While Caroline Was Growing/A Watch in the Night

VIII

A WATCH IN THE NIGHT

The village clock boomed out the first strokes of eleven. Solemn and mellow, the waves of sound flowed over the sleeping streets; the aftertones vibrated plaintively. Caroline stirred restlessly, tossing off the sheet and muttering in her dreams. The tears had dried on her hot cheeks; her brows were still knitted.

"Four! Five! Six!" the big bell tolled.

Caroline sat up in bed and dropped her bare, pink legs over the edge. Her eyes were open now, but set in a fixed, unseeing stare.

"Seven! Eight!"

She fumbled with her toes for her leather barefoot sandals and slipped her feet under the ankle straps.

"Nine! Ten!" moaned the bell.

She moved forward, vaguely, in the broad path of moonlight that poured through the wide-open window, and ran her hands like a blind girl over the warm sill, lifting her knee to its level.

"Eleven!"

Before the murmuring aftertones had lost themselves in the night, Caroline was out of the window. She stole lightly along the tin roof, warm yet with the first intense heat of June, dropped easily to the level of the kitchen-ell, and, slipping down onto the massive trunk of the old wistaria, fitted accustomed feet into its curled niches and clambered down among the warm, fragrant clusters. Steeped in the full moon, it sent out its cloying perfume like a visible cloud; her white nightgown glistened ghostlike through the leaves.

She paused a moment in the shadow of the vine, and a great tawny cat, his orange markings distinct in the moonlight, stole to her, brushing against her bare ankles caressingly. As he curled and uncurled his soft tail about her little feet, a sudden impulse caught her, and she started swiftly through the wide backyard, bending to a broken gap in the privet hedge, cutting diagonally across the neighboring grounds, and emerging into a pleasant country road on the outskirts of the little village, with sleeping houses sprinkled along its length, well back, mostly, from its edge, showing here and there a light.

She struck into the soft, dusty road at a quick, swinging pace, the fruit of much walking, and the big yellow cat pattered at her side.

The night was almost windless; sweet, nameless odors poured up from the heated summer soil; the shadows of the grasses were outlined like Japanese pictures on the white roadway. Except for the child and the cat, no living being moved, as far as the eye could see; only the burdocks and mulleins swayed almost imperceptibly with breezes so delicate that the leaf tips of the trees could not feel them.

A great white moth, blundering against a heavy thistle head, tumbled against Caroline's elbow and fluttered clumsily into her face. She started, blinked, drew a long breath, and woke with a frightened gasp. Before her stretched the pale, curving road; above her the spangled sky throbbed and glittered; the earth, drenched in moonlight, beautiful as all lovely creatures caught sleeping, breathed softly into her face and with every breath put courage into her heart.

She looked down and saw the yellow cat, stopping, with one lifted paw, his green, lamplike eyes fixed unwaveringly on hers.

"Why, it's you, Red Rufus!" she whispered, "when did we come here? I don't remember—"

A bat whirred by: the cat pricked his ears.

"I don't believe we're here at all, Red Rufus," she whispered again. "We're just dreaming—at least, I am. I s'pose you're only in my dream. If I was really here, I'd be frightened to death, prob'ly, but if it's just a dream, I think it's lovely. Let's go on. I never had a dream like this—it seems so real, doesn't it, Rufus?"

They went on aimlessly up the road. Quaint little night sounds began now to make themselves heard: now and then a drowsy twitter from the sleeping nests, now and then a distant owl hoot. A sudden gust of honeysuckle, so strong that it was like a friendly, fragrant body flung against her, halted her for a moment, and while she paused, sniffing ecstatically, the low murmur of voices caught her ear.

The honeysuckle ran riot over an old stone wall, followed an arching gateway at the foot of a winding path that led to a lighted house on a knoll above, and flung screening tendrils over an entwined pair that paused just inside the gate. The girl's white, loose sleeves fell back from her round arms as she flung them up about her tall lover's neck; his dark head bent low over hers, their lips met, and they hung entranced in the bowery archway.

For a moment Caroline watched them with frank curiosity. Then something woke and stirred in her, faint and vague, but alive now, and she turned away her eyes, blushing hot in the cool moonlight.

The soft tones of their good-night died into broken whispers; parted from his white lady, he started on for a few, irresolute steps, then flung about suddenly and walked back toward the house, after a low, happy protest. The cooing of some drowsy pigeons in the stable on the other side of the road carried on the lovers' language long after they were out of earshot, and confused itself with them in Caroline's mind.

