A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Symphony

SYMPHONY (Sinfonia, Sinfonie, Symphonie). The terms used in connection with any branch of art are commonly very vague and indefinite in the early stages of its history, and are applied without much discrimination to different things. In course of time men consequently find themselves in difficulties, and try, as far as their opportunities go, to limit the definition of the terms, and to confine them at least to things which are not obviously antagonistic. In the end, however, the process of sifting is rather guided by chance and external circumstances than determined by the meaning which theorists see to be the proper one; and the result is that the final meaning adopted by the world in general is frequently not only distinct from that which the original employers of the word intended, but also in doubtful conformity with its derivation. In the case of the word 'Symphony,' as with 'Sonata,' the meaning now accepted happens to be in very good accordance with its derivation, but it is considerably removed from the meaning which was originally attached to the word. It seems to have been used at first in a very general and comprehensive way, to express any portions of music or passages whatever which were thrown into relief as purely instrumental in works in which the chief interest was centred upon the voice or voices. Thus, in the operas, cantatas, and masses of the early part of the 17th century, the voices had the most important part of the work to do, and the instruments' chief business was to supply simple forms of harmony as accompaniment. If there were any little portions which the instruments played without the voices, these were indiscriminately called Symphonies; and under the same head were included such more particular forms as Overtures and Ritornelli. The first experimentalists in harmonic music generally dispensed with such independent instrumental passages altogether. For instance, most if not all of the cantatas of Cesti and Rossi[1] are devoid of either instrumental introduction or ritornel; and the same appears to have been the case with many of the operas of that time. There were however a few independent little instrumental movements even in the earliest operas. Peri's 'Euridice,' which stands almost at the head of the list (having been performed at Florence in 1600, as part of the festival in connection with the marriage of Henry IV of France and Mary de' Medici), contains a 'Sinfonia' for three flutes, which has a definite form of its own and is very characteristic of the time. The use of short instrumental passages, such as dances and introductions and ritornels, when once fairly begun, increased rapidly. Monteverde, who followed close upon Peri, made some use of them, and as the century grew older, they became a more and more important element in dramatic works, especially operas. The indiscriminate use of the word 'symphony,' to denote the passages of introduction to airs and recitatives, etc., lasted for a very long while, and got so far stereotyped in common usage that it was even applied to the instrumental portions of airs, etc., when played by a single performer. As an example may be quoted the following passage from a letter of Mozart's—'Sie (meaning Strinasacchi) spielt keine Note ohne Empfindung; sogar bei den Sinfonien spielte sie alles mit Expression,' etc.[2] With regard to this use of the term, it is not necessary to do more than point out the natural course by which the meaning began to be restricted. Lulli, Alessandro Scarlatti, and other great composers of operas in the 17th century, extended the appendages of airs to proportions relatively considerable, but there was a limit beyond which such dependent passages could not go. The independent instrumental portions, on the other hand, such as overtures or toccatas, or groups of ballet tunes, were in different circumstances, and could be expanded to a very much greater extent; and as they grew in importance the name 'Symphony' came by degrees to have a more special significance. The small instrumental appendages to the various airs and so forth were still symphonies in a general sense, but the Symphony par excellence was the introductory movement; and the more it grew in importance the more distinctive was this application of the term.

The earliest steps in the development of this portion of the opera are chiefly important as attempts to establish some broad principle of form; which for some time amounted to little more than the balance of short divisions, of slow and quick movement alternately. Lulli is credited with the invention of one form, which came ultimately to be known as the 'Ouverture à la manière Française.' The principles of this form, as generally understood, amounted to no more than the succession of a slow solid movement to begin with, followed by a quicker movement in a lighter style, and another slow movement, not so grave in character as the first, to conclude with. Lulli himself was not rigidly consistent in the adoption of this form. In some cases, as in 'Persée,' 'Thesée,' and 'Bellérophon,' there are two divisions only—the characteristic grave opening movement, and a short free fugal quick movement. 'Proserpine,' 'Phaéton,' 'Alceste,' and the Ballet piece, 'Le Triomphe de l'amour,' are characteristic examples of the complete model. These have a grave opening, which is repeated, and then the livelier central movement, which is followed by a division marked 'lentement'; and the last two divisions are repeated in full together. A few examples are occasionally to be met with by less famous composers than Lulli, which show how far the adoption of this form of overture or symphony became general in a short time. An opera called 'Venus and Adonis,' by Desmarests, of which there is a copy in the Library of the Royal College of Music, has the overture in this form. 'Amadis de Grèce,' by Des Touches, has the same, as far as can be judged from the character of the divisions; 'Albion and Albanius,' by Grabu, which was licensed for publication in England by Roger Lestrange in 1687, has clearly the same, and looks like an imitation direct from Lulli; and the 'Venus and Adonis' by Dr. John Blow, yet again the same. So the model must have been extensively appreciated. The most important composer, however, who followed Lulli in this matter, was Alessandro Scarlatti, who certainly varied and improved on the model both as regards the style and the form. In his opera of 'Flavio Cuniberto'[3] for instance, the 'Sinfonia avanti l'Opera' begins with a division marked grave, which is mainly based on simple canonical imitations, but has also broad expanses of contrasting keys. The style, for the time, is noble and rich, and very superior to Lulli's. The second division is a lively allegro, and the last a moderately quick minuet in 6-8 time. The 'Sinfonia' to his serenata 'Venere, Adone, Amore,' similarly has a Largo to begin with, a Presto in the middle, and a movement, not defined by a tempo, but clearly of moderate quickness, to end with. This form of 'Sinfonia' survived for a long while, and was expanded at times by a succession of dance movements, for which also Lulli supplied examples, and Handel at a later time more familiar types; but for the history of the modern symphony, a form which was distinguished from the other as the 'Italian Overture,' ultimately became of much greater importance.

