A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Mass

MASS (Lat. Missa; from the words, 'Ite, missa est'—'Depart! the assembly is dismissed'—sung, by the Deacon, immediately before the conclusion of the Service. Ital. Messa; Fr. Messe; Germ. Die Messe). The custom of singing certain parts of the Mass to music of a peculiarly solemn and impressive character has prevailed, in the Roman Church, from time immemorial.

Concerning the source whence this music was originally derived, we know but very little. All that can be said, with any degree of certainty, is, that, after having long been consecrated, by traditional use, to the service of Religion, the oldest forms of it with which we are acquainted were collected together, revised, and systematically arranged, first, by Saint Ambrose, and, afterwards, more completely, by Saint Gregory the Great, to whose labours we are mainly indebted for their transmission to our own day in the pages of the Roman Gradual. Under the name of Plain Chaunt, the venerable melodies thus preserved to us are still sung, constantly, in the Pontifical Chapel, and the Cathedrals of most Continental Dioceses. The specimen we have printed, in the article, Kyrie, will give a fair general idea of their style; and it is worthy of remark, that the special characteristics of that style are more or less plainly discernible in all music written for the Church, during a thousand years, at least, after the compilation of Saint Gregory's great work.

Each separate portion of the Mass was antiently sung to its own proper Tune; different Tunes being appointed for different Seasons, and Festivals. After the invention of Counterpoint, Composers delighted in weaving these and other old Plain Chaunt melodies into polyphonic Masses, for two, four, six, eight, twelve, or even forty Voices: and thus arose those marvellous Schools of Ecclesiastical Music, which, gradually advancing in excellence, exhibited, during the latter half of the 16th century, a development of Art, the æsthetic perfection of which has never since been equalled. The portions of the Service selected for this method of treatment were, the Kyrie, the Gloria, the Credo, the Sanctus, the Benedictus, and the Agnus Dei; which six movements constituted—and still constitute—the musical composition usually called the 'Mass.' A single Plain Chaunt melody—in technical language, a Canto fermo—served, for the most part, as a common theme for the whole: and, from this, the entire work generally derived its name—as Missa 'Veni sponsa Christi'; Missa 'Tu, es Petrus'; Missa 'Iste confessor.' The Canto fermo, however, was not always a sacred one. Sometimes—though not very often during the best periods of Art—it was taken from the refrain of some popular song; as in the case of the famous Missæ 'L'Homme armé,' founded upon an old French love-song—a subject which Josquin des Prés, Palestrina, and many other great Composers have treated with wonderful ingenuity. More rarely, an original theme was selected: and the work was then called Missa sine nomine, or Missa brevis, or Missa ad Fugam, or ad Canones, as the case might be; or named, after the Mode in which it was composed, Missa Primi Toni, Missa Quarti Toni, Missa Octavi Toni; or even from the number of Voices employed, as Missa Quatuor Vocum. In some few instances—generally, very fine ones—an entire Mass was based upon the six sounds of the Hexachord, and entitled Missa ut, re, mi, fa, sol, la, or Missa super Voces Musicales.

Among the earliest Masses of this description, of which perfect and intelligible copies have been preserved to us, are those by Du Fay, Dunstable, Binchoys, and certain contemporaneous writers, whose works characterise the First Epoch of really practical importance in the history of Figured Music—an epoch intensely interesting to the critic, as already exhibiting the firm establishment of an entirely new style, confessedly founded upon novel principles, yet depending, for its materials, upon the oldest subjects in existence, and itself destined to pass through two centuries and a half of gradual, but perfectly legitimate development. Du Fay, who may fairly be regarded as the typical composer of this primitive School, was a Tenor Singer in the Pontifical Chapel, between the years 1380, and 1432. His Masses, and those of the best of his contemporaries, though hard, and unmelodious, are full of earnest purpose; and exhibit much contrapuntal skill, combined, sometimes, with ingenious fugal treatment. Written exclusively in the antient Ecclesiastical Modes, they manifest a marked preference for Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian forms, with a very sparing use of their Æolian and Ionian congeners. These Modes are used, sometimes, at their true pitch; sometimes, transposed a fourth higher—or fifth lower—by means of a B♭ at the signature: but, never, under any other form of transposition, or, with any other signatures than those corresponding with the modern keys of C, or F—a restriction which remained in full force as late as the first half of the 17th century, and was even respected by Handel, when he wrote, as he sometimes did with amazing power, in the older scales. So far as the treatment of the Canto fermo was concerned, no departure from the strict rule of the Mode was held to be, under any circumstances, admissible: but, a little less rigour was exacted, with regard to the counterpoint. Composers had long since learned to recognise the demand for what we should now call a Leading-note, in the formation of the Clausula vera, or True Cadence—a species of Close, invested with functions analogous to those of the Perfect Cadence in modern music. To meet this requirement, they freely admitted the use of an accidental semitone, in all Modes (except the Phrygian) in which the seventh was naturally Minor. But, in order that, to the eye, at least, their counterpoint might appear no less strict than the Canto fermo, they refrained, as far as possible, from indicating the presence of such semitones in their written music, and, except when they occurred in very unexpected places, left the singers to introduce them, wherever they might be required, at the moment of performance. Music so treated was called Cantus fictus: and the education of no Chorister was considered complete, until he was able, while singing it, to supply the necessary semitones, correctly, in accordance with certain fixed laws, a summary of which will be found in the article, Musica Ficta. For the rest, we are able to detect but little attempt at expression; and very slight regard for the distinction between long and short syllables. The verbal text, indeed, was given in a very incomplete form; the word, Kyrie, or Sanctus, written at the beginning of a movement, being generally regarded as a sufficient indication of the Composer's meaning. In this, and other kindred matters, the confidence reposed in the Singer's intelligence was unbounded—a not unnatural circumstance, perhaps, in an age in which the Composer, himself, was almost always a Singer in the Choir for which he wrote.

