A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Overture

OVERTURE (Fr. Ouverture; Ital. Overtura), i.e. Opening. This term was originally applied to the instrumental prelude to an opera, its first important development being due to Lulli, as exemplified in his series of French operas and ballets, dating from 1672 to 1686. The earlier Italian operas were generally preceded by a brief and meagre introduction for instruments, usually called Sinfonia, sometimes Toccata, the former term having afterwards become identified with the grandest of all forms of orchestral music, the latter having been always more properly (as it soon became solely) applied to pieces for keyed instruments. Monteverde's opera, 'Orfeo' (1608) commences with a short prelude of nine bars, termed 'Toccato,' to be played three times through—being, in fact, little more than a mere preliminary flourish of instruments.[1] Such small beginnings became afterwards somewhat amplified, both by Italian and French composers; but only very slight indications of the Overture, as a composition properly so called, are apparent before the time of Lulli, who justly ranks as an inventor in this respect. He fixed the form of the dramatic prelude; the overtures to his operas having not only served as models to composers for nearly a century, but having also been themselves extensively used in Italy and Germany as preludes to operas by other masters. Not only did our own Purcell follow this influence; Handel also adopted the form and closely adhered to the model furnished by Lulli, and by his transcendent genius gave the utmost development and musical interest attainable in an imitation of what was so entirely conventional. The form of the Overture of Lulli's time consisted of a slow Introduction, generally repeated, and followed by an Allegro in the fugued style; and occasionally included a movement in one of the many dance-forms of the period, sometimes two pieces of this description. The development of the ballet and of the opera having been concurrent, and dance-pieces having formed important constituents of the opera itself, it was natural that the dramatic prelude should include similar features, and no incongruity was thereby involved, either in the overture, or the serious opera which it heralded, since the dance music of the period was generally of a stately, even solemn, kind. In style, the dramatic overture of the class now referred to—like the stage music which it preceded, and indeed all the secular compositions of the time, had little, if any, distinguishing characteristic to mark the difference between the secular and sacred styles. Music had been fostered and raised into the importance of an art by the Church, to whose service it had long been almost exclusively applied; and it retained a strong and pervading tinge of serious formalism during nearly a century of its earliest application to secular purposes, even to those of dramatic expression. The following quotations, first from Lulli's overture to 'Thésée' (1675), and next from that to 'Phaeton' (1683), will serve to indicate the style and form of the dramatic prelude as fixed by him. They are scored for stringed instruments. The overture to 'Thesée' begins as follows:—

This introduction is carried on for 16 bars further, with a repeat, and is followed by a movement 'Plus vite' (in all 33 bars), commencing as follows:—

The overture to 'Phaeton' starts thus:—

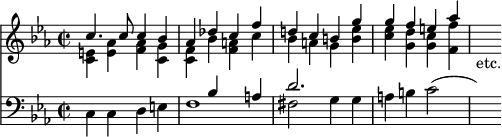

8 bars more follow in similar style, ending on the dominant—with a repeat—and then comes the quick movement, in free fugal style, commencing thus:—

![<< \new Staff { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/2 \partial 2 << \new Voice \relative g'' { \stemUp r8 g g[ g16 f] | e8 e e f16 e <d b>4. q8 | e[ c] g8.[ g16] <g g,>4 <b g>8. q16 | e8. d16 c8. b16 a4 ~ a16 c d e | s4_"etc." }

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemDown s2 | r8 c c d16 c r8 g g g16 f | e8[ e16 d] c[ d e f] d8[ d d d] | g8[ <g e>16 f] g[ f g e] c8[ a16 b] c[ b c a] }

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemDown s2 s1 c8[ c] e[ c] s2 | s f,4 f8 f } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass << \new Voice \relative g { \stemUp s2 | r2 r8 g g g | c c c c b8[ b16 a] g[ a b g] | c4 c8 c a[ f16 g] a8[ a] | s4 }

\new Voice \relative g { \stemDown s2 | R1 r2 r8 g g g | <e g>[ c16 d] q[ d q c] f8[ f f f] } >> } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/r/nrqwb1m700to9o5zkjlsbubu53324a6/nrqwb1m7.png)

There are 22 more bars of similar character, followed by a few marked 'lentement,' and a repeat.