This form appears in principle to be the exact opposite of the French Overture: it was similarly divided into three movements, but the first and last were quick and the central one slow. Who the originator of this form was it seems now impossible to decide; it certainly came into vogue very soon after the French Overture, and quickly supplanted it to a great extent. Certain details in its structure were better defined than in the earlier form, and the balance and distribution of characteristic features were alike freer and more comprehensive. The first allegro was generally in a square time and of solid character; the central movement aimed at expressiveness, and the last was a quick movement of relatively light character, generally in some combination of three feet. The history of its early development seems to be wrapped in obscurity, but from the moment of its appearance it has the traits of the modern orchestral symphony, and composers very soon obtained a remarkable degree of mastery over the form. It must have first come into definite acceptance about the end of the 17th or the beginning of the 18th century; and by the middle of the latter it had become almost a matter of course. Operas, and similar works by the most conspicuous composers of this time, in very great numbers, have the same form of overture. For instance, the two distinct versions of 'La Clemenza di Tito' by Hasse, 'Catone in Utica' by Leonardo Vinci (1728), the 'Hypermnestra,' 'Artaserse,' and others of Perez, Piccini's 'Didone,' Jomelli's 'Betulia liberata,' Sacchini's 'Œdipus,' Galuppi's 'Il mondo alla reversa'—produced the year before Haydn wrote his first symphony—and Adam Hiller's 'Lisuart und Dariolette,' 'Die Liebe auf dem Lande,' 'Der Krieg,' etc. And if a more conclusive proof of the general acceptance of the form were required, it would be found in the fact that Mozart adopted it in his boyish operas, 'La finta semplice' and 'Lucio Silla.' With the general adoption of the form came also a careful development of the internal structure of each separate movement, and also a gradual improvement both in the combination and treatment of the instruments employed. Lulli and Alessandro Scarlatti were for the most part satisfied with strings, which the former used crudely enough, but the latter with a good deal of perception of tone and appropriateness of style; sometimes with the addition of wind instruments. Early in the eighteenth century several wind instruments, such as oboes, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and flutes, were added, though not often all together; and they served, for the most part, chiefly to strengthen the strings and give contrasting degrees of full sound rather than contrasts of colour and tone. Equally important was the rapid improvement which took place simultaneously in internal structure; and in this case the development followed that of certain other departments of musical form. In fact the progress of the 'Sinfonia avanti l'Opera' in this respect was chiefly parallel to the development of the Clavier Sonata, which at this time was beginning to attain to clearness of outline, and a certain maturity of style. It will not be necessary here to repeat what has elsewhere been discussed from different points of view in the articles on Form, Sonata, and Suite; but it is important to realise that in point of time the form of this 'Sinfonia avanti l'Opera' did not lag behind in definition of outline and mastery of treatment; and it might be difficult to decide in which form (whether orchestral or clavier) the important detail first presents itself of defining the first and second principal sections by subjects decisively distinct. A marked improvement in various respects appears about the time when the symphony first began to be generally played apart from the opera; and the reasons for this are obvious. In the first place, as long as it was merely the appendage to a drama, less stress was laid upon it; and, what is more to the point, it is recorded that audiences were not by any means particularly attentive to the instrumental portion of the work. The description given of the behaviour of the public at some of the most important theatres in Europe in the middle of the eighteenth century, seems to correspond to the descriptions which are given of the audience at the Italian Operas in England in the latter half of the nineteenth. Burney, in the account of his tour, refers to this more than once. In the first volume he says, 'The music at the theatres in Italy seems but an excuse for people to assemble together, their attention being chiefly placed on play and conversation, even during the performance of a serious opera.' In another place he describes the card tables, and the way in which the 'people of quality' reserved their attention for a favourite air or two, or the performance of a favourite singer. The rest, including the overture, they did not regard as of much consequence, and hence the composers had but little inducement to put out the best of their powers. It may have been partly on this account that they took very little pains to connect these overtures or symphonies with the opera, either by character or feature. They allowed it to become almost a settled principle that they should be independent in matter; and consequently there was very little difficulty in accepting them as independent instrumental pieces. It naturally followed as it did later with another form of overture. The 'Symphonies' which had more attractive qualities were played apart from the operas, in concerts; and the precedent being thereby established, the step to writing independent works on similar lines was but short; and it was natural that, as undivided attention would now be given to them, and they were no more in a secondary position in connection with the opera, composers should take more pains both in the structure and in the choice of their musical material. The Symphony had however reached a considerable pitch of development before the emancipation took place; and this development was connected with the progress of certain other musical forms besides the Sonata, already referred to.

It will accordingly be convenient, before proceeding further with the direct history of the Symphony, to consider some of the more important of these early branches of Musical Art. In the early harmonic times the relationships of nearly all the different branches of composition were close. The Symphony was related even to the early Madrigals, through the 'Sonate da Chiesa,' which adopted the Canzona or instrumental version of the Madrigal as a second movement. It was also closely related to the early Fantasias, as the earliest experiments in instrumental music, in which some of the technical necessities of that department were grappled with. It was directly connected with the vocal portions of the early operas, such as airs and recitatives, and derived from them many of the mechanical forms of cadence and harmony which for a long time were a necessary part of its form. The solo Clavier Suite had also something to do with it, but not so much as might be expected. As has been pointed out elsewhere, the suite-form, being very simple in its principle, attained to definition very early, while the sonata-form, which characterised the richest period of harmonic music, was still struggling in elementary stages. The ultimate basis of the suite-form is a contrast of dance tunes; but in the typical early symphony the dance-tunes are almost invariably avoided. When the Symphony was expanded by the addition of the Minuet and Trio, a bond of connection seemed to be established; but still this bond was not at all a vital one, for the Minuet is one of the least characteristic elements of the suite-form proper, being clearly of less ancient lineage and type than the Allemande, Courante, Sarabande, or Gigue, or even the Gavotte and Bourrée, which were classed with it, as Intermezzi or Galanterien. The form of the Clavier Suite movements was in fact too inelastic to admit of such expansion and development as was required in the orchestral works, and the type did not supply the characteristic technical qualities which would be of service in their development. The position of Bach's Orchestral Suites was somewhat different; and it appears that he himself called them Overtures. Dehn, in his preface to the first edition printed, says that the separate MS. parts in the Bach archives at Hamburg, from which he took that in C, have the distinctive characteristics of the handwriting of John Sebastian, and have for title 'Ouverture pour 2 Violons,' etc.; and that another MS., probably copied from these, has the title 'Suite pour Orchestre.' This throws a certain light upon Bach's position. It is obvious that in several departments of instrumental music he took the French for his models rather than the Italians. In the Suite he followed Couperin, and in the Overture he also followed French models. These therefore appear as attempts to develop an independent orchestral work analogous to the Symphony, upon the basis of a form which had the same reason for existence and the same general purpose as the Italian Overture, but a distinctly different general outline. Their chief connection with the actual development of the modern symphony lies in the treatment of the instruments; for all experiments, even on different lines, if they have a common quality or principle, must react upon one another in those respects.

