A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Notation

NOTATION (Lat. Notatio; Fr. Sémiographie; Germ. Notirang, Notenschrift, Tonschrift). The Art of expressing musical ideas in writing.

Apart from its intrinsic value, the history of Notation derives much collateral importance from the light it throws upon that of Music, generally. From its earliest infancy, the Art has known no period of absolute stagnation. Incessant progress has long been recognised as a fundamental law of its existence; and a more or less extensive change in its written language has been naturally demanded, at each successive stage of its development. This conceded, we can scarcely wonder that the study of such changes should materially aid our attempts to trace the story of its inner life.

Three different systems of Notation have been accepted as sufficient for all practical purposes, at different periods. In very early times, when Melody was simple, and Harmony unknown, musical sounds were represented by the Letters of the Alphabet. Many centuries later, these were superseded by a species of Hieratic Character, the components of which were known to the Monks of the Middle Ages under the name of Neumæ. The final stage of perfection was reached, when these last were developed into the characters now called Notes, and written upon the Lines and Spaces of the Stave.

The Greeks made use of Uncial Letters, intermixed occasionally with a few Minusculæ, and written in an endless variety of different positions upright, inverted, lying on the right or left side, divided in half, placed side by side, and otherwise grouped into some hundred and twenty well-marked combinations, which, with more than a thousand minor variations, have been so clearly described by Alypius, Aristides Quintilianus, and other Hellenic writers, that, could we but obtain authentic copies of the Hymns of Pindar, or the Choruses of Sophocles, we should probably find them easier to decypher than many mediæval MSS.[1]

When Greece succumbed beneath the power of Western Europe, Roman Letters took the place of the more archaic forms, but with a different application; for, while the details of Greek Notation were designed with special reference to the division of the system into those peculiar Tetrachords which formed its most prominent characteristic, the Roman Letters were, at a very early period, applied, in alphabetical order, to the Degrees of the Scale—a much more simple arrangement, the value of which is too well known to need comment. Boëthius, writing in the 6th century, sanctioned the use of the first fifteen Letters of the Roman Alphabet, for certain special purposes. This number was afterwards reduced to seven—it is not easy to say by whom.[2] Tradition ascribes the first use of the lesser number to S. Gregory, but on very insufficient grounds; though the reactionary idea that he was unacquainted with the Alphabetical System, cannot for a moment be entertained.[3] It is certain that Letters were used, for many centuries, in the Notation of Plain Chaunt, in the West; just as the use of the Greek Characters was retained in the Ofiice-Books of the Eastern Church. After the 8th century, though they rarely appeared in writing, the Degrees of the Scale were still named after them. As symbols of these Degrees, they have never been discarded. Guido used them, in the 11th century, in connection with the Solmisation of the Hexachords; though their presence, as written characters, was then no longer needed. The first eight, indeed, lived on, in a certain way, until quite recent times, in the Tablature for the Lute, which always claimed a special method of its own. This, however, was an exceptional case. Long before the invention of the Stave, the system came virtually to an end: and, in our own day, it survives only in the nomenclature of our notes, and the employment of the F, C, and G Clefs. [See Hexachord, Tablature.]

Though wanting neither in clearness nor in certainty, this primitive system was marred, throughout all its changes, by one very serious defect. A mere collection of arbitrary signs, arranged in straight lines above the poetical text, it made no attempt to imitate, by means of symmetrical forms, the undulations of the Melody it represented. To supply this deficiency, a new system was invented, based upon an entirely different principle, and bringing into use an entirely new series of characters, of which we first find well-formed examples in the MSS. of the 8th century, though similar figures are believed to have been traced back as far as the 6th. These characters consisted of Points, Lines, Accents, Hooks, Curves, Angles, Retorted Figures, and a multitude of other signs, or [4]Neumæ, placed, more or less exactly, over the syllables to which they were intended to be sung, in such a manner as to indicate, by their proportionate distances above the text, the places in which the Melody was to rise or fall. Joannes de Muris mentions seven different species of Neumæ. A MS. preserved at Kloster Murbach describes seventeen. A still more valuable Codex, once belonging to the Monastery of S. Blasien, in the Black Forest, gives the names and figures of forty: and many curious forms are noticed in Fra Angelico Ottobi's Calliopea leghale (written in the latter half of the 14th century), and other similar works. The following were the forms most commonly used; though, of course, mediæval caligraphy varied greatly at different periods.

1. The Virga indicated a long single note, which was understood to be a high or a low one, according to the height of the sign above the text. A group of two was called a Bivirga, and one of three, a Trivirga—representing two and three notes respectively.

2. The Punctus indicated a shorter note, subject to the same rule of position, and of multiplication into the Bipunctus, and Tripunctus.

3. The Podatus represented a group of two notes, of which the second was the highest. Its figure varied considerably in different MSS.

4. The Clivis, Clinis, or Flexa, indicated a group of two notes, of which the second was the lowest. This, also, varied very much in form.

5. The Scandicus denoted a group of three ascending notes.

6. The Climdeus denoted three notes, descending.

7. The Cephalicus—sometimes identified with the Torculus—represented a group of three notes, of which the second was the highest.

8. The Flexa resupina—described by some writers as the Porrectus—indicated a group of three notes, of which the second was the lowest.

9. The Flexa strophica indicated three notes, of which the second was lower than the first, and the third a reiteration of the second.

10. The Quilisma was originally a kind of shake, or reiterated note; but in later times its meaning became almost identical with that of the Scandicus.

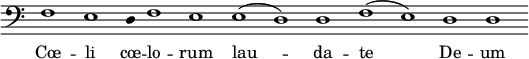

These, and others of less general importance—as the Ancus, Oriscus, Salicus, Pressus, Tramea, etc., etc.—were frequently combined into forms of great complexity, of which a great variety of examples, accurately figured, and minutely described, will be found in the works of Gerbert, P. Martini, Coussemaker, Kiesewetter, P. Lambillotte, Ambros, and the Abbé Raillard. Beyond all doubt, they were, originally, mere Accents, analogous to those of Alexandrian Greek, and intended rather as aids to declamation, than to actual singing: but, a more specific meaning was soon attached to them. They served to point out, not only the number of the notes which were to be sung to each particular syllable of the Poetry, but, in a certain sense, the manner in which they were to be treated. This was a most important step in advance; yet, the new system had also its defects. Less definite, as indications of pitch, than the Letters they displaced, the Neumæ did, indeed, shew at a glance the general conformation of the Melody they were supposed to illustrate, but entirely failed to warn the Singer whether the Interval by which he was expected to ascend, or descend, was a Tone, or a Semitone, or even a Second, Third, Fourth, or Fifth. Hence, their warmest supporters were constrained to admit, that, though invaluable as a species of memoria technica, and well fitted to recal a given Melody to a Singer who had already heard it, they could never—however carefully (curiose) they might be drawn enable him to sing a new or unknown Melody at sight. This will be immediately apparent from the following antient example, quoted by P. Martini in the first volume of his 'Storia di Musica':

Towards the close of the 8th century, we find certain small letters interspersed among the more usual Neumæ. In the celebrated 'Antiphonarium' of S. Gall[5]—an invaluable MS., which has long been received, on very weighty evidence, as a faithful transcript of the Antiphonary of S. Gregory—these small letters form a conspicuous feature in the Notation; and they are, beyond all doubt, the prototypes of our so-called 'Dynamic Signs,' the earliest recorded indications of Tempo and Expression. It is amusing to find our familiar forte foreshadowed by a little f (diminutive of fragor); and tenuto, or ben tenuto, by t, or bt (teneatur, or bene teneatur). A little c stands for celeriter (con moto); and other letters are used, which are interesting as signs of a growing desire for something more than an empty rendering of mechanical sounds. But, about the year 900,[6] a far greater improvement was brought into general use—an invention which contains within itself the germ of all that is most logical, and, practically, most enduring, in our present perfect system. The idea was very simple. A long red line, drawn horizontally across the parchment, formed the only addition to the usual scheme. All Neumæ, placed directly upon this line, were understood to represent the note F. Graver sounds were denoted by characters placed below, and more acute ones by others drawn above it. Thus, while the position of one note was absolutely fixed, that of others was rendered much more definite than heretofore.