In illustration of Lulli's influence in this respect on Purcell, the following extracts from the overture to Purcell's latest opera, 'Bonduca' (1695), may be adduced. It opens with a slow movement of 14 bars, beginning as follows:—

The Allegro commences thus:

This is carried on for 67 bars further, and merges into a closing Andante of 9 bars:—

As an example of the Italian style of operatic 'Sinfonia' the following quotations from the Neapolitan composer Alessandro Scarlatti are interesting, as showing an independence of the prevailing Lulli model that is remarkable considering the period. The extracts are from the orchestral prelude to his opera 'Il Prigioniero fortunato,' produced in 1698. They are given on the authority of a MS. formerly belonging to the celebrated double-bass player Dragonetti, and now in the British Museum (Add. MSS. 16,1 26). The score of the Sinfonia (or Overture) is for four trumpets and the usual string band, the violoncello part being marked 'con fagotto.' It begins Allegro, with a passage for ist and 2nd trumpet:—

This is repeated by the other two trumpets; and then the strings enter, as follows:—

Then the trumpets are used, in alternate pairs, after which come passages for strings on this figure:—

This is followed by 12 bars more in similar style; the trumpets being sometimes used in florid passages, and sometimes in harmony, in crotchets.

Then comes a movement 'Grave' for strings only, commencing thus:

19 more bars of a corresponding kind lead to a short 'Presto,' the 1st and 2nd trumpets in unison, and the 3rd and 4th also in unison:—

![<< \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \new Staff { \time 4/4 \key d \major << \new Voice \relative d'' { \stemUp d8.[ d16 d8. d16] e8.[ e16 e8. e16] | fis8.[ g16 a8. b16] e,4 r8 r16 a | \stemNeutral b8.[ a16 g8. b16] a8.[ g16 fis8. a16] | g8.[ fis16 e8. g16] fis4 s } \new Voice \relative f' { \stemDown fis4 r a r a } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key d \major << \new Voice \relative d' { \stemUp s1 s4 d cis s e s d s cis } \new Voice \relative d { \stemDown <d d'>4 r <cis cis'> r <d d'> fis a r | g r fis r | e r d'8.[ d16 d8. d16] } >> } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/x/sxfpafg9vwq4ie1i9sprcpyrw7x56o7/sxfpafg9.png)

6 more bars of a like kind follow, with a repeat; then a second part, consisting of similar passages, also repeated. This 'Sinfonia,' it will be seen, has no analogy with the stereotyped form of the Lulli overture.

The increased musical importance given to the Overture by Handel, while still adhering to the model fixed by Lulli, is proved even in his earliest specimens. A few quotations from the overture to 'Rinaldo,' the first Italian opera which he produced in England (1711), will serve as indications of the influence adverted to. The instrumentation is for string quartet, the 1st oboe playing with the 1st violin, and the 2nd oboe with the 2nd violin.

10 more bars follow, in a similar style; the movement is repeated, and closes on the dominant; after svhich comes a fugued Allegro, beginning as follows:—

This is carried on, with fluent power, for 33 bars more; a short slow movement follows, chiefly for the oboe; and the overture concludes with a 'Gigue.' Handel's inventive originality, and his independence of all prescribed forms in the choruses of his oratorios, stand in curious contrast to his subservience to precedent in his overtures; those to his Italian operas and those to his English oratorios being similar in form, style, and development; insomuch, indeed, that any one might be used with almost equal appropriateness for either purpose. There is a minuet extant which is said (we believe on the authority of the late Mr. Jones, organist of Canterbury Cathedral), to have been designed by Handel as the closing movement of the overture to the 'Messiah' when performed without the oratorio.[2] The first strain of this minuet is as follows:

As regards the Overture, then, Handel perfected the form first developed by Lulli, but cannot be considered as an inventor and grand originator, such as he appears in his sublime sacred choral writing.