Another branch of art which had close connection with the early symphonies was the Concerto. Works under this name were not by any means invariably meant to be show pieces for solo instruments, as modern concertos are; and sometimes the name was used as almost synonymous with symphony. The earliest concertos seem to have been works in which groups of 'solo' and 'ripieno' instruments were used, chiefly to obtain contrasts of fullness of tone. For instance, a set of six concertos by Alessandro Scarlatti, for two violins and cello, 'soli,' and two violins, tenor, and bass, 'ripieni,' present no distinction of style between one group and the other. The accompanying instruments for the most part merely double the solo parts, and leave off either to lessen the sound here and there, or because the passages happen to go a little higher than usual, or to be a little difficult for the average violin-players of that time. When the intention is to vary the quality of sound as well, the element of what is called instrumentation is introduced, and this is one of the earliest phases of that element which can be traced in music. The order of movements and the style of them are generally after the manner of the Sonate da Chiesa, and therefore do not present any close analogy with the subject of this article. But very soon after the time of Corelli and Alessandro Scarlatti the form of the Italian overture was adopted for concertos, and about the same time they began to show traces of becoming show-pieces for great performers. Allusions to the performance of concertos by great violin-players in the churches form a familiar feature in the musical literature of the 18th century, and the three-movement-form (to all intents exactly like that of the symphonies) seems to have been adopted early. This evidently points to the fact that this form appealed to the instincts of composers generally, as the most promising for free expression of their musical thoughts. It may seem curious that J. S. Bach, who followed French models in some important departments of instrumental music, should exclusively have followed Italian models in this. But in reality it appears to have been a matter of chance with him; he always followed the best models which came to his hand. In this department the Italians excelled; and Bach therefore followed them, and left the most important early specimens of this kind remaining—almost all in the three movement-form, which was becoming the set order for symphonies. Setting aside those specially imitated from Vivaldi, there are at least twenty concertos by him for all sorts of solo instruments and combinations of solo instruments in this same form. It cannot therefore be doubted that some of the development of the symphony-form took place in this department. But Bach never to any noticeable extent yielded to the tendency to break the movements up into sections with corresponding tunes; and this distinguishes his work in a very marked manner from that of the generation of composers who followed him. His art belongs in reality to a different stratum from that which produced the greater forms of abstract instrumental music. It is probable that his form of art could not without some modification have produced the great orchestral symphonies. In order to get to these, composers had to go to a different, and for some time a decidedly lower, level. It was much the same process as had been gone through before. After Palestrina a backward move was necessary to make it possible to arrive at the art of Bach and Handel. After Bach men had to take up a lower line in order to get to Beethoven. In the latter case it was necessary to go through the elementary stages of defining the various contrasting sections of a movement, and finding that form of harmonic treatment which admitted the great effects of colour or varieties of tone in the mass, as well as in the separate lines of the counterpoint. Bach's position was so immensely high that several generations had to pass before men were able to follow on his lines and adopt his principles in harmonic music. The generation that followed him showed scarcely any trace of his influence. Even before be had passed away the new tendencies of music were strongly apparent, and much of the elementary work of the modern sonata form of art had been done on different lines from his own.

The 'Sinfonia avanti l'Opera' was clearly by this time sufficiently independent and complete to be appreciated without the opera, and without either name or programme to explain its meaning; and within a very short period the demand for these sinfonias became very great. Burney's tours in search of materials for his History, in France, Italy, Holland, and Germany, were made in 1770 and 72, before Haydn had written any of his greater symphonies, and while Mozart was still a boy. His allusions to independent 'symphonies' are very frequent. Among those whose works he mentions with most favour are Stamitz, Emmanuel Bach, Christian Bach, and Abel. Works of the kind by these composers and many others of note are to be seen in great numbers in sets of part-books in the British Museum. These furnish most excellent materials for judging of the status of the Symphony in the early stages of its independent existence. The two most important points which they illustrate are the development of instrumentation, and the definition of form. They appear to have been generally written in eight parts. Most of them are scored for two violins, viola, and bass; two hautboys, or two flutes, and two 'cors de chasse.' This is the case in the six symphonies of opus 3 of John Christian Bach; the six of Abel's opus 10, the six of Stamitz's opus 9, opus 13, and opus 16; also in a set of 'Overtures in 8 parts' by Arne, which must have been early in the field, as the licence from George II, printed in full at the beginning of the first violin part, is dated January 17+40/41. The same orchestration is found in many symphonies by Galuppi, Ditters, Schwindl, and others. Wagenseil, who must have been the oldest of this group of composers (having been born in the 17th century, within six years after Handel, Scarlatti, and Bach), wrote several quite in the characteristic harmonic style, 'à 4 parties obligées avec Cors de Chasse ad libitum.' The treatment of the instruments in these early examples is rather crude and stiff. The violins are almost always playing, and the hautboys or flutes are only used to reinforce them at times as the 'ripieni' instruments did in the early concertos, while the horns serve to hold on the harmonies. The first stages of improvement are noticeable in such details as the independent treatment of the strings. In the 'symphonies before the opera' the violas were cared for so little that in many cases[4] not more than half-a-dozen bars are written in, all the rest being merely 'col basso.' As examples of this in works of more or less illustrious writers may be mentioned the 'Sinfonias' to Jomelli's 'Passione' and 'Betulia Liberata,' Sacchini's 'Œdipus,' and Sarti's 'Giulio Sabino.' One of the many honours attributed to Stamitz by his admiring contemporaries was that he made the violas independent of the basses. This may seem a trivial detail, but it is only by such details, and the way in which they struck contemporary writers, that the character of the gradual progress in instrumental composition can now be understood.

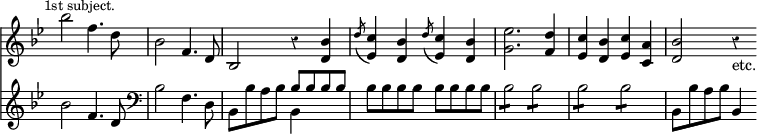

The general outlines of the form were extremely regular. The three movements as above described were almost invariable, the first being a vigorous broad allegro, the second the sentimental slow movement, and the third the lively vivace. The progress of internal structure is at first chiefly noticeable in the first movement. In the early examples this is always condensed as much as possible, the balance of subjects is not very clearly realisable, and there is hardly ever a double bar or repeat of the first half of the movement. The divisions of key, the short 'working out' portion, and the recapitulation, are generally present, but not pointedly defined. Examples of this condition of things are supplied by some MS. symphonies by Paradisi in the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, which in other respects possess excellent and characteristically modern traits. The first thing attained seems to have been the relative definition and balance of the two subjects. In Stamitz, Abel, J. C. Bach, and Wagenseil, this is already commonly met with. The following examples from the first movement of the fifth symphony of Stamitz's opus 9 illustrate both the style and the degree of contrast between the two principal subjects,

The style is a little heavy, and the motion constrained, but the general character is solid and dignified. The last movements of this period are curiously suggestive of some familiar examples of a maturer time; very gay and obvious, and very definite in outline. The following is very characteristic of Abel:—

It is a noticeable fact in connection with the genealogy of these works, that they are almost as frequently entitled 'Overture' as 'Symphony'; sometimes the same work is called by the one name outside and the other in; and this is the case also with some of the earlier and slighter symphonies of Haydn, which must have made their appearance about this period. One further point which it is of importance to note is that in some of Stamitz's symphonies the complete form of the mature period is found. One in D is most complete in every respect. The first movement is Allegro with double bars and repeats in regular binary form; the second is an Andante in G, the third a Minuet and Trio, and the fourth a Presto. Another in E♭ (which is called no. 7 in the part-books) and another in F (not definable) have also the Minuet and Trio. A few others by Schwindl and Ditters have the same, but it is impossible to get even approximately to the date of their production, and therefore little inference can be framed upon the circumstance, beyond the fact that composers were beginning to recognise the fourth movement as a desirable ingredient.