The advantage of this new plan was so obvious, that a yellow line, intended to represent C, was soon added, at some little distance above the red cue. This quite decided the position of two notes; and, as it was evident that every note placed between the two lines must necessarily be either G, A, or B, the place of the others was no longer very difficult to determine.

In the plainer kind of MSS., written in black ink only, the letters F and C were placed at the beginning of their respective lines, no longer distinguishable by difference of colour; and thus arose our modern F and C Clefs, which, like the G Clef of later date, are really nothing more than conventional modifications of the old Gothic letters, transformed into a kind of technical Hieroglyphic, and passing through an infinity of changes, before arriving at the form now universally recognised.

Early in the 10th century, Hucbaldus, a Monk of S. Amand sur l'Elnon, in Flanders,[7] introduced a Stave consisting of a greater number of lines, and therefore more closely resembling, at first sight, our own familiar form, though in reality its principle was farther removed from that than the older system already described. The Lines themselves were left unoccupied. The syllables intended to be sung were written in the Spaces between them; and, in order to shew whether the Voice was to proceed by a Tone, or a Semitone, the letters T and S (for Tonus, and Semitonium) were written at the beginning of each, sometimes alone, but more frequently accompanied by other characters analogous to the signs used in the earlier Greek system, and connected with the machinery of the Tetrachords, which formed a conspicuous feature in Hucbald's teaching.

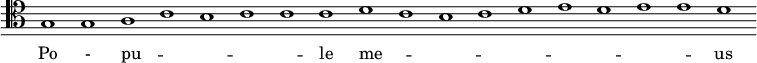

One great advantage attendant upon this system was, that by increasing the number of lines, it could be applied to a Scale of any extent, and even used for a number of Voices singing at the same time. Hucbaldus himself saw this; and has left us specimens of Discant, written in four different parts, which are easily distinguishable from each other by means of diagonal lines placed between the syllables. [See Organum; Part-writing.]

Not long after the time of Hucbaldus, we find traces of a custom—described by Vincenzo Galilei, in 1581, and afterwards, by Kircher—of leaving the Spaces vacant, and indicating the Notes by Points written upon the Lines only, the actual Degrees of the Scale being determined by Greek Letters placed at the end of the Stave.

The way was now fully prepared for the last great improvement; which, despite its incalculable importance, seems to us absurdly simple. It consisted in drawing two plain black Lines above the red and yellow ones which had preceded the broader Stave of Hucbald whose system soon fell into disuse and writing the Notes on alternate Lines and Spaces. The credit of this famous invention is commonly awarded to Guido d'Arezzo; but, though far from espousing the views of certain critics of the modern destructive school, who would have us believe that that learned Benedictine invented nothing at all, we cannot but admit, that, in this case, his claim is not altogether incontestable. His own words prove that he scrupled not to utilise the inventions of others when they suited his purpose. He may have done so here. We have shewn that both Lines and Spaces were used before his time, though not in combination. But this is not all. In an antient Office-Book—a highly interesting 'Troparium'—once used at Winchester Cathedral, and now preserved in the Bodleian Library at Oxford,[8] the Notes of the Plain Chaunt are written upon the alternate Lines and Spaces of a regular four-lined Stave. This precious MS. is generally believed to have been written during the reign of King Ethelred II, who died in 1016. The words Ut Ethelredum regem et exercitum Anglorum conservare digneris, inserted in the Litany, at fol. 18. B, certainly confirm this opinion. But a great part of the MS., including this paicicular Litany, is written in the old Notation, without the Stave; and sometimes both forms are found upon the same sheet. The subjoined fac-simile, for instance, shewing the places at which the Four-line Stave first makes its appearance in the volume, is taken from the middle of a page, the first part of which is filled with Music written upon the more antient system.

We do not pretend to under-rate the chronological difficulties which surround the question raised by this remarkable MS. Unless it was written at two different periods, two different methods would seem to have been used simultaneously in England at the opening of the 11th century, some considerable time before the appearance of Guido's 'Micrologus'—the most important of his works—which, it is tolerably certain, was not written before the year 1024, if even so early as that. Now a portion of the MS. was most certainly written before that date; and, if the evidence afforded by a close examination of its caligraphy may be trusted, there is every reason to believe that it was transcribed, throughout, by the same hand; in which case, we may fairly infer that the Stave of Four Lines was known and used in this country [App. p.732 "correct by reference to vol iii. p.692b"], at a period considerably anterior to its supposed invention in Italy. The advantages it presented, when made to serve as a vehicle for Neumæ, were obvious. It fixed their positions so clearly, that no doubt could now exist as to the exact notes they were intended to represent; and comparatively little difficulty was henceforth experienced, by the initiated, in reading Plain Chaunt at sight. A careful comparison of the subjoined example[9] with that given upon page 468 will illustrate the improvement it effected far more forcibly than any verbal description. The careful drawing of the Neumæ here sets all doubt at defiance.

So long as unisonous Plain Chaunt demanded no rhythmic ictus more strongly marked than that necessary for the correct pronunciation of the words to which it was adapted, this method was considered sufficiently exact to answer all practical purposes. But, the invention of Measured Chaunt discovered a new and pressing need. [See Musica Mensurata.] In the absence of a system capable of expressing the relative duration as well as the actual pitch of the notes employed, the accurate notation of Rhythmic Melody was impossible. No provision had as yet been made to meet this unforeseen contingency. We first find one proposed in the 'Ars Cantus mensurabilis' of Franco de Colonia, written, if we may trust the opinion of Fétis, and most of his critical predecessors, during the latter half of the 11th century—though Kiesewetter, rejecting the generally accepted date, argues in favour of the first half of the 13th. Franco's plan does not appear to have been an original one; but, rather, a compendium of the praxis in general use at the time in which he wrote: nevertheless, it is certain that we owe to him our first knowledge of the Time-Table. He it is, who first introduces to us the now familiar forms of the Large—described under the name of the Double Long—the Long, the Breve, and the Semibreve. The relationship of these new characters to preexistent Neumæ is plainly shewn by their outward form, the Large () and the Long (

![]() ) being self-evident developments of the Virga, ((Music characters)), while the Breve (

) being self-evident developments of the Virga, ((Music characters)), while the Breve (![]() ) and the Semibreve ((Music characters) or

) and the Semibreve ((Music characters) or ![]() ) are equally recognisable as the offspring of the Punctus (