Hitherto, as we have said, the dramatic Overture had no special relevance to the character and sentiment of the work which it preceded. The first step in this direction was taken by Gluck, who was for some time contemporaneous with Handel. It was he who first perceived, or at least realised, the importance of rendering the overture to a dramatic work analogous in style to the character of the music which is to follow. In the dedication of his 'Alceste' he refers to this among his other reforms in stage composition. [See Gluck, vol. i. 603b; Opera, vol. ii. 516a.] The French score of 'Alceste' includes, besides the invariable string quartet, flutes, oboes, a clarinet [App. p.737 "chalumeau"], and three trombones. Even Gluck, however, did not always identify the overture with the openi to which it belonged, so thoroughly as was afterwards done, by including a theme or themes in anticipation of the music which followed. Still, he certainly rendered the orchestral prelude what, as a writer has well said, a literary preface should be—'something analogous to the work itself, so that we may feel its want as a desire not elsewhere to be gratified.' His overtures to 'Alceste' and 'Iphigénie en Tauride' run continuously into the first scene of the opera and the latter is perhaps the most remarkable instance up to that time of special identification with the stage music which it heralds; inasmuch as it is a distinct foreshadowing of the opening storm scene of the opera into which the prelude is merged. Perhaps the finest specimen of the dramatic overture of the period, viewed as a distinct orchestral composition, is that of Gluck to his opera 'Iphigénie en Aulide.'

The influence of Gluck on Mozart is clearly to be traced in Mozart's first important opera, 'Idomeneo' (1781), the overture to which, both in beauty and power, is far in advance of any previous work of the kind; but, beyond a general nobility of style, it has no special dramatic character that inevitably associates it with the opera itself, though it is incorporated therewith by its continuance into the opening scene. In his next work, 'Die Entführung aus dem Serail' (.1782), Mozart has identified the prelude with the opera by the short incidental 'Andante' movement, anticipatory (in the minor key) of Belmont's aria 'Hier soil ich dich denn sehen.' In the overture to his 'Nozze di Figaro' (1786) he originally contemplated a similar interruption of the Allegro by a short slow movement—an intention afterwards happily abandoned. This overture is a veritable creation, that can only be sufficiently appreciated by a comparison of its brilliant outburst of genial and graceful vivacity with the vapid preludes to the comic operas of the day. In the overture to his 'Don Giovanni' (1787) we have a distinct identification with the opera by the use, in the introductory 'Andante,' of some of the wondrous music introducing the entry of the statue in the last scene. The solemn initial chords for trombones, and the fugal 'Allegro' of the overture to 'Die Zauberflöte' may be supposed to be suggestive of the religious element of the libretto; and this may be considered as the composer's masterpiece of its kind. Since Mozart's time the Overture has adopted the same general principles of form which govern the first movement of a Symphony or Sonata, without the repetition of the first section.

Reverting to the French school, we find a characteristic overture of Méhul's to his opera 'La Chasse du Jeune Henri' (1797), the prelude to which alone has survived. In this however, as in French music generally of that date (and even earlier), the influence of Haydn is distinctly apparent; his symphonies and quartets had met with immediate acceptance in Paris, one of the former indeed, entitled 'La Chasse,' having been composed 17 years before Méhul's opera. Cherubini, although Italian by birth, belongs to France; for all his great works were produced at Paris, and most of his life was passed there. This composer must be specially mentioned as having been one of the first to depart from the pattern of the Overture as fixed by Mozart. Cherubini indeed marks the transition point between the regular symmetry of the style of Mozart, and the coming disturbance of form effected by Beethoven. In the dramatic effect gained by the gradual and prolonged crescendo, both he and Méhul seem to have anticipated one of Rossini's favourite resources. This is specially observable in the overture to his opera 'Anacreon' (1803). Another feature is the abandonment of the Mozartian rule of giving the second subject (or episode) first in the dominant, and afterwards in the original key, as in the symphonies, quartets, and sonatas of the period. The next step in the development of the Overture was taken by Beethoven, who began by following the model left by Mozart, and carrying it to its highest development, as in the overture to the ballet of Prometheus (1800). In his other dramatic overtures, including those to von Collin's 'Coriolan' (1807) and to Goethe's 'Egmont' (1810), the great composer fully asserts his independence of form and precedent. But he had done so still earlier in the overture known as 'No. 3' of the four which he wrote for his opera 'Fidelio.' In this wonderful prelude (composed in 1806), Beethoven has apparently reached the highest possible point of dramatic expression, by foreshadowing the sublime heroism of Leonora's devoted affection for her husband, and indicating, as he does, the various phases of her grief at his disappearance, her search for him, his rescue by her from a dungeon and assassination, and their ultimate reunion and happiness. Here the stereotyped form of overture entirely disappears: the commencing scale passage, in descending octaves, suggesting the utterance of a wail of despairing grief, leads to the exquisite phrases of the 'Adagio' of Florestan's scena in the dungeon, followed by the passionate 'Allegro' which indicates the heroic purpose of Leonora; this movement including the spirit-stirring trumpet-call that proclaims the rescue of the imprisoned husband, and the whole winding up with a grandly exultant burst of joy; these leading features, and the grand development of the whole, constitute a dramatic prelude that is still unapproached. In 'No. 1' of these Fidelio Overtures (composed 1807) he has gone still further in the use of themes from the opera itself, and has employed a phrase which occurs in Florestan's Allegro to the words 'An angel Leonora,' in the coda of the overture, with very fine effect.