Another composer who precedes Haydn in time as well as in style is Emmanuel Bach. He was his senior in years, and began writing symphonies in 1741, when Haydn was only nine years old. His most important symphonies were produced in 1776; while Haydn's most important examples were not produced till after 1790. In style Emmanuel Bach stands singularly alone, at least in his finest examples. It looks almost as if he purposely avoided the form which by 1776 must have been familiar to the musical world. It has been shown that the binary form was employed by some of his contemporaries in their orchestral works, but he seems determinedly to avoid it in the first movements of the works of that year. His object seems to have been to produce striking and clearly outlined passages, and to balance and contrast them one with another according to his fancy, and with little regard to any systematic distribution of the successions of key. The boldest and most striking subject is the first of the Symphony in D:—

The opening passages of that in E♭ are hardly less emphatic. They have little connection with the tendencies of his contemporaries, but seem in every respect an experiment on independent lines, in which the interest depends upon the vigour of the thoughts and the unexpected turns of the modulations; and the result is certainly rather fragmentary and disconnected. The slow movement is commonly connected with the first and last either by a special transitional passage, or by a turn of modulation and a half close. It is short and dependent in its character, but graceful and melodious. The last is much more systematic in structure than the first; sometimes in definite binary form, as was the case with the early violin sonatas. In orchestration and general style of expression these works seem immensely superior to the other early symphonies which have been described. They are scored for horns, flutes, oboi, fagotto, strings, with a figured bass for 'cembalo,' which in the symphonies previously noticed does not always appear. There is an abundance of unison and octave passages for the strings, but there is also good free writing, and contrasts between wind and strings; the wind being occasionally left quite alone. All the instruments come in occasionally for special employment, and considering the proportions of the orchestras of the time Bach's effects must have been generally clear and good. The following is a good specimen of his scoring of an ordinary full passage:—

![{ << \new Staff << \key ees \major \time 2/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Voice \relative e'' { \stemUp

ees4^\markup \small "Corni in E♭" r8 ees | d r d r | c r r c }

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemDown

c4 s8 c | c s ees, s | ees s s ees' } >>

\new Staff << \key ees \major

\new Voice \relative g'' { \stemUp

g4^\markup \small "Flauti" ees' ^~ | ees d ^~ | d c }

\new Voice \relative g'' { \stemDown g2 f ees } >>

\new Staff << \key ees \major

\new Voice \relative g'' { \stemUp

g2^\markup \small "Oboi" f ees }

\new Voice \relative b' { \stemDown

bes4 ees _~ | ees d _~ d c } >>

\new Staff \relative g'' { \key ees \major

g32^\markup \small "Violini 1 & 2" ees d ees

\repeat unfold 3 { g[ ees d ees] }

f ees d ees f[ ees d ees] f d c d f[ d c d] |

ees[ d c d] ees d c d ees c b c ees[ c b c] }

\new Staff \relative e' { \clef alto \key ees \major

ees4^\markup \small "Viola" r8 c' | c c g g | g g r g }

\new Staff \relative e { \clef bass \key ees \major

ees4^\markup \small { \column { "Celli" \vspace #0.1 "Fagotto" "Bassi e Cembalo" } } r8 c' |

a4^\markup \small \italic "ten." b\trill | c8 c, r ees }

\figures { s2 <5>4 <5> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/i/ai0gqlh2swyizzedcmv4wfkce6w3471/ai0gqlh2.png)

It has sometimes been said that Haydn was chiefly influenced by Emmanuel Bach, and Mozart by John Christian Bach. At the present time, and in relation to symphonies, it is easier to understand the latter case than the former. In both cases the influence is more likely to be traced in clavier works than in those for orchestra. For Haydn's style and treatment of form bear far more resemblance to most of the other composers whose works have been referred to, than to Emmanuel Bach. There are certain kinds of forcible expression and ingenious turns of modulation which Haydn may have learnt from him; but their best orchestral works seem to belong to quite distinct families. Haydn's first symphony was written in 1759 for Count Morzin. Like many other of his early works it does not seem discoverable in print in this country. But it is said by Pohl,[5] who must have seen it somewhere in Germany, to be 'a small work in three movements for 2 violins, viola, bass, 2 oboes, and 2 horns'; from which particulars it would appear to correspond exactly in externals to the examples above described of Abel's and J. C. Bach's, etc. In the course of the next few years he added many more; most of which appear to have been slight and of no great historical importance, while the few which present peculiarities are so far isolated in those respects that they do not throw much light upon the course of his development, or upon his share in building up the art-form of the Symphony. Of such a kind is the movement (dramatic in character, and including long passages of recitative) in the Symphony in C, which he wrote as early as 1761.[6] For, though this kind of movement is found in instrumental works of an earlier period, its appearance in such a manner in a symphony is too rare to have any special historical bearings. The course of his development was gradual and regular. He seems to have been content with steadily improving the edifice of his predecessors, and with few exceptions to have followed their lines. A great deal is frequently attributed to his connection with the complete musical establishment which Prince Esterhazy set up at his great palace at Esterház; where Haydn certainly had opportunities which have been the lot of scarcely any other composer who ever lived. He is described as making experiments in orchestration, and ringing the bell for the band to come and try them; and, though this may not be absolutely true in fact, there can scarcely be a doubt that the very great improvements which he effected in every department of orchestration may to a great extent be attributed to the facilities for testing his works which he enjoyed. At the same time the really important portion of his compositions were not produced till his patron, Prince Nicolaus Esterhazy, was dead, and the musical establishment broken up; nor, it must be remembered, till after that strange and important episode in Haydn's life, the rapid flitting of Mozart across the scene. When Haydn wrote his first symphony, Mozart was only three years old; and Mozart died in the very year in which the famous Salomon concerts in London, for which Haydn wrote nearly all his finest symphonies, began. Mozart's work therefore comes between Haydn's lighter period and his greatest achievements; and his symphonies are in some respects prior to Haydn's, and certainly had effect upon his later works of all kinds.