) are equally recognisable as the offspring of the Punctus (![]() ). Franco makes each of the longer Notes equal, when Perfect, to two [App. p.732 "three"] Notes of the next lesser denomination; when Imperfect, to two only—the term Perfect being applied to the number Three, in honour of the Ever Blessed Trinity.[10] The Long was always Perfect, when followed by another Long, and the Breve, when followed by another Breve; but a Long preceded or followed by a Breve, or a Breve by a Semibreve, became, by Position, Imperfect. This simple rule was of immense importance; for it resulted in enabling the Composer to write in Triple or Duple Rhythm at will. The Semibreve, so long as it remained the shortest note in the series, was, of course, indivisible. But, after the invention of the Minim—either by Philippus de Vitriaco in the 13th century, or Joannes de Muris in the 14th—the Semibreve was also used, both in the Perfect and the Imperfect form; being equal, in the one case, to three, and, in the other, to two Minims. The Introduction of the Minim prepared the way for that of the Greater Semiminim, now known as the Crotchet; the Lesser Semiminim, afterwards called the Croma or Fusa, and in English the Quaver; and the Semicroma or Semifusa, answering to the modern Semiquaver. These three notes, like the Minim, were always Imperfect; and, for many centuries, they were used only after the manner of embellishments.

). Franco makes each of the longer Notes equal, when Perfect, to two [App. p.732 "three"] Notes of the next lesser denomination; when Imperfect, to two only—the term Perfect being applied to the number Three, in honour of the Ever Blessed Trinity.[10] The Long was always Perfect, when followed by another Long, and the Breve, when followed by another Breve; but a Long preceded or followed by a Breve, or a Breve by a Semibreve, became, by Position, Imperfect. This simple rule was of immense importance; for it resulted in enabling the Composer to write in Triple or Duple Rhythm at will. The Semibreve, so long as it remained the shortest note in the series, was, of course, indivisible. But, after the invention of the Minim—either by Philippus de Vitriaco in the 13th century, or Joannes de Muris in the 14th—the Semibreve was also used, both in the Perfect and the Imperfect form; being equal, in the one case, to three, and, in the other, to two Minims. The Introduction of the Minim prepared the way for that of the Greater Semiminim, now known as the Crotchet; the Lesser Semiminim, afterwards called the Croma or Fusa, and in English the Quaver; and the Semicroma or Semifusa, answering to the modern Semiquaver. These three notes, like the Minim, were always Imperfect; and, for many centuries, they were used only after the manner of embellishments.

Originally, the notes of Measured Chaunt were entirely black: but, after a time, red notes were intermixed with them, on condition—as Morley tells us—of losing one-fourth of their value. They do not, however, appear to have remained very long in use, or to have been, at any time, extensively employed. About the year 1370 both the black and red forms fell gradually into disuse; their place being supplied by white notes, with square or lozenge-shaped heads, which seem to have made their earliest appearance in France, though they were first brought into general notice by the leaders of the great Flemish School. The figures of these notes, and their corresponding rests, given in one of the earliest works on Music ever issued from the press—the 'Practica musicæ' of Franchinus Gafurius, printed at Milan, in 1496—differed little from the forms retained in use until the close of the 16th century.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Large. Long. Breve. Minim. <%? ^gor . miuim - Croma.

Perfect Large Rest. Imperfect Perfect Large Long Rest. Rest. Imperfect Long Rest. Breve Rest. Semibreve Rest.

Minim Rest, or Suspirium. Greater Semiminim Rest, or Semisuspirium. Croma Rest. Semicroma Rest.

White-headed notes were always written upon a Stave of Five Lines. Traces of this Stave are found, as early as the beginning of the 13th century, in a MS. Tract, 'De speculatione musices,' by Walter Odington, a Monk of Evesham in Worcestershire, whose work, now preserved at Cambridge, is only second in value to that of Franco; but it does not seem to have been universally recognised until after the invention of printing. A few square black notes were occasionally interspersed among the white ones, on conditions analogous to those attached to the employment of red notes among black ones at an earlier epoch—the loss of a third of their value when Perfect, and a fourth when Imperfect. We shall find it necessary to describe the office of these black notes more particularly, when speaking of the Points of Augmentation, Division, and Alteration. The lesser Semiminim, Croma, and Semicroma always remained black.

Apart from the modifications producible by Position, the Rhythm of Measured Music was regulated by the three-fold mechanism of Mode, Time, and Prolation; three distinct systems, each of which might be used, either alone, or in combination with one or both of the others; each being distinguished by its own special Time-Signature. [See Mode, Time, Prolation, Time-Signature.]

Mode governed the proportion between the Large and the Long, and the Long and the Breve; and was of two kinds—the Greater, and the Lesser; each of which might be either Perfect or Imperfect. In the Greater Mode Perfect, the Large was equal to three Longs; in the Greater Mode Imperfect, it was equal to two only. In the Lesser Mode Perfect, the Long was equal to two Breves; in the Lesser Mode Imperfect, it was equal to two. The Modal Signs by which these varieties were indicated differed considerably at different periods; but the following were the forms most frequently employed:—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Great Mode Perfect. Great Mode Imperfect.

Lesser Mode Perfect. Lesser Mode Imperfect.

Time regulated the proportion between the Breve and the Semibreve; and was of two kinds, Perfect and Imperfect. In Perfect Time, the Breve was equal to three Semibreves; in Imperfect Time, to two only. The following example shews the Time - Signatures most frequently used:—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Perfect Time; or, thus; or, thus.

Imperfect Time; or, thus; or, thus.

Prolation concerned the proportion between the Semibreve and the Minim; and was also of two kinds, the Greater and the Lesser—or, as Morley calls them, 'the More and the Lesse.' In the Greater Prolation, the Semibreve was equal to three Minims; in the Lesser, to two.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

The Greater Prolation; or, thus; or, thus.

The Lesser Prolation; or, thus; or, thus.

The general principle observed in the formation of these Time-Signatures is, that the Rests shew the proportion between the Large, the Long, and the Breve; the Circle, the figure 3, and the Point, are signs of Perfection; the Semicircle, and the figure 2, denote Imperfection; while the Bar drawn through the Circle, or Semicircle, indicates Diminution of the value of the notes, to the extent of one-half, as does also the inversion of the figures, thus (Music characters). In a few rare cases, a double Diminution, to the extent of one fourth, was denoted by a double Bar drawn through the Circle, or Semicircle, thus (Music characters). These rules, however, though applicable to most cases, were open to so many exceptions, that Ornithoparcus, writing in 1517, and Morley, in 1597, roundly abuse their uncertainty. In very early times, the three rhythmic systems were combined in proportions far more complex than any of the Compound Common or Triple Times of modern Music. In Canons, and other learned Compositions, two or more Time-Signatures were frequently placed at the beginning of the same Stave. In a portion of the Credo of Hobrecht's Missa 'Je ne demande' we find as many as five:—

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

These complications were much affected by Josquin des Prés, and the early Composers of the Flemish School; but, in the latter half of the 16th century—the so-called 'Golden Age'—the only combinations remaining in general use were, Perfect Time, with the Lesser Prolation ((Music characters) 3, or (Music characters)); Imperfect Time, with the Lesser Prolation ((Music characters)); the Greater Prolation alone ((Music characters)); and the Lesser Prolation ((Music characters)) answering, respectively, to the (Music characters), Alla Breve, (Music characters), and Common Time, of our present system. [See Proportion.]

