Women Wanted/Chapter 6

CHAPTER VI

The Open Door in Commerce

Something has just happened. A hidden hand has touched a secret spring. A closed door in a blank wall has opened. And one in the long cloak of authority seems to be standing at the threshold pleasantly beckoning the Lady to cross formerly forbidden portals.

For I feel like that, like a little girl living in a fairy tale that is turning true right before my eyes. This morning there has arrived in my mail a letter personally addressed to me from the New York University School of Commerce, Accounts and Finance. It announces that the entrance of the United States into the war has revolutionised American business. That hundreds of thousands of men off for the front are leaving behind them hundreds of thousands of vacancies. That commercial houses are facing a shortage of trained and capable assistants. That to fill the positions which are daily presenting themselves, women must enter business. That to give them the necessary training, this school offers no less than 142 courses from which they may make their preparation for executive positions of responsibility.

It is the first time that I and the League for Business Opportunities for Women to which I belong, have ever thus received a personal invitation to the wide open world of commerce. The League since its inception some five years ago has been alertly engaged in looking, as its name implies, for business opportunities for women. We have always been obliged to look pretty persistently for them. Never before have they been presented to us. Now, see, the way is clear, they tell us, right up the steeps of high finance.

The bursting bombs of war have done it. A ghastly Place aux Dames, it is in truth. But the stage is set. The cue is given. There is not even time to hesitate. Draughted, the long lines come on with steady tread. Now our battalions fall in step with the battalions of the Allies and the Central Powers. For English or Hun or French or Magyar or Russian or Serb or American, the woman movement is one like that. Through the same doorway of opportunity we all of us shall enter in. There are blood stains on the lintel, I know. But this door, for the first time set ajar, is the only way, it appears, between the past and the future. With the invitation from the New York School of Commerce on my desk before me, I too am at the threshold where the centuries meet. Down the vista that stretches before me, I look with long, long thoughts.

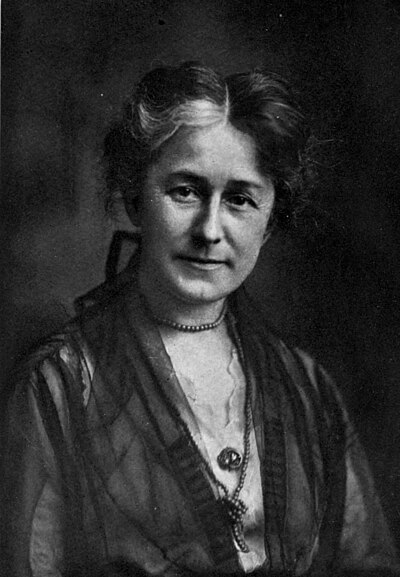

And once more, Cecile Bornozi somewhere in Europe is passing the sugar. In pursuit of food conservation, hotel waiters have a way of removing the sugar bowl to the dining room sideboard and thoughtfully forgetting to offer it a second time. And the Of the Financial Centre for Women in New York, who stands at the open door in commerce to usher in the women of America.

She is a type distinct from her predecessors in that old world of ours that is going up in battle smoke. Her brown hair is done in as coquettish a curl on her forehead, her eyes are as sparkling blue, her lips are as curving red as any girl's who used to have nothing to do but to dance the tango and pour afternoon tea. But her horizon has widened beyond the drawing room. Nor is she the business woman whom we have had with us for a generation. Why, the stenographer who takes my dictation is a business woman. But from her hand bag as another woman might produce a shopping list, Cecile Bornozi has just drawn forth a $50,000 bill of sale to her for a freight steamer.

She has just purchased it because of the increasing scarcity of tonnage in which to transport the fire brick that she is buying for the reconstruction of factory furnaces in the devastated districts of France. Yesterday she shipped 90 cwt. of oil boxes and bearings and 6 railway coal wagons. In the past few months she has sent over some 2000 railway wagons. Like this, during the past year, she has expended a million dollars for railway rolling stock that she rents to the French Government. She is specially commissioned by France for this undertaking, as her Commission Internationale de Ravitaillement spread in front of my breakfast roll shows to me and all of the Allies. A shipper has to have a license like this in these days. It is what secures for her her export permit from the London Board of Trade. Now she sets down her coffee cup and folds her newspaper and is off for India House in Kingsway where foregather other merchants who have confidential appointments with the War Office and the English Government. Upon her decisions to-day will depend so much more than the selection of a ribbon to match the blue of her eyes or the choice of the card to win at an afternoon bridge whist party. Her care and her forethought, her planning and her enterprise must outwit even the German submarines and get the goods across the English Channel to keep the transportation lines of a nation open for communication with the front. And there will be no superior at her elbow to tell her how.

"I like big ventures. I like to do things myself. I'd sell flowers on the curb before I'd consent to be any one's else employé," the new woman in commerce flashed back at me as she buttoned her coat collar and started out in a ten o'clock morning fog.

RISING TO THE NEW OCCASION

You see, it's like that. The big venture is the fascinating field that lies beyond humdrum directed routine. We have by now forgotten the stir that was created when perhaps thirty years ago the first woman walked into a business house to take her place at a typewriter desk. Let us not lose sight of the innovation of our own day that is about to command attention: the woman at the typewriter is rising. I think we shall see her take the chair before the mahogany desk in the president's office.

