Wonderful Balloon Ascents/Part 2/Chapter 1

PART II.

THE HISTORY OF THE AEROSTATION FROM THE YEAR 1783.

CHAPTER I.

The Open Route—Travels and Travellers—Great Increase in the Number of Air Voyages—Lyons, Ascent of "Le Flesselles"—Milan, Ascent of Adriani—Flight of a Balloon from London—Lost Balloons in the Chief Towns of Europe.

|

From the year 1783, in which aerostation had its birth, and in which it was carried to a degree of perfection, beside which the progress of aeronauts in our days seems small, a new route was opened up for travellers. The science of Montgolfier, the practical art of Professor Charles, and the courage of Roziers, subdued the scepticism of those who had not yet given in their adhesion to the possible value of the great discovery, and throughout the whole of France a feverish degree of enthusiasm in the art manifested itself. Aerial excursions now became quite fashionable. Let it be understood that we do not here refer to ascents in fixed balloons, that is, in balloons which were attached to the earth by means of ropes more or less long.

M. Biot narrates that, in his young days, when aeronautic ascents were less known than they are in these times, there was in the plain of Grenelle, at the mill of Javelle, an establishment where balloons were constantly maintained for the accommodation of amateurs of both sexes who wished to make ascents in what were called "ballons captifs," or balloons anchored, so to speak, to the earth by means of long ropes. They were for a considerable time the rage of fashionable society, and it is not recorded that any accidents resulted from the practice. Of course it may be easily understood with these safe balloons the adventurous aeronauts never ascended to any great height. The reader will find this subject treated under the chapter of military aerostation.

We are at present specially engaged with the narrative of the first attempts in aerostation—the first experiments in the new discovery. We have followed with interest the exciting details of the first adventurous ascents, in which the genius of man first essayed the unexplored paths of the heavens. Yet a continued record of aerial voyages would not be of the same interest. The results of subsequent expeditions, and the impressions of subsequent aeronauts are the same as those already described, or differ from them only in minor points. No important advance is recorded in the art. We shall therefore endeavour not to confine ourselves to the narrative of a dry and monotonous chronology, but to select from the number of ascents that have taken place within the last eighty years, only those whose special character renders them worthy of more detailed and severe investigation.

In order to give an idea of the rapid multiplication of aeronautic experiments, it will suffice to state that the only aeronauts of 1783 are Roziers, the Marquis d'Arlandes, Professor Charles, his collaborateur the younger Robert, and a carpenter, named Wilcox, who made ascents at Philadelphia and London.

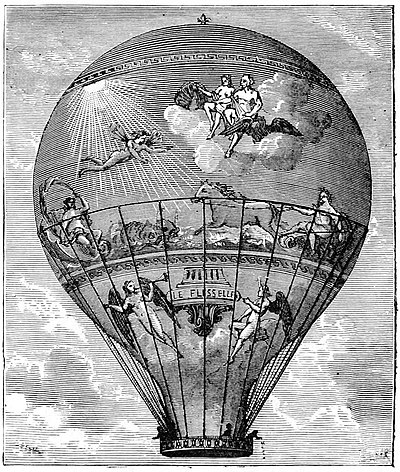

A number of balloons were remarkable for the beauty and elegance which we have already spoken of. Among the most beautiful we may mention the "Flesselles" balloon and Bagnolet's balloon.

Bagnolet's Balloon.

Of the ascents which immediately succeeded those that have been treated in the first part of our volume, and which are the most memorable in the early annals of aerostation, that of the 17th of January, 1784, is remarkable. It took place at Lyons. Seven persons went into the car on this occasion—Joseph Montgolfier, Roziers, the Comte de Laurencin, the Comte de Dampierre, the Prince Charles de Ligne, the Comte de Laporte d'Anglifort, and Fontaine, who threw himself into the car when it had already begun to move.