The Perfection and Imperfection of the longer notes, and the duration of the shorter ones, was also materially affected by the addition of Points, of which several different kinds were, in use, all similar in form ((Music characters)), but differing in effect, according to the position in which they were placed.

The Point of Augmentation was the exact equivalent of the modern Dot—that is to say, it increased the length of the note to which it was attached, by one half. It could only be used with notes naturally Imperfect; and was necessarily followed by a shorter note, to complete the beat.

Sometimes, the place of this sign was supplied by two black notes; the first of which, losing one fourth of its value by virtue of its colour, represented the note with the Point, while a shorter black note completed the beat. Passages are constantly written in both ways, in the same compositions.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written; or thus. Sung.

Written; or thus; more rarely. Sung.

The Point of Perfection was used for two different purposes. When placed in the centre of a Circle, or Semicircle, it indicated either Perfect Time, or the Greater Prolation. When placed after a note, Perfect by virtue of the Time-Signature, but made Imperfect by Position (see page 471), it restored its Perfection. In this case, the Point itself served to complete the triple beat; in which particular alone it differed from the Point of Augmentation. Thus, the second Semibreve in the following example, being succeeded by a Minim, would become Imperfect by Position, were it not followed by a Point of Perfection. The third Semibreve, being preceded by a Minim, really does become Imperfect; while the first and last Semibreves remain Perfect, by virtue of the Time-Signature.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written. Sung.

The Point of Alteration, or, as it was sometimes called, the Point of Duplication, was less simple in its action. When used, in Ternary Rhythm, before the first of two short notes placed between two long ones, it doubled the length of the second short note, and restored the Perfection of the two long ones, which would otherwise have become Imperfect by Position. In order to distinguish this sign from the Point of Augmentation, the best typographers usually placed it above the general level of the notes to which it belonged—a precaution the neglect of which causes much trouble to modern readers.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written. Sung.

Sometimes the old writers, dispensing with the actual Point, used, in its stead, two black notes, which, it will be remembered, lost, in Perfect Time, one third of their value. Thus the second clause of the following example precisely corresponds with the first; since the black Breve, being, by virtue of its colour, equal to two Semibreves only, serves exactly to complete the measure begun by the black Semibreve (which, in this case, retains its full value). Examples, both of the Point and the black notes, will be found, not only in works of the 15th century, but even in those of Palestrina, and most of his contemporaries.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written; or thus. Sung.

The Point of Division, sometimes called the Point of Imperfection, exercised a contrary effect. When two Semibreves were placed between two Breves, in Perfect Time, or two Minims between two Semibreves, in the Greater Prolation, a Point of Division inserted between the two shorter notes generally on a higher level served to shew that the two longer ones were to be considered Imperfect.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written. Sung.

As these notes were already Imperfect, by Position, the Point made no real difference, but was merely added for the sake of preventing all possibility of misconception. Joannes Tinctoris, writing in the 15th century, expressed his contempt for such unnecessary signs by calling them Ass's Points (Puncti asinei). Nevertheless, they were constantly used by Palestrina and his contemporaries; who, however, sometimes dispensed with the Point, and wrote the two last notes of the passage black, with the understanding, that, in this case, they were to retain their full value. The effect of this arrangement was, that the several clauses of the following example were all sung exactly in the same way.

A musical score should appear at this position in the text. See Help:Sheet music for formatting instructions |

Written; or thus; or thus. Sung.

While the Virga, and Punctus, of the earlier system were thus developed into the detached notes of Measured Music, the more complicated Neumæ gradually shaped themselves into Ligatures—that is to say, passages of two or more notes, sung to a single syllable. As the most important of these have already been described, in a former article [see Ligature], we shall content ourselves with rapid sketch of the changes through which they passed, at different periods of their history. In Plain Chaunt, they were always black, and more or less angular in form, whereas the older Neumæ were, for the most part, rounded. In Measured Music, they were white; and formed of square or diagonal (not lozenge-shaped) figures, placed in close contact with each other, and sometimes provided with Tails, the varied position of which regulated their classification into Larges, Longs, Breves, and Semibreves; notes shorter than the Semibreve not being 'ligable.' In the 15th century, the number of notes contained in a single group was often very considerable; and their duration was governed by many complicated laws, of which the following were the most strictly enforced, especially by the earlier Composers of the Flemish School.

The first note of every Ligature was a Long, provided it had no Tail, and the second note descended—a Breve, if it had no Tail, and the second note ascended. In the first of these cases, it was called a Ligatura cum proprietate; in the second, a Ligatura sine proprietate.

If the first note had a Tail, descending, on the left side, it was a Breve, and sine proprietate. If it had a Tail ascending, on the left side, it was a Semibreve, and the Ligature was said to be cum opposita proprietate.

If the last note descended, it was a Long; if it ascended, a Breve. In the first case, the Ligature was said to be Perfect, in the second, Imperfect. But, when placed obliquely, whether ascending or descending, it was a Breve, unless it had a Tail descending on the right side, in which case it was a Long.

All intermediate notes were, as a general rule, Breves: but, if one of them had a Tail, ascending on the left side, it was a Semibreve.

Lastly, a Large, in whatever part of the Ligature it might be placed, was always a Large.

In the 16th century,, these laws were very much simplified. The Ligatures used in the time of Palestrina seldom contained more than two notes; or, if more were included in the figure, they were treated as if not in Ligature. The following easy rules will serve for most Music of later date than the year 1550.

Square notes, in Ligature, without Tails, were almost always Breves: but, if the second note descended, they were sometimes Longs; or, the first might be a Long, and the second a Breve.

Square notes, in Ligature, with a Tail descending on the right, were Longs; those with a Tail descending on the left, Breves; those with a Tail ascending on the left, Semibreves.

Black notes were sometimes combined with white ones; and, occasionally, figures were made half white, and half black. In these cases, each colour was subject to its own peculiar laws.

Points attached to a Ligature affected it as they would have affected ordinary notes.

In the 15th century, the F, C, and G Clefs were used on a great variety of Lines. Before the invention of Ledger Lines, their position was frequently changed, even in the middle of a Melody, in order to bring the extreme notes of the Scale within the compass of the Stave. This being the case, it was impossible to assign a distinctive Clef to each particular quality of Voice, as we do. The Clefs were, therefore, divided into the four general classes of Cantus, Altus, Tenor, and Bassus; and varied, in position, according to circumstances. When more than four Voices were used, the fifth part was called Quintus, or Quinta pars; the sixth, Sextus, or Sexta pars; and so with the rest: but, as care was taken that each additional Voice should exactly correspond in compass with one of the normal four, we scarcely ever find more than four Clefs used in the same Composition. The ten forms most frequently employed in the infancy of Polyphonic Music are shewn in the following example, with the old classification indicated above the Stave, and the modern names, below it.