The Woman's Association of Commerce of America was recently organised at Chicago in a convention of business women gathered from cities from New York to Chicago. For the first time adequate training to fit a woman for real commercial responsibilities is beginning to be as freely offered as to men. Cecile Bornozi, widely known as the only railway woman in France, came by her commercial knowledge largely through instinct and inheritance. She gave up literature at the Sorbonne for it, because as the daughter of Philip Bornozi, from Constantinople, who supplied rolling stock to the railways of the Orient, France, and Belgium, the call to commerce was in her blood. But except for the few specially placed women like that, the way up in commerce before the year 1914 was not plain and easy. Now all over the world there are floating in on the morning mail invitations like the one that has just come to me from the New York University.

How much it means, I suppose no man can quite understand. Suppose you, sir, were going to attempt to talk glibly in terms of chiffon and voile and chambray and all the rest of those mystifying terms that tangle the tongue of a novice sent down the aisle of a department store with a sample in his lower left hand vest pocket to be properly matched—you'd feel, wouldn't you, that a course in this positively unknown tongue would be helpful in making yourself and your errand rightly understood. Just so. Now all unknown language is a handicap as is this one to you, which is quite familiar to every woman, for we learn to lisp in terms of our clothes. But on the other hand, there are commercial terms which you as a boy imbibed as naturally from your environment, which are to your sister a foreign tongue. We need the schools to teach it. And I am not sure but it is the schools now being set up by the women who have learned through their own experience that offer the surest interpretation of the way in these new paths in which women's feet are set to-day.

Just off from Central Park West in New York City, the Financial Centre for Women has been established in direct response to the war demand. Wall Street asked for it. Already 60 young women instructed in practical banking, investments, accountancy, and managerial duties have been sent out to fill responsible positions in the National Bank of Commerce, Morgan's, the Federal Reserve and over half a dozen other of the leading banks of New York City. These young women have been given an intimate working knowledge of such mysteries as stop payments and certified checks, gold imports, cumulative and preferred shares and all the intricacies of the market and the terms in which "the street" talks. In the room with the green cloth covered table, about which sit these future financiers and captains of industry in training, there is a blackboard. See the chalk marked diagram. By the routes mapped out in those white lines, they have brought furs from Russia, wheat from Canada, sugar from Hawaii. And all the money transactions involved have been properly put through. Thoroughly familiarised like this with international operations, there is more to learn for the making of a financier. I doubt if any but a woman would think to teach it. Miss Elizabeth Rachel Wylie, who directs the Financial Centre, recalls her classes from the wide world of affairs through which they circle the globe, for personal instruction. They have now the groundwork of the knowledge with which a business man is familiar. And Miss Wylie adds earnestly, impressively the last lesson: "Don't darn."

You see, captains of industry don't. Even so much as an office boy who aspires to become a captain of industry doesn't. And the woman in the office who spends her evenings mending her stockings and washing her handkerchiefs, misses, say, the moving pictures where the man in the office is adding to his stock of general information. This tendency to revert to type has been the fatal handicap of the past. By the faint beginnings of an intention to discard it, you differentiate the new woman in commerce from her predecessor the business woman. By way of discipline that girl there at the green cloth covered table, whose bag of war knitting hangs on the back of her chair the while she's shipping furs from Russia, will leave it at home to-morrow. Cecile Bornozi wouldn't have done a million dollars' worth of business with the French Government the past year if she had stopped to knit. And if her thoughts had been on her stockings, she might have missed important details in railway rolling stock. In her room at the Hotel Savoy in London, I never saw a needle or thimble or spool of thread. But on her table I noticed System, the magazine of business.

APPROACHING HIGH FINANCE IN FRANCE

Over on the banks of the Seine even as here on the banks of the Hudson, they are teaching women now the things that Cecile Bornozi knows. Not so long ago I stood in the École Pratique de Haut Enseignement Commercial pour les Jeunes Filles in Paris. This practical school of high commercial instruction for young girls is in the Rue Saint Martin in an old monastery, the Ancien Prieure de Saint Martin des Champs, where the Government has given them quarters. Here a high vaulted room of prayer has been turned into an amphitheatre. On rows of benches lifted tier after tier above the grey and while tiled floor, a hundred and twenty-five girls sat facing a new future. For the first time in history, la jeune fille who has always been more domestic minded than the young girl of any other nation except Germany, is being taught to be commercially minded. Curiously enough, "Thou shalt not darn" is a fundamental precept for success laid down by the director of the new school in France even as at the new school in America. Mlle. Sanua in Paris has to be perhaps even more insistent about it than Miss Wylie in New York. These are 125 girls of the bourgeoise families, any one of whom, if the great war had not come about, would be this morning going to market with her mother to learn the relative values of the different varieties of soup greens. And this afternoon she would be occupied, needle in hand, on a chemise or a robe de nuit for her trousseau. Now she has been called to a totally new environment. Here she sits on a wooden bench, the sofa pillow she has brought with her at her back, a fountain pen in hand, her note book on her knee, adjusting herself to a career which up to 1914 no one so much as dreamed of for her. She is hearing this morning a lecture on commercial law, delivered by Mme. Suzanne Grinberg, one of Paris' famous lawyers. Le Professeur sits on a high stool before a great walnut table, her shapely hands in graceful gesture accentuating her legal phrases. Every little while you catch the "n'est ce pas?" with which she closes a period. And now and then she turns to the blackboard behind her to illustrate her meaning with a diagram.

