A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Motet

MOTET (Barb. Lat. Motetum, Motectum, Mutetus, Motellus, Motulus; Ital. Mottetto). A term, which for the last three hundred years has been almost exclusively applied to certain pieces of Church Music, of moderate length, adapted to Latin words (selected, for the most part, either from Holy Scripture, or the Roman Office-Books), and intended to be sung, at High Mass, either in place of, or immediately after, the Plain Chaunt Offertorium for the Day. [See Mass; Offertorium.] This definition, however, extends no farther than the conventional meaning of the word. Its origin involves some very grave etymological difficulties, immeasurably increased by the varied mode of spelling adopted by early writers. For instance, the form Motulus, can scarcely fail to suggest a corruption of Modulus—a Cantilena, or Melody; and, in support of this derivation, we may remind our readers, that in the 13th and 14th Centuries, and even earlier, the terms Motetus and Motellus, were constantly applied to the Voice-part afterwards called Medius or Altus. On the other hand, the idea that the true etymon is supplied by the Italian word, Mottetto, diminutive of Motto, and equivalent to the French mot, or bon mot, a jest, derives some colour from the fact that it was unquestionably applied, in the first instance, to a certain kind of profane music, which, in the 13th Century, was severely censured by the Church, in common with the Rondellus, another kind of popular melody, and the Conductus, a species of Sæcular Song, in which the subject in the Tenor was original, and suggested the other parts, after the manner of the Guida of a Canon. Again, it is just possible that the varying orthography to which we have alluded may, originally, have involved some real distinction, no longer recognisable. But, in opposition to this view it may be urged that the charge of licentiousness was brought against the Motet under all its synonyms, though Ecclesiastical Composers continued to use its themes as Canti fermi, as long as the Polyphonic Schools remained in existence—to which circumstance the word most probably owes its present conventional signification.

The earliest purely Ecclesiastical Motets of which any certain record remains to us are those of Philippus de Vitriaco, whose Ars compositionis de Motetis, preserved in the Paris Library, is believed to have been written between the years 1290 and 1310. Morley tells us that the Motets of this author 'were for some time of all others best esteemed and most used in the Church.' Some others, scarcely less antient, are printed in Gerbert's great work De Cantu et musica sacra—rude attempts at two-part harmony, intensely interesting, as historical records, but intolerable to cultivated ears.

Very different from these early efforts are the productions of the period, which, in our article, Mass, we have designated as the First Epoch of practical importance in the history of Polyphonic Music—a period embracing the closing years of the 13th Century, and the first half of the 14th, and represented by the works of Guglielmo Du Fay, Egydius Bianchoys, Eloy, Dunstable, Vincenzo Faugues, and some other Masters, whose compositions are chiefly known through the richly illuminated volumes which adorn the Library of the Sistine Chapel, in which they are written, in accordance with the custom of the Pontifical Choir, in characters large enough to be read by the entire body of Singers, at one view. These works are full of interest; and, like the earliest Masses, invaluable, as studies of the polyphonic treatment of the Modes.

Equally interesting are the productions of the Second Epoch, extending from the year 1430 to about 1480. The typical Composers of this period were Giovanni Okenheim (or Ockegem), Caron, Gaspar, Antonius de Fevin, Hobrecht, and Giovanni Basiron, in whose works we first begin to notice a remarkable divergence between the music adapted to the Motet and that set apart for the Mass. From the time of Okenheim, the leader of the School, till the middle of the 16th Century, Composers seem to have regarded the invention of contrapuntal miracles as a duty which no one could avoid without dishonour. For some unexplained reason, they learned to look upon the Music of the Mass as the natural and orthodox vehicle for the exhibition of this peculiar kind of ingenuity: while, in the Motet, they were less careful to display their learning, and more ready to encourage a certain gravity of manner, far more valuable, from an æsthetic point of view, than the extravagant complications which too often disfigure the 'more ambitious compositions they were intended to adorn. Hence it frequently happens, that, in the Motets of this period, we find a consistency of design, combined with a massive breadth of style, for which we search in vain in contemporary Masses.

