and going up the alley way like a boa constrictor in a fit, whisking up black passengers and boxes full of screaming parrots in its path from places they had placed themselves, or been placed in, well out of its legitimate line of march. But the day it succeeds in clawing hold of and upsetting the cook's grease tub, which lives in the alley-way, that is the day of horror for the First officer and the inauguration of a period of ardent holystoning for his minions.

Should, however, the broken rope fail to find, as the fox-hunters would say, in the alley-way, it flings itself in a passionate embrace round the person of the donkey engine aft, and gives severe trouble there. The mariners, with an admirable faith and patience, untwine it, talking seriously to it meanwhile, and then fix it up again, may be with more care, and the shout, "Heave away!"—goes forth again; the rope groans and creaks, the hooks go in well on either side of the log, and off it moves once more with a graceful, dignified glide towards its destination. The Bo'sun and Chips with their eyes on the man at the winch, and let us hope their thoughts employed in the penitential contemplation of their past sins, so as to be ready for the consequences likely to arise for them if the rope parts again, do not observe the little white note—underbill—as a German would call it, which is getting nearer and nearer the end of the log, which has stuck to the deck. In a few moments the log is off it, and down on Chips' toes, who returns thanks with great spontaneity, in language more powerful then select. The Bo'sun yells, "Avast heaving, there!" and several other things, while his assistant Kruboys, chattering like a rookery when an old lady's pet parrot has just joined it, get crowbars and raise up the timber, and the Carpenter is a free man again, and the little white billet reinstated. "Haul away," roars the Bo'sun, "Abadeo Na nu de um oro de Kri Kri," join in the hoarse-voiced Kruboys, "Ji na oi," answers the excited Shoo Fly, and off goes that log again. The particular log whose goings on I am chronicling slewed round at this juncture with the force of a Roman battering ram, drove in the panel of my particular cabin, causing all sorts of bottles and things inside to cast themselves on the floor and smash, whereby I, going in after dark, got cut. But no matter, that log, one of the classic sized logs, was in the end safely got up the alley-way and duly stowed among its companions. For let West Africa send what it may, be it never so large or so difficult, be he never so ill-provided with tackle to deal with it, the West Coast mariner will have that thing on board, and ship it—all honour to his determination and ability.

The varieties of timber chiefly exported from the West African timber ports are Oldfieldia Africana, of splendid size and texture, commonly called mahogany, but really teak, Bar and Camwood and Ebony. Bar and Cam are dye-woods, and, before the Anilines came in these woods were in great request; invaluable they were for giving the dull rich red to bandana handkerchiefs and the warm brown tints to tweed stuffs. Camwood was once popular with cabinet makers and wood-turners here, but of late years it has only come into this market in roots or twisty bits—all the better these for dyeing, but not for working up, and so it has fallen out of demand among cabinet makers in spite of its beautiful grain and fine colour, a pinky yellow when fresh cut, deepening rapidly on exposure to the air into a rich, dark red brown. Amongst old Spanish furniture you will find things made from Cam-wood that are a joy to the eye. There has been some confusion as to whether Bar and Camwood are identical—merely a matter of age in the same tree or no—but I have seen the natives cutting both these timbers, and they are quite different trees in the look of them, as any one would expect from seeing a billet of Bar and one of Cam; the former is a light porous wood and orange colour when fresh cut, while 500 billets of Bar and only 150 to 200 of Cam go to the ton.

There are many signs of increasing enterprise in the West African timber trade, but so far this form of wealth has barely been touched, so vast are the West African forests and so varied the trees therein. At present it, like most West African industries, is fearfully handicapped by the deadly climate, the inferiority and expensiveness of labour, and the difficulties of transport.

At present it is useless to fell a tree, be it ever so fine, if it is growing at any distance from a river down which you can float it to the sea beach, for it would be impossible to drag it far through the Liane-tangled West African forest.