She wandered on, intoxicated with the mild, spacious night, the dewy freedom of the fields, the delicious pressure of the warm, velvet air against her body. Red Rufus purred as he went, rejoicing with his vagabond comrade. Just how or when she began to know that she was not asleep, just why the knowledge did not alarm her, it would be hard to say. But when the truth came to her, the friendly, powdered stars had been above her long enough to accustom her to their winking; the tiny, tentative noises of the night had sounded in her ears till they comforted and reassured her; the vast and empty field stretches meant only freedom and exhilaration. In a sudden delirium of joy she slipped between the bars of a rolling meadow and ran at full speed down its long, grassy slope, her nightgown streaming behind her, her slender, childish legs white as ivory against the greenish-black all around her. Beside her bounded the great cat with shining, gemlike eyes. They rolled down the last reaches of the slope, and all the Milky Way wondered at them, but never a sound broke the solemn quiet of the night: the ecstasy was noiseless.

Her face buried in sweet clover, she panted, prone on the grass.

"Let's go right on, Rufus, and run away, and do just as we please!" she whispered to the nestling cat. "If I can't do like the boys do, I don't want to stay home—the fellows laugh at me! I'd rather be whipped than sent to bed like a girl. I won't be a young lady—I won't!"

Rufus purred approvingly.

"If I only had some trousers!" she mourned, softly; "a boy can do anything!"

Across the quiet night there cut a thin, shrill cry: a little, fretful pipe that brought instantly before the mind some hushed, white room with a shaded light and a tiny basket bed. Caroline sat up and stared about her: such cries did not come from open fields. Hardly a stone's throw from her there was a small knoll, and behind it what might have been a large, projecting boulder suddenly flashed into red light and showed itself for a dormer window; a cottage had evidently hidden behind the little hill. Curiously Caroline approached it and walked softly up the knoll.

Almost on the top she paused and peered into the unshaded window. These householders had no fear of peeping neighbors, for only the moon and the night moths found them out, and the simple bedroom was framed like some old naïve interior, realistic with the tremendous realism of the Great Artist.

The high, old-fashioned footboard of the bed faced the dormer window, and Caroline could see only the upper portion of the woman's figure as she leaned over a small crib beside her, her heavy dark hair falling across her cheek, and lifted up with careful slowness the tiny creature that wailed in it. Beside her, as he supported himself anxiously on his elbow, the broad chest and shoulders of her young husband rose above the screening footboard. The mother gazed hungrily at the doll-like, writhing object, passed her hand over its downy forehead, smiled with relief into its opening eyes, and gave it her breast.

Instantly the wail ceased. A slow, placid smile—and yet, not quite a smile—it was rather an elemental content, a gratified drifting into the warm current of the stream of this world's being—spread over the woman's face; the man's long arm wrapped around his wealth, at once protecting and defiant; his head flung back against the world, while his eyes studied humbly the mystery that he grasped. The night lamp behind them threw a halo around the mother and her child, and the great trinity of all times and all faiths gleamed immortal upon the canvas of the simple room—its only spectator a child.

In her, malleable to all the influences of the revealing night, fairly disembodied, in her detached and flitting presence, the scene woke dim, coiled memories of an infancy that stirred and pained her even as it left her forever, and frightened longing for the motherhood that life was holding for her. No longer an infant, not yet a woman, this creature that was both felt the helplessness of one, the yearning of the other, and as she pressed the nestling cat tightly to her little breast two great, eager tears slipped down her hot cheeks, and a gulping sob, half loneliness, half pure excitement, broke into the gentle stillness of the lighted room.

"Who's there?"

The man's voice rang like a sudden pistol shot in the night; before Caroline's fascinated gaze the gleaming, softly colored picture faded and vanished into the engulfing darkness, as the lamp went out and a dark, scudding mackerel cloud flew over the moon. Instinctively she fled softly down the knoll, instinctively she dropped behind a bush at the bottom. She heard the rattle of the window pane as the man pushed himself half out of the window; she heard him call back to the waiting room behind him!

"It's a cat, dear—I saw it, plain. It's pretty bright out here. But I thought I saw something white beside it, too. I guess I'll take a look around outside."