The compositions of the Third Epoch exhibit all the merits noticeable in those of the First and Second, enriched by more extended harmonic resources, and a far greater amount of technical skill. It was during this period, comprising the two last decads of the 15th Century, and the two first of the 16th, that the Great Masters of the Flemish School, excited to enthusiasm by the matchless genius of Josquin des Prés, made those rapid advances towards perfection, which, for a time, placed them far above the Musicians of any other country in Europe, and gained for them an influence which was everywhere acknowledged with respect, and everywhere used for pure and noble ends. The Motets bequeathed to us by these earnest-minded men are, with scarcely any exception, constructed upon a Canto fermo, supplied by some fragment of grave Plain Chaunt, or suggested by the strains of some well-known Sæcular Melody. Sometimes, this simple theme is sung, by the Tenor, or some other principal Voice, entirely in Longs, and Breves, while other Voices accompany it, in florid Counterpoint, with every imaginable variety of imitation and device. Sometimes, it is taken up by the several Voices, in turn, after the manner of a Fugue, or Canon, without the support of the continuous part, which is only introduced in broken phrases, with long rests between them. When, as is frequently the case, the Motet consists of two movements—a Pars prima, and Pars secunda—the Canto fermo is sometimes sung, by the Tenor, first, in the ordinary way, and then backwards, in Retrograde Imitation, cancrizans. In this, and other cases, it is frequently prefixed to the composition, on a small detached Stave, and thus forms a true Motto to the work, to the imitations of which it supplies a veritable key, and in the course of which it is always treated in the same general way. [See Inscription.] But, side by side with this homogeneity of mechanical construction, we find an infinite variety of individual expression. Freed from the pedantic trammels, which at one period exercised so unhealthy an influence upon the Mass, the Composer of the Motet felt bound to give his whole attention to a careful rendering of the words, instead of wasting it, as he would certainly have done under other circumtances, upon the concoction of some astounding Inversion, or inscrutable Canon. Hence, the character of the text frequently offers a tolerably safe criterion as to the style of work; and we are thus enabled to divide the Motets, not of this Epoch only, but of the preceding and following periods also, into several distinct classes, each marked by some peculiarity of more or less importance.

Nowhere, perhaps, do we find more real feeling than in the numerous Motets founded on passages selected from the Gospels, such as Jacobus Vaet's 'Egressus Jesus,' Jahn Gero's renderings of the Parable of the Pharisee and the Publican, and others of similar intention. The treatment of these subjects, though exhibiting no trace of the dramatic element, is highly characteristic, and shews a deep appreciation of the sense of the Sacred Text, embracing every variety of expression, from the triumphant praises of the Magnificat, to the deep sadness of the Passion of our Lord. The oldest known example of the former subject, treated in the Motet style, is a Magnificat, for three Voices, by Du Fay. One of the earliest renderings of the latter is Hobrecht's 'Passio D.N.J.C. secundum Matthæum,' a work full of the deepest pathos, combined with some very ingenious part-writing. Scarcely less beautiful is the later 'Passio secundum Marcum,' by Johannes Galliculus; and Loyset Compère has left us a collection of Passion Motets of extraordinary beauty.