Even at this remote period, the several movements of the Mass began gradually to mould themselves into certain definite forms, which were long in reaching perfection, but, having once obtained general acceptance, remained, for more than a century and a half, substantially unchanged. The usual plan of the Kyrie has already been fully described. [See Kyrie.] The Gloria, distinguished by a more modest display of fugal ingenuity, and a more cursive rendering of the words, was generally divided into two parts, the Qui tollis being treated as a separate movement. The Credo, written in a similar style, was also subjected to the same method of subdivision, a second movement being usually introduced at the words, 'Et incarnatus est,' or 'Crucifixus,' and, frequently, a third, at 'Et in Spiritum Sanctum.' The design of the Sanctus, though more highly developed, was not unlike that of the Kyrie; the 'Pleni sunt coeli,' being sometimes, and the Osanna, almost always, treated separately. The Benedictus was allotted, in most cases, to two, three, or four Solo Voices; and frequently assumed the form of a Canon, followed by a choral Osanna. In the Agnus Dei—generally divided into two distinct movements—the Composer loved to exhibit the utmost resources of his skill: hence, in the great majority of instances, the second movement was written, either in Canon, or in very complex Fugue, and, not unfrequently, for a greater number of voices than the rest of the Mass.

The best-known composers of the Second Epoch were Okenheim, Hobrecht, Caron, Gaspar, the brothers De Fevin, and some others of their School, most of whom flourished between the years 1430, and 1480. As a general rule, these writers laboured less zealously for the cultivation of a pure and melodious style, than for the advancement of contrapuntal ingenuity. For the sober fugal periods of their predecessors, they substituted the less elastic kind of imitation, which was then called Strict or Perpetual Fugue, but afterwards obtained the name of Canon; carrying their passion for this style of composition to such extravagant lengths, that too many of their works descended to the level of mere learned ænigmas. Okenheim, especially, was devoted to this particular phase of Art, for the sake of which he was ready to sacrifice much excellence of a far more substantial kind. Provided he could succeed in inventing a Canon, sufficiently complex to puzzle his brethren, and admit of an indefinite number of solutions, he cared little whether it was melodious, or the reverse. To such Canons he did not scruple to set the most solemn words of the Mass. Yet, his genius was, certainly, of a very high order; and, when he cared to lay aside these extravagances, he proved himself capable of producing works far superior to those of any contemporary writer.

The Third Epoch was rendered remarkable by the appearance of a Master, whose fame was destined to eclipse that of all his predecessors, and even to cast the reputation of his teacher, Okenheim, into the shade. Josquin des Prés, a Singer in the Pontifical Chapel, from 1471 to 1484, and, afterwards, Maitre de Chapelle to Louis XII, was, undoubtedly, for very many years, the most popular Composer, as well as the greatest and most learned Musician, in Christendom. And, his honours were fairly earned. The wealth of ingenuity and contrivance displayed in some of his Masses is truly wonderful; and is rendered none the less so by its association with a vivacity peculiarly his own, and an intelligence and freedom of manner far in advance of the age in which he lived. Unhappily, these high qualities are marred by a want of reverence which would seem to have been the witty genius's besetting sin. When free from this defect, his style is admirable. On examining his Masses, one is alternately surprised by passages full of unexpected dignity, and conceits of almost inconceivable quaintness—flashes of humour, the presence of which, in a volume of Church Music, cannot be too deeply regretted, though they are really no more than passing indications of the genial temper of a man whose greatness was far too real to be affected, either one way or the other, by a natural light-heartedness which would not always submit to control. As a specimen of his best, and most devotional style, we can scarcely do better than quote a few bars from the Osanna of his Mass, Faysans regrés[1]—

The religious character of this movement is apparent, from the very first bar; and the ingenuity with which the strict Canon is carried on, between the Bass and Alto, simultaneously with the Fugue between the Tenor and Treble, is quite forgotten in the unexpected beauty of the resulting harmonies. Perhaps some portion of the beauty of our next example—the Benedictus from the Missa 'L'Homme armé'—may be forgotten in its ingenuity. It is a strict Canon, in the Unison, by Diminution; and, though intended to be sung by two Voices, is printed in one part only, the singer being left to find out the secret of its construction as best he can—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

A hint at the solution of this ænigma is given, to the initiated, by the double Time-signature at the beginning. [See Inscription.] The intention is, that it should be sung by two Bas Voices, in unison, both beginning at the same time, but one singing the notes twice as quickly as the other: thus—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

This diversity of Rhythm is, however, a very simple matter, compared with many other complications in the same Mass, and still more, in the Missa 'Didadi,' which abounds in strange proportions of Time, Mode, and Prolation, the clue whereto is afforded by the numbers shewn on the faces of a pair of dice! Copious extracts from these curious Masses, as well as from others by Gombert, Clemens non Papa, Mouton, Brumel, and other celebrated Composers, both of this, and the preceding Epoch, will be found in the 'Dodecachordon' of Glareanus (Basle, 154?}, a work which throws more light than almost any other on the mysteries of antient counterpoint.