There was a sound of movement behind the window, and, caught in an ecstasy of terror, Caroline turned at right angles from the fields and ran to the road that gleamed white, far on the other side of the cottage. Panting, she won it, crossed it, and fairly safe behind the low growth of wayside brushes that fringed its other side, she dashed along, farther and farther from the cottage, more and more frightened with every gasping breath.

On and on she flew, light as a skimming leaf in the wind, the cat bounding in easy, flexible curves beside her. Now a little brown cottage in its plot of land sent them into the road for a moment; now some tiny pond, a mirror for the sprinkled heavens, broke into their course, and they skirted it more slowly, peering continuously into its jeweled depths. With them their hurrying shadows, black on the road, fainter on the grass, fled ceaselessly, hardly more quiet than they. A very intoxication of fear, a panic terror almost delicious, drove Caroline through the night, though after a while she ran more slowly. Utterly ignorant of where she was, reckless of where she might go, she swung along under the streaming moon, no white moth or whispering leaf more wholly a part of the night than she.

Whatever idea of going back she might have had was lost long ago; however little she might have meant to range so far, she was now beyond any turning. No wood creature, no skipping faun or startled dryad dancing under the moon could have belonged more utterly than she to the fragrant, mysterious world around her. The bright, bustling life of every day, its clatter of food and drink, its smarts and fatigues, its settled routine of work and play, all seemed as far behind her as some old tale of another life, half forgotten now.

Just as her pace subsided into a little skipping trot, a thick hedge sprang up across their path, driving them into the road, and continued, stiff and tall, along its edge. The pure pleasure of conquering its prickly stiffness sent Caroline through it, tearing one sleeve from her nightgown and dragging a great rent in one side of it. Emerging into a magnificent sweep of clipped turf, where wide, leafy boughs spread dappled moon shadows, they made for a whispering, clucking fountain that threw a diamond column straight toward the stars, only to break at the top into a beaded mist and clink musically back to its marble basin. Its rhythmic tinkle, the four ball-shaped box trees at either corner, the carved whiteness of the marble basin, and the massive pillar-fronted stone house beyond it, all spread a glamour of fairyland and foreign courts. Caroline bowed gravely to the cat, and, seizing his feathery paws, danced, bowing and posturing, in a bewitched abandon around the tinkling, glistening fountain. The plumy tail of Red Rufus flew behind him as he twirled, his little feet pattered furiously after Caroline's twinkling sandals. Stooping over the fountain, she threw a silvery handful high in the air and ran to catch it on her head.

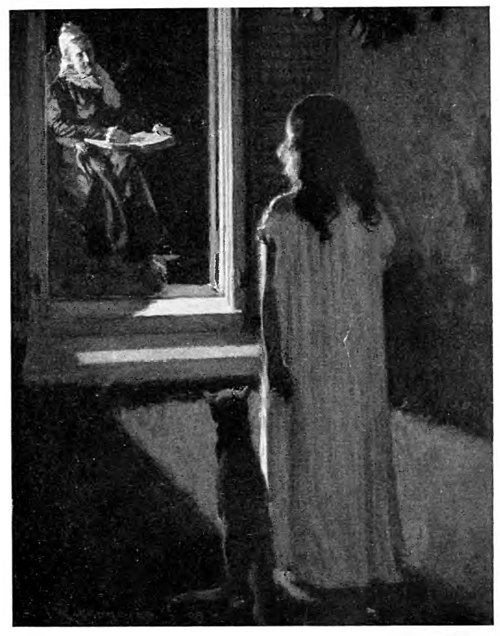

As she stood at last, panting and dazed with her mad circling, she was aware of the low murmur of a voice, rising and falling in a steady measure, reaching out of the dim bulk of the great house, dark and sunk in sleep before her. For a moment a chill fear struck to the bottom of her little heart: was some weird spell aimed at her, some malignant eye spying on her? She stood frozen to the spot, the tiny drops of sweat cooling on her forehead, while the droning sounded in her ears. Then, out of the very core of her terror, some inexplicable impulse urged her on to face it, and she crept, step by step, the cat tight in her nervous grasp, around the corner of the great house, toward the sound.