According to Köchel, Mozart wrote altogether forty-nine symphonies. The first, in E♭, was written in London in 1764, when he was eight years old, and only five years after Haydn wrote his first. It was on the same pattern as those which have been fully described above, being in three movements and scored for the usual set of instruments namely, two violins, viola, bass, two oboes and two horns. Three more followed in close succession, in one of which clarinets are introduced instead of oboes, and a bassoon is added to the usual group of eight instruments. In these works striking originality of purpose or style is hardly to be looked for, and it was not for some time that Mozart's powers in instrumental music reached a pitch of development which is historically important; but it is nevertheless astonishing to see how early he developed a free and even rich style in managing his orchestral resources. With regard to the character of these and all but a few of the rest, it is necessary to keep in mind that a symphony at that time was a very much less important matter than it became fifty years later. The manner in which symphonies were poured out, in sets of six and otherwise, by numerous composers during the latter half of the eighteenth century, puts utterly out of the question the loftiness of aim and purpose which has become a necessity since the early years of the present century. They were all rather slight works on familiar lines, with which for the time being composers and public were alike quite content; and neither Haydn nor Mozart in their early specimens seem to have specially exerted themselves. The general survey of Mozart's symphonies presents a certain number of facts which are worth noting for their bearing upon the history of this form of art. The second symphony he wrote had a minuet and trio; but it is hardly possible that he can have regarded this as an important point, since he afterwards wrote seventeen others without them; and these spread over the whole period of his activity, for even in that which he wrote at Prague in 1786, and which is last but three in the whole series, the minuet and trio are absent. Besides this fact, which at once connects them with the examples by other composers previously discussed, there is the yet more noticeable one that more than twenty of the series are written for the same peculiar little group of instruments, viz. the four strings, a pair of oboes or flutes, and a pair of horns. Although he used clarinets so early as his third symphony, he never employed them again till his thirty-ninth, which was written for Paris, and is almost more fully scored than any. In the whole forty-nine, in fact, he only used clarinets five times, and in one of these cases (viz. the well-known G minor) they were added after he had finished the score. Even bassoons are not common; the most frequent addition to the little nucleus of oboes or flutes and horns being trumpets and drums. The two which are most fully scored are the Parisian, in D, just alluded to, which was written in 1778, and that in E♭, which was written in Vienna in 1788, and stands first in the famous triad. These facts explain to a certain extent how it was possible to write such an extraordinary number in so short a space of time. Mozart's most continuously prolific period in this branch of art seems to have been when he had returned to Salzburg in 1771; for between July in that year and the beginning of 1773, it appears to be proved that he produced no less than fourteen. But this feat is fairly surpassed in another sense by the production of the last three in three successive months, June, July, and August, 1788; since the musical calibre of these is so immensely superior to that of the earlier ones.

One detail of comparison between Mozart's ways and Haydn's is curious. Haydn began to use introductory adagios very early, and used them so often that they became quite a characteristic feature in his plan. Mozart, on the other hand, did not use one until his 44th Symphony, written in 1783. What was the origin of Haydn's employment of them is uncertain. The causes that have been suggested are not altogether satisfactory. In the orthodox form of symphony, as written by the numerous composers of his early days, the opening adagio is not found. He may possibly have observed that it was a useful factor in a certain class of overtures, and then have used it as an experiment in symphonies, and finding it answer, may have adopted the expedient generally in succeeding works of the kind. It seems likely that Mozart adopted it from Haydn, as its first appearance (in the symphony which is believed to have been composed at Linz for Count Thun) coincides with the period in which he is considered to have been first strongly influenced by Haydn.

The influence of these two great composers upon one another is extremely interesting and curious, more especially as it did not take effect till comparatively late in their artistic careers. They both began working in the general direction of their time, under the influences which have been already referred to. In the department of symphony each was considerably influenced after a time by a special circumstance of his life; Haydn by the appointment to Esterház before alluded to, and the opportunities it afforded him of orchestral experiment; and Mozart by his stay at Mannheim in 1777. For it appears most likely that the superior abilities of the Mannheim orchestra for dealing with purely instrumental music, and the traditions of Stamitz, who had there effected his share in the history of the Symphony, opened Mozart's eyes to the possibilities of orchestral performance, and encouraged him to a freer style of composition and more elaborate treatment of the orchestra than he had up to that time attempted. The Mannheim band had in fact been long considered the finest in Europe; and in certain things, such as attention to nuances (which in early orchestral works had been looked upon as either unnecessary or out of place), they and their conductors had been important pioneers; and thus Mozart must certainly have had his ideas on such heads a good deal expanded. The qualities of the symphony produced in Paris early in the next year were probably the first fruits of these circumstances; and it happens that while this symphony is the first of his which has maintained a definite position among the important landmarks of art, it is also the first in which he uses orchestral forces approaching to those commonly employed for symphonies since the latter part of the last century.

Both Haydn and Mozart, in the course of their respective careers, made decided progress in managing the orchestra, both as regards the treatment of individual instruments, and the distribution of the details of musical interest among them. It has been already pointed out that one of the earliest expedients by which contrast of effect was attempted by writers for combinations of instruments, was the careful distribution of portions for 'solo' and 'ripieno' instruments, as illustrated by Scarlatti's and later concertos. In J. S. Bach's treatment of the orchestra the same characteristic is familiar. The long duets for oboes, flutes, or bassoons, and the solos for horn or violin, or viola da gamba, which continue throughout whole recitatives or arias, all have this same principle at bottom. Composers had still to learn the free and yet well-balanced management of their string forces, and to attain the mean between the use of wind instruments merely to strengthen the strings and their use as solo instruments in long independent passages. In Haydn's early symphonies the old traditions are most apparent. The balance between the different forces of the orchestra is as yet both crude and obvious. In the symphony called 'Le Matin' for instance, which appears to have been among the earliest, the second violins play with the first, and the violas with the basses to a very marked extent—in the first movement almost throughout. This first movement, again, begins with a solo for flute. The slow movement, which is divided into adagio and andante, has no wind instruments at all, but there is a violin solo throughout the middle portion. In the minuet a contrast is attained by a long passage for wind band alone (as in J. S. Bach's 2nd Bourrée to the 'Ouverture' in C major); and the trio consists of a long and elaborate solo for bassoon. Haydn early began experiments in various uses of his orchestra, and his ways of grouping his solo instruments for effect are often curious and original. C. F. Pohl, in his life of him, prints from the MS. parts a charming slow movement from a B♭ symphony, which was probably written in 1766 or 1767. It illustrates in a singular way how Haydn at first endeavoured to obtain a special effect without ceasing to conform to familiar methods of treating his strings. The movement is scored for first and second violins, violas, solo violoncello and bass, all 'con sordini.' The first and second violins play in unison thoughout, and the cello plays the tune with them an octave lower, while the violas play in octaves with the bass all but two or three bars of cadence; so that in reality there are scarcely ever more than two parts playing at a time. The following example will show the style:—

Towards a really free treatment of his forces he seems, however, to have been led on insensibly and by very slow degrees. For over twenty years of symphony-writing the same limited treatment of strings and the same kind of solo passages are commonly to be met with. But there is a growing tendency to make the wind and the lower and inner strings more and more independent, and to individualise the style of each within proportionate bounds. A fine symphony (in E minor, 'Letter I') which appears to date from 1772, is a good specimen of Haydn's intermediate stage. The strings play almost incessantly throughout, and the wind either doubles the string parts to enrich and reinforce them, or else has long holding notes while the strings play characteristic figures. The following passage from the last movement will serve to illustrate pretty clearly the stage of orchestral expression to which Haydn had at that time arrived:—