Indeed, it is no end of a job to drag a decent-sized log even two hundred yards or so to a river. The way it is done is this. When felling the tree you arrange that its head shall fall away from the river, then trim off the rough stuff and hew the heavy end to a rough point, so that when the boys are pully-hauling down the slope—you must have a slope—to the bank, it may not only be able to pierce the opposing undergrowth spearwise more easily than if its end were flat or jagged, but also by the fact of its own weight it may help their exertions.

I have seen one or two grand scenes on the Ogowé with trees felled on steep mountain sides, wherein you had only got to arrange these circumstances, start your log on its downward course to the river, get out of the fair way of it, and leave the rest to gravity, which carried things through in grand style, with a crashing rush and a glorious splash into the river. You had, of course, to take care you had a clear bank and not one fringed with dead-trees, into which your mighty spear would embed itself and also to have a canoe load of energetic people to get hold of the log and keep it out of the current of that lively Ogowé river, or it would go off to Kama Country express. But this work on timber was far easier than that on the Gold or Ivory Coasts, whence most timber comes to Europe, and where the make of the country does not give you so fully the assistance of steep gradients.

After what I have told you about the behaviour of these great baulks on board ship you will not imagine that the log behaves well during its journey on land. Indeed, my belief in the immorality of inanimate nature has been much strengthened by observing the conduct of African timber. Nor am I alone in judging it harshly, for an American missionary once said to me, "Ah! it will be a grand day for Africa when we have driven out all the heathen devils; they are everywhere, not only in graven images, but just universally scattered around." The remark was made on the occasion of a floor that had been laid down by a mission carpenter coming up on its own account, as native timber floors laid down by native carpenters customarily come, though the native carpenter lays Norway boards well enough.

When, after much toil and tribulation and uproar, the log has been got down to the river and floated, iron rings are driven into it, and it is branded with its owner's mark. Then the owner does not worry himself much about it for a month or so, but lets it float its way down and soak, and generally lazy about until he gets together sufficient of its kind to make a shipment.

One of the many strange and curious things they told me of on the West Coast was that old idea that hydrophobia is introduced into Europe by means of these logs. There is, they say, on the West Coast of Africa a peculiarly venomous scorpion that makes its home on the logs while they are floating in the river, three-parts submerged on account of weight, and the other part most delightfully damp and cool to the scorpion's mind. When the logs get shipped frequently the scorpion gets shipped too, and subsequently comes out in the hold and bites the resident rats. So far I accept this statement fully, for I have seen more than enough rats and scorpions in the hold, and the West Coast scorpions are particularly venomous, but feeling that in these days it is the duty of every one to keep their belief for religious purposes, I cannot go on and in a whole souled way believe that the dogs of Liverpool, Havre, Hamburg, and Marseilles worry the said rats when they arrive in dock, and, getting bitten by them, breed rabies.

Nevertheless, I do not interrupt and say, "Stuff," because if you do this to the old coaster he only offers to fight you, or see you shrivelled, or bet you half-a-crown, or in some other time-honoured way demonstrate the truth of his assertion, and he will, moreover, go on and say there is more hydrophobia in the aforesaid towns than elsewhere, and as the chances are you have not got hydrophobia statistics with you, you are lost. Besides, it's very unkind and unnecessary to make a West Coaster go and say or do things which will only make things harder for him in the time "to come," and anyhow if you are of a cautious, nervous disposition you had better search your bunk for scorpions, before turning in, when you are on a vessel that has got timber on board, and the chances are that your labours will be rewarded by discovering specimens of this interesting animal.

Scorpions and centipedes are inferior in worrying power to driver ants, but they are a feature in Coast life, particularly in places—Cameroons, for example. If you see a man who seems to you to have a morbid caution in the method of dealing with his hat or folded dinner napkin, judge him not harshly, for the chances are he is from Cameroon, where there are scorpions—scorpions of great magnitude and tough constitutions, as was demonstrated by a little affair up here that occurred in a family I know.