While in the magnificent work just described we must concede to Beethoven undivided pre-eminence in majesty and elevation of style, the palm, as to romanticism, and that powerful element of dramatic effect, 'local colour,' must be awarded to Weber. No subjects could well be more distinct than those of the Spanish drama 'Preciosa'(1820), the wild forest legend of North Germany, 'Der Freischütz' (1821), the chivalric subject of the book of 'Euryanthe' (1823), and the bright orientalism of 'Oberon' (1826). The overtures to these are too familiar to need specific reference; nor is it necessary to point out how vividly each is impressed with the character and tone of the opera to which it belongs. In each of them Weber has anticipated themes from the following stage music, while he has adhered to the Mozart model in the regular recurrence of the principal subject and the episode. His admirable use of the orchestra is specially evidenced in the 'Freischütz' overture, in which the tremolando passages for strings, the use of the chalumeau of the clarinet, and the employment of the drums, never fail to raise thrilling impressions of the supernatural. The incorporation of portions of the opera in the overture is so skilfully effected by Weber, that there is no impression of patchiness or want of spontaneous creation, as in the case of some other composers—Auber for instance and Rossini (excepting the latter's 'Tell'), whose overtures are too often like pot-pourris of the leading themes of the operas, loosely strung together, intrinsically charming and brilliantly scored, but seldom, if ever, especially dramatic. Most musical readers will remember Schubert's clever travestie of the last-named composer, in the 'Overture in the Italian style,' written off-hand by the former in 1817, during the rage for Rossini's music in Vienna.

Berlioz left two overtures to his opera of 'Benvenuto Cellini,' one bearing the name of the drama, the other called the 'Carnaval Romain,' and usually played as an entracte. The themes of both are derived more or less from the opera itself. Both are extraordinarily forcible and effective, abounding with the gorgeous instrumentation and bizarre treatment which are associated with the name of Berlioz.

Since Weber there has been no such fine example of the operatic overture—suggestive of and identified with the subsequent dramatic action—as that to Wagner's 'Tannhäuser,' in which, as in Weber's overtures, movements from the opera itself are amalgamated into a consistent whole, set off with every artifice of contrast and with the most splendid orchestration. A noticeable novelty in the construction of the operatic overture is to be found in Meyerbeer's incorporation of the choral 'Ave Maria' into his Overture to 'Dinorah' (Le Pardon de Ploermel).

In some of the modern operas, Italian and French (even of the grand and heroic class), the work is heralded merely by a trite and meagre introduction, of little more value or significance than the feeble Sinfonia of the earliest musical drama. Considering the extended development of modern opera, the absence of an overture of proportionate importance or (if a mere introductory prelude) one of such beauty and significance as that to Wagner's 'Lohengrin,' is a serious defect, and may generally be construed into an evidence of the composer's indolence, or of his want of power as an instrumental writer. Recurring to the comparison of a preface to an operatic overture, it may be said of the latter, as an author has well said of the former, that 'it should invite by its beauty, as an elegant porch announces the splendour of the interior.'