The Polyphonic Composers of the best periods were extremely methodical in their choice of Clefs, which they so arranged as to indicate, within certain limits, whether the Modes in which they wrote were used at their natural pitch, or transposed. [See Modes, the Ecclesiastical]. The Natural Clefs—Chiavi naturali—were the well-known Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass, which have remained in common use, among Classical Composers, to the present day. The transposed Clefs—Chiavi trasportati, or Chiavette were of two kinds, the Acute, and the Grave. The former were the Treble (Violino), Mezzo Soprano, Alto, and Tenor,—or Barytone. The latter consisted of the Alto, Tenor, Barytone, and Bass or Contra-Basso. The effect of this method of grouping was, that, when the Mode was written, at its true pitch, in the Chiavi naturali, the Chiavette served to transpose it a Fourth higher, or a Fifth lower: if, however, it was written at its natural pitch, in the Chiavette, it was transposed by aid of the Chiavi naturali. The High Treble and Contra-Tenore were very rarely used, after about the middle of the 16th century; and the Contra-Basso did not long survive them; but the remaining seven forms were so constantly employed, that a familiar acquaintance with them is indispensable to all students of Polyphonic Music.

The Flat and the Natural were known and used at a very early period—certainly long before the time of Guido—the former, under the name of the B rotundum, or B molle (b), and the latter, under that of B quadrum, or B durum ((Music characters)). [See B, vol. i. 107.] The Sharp, or Diesis, has not been traced back farther than the latter half of the 13th cent., when we find it, in some French MSS. in the form of a double S. Andrew's cross (⨳)—as in Adam de la Bale's Rondellus 'Fines amourettes.' In the 14th century, Ottobi classes it with the B rotundum, and B quadrum, and calls it B giacente ((Music characters)). In the 15th and 16th centuries it quite displaced the Natural; and was used, in its stead, to correct a B which would otherwise have been sung Flat. A single B♭ was always placed at the Signature, in the transposed Modes. The use of two Flats, indicating a double transposition—as in P. de la Rue's 'Pour quoi non,' preserved in Petrucci's Odhecaton—is excessively rare. Still more so is a Sharp Signature: though examples may be found in Zarlino; and in Okeghem's 'Prennez sur moy,' printed in Petrucci's 'Canti cento cinquanta.'

In Hobrecht's 'Forseulement,' and Barbyrau's Missa 'Virgo parens Christi,' an F♭ is placed at the Signature, as a sign that the Mode is Mixolydian, at its natural pitch, and that its Seventh Degree is not to be sharpened. These cases, however, are altogether abnormal, and must not be taken as precedents. Both the spirit and the letter of Mediæval Music forbade the introduction of anything, at the Signature, beyond the orthodox B rotundum.

Accidental Sharps, Flats, and Naturals, very rarely appeared in writing; the Singer being expected to introduce the necessary Semitones, in their proper places, at the moment of performance, in obedience to certain laws, with an epitome of which the reader has already been furnished. [See Musica Ficta.] This practice remained in full force, until the close of the 16th century; and is even now observed in the Pontifical Chapel.

Indications of Tempo, Dynamic Signs, and Marks of Expression of all kinds, were altogether unknown to the Composers of the 15th and 16th centuries, unless, indeed, we are prepared to recognise their prototypes in the singular Mottos, and Ænigmas, prefixed to the Canons, which, in the time of Ockeghem, and Josquin des Prés, were so zealously cultivated by Composers of the Flemish School. [See Inscription.]

A few arbitrary signs, however, were in constant use.

When Canons were written on a single Stave, the Presa ((Music characters)) shewed the place at which the second, third, or other following Voice was to begin.

The Pause (![]() ) indicated the note on which such Voices were to close. But it was also placed, as in modern Music, over a note which the Singer was expected to prolong indefinitely—as in Basiron's 'Messa de franza' (printed in 1508), wherein, at the words 'Et homo factus est,' Pauses are placed over no less than eight Breves in succession.

) indicated the note on which such Voices were to close. But it was also placed, as in modern Music, over a note which the Singer was expected to prolong indefinitely—as in Basiron's 'Messa de franza' (printed in 1508), wherein, at the words 'Et homo factus est,' Pauses are placed over no less than eight Breves in succession.

The sign of repetition was a thick bar, with dots on either side, like our own. When the bar was double, the passage was sung twice; when it was triple, thrice. A passage in Hobrecht's Missa 'Je ne demande' is directed to be sung five times ((Music characters)). When words were to be repeated, a smaller sign was used ((Music characters)), and reiterated at each repetition of the text.

Ottaviano dei Petrucci—who first printed Music from moveable types, in the year 1501—Antonio Gardano, Riccardo Amadino, Christoph Plantinus, Peter Phalesius, Pierre Attaignant, Robert Ballard, Adrian le Roy, our own John Daye, and Vautrollier, and other early typographers, each gloried in a certain individuality of style which the Antiquary never fails to recognise at a glance. But, the general character of musical typography underwent no radical change, from the first invention of printing, until the close of the 16th century. In this respect Plain Chaunt was even more conservative than Measured Music. After the invention of the Square Notes—Notulæ quadratæ, the Gros fa of French Musicians—it was always printed, as now, in black Longs, Breves, and Semibreves, on a Stave of Four Lines, on either of which the F or C Clef might be placed, indiscriminately. The G Clef was never used. Time-Signatures, Rests, Points, and other signs used in Measured Music, were, of course, quite foreign to its nature: but, black Ligatures, angular in character, and of infinitely varied form, were of constant occurrence. As no change in the constitution of Plain Chaunt is possible, no change in its Notation is either needed or desired. But, with Rhythmic Music, the case is very different; and we can readily understand that the Notation of the 16th century proved insufficient, in many ways, to meet the necessities of the 17th.

The daily-increasing attention bestowed upon Instrumental Accompaniment, during the development of the Monodic Style, led to some very important changes. [See Monodia.] The varying compass of the Instruments employed demanded a corresponding extension of the Stave, which was provided for by the unlimited use of Ledger Lines. A single Ledger Line, above or below the Stave, may, indeed, be occasionally found among the Polyphonic Music of the 16th century; but, only in very rare cases. The number of additional lines was now left entirely to the Composer's discretion; and it has continued steadily to increase, to the present day.

Polyphonic Music was always printed in separate parts. Sometimes, as in the case of Ottavio del Petrucci's rare volumes, each part appeared, by itself, in a delicious little oblong 4to. Sometimes, as in the Roman editions of Palestrina's Masses, four or more parts were exhibited, at a single view, on the outspread pages of a large folio volume. But, the connection between the parts was never indicated; and the Music was never barred—a peculiarity, which, in this case, seems to have produced no inconvenience. This plan, however, was quite unsuited to the new style of composition. When Peri published his 'Euridice,' in the year 1600, he placed the Instrumental Accompaniment below the Vocal part, and indicated the connection between the two by means of Bars, scored through the Stave—whence the origin of our English word Score. The same plan was followed by Caccini, in his 'Nuove Musiche,' in 1602; and, by Monteverde, in 'Orfeo,' in 1608: and the practice of printing in Partition, as score has always been called every where but in England, soon became universal.