In the course of the following ten years the progress was slow but steady. No doubt many other composers were writing symphonies besides Haydn and Mozart, and were, like them, improving that branch of art. Unfortunately the difficulty of fixing the dates of their productions is almost insuperable; and so their greater representatives come to be regarded, not only as giving an epitome of the history of the epoch, but as comprising it in themselves. Mozart's first specially notable symphony falls in 1778. This was the one which he wrote for Paris after his experiences at Mannheim; and some of his Mannheim friends who happened to be in Paris with him assisted at the performance. It is in almost every respect a very great advance upon Haydn's E minor Symphony, just quoted. The treatment of the instruments is very much freer, and more individually characteristic. It marks an important step in the transition from the kind of symphony in which the music appears to have been conceived almost entirely for violins, with wind subordinate, except in special solo passages, to the kind in which the original conception in respect of subjects, episodes and development, embraced all the forces, including the wind instruments. The first eight bars of Mozart's symphony are sufficient to illustrate the nature of the artistic tendency. In the firm and dignified beginning of the principal subject, the strings, with flutes and bassoons, are all in unison for three bars, and a good body of wind instruments gives the full chord. Then the upper strings are left alone for a couple of bars in octaves, and are accompanied in their short closing phrase by an independent full chord of wind instruments, piano. This chord is repeated in the same form of rhythm as that which marks the first bars of the principal subject, and has therefore at once musical sense and relevancy, besides supplying the necessary full harmony. In the subsidiary subject by which the first section is carried on, the quick lively passages of the strings are accompanied by short figures for flute and horns, with their own independent musical significance. In the second subject proper, which is derived from this subsidiary, an excellent balance of colour is obtained by pairs of wind instruments in octaves, answering with an independent and very characteristic phrase of their own the group of strings which give out the first part of the subject. The same well-balanced method is observed throughout. In the working out of this movement almost all the instruments have something special and relevant of their own to do, so that it is made to seem as if the conception were exactly apportioned to the forces which were meant to utter it. The same criticisms apply to all the rest of the symphony. The slow movement has beautiful independent figures and phrases for the wind instruments, so interwoven with the body of the movement that they supply necessary elements of colour and fulness of harmony, without appearing either as definite solos or as meaningless holding notes. The fresh and merry last movement has much the same characteristics as the first in the matter of instrumental utterance, and in its working-out section all the forces have, if anything, even more independent work of their own to do, while still supplying their appropriate ingredients to the sum total of sound.

The succeeding ten years saw all the rest of the work Mozart was destined to do in the department of symphony; much of it showing in turn an advance on the Paris Symphony, inasmuch as the principles there shown were worked out to greater fullness and perfection, while the musical spirit attained a more definite richness, and escaped further from the formalism which characterises the previous generation. Among these symphonies the most important are the following: a considerable one (in E♭) composed at Salzburg in 1780; the 'Haffner' (in D), which was a modification of a serenade, and had originally more than the usual group of movements; the 'Linz' Symphony (in C; 'No. 6'); and the last four, the crown of the whole series. The first of these (in D major) was written for Prague in 1786, and was received there with immense favour in January 1787. It appears to be far in advance of all its predecessors in freedom and clearness of instrumentation, in the breadth and musical significance of the subjects, and in richness and balance of form. It is one of the few of Mozart's which open with an adagio, and that too of unusual proportions; but it has no minuet and trio. This symphony was in its turn eclipsed by the three great ones in E flat, G minor, and C, which were composed at Vienna in June, July and August, 1788. These symphonies are almost the first in which certain qualities of musical expression and a certain method in their treatment stand prominent in the manner which was destined to become characteristic of the great works of the early part of the nineteenth century. Mozart having mastered the principle upon which the mature art-form of symphony was to be attacked, had greater freedom for the expression of his intrinsically musical ideas, and could emphasise more freely and consistently the typical characteristics which his inspiration led him to adopt in developing his ideas. It must not, however, be supposed that this principle is to be found for the first time in these works. They find their counterparts in works of Haydn's of a much earlier date; only, inasmuch as the art-form was then less mature, the element of formalism is too strong to admit of the musical or poetical intention being so clearly realised. It is of course impossible to put into words with certainty the inherent characteristics of these or any other later works on the same lines; but that they are felt to have such characteristics is indisputable, and their perfection as works of art, which is so commonly insisted on, could not exist if it were not so. Among the many writers who have tried in some way to describe them, probably the best and most responsible is Otto Jahn. Of the first of the group (that in E♭), he says, 'We find the expression of perfect happiness in the charm of euphony' which is one of the marked external characteristics of the whole work. 'The feeling of pride in the consciousness of power shines through the magnificent introduction, while the Allegro expresses the purest pleasure, now in frolicsome joy, now in active excitement, and now in noble and dignified composure. Some shadows appear, it is true, in the Andante, but they only serve to throw into stronger relief the mild serenity of a mind communing with itself and rejoicing in the peace which fills it. This is the true source of the cheerful transport which rules the last movement, rejoicing in its own strength and in the joy of being.' Whether this is all perfectly true or not is of less consequence than the fact that a consistent and uniform style and object can be discerned through the whole work, and that it admits of an approximate description in words, without either straining or violating familiar impressions.

The second of the great symphonic trilogy—that in G minor—has a still clearer meaning. The contrast with the E♭ is strong, for in no symphony of Mozart's is there so much sadness and regretfulness. This element also accounts for the fact that it is the most modern of his symphonies, and shows most human nature. E. J. A. Hoffmann (writing in a spirit very different from that of Jahn) says of it, 'Love and melancholy breathe forth in purest spirit tones; we feel ourselves drawn with inexpressible longing towards the forms which beckon us to join them in their flight through the clouds to another sphere.' Jahn agrees in attributing to it a character of sorrow and complaining; and there can hardly be a doubt that the tonality as well as the style, and such characteristic features as occur incidentally, would all favour the idea that Mozart's inspiration took a sad cast, and maintained it so far throughout; so that, notwithstanding the formal passages which occasionally make their appearance at the closes, the whole work may without violation of probability receive a consistent psychological explanation. Even the orchestration seems appropriate from this point of view, since the prevailing effect is far less soft and smooth than that of the previous symphony. A detail of historical interest in connection with this work is the fact that Mozart originally wrote it without clarinets, and added them afterwards for a performance at which it may be presumed they happened to be specially available. He did this by taking a separate piece of paper and rearranging the oboe parts, sometimes combining the instruments and sometimes distributing the parts between the two, with due regard to their characteristic styles of utterance.