Of the numerous Composers who flourished during the Fourth Epoch—that is to say, during the first half of the 16th century—a large proportion aimed at nothing higher than a servile imitation of the still idolised Josquin; and, as is usual under such circumstances, succeeded in reproducing his faults much more frequently than his virtues. There were, however, many honourable exceptions. The Masses of Carpentrasso, Morales, Cipriano di Rore, Vincenzo Ruffo, Claude Goudimel, Adriano Willaert, and, notably, Costanzo Festa, are unquestionably written in a far purer and more flowing style than those of their predecessors: and even the great army of Madrigal writers, headed by Archadelt, and Verdelot, helped on the good cause bravely, in the face of a host of charlatans whose caprices tended only to bring their Art into disrepute. Not content with inventing ænigmas 'Ad omnem tonum,' or 'Ung demiton plus bas'—with colouring their notes green, when they sang of grass, or red, when allusion was made to blood—these corrupters of taste prided themselves upon adapting, to the several voice-parts for which they wrote, different sets of words, totally unconnected with each other; and this evil custom spread so widely, that Morales himself did not scruple to mix together the text of the Liturgy, and that of the 'Ave Maria'; while a Mass is still extant in which the Tenor is made to sing 'Alleluia,' incessantly, from beginning to end. When the text was left intact, the rhythm was involved in complications which rendered the sense of the words utterly unintelligible. Profane melodies, and even the verses belonging to them, were shamelessly introduced into the most solemn compositions for the Church. All the vain conceits affected by the earlier writers were revived, with tenfold extravagance. Canons were tortured into forms of ineffable absurdity, and esteemed only in proportion to the difficulty of their solution. By a miserable fatality, the Mass came to be regarded as the most fitting possible vehicle for the display of these strange monstrosities, which are far less frequently met with in the Motet, or the Madrigal. Men of real genius fostered the wildest abuses. Even Pierre de la Rue—who seems to have made it a point of conscience to eclipse, if possible, the fame of Josquin's ingenuity—wrote his Missa, 'O saltitaris Hostia,' in one line, throughout; leaving three out of the four Voices to follow the single part in strict Canon. In the Kyrie of this Mass—which we reprint, in modern notation, from the version preserved by Glareanus[2]—the solution of the ænigma is indicated by the letters placed above and below the notes. C shows the place at which the Contra-tenor is to begin, in the interval of a Fifth below the Superius. T indicates the entrance of the Tenor, an Octave below the Superius: B, that of the Bass, a Fifth below the Tenor. The same letters, with pauses over them, mark the notes on which the several parts are to end. The reader who will take the trouble to score the movement, in accordance with these directions, will find the harmony perfectly correct, in spite of some harshly dissonant passing-notes: but it is doubtful whether the most indulgent critic would venture to praise it for its devotional character.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Petrus Platensis.

It is easy to imagine the depths of inanity accessible to an ambitious composer, in his attempts to construct such a Canon as this, without a spark of Pierre de la Rue's genius to guide him on his way. Such attempts were made, every day: and, had it not been that good men and true were at work, beneath the surface, conscientiously preparing the way for a better state of things, Art would soon have been in a sorry plight. As it was, notwithstanding all these extravagances, it was making real progress. The dawn of a brighter day was very near at hand; and the excesses of the unwise only served to hasten its appearance.

The Fifth Epoch, extending from the year 1565 to the second decad of the following century, and justly called 'The Golden Age of Ecclesiastical Music,' owes its celebrity entirely to the influence of one grave earnest-minded man, whose transcendant genius, always devoted to the noblest purposes, and always guided by sound and reasonable principles, has won for him a place, not only on the highest pinnacle of Fame, but, also, in the inmost hearts of all true lovers of the truest Art.

The abuses to which we have just alluded became, in process of time, so intolerable, that the Council of Trent found it necessary to condemn them, in no measured terms. In the year 1564, Pope Pius IV commissioned eight Cardinals to see that certain decrees of the Council were duly carried out. After much careful deliberation, the members of this Commission had almost determined to forbid the use of any polyphonic music whatever, in the Services of the Church: but, chiefly through the influence of Card. Vitellozzo Vitellozzi, and S. Carlo Borromeo, they were induced to suspend their judgment, until Palestrina, then Maestro di Capella of S. Maria Maggiore, should have proved, if he could, the possibility of producing music of a more devotional character, and better adapted to the words of the Mass, and the true purposes of Religion, than that then in general use. In answer to this challenge, the great Composer submitted to the Commissioners three Masses, upon one of which—first sung in the Sistine Chapel, on the Nineteenth of June, 1565, and since known as the Missa Papæ Marcelli[3]—the Cardinals immediately fixed, as embodying the style in which all future Church music should be composed. It would be difficult to conceive a more perfect model. In depth of thought, intensity of expression, and all the higher qualities which distinguish the work of the Master from that of the pedant, the Missa Papæ Marcelli is universally admitted to be unapproachable; while, even when regarded as a monument of mere mechanical skill, it stands absolutely unrivalled. Yet, except in the employment of the Hypoionian Mode[4]—a tonality generally avoided by the older composers—it depends for its effect, upon the introduction of no new element whatever, either of construction, or of form. Avoiding all show of empty pedantry, and carefully concealing the consummate art with which the involutions of its periods are conducted, it freely uses all the old contrivances of Fugue, and, in the second Agnus Dei, of closely interwoven Canon: but, always, as means towards the attainment of a certain end—never, in place of the end itself. And, this entire subjugation of artistic power to the demands of expression is, perhaps, its most prominent characteristic. It pervades it, throughout, from the first note to the last. Take, for instance, the Christe eleison, in which each Voice, as it enters, seems to plead more earnestly than its predecessor for mercy—

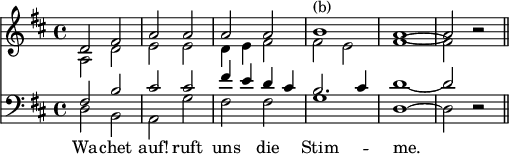

It is impossible, while listening to these touchingly beautiful harmonies, to bestow even a passing thought upon the texture of the parts by which they are produced: yet, the quiet grace of the theme, at (a), and the closeness of the imitation to which it is subjected, evince a command of technical resources which Handel alone could have hidden, with equal success, beneath the appearance of such extreme simplicity. Handel has, indeed, submitted a similar subject to closely analagous treatment—though, in quick time, and with a very different expression—in the opening Tutti of his Organ Concerto in G: and it is interesting to note, that the exquisitely moulded close, at (b), so expressive, when sung with the necessary ritardando, of the confidence of Hope, has been used, by Mendelssohn, interval for interval, in the Chorale, 'Sleepers wake!' from 'Saint Paul,' to express the confidence of Expectation.