The new Bars were a great help to the reader; but, the invention of the Cantata, the Opera, and the Oratorio, introduced new forms of Rhythm which it was all but impossible to express with clearness, even with their assistance, so long as the cumbrous machinery of Mode, Time, and Prolation, remained in common use. To meet this difficulty, the Time-Table itself was entirely remodelled—not in essence, for the broad distinction between Binary and Ternary Rhythm formed the basis of the new, as well as of the old system but, in the means by which that fundamental principle was enunciated, and its results expressed in writing. The great advantage of the new method lay in the recognition of a definite value for every note employed. The longer notes were no longer made Perfect, or Imperfect, by Position; but all were referred to the Semibreve, as a fixed standard of duration; and all, without exception, were subject, in their natural forms, to binary division, and could only be made ternary by the addition of a dot—the old Point of Augmentation—which increased their value by one half. The chief factors of the system were, the aliquot parts of the Semibreve, as represented by the Minim, the Crotchet, the Quaver, and the Semiquaver. A certain number of these factors, now called the Beats of the Bar, was allotted to each Measure of the Music. When that number was divisible by 2, the Time was said to be Common; when it was divisible only by 3, the Time was Triple. To express the more complicated forms of Rhythm, the several Beats were themselves subjected to a farther process of subdivision, which might be either binary, or ternary, at will. When it was binary, the Time, whether Common, or Triple, was said to be Simple. When it was ternary, in which case each Beat represented a dotted note, the Time was called Compound; and with very good reason; each Measure being, in reality, compounded of two or more shorter Measures of Simple Triple Time.

The Time-Signatures by which this new system was expressed in writing were, for the most part, fractions; the denominators of which indicated the proportion between the Beats of the Bar and the typical Semibreve, while the numerators denoted the number of such beats to be taken in a Measure. When the numerator was divisible only by 2, it indicated Simple Common Time; when only by 3, Simple Triple. In Compound Common Time it was divisible either by 2, or 3; and, in Compound Triple, by 3, and 3 again. The only exceptions to this practice were formed by the retention of the Semicircle, for Common Time with four Crotchets in a Measure, and the barred Semicircle, for the Time called Alla Breve, with four Minims.[11] The Simple Common Times most used in the 17th and 18th centuries were, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and 24; the Simple Triple Times, 31, 32, 34, and 38; the Compound Common Times were 62, 64, 68, 616, 124, 128, 1216, and 2416; and the Compound Triple Times, 92, 94, 98, and 916. Mozart, as if in emulation of the departed mysteries of Proportion, has used 34, 24, and 38, simultaneously, and with wonderful effect, in the well-known Minuet in 'Don Giovanni'; and Spohr has used similar combinations in the Slow Movement of his Symphony, 'Die Weihe der Töne.' The last-named Composer has also used 88, in the Overture to his finest Opera, [12]Faust; and 28, in the Second Act of the same work.

, and 24; the Simple Triple Times, 31, 32, 34, and 38; the Compound Common Times were 62, 64, 68, 616, 124, 128, 1216, and 2416; and the Compound Triple Times, 92, 94, 98, and 916. Mozart, as if in emulation of the departed mysteries of Proportion, has used 34, 24, and 38, simultaneously, and with wonderful effect, in the well-known Minuet in 'Don Giovanni'; and Spohr has used similar combinations in the Slow Movement of his Symphony, 'Die Weihe der Töne.' The last-named Composer has also used 88, in the Overture to his finest Opera, [12]Faust; and 28, in the Second Act of the same work.

It must not be supposed that this admirable system sprang into existence in a moment of time. It was the result of long experience, and many tentative experiments; but we have preferred to treat of it, in its perfect condition, rather than to dwell upon the successive stages of its progress; and the more so, because, since the time of Bach, and Handel, it has undergone scarcely any change whatever.[13] Those who care to study its transitional forms will find some curious examples among the numerous Ricercari, Toccate, and Capricci, composed for the Organ by Frescobaldi, during the earlier half of the 17th century.

When the old Ecclesiastical Modes were abandoned in favour of the modern Major and Minor Scales, the insertion of accidental Sharps, Flats, and Naturals, was no longer left to the discretion of the performer. The place of every Semitone was indicated, exactly, in writing; and, in process of time, the Double-Sharp (×) and Double-Flat (♭♭) corrected by the ♮♯ and ♮♭, were added to the already existing signs. A curious relique of the mediæval custom was, however, retained in general use, until nearly the end of the 18th century, when the last Sharp or Flat was suppressed, at the Signature, and accidentally introduced, during the course of the piece, as often as it was needed. Thus, Handel's Fifth Lesson for the Harpsichord (containing the 'Harmonious Blacksmith') was originally written with three Sharps only at the Signature, the D being everywhere made sharp by an accidental. (See the editions of Walsh and of Arnold.) A few of these 'Antient Signatures'—as they are now called—may still be seen, in modern reprints; as in Mills's edition of Clari's Duet, 'Cantando un di,' which, though written in A major, has only two Sharps at the Signature.

The rapid passages peculiar to modern Instrumental Music, and not unfrequently emulated by modern Vocalists, naturally led to the adoption of characters more cursive in style than the quaint old square and lozenge-headed notes, and capable of being written with greater facility. Thus arose the round, or rather oval-headed notes, which, in the 18th century, completely supplanted the older forms. Lozenge-headed Quavers, and Semiquavers, whatever their number, were always printed with separate Hooks. The Hooks of the round-headed ones were blended together, so as to form continuous groups, containing any number of notes that might be necessary—a plan which greatly facilitated the work both of the writer, and the reader. Moreover, with the increase of executive powers, arose the demand for notes indicating increased degrees of rapidity; the Semiquaver was, accordingly, subdivided into Demisemiquavers, with three Hooks, and Half-Demisemiquavers, with four—the number of additional Hooks being, in fact, left entirely to the discretion of the Composer.[14]

The introduction of the dramatic element played a most important part in the development of modern Music; and, in order to do it justice, it became imperatively necessary to indicate, as precisely as might be, the particular style in which certain passages were to be performed. As early as 1608, we find, in the Overture to Monteverde's 'Orfeo,' a direction to the effect that the Trumpets are to be played con sordini. It was manifestly impossible to dispense, much longer, with indications of Tempo. Frescobaldi was one of the first great writers who employed them; and—strangely enough, considering his birth in Ferrara, and long residence in Rome—one of his favourite words was Adagio, spelled, as in the Venetian dialect, Adasio. The idea once started, the words Allegro, Largo, Grave, and others of like import, were soon brought into general use; and their number has gradually increased, until, at the present day, it has become practically infinite. As a general rule, Composers of all nations have, by common consent, written their directions in Italian; and, as a natural consequence of this practice, many Italian words have been invested with a conventional signification, which it would now be difficult to alter. Beethoven, however, at one period of his life, substituted German words for the more usual terms, and we find, in the Mass in D, and some of the later Sonatas, such expressions as Mit Andacht, Nicht zu geschwind, and many others. [See Beethoven, vol. i. p. 193b.] He soon relinquished this novel practice; but Mendelssohn sometimes adopted it—as in Op. 62, No. 4, marked Mit vieler Innigkeit vorzutragen, and numerous other instances. Schumann, also, wrote almost all his directions in German: and the custom has been much affected by German Composers of the present day. A few French Musicians have fallen into the same habit;[15] and it was not unusual, at the close of the last and beginning of the present century, to find English Composers—especially in their Glees—substituting such words as 'Chearful,' and 'Slower,' for Allegro, and Più Lento. Nevertheless, the Italian terms still hold their ground; and the adoption of a common language, in such cases, is too obvious an advantage to be lightly sacrificed to national vanity.