A most minute account of this experiment is given in a letter of Mathon de la Cour, director of the Academy of Sciences at Lyons:—

"After the experiments of the Champ de Mars and Versailles had become known," he says, "the citizens of this town proposed to repeat them and a subscription was opened for this purpose. On the arrival of the elder Montgolfier, about the end of September, M. de Flesselles, our director, always zealous in promoting whatever might be for the welfare of the province and the advancement of science and art, persuaded him to organise the subscription. The aim of the experiment proposed by Montgolfier was not the ascent of any human being in the balloon. The prospectus only announced that a balloon of a much larger size than any that had been made would ascend—that it would rise to several thousand feet, and that, including the animals that it was proposed it should carry, it would weigh 8,000 lbs. The subscription was fixed at £12, and the number of subscribers was 360."

It was on these conditions that Montgolfier commenced his balloon of 126 feet high and 100 feet in diameter, made of a double envelope of cotton cloth, with a lining of paper between. A strength and consistency was given to the structure by means of ribbons and cords.

The work was nearly finished when Roziers went up in his fire-balloon from La Muette. Immediately the Comte de Laurencin pressed Montgolfier to allow him to go up in the new machine. Montgolfier was only too glad of the opportunity—refused up to this time by the king—of going up himself. From thirty to forty people made application to go with the aeronauts; and on the 26th of December, 1678, Roziers, the Comte de Dampierre, and the Comte de Laporte, arrived in Lyons with the same intention. Prince Charles also arrived; and as his father had taken one hundred subscriptions, his claim to go up could not be refused.

But while the public papers were full of ascents at Avignon, Marseilles, and Paris, it is impossible to describe the vexation of Roziers, when he discovered that Montgolfier's new balloon was not intended to carry passengers, and had not been, from the first, constructed with that view. He suggested a number of alterations, which Montgolfier adopted at once.

On the 7th of January, 1784, all the pieces of which the balloon was composed were carried out to the field called Les Brotteaux, outside the town, from which the ascent was to be made. This event was announced to take place on the 10th and at five o'clock on the morning of that day; but unexpected delays occurred, and in the necessary operations the covering was torn in many places.

On the 15th the balloon was inflated in seventeen minutes, and the gallery was attached in an hour—the fire from which the heated air was obtained requiring to be fed at the rate of 5 lbs. of alder-wood per minute; but the preparations had occupied so much time, that it was found, when everything was complete, that the afternoon was too far advanced for the ascent to be made. This machine was destined to suffer from endless misfortunes. It took fire while being inflated, and, several days afterwards, it was damaged by snow and rain. But nothing discouraged Roziers and his companions. Places had been arranged in the gallery for six persons. After the balloon was at last inflated, Prince Charles and the Comes de Laurencin, Dampierre, and Laporte threw themselves into the gallery. They were all armed, and were determined not to quit their places to whoever might come. Roziers, who wished at the last to enjoy a high ascent, proposed to reduce the number to three, and to draw lots for the purpose. But the gentlemen would not descend. The debate became animated. The four voyagers cried to cut the ropes. The director of the Academy, to whom application was made in this emergency, admiring the resolution and the courage of the four gentlemen, wished to satisfy them in their desire. Accordingly the ropes were cut; but at that moment M. Montgolfier and Roziers threw themselves into the gallery. At the same time a certain M. Fontaine, who had had much to do in the construction of the machine, threw himself in, although it had not previously been arranged that he should be of the party. His boldness in jumping in was pardoned, on the ground of his services and his zeal.

In going away the machine turned to the south-west, and bent a little. A rope which dragged along the ground seemed to retard its ascent; but some intelligent person having cut this with a hatchet, it began to right itself and ascend. At a certain height it turned to the north east. The wind was feeble, and the progress was slow, but the imposing effect was indescribable. The immense machine rose into the air as by some effect of magic. Nearly 100,000 spectators were present, and they were greatly excited at the view. They clapped their hands and stretched their arms towards the sky; women fainted away, or (for some reasons best known to themselves) found relief for their excitement in tears; while the men, uttering cries of joy, waved their handkerchiefs, and threw their hats into the air.

The form of the machine was that of a globe, rising from a reversed and truncated cone, to which the gallery was attached. The upper part was white, the lower part grey; and the cone was composed of strips of stuff of different colours. On the sides of the balloon were two paintings, one of which represented History, the other Fame. The flag bore the arms of the director of the Academy, and above it were inscribed the words "Le Flesselles."