Mlle. Sanua passes the school catalogue for my inspection and I notice a course of study that includes: industrial trade marks, designs, etc.; foreign commercial legislation; commercial documents, buying and selling, banking, etc.; bookkeeping, commercial and financial arithmetic; course in merchandising, including textiles, dyes, etc.; political economy, including the distribution of wealth, the monetary systems of the world, the consumption of wealth; pauperism, insurance, and charities; the state and its rôle in the economic order, taxes, socialism; economic geography and world markets; law, including public law, civil law and laws relating to women; foreign languages. This is the curriculum now being approached by the young girl who up to yesterday had nothing more serious in the world to occupy her leisure than to sit at the window with an embroidery frame in her lap watching and waiting for a husband.

But you see three years ago, four years ago, Pierre marched by the window in a poilu's blue uniform and he may never come back. Marriage has hitherto been the fixed fact of every French girl's life. Now numbers of women must inevitably, inexorably find another career. These girls here are many of them the daughters of professional men, doctors and lawyers. The girl in the third row back with the blue feather in her hat is the niece of President Poincare. That one with the pretty soft brown eyes in the front row is married. The wife of a manufacturer who is serving his country as a lieutenant in the army, she is trying as best she may to take his place at the head of the great industrial enterprise he had to leave at a day's notice when his call to the colours came. She found herself confronted with all sorts of difficult situations. Somehow she's managed so far by sheer force of will and somewhat perhaps by intuition to come through some pretty narrow situations. For the future she's not willing to take any more such chances. She has come to learn all that a school has to teach of the scientific principles and the established facts of commerce. Two girls here are the granddaughters of one of the leading merchants of the Havre. Their brother, who was to have succeeded to the management of the celebrated financial house, gave his life for his country instead at the Marne. And these girls, with the consent of the family, have dedicated their lives to taking their brother's place in the economic upbuilding of France to which the financial world looks forward after the war.

You see like this the new woman in commerce all over the world is planning for a career that will never again rest with stenography and typewriting. Bringing furs from Russia and wheat from Canada is more interesting. There is nothing like preparedness. You are almost sure to do that for which you have specially made ready. And one glance at the programme of study for the École Pratique de Haut Enseignement Commercial shows clearly enough to any one who reads, that it is what Cecile Bornozi with her flashing glance calls the "big venture" which is the ultimate aim of this girl with the new note book on her knee. Meantime France can scarcely wait for her to complete her training. Mlle. Sanua has almost to stand at the door of the Ancien Prieure to turn away the employers who come to the Rue St. Martin to offer positions to her pupils. "Always they are asking," she says, "have I any more graduates ready?"

Avocat Suzanne Grinberg's soft musical voice goes on in the amphitheatre expounding commercial law. Outside in her adjoining office, the little stone walled room with the religious Gothic window, Mlle. Sanua tells me how it has come about, this new attitude on the part of her country to women who are going to find economic independence in the business world. In the cold little room in a war burdened land where coal is $80 a ton, we draw our chairs closer to the tiny grate. Mlle. Sanua leans forward and selects two fagots to be added to the fire that must be carefully conserved with rigid war time economy.

As she begins to talk, I catch the look in her eyes, the glow of idealism that I have felt somewhere before. Where? Ah, yes. It was Frau Anna von Wunsch in whose eyes I have seen the gleam that flashed the same feminist message. Frau von Wunsch was before the war the presedient of Die Frauenbanck. This was for Germany a most revolutionary institution that hung out its gold lettered sign at 39 Motzstrasse, Berlin, a woman's bank in a land where it was contrary to custom for a married woman to be permitted to do any banking at all. But "Women will never become a world power until they become a money power," said Frau von Wunsch. And they put that motto in black letters on all of their letter heads and checks. The armies of the world are now entrenched between the Seine and the Rhine and since 1914 of course hardly any personal word at all has come through the censored lines from the feminists of Germany to the feminists of France. One does not even know what has become of Frau von Wunsch and her Frauenbanck over there in Mittel Europa. But the ideal that she lighted, flames now in every land.

Mlle. Sanua's plan too is for a new woman in commerce who shall be a money power and a world power. And perhaps it may be France that is temperamentally fitted to lead all lands in achieving that ideal. The jeune fille, so carefully trained for domesticity only, has been known to develop wonderful business qualities after marriage. Invariably in the small shops of France it is Madame who presides at her husband's cash drawer. A woman's hand has led industries for which France is world famous: Mme. Pommerey whose champagne is chosen by the epicure in every land, Mme. Paquin whose house has dictated clothes for the women of all countries, and Mme. Duval whose restaurants are on nearly every street corner of Paris. The commercial instinct is really latent in every French woman. There is scarcely a French household in which a husband making an investment of any kind does not first consult with his wife. This birthright then, why not develop it by training and add scientific knowledge to intuition?