The last of Mozart's symphonies has so obvious and distinctive a character throughout, that popular estimation has accepted the definite name 'Jupiter' as conveying the prevalent feeling about it. In this there is far less human sentiment than in the G minor. In fact, Mozart appears to have aimed at something lofty and self-contained, and therefore precluding the shade of sadness which is an element almost indispensable to strong human sympathy. When he descends from this distant height, he assumes a cheerful and sometimes playful vein, as in the second principal subject of the first movement, and in the subsidiary or cadence subject that follows it. This may not be altogether in accordance with what is popularly meant by the name 'Jupiter,' though that deity appears to have been capable of a good deal of levity in his time; but it has the virtue of supplying admirable contrast to the main subjects of the section; and it is so far in consonance with them that there is no actual reversal of feeling in passing from one to the other. The slow movement has an appropriate dignity which keeps it in character, and reaches, in parts, a considerable degree of passion, which brings it nearer to human sympathy than the other movements. The Minuet and the Trio again show cheerful serenity, and the last movement, with its elaborate fugal treatment, has a vigorous austerity, which is an excellent balance to the character of the first movement. The scoring, especially in the first and last movements, is fuller than is usual with Mozart, and produces effects of strong and clear sound; and it is also admirably in character with the spirit of dignity and loftiness which seems to be aimed at in the greater portion of the musical subjects and figures. In these later symphonies Mozart certainly reached a far higher pitch of art in the department of instrumental music than any hitherto arrived at. The characteristics of his attainments may be described as a freedom of style in the ideas, freedom in the treatment of the various parts of the score, and independence and appropriateness of expression in the management of the various groups of instruments employed. In comparison with the works of his predecessors, and with his own and Haydn's earlier compositions there is throughout a most remarkable advance in vitality. The distribution of certain cadences and passages of tutti still appear to modern ears formal; but compared with the immature formalism of expression, even in principal ideas, which was prevalent twenty or even ten years earlier, the improvement is immense. In such structural elements as the development of the ideas, the concise and energetic flow of the music, the distribution and contrast of instrumental tone, and the balance and proportion of sound, these works are generally held to reach a pitch almost unsurpassable from the point of view of technical criticism. Mozart's intelligence and taste, dealing with thoughts as yet undisturbed by strong or passionate emotion, attained a degree of perfection in the sense of pure and directly intelligible art which later times can scarcely hope to see approached.

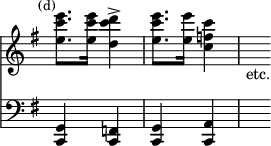

Haydn's symphonies up to this time cannot be said to equal Mozart's in any respect; though they show a considerable improvement on the style of treatment and expression in the 'Trauer' or the 'Farewell' Symphonies. Of those which are better known of about this date are 'La Poule' and 'Letter V,' which were written (both for Paris) in 1786 and 1787. 'Letter Q,' or the 'Oxford' Symphony, which was performed when Haydn received the degree of Doctor of Music from that university, dates from 1788, the same year as Mozart's great triad. 'Letter V and 'Letter Q' are in his mature style, and thoroughly characteristic in every respect. The orchestration is clear and fresh, though not so sympathetic nor so elastic in its variety as Mozart's; and the ideas, with all their geniality and directness, are not up to his own highest standard. It is the last twelve, which were written for Salomon after 1790, which have really fixed Haydn's high position as a composer of symphonies; these became so popular as practically to supersede the numerous works of all his predecessors and contemporaries except Mozart, to the extent of causing them to be almost completely forgotten. This is owing partly to the high pitch of technical skill which he attained, partly to the freshness and geniality of his ideas, and partly to the vigour and daring of harmonic progression which he manifested. He and Mozart together enriched this branch of art to an extraordinary degree, and towards the end of their lives began to introduce far deeper feeling and earnestness into the style than had been customary in early works of the class. The average orchestra had increased in size, and at the same time had gained a better balance of its component elements. Instead of the customary little group of strings and four wind instruments, it had come to comprise, besides the strings, 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, and drums. To these were occasionally added 2 clarinets, as in Haydn's three last (the two in D minor and one in E♭), and in one movement of the Military Symphony. Neither Mozart nor Haydn ever used trombones in symphonies; but uncommon instruments were sometimes employed, as in the 'Military,' in which Haydn used a big drum, a triangle and cymbals. In his latest symphonies Haydn's treatment of his orchestra agrees in general with the description already given of Mozart's. The bass has attained a free motion of its own; the violas rarely cling in a dependent manner to it, but have their own individual work to do, and the same applies to the second violins, which no longer so often appear merely 'col 1mo.' The wind instruments fill up and sustain the harmonies as completely as in former days; but they cease merely to hold long notes without characteristic features, or slavishly to follow the string parts whenever something livelier is required. They may still play a great deal that is mere doubling, but there is generally method in it; and the musical ideas they express are in a great measure proportioned to their characters and style of utterance. Haydn was rather fond of long passages for wind alone, as in the slow movement of the Oxford Symphony, the opening passage of the first allegro of the Military Symphony, and the 'working out' of the Symphony in C, no. 1 of the Salomon set. Solos in a tune-form for wind instruments are also rather more common than in Mozart's works, and in many respects the various elements which go to make up the whole are less assimilated than they are by Mozart. The tunes are generally more definite in their outlines, and stand in less close relation with their context. It appears as if Haydn always retained to the last a strong sympathy with simple people's-tunes; the character of his minuets and trios, and especially of his finales, is sometimes strongly defined in this respect; but his way of expressing them within the limits he chose is extraordinarily finished and acute. It is possible that, as before suggested, he got his taste for surprises in harmonic progression from C. P. E. Bach. His instinct for such things, considering the age he lived in, was very remarkable. The passage on the next page, from his Symphony in C, just referred to, illustrates several of the above points at once.

The period of Haydn and Mozart is in every respect the principal crisis in the history of the Symphony. When they came upon the scene, it was not regarded as a very important form of art. In the good musical centres of those times—and there were many—there was a great demand for symphonies; but the bands for which they were written were small, and appear from the most natural inferences not to have been very efficient or well organised. The standard of performance was evidently rough, and composers could neither expect much attention to pianos and fortes, nor any ability to grapple with technical difficulties among the players of bass instruments or violas. The audiences were critical in the one sense of requiring good healthy workmanship in the writing of the pieces—in fact much better than they would demand in the present day; but with regard to deep meaning, refinement, poetical intention, or originality, they