The voyagers observed that they did not consume a fourth of the quantity of combustibles after they had risen into the air, which they consumed when attached to the earth. They were in the gayest humour, and they calculated that the fuel they had would keep them floating till late in the evening. Unfortunately, however, after throwing more wood on the fire, in order to get up to a greater altitude, it was discovered that a rent had been made in the covering, caused by the fire by which the balloon had been damaged two or three days previously. The rent was four feet in length; and as the heated air escaped very rapidly by it, the balloon fell, after having sailed above the earth for barely fifteen minutes.

The descent only occupied two or three minutes, and yet the shock was supportable. It was observed that as soon as the machine had touched the earth all the cloth became unfolded in a few seconds, which seemed to confirm the opinion of Montgolfier, who believed that electricity had much to do in the ascent of balloons. The voyagers were got out of the balloon without accident, and were greeted with the most enthusiastic applause.

Le Flesselles.

On the day of the ascent, the opera of "Iphigenia in Aulis" was given, and the theatre was thronged by a vast assemblage, attracted thither in the hope of seeing the illustrious experimentalists. The curtain had risen when M. and Madame de Flesselles entered their box, accompanied by Montgolfier and Roziers. At sight of them the enthusiasm of the house rose to fever pitch. The other voyagers also entered, and were greeted with the same demonstrations. Cries arose from the pit to begin the opera again, in honour of the visitors. The curtain then fell, and when it again rose, after a few moments, the actor who filled the rôle of Agamemnon advanced with crowns, which he handed to Madame de Flesselles, who distributed them to the aeronauts. Roziers placed the crown that had been given to him upon Montgolfier's head.

When the actress who played the part of Clytemnestra, sung the passage beginning—

"I love to see these flattering honours paid,"

the audience at once applied her song to the circumstances, and re-demanded it, which request the actress complied with, addressing herself to the box in which the distinguished visitors sat. The demonstrations of admiration were continued after the opera was over; and during the whole of the night the gentlemen of the balloon ascent were serenaded.

Two days afterwards, Roziers having appeared at a ball, received further proofs of admiration and honours; and when, on the 22nd of January, he departed for Dijon on his return to Paris, he was accompanied as in a triumph by a numerous cavalcade of the most distinguished young men of the city.

There was, however, at Paris, much discontent with the ascent of "Le Flesselles;" and the Journal de Paris, which notices so enthusiastically the other ascents of that epoch, speaks slightingly of that at Lyons.

The next great ascent took place at Milan, on the 25th of February, 1784, under the direction of the Chevalier Paul Andriani, who had a balloon constructed by the Brothers Gerli, at his own expense. We read that this balloon was 66 feet in diameter, and that the envelope was composed of cloth, lined in the interior with fine paper.

The balloon was not in all respects constructed like that which rose at Lyons. The grating which supported the fire that kept up the supply of hot air was placed at the mouth of the opening. It was made of copper, was six feet in diameter, and was secured by a number of transverse beams of wood. M. Andriani thought it best to place his fire—contrary to general usage—a little way above the mouth of the opening, and he found out that the activity of the fire was in proportion with that of the air which entered and fed it.

In place of making use of a gallery like that employed by Montgolfier, as much to manage the fire as to carry the traveller and the fuel, he substituted a wide basket, suspended by cords to the edge of the opening of the balloon, at such a distance that fuel could be thrown on with the hand without being inconvenienced by the heat.

Everything being in readiness, the machine was carried to Moncuco, the splendid domain of Andriani, where the first experiments were made; for this gentlemen knew that as the populace are impatient, they are also often unreasonable, and jump to the hastiest and most inconsiderate conclusion when, in witnessing scientific experiments, any of the arrangements happen to be imperfect, and the results in any respect prove unsuccessful.

Andriani did not deceive himself, for, sure enough, his first attempt did not come up to expectation. The reasons for this failure were the too great quantity of air which the fire drew in, and the unsuitable character of the fuel used.