That was the proposition with which the French Minister of Commerce was approached at the beginning of the war. It was his own daughter who came to the Bureau of State over which he presided, with a new programme. Mlle. Valentine Thomson is the editor of La Vie Feminine, in whose columns she had already advocated wider business opportunities for women on the ground that France would have need of women in many new capacities. Now she came to ask that the High Schools of Commerce throughout the land should be opened to girls. Hitherto they had been exclusively for boys. The Minister of Commerce took the matter under consideration. The argument that girls should be prepared for responsibilities that every year of war would more surely bring to them sounded to him logical enough. Besides Mlle. Valentine Thomson is a daughter with a most pretty and persuading way, a way that is as helpful to a feminist as to any other woman. So it happened that the Minister of Commerce, in September, 1915, issued a circular recommending the opening of the national Schools of Commerce to women. The Ministry could only recommend. Each Chamber of Commerce could ultimately decide for its own city. And there were but three cities in which the final court of authority refused, Paris, Lyons and Marseilles.

Then in Paris Mlle. Sanua decided that women too must somehow have their chance. She had already organised her countrywomen in the Federation of French Toy Makers, for which she has far flung ambitions. This new industry which she is putting on its feet in France, she has planned shall supplant the made-in-Germany toys in the markets of the world. But the women who are handling the industry must know how on more than a domestic scale. And Paris, the metropolis of France, offered them no commercial training. In the spring of 1916 Mlle. Sanua decided to go to the Department of State about the matter. There the Minister of Commerce, M. Thomson, furrowed his brow: "After all, Mademoiselle," he said, "have women the mentality for business? The Ministry of War has opened employment in its offices to women. And these girls now whom the Government has admitted to clerkships here, some of them seem quite useless. Mademoiselle," he added wearily, "is a woman's brain really capable for commerce?"

"Train it. Then try it. What we need is schools," said Mlle. Sanua.

A few moments later the conversation turned on the toy industry. "What do you know about the toy industry?" asked the Minister of State curiously. She told him. And as the woman talked, his wonder grew. She did know about toys, that which would enable the French to defeat the Germans in this branch of commerce after the other defeat is finished. Would Mlle. Sanua give a lecture on the toy industry before the Association Nationale d'Expansions Economique? And would she make a report before the Conference Economique des Allies? Which she did. So here was a woman who had a brain worth while for commerce. Well, there might be others. If the Chamber of Commerce in Paris was still doubtful, the Ministry of Commerce would take a chance on endorsing Mlle. Sanua's proposal. They secured for her the Ancien Prieure. And she established the school for which she gives her services. She has gathered a faculty which includes celebrated names in France, most of whom are serving without compensation. Three former Ministers of Commerce form part of the committee of patronage for the school. And the first diplomas last June were conferred by a state official, the Inspector General of Education. For France is arriving at the conclusion that she will have need of trained women as well as such men as she can muster for the great economic conflict that is going to follow when the other battle flags are furled.

So here at the Ancien Prieure 125 new women are coming into commerce. "N'est ce pas?" I hear Avocat Suzanne Grinberg's voice repeat. Mlle. Sanua adds another fagot to the fire. Again as she looks up her eyes are illumined with the ideal that animates her in the service in which she is now engaged for her country. I think the women of France will be a money power and a world power.

See them starting on the way. Already the Bank of France to-day has 700 women employés, the Credit Foncier has 400, and the Credit Lyonnaise has 1200 women employés. Clerical positions in all the government departments, including the War Office, have been opened to women. M. Metin, the under secretary of the French Ministry of Finance, has recently appointed Mlle. Jeanne Tardy an attaché of his department, the first time in the history of France that a woman has held such a position.

Now in every country this same movement has taken place. Russia has had women clerks at the War Office, the Ministries of the Interior, Agriculture, Education, Transportation, and at the Chancelleries of the Imperial Court and Crown Property. The Imperial Russian Bank employed women by preference.

In the German government bureaus and offices, the women employés outnumber the men and they are to be found now in every bank in Germany. There are even new women in commerce in Germany conducting business houses that soldier husbands have left in their hands, who are beginning openly to rebel against the restriction which excludes women along with "idiots, bankrupts, and dishonest traders" from the Bourse in Berlin. And recently a petition has been addressed to the Reichstag for the removal of this bar sinister in business.

MOVING ON LONDON'S FINANCIAL DISTRICT

Probably the largest invasion of the business office, whether that of the government or of the private employer, has taken place in England. No less than 278,000 women have directly replaced in commerce men released for military duty. Petticoats in the district that is known as the "city," I suppose are as unprecedented as they could be anywhere in the world. The most visionary, advanced feminist, who before 1914 might have timidly suggested such an invasion, would have been curtly dismissed with, "It isn't done." And in truth I believe it never would have been done without a war. Down in Fenchurch Avenue, in the great shipping district, I was told: "Really, don't you know, this is the last place we ever expected to see women. But they are here."

The gentleman who spoke might have come out of a page of "Pickwick Papers." His silk hat hung on a nail in the wall above his desk. And he wore a black Prince Albert coat. He looked over his gold bowed eye glasses out into the adjoining room at the clerical staff of the Orient Steamship Company of which he has charge. He indicated for my inspection among the grey haired men on the high stools, rows of women on stools specially made higher for their convenience. And he spoke in the tone of voice in which a geologist might refer to some newly discovered specimen.