We have already noticed the first indications of Dynamic Signs, in the Antiphonary of S. Gall. This, however, was quite an exceptional case. Such marks were utterly unknown to the Polyphonists of the 15th and 16th centuries; and it was not until the 17th was well advanced, that they met with general acceptance. In the 18th century, however, all the more essential signs, such as f, p, fp, fz, cres., dim., and their well-known congeners, were in full use; and the numerous forms now commonly employed are really no more than elaborate synonyms for these. Marks of expression, properly so called, such as (Music characters), and a host of others, though not unknown in the last century, were much less frequently used than now. The Slur, however, the modern substitute for the Mediaeval Ligature, and an infinite improvement upon it, was constantly employed, both to shew how many notes were to be sung to a [16]single syllable, and to indicate the Legato style. So, also, were the marks for Staccato (•) Staccatissimo ('), and Mezzo Staccato ((Music characters)). But the opposite to these (–) is of very recent invention indeed; and has only, within a very few years, taken the place of the far less convenient term ten. (dim. of tenuto). The Tie, or Bind ((Music characters)), is found in the Score of Peri's 'Euridice,' printed in 1600. The Swell ((Music characters)) was first used by Domenico Mazzocchi, in a collection of Madrigals, printed in 1638. The Pause has undergone no change whatever, either in form, or signification, since the time of Basiron. As in the days of Obrecht, the Dotted Double Bar is still used as the sign of repetition; though a tripled bar would no longer be understood to indicate that the passage was to be sung or played thrice; and the dots are not now placed on both sides of the bar, unless the passages on both sides are intended to be repeated. The convenient forms of 1ma and 2nda volta date from the last century. We first find the term Da Capo—now better known by its diminutive, D.C.—in Alessandro Scarlatti's Opera, 'Theodora,' produced in 1693 [App. p.732 "Cavalli's 'Giasone,' 1655"]. For this, when the performer is intended to go back to the Presa ((Music characters)) the words Dal Segno are more correctly substituted, with the word Fine, to indicate the final close.

The innumerable Graces which formed so conspicuous a feature in the Music of the last century, and the greater number of which are now entirely obsolete, had each their special sign. By far the most important of these was the true Appoggiatura, which, though always written as a small note, took half the value of the note it preceded, unless that note was dotted, in which case it took two thirds of it; while the Acciaccatura, though exactly similar in form, was always played short. The Appoggiatura is now always written as a large note, and the Acciaccatura as a small one: but, it is impossible to play the works of Haydn, or Mozart, correctly, without thoroughly understanding the difference between the two. [See Appoggiatura; Acciaccatura.] The variety of Shakes, Turns, Mordents, Cadents, Backfalls, and other Agrémens, cultivated by performers who have scarcely, even yet, passed out of memory, was very great. A valuable explanation of some of those used in the last century, is given in Griepenkerl's edition of the Organ Works of J. S. Bach, on the authority of a letter written by that Master himself, and, happily, still in existence. [See Agrémens, Mordent, Shake, Turn, etc., etc.]

Of the numerous Clefs employed in the 16th century, five only have been retained. In Full Scores, Classical Composers still write their Voice Parts in the time-honoured Chiavi naturali Soprano, Alto, Tenor, and Bass. In the so-called P.F. Scores of the present day, the Treble Clef is always substituted for the Soprano; and, very often, for the Alto and Tenor also, with the understanding that the Tenor is to be sung an Octave lower than it is written. [App. p.732 "the tenor part in choral works is sometimes indicated by two G clefs close together. Messrs. Ricordi & Co. use a somewhat barbarous combination of the G and C clefs for the same purpose."] When this method was first invented, the Alto was also written in the Octave above that in which it was intended to be sung—as in Dr. Clarke's edition of Handel's Works: but this most inconvenient plan is now happily abandoned; and the Alto part is always written at its true pitch, even when transposed into the Treble Clef. Solo Voice-parts are also written, in full Scores, in their proper Clefs. In P.F. Scores, all except the Bass are always written in the Treble Clef. Handel sometimes used the Treble Clef, so far as the Songs were concerned, even in his Full Scores; and hence it is that, in many cases, we only know by tradition whether a certain Song is intended to be sung by a Soprano or a Tenor. Of course this observation does not apply to the great Composer's Choruses, which were always written in their proper Clefs.

Every Orchestral or other Instrument has, also, its proper Clef; and, in many cases, a distinctive Method of Notation. Violin Music is always written in the Treble Clef—to which, indeed, the name of the Violin Clef is given, everywhere but in England; and to save Ledger Lines, the high notes are sometimes written in the octave below, with the diminutive 8va, and the dotted line, above them.

The Viola always plays from the Alto Clef.

The Violoncello has a peculiar Notation of its own. Its normal Clef is the Bass; but the higher notes are generally written in the Tenor—sometimes, though less frequently, in the Alto. The highest notes of all are written in the Treble Clef; but, with the understanding that they are to be played an Octave lower than they are written, unless the word loco is placed over them, in which case they are to be played in their true place. When 8va … is placed over them, they are played an Octave higher than they are written. Beethoven, in his P.F. Trio in B♭, Op. 97, gives full directions to this effect; but some writers for the Violoncello, dispensing with the word loco, place 8va … over the notes which they wish to be played at their true pitch.

The Contra-Basso part is always written in the Bass Clef; but the Instrument sounds the note an octave lower than it is written. In the Orchestra, the player sits at the same desk as the Violoncello, and plays from the same part: but it is understood that he is to be silent, when any other than the Bass Clef is used, or, when the part is marked 'cello'; and not to play again, until the Bass Clef is resumed, or the part marked Basso. Since the time of Beethoven, a separate part has often been written for the Contra-Basso; but the player always looks over the same book as the Violoncello.

Flutes and Oboes always play from the Treble Clef. Clarinets also play from the Treble Clef; but parts for the B♭ Clarinet are written a Major Second, and those for the A Clarinet a Minor Third, higher than they are intended to sound. Thus, in Beethoven's Symphony in C minor, the B♭ Clarinet parts are written in D minor; and in Mozart's Overture to Figaro (in D), the A Clarinet parts are written in F; while, in both cases, the Instrument transposes the notes to the required pitch, without farther interference on the part of the player. The Corno di Bassetto, or Tenor Clarinet, plays every note a Fifth lower than it is written; its part, therefore, when intended to be played in the key of F, must be written in that of C: and the same peculiarity characterises the Cor Anglais, or Tenor Oboe.

The normal Clef for the Bassoon is the Bass; but the Tenor Clef is frequently employed, for the highest notes, to save Ledger Lines. The Double Bassoon also uses the Bass Clef, sounding every note an Octave lower than it is written.

Trumpet parts are written in the Treble Clef, and always in the key of C; the Instrument being made to transpose them to the required pitch by the addition, or removal, of Crooks. In the time of Handel, Trumpets rarely played in any other keys than those of C and D; and the parts were then always written in the key in which they were intended to be played. Horn parts are written exactly in the same way as Trumpet parts; and the Instrument transposes them, in like manner, but in the Octave below. The few lower notes for the Horn are, however, frequently written in the Bass Clef. The Alto, Tenor, and Bass Trombones, play from the Alto, Tenor, and Bass Clefs, respectively.