We have selected this particular passage for our illustration, principally for the sake of calling attention to these instructive coincidences: but, in truth, every bar of the Mass conceals a miracle of Art. Its subjects, all original, and all of extreme simplicity, are treated with an inexhaustible variety of feeling which shews them, every moment, in some new and beautiful light, Its six voices—Soprano, Alto, two Tenors of exactly equal compass, and two Basses matched with similar nicety—are so artfully grouped as constantly to produce the effect of two or more antiphonal Choirs. Its style is solemn, and devotional, throughout; but, by no means deficient in fire, when the sense of the words demands it. Baini truly calls the Kyrie, devout; the Gloria, animated; the Credo, majestic; the Sanctus, angelic; and, the Agnus Dei, prayerful. Palestrina wrote many more Masses, of the highest degree of excellence; but, none—not even Assumpta est Maria—so nearly approaching perfection, in every respect, as this. He is known to have produced, at the least, ninety-five; of which forty-three were printed during his life-time; and thirty-nine more, within seven years after his death; while thirteen are preserved, in manuscript,[5] among the Archives of the Pontifical Chapel, and in the Vatican Library. The effect produced by these great works upon the prevailing style was all that could be desired. Vittoria, and Anerio, in the great Roman School, Gabrieli, and Croce, in the Venetian, Orlando di Lasso, in the Flemish, and innumerable other Masters, brought forward compositions of unfading interest and beauty. Not the least interesting of these is a Mass, for five voices, in the transposed Æolian Mode, composed by our own great William Byrd, at the time when he was singing, as a Chorister, at Old Saint Paul's. This valuable work was edited, in 1841, for the Musical Antiquarian Society, by Dr. Rimbault, from a copy, believed to be unique, and now safely lodged in the Library of the British Museum. Though composed (if Dr. Rimbault's theory may be accepted, in the absence of a printed date) some years before the Missa Papæ Marcelli, it may fairly lay claim to be classed as a production of the 'Golden Age'; for, it was certainly not printed until after the appearance of Palestrina's Second Book of Masses; moreover, it is entirely free from the vices of the Fourth Epoch, and, notwithstanding a certain irregularity in the formation of some of the Cadences, exhibits unmistakeable traces of the Roman style: a style, the beauties of which were speedily recognised from one end of Europe to the other, exercising more or less influence over the productions of all other Schools, and thereby bringing the music of the Mass, during the latter half of the Sixteenth Century, to a degree of perfection beyond which it has never since advanced.

The Sixth Epoch was one of universal decadence. In obedience to the exigencies of a law with the operation of which the Art-historian is only too familiar, the glories of the 'Golden Age' had no sooner reached their full maturity, than they began to show signs of incipient decay. The bold unprepared discords of Monteverde, and the rapid rise of Instrumental Music, were, alike, fatal to the progress of the Polyphonic Schools. Monteverde, it is true, only employed his newly-invented harmonies in sæcular music: but, what revolutionist ever yet succeeded in controlling the course of the stone he had once set in motion! Other Composers soon dragged the unwonted dissonances into the Service of the Church: and, beyond all doubt, the unprepared seventh sounded the death-knell of the Polyphonic Mass. The barrier between the tried, and the untried, once broken down, the laws of counterpoint were no longer held sacred. The old paths were forsaken; and those who essayed to walk in the new wandered vaguely, hither and thither, in search of an ideal, as yet but very imperfectly conceived, in pursuit of which they laboured on, through many weary years, cheered by very inadequate results, and little dreaming of the effect their work was fated to exercise upon generations of musicians then unborn. A long and dreary period succeeded, during which no work of any lasting reputation was produced: for, the Masses of Carissimi, Colonna, and the best of their contemporaries, though written in solemn earnest, and interesting enough when regarded as attempts at a new style, bear no comparison with the compositions of the preceding epoch; while those arranged by Benevoli (1602–1672) and the admirers of his School, for combinations of four, six, eight, and even twelve distinct Choirs, were forgotten, with the occasions for which they were called into existence. Art was passing through a transitional phase, which must needs be left to work out its own destiny in its own way. The few faithful souls who still clung to the traditions of the Past were unable to uphold its honours: and, with Gregorio Allegri, in 1652, the 'School of Palestrina' died out. Yet, not without hope of revival. The laws which regulated the composition of the Polyphonic Mass are as intelligible, to-day, as they were three hundred years ago; and it needs but the fire of living Genius to bring them, once more, into active operation, reinforced by all the additional authority with which the advancement of Modern Science has, from time to time, invested them.

Before quitting this part of our subject, for the consideration of the later Schools, it is necessary that we should offer a few remarks upon the true manner of singing Masses, such as those of which we have briefly sketched the history: and, thanks to the traditions handed down, from generation to generation, by the Pontifical Choir, we are able to do so with as little danger of misinterpreting the ideas of Palestrina, or Anerio, as we should incur in dealing with those of Mendelssohn, or Sterndale Bennett.

In the first place, it is a mistake to suppose that a very large body of Voices is absolutely indispensable to the successful rendering, even of very great works. On ordinary occasions, no more than thirty-two singers are present in the Sistine Chapel—eight Sopranos, and an equal number of Altos, Tenors, and Basses: though, on very high Festivals, their number is sometimes nearly doubled. The vocal strength must, of course, be proportioned to the size of the building in which it is to be exercised: but, whether it be great, or small, it must, on no account, be supplemented by any kind of instrumental accompaniment whatever. Every possible gradation of tone, from the softest imaginable whisper, to the loudest forte attainable without straining the Voice, will be brought into constant requisition. Though written, always, either with a plain signature, or with a single flat after the clef, the music may be sung at any pitch most convenient to the Choir. The time should be beaten in minims; except in the case of 3-1, in which three semibreves must be counted in each bar. The Tempo—of which no indication is ever given, in the old part-books will vary, in different movements, from about ![]() = 50 to

= 50 to ![]() = 120. On this point, as well as on the subject of pianos and fortes, and the assignment of certain passages to Solo Voices, or Semi-chorus, the leader must trust entirely to the dictates of his own judgment. He will, however, find the few simple rules to which we are about to direct his attention capable of almost universal application; based, as they are, upon the important relation borne by the music of the Mass to the respective offices of the Priest, the Choir, and the Congregation. To the uninitiated, this relation is not always very clearly intelligible. In order to make it so, and to illustrate, at the same time, the principles by which the Old Masters were guided, we shall accompany our promised hints by a few words explanatory of the functions performed by the Celebrant, and his Ministers, during the time occupied by the Choir in singing the principal movements of the Mass—functions, the right understanding of which is indispensable to the correct interpretation of the music.