It was withal a very kindly voice and there was in it a distinct note of pride when he said: "Now I want you to see a journal one of my girls has done." He came back with it and as he turned the pages for my inspection, he commented: "I find the greatest success with those who at 17 or 18 come direct from school, 'fresh off the arms,' as we say in Scotland. They, well, they know their arithmetic better. My one criticism of women employés is that some of them are not always quite strong on figures. And they lack somewhat in what I might call staying power. Business is business and it must go on every day. Now and then my girls want to stay home for a day. And the long hours, 9:30 to 5:00 in the city, well, I suppose they are arduous for a woman."

"Mr. Clarke," I said, "may I ask you a question: What preparation have these new employés had for business?"

And it turns out, as a matter of fact, most of them haven't had any. A large number of this quarter of a million women who came at the call of the London Board of Trade to take the places of men in the offices, are of the class who since they were "finished" at school, have been living quiet English lives in pleasant suburbs where the rose trees grow and everybody strives to be truly a lady who doesn't descend to working for money. It is difficult for an American woman of any class to visualise such an ideal. But it was a British fact. There were thousands of correct English girls like this, whose pulses had never thrilled to a career who are finding it now suddenly thrust upon them.

"Mr. Clarke," I said, "suppose a quarter of a million men were to be hastily turned loose in a kitchen or nursery to do the work to which women have been born and trained for generations. Perhaps they might not be able to handle the job with just the precision of their predecessors. Now do you think they would?"

Mr. Clarke raised his commercial hand in a quick gesture of protest: "Dear lady," he said, "I remember when my wife once tried me out one day in the nursery—one day was enough for her and for me—I, well, I wasn't equal to the strain. Frankly, I'm quite sure most men wouldn't have the staying power for the tasks you mention."

So you see, in comparison, perhaps the new women on the high stools that have been specially made to their size, are doing pretty well anyhow. There are 73,000 more of them in government offices, the lower clerkships in the civil service having been opened to them since the war. And no less than 42,000 more women have replaced men in finance and banking.

Really, it was like taking the last trench in the Great Push when the women's battalions arrived at Lombard and Threadneedle streets. That bulwark of the conservatism of the ages, the Bank of England, even, capitulates. And the woman movement has swept directly past the resplendent functionary in the red coat and bright brass buttons who walks up and down before its outer portals like something the receding centuries forgot and left behind on the scene. He still has the habit of challenging so much as a woman visitor. It is a hold-over perhaps from the strenuous days of that other woman movement when every government institution had to be barricaded against the suffragettes, and your hand bag was always searched to see if you carried a bomb. But the bright red gentleman is more likely to let you by now than before 1914.

Inside, as you penetrate the innermost recesses, you will go past glass partitioned doors through which are to be seen girls' heads bending over the high desks. And you will meet girl clerks with ledgers under their arms hurrying across court yards and in and out and up and down all curious, winding, musty passage ways. I know of nowhere in the world that you feel the solemn significance of the new woman movement more than here as you catch the echo of these new footsteps on stone floors where for hundreds of years no woman's foot has ever trod before.

The Bank of England isn't giving out the figures about the number of its women employés. An official just looks the other way and directs you down the corridor to put the inquiry to another black frock coat. O, well, if that's the way they feel about it! Others with less ivy on the walls may speak. The London and Southwestern Bank which before the war employed but two women, and these stenographers, now has 900 women. One of London's greatest banks, the London, City and Midland, has among 3000 employés 2600 women. The new woman in commerce is emerging in England and these are some of the verdicts on her efficiency:

Bank of England: "We find the women quick at writing, slow at figures. We have been surprised to find that they do as well as they do. But they are not so efficient as men."

London, City and Midland Bank: "For accuracy, willingness, and attention to duty, we may say that women employés excel."

Morgan and Grenfells: "We employ women on ledger work. But we find they lack the esprit de corps of men. And they don't like to work after hours."

Barclay's Bank: "We cannot speak too highly of our women clerks. They have shown great zeal to acquire a knowledge of the necessary details."

London and Southwestern Bank: "Women employés are even more faithful and steady than men. But when there is a sudden rush of work, as say at the end of the year, they go into hysterics. We find that we cannot let them see the work piled up. It must be given out to them gradually. This, I think, is due to inexperience. When women have had the same length of experience and the same training as men, we see no reason why they should not be equally as capable."

Now that's about the way the evidence runs. You would probably get it about like that anywhere in Europe. There is some criticism. Isn't it surprising that there is not more when you remember that it is mostly raw recruits chosen by chance whose services are being compared with the picked men whom they have replaced? In England in 1915 the Home Office moved to provide educational facilities for women for their new commercial responsibilities. There was appointed its Clerical and Business Occupations Committee which opened in London, and requested the mayors of all other cities similarly to open, emergency training classes for giving a ground work in commercial knowledge and office routine. These government training courses cover a period of from three to ten weeks. It is rather sudden, isn't it, three weeks' preparation for a job in preparation for which the previous incumbent had years'?

And there are thousands of the women who have gone into the offices without even that three weeks' training. The cousin of the wife of the head of the firm knew of some woman of "very good family" whose supporting man was now enlisted and who must therefore earn her own living. Or some other woman was specially recommended as needing work. And there was another method of selection: "She had such nice manners and she was such a pretty little thing I liked her at once, don't you know."

