A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Passion Music

PASSION MUSIC (Lat. Cantus Passionis Domini noslri Jesu Christi; Germ. Passions Musik). The history of the Passion of our Lord has formed part of the Service for Holy Week in every part of Christendom from time immemorial: and though, no doubt, the all-important Chapters of the Gospel in which it is contained were originally read in the ordinary tone of voice, without any attempt at musical recitation, there is evidence enough to prove that the custom of singing it to a peculiar Chaunt was introduced at a very early period into the Eastern as well as into the Western Church.

S. Gregory Nazianzen, who flourished between the years 330 and 390, seems to have been the first Ecclesiastic who entertained the idea of setting forth the History of the Passion in a dramatic form. He treated it as the Greek Poets treated their Tragedies, adapting the Dialogue to a certain sort of chaunted Recitation, and interspersing it with Choruses disposed like those of Æschylus and Sophocles. It is much to be regretted that we no longer possess the Music to which this early version was sung; for a careful examination of even the smallest fragments of it would set many vexed questions at rest. But all we know is, that the Sacred Drama really was sung throughout. [See pp. 497–498 of the present volume.]

In the Western Church the oldest known 'Cantus Passionis' is a solemn Plain Chaunt Melody, the date of which it is absolutely impossible to ascertain. As there can be no doubt that it was, in the first instance, transmitted from generation to generation by tradition only, it is quite possible that it may have undergone changes in early times; but so much care was taken in the 16th century to restore it to its pristine purity, that we may fairly accept as genuine the version which, at the instance of Pope Sixtus V, Guidetti published at Rome in the year 1586, under the title of 'Cantus ecclesiasticus Passionis Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Matthæum, Marcum, Lucam, et Joannem'—S. Matthew's version being appointed for the Mass of Palm Sunday, S. Mark's for that of the Tuesday in Holy Week, S. Luke's for that of the Wednesday, and S. John's for Good Friday.

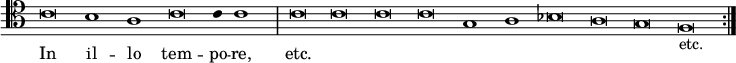

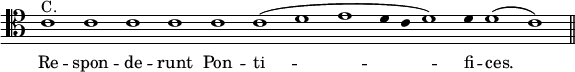

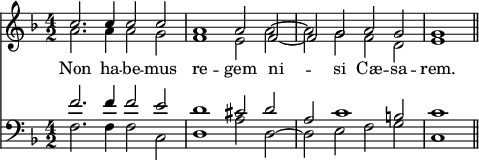

Certainly, since the beginning of the 13th century, and probably from a much earlier period, it has been the custom to sing the Music of the Passion in the following manner. The Text is divided between three Ecclesiastics called the 'Deacons of the Passion,' one of whom chaunts the words spoken by our Lord, another, the Narrative of the Evangelist, and the third, the Exclamations uttered by the Apostles, the Crowd, and others whose conversation is recorded in the Gospel. In most Missals, and other Office-Books, the part of the First Deacon is indicated by a Cross; that of the Second by the letter C. (for Chronista), and that of the Third by S. (for Synagoga). Sometimes, however, the First part is marked by the Greek letter Χ. (for Christus), the Second by E. (for Evangelista), and the Third by T. (for Turbo). Less frequent forms are, a Cross for Christus, C. for Cantor, and S. for Succentor; or S. for Salvator, E. for Evangelista, and Ch. for Chorus. Finally, we occasionally find the part of our Lord marked B. for Bassus; that of the Evangelist M. for Medius; and that of the Crowd A. for Altus; the First Deacon being always a Bass Singer, the Second a Tenor, and the Third an Alto. A different phrase of the Chaunt is allotted to each Voice; but the same phrases are repeated over and over again throughout to different words, varying only in the Cadence, which is subject to certain changes determined by the nature of the Voice which is to follow. The Second Deacon announces the History and the name of the Evangelist, thus:—

He then proceeds with the Narrative, thus:—

But, if one of the utterances of our Lord should follow, he changes the Cadence, thus:—

When the Crowd follows, he sings thus:—

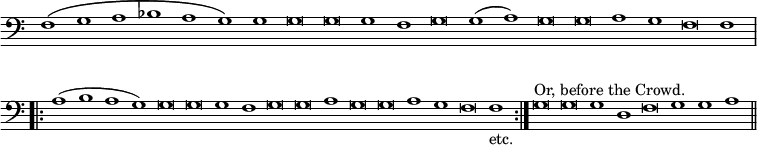

Our Lord's words are sung by the First Deacon, thus:—

Or, at a Final Close.