= 120. On this point, as well as on the subject of pianos and fortes, and the assignment of certain passages to Solo Voices, or Semi-chorus, the leader must trust entirely to the dictates of his own judgment. He will, however, find the few simple rules to which we are about to direct his attention capable of almost universal application; based, as they are, upon the important relation borne by the music of the Mass to the respective offices of the Priest, the Choir, and the Congregation. To the uninitiated, this relation is not always very clearly intelligible. In order to make it so, and to illustrate, at the same time, the principles by which the Old Masters were guided, we shall accompany our promised hints by a few words explanatory of the functions performed by the Celebrant, and his Ministers, during the time occupied by the Choir in singing the principal movements of the Mass—functions, the right understanding of which is indispensable to the correct interpretation of the music.

High Mass—preceded, on Sundays, by the Plain Chaunt Asperges me—begins, on the part of the Celebrant and Ministers, by the recitation, in a low voice, of the Psalm, Judica me Deus, and the Confiteor; on that of the Choir, by the chaunting, from the Gradual, of the Introit, appointed for the day. [See Introit.]

From the Plain Chaunt Introit, the Choir proceed, at once, to the Kyrie; and this transition from the severity of the Gregorian melody to the pure harmonic combinations of Polyphonic Music is one of the most beautiful that can be imagined. The Kyrie is always sung slowly, and devoutly (![]() = 56–66), with the tenderest possible gradations of light and shade. The Christe—also a slow movement—may often be entrusted, with good effect, to Solo Voices. The second Kyrie is generally a little more animated than the first, and should be taken in a quicker time (

= 56–66), with the tenderest possible gradations of light and shade. The Christe—also a slow movement—may often be entrusted, with good effect, to Solo Voices. The second Kyrie is generally a little more animated than the first, and should be taken in a quicker time (![]() = 96–112). The Kyrie of Palestrina's Missa brevis is one of the most beautiful in existence, and by no means difficult to sing, since the true positions of the crescendi and diminuendi can scarcely be mistaken. [See Kyrie.]

= 96–112). The Kyrie of Palestrina's Missa brevis is one of the most beautiful in existence, and by no means difficult to sing, since the true positions of the crescendi and diminuendi can scarcely be mistaken. [See Kyrie.]

While the Choir are singing these three movements, the Celebrant, attended by the Deacon, and Subdeacon, ascends to the Altar, and, having incensed it, repeats the words of the Introit, and Kyrie, in a voice audible to himself and his Ministers alone. On the cessation of the music, he intones, in a loud voice, the words, Gloria in excelsis Deo, to a short Plain Chaunt melody, varying with the nature of the different Festivals, and given, in full, both in the Missal, and the Gradual. [See Intonation.] This Intonation, which may be taken at any pitch conformable to that of the Mass, is not repeated by the Choir, which takes up the strain at Et in terra pax.

The first movement of the Gloria is, in most cases, a very jubilant one (![]() = 100–120): but, the words adoramus te, and Jesu Christe, must always be sung slowly, and softly (

= 100–120): but, the words adoramus te, and Jesu Christe, must always be sung slowly, and softly (![]() = 50–60); and, sometimes, the Gratias agimus, as far as gloriam tuam, is taken a shade slower than the general time, in accordance with the spirit of the Rubric which directs, that, at these several points, the Celebrant and Ministers shall uncover their heads, in token of adoration. After the word, Patris, a pause is made. The Qui tollis is then sung, Adagio (

= 50–60); and, sometimes, the Gratias agimus, as far as gloriam tuam, is taken a shade slower than the general time, in accordance with the spirit of the Rubric which directs, that, at these several points, the Celebrant and Ministers shall uncover their heads, in token of adoration. After the word, Patris, a pause is made. The Qui tollis is then sung, Adagio (![]() = 56–66); with ritardandi at miserere nobis, and suscipe deprecationem nostrum. At the Quoniam tu solus, the original quick time is resumed, and carried on, with ever increasing spirit, to the end of the movement; except that the words, Jesu Christe, are again delivered slowly, and softly, as before. The provision made, in the Missa Papæ Marcelli, for the introduction of these characteristic changes of Tempo, is very striking, and points clearly to the antiquity of the custom.

= 56–66); with ritardandi at miserere nobis, and suscipe deprecationem nostrum. At the Quoniam tu solus, the original quick time is resumed, and carried on, with ever increasing spirit, to the end of the movement; except that the words, Jesu Christe, are again delivered slowly, and softly, as before. The provision made, in the Missa Papæ Marcelli, for the introduction of these characteristic changes of Tempo, is very striking, and points clearly to the antiquity of the custom.

The Celebrant now recites the Collects for the day; the Subdeacon sings the Epistle, in a kind of Monotone, with certain fixed Inflexions; the Choir sings the Plain Chaunt Gradual, followed by the Tract, or Sequence, according to the nature of the Festival; and the Deacon sings the Gospel, to its own peculiar Tone. [See Gradual; Tract; Sequence; Accents.] If there be a Sermon, it follows next in order: if not, the Gospel is immediately followed by the Creed.

