A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Organum

ORGANUM (equivalent to Diaphonia; and, though less exactly, to Discantus). It is impossible to ascertain the date at which Plain Chaunt was first harmonised; and equally so, to discover the name of the Musician who first sang it in harmony. We know, however, that the primitive and miserably imperfect Counterpoint with which it was first accompanied was called Organum; and we have irrefragable proof that this Organum was known at least as early as 880; for Scotus Erigena, who died about that date, speaks of it in his treatise 'De divinanatura,' in such terms as to leave no doubt as to its identity, and to show clearly that it was sufficiently well understood at the time he wrote to serve as a familiar illustration.[1]

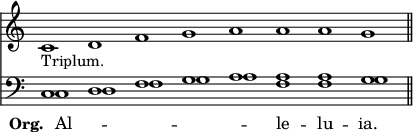

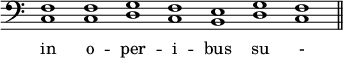

No mediæval writer has given us the slightest hint as to the etymology of the word; but most modern historians are agreed that the prima facie derivation is, in all probability, the true one. When Organs were first introduced into the Services of the Church—probably in the 7th century, but certainly not later than the middle of the 8th[2]—it must have been almost impossible for an Organist, playing with both hands, to avoid sounding concordant intervals simultaneously: and, when once the effects thus produced were imitated in singing, the first step towards the invention of Polyphony was already accomplished. This granted, nothing could be more natural than that the Instrument should lend its name to the new style of singing it had been the accidental means of suggesting; or that the Choristers who practised that method of vocalisation should be called Organizers, though we well know that they sang without any instrumental accompaniment whatever, and that they were held in high estimation for their readiness in extemporising such harmony as was then implied by the term Organum. A Necrologium of the 13th century, quoted by Du Cange, ordains, in one place, that 'the Clerks who organize the "Alleluia," in two, three, or four parts, shall receive six pence'; and in another, that 'the Clerks who assist in the Mass shall have two pence, and the four Organizers of the "Alleluia" two pence each.' This 'organization of the Alleluia' meant nothing more than the addition of one single Third, which was sung below the penultimate note of a Plain Chaunt Melody, in order to form a Cadence. When this Cadence was in two parts only, it was sung by two Tenors; when a third part was added, it was sung an Octave above the Canto fermo, by the Voice called 'Triplum' (whence our word Treble); the fourth part, a Quadruplum, was added in the Octave above the Organum, thus—

In Two Parts.

In Three Parts.

In Four Parts.

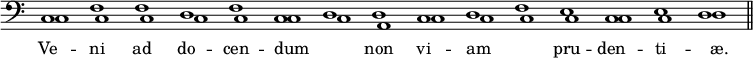

After a time the single Third gave place to a continuous Organum. The earliest writer who gives us any really intelligible account of the method of constructing such a Harmony is Hucbaldus, a Monk of S. Amand sur l'Elnon, in Flanders, who died at a very advanced age in the year 930, and whose attempts to improve the Notation of Plain Chaunt have already been described at page 469 of the present volume. It is noticeable that, though the multilinear Stave proposed by this learned Musician is mentioned as his own invention, he prefers no claim to be regarded as the originator of the new method of Singing, but speaks of it as a practice 'which they commonly call organization.' He understood it, however, perfectly; and gives very clear rules for its construction. From these we learn that, though it is perfectly lawful to sing a Plain Chaunt Melody either in Octaves or doubled Octaves, this method cannot fairly be said to constitute a true Organum, which should be sung either in Fourths or Fifths as shown in the following examples.

In Fourths.

In Fifths.

When four Voices are used, either the Fourths or the Fifths may be doubled.

These two methods, in which no mixture of Intervals is permitted, have been called by some modern historians Parallel-Organum, in contradistinction to another kind, in which the use of Seconds and Thirds is permitted, on condition that two Thirds are not allowed to succeed one another. Hucbald describes this also as a perfectly lawful method, provided the Seconds and Thirds are introduced only for the purpose of making the Fourths move more regularly.

To the modern student this stern prohibition of even two Consecutive Thirds, where any number of Consecutive Fifths or Octaves are freely permitted, is laughable enough; but our mediæval ancestors had some reason on their side. In the days of Hucbald, the Mathematics of Music were in a very unsatisfactory condition. He himself had a very decided preference for the Greek Scales; and even Guido d'Arezzo, who lived a century later, based his theory on the now utterly obsolete Pythagorean Section of the Canon, which divided the Perfect Fourth (Diatessaron) into two Greater Tones and a Limma, making no mention whatever of the more natural system of Ptolemy, which resolved it into a Greater Tone, a Lesser Tone, and a Diatonic Semitone. The result of this mistaken theory was, that every Major Third in the Natural Scale was tuned exactly a Comma too sharp, and every Minor Third a Comma too flat. Were this method of Intonation still practised, some of us might, perhaps, desire to hear as few Thirds as possible.

Neither S. Odo of Cluni, nor any other writer of the age immediately succeeding that of Hucbald, throws any light upon the subject sufficiently important to render it necessary that we should discuss it in detail; but Guido d'Arezzo's opinions are too interesting to be passed over in silence. He objects to the use of united Fourths, and Fifths, in an Organum of three parts, on account of its disaafreeable harshness.

In place of this he proposes to leave out the upper part, which in this example is nothing more than a reduplication of the Organum—the Canto fermo being assigned to the middle Voice, and to sing the two lower parts only: or, better still, to substitute an improved method, which, from the closeness of the parts to each other as they approach the conclusion of the Melody, he calls Occursus.

After the death of Guido the subject was treated, more or less fully, by Franco of Cologne, Walter Odington, Marchetto de Padova, Philippus de Vitriaco, Joannes de Muris, Prodoscimus de Beldomandis, and many other writers, each of whom contributed something towards the general stock of knowledge, and suggested some improvement upon the usual praxis: but the next critical stage was only reached when the Sixth became recognised as an Interval of greater practical importance than either the fourth or the Fifth. Joannes Tinctoris (1434–1520) saw this very clearly; and gives the following example of a Melody accompanied in Sixths and Octaves.

But, before the death of Joannes Tinctoris, these successions of Sixths had already merged into the well-known Faux-bourdon, and Organum into Counterpoint; though the fact that Organizers still held their ground is sufficiently proved by the allusions made to them in the Minstrel-Laws of Eberhard von Minden, in 1404, and even in a document preserved at Toledo, of as late date as 1566, in which distinct mention is made of the 'musica quæ organica dicitur.'

[ W. S. R. ]