The Third Deacon sings thus:—

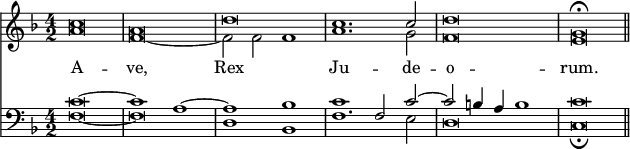

Until the latter half of the 16th century the Passion was always sung in this manner by the three Deacons alone. The difficulty of so singing it is almost incredible; but its effect, when really well chaunted, is most touching. Still, the members of the Pontifical Choir believed it possible to improve upon the time-honoured custom; and, in the year 1585, Vittoria produced a very simple polyphonic setting of those portions of the text which are uttered by the Crowd, the effect of which, intermingled with the Chaunt sung by the Deacons, was found to be so striking, that it has ever since remained in use. His wailing harmonies are written in such strict accordance with the spirit of the older Melody, that no suspicion of incongruity between them is anywhere perceptible. The several clauses fit into each other as smoothly as those of a Litany, and the general effect is so beautiful that it has been celebrated for the last three centuries as one of the greatest triumphs of Polyphonic Art.

Mendelssohn, indeed, objects to it rather fiercely in one of his Letters, on the ground that it is neither dramatic nor descriptive; that the Music does not properly express the sense of the text; and that especially the words, 'Crucifige eum,' are sung by 'very tame Jews indeed' (sehr zahme Jüden). But we must remember that there was nothing whatever in common between the purely devotional Music of the Polyphonic School and that of the 'Reformirte Kirche' to which Mendelssohn was attached So little did he sympathise with it, that, as he himself has told us, he could not even endure its constant alternation of Recitation and Cadence in an ordinary Psalm Tone. He longed for a more fiery reading of the story; and would have had its awful scenes portrayed with all the descriptive energy proper to an Oratorio. But such an exhibition as this would have been manifestly out of place in a Holy Week Service Moreover, the Evangelists themselves treat the subject in an epic and not a dramatic form; and the treatment required by the two forms is essentially different. Mendelssohn would have embodied the words, 'Crucify Him! crucify Him!' in a raging Chorus, like his own 'Stone him to death.' Vittoria sets them before us as they would have been reported by a weeping narrator, overwhelmed with sorrow at their cruelty; a narrator whose tone would have been all the more tearful in proportion to the sincerity of his affliction. Surely this is the way in which they should be sung to us in Holy Week. The object of singing the Passion is, to lead men to meditate upon it; not to divert their minds by a dramatic representation. And in this sense Vittoria has succeeded to perfection, as even the few subjoined extracts from his 'Passion according to S. John' will suffice to prove.

Francesco Suriano also brought out a polyphonic rendering of the exclamations of the Crowd, with harmonies which were certainly very beautiful, though they want the deep feeling which forms the most noticeable feature in Vittoria's settings, and, doubtless for that reason, have never attained an equal degree of celebrity. Vittoria's 'Passion' was first printed at Rome by Alessandro Gardano in 1585; and the first and last portions of it—the versions of S. Matthew and S. John—were published some years ago by R. Butler, 6 Hand Court, High Holborn, in a cheap edition which is no doubt still attainable. The entire work of Suriano will be found in Proske's 'Musica Divina,' vol. iv.