The Book of Canticles was also a fruitful source of inspiration. Among the finest specimens extant are three by Johannes de Lynburgia (John of Limburg)—'Surge propera,' 'Pulcra es anima mea,' and 'Descende in hortum meum'; Du Fay's 'Anima mea liquefacta est'; a fine setting of the same words, by Enrico Isaac; Antonius de Fevin's 'Descende in hortum meum'; and, among others, by Craen, Gaspar, Josquin des Prés, and the best of their compatriots, a remarkably beautiful rendering of 'Quam pulcra es anima mea,' for Grave Equal Voices, by Mouton, from which we extract the opening bars, as a fair example of the style:—

![{ << \new Staff { \time 4/2 \clef bass \key f \major << \new Voice = "T1" \relative f { \stemUp r1 r r r f\breve_\markup { \smaller \italic "Tenore I." } f1 bes |

a r2 a | c c d1 | c\breve ~ | c1 r2 a | c1. c2 | d1 c s4_"etc." }

\new Voice = "T2" \relative f { \stemDown f\breve_\markup { \smaller \italic "Tenore II." } f1 bes | a1 r2 a | c c d1 | c2. bes8[ c] d2 c | c4 bes a1 g2 | a g4 f e2 a | g a1 g4 f | a2 g1 c2 ~ | c b a1 } >> }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "T1" { Quam pul -- cra es }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "T2" { Quam pul -- cra es }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key f \major << \new Voice = "B1" { \stemUp R\breve*6 c\breve c1 f e r2 e | g g a1 | s4 }

\new Voice = "B2" \relative f, { \stemDown R\breve*4 f\breve f1 bes | a r2 a | c c d1 | c\breve | r1 r2 a }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "B1" { Quam pul -- cra es }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "B2" { Quam pul -- cra es a -- ni -- ma me -- a. } >> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/4/m4js6bv8neq0n9xvhph5suwi6n29syr/m4js6bv8.png)

A host of beautiful Motets were written in honour of Our Lady, and all in a style of peculiarly delicate beauty; such as Du Fay's 'Salve Virgo,' 'Alma Redemptoris,' 'Ave Regina,' and 'Flos florum, fons amorum'; Brasart's 'Ave Maria'; Bianchoys' 'Beata Dei genitrix'; Archadelt's 'Ave Maria'; several by Brumel, and Loyset Compère; and a large number by Josquin des Prés, including the following beautiful little 'Ave vera virginitas' in Perfect Time, with its remarkable progression of Consecutive Fifths arising from the necessity of maintaining the strictness of a Canon, in the Fifth below, led by the Superius, and resolved by the Tenor.

The Lamentations of Jeremiah have furnished the text of innumerable beautiful movements, in the Motet style, by Joannes Tinctor, Hykaert, Gaspar, Pierre de la Rue, Agricola, and, above all, Carpentrasso, whose Lamentations were annually sung in the Sistine Chapel, until, in the year 1587, they were displaced to make room for the superb compositions of Palestrina. [See Lamentations.]

The greater Festivals of the Church, as well as those of individual Saints, gave occasion for the composition of countless Motets, among which must be reckoned certain Sequences, set, in the Motet style, by some of the Great Composers of the 15th and 16th Centuries; notably a 'Victimæ paschali,' by Josquin des Prés, founded on fragments of the old Plain Chaunt Melody, interwoven with the popular Rondelli, 'D'ung aultre amer,' and 'De tous biens pleine,' and a 'Stabat Mater,' by the same writer, the Canto fermo of which is furnished by the then well-known Sæcular Air, 'Comme femme.' This last composition, too long and complicated to admit of quotation, was reprinted, by Choron, in 1820, and will well repay serious study.

Less generally interesting than the classes we have described, yet, not without a special historical value of their own, are the laudatory Motets, dedicated to Princes, and Nobles of high degree, by the Maestri attached to their respective Courts. Among these may be cited Clemens non Papa's 'Cæsar habet naves,' and 'Quis te victorem dicat,' inscribed to Charles V; Adrian Willaert's ' Argentum et aurum'; and many others of like character.