WHAT EVERY WOMAN KNOWS

'Um, yes, I do know. Somewhere in America once there was an editorial chief who said to me, his assistant, "Now I need a secretary. There'll be some here to-day to answer my advertisement. Won't you see them and let me know about their qualifications." There were, as I remember, some fourteen of them, grey haired and experienced ones, technically expert and highly recommended ones, college trained ones, and one was a dimpled little thing with pink cheeks and eyes of baby blue. My detailed report was quite superfluous. Through the open door, as I entered his office, the chief had one glance: "That one," he said eagerly, "that little peach at the end of the row. She's the one I want."

Like that, little peaches are getting picked in all languages. And after them are the others fresh from the gardens where the rose trees grow. And among these ornamental companions of her employer's selection, the really useful employé who gets in, finds herself at a disadvantage. The little peach "bears" the whole woman's wage market. She has hysterics: all the wise commercial world shakes its head about the staying power of woman in business. And the whole female of the species gets listed on the pay roll at two thirds man's pay.

The Orient Steamship Company, I believe, is giving equal pay for equal work. To an official of another steamship company complaining of the inefficiency of women employés, Sir Kenneth Anderson, President of the Orient Line, put the query, "How much do you pay them?" "Twenty-five shillings a week," was the answer. "Then you don't deserve to have efficient women," was the prompt retort. "We pay those who prove competent up to three pounds a week. And they're such a success we've decided we can't let them go after the war." But Sir Kenneth Anderson is the son of one of England's pioneer feminists, Dr. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, and the nephew of another, Mrs. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, president of the National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies. And I suppose there isn't another business house in London that has the Orient Steamship Company's vision. Women clerks in London business circles generally are getting twenty shillings to thirty shillings a week. The city of Manchester, advertising for women clerks for the public health offices, offered salaries respectively of ten shillings, eighteen shillings and twenty shillings a week, "candidates to sit for examination."

Little peaches might not be worth more, it is true. Who, at the Ancien Prieure in Paris, holds open the door of commerce for women in France.

If you can, this is the hour of your opportunity. The women's battalions are with every month of the war drawing nearer, moving onward toward the president's office. The London and Southwestern Bank has advanced 200 of its women clerks to the cashier's window. The London City and Midland Bank a year ago promoted a woman to the position of manager of one of its branches. It was the first time that a woman in England had held such a position. Newspaper reporters were hurriedly despatched to Sir Edward Holden, the president, to see about it. But he only smilingly affirmed the truth of the rumour that had spread like wildfire through the city. It was indeed so. And he had no less than thirty more women making ready for similar positions.

Over in France at Bordeaux and at Nancy in both cities the first class graduated from the High School of Commerce after the admission of women, had a woman leading in the examinations. In the same year, 1916, a girl had carried off the first honours in the historic Gilbart Banking Lectures in London. I suppose no other event could have more profoundly impressed financial circles. The Banker's Magazine came out with Rose Esther Kingston's portrait in a half page illustration and the announcement that a new era in banking had commenced. It was the first time that women had been admitted to the lectures. There were some sixty-two men candidates who presented themselves for examination at the termination of the two months' course. Rose Kingston, who outstripped them all, had been for a year a stenographer in the correspondence department of the Southwestern Bank. Now she was invited to the cashier's desk.

To correctly estimate the achievement, it should be remembered that the men with whom she competed, had years of commercial background and this girl had practically one year. There were so many technical terms with which they were as familiar as she is with all the varieties of voile. What was the meaning of "allonge"? she asked three of her fellow employés bending over their ledgers before she found one who was willing to make it clear that this was the term for the piece of paper attached to a bill of exchange. Fragment by fragment like this, she picked up her banking knowledge. Once the Gilbart lecturer mentioned the "Gordon Case," with which every man among his hearers was quite familiar. She searched through three volumes to get an intelligent understanding of the reference. Meantime, I think she did "darn" nights. You see, her salary was thirty shillings a week.

THE NEW WOMAN AT THE PARTING OF THE WAYS

This is for the feminine mind the besetting temptation most difficult to avoid. Can we give up our "darning" and all of the habits of domesticity which the word connotes? It is the question which women face the world over to-day. Success beckons now along the broad highway of commerce. But the difficult details of living detain us on the way to fame or fortune. And we've got to cut the apron-strings that tie us to yesterday if we would go ahead. Which shall it be, new woman or old? Most of us either in business or the professions cannot be both. Dr. Ella Flagg Young, widely known as the first woman to so arrive at the top of her profession as Superintendent of Schools in the city of Chicago, received a salary of $10,000 a year. She had made it the inviolable rule of her life to live as comfortably as a man. She told me that she did not permit her mind to be distracted from her work for any of the affairs of less moment that she could hire some one else to attend to. She did not so much as buy her own gloves. Her housekeeper-companion attended to all of her shopping. And never, she said, even when she was a $10 a week school teacher, had she darned her own stockings!

There are a few women who have, it is true, managed to achieve success in spite of the handicap of domestic duties. But they must be women of exceptional physique to stand the strain. I know a business woman in New York who, at the head of a department of a great life insurance company, enjoys an income of $20,000 a year. Yet that woman still does up with her own hands all of the preserves that are used in her household. Her husband, who is a physician with a most lucrative practice, you will note doesn't do preserves. He wouldn't if the family never had them.