The development of the oratorio overture (as already implied) followed that of the operatic overture. Among prominent specimens of the former are those to the first and second parts of Spohr's 'Last Judgment' (the latter of which is entitled 'Symphony'); and the still finer overtures to Mendelssohn's 'St. Paul,' and 'Elijah,' this last presenting the specialty of being placed after the recitative passage with which the work really opens. Mr. Macfarren's overtures to his oratorios of 'John the Baptist,' 'The Resurrection,' and 'Joseph,' are all carefully designed to prepare the hearer for the work which follows, by employing themes from the oratorio itself, by introducing special features, as the Shofar-horn in 'John the Baptist,' or by general character and local colour, as in 'Joseph.' The introduction to Haydn's 'Creation'—a piece of 'programme music' illustrative of 'Chaos'—is a prelude not answering to the conditions of an overture properly so called, as does that of the same composer's 'Seasons,' which however is rather a cantata than an oratorio.

Reference has hitherto been made to the Overture only as the introduction to an opera, oratorio, or drama. The form and name have been however extensively applied during the present century to orchestral pieces intended merely for concert use, sometimes with no special purpose, in other instances bearing a specific title indicating the composer's intention to illustrate some poetical or legendary subject. Formerly a symphony, or one movement therefrom, was entitled 'Grand Overture,' or 'Overture,' in the concert programmes, according to whether the whole work, or only a portion thereof was used. Thus in the announcements of Salomon's London concerts (1791–4), Haydn's Symphonies, composed expressly for them, are generally so described. Among special examples of the Overture—properly so called—composed for independent performance are Beethoven's 'Weihe des Hauses,' written for the inauguration of the Josephsstadt Theatre in 1822; Mendelssohn's 'Midsummer Night's Dream Overture' (intended at first for concert use only, and afterwards supplemented by the exquisite stage music), and the same composer's 'Hebrides,' 'Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage,' and 'Melusine.' These overtures of Mendelssohn's are, indeed, unparalleled in their kind. It is scarcely necessary here to comment on the wondrous Shaksperean prelude, produced in the composer's boyhood as a concert overture, and in after years associated with the charming incidental music to the drama, passages of the overture occurring in the final chorus of fairies, and thus giving unity to the whole; nor will musical readers require to be reminded of the rare poetic and dramatic imagination, or the exquisite skill, by which the sombre romanticism of Scottish scenery, the contrasted suggestions of Goethe's poem, and the grace and passion of the Rhenish legend, are so happily illustrated in the other overtures referred to.

Schumann's Overtures of this class—'Bride of Messina,' 'Festival Overture,' 'Julius Cæsar,' 'Hermann and Dorothea'—though all very interesting are not very important; but in his 'Overture to Manfred' he has left one work of the highest significance and power, which will always maintain its position in the first rank of orchestral music. As the prelude, not to an opera, but to the incidental music to Byron's tragedy, this composition does not exactly fall in with either of the classes we have given. It is however dramatic and romantic enough for any drama, and its second subject is a quotation from a passage which occurs in the piece itself.

Berlioz's Overture 'Les Francs Juges,' embodying the idea of the Vehmgericht or secret tribunals of the Middle Ages, must not be omitted from our list, as a work of great length, great variety of ideas, and imposing effect.

The Concert-Overtures of Sterndale Bennett belong to a similar high order of imaginative thought, as exemplified in the well-known overtures entitled 'Parisina,' 'The Naiads,' and 'The Wood-Nymph,' and that string of musical pearls, the Fantasia-Overture illustrating passages from 'Paradise and the Peri.' Benedict's Overtures 'Der Prinz von Homburg' and 'Tempest,' Sullivan's 'In Memoriam' (in the climax of which the organ is introduced) and 'Di Ballo' (in dance rhythms), J. F. Barnett's 'Overture Symphonique,' Cusins's 'Les Travailleurs de la Mer,' Cowen's 'Festival Overture,' Gadsby's 'Andromeda,' Pierson's 'Faust' and 'Romeo and Juliet,' and many more, are all independent concert overtures.

The term has also been applied to original pieces for keyed instruments. Thus we have Bach's Overture in the French style; Handel's Overture in the first set of his Harpsichord Suites, and Mozart's imitation thereof among his pianoforte works. Each of these is the opening piece of a series. Beethoven has prefixed the word 'Overtura' to the Quartet-piece which originally formed the Finale to his BĊd; quartet (op. 131), but is now numbered separately as op. 133; but whether the term is meant to apply to the whole piece or only to the twenty-seven bars which introduce the fugue we have nothing to guide us. [See Entrée; Intrada; Introduction; Prelude; Symphony.][ H. J. L. ]