Finally, we are indebted to the Great Masters of the 15th and 16th Centuries for a large collection of Næniæ, or Funeral Motets, which are scarcely exceeded in beauty by those of any other class. The Service for the Dead has been treated, by Composers of all ages, with more than ordinary reverence. In the infancy of Discant, the so-called Organizers who were its recognized exponents did all they could to make the 'Officium Defunctorum' as impressive as possible: and, acting up to their light, endeavoured to add to its solemnity by the introduction of discords which were utterly forbidden in Organum of the ordinary kind. Hence arose the doleful strain, antiently called 'Litaniæ mortuorum discordantes.'

It is interesting to compare these excruciating harmonies with the Dirge of Josquin des Prés in memory of his departed friend and tutor, Okenheiin. This fine Motet is founded on the Plain Chaunt Melody of 'Requiem æternam,' which is sung in Breves and Semibreves by the Tenor, to the original Latin words, while the four other Voices sing a florid Counterpoint, to some French verses, beginning, 'Nymphes des boir, Déesses des fontaines.' It was printed, at Antwerp, in 1544; and presents so many difficulties to the would-be interpreter, that Burney declares himself 'ashamed to confess how much time and meditation' it cost him. The simple harmonies of the peroration, 'Requiescat in pace,' are so touchingly beautiful, that we transcribe them in preference to the more complicated passages by which they are preceded.

The earliest printed copies of the Motets we have described were given to the world by Ottaviano dei Petrucci, who published a volume, at Venice, in 1502, called 'Motette, A. numero trentatre'; another, in 1503, called 'Motetti de passioni, B.'; a third, in 1504, called 'Motetti, c. C.' [App. p.720 "'Motetti C.' (the British Museum possesses a single part-book of this work"]; a fourth, in 1505—'Motetti libro quarto'; and, in the same year, a book, for five Voices—'Motetti a cinque libro primo'—which, notwithstanding the promise implied in its title, was not followed by the appearance of a companion volume. In 1511, the inventor of printed music removed to Fossombrone; where, between the years 1514, and 1519, he published four more volumes of Motets, known, from a figure engraved on the title-page, as the 'Motetti della Corona.' In 1538, Antonio Gardano published, at Venice, a collection, called—also from a figure on its title-page—'Motetti del Frutto'. These were pirated, at Ferrara, under the name of 'Motetti della Scimia,' with the figure of an Ape devouring a Fruit: whereupon, Gardano issued a new volume, with the figure of a Lion, and Bear, devouring an Ape. Between the years 1527, and 1536, nineteen similar volumes were issued, in Paris, by Pierre Attaignant; and many more were printed, in the same city, by Adrian le Roy, and Robert Ballard. These collections, containing innumerable works by all the great Composers of the earlier periods, are of priceless worth. Of some of Petrucci's only one copy is known to exist, and that, unhappily, incomplete. The Library of the British Museum possesses his Second, Third, and Fourth Books of 'Motetti della Corona,' besides his First and Third Books of Josquin's Masses, and the First of Gardano's 'Motetti del Frutto'; and this, taking into consideration the splendid condition of the copies, must be regarded as a very rich collection indeed.

During the Fourth Epoch—embracing the interval between the death of Josquin des Prés, in 1521, and the production of the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli', in 1565—the development of the Motet coincided so closely with that of the Mass, that it seems necessary to add but very little to the article already written upon that subject. The contemporaneous progress of the Madrigal did, indeed, exercise a healthier influence upon the former than it could possibly have done in presence of the more recondite intricacies, common to the latter: but, certain abuses crept into both. The evil habit of mixing together irrelevant words increased to such an extent, that, among the curiosities preserved in the Library of the Sistine Chapel, we find Motets in which every one of the five Voices is made to illustrate a different text, throughout. In this respect, if not in others, an equal amount of deterioration was observable in both styles.