A woman who is a member of the New York law firm of which her husband is the other partner was with him spending last summer at their country place. She, during their "vacation," put up a hundred cans of fruit. I think it was between strawberry time and blackberry time that she had to return to town to conduct a case in court. She had cautioned her husband that while she was gone, he be sure to "see about" the little green cucumbers. But, of course, he didn't. What heed does a man—and he happens also to be a judge of one of the higher courts—give to little green cucumbers? Long after they should have been picked, they had grown to be large and yellow, which, as any woman knows, takes them way past their pickling prime. That was how the woman who cared about little green cucumbers found them, when she returned from the city. In despair she threw them all out on the ground. The next day, turning the pages of her cook book, she happened to discover another use for yellow cucumbers. Putting on a blue gingham sunbonnet, she went out to the field back of the orchard and laboriously gathered them all up again. And she could not rest until on the shelf in her farm house cellar stood three stone crocks filled with sweet cucumber pickle. She just couldn't bear to see those cucumbers go to waste. It is the sense of thrift inculcated by generations of forbears whose occupation was the practice of housewifery.

The Judge doesn't have any such feeling about pickles or any other household affairs. When he goes home at night, he reads or smokes or plays billiards. When the lady who is his law partner goes home, even though their New York residence is at an apartment hotel, she finds many duties to engage her attention. The magazines on the table would get to be as ancient as those in a dentist's office if she didn't remove the back numbers. Who else would conduct the correspondence that makes and breaks dinner engagements and do it so gracefully as to maintain the family's perfect social balance? Who else would indite with an appropriate sentiment and tie up and address all the Christmas packages that have to be sent annually to a large circle of relatives? Well, all these and innumerable other things you may be sure the Judge wouldn't do. He simply can't be annoyed with petty and trivial matters. He says that for the successful practice of his profession, he requires outside of his office hours rest and relaxation. Now the other partner practises without them. And you can see which is likely to make the greater legal reputation.

In upper Manhattan, at a Central Park West address, a woman physician's sign occupies the front window of a brown stone front residence. She happens to be a friend of mine. Katherine is one of the most successful women practitioners in New York. Nine patients waited for her in the ante room the last time I was there. From the basement door, inadvertently left ajar, there floated up the sound of the doctor's voice: "That chicken," she was saying, "you may cream for luncheon. I have a case at the hospital at two o'clock. We'll hang the new curtains in the dining room at three. And—well, I'll be down again before I start out this morning."

I know the Doctor so well that I can tell you pretty accurately what were the other domestic duties that had already received her attention. She has a most wonderful kitchen. She had glanced through it to see that the sink was clean and that each shining pot and pan was hanging on its own hook. She had given the order for the day to the butcher. She had planned the dinner for the evening, probably with a soup to utilise the remnants of Sunday's roast. Then—I have known it to happen—some one perhaps called, "O, say, dear, here's a button coming loose. Could you, 'er, just spare the time?'

Well, ultimately she stands in the doorway of her office with her calm, pleasant "This way, please" to the first patient, and turns her attention to the diagnosis, we will say, of an appendicitis case. Meanwhile, down the front staircase a carefree gentleman has passed on his way to the doorway of the other office. He is the doctor whose sign is in the other front window of this same brown stone residence. What has he been doing in the early morning hours before taking up his professional duties for the day? His sole employment has been the reading of the morning newspaper! Katherine never interrupts him in that. It is one of the ways she has been such a successful wife. She learned the first year of their marriage how important he considered concentration. MAN'S EASY WAY TO FAME

Now you can see that there's a difference in being these two doctors. And it's a good deal easier being the doctor who doesn't have to sew on his own buttons and who needs take less thought than the birds of the air about his breakfasts and his luncheons and his dinners, how they shall be ordered for the day. That's the way every man I know in business or the professions has the bothersome details of living all arranged for him by some one else. I noted recently a business man who was thus speeded on his way to his office from the moment of his call to breakfast. The breakfast table was perfectly appointed. "Is your coffee all right, dear?" his wife inquired solicitously. It was. As it always is. The eggs placed before him had been boiled just one and a half minutes by the clock. He has to have them that way, and by painstaking insistence she has accomplished it with the cook. The muffins were a perfect golden brown. He adores perfection and in every detail she studies to attain it for him. The breakfast that he had finished was a culinary achievement. "Don't forget your sanatogen, dear," she cautioned as he folded his napkin. "Honey, you fix it so much better than I can," he suggested in the persuasive tone of voice that is his particular charm. She hastily set down her coffee cup and rose from the table to do it. Then she selected a white carnation from the centrepiece vase and pinned it in his buttonhole. He likes flowers. She picked up his gloves from the hall table, and discovering a tiny rip, ran lightly upstairs to exchange them for another pair, while he passed round the breakfast table, hat in hand, kissing the five children in turn. Then he kissed her too and went swinging down the front walk to catch the last commuters' train.

I happened to see him go that morning. But it's always like that. And when she welcomes him home at night, smiling on the threshold there, the five children are all washed and dressed and in good order, with their latest quarrel hushed to cherubic stillness. The newest magazine is on the library table beneath the softly shaded reading lamp, and a carefully appointed dinner waits. All of the wearisome domestic details of existence he has to be shielded from. For he is a captain of industry.