The inhabitants of the French Ivory Coast are an exceedingly industrious and enterprising set of people in commercial matters, and the export and import trade is computed by a recent French authority at ten million francs per annum. No official computation, however, of the trade of a Coast district is correct, for reasons I will not enter into now.

The native coinage equivalent here is the manilla—a bracelet in a state of sinking into a more conventional token. These manillas are made of an alloy of copper and pewter, manufactured mainly at Birmingham and Nantes, the individual value being from 20 to 25 centimes.

Changes for the worse as far as English trade is concerned have passed over the trade of the Ivory Coast recently, but the way, even in my time, trade was carried on was thus. The native traders deal with the captains of the English sailing vessels and the French factories, buying palm oil and kernels from the bush people with merchandise, and selling it to the native or foreign shippers. They get paid in manillas, which they can, when they wish, get changed again into merchandise either at the factory or on the trading ship. The manilla is, therefore, a kind of bank for the black trader, a something he can put his wealth into when he wants to store it for a time.

They have a singular system of commercial correspondence between the villages on the beach and the villages on the other side of the great lagoon that separates it from the mainland. Each village on the shore has its particular village on the other side of the lagoon, thus Alindja Badon is the interior commercial centre for Grand Jack on the beach, Abia for Anamaquoa, or Half Jack, and so on. Anamaquoa is only separated from its sister village by a little lagoon that is fordable, but the other towns have to communicate by means of canoes.

Grand Bassam, Assini, and Half Jack are the most important places on the Ivory Coast. The main portion of the first-named town is out of sight from seaboard, being some five miles up the Costa River, and all you can see on the beach are two large but lonesome-looking factories. Half Jack, Jack a Jack, or Anamaquoa—there is nothing like having plenty of names for one place in West Africa, because it leads people at home who don't know the joke to think there is more of you than there naturally is—gives its name to the bit of coast from Cape Palmas to Grand Bassam, this coast being called the Half Jack, or quite as often the Bristol Coast, and for many years it was the main point of call for the Guineamen, old-fashioned sailing vessels which worked the Bristol trade in the Bights.

This trade was established during the last century by Mr. Henry King, of Bristol, for supplying labour to the West Indies, and was further developed by his two sons, Richard, who hated men-o'-war like a quaker, and William who loved science, both very worthy gentlemen. After their time up till when I was first on the Coast, this firm carried on trade both on the Bristol Coast and down in Cameroon, which in old days bore the name of Little Bristol-in-Hell, but now the trade is in other hands.

According to Captain Binger, there are now about 30 sailing ships still working the Ivory Coast trade, two of them the property of an energetic American captain, but the greater part belonging to Bristol. Their voyage out from Bristol varies from 60 to 90 days, according as you get through the Horse latitudes—so-called from the number of horses that used to die in this region of calms when the sailing vessels bringing them across from South America lay week out and week in short alike of wind and water.

In old days, when the Bristol ship got to the Coast she would call at the first village on it. Then the native chiefs and head men would come on board and haggle with the captain as to the quantity of goods he would let them have on trust, they covenanting to bring in exchange for them in a given time a certain number of slaves or so much produce. This arrangement being made, off sailed the Guineaman to his next village, where a similar game took place all the way down Coast to Grand Bassam.

When she had paid out the trust goods to the last village, she would stand out to sea and work back to her first village of call on the Bristol Coast to pick up the promised produce, this arrangement giving the native traders time to collect it. In nine cases out of ten, however, it was not ready for her, so on she went to the next. By this time the Guineaman would present the spectacle of a farmhouse that had gone mad, grown masts, and run away to sea; for the decks were protected from the burning sun by a well-built thatch roof, and she lounged along heavy with the rank sea growth of these seas. Sometimes she would be unroofed by a tornado, sometimes seized by a pirate parasitic on the Guinea trade, but barring these interruptions to business she called regularly on her creditors, from some getting the promised payment, from others part of it, from others again only the renewal of the promise, and then when she had again reached her last point of call put out to sea once more and worked back again to the first creditor village. In those days she kept at this weary round until she got in all her debts, a process that often took her four or five years, and cost the lives of half her crew from fever, and then her consorts drafted a man or so on board her and kept her going until she was full enough of pepper, gold, gum, ivory, and native gods to sail for Bristol. There, when the Guineaman came in, were grand doings for the small boys, what with parrots, oranges, bananas, &c., but sad times for most of those whose relatives and friends had left Bristol on her.