The words, Credo in unum Deum, are intoned, by the Celebrant, to a few simple notes of Plain Chaunt, which never vary—except in pitch—and which are to be found both in the Gradual, and the Missal. [See Intonation.] The Choir continue, Patrem omnipotentem, in a moderate Allegro, more stately than that of the Gloria (![]() = 96–112), and marked by the closest possible attention to the spirit of the text. A ritardando takes place at Et in unum Dominum; and the words, Jesum Christum, are sung as slowly, and as softly, as in the Gloria, (

= 96–112), and marked by the closest possible attention to the spirit of the text. A ritardando takes place at Et in unum Dominum; and the words, Jesum Christum, are sung as slowly, and as softly, as in the Gloria, (![]() = 50–60). The quicker time is resumed at Filium Dei; and a grand forte may generally be introduced, with advantage, at Deum de Deo, and continued as far as facto sunt—as in Palestrina's Missa 'Assumpta est Maria,' and many others. After the words, de coelis, a long pause takes place, while the Congregation kneel. The Et incarnatus est then follows, in the form of a soft and solemn Adagio (

= 50–60). The quicker time is resumed at Filium Dei; and a grand forte may generally be introduced, with advantage, at Deum de Deo, and continued as far as facto sunt—as in Palestrina's Missa 'Assumpta est Maria,' and many others. After the words, de coelis, a long pause takes place, while the Congregation kneel. The Et incarnatus est then follows, in the form of a soft and solemn Adagio (![]() = 54–63), interrupted, after factus est, by another pause, long enough to enable the people to rise from their knees in silence. The Crucifixus is also a slow movement; the return to the original Allegro being deferred until the Et resurrexit. In the Missa Papæ Marcelli, and many other very fine ones, this part of the Credo is written for four solo voices; but, the necessity for an acceleration of the time at the Et resurrexit is very strongly marked. In the beautiful Missa brevis already mentioned, the Basses lead off the Et resurrexit, in quick time, while the Soprano, and Alto, are still engaged in finishing a ritardando—a very difficult, though by no means uncommon point, which can only be overcome by very careful practice.

= 54–63), interrupted, after factus est, by another pause, long enough to enable the people to rise from their knees in silence. The Crucifixus is also a slow movement; the return to the original Allegro being deferred until the Et resurrexit. In the Missa Papæ Marcelli, and many other very fine ones, this part of the Credo is written for four solo voices; but, the necessity for an acceleration of the time at the Et resurrexit is very strongly marked. In the beautiful Missa brevis already mentioned, the Basses lead off the Et resurrexit, in quick time, while the Soprano, and Alto, are still engaged in finishing a ritardando—a very difficult, though by no means uncommon point, which can only be overcome by very careful practice.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Another change of time is sometimes demanded, at Et in Spiritum Sanctum: but, more generally, the Allegro continues to the end of the movement; interrupted only at the words simul adoratur, which are always sung Adagio, and pianissimo, while the Celebrant and Ministers uncover their heads.

The Credo is immediately followed by the Plain Chaunt Offertorium for the day. But, as this is too short to fill up the time occupied by the Celebrant in incensing the Oblations, and saying, secreto, certain appointed Prayers, it is usually supplemented, either by a Motet, or a grand Voluntary on the Organ. [See Motet; Offertorium.] This is followed by the Versicle and Response called the Sursum corda, and the Proper Preface, at the end of which a Bell is rung, and the Sanctus is taken up by the Choir.

The Sanctus is invariably a Largo, of peculiar solemnity (![]() = 56–72). Sometimes, as in Palestrina's very early Mass, Virtute magna, the Pleni sunt coeli is set for Solo Voices. Sometimes, it is sung in chorus, but in a quicker movement, as in the same Composer's Missa Papæ Marcelli, and Æterna Christi munera—involving, in the last-named Mass, a difficulty of the same kind as that which we have already pointed out in the Et resurrexit of the Missa Brevis. The Osanna, though frequently spirited, must never be a noisy movement. In the Missa brevis, so often quoted, it is continuous with the rest of the Sanctus, and clearly intended to be sung pianissimo—an extremely beautiful idea, in perfect accordance with the character of this part of the Service, during which the Celebrant is proceeding, secreto, with the Prayers which immediately precede the Consecration of the Host. After the Elevation—which takes place in silence—the Choir begin the Benedictus, in soft low tones, almost always entrusted to Solo Voices. The Osanna, which concludes the movement, is, in the great majority of cases, identical with that which follows the Sanctus. The Pater noster is sung, by the Celebrant, to a Plain Chaunt melody, contained in the Missal. After its conclusion, the Choir sings the last movement of the Mass—the Agnus Dei—while the Celebrant is receiving the Host. The first division of the Agnus Dei may be very effectively sung by Solo Voices, and the second, in subdued chorus (

= 56–72). Sometimes, as in Palestrina's very early Mass, Virtute magna, the Pleni sunt coeli is set for Solo Voices. Sometimes, it is sung in chorus, but in a quicker movement, as in the same Composer's Missa Papæ Marcelli, and Æterna Christi munera—involving, in the last-named Mass, a difficulty of the same kind as that which we have already pointed out in the Et resurrexit of the Missa Brevis. The Osanna, though frequently spirited, must never be a noisy movement. In the Missa brevis, so often quoted, it is continuous with the rest of the Sanctus, and clearly intended to be sung pianissimo—an extremely beautiful idea, in perfect accordance with the character of this part of the Service, during which the Celebrant is proceeding, secreto, with the Prayers which immediately precede the Consecration of the Host. After the Elevation—which takes place in silence—the Choir begin the Benedictus, in soft low tones, almost always entrusted to Solo Voices. The Osanna, which concludes the movement, is, in the great majority of cases, identical with that which follows the Sanctus. The Pater noster is sung, by the Celebrant, to a Plain Chaunt melody, contained in the Missal. After its conclusion, the Choir sings the last movement of the Mass—the Agnus Dei—while the Celebrant is receiving the Host. The first division of the Agnus Dei may be very effectively sung by Solo Voices, and the second, in subdued chorus (![]() = 50–72), with gentle gradations of piano, and pianissimo, as in the Kyrie. When there is only one movement, it must be sung twice; the words dona nobis pacem being substituted, the second time, for miserere nobis. The Agnus Dei of Josquin's Missa 'L'Homme armé' is in three distinct movements.