This corner was a wing, set at right angles to the main building, and as she rounded it she found herself at the edge of an inner court. In the opposite wing, looking straight across the court, was a lighted room with a long French window opening directly on the shaven turf, and in the center of this window there sat in a high, carved chair a very old woman. She was carefully dressed in deep black, with pure white ruffles at her neck and around her shrunken wrists, and a lace cap on her thin, white hair. Her feet were on a carved foot-stool, and a quaint silver lamp, set on a slender table at her side, threw a stream of light across the court. Her face, lined with countless wrinkles, was bent upon a large book in her lap; from its pages she read in a low, steady voice—the passionless, almost terrifying voice of great and weary age:

"Lord, thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations.

"Before the mountains were brought forth, or ever thou hast formed the earth and the world, even from everlasting to everlasting thou art God."

Across the court was a lighted room with a long French window, and in the center of this window there sat in a high, carved chair a very old woman.

"For a thousand years in thy sight are but as yesterday when it is past, and as a watch in the night."

The grave, steady voice flowed out and mingled with the silver lamplight; the marble sill of the long window was white like the sill of a tomb.

"We spend our years as a tale that is told.

"The days of our years are threescore years and ten; and if by reason of strength they be fourscore years, yet is their strength labor and sorrow; for it is soon cut off, and we fly away."

The hot excitement of this magic night cooled slowly; over Caroline's bubbling spirit there fell a mild, strange calm. A breath from the very caverns of the infinite stole out along the path of that silver lamp, and in the grave, surrendered voice there sounded for the child upon life's threshold echoes of the final tolling.

Entranced by the measured cadences, Caroline stepped forward unconsciously and stood, white against the gray stone, full in the path of the lamp. The heavy, wrinkled lids raised themselves from the deep-set eyes, and the aged reader gazed calmly at the little figure across the court. The withered old hands clasped each other.

"Jemmy! O Jemmy!"

Caroline never moved.

"It is you, Jemmy!"

The faded eyes devoured the little white figure.

"I thought you'd never come, Jemmy—but I knew they'd send you. I'm all ready. Don't you think I'm afraid, Jemmy: I'm eighty-four years old, and I want to go."

Caroline hardly breathed; a nameless awe held her motionless and silent.

"You see, I don't sleep much any more, Jemmy," the old, toneless voice went on, "and hardly any at night. They're very kind, all of them, but I'm—I'm eighty-four years old, and I want to go."

The ivory tulips gleamed under the stars; the silver lamp, burned lower and lower: its oil was nearly gone.

"And you brought your yellow kitty, too, Jemmy! To think of that! Did they think I wouldn't know my baby? It's only fifty years, ... shall I come now, Jemmy?"

The silver lamp went out. In the starlight Caroline saw the lace cap droop forward, as the the old woman's head settled gently on her breast. Her hands lay clasped on the great volume; her deep-set eyes were closed. She read no more from the book, and the child, awed and sober, stole like a shadow behind the gray wall and left the quiet figure in the carved chair.

Her feet fell into a tiny graveled path, and she drifted aimlessly along it, musing on the meaning of what she had heard. Almost she had persuaded herself that the gray stone building was an enchanted palace, and herself a fairy messenger sent to break the spell, when the delight of pushing through a tiny turnstile and finding a running brook with a waterfall in it close at hand, drove everything else from her mind. The grounds had completely changed their character by now: the turnstile marked the end of cultivation, and the little path, no longer graveled, wound through the wild woodland. Here and there a boulder blocked the way; the undergrowth became dense; great clumps of fern and rhododendron sent out their heavy, rank odors. Now and again the spicy scent of warm pines and cedars prepared the ear for the gentle, ceaseless rustle of their stiff foliage; little scufflings and chitterings at the ground level told of wood-people wakened by the presence of Red Rufus.

A strange whitish bulk that glimmered through the thinning foreground, too big for even a big boulder, too symmetrical and quiet for a waterfall, tempted Caroline on, and she pressed forward hastily, lost in speculation, when a sudden odor foreign to the woods stopped her short at the very edge of a little glade, and she paused, sniffing curiously.

A man, bareheaded, with grizzled curly hair, turned suddenly, not ten feet from her, and stared dumfounded at her, his twisted, brown cigar an inch from his lips.

The torn-out sleeve of her nightgown had bared one side to her waist: the great rent that slit the lower half of the garment left one slender leg uncovered above her white knee. A spray of wild azalea wreathed her dark tumbled hair, and Rufus, his plumy tail curled around her feet in the shadow, and his green eyes flaming, might have been a baby panther. She leaned one hand on the rough bark of a chestnut and gazed with startled eyes at the man; it seemed that the forest must swallow her at a breath from a human throat.