On the 25th of February, 1784, a second attempt was made. The fire was lighted under the machine, at first with dry birch-wood and afterwards with a bituminous composition, ingeniously concocted by one of the Brothers Gerli. In less than four minutes the balloon was completely inflated, and the men employed to hold it down with ropes perceived that it was on the point of rising. The aeronauts then gave the order to let go. Scarcely was the balloon let off, when it gently rose a short distance, and then flew in a horizontal direction towards a palace in the neighbourhood. In order that the structure should not be destroyed on the walls and the roof of the palace, the voyagers heaped on the fuel, and the spectators, who had gathered together from the surrounding villages, then saw this strange vessel of the air rising with rapidity to a surprising height. Such a phenomenon was so astonishing, that those who beheld it could hardly believe their own eyes; and when the balloon disappeared from view, the delight they had manifested was dashed with fear for the fate of the bold aeronauts. The latter, seeing that the balloon was driving through the air towards a range of rocky hills in the neighbourhood, and perceiving, on the other hand, that their stock of combustibles was nearly exhausted, judged it prudent to descend. They diminished their fire, and came gradually down, warning the multitude below of their intention by means of a speaking-trumpet.

In the course of the descent the balloon alighted upon a large tree, to the great peril of the travellers; but as soon as the fire was increased it again mounted and got clear from the branches while the people below, grasping the cords that were hung out to them, guided the machine to the spot which the voyagers indicated. To descend to terra firma was then a comparatively easy matter, and it was safely accomplished. The fire, which in the case of the French balloons had dried, calcined, and almost consumed the upper part of the balloon, had no evil effect upon that of Andriani, which came down looking as fresh as if it had never been used.

The new idea had now passed the frontiers of France, in which it was originally conceived, and among the other nations, as at first in France, the power of the inflated balloon came to be tested everywhere by the construction of small toy globes.

It was just about five months after the first experiment at Annonay—viz., on the 25th of November, 1783—that the first balloon ascended in London. We are informed, in the History of Aerostation by Tiberius Cavallo, that an Italian, Count Zambeccari, who was staying in the English capital, made a balloon of silk, covered with a varnish of oil. Its diameter was ten feet, and its weight eleven pounds. It was gilded for the double purpose of enhancing its appearance and preventing the escape of air. After having been exposed to public inspection for several days, it was filled three parts full of hydrogen gas, a tin bottle was suspended from it, containing an address to whoever might find it when it should fall, and it was let off from the Artillery Ground, in presence of a vast assembly.

On the 11th of December, 1783, a little balloon, made of gold-beaters' skin, was let off publicly at Turin. This was an experiment similar to that which had been tried at Paris in September. The balloon was seen to penetrate the clouds, then to mount still higher, and finally to disappear entirely in five minutes fifty-four seconds from the time when it was set free.

It was natural, after the experiments made long before with electric paper kites, to employ the balloon in the investigation of the electric conditions of the atmosphere. The first to use it for this purpose was the Abbé Berthelon de Montpellier. He sent up a number of balloons, to which he had attached pieces of metal, long and narrow, and terminating in a cylinder of glass, or other substance suitable for the purpose of isolation, and he obtained sufficient electricity by these means to demonstrate the phenomena of attraction and repulsion, as well as electric sparks.

Cavallo mentions an accident which took place in England about this time, and which served as a warning to all who had to do with balloons filled with hydrogen gas. A balloon thus inflated had been sent up at Hopton, near Matlock, and was found by two men near Cheadle, in Staffordshire. These ingenious persons carried it within doors, and having wished to fully inflate it—half the gas having by this time escaped—they applied a pair of bellows to its mouth. By this means they only forced out the volume of the hydrogen gas that was left; and this gas, coming in contact with a candle that had been placed too near, exploded. The report was louder than that of a cannon, and so powerful was the shock that the men were thrown down, the glass blown out of the windows, and the house otherwise damaged. The men suffered severely, their hair, beards, and eyebrows being completely burnt away, and their faces severely scorched.

At Grenoble, in Dauphiné, De Baron let off a balloon on the 13th of January, 1784. It rose, and at first took a northern direction; but, having encountered a current of air, it was carried away in a south-easterly direction, and after flying a distance of three-quarters of a mile, it fell, having traversed this distance in fifteen minutes.