= 50–72), with gentle gradations of piano, and pianissimo, as in the Kyrie. When there is only one movement, it must be sung twice; the words dona nobis pacem being substituted, the second time, for miserere nobis. The Agnus Dei of Josquin's Missa 'L'Homme armé' is in three distinct movements.

The Choir next sings the Plain Chaunt Communio, as given in the Gradual. The Celebrant recites the Prayer called the Post-Communion. The Deacon sings the words, 'Ite, missa est,' from which the Service derives its name. And the Rite concludes with the Domine salvum fac, and Prayer for the reigning Sovereign.

The Ceremonies we have described are those peculiar to High or Solemn Mass. When the Service is sung by the Celebrant and Choir, without the assistance of a Deacon and Subdeacon, and without the use of Incense, it is called a Missa cantata, or Sung Mass. Low Mass is said by j the Celebrant, alone, attended by a single Server. I According to strict usage, no music whatever is admissible, at Low Mass: but, in French and German village Churches, and, even in those of Italy, it is not unusual to hear the Congregations sing Hymns, or Litanies, appropriate to the occasion, though not forming part of the Service. Under no circumstances can the duties proper to the Choir, at High Mass, be transferred to the general Congregation.

It is scarcely necessary to say, that the music of every Mass worth singing will naturally demand a style of treatment peculiar to itself; especially with regard to the Tempi of its different movements. A modern editor tells us that more than four bars of Palestrina should never be sung, continuously, in the same time.[6] This is, of course, an exaggeration. Nevertheless, immense variety of expression is indispensable. Everything depends upon it: and, though the leader will not always find it easy to decide upon the best method, a little careful attention to the points we have mentioned will, in most cases, enable him to produce results very different from any that are attainable by the hard dry manner which is too often supposed to be inseparable from the performance of antient figured music.

Our narrative was interrupted, at a transitional period, when the grand old mediæval style was gradually dying out, and a newer one courageously struggling into existence, in the face of difficulties which, sometimes, seemed insurmountable. We resume it, after the death of the last representative of the old régime, Gregorio Allegri, in the year 1652.

The most remarkable Composers of the period which we shall designate as the Seventh Epoch in the history of the vocal Mass—comprising the latter part of the Seventeenth Century, and the earlier years of the Eighteenth—were, Alessandro Scarlatti, Leo, and Durante: men whose position in the chronicles of Art is rendered somewhat anomalous, though none the less honourable, by the indisputable fact, that they all entertained a sincere affection for the older School, while labouring, with all their might, for the advancement of the newer. It was, undoubtedly, to their love for the Masters of the Sixteenth Century that they owed the dignity of style which constitutes the chief merit of their compositions for the Church: but, their real work lay in the direction of instrumental accompaniment, for which Durante, especially, did more than any other writer of the period. His genius was, indeed, a very exceptional one. While others were content with cautiously feeling their way, in some new and untried direction, he boldly started off, with a style of his own, which gave an extraordinary impulse to the progress of Art, and impressed its character so strongly upon the productions of his followers, that he has been not unfrequently regarded as the founder of the modern Italian School. Whatever opinion may be entertained on that point, it is certain that the simplicity of his melodies tended, in no small degree, to the encouragement of those graces which now seem inseparable from Italian Art; while it is equally undeniable that the style of the Cantata, which he, no less than Alessandro Scarlatti, held in the highest estimation, exercised an irresistible influence over the future of the Mass.

The Eighth Epoch is represented by one single work, of such gigantic proportions, and so exceptional a character, that it is impossible, either to class it with any other, or to trace its pedigree through any of the Schools of which we have hitherto spoken. The artistic status of John Sebastian Bach's Mass in B minor,—produced in the year 1733—only becomes intelligible, when we consider it as the natural result of principles, inherited through a long line of masters, who bequeathed their musical acquirements, from father to son, as other men bequeath their riches: principles, upon which rest the very foundations of the later German Schools. Bearing this in mind, we are not surprised at finding it free from all trace of the older Ecclesiastical traditions. To compare it with Palestrina's Missa Papæ Marcelli—even were such a perversion of criticism possible—would be as unfair, to either side, as an attempt to judge the master pieces of Rembrandt by the standard of Fra Angelico. The two works are not even coincident in intention—for, it is almost impossible to believe that the one we are now considering can ever have been seriously intended for use as a Church Service. Unfitted for that purpose, as much by its excessive length, as by the exuberant elaboration of its style, and the overwhelming difficulty of its execution, it can only be consistently regarded as an Oratorio—so regarded, it may be safely trusted to hold its own, side by side with the greatest works of the kind that have ever been produced, in any country, or in any age. [See Oratorio.] Its masterly and exhaustively developed Fugues; its dignified Choruses, relieved by Airs, and Duets, of infinite grace and beauty; the richness of its instrumentation, achieved by means which most modern composers would reject as utterly inadequate to the least ambitious of their requirements; above all, the colossal proportions of its design—these, and a hundred other characteristics into which we have not space to enter, entitle it to rank as one of the finest works, if not the very finest, that the great Cantor of the Thomas-Schule has left, as memorials of a genius as vast as it was original. Whether we criticise it as a work of Art, of Learning, or of Imagination, we find it equally worthy of our respect. It is, moreover, extremely interesting, as an historical monument, from the fact, that, in the opening of its Credo, it exhibits one of the most remarkable examples on record of the treatment of an antient Canto fermo with modern harmonies, and an elaborate orchestral accompaniment. [See Intonation.] Bach often shewed but little sympathy with the traditions of the Past. But, in this, as in innumerable other instances, he proved his power of compelling everything he touched to obey the dictates of his indomitable will.