There are even more difficult men. I know of one who writes. He has to be so protected from the rude environment of this material world that while the muse moves him, his meals carefully prepared by his wife's own hands, because she knows so well what suits his sensitive digestion, are brought to his door. She may not speak to him as she passes in the tray. No servant is ever permitted to do the cleaning in his sanctum. It disturbs the "atmosphere," he says. So his wife herself even washes the floor. Hush! His last novel went into the sixth edition. He's a genius. And his wife says, "You have to take every care of a man who possesses temperament. He's so easily upset." For the lack of a salad just right, a book might have failed.

'Er, do you know of any genius of the feminine gender for whom the gods arrange such happy auspices as that? Is there any one trying to be a prominent business or professional woman for whom the wrinkles are all smoothed out of the way of life as for the prominent professional man whom I have mentioned?

We who sat around a dinner table not long ago knew of no such fortunate women among our acquaintance. That dinner, for instance, hadn't appointed itself. Our hostess, a magazine editor, had hurried in breathless haste from her office at fifteen minutes of six to take up all of the details that demand the "touch of a woman's hand." The penetrating odour of a roast about to burn had greeted her as she turned her key in the hall door. She rushed to the oven and rescued that. Two of the napkins on the table didn't match the set. Marie, the maid, apologetically thought they would "do." They didn't. It was the magazine editor who reached into the basket of clean laundry for the right ones and ironed them herself because Marie had to be busy by this time with the soup. The flowers hadn't come. She telephoned the florist. He was so sorry. But she had ordered marguerites, and there weren't any that day. Yes, if roses would answer instead, certainly he would send them at once. The bon bons in yellow she found set out on the sideboard in a blue dish. Why weren't they in the dish of delicate Venetian glass of which she was particularly fond? Well, because the dish of cate Venetian glass had gone the way of so many delicate dishes, down the dumb waiter shaft an hour ago. Marie didn't mean to break it, as she assured her mistress by dissolving in tears for some five minutes while more important matters waited. A particular sauce for the dessert depending on the delicacy of its flavouring, the editor must make herself. Well—after everything was all right, it was a composed and unperturbed and smiling hostess who extended the welcome to her invited company.

The guest of honour was a woman playwright whose problem play was one of the successes of last season. She has just finished another. That was why she could be here to-night. While she writes, no dinner invitation can lure her from her desk. "You see, I just have to do my work in the evening," she told us. "After midnight I write best. It's the only time I am sure that no one will interrupt with the announcement that my cousin from the West is here, or the steam pipes have burst, or some other event has come to pass in a busy day."

We had struck the domestic chord. Over the coffee we discussed a book that has stirred the world with its profound contribution to the interpretation of the woman movement. The author easily holds a place among the most famous. We all know her public life. One who knew her home life, told us more. She wrote that book in the intervals of doing her own housework. The same hand that held her inspired pen, washed the dishes and baked the bread and wielded the broom at her house—and made all of her own clothes. It was necessary because her entire fortune had been swept away. Does any one know of a man who has made a profound contribution to literature the while he prepared three meals a day or in the intervals of his rest and recreation cut out and made, say, his own shirts? I met last year in London this famous woman who has compassed all of these tasks on her way to literary fame. She's in a sanitarium trying to recuperate from nervous prostration.

THE RECIPE FOR SUCCESS

The hand that knows how to stir with a spoon and to sew with a needle has got to forget its cunning if women are to live successfully and engage in business and the professions. The woman of the present generation has struggled to do her own work in the office and, after hours that of the woman of yesterday in the home. It's two days' work in one. It has been decided by the scientific experts, you remember, who found the women munition workers of England attempting this, that it cannot be done consistently with the highest efficiency in output. And the Trade Unions in industry endorse the decision.

This is the critical hour for the new women in commerce to accept the same principle. I know it is difficult to adopt a man's standard of comfortable living on two-thirds a man's pay. And I know of no one to pin carnations in your buttonhole. But somehow the woman in business has got to conserve her energy and concentrate her force in bridging the distance that has in the past separated her from man's pay. There is now the greatest chance that has ever come to her to achieve it—if she prepares herself by every means of self-improvement to perform equal work. Don't darn. Go to the moving pictures even, instead.

For great opportunities wait. Lady Mackworth of England, when her father, Lord Rhondda, was absent on a government war mission in America recently, assumed complete charge of his vast coal and shipping interests. So successful was her business administration, that on his resignation from the chairmanship of the Sanatogen Company, she was elected to fill his place. Like this the new woman in commerce is going to take her seat at the mahogany desk. Are you ready?

The New York newspapers have lately announced the New York University's advertisement in large type: "Present conditions emphasise the opportunities open to women in the field of business. Business is not sentimental. Women who shoulder equal responsibilities with men will receive equal consideration. It is unnecessary to point out that training is essential. The high rewards do not go to the unprepared. Classes at the New York University are composed of both men and women."

Why shouldn't they be? It is with madame at his side that the thrifty shop keeper of France has always made his way to success.

The terrible eternal purpose that flashes like zigzag lightning through the black war clouds of Europe, again appears. From the old civilisation reduced to its elements on the battle fields, a new world is slowly taking shape. And in it, the new man and the new woman shall make the new money power—together.