In much the same way, and with much the same risks, the Bristol Coast trade goes on now, only there is little of it left, owing to the French system of suppressing trade. Palm oil is the modern equivalent to slaves, and just as in old days the former were transhipped from the coasting Guineamen to the transatlantic slavers, so now the palm oil is shipped off on to the homeward bound African steamers, while, as for the joys and sorrows, century-change affects them not. So long as Western Africa remains the deadliest region on earth there will be joy over those who come up out of it; heartache and anxiety over those who are down there fighting as men fought of old for those things worth the fighting, God, Glory and Gold; and grief over those who are dead among all of us at home who are ill-advised enough to really care for men who have the pluck to go there.

During the smoke season when dense fogs hang over the Bight of Benin, the Bristol ships get very considerably sworn at by the steamers. They have letters for them, and they want oil off them; between ourselves, they want oil off every created thing, and the Bristol boat is not easy to find. So the steamer goes dodging and fumbling about after her, swearing softly about wasting coal all the time, and more harshly still when he finds he has picked up the wrong Guineaman, only modified if she has stuff to send home, stuff which he conjures the Bristol captain by the love he bears him to keep, and ship by him when he is on his way home from windward ports, or to let him have forthwith.

Sometimes the Bristolman will signal to a passing steamer for a doctor. The doctors of the African and British African boats are much thought of all down the Coast, and are only second in importance to the doctor on board a telegraph ship, who, being a rare specimen, is regarded as, ipso facto, more gifted, so that people will save up their ailments for the telegraph ship's medical man, which is not a bad practice, as it leads commonly to their getting over those ailments one way or the other by the time the telegraph ship arives. It is reported that one day one of the Bristolmen ran up an urgent signal to a passing mail steamer for a doctor, and the captain thereof ran up a signal of assent, and the doctor went below to get his medicines ready. Meanwhile, instead of displaying a patient gratitude, the Bristolman signalled "Repeat signal." "Give it'em again," said the steamboat captain, "those Bristolmen ain't got no Board schools." Still the Bristolman kept bothering, running up her original signal, and in due course off went the doctor to her in the gig. When he returned his captain asked him, saying, "Pills, are they all mad on board that vessel or merely drunk as usual?" "Well," says the doctor, "that's curious, for it's the very same question Captain N. has asked me about you. He is very anxious about your mental health, and wants to know why you keep on signalling 'Haul to, or I will fire into you,'" and the story goes that an investigation of the code and the steamer's signal supported the Bristolman's reading, and the subject was dropped in steam circles.

Although the Bristolmen do not carry doctors, they are provided with grand medicine chests, the supply of medicines in West Africa being frequently in the inverse ratio with the ability to administer them advantageously.

Inside the lid of these medicine chests is a printed paper of instructions, each drug having a number before its name, and a hint as to the proper dose after it. Thus, we will say, for example, 1 was jalap; 2, calomel; 3, croton oil; and 4, quinine. Once upon a time there was a Bristol captain, as good a man as need be and with a fine head on him for figures. Some of his crew were smitten with fever when he was out of number 4, so he argues that 2 and 2 are 4 all the world over, but being short of 2, it being a popular drug, he further argues 3 and 1 make 4 as well, and the dose of 4 being so much he makes that dose up out of jalap and croton oil. Some of the patients survived; at least, a man I met claimed to have done so. His report is not altogether reproducible in full, but, on the whole, the results of the treatment went more towards demonstrating the danger of importing raw abstract truths into everyday affairs than to encouraging one to repeat the experiment of arithmetical therapeutics.

- ↑ No connection with the Colony of Lagos.