While the great German composer was thus patiently working out his hereditary trust, the disciples of the Italian School were entering upon a Ninth Epoch—the last which it will be our duty to consider, since its creative energy is, probably, not yet exhausted—under very different conditions, and influenced by principles which led to very different results. If we have found it necessary to criticise Bach's wonderful production as an Oratorio, still more necessary is it, that we should describe the Masses of this later period as Sacred Cantatas. Originating, beyond all doubt, with Durante; treated with infinite tenderness by Pergolesi and Jomelli; endowed with a wealth of graces by the genius of Haydn and Mozart; and still farther intensified by the imaginative power of Beethoven and Cherubini; their style has steadily kept pace, step by step, with the progress of modern music; borrowing elasticity from the freedom of its melodies, and richness from the variety of its instrumentation; clothing itself in new and unexpected forms of beauty, at every turn; yet, never aiming at the expression of a higher kind of beauty than that pertaining to earthly things, or venturing to utter the language of devotion in preference to that of passion. In the Masses of this æra we first find the individuality of the Composer entirely dominating over that of the School—if, indeed, a School can be said to exist, at all, in an age in which every Composer is left free to follow the dictates of his own unfettered taste. It is impossible to avoid recognising, in Haydn's Masses, the well-known features of 'The Creation' and 'The Seasons'; or, in those of Mozart, the characteristic features of his most delightful Operas. Who, but the Composer of 'Dove sono i bei momenti,' or, the Finales to Don Giovanni, and the Flauto Magico, could ever have imagined the Agnus Dei of the First Mass, or the Gloria of the Second? Still more striking is the identity of thought which assimilates Beethoven's Missa solemnis to some of the greatest of his sæcular works; notwithstanding their singular freedom from all trace of mannerism. Mozart makes himself known by the refinement of his delicious phrases: Beethoven, by the depth of his dramatic instinct—a talent which he never turned to such good account as when working in the absence of stage accessories. We are all familiar with that touching episode in the 'Battle Symphony,' wherein the one solitary Fifer strives to rally his scattered comrades by playing Malbrook s'en va-t-en guerre—a feat, which, by reason of the thirst and exhaustion consequent upon his wound, he can only accomplish in a minor key. No less touching, though infinitely more terrible, is that wonderful passage of Drums and Trumpets, in the Dona nobis pacem of the Mass in D, intended to bring the blessings of Peace into the strongest possible relief, by contrasting them with the horrors of War.

[ W. S. R. ]

Appendix:

Since the article on Byrd was written for this Appendix, the British Museum has acquired a aet of four part- books (Superius, Medius, Tenor, Bassus) of the second edition (1610) of Byrd's Gradualia. This copy is interleaved with the corresponding parts of all three of Byrd's Masses, viz. those for five, four, and three voices. It is possible that they were published in this form. The part-books are in admirably fresh condition, and have every appearance of being in the same state as when they were first published, but on the other hand the paper on which the masses are printed is different from that of the rest of the work, and the register signatures show that they are not originally intended to form part of the Gradualia.

The account of the Mass for five voices in vol. ii. p. 230 should be corrected by the article on Byrd in this volume, p. 573b. In Father Morris's 'Life of Father William Weston' ('The Troubles of our Catholic Forefathers,' second series, 1875, pp. 142–5) will be found some fresh information about Byrd, though Dr. Rimbault's old mistakes are again repeated there. Father Morris has found several allusions to Byrd as a recusant in various lists preserved in the State Papers (Domestic Series, Elizabeth, cxlvi. 137, cli. ii, clxvii. 47, cxcii. 48), and in the following interesting passage in Father Weston's Autobiography, describing his reception at a house which is identified as being that of a certain Mr. Bold: 'We met there also Mr. Byrd, the most celebrated musician and organist of the English nation, who had been formerly in the Queen's Chapel, and held in the highest estimation; but for his religion he sacrificed everything, both his office and the Court and all those hopes which are nurtured by such persons as pretend to similar places in the dwellings of princes, as steps towards the increasing of their fortunes.' This was written in the summer of 1586. The recently published Sessions Rolls of the County of Middlesex show that true bills 'for not going to church, chapel, or any usual place of common prayer' were found against 'Juliana Birde wife of William Byrde' of Harlington on June 28, 1581; Jan. 19, April 2, 1582; Jan. 18, April 15, Dec. 4, 1583; March 27, May 4, Oct. 5, 1584; March 31, July 2, 1585; and Oct. 7, 1586. A servant of Byrd's, one John Reason, was included in all these indictments, and Byrd himself was included in that of Oct. 7, 1586, and without his wife or his servant a true bill was found against him on April 7, 1592, at which date he is still described as of Harlington. It is very curious that if, as Father Weston was informed, he had sacrificed his place at Court, there should be no mention of it in the Chapel Royal Cheque Book; but his subsequent dealings at Stondon with Mrs. Shelley show that he must have been protected by some powerful influence. To this he seems to allude in the dedication of the Gradualia to the Earl of Northampton.[ W. B. S. ]

- ↑ The accidentals in this, and the following examples, are all supplied in accordance with the laws of Cantus fictus.

- ↑ Dodecachordon, p. 445, ed. 1547.

- ↑ It is difficult to understand why Palestrina should have given it this name, ten years after the death of Pope Marcellus II. The reader Trill find the whole subject exhaustively discussed, in the pages of Baini (tom. 1. sec. 2. cap. 1 et seq.)

- ↑ The preface to a recent German edition of the Missa Papæ Marcelli erroneously describes the work as written in the Mixolydian Mode. The Crucifixus, and Benedictus, are undoubtedly Mixolydian; but, the Mass itself is, beyond all question, written in the Fourteenth, or Hypoionian Mode, to the tonality, compass, and cadences of which It conforms, throughout.

- ↑ One of these, Tu es Petrus, was printed, for the first time, in 1869, in Schrem's continuation of Proske's 'Musica Divina' (Ratisbon, Fr. Pustet).

- ↑ The only other Composer, antient, or modern, with regard to whose works such a remark could have been hazarded, is Chopin—the unfettered exponent of the wildest dreams of modern romanticism. So strangely does experience prove that 'there is nothing new under the Sun'!