But it was not only with a view to its introduction into an Ecclesiastical Function that the Story of our Lord's Passion was set to Music. We find it in the Middle Ages selected as a constant and never-tiring theme for those Mysteries and Miracle Plays by means of which the history of the Christian Faith was disseminated among the people before they were able to read it for themselves. Some valuable reliques of the Music adapted to these antient versions of the Story are still preserved to us. An interesting example taken from a French 'Mystery of the Passion,' dating as far back as the 14th century, will be found at page 533 of the present volume. Fontenelle[1] speaks of a 'Mystery of the Passion' produced by a certain Bishop of Angers in the middle of the 15th century, with so much Music of a really dramatic character, that it might almost be described as a Lyric Drama. In this primitive work we first find the germ of an idea which Mendelssohn has used with striking effect in his Oratorio 'S.Paul.' [See Oratorio, p. 555.] After the Baptism of our Saviour, God the Father speaks; and it is recommended that His words 'should be pronounced very audibly and distinctly by three Voices at once, Treble, Alto, and Bass, all well in tune; and in this Harmony the whole Scene which follows should be sung.' Here then we have the first idea of the 'Passion Oratorio,' which however was not developed directly from it, but followed a somewhat circuitous course, adopting certain characteristics peculiar to the Mystery, together with certain others belonging to the Ecclesiastical 'Cantus Passionis' already described, and mingling these distinct though not discordant elements in such a manner as to produce eventually a form of Art, the wonderful beauty of which has rendered it immortal.

In the year 1573 a German version of the Passion was printed at Wittenberg, with Music for the Recitation and Choruses-introductory and final—in four parts. Bartholomäus Gese enlarged upon this plan, and produced, in 1588, a work in which our Lord's words are set for four Voices, those of the Crowd for five, those of S. Peter and Pontius Pilate for three, and those of the Maid Servant for two. In the next century Heinrich Schütz set to Music the several Narratives of each of the four Evangelists, making extensive use of the Melodies of the innumerable Chorales which were, at that period, more popular in Germany than any other kind of Sacred Music, and skilfully working them up into very elaborate Choruses. He did not, however, venture entirely to exclude the Ecclesiastical Plain Chaunt. In his work, as in all those that had preceded it, the venerable Melody was still retained in those portions of the narrative which were adapted to simple Recitative—or at least in those sung by the Evangelist—the Chorale being only introduced in the harmonised passages. But in 1672 Johann Sebastiani made a bolder experiment, and produced at Königsberg a 'Passion' in which the Recitatives were set entirely to original Music, and from that time forward German composers, entirely throwing off their allegiance to Ecclesiastical Tradition, struck out new paths for themselves and suffered their genius to lead them where it would.

The Teutonic idea of the 'Passions Musik' was now fully developed, and it only remained for the great Tone-Poets of the age to embody it in their own beautiful language. This they were not slow to do. Theile produced a 'Deutsche Passion' at Lübeck in 1673 (exactly a century after the publication of the celebrated German version at Wittenberg) with very great success; and, some thirty years later, Hamburg witnessed a long series of triumphs which indicated an enormous advance in the progress of Art. In 1704, Hunold Menantes wrote a Poem called 'Die Passions-Dichtung des blutigen und sterbenden Jesu,' which was set to Music by the celebrated Reinhard Reiser, then well known as the writer of many successful German Operas. The peculiarity of this work lies more in the structure of the Poem, than in that of the Music. Though it resembles the older settings in its original Recitatives and rhythmical Choruses, it differs from them in introducing, under the name of Soliloquia, an entirely new element, embodying, in a mixture of rhythmic phrase and declamatory recitation, certain pious reflections upon the progress of the Sacred Narrative. This idea, more or less exactly carried out, makes its appearance in almost every work which followed its first enunciation down to the great 'Passion Oratorios' of Joh. Seb. Bach. We find it in the Music assigned to the 'Daughter of Zion,' and the 'Chorales of the Christian Church,' in Handel's 'Passion'; in the Chorales, and many of the Airs, in Graun's 'Tod Jesu,' and in almost all the similar works of Telemann, Matheson, and other contemporary writers. Of these works, the most important were Postel's German version of the Narrative of the Passion as recorded by S. John, set to Music by Handel in 1704, and Brockes's famous Poem, 'Der für die Sünden der Welt gemarterte und sterbende Jesus,' set by Reiser in 1712, by Handel and Telemann in 1716, and by Matheson in 1718. These are all fine works, full of fervour, and abounding in new ideas and instrumental passages of great originality. They were all written in thorough earnest, and, as a natural consequence, exhibit a great advance both in construction and style. Moreover, they were all written in the true German manner, though with so much individual feeling that no trace of plagiarism is discernible in any one of them. These high qualities were thoroughly appreciated by their German auditors; and thus it was that they prepared the way, first, for the grand 'Tod Jesu,' composed by Graun at Berlin in 1755, and then for the still greater production of Sebastian Bach, whose 'Passion according to S. Matthew' is universally regarded as the finest work of the kind that ever was written.