The Drums, as a general rule, play only two notes—the Tonic, and Dominant: and these are usually [App. p.732 "were formerly"] written in C, and transposed by the manner of tuning the Instrument. Sometimes [App. p.732 "In modern music"], however, the true notes are written; especially when more than two Drums are used.

The Wind Instruments used in Military Bands stand in a great variety of keys, thereby causing much complication in the Notation of the Score.

In the Scores of Handel, Haydn, and Mozart, the Organ is usually made to play from the ordinary Bass part, which is figured throughout, and thus converted into a 'Thorough-base,' in order to indicate the chords with which the Organist is expected to enrich the composition. When the letters T.S.—for Tasto solo—are substituted for the figures, the Organist omits the Chords, and plays the Bass only, in unison, until the figures reappear. The Organ part is only written in full, on two Staves, when it is purely obbligato—as in Handel's 'Saul.' In old Organ and Harpsichord Music—both written in precisely the same way—frequent use is made of the Tenor Clef; but it has never been used for the Pianoforte, the Notation for which is chietty remarkable for the number of its Ledger Lines, notwithstanding the constant use of the diminutive 8va. placed over notes written in the octave below. When the Pedal was first brought into general use, it was indicated by the sign *, or the words senza sordino; the sign ⊕, or the words con sordino, shewing the place at which it was to be removed. It is now indicated by the abbreviation Ped.; and its removal, by an asterisk *, or, as in some of Beethoven's later works, a little cross +. The words una corda, or the letters U.C., indicate the 'Soft Pedal'; and the words tre corde, or the letters T.C., are used to direct its removal. In Beethoven's Sonata, Op. 106, the gradual removal of the 'Soft Pedal' is indicated thus:—Una corda. Poco a poco due ed allora tutte le corde. In the days when he affected German terms, he used the words mit Verschiebung. [See Verschiebung.]

In old Pianoforte Music, Abbreviations are of frequent occurrence. They are now very rarely used; and are, indeed, commonly supposed to indicate a very debased style of typography: nevertheless, they frequently serve to facilitate the process of reading very considerably. In Orchestral Parts, they are still extensively used; especially in tremolos, and other similar passages, in which, while economising space, they save readers an immensity of trouble. [See Abbreviations, Horn, Trumpet, Bassoon, Double Bassoon, Clarinet, etc., etc.]

If perfect adaptation of the means used to the end proposed be accepted as a fair standard of excellence, our present system of Notation leaves little to be desired; for it is difficult to conceive any combination of sounds, consistent with what we believe to be the true principles of Musical Science, which it is incapable of expressing. Attempts have been made, over and over again, to supersede it by newer inventions: but, with the exception of the 'Tonic Sol-fa' [17]system, and its French equivalent, the Méthode Galin-Paris-Chevé, not one of them has succeeded in commanding serious attention. It is impossible that we can set aside arrangements, the convenience of which has been tested by so many centuries of experience, in favour of such Methods as that advocated by the 'Chroma- Verein des gleichstüfigen Tonsystems,' the 'Keyboard Method of Notation, or Chromatic Stave,' or any other systems, good or bad, of modern invention, whether based upon the results of private experience, or scientific calculation, whatever may be the amount of ingenuity displayed in their construction. Like the Chiffres proposed by Louis Bourgeois, in the 16th century, they may, for a time, attain a certain amount of delusive popularity; but, sooner or later, they must, and invariably do, fall to the ground. And the reason is obvious. Our recognised system is an universal Language, common to all civilised countries; whereas, the empirical methods which have been proposed as substitutes for it are, like the Tablature for the Lute, fitted, at their best, only to answer some special purpose, often of very slight importance. The 'Tonic Sol-fa' system, for instance,—even setting aside the grave faults which it shares with the older Alphabetical Method long since condemned—could never be used for any other purpose than that of very commonplace Part Singing, while the time spent in acquiring it could scarcely fail, if devoted to the study of ordinary Notation, to lead to far higher results. (See Tonic Sol-Fa; Key, II, vol. ii. p. 55 a; Bourgeois, Louis, Appendix.] We may, therefore, safely predict, for the present Written Language of Music, a future co-ordinate with that of the Scientific Principles of which it has so long been the recognised exponent.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ The authenticity of the three Hymns, printed, in 1581, by Vincenzo Galilei, rests on such slender grounds, that it would be extremely unsafe to accept them as genuine.

- ↑ The septem discrimina vocum of Virgil (Æn. vi. 645) have been supposed to allude to these seven letters; and the context certainly suggests some possible connection with the subject.

- ↑ Though discussion of individual authorities is quite foreign to the purpose of the present article, it may be well to observe, that, within the last five years, a well-known Belgian writer—F. A. Gevaert—has advanced certain opinions connected with the subject of antient Notation, very much at variance with those of most earlier Historians. The reader will find Mons. Gevaert's views fully explained in his 'Histoire et Theorie de la Musique dans l'Antiquité,' Paris, 1876.

- ↑ From , a nod, or sign; or, as some have supposed, from , the long succession of notes sung after a Plain Chaunt 'Alleluia.'

- ↑ Printed, at Brussels, in fac-simile, by P. Lambillotte, in 1861. The first page is also given in the 2nd vol. of Pertz's 'Monumenta Germaniae historica.' All authorities agree in regarding the MS. as one of the most interesting reliques of early Notation we possess; but it is only right to say that its date has been hotly disputed, and that doubt has even been thrown upon the identity of its forms with those used in the older Antiphonarium.

- ↑ It is impossible to give the exact date. The antiquity of MSS. can very rarely be proved beyond the possibility of cavil.

- ↑ Hence, frequently called 'Monachus Elnonensis.' Ob. 930.

- ↑ Bodley MSS. 775.

- ↑ From a MS. of the 14th century, preserved In the Library of the University at Prague, (xiv. G. 46.) In the original Codex, an extra line has been added (ungeschickter Weise gezogen, Ambros say) between the Third and Fourth, to mark the place of the F Clef. In order to preserve the clearness of the example, we have here omitted it.

- ↑ 'Quod a summa Trinitate, quæ vera est et summa perfectio, nomen assumsit.' (Franco, 'Musica et cantus mensurabilis,' cap. iv.)

- ↑ A quick form of Simple Common Time, with two Minim Beats In the Measure, is used, in modern Music, with the Signature of the barred Semicircle, and very improperly called Alla Breve. Mendelssohn much regretted that he did not bar the Semicircle in his Overture to Die Meerestille.

- ↑ In the P.F. arrangement, only: not in the Full Score.

- ↑ Unless we except the praxis of the Modern Italian Composers, who always write In Simple Time, and make it Compound by the insertion of Triplets—a strange contrast to the conscientious 2416 of the 'Harmonious Blacksmith.'

- ↑ The slowness with which these innovations were accepted is well exemplified in an article in the 'Penny Cyclopaedia,' (1833–5) the writer of which, lamenting the addition of unnecessary Hooks, regrets that he is obliged to mention the name of Beethoven among those who have been guilty of this monstrous absurdity!

- ↑ Berlioz, for instance, indicates the use of 'Harpes, deux au moins,' and 'Baguettes d'eponge'!

- ↑ See Mendelssohn's protest against this in Letter to Macfarren. 'Goethe and Mendelssohn.' 2nd ed. p. 177.

- ↑ For an account of the 'Moveable Do,' which forms the chief characteristic of this system, see Solmisation.