A society, under the presidency of the Abbé de Mably, having constructed a balloon thirty-seven feet high and twenty feet in diameter, sent it off from the court of the Castle of Pisançon, near Romano, on the same day, the 13th of February. At first it was carried to the south by a strong north wind, but after it had risen to 1,000 feet above the surface, its course was changed towards the north. It was calculated that, in less than five minutes, this balloon rose to the height of 6,000 feet.

On the 16th of the same month the Count d'Albon threw off from his gardens at Franconville a balloon inflated with gas, and made of silk, rendered air-tight by a solution of gum-arabic. It was oblong, and measured twenty-five feet in height, and seventeen feet in diameter. To this balloon a cage, containing two guinea-pigs and a rabbit, was suspended. The cords were cut, and the inflated globe rose to an enormous height with the greatest rapidity. Five days afterwards it was found at the distance of eighteen miles, and it is remarkable that, in spite of the cold of the season, and particularly of the elevated region through which the balloon had been passing, the animals were not only living, but in good condition.

On the 3rd of February, 1784, the Marquis de Bullion sent up a paper balloon, of about fifteen feet in diameter. A flat sponge, about a foot square, placed in a tin dish and drenched with a pint of spirits of wine, was the only apparatus made use of to create a supply of heated air. It rose at Paris, and three hours afterwards it was found near Basville, about thirty miles from the capital.

On the 15th of the same month Cellard de Chastelais sent up a paper balloon. Heated air was supplied on this occasion by a paper roll, enclosing a sponge, and soaked in oil, spirits of wine, and grease. A cage, which contained a cat, was attached to this air globe. In thirty-five minutes it had mounted so high that it looked but like the smallest star, and in two hours it had flown a distance of forty-six miles from the place where it was thrown off. The cat was dead, but it was not discovered from what cause.

The first balloon that traversed the English channel was sent off at Sandwich, in Kent, on the 22nd of February, 1784. It was five feet in diameter, and was inflated with hydrogen gas. It rose rapidly, and was carried toward France by a north-west wind. Two hours and a half after it had been let off it was found in a field about nine miles from Lille. The balloon carried a letter, instructing the finder of the balloon to communicate with William Boys, Esq., Sandwich, and to state where and at what time it was found. This request was complied with.

On the 19th of February a similar balloon, five feet in diameter, was sent up from Queen's College, Oxford. It was spherical, and was made of Persian silk, coated with varnish. It was the first balloon sent up from that city.

De Saussure makes mention, in a letter dated from Geneva, the 26th of March, 1784, of certain experiments made in that town with the electricity of the atmosphere by means of fixed balloons—i.e., balloons attached to the earth by ropes, which gave forth sparks and positive electricity.

Mention is also made of a certain M. Argand, of Geneva, who had the honour of making balloon experiments at Windsor in the presence of King George III., Queen Charlotte, and the royal family. About this time (1784) balloons became "the fashion," and frequent instances occur of their being raised by day and night, by means of spirit-lamps, to the great delight of multitudes of spectators.

A letter from Watt to Dr. Lind, of Windsor, dated from Birmingham, 25th December, 1784, narrates an experiment made the summer preceding with a balloon inflated with hydrogen. The balloon was made of fine paper covered with a varnish of oil and filled two-thirds with hydrogen gas, and one-third common air. To the neck of the balloon was attached a sort of squib two feet long, the fuse of which was ignited when the balloon was inflated. The night was calm and dark, and a great multitude was assembled to witness the ascent, which was accomplished with a success that gave delight to all; for, at the end of six minutes the fuse communicated with the squib, and the explosion was like the sound of thunder. The men who saw it from a distance, but were not present at its ascent, took it for a meteor. "Our intention," says Watt, "was, if possible, to discover whether the reverberating sound of thunder was due to echoes or to successive explosions. The sound occasioned by the detonation of the hydrogen gas of the balloon in this experiment, does not enable us to form a definite judgment; all that we can do is to refer to those who were near the balloon, and who affirm that the sound was like that of thunder."