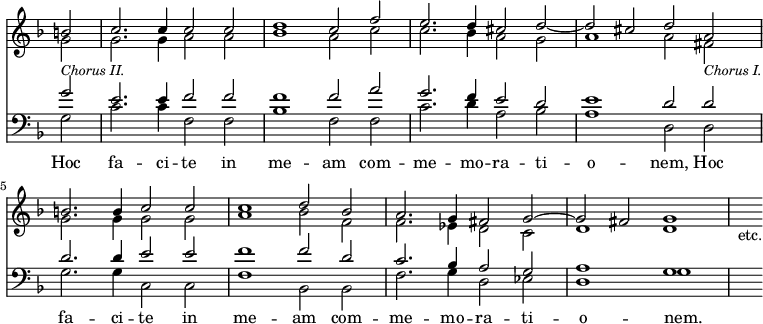

The Fifth Epoch—extending from the year 1565, to the beginning of the following Century—witnessed the sudden advance of both branches of Art to absolute perfection: for Palestrina, the brightest genius of the age, was equally great in both, and has left us Motets as unapproachable in their beauty as the 'Missa Papæ Marcelli.' The prolific power of this delightful Composer was no less remarkable than the purity of his style. The seven Books of Motets printed during his life-time contain two hundred and two compositions, for four, five, six, seven, and eight Voices, among which may be found numerous examples of all the different classes we have described. About a hundred others, including thirteen for twelve Voices, are preserved, in MS., in the Vatican Library, and among the Archives of the Pontifical Chapel, the Lateran Basilica, S. Maria in Vallicella, and the Collegium Romanum; and there is good reason to believe that many were lost through the carelessness of the Maestro's son, Igino. The entire contents of the seven printed volumes, together with seventy-two of the Motets hitherto existing only in MS., have already been issued as a first instalment of the complete edition of Palestrina's works now in course of publication by Messrs. Breitkopf & Härtel of Leipzig; and this, probably, is as many as we can now hope for, as it is well known that some of the MS. copies we have mentioned are incomplete. Among so many gems, it is difficult to select any number for special notice. Perhaps the finest of all are those printed in the Fourth Book of Motets for five Voices, the words of which are taken from the Book of Canticles: but, the two Books of simpler compositions for four Voices are full of treasures. Some are marvels of contrapuntal cleverness; others—where the character of the words is more than usually solemn—as unpretending as the plainest Faux bourdon. As an example of the more elaborate style, we transcribe a few bars of 'Sicut cervus desiderat,' contrasting them with a lovely passage from 'Fratres ego enim accepi,' a Motet for eight Voices, in which the Institution of the Last Supper is illustrated by simple harmonies of indescribable beauty.

Sicut cervus.

Fratres ego.

Palestrina's greatest contemporaries, in the Roman School, were, Vittoria, whose Motets are second only in importance to his own, Morales, Felice and Francesco Anerio, Bernadino and Giovanni Maria Nanini, Luca Marenzio, and Francesco Suriano. The honour of the Flemish School was supported, to the last, by Orlando di Lasso, a host in himself. The Venetian School boasted, after Willaert, Cipriano di Rore, Andrea and Giovanni Gabrieli, and, especially, Giovanni Croce, the originality of whose style was only exceeded by its wonderful delicacy and sweetness, which are well shewn in the following example.

In England, the Motet was cultivated, with great success, by some of the best Composers of the best period. The 'Cantiones sacræ' of Tallis and Byrd, will bear comparison with the finest productions of the Roman or any other School, those of Palestrina alone excepted. And, besides these, we possess a number of beautiful Motets by Dr. Tye, John Taverner, John Shepherd, Dr. Fayrfax, Robert Johnson, John Digon, John Thorne, and several other writers not unknown to fame. Though the Latin Motet was, as a matter of course, banished from the Services of the Church after the change of Religion, its style still lived on, in the Full Anthem, of which so many glorious examples have been handed down to us, in our Cathedral Choir-books; for, the Full Anthem is a true Motet, notwithstanding the language in which it is sung; and it is certain that some of the purest specimens of the style were originally written in Latin, and adapted to English words, afterwards—as in the case of Byrd's 'Civitas sancti tui,' now always sung as 'Bow thine ear, Lord.' Orlando Gibbons's First (and only) Set of 'Madrigals and Mottets,' printed in 1612, furnishes a singular return to the old use of the word. They are all Sæcular Songs; as are, also, Martin Pierson's 'Mottects,' published eighteen years later.