The idea of setting the History of the Passion to the grandest possible Music, in such a manner as to combine the exact words of the Gospel-Narrative with finely developed Choruses, meditative passages like the Soliloquiæ first used by Reiser, and Chorales, sung, not by the Choir alone, but by the Choir in four-part Harmony, and by the Congregation in Unison, was first suggested to Bach by the well-known preacher Solomon Deyling. This zealous Lutheran hoped, by bringing forward such a work at Leipzig, to counteract in some measure the effect produced by the Ecclesiastical 'Cantus Passionis,' which was then sung at Dresden under the direction of Hasse, by the finest Italian Singers that could be procured. Bach entered warmly into the scheme. The Poetical portion of the work was supplied, under the direction of Deyling, by Christian Friedrich Henrici (under the pseudonym of Picander). Bach set the whole to music. And, on the evening of Good Friday, 1729, the work was performed for the first time in St. Thomas's Church, Leipzig, a Sermon being preached between the two Parts into which it is divided, in accordance with the example set by the Oratorians at the Church of S. Maria in Vallicella at Rome.

'Die grosse Passion nach Matthäus,' as it is called in Germany, is written on a gigantic scale for two complete Choirs, each accompanied by a separate Orchestra, and an Organ. Its Choruses, often written in eight real parts, are sometimes used to carry on the dramatic action in the words uttered by the Crowd, or the Apostles, and sometimes offer a commentary upon the Narrative, like the Choruses of a Greek Tragedy. In the former class of Movements, the dramatic element is occasionally brought out with telling effect, as in the reiteration of the Apostles' question, 'Lord, is it I?' The finest examples of the second class are, the introductory Double Chorus, in 12-8 Time, the fiery Movement which follows the Duet for Soprano and Alto near the end of the First Part, and the exquisitely beautiful 'Farewell' to the Crucified Saviour which concludes the whole. The part of the Evangelist is allotted to a Tenor Voice, and is carefully restricted to the narrative portion of the words. The moment any Character in the solemn Drama is made to speak in his own words, those words are committed to another Singer, even though they should involve but a single ejaculation. Almost all the Airs are formed upon the model of the Soliloquiæ already mentioned; and most of them are sung by 'The Daughter of Zion.' The Chorales are supposed to express the Voice of the whole Christian Church, and are therefore so arranged as to fall within the power of an ordinary German Congregation, to the several members of which every Tune would naturally be familiar. The style in which they are harmonised is less simple, by far, than that adopted by Graun in his 'Tod Jesu'; but as the Melodies are always sung in Germany very slowly, the Passing-notes sung by the Choir and played by the Organ serve rather to help and support the unisonous congregational part than to disturb it, and the effect produced by this mode of performance can scarcely be conceived by those who have not actually heard it.[2] The masterly treatment of these old popular Tunes undoubtedly individualises the work more stronyly than any learning or ingenuity could possibly do; but, in another point, the Matthäus-Passion stands alone above the greatest German works of the period. Its Instrumentation is, in its own peculiar style, inimitable. It is always written in real parts—frequently in very many. Yet it is made to produce endless varieties of effect. Not, indeed, in a single Movement; for most of the Movements exhibit the same treatment throughout. But the instrumental contrasts between contiguous Movements are arranged with admirable skill. Perhaps the most beautiful instance of this occurs in an Air, accompanied by two Oboi da caccia, and a