He lifted one hand and pinched the back of the other with it till his face contorted with the pain.

"Then there are such things!" he said softly; "well, why not?"

He moved forward almost imperceptibly.

"If I were younger, I should know you were not possible," he muttered, "but now I know that I have never doubted you—really."

Again he took a small step. Caroline, paralyzed with fear and embarrassment, for she thought he was merely teasing her a little before he punished her—his pleasant, low voice and whimsical manners brought her back suddenly to the ordinary world and the stern facts of her escapade—shivered slightly, but did not attempt flight.

"It was this extraordinary night that brought you out, of course," he went on, again slightly shortening the distance between them, "you and the little cub. It was a moon out of five thousand, I admit. Do you live in that chestnut?"

With a sudden agile bound he covered the space between them and seized her by the shoulder.

"Aha!" he cried, "I have—good heavens, it is a child!"

"Of course I am—I'm Caroline," she murmured writhing under his grasp.

He pulled her out into the little glade.

"Oh! you're Caroline, are you?" he repeated, thoughtfully; "dear me, you gave me quite a turn, Caroline. Where did you come from—the big house?"

"I came from a long way," she said briefly. "I was—I was taking a walk. Where do you live? Don't you ever to go bed?"

The man chuckled.

"I have been feeling adventures in my bones all day," he said, "and here they are; a child and a cat. If you will come with me, Mademoiselle, I will show you where I live."

He led the way gravely to the dim, white object, and Caroline perceived it to be a tent, pitched by the side of a spring that poured through a tiny pipe set into the rock. The tent flap was tied back, and she saw inside it a narrow cot, covered with a coarse blue blanket, a roughly made table, spread with a game of solitaire, and a small leather trunk. On the further side of the tent there smoked, in a rude, improvised oven of stones, a dying fire. Above it, under a shelf nailed to the tree, hung a few simple utensils; two or three large stumps had been hacked into the semblance of seats.

To one of these stumps the man led Caroline, and, seating her, he turned to the shelf above the fire and fumbled among the pots and pans there, producing finally a buttered roll, a piece of maple sugar, and a small fruit tart.

"You must be hungry," he said simply, and Caroline ate greedily. After he had brought her a tin cup of the spring water, he selected a brown pipe from a half dozen on the shelf and began filling it from a leather pouch that hung on the tree.

"Now let's hear all about it," he said easily.

"I am running away," said Caroline abruptly. At that moment it really seemed that she had planned her flight from the hour that left her, tear-stained and disgraced, in her little bed.

"They didn't treat you well?" he suggested, picking out a red ember from the coals on the point of a knife and applying it to the pipe.

"I'm not to wear my knickers any more," Caroline said, with a gulp, "and my bathing suit has to have a skirt. I've got to stop p-playing with the b-boys—so much, that is," she added, honestly.

The man turned his head slightly.

"That seems hard," he said; "what's the reason?"

"I'm 'most twelve," said Caroline; "you have to be a young lady, then."

"I see," the man said. He looked at her thoughtfully. "I suppose you would look larger in more clothes," he added.

"That's it," she assured him, "I do. That's just it."

"And so you expect to avoid all this by running away?" he asked, settling into his own stump seat. "I am afraid you can't do it."

Caroline set her teeth. He regarded her quizzically.

"See here," he went on, "I wish you'd take my advice in this matter."

They confronted each other in the starlight, a strange pair before the dying fire. The moon had gone, and the stars, though bright, seemed less solid and less certainly gold than before. A cool breeze swept through the wood and Caroline shivered in her torn nightdress. The man stepped into the tent and returned with a long army cloak. This he wrapped round her and resumed his seat, with Rufus on his knee.

"My name," he said, "is Peter. Everybody calls me that—just Peter. I don't know exactly why it is, but a lot of people—all over—have got into the way of taking my advice. Perhaps because I've knocked about all over the world more or less, and haven't got any wife or children or brothers and sisters of my own to advise, so I take it out on everybody else. Perhaps because I try to put myself in the other fellow's place before I advise him. Perhaps because I've had a little trouble of my own, here and there, and haven't forgotten it. Anyhow, I get used to talking things over."