appear to have cared very little. They wanted to be healthily pleased and entertained, not stirred with deep emotion; and the purposes of composers in those days were consequently not exalted to any high pitch, but were limited to a simple and unpretentious supply, in accordance with demand and opportunity. Haydn was influenced by these considerations till the last. There is always more fun and gaiety in his music than pensiveness or serious reflection. But in developing the technical part of expression, in proportioning the means to the end, and in organising the forces of the orchestra, what he did was of the utmost importance. It is, however, impossible to apportion the value of the work of the two masters. Haydn did a great deal of important and substantial work before Mozart came into prominence in the same field. But after the first great mark had been made by the Paris Symphony, Mozart seemed to rush to his culmination; and in the last four of his works reached a style which appears richer, more sympathetic, and more complete than anything Haydn could attain to. Then, again, when he had passed away, Haydn produced his greatest works. Each composer had his distinctive characteristics, and each is delightful in his own way; but Haydn would probably not have reached his highest development without the influence of his more richly gifted contemporary; and Mozart for his part was undoubtedly very much under the influence of Haydn at an important part of his career. The best that can be said by way of distinguishing their respective shares in the result is that Mozart's last symphonies introduced an intrinsically musical element which had before been wanting, and showed a supreme perfection of actual art in their structure; while Haydn in the long series of his works cultivated and refined his own powers to such an extent that when his last symphonies had made their appearance, the status of the symphony was raised beyond the possibility of a return to the old level. In fact he gave this branch of art a stability and breadth which served as the basis upon which the art of succeeding generations appears to rest; and the simplicity and clearness of his style and structural principles supplied an intelligible model for his successors to follow.

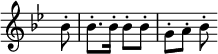

One of the most important of the contemporaries of Haydn and Mozart in this department of art was F. J. Gossec. He was born in 1733, one year after Haydn, and lived like him to a good old age. His chief claim to remembrance is the good work which he did in improving the standard of taste for instrumental music in France. According to Fétis such things as instrumental symphonies were absolutely unknown in Paris before 1754, in which year Gossec published his first, five years before Haydn's first attempt. Gossec's work was carried on most effectually by his founding, in 1770, the 'Concert des Amateurs,' for whom he wrote his most important works. He also took the management of the famous Concerts Spirituels, with Gaviniés and Leduc, in 1773, and furthered the cause of good instrumental music there as well. The few symphonies of his to be found in this country are of the same calibre, and for the same groups of instruments as those of J. C. Bach, Abel, etc., already described; but Fétis attributes importance to him chiefly because of the way in which he extended the dimensions and resources of the orchestra. His Symphony in D, no. 21, written soon after the founding of the Concert des Amateurs, was for a full set of strings, flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and drums; and this was doubtless an astonishing force to the Parisians, accustomed as they had been to regard the compositions of Lulli and Rameau as the best specimens of instrumental music. But it is clear from other indications that Gossec had considerable ideas about the ways in which instrumental music might be improved, analogous on a much smaller scale to the aspirations and attempts of Berlioz at a later date. Not only are his works carefully marked with pianos and fortes, but in some (as the Symphonies of op. xii.) there are elaborate directions as to how the movements are to be played. Some of these are curious. For instance, over the 1st violin part of the slow movement of the second symphony is printed the following: 'La différence du Fort au Doux dans ce morceau doit être excessive, et le mouvement modéré, à l'aise, qu'il semble se jouer avec le plus grand facilité.' Nearly all the separate movements of this set have some such directions, either longer or shorter; the inference from which is that Gossec had a strong idea of expression and style in performance, and did not find his bands very easily led in these respects. The movements themselves are on the same small scale as those of J. C. Bach, Abel, and Stamitz; and very rarely have the double bar and repeat in the first movements, though these often make their appearance in the finales. The style is to a certain extent individual; not so robust or so full as that of Bach or Stamitz, but not without attractiveness. As his works are very difficult to get sight of, the following quotation from the last movement of a symphony in B♭ will serve to give some idea of his style and manner of scoring.

![{ << \new Staff << \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 2/4 \tempo "Allegro ballabile." \key bes \major

\new Voice \relative f'' { \stemUp

f4.^\markup \small \right-align "Oboi" ees8 |

d16 c bes a bes8 \grace a'16 g f | f4. ees8 |

d16 c bes a bes8 \grace a'16 g f | %end line 1

f4. aes16 g | g8 bes16 a! a8 c16 bes | bes4 r }

\new Voice \relative f'' { \stemDown

f4. ees8 | d16 c bes a bes8 \grace { \stemDown a'16 } g f |

f4. ees8 | d16 c bes a bes8 g'16 f | %end line 1

f4. aes16 g | g8 bes16 a a8 c16 bes | bes4 s_"etc." } >>

\new Staff <<

\new Voice \relative d'' { \stemUp

d2^\markup \small \center-align "Corni in E♭" ^~ |

d ^~ d ^~ d ^~ d4 r | R2 R }

\new Voice \relative d'' { \stemDown

d2 _~ d _~ d _~ d _~ | d4 s } >>

\new Staff \relative f'' { \key bes \major

<f bes d,>4.^\markup \small \center-align "Violino 1 & 2" ees8 |

d ees16 a, bes8 \grace a'16 g f |

f4. ees8 | d ees16 a, bes8 \grace a'16 g f | %end line 1

f4. aes16 g | g8 bes16 a a8 c16 bes |

\grace c8 bes16 a bes c d8 f, }

\new Staff \relative f' { \clef alto \key bes \major

f2:16^\markup \small \right-align "Viola" f: f: f: | %eol1

f8 ees d bes' ~ | bes c4 d8 ~ | d d4 d8_"etc." }

\new Staff \relative b { \clef bass \key bes \major

bes8[^\markup \small \center-align "Cello e Basso" c d a] |

bes[ c d ees] | d[ c d a] | bes,[ c d ees] | %eol1

d[ c d bes] | ees4 f | g f } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/8/s8mj3f7rutt2yi0xgde3iozh3da3q0n/s8mj3f7r.png)

Another composer of symphonies, who is often heard of in juxtaposition with Haydn and Mozart, and sometimes as being preferred to them by the audiences of the time, is Gyrowetz. His symphonies appear to be on a larger scale than those of the prior generation of composers of second rank like himself. A few of them are occasionally to be met with in collections of 'Periodical overtures,' 'symphonies,' etc., published in separate orchestral parts. One in C, scored for small orchestra, has an introductory Adagio, an Allegro of about the dimensions of Haydn's earlier first movements, with double bar in the middle; then an Andante con sordini (the latter a favourite device in central slow movements); then a Minuet and Trio, and, to end with, a Rondo in 2-4 time, Allegro non troppo. Others, in E♭ and B♭, have much the same distribution of movements, but without the introductory Adagio. The style of them is rather mild and complacent, and not approaching in any way the interest or breadth of the works of his great contemporaries; but the subjects are clear and vivacious, and the movements seem fairly developed. Other symphony writers, who had vogue and even celebrity about this time and a little later, such as Krommer (beloved by Schubert), the Rombergs, and Eberl (at one time preferred to Beethoven), require no more than passing mention. They certainly furthered the branch of art very little, and were so completely extinguished by the exceptionally great writers who came close upon one another at that time, that it is even difficult to find traces of them.