The Sixth Epoch, beginning with the early years of the 17th Century, was one of sad decadence. The Unprepared Dissonances introduced by Monteverde sapped the very foundations of the Polyphonic Schools, and involved the Motet, the Mass and the Madrigal in a common ruin. Men like Claudio Casciolini and Gregorio Allegri, did their best to save the grand old manner; but, after the middle of the Century, no Composer did it full justice.

The Seventh Epoch inaugurated a new style. During the latter half of the 17th century, Instrumental Music made a rapid advance; and Motets with Instrumental Accompaniments, were substituted for those sung by Voices alone. In these, the old Ecclesiastical Modes were naturally abandoned, in favour of the modern Tonality; and, as time progressed, Alessandro Scarlatti, Leo, Durante, Pergolesi, and other men of nearly equal reputation, produced really great works in the new manner, and thus prepared the way for still greater ones.

The chief glories of the Eighth Epoch were confined to Germany, where Reinhard Keiser, the Bach Family—with Johann Christoph, and Johann Sebastian, at its head—Graun, and Hasse, clothed the Motet in new and beautiful forms which were turned to excellent account by Homilius, and Rolle, Wolf, Hiller, Fasch, and Schicht. The Motets of Sebastian Bach are too well known to need a word of description—known well enough to be universally recognised as artistic creations of the highest order, quite unapproachable in their own peculiar style. With Handel's Motets few Musicians are equally familiar; for it is only within the last few years that the German Handel Society has rescued them from oblivion. Nevertheless, they are extraordinarily beautiful; filled with the youthful freshness of the Composer's early manner. Besides a 'Salve Regina,' the MS. of which is preserved in the Royal Library at Buckingham Palace, we possess a 'Laudate pueri,' in D, used as an Introduction to the Utrecht Jubilate; another in F, a 'Dixit Dominus,' a 'Nisi Dominus,' and, best of all, a lovely 'Silete venti,' for Soprano Solo, with Accompaniments for a Stringed Band, two Oboes, and two Bassoons, the last movement of which, 'Dulcis amor, Jesu care,' was introduced in Israel in Ægypt, on its second revival, in 1756, adapted to the words, 'Hope, a pure and lasting treasure.' It is to be hoped, that, now these treasures are really given to the world, they will not long be suffered to remain a dead letter.

Of the Ninth, or Modern Epoch, we have but little to say. The so-called Motets of the present Century have no real claim to any other title than that of Sacred Cantatas. They were, it is true, originally intended to be sung at High Mass: but, the 'Insanæ et vanæ curæ' of Haydn, the 'Splendente te Deus' of Mozart, and the 'O salutaris' of Cherubini, exquisitely beautiful as they are, when regarded simply as Music, have so little in common with the Motet in its typical form, that one can scarcely understand how the name ever came to be bestowed upon them. The Motets of Mendelssohn, again, have but little affinity with these—indeed, they can scarcely be said to have any; for, in spite of the dates at which they were produced, they may more fairly be classed with the great works of the Eighth Epoch, to which their style very closely assimilates them. We need scarcely refer to his three Motets for Treble Voices, written for the Convent of Trinità de' Monti, at Rome, as gems of modern Art.

All that we have said in a former article, on the traditional manner of singing the Polyphonic Mass, applies, with equal force, to the Motet. It will need an equal amount of expression, and an equal variety of colouring; and, as its position in the Service is anterior to the Elevation of the Host, a vigorous forte will not be out of place, when the sense of the words demands it. It would scarcely be possible to find more profitable studies for the practice of Polyphonic singing than the best Motets of the best period.[ W. S. R. ]