A gentle stirring seemed to pass through the woods: the birds spoke softly back and forth, a squirrel chattered. Again that cool wind swept over the trees.

"Now, take it this week," the man went on, puffing steadily; "you wouldn't believe the people just about here who've asked for my advice. I usually camp up here for a week or so in the summer—the people who own the property like to have me here—and the first day I unpacked, up comes a nice girl—I used to make birch whistles for her mother—to tell me all about her young man. She brought me that spray of honeysuckle over the pipes—grows over the front gate. She wants to marry him before her father gets to like him, but she hates to run away. 'Would you advise me to, Peter?' she says. And I advised her to wait.

"Then there's my friend the blacksmith. He lives in a queer little house with dormer windows under a hill, just off the county road. He's got a new baby, and he was afraid it wouldn't pull through. He knew I'd seen a lot of babies—black and red and yellow—and he wanted my advice. 'Peter, what'll I do?' he says, 'what'll I do?'

"'Why, just wait, Harvey. He'll live. Just wait,' I told him."

Caroline listened with interest. He might have been talking to his equal in years, from his tone.

"Then, oddly enough," he continued, "here's my old friend in the big house up yonder—and she is old—and what do you think she's worried about? She's afraid she won't die! 'Oh, Peter,' she says to me—she's fond of me because I'm the same age as a little boy of hers that died—'it seems to me that I can't wait, Peter! What shall I do?' she says. And I tell her to wait. 'Dear old friend,' said I to her last night, 'it will come. It's bound to come. Just be patient.'"

He paused and knocked his pipe empty.

"Now, as to your case," he said, "I know how you feel. I'm sorry for you—by the Lord, I'm sorry for you! But what's the use of running away? You'll keep on growing up, you know. It's one of the things that doesn't stop. You can't beat the game by wearing knickers, you know. And then, there'd come a time when you'd want to quit, anyhow."

She shook her head.

"Really, you would," he assured her, persuasively. "They all do."

"That's what Uncle Joe says," she admitted, "and Aunt Edith. She changed her mind, she says—"

"Are you talking about Joe Holt?" Peter demanded.

"Yes—do you know him? He lives in a big white house with wistaria on the side," Caroline cried joyfully.

"I was a senior when he was a freshman," said Peter. "Then he's taken the Washburn house."

"Do you know Aunt Edith, too?" asked Caroline.

"Yes," said Peter, after a pause, "yes, I know Aunt Edith—or used to. But I didn't know she—they were up in this country. I haven't seen her—them for a good while. Does—does she sing yet?"

"Oh, yes, but not on the stage any more, you know," Caroline explained.

"I see. Does she sing, I wonder, a song about— Oh, something about 'my heart'?"

"'My heart's own heart,' you mean," Caroline said importantly; "yes, indeed. It's her encore song."

"I see," said Peter again.

He looked into the fire, and there was a long silence. After a while he shook his shoulders like a water-dog.

"Now, Caroline," he said briskly, "here's the way of this business. You can't wear knickers until you're one of the boys, and you can't be one of the boys until you wear knickers. Do you see? So you don't get anywhere."

Caroline looked puzzled. She was suddenly overcome with sleep, and the old familiar names and ways tasted of home and comfort to her soul.

"You're too nice to be a boy, Caroline," said Peter, leaning over her and brushing her azalea-crowned hair tenderly with his lips. "If you persist in this plan of running away to be a boy, some boy, growing up anxiously, somewhere, will never forgive you! Take my advice, and wait—will you? Say 'Yes, Peter.'"

"Yes, Peter," Caroline murmured, drowsily.

"Good girl! Then I'll take you home with my little donkey. I don't believe they've missed you yet. You've come four miles, though, you little gypsy!"

He disappeared behind the trees, and Caroline nodded. Later she woke sufficiently to find herself and Rufus on the blue blanket on the bottom of a little donkey cart; Peter stood by the gentle, long-eared head.

"Thank you, Peter," she murmured, half asleep, "and you'll see Aunt Edith, won't you?"

"I don't believe so," he said, very low. "Not yet. Tell her Peter brought you back. Just Peter. But he can't come yet. Get up, Jenny!"

They wound out by an old wood road. A cool spiciness flowed though the green aisles, and as the tiny donkey struck into a dog trot, the man striding easily at her head, a far-away cock crowed shrilly and the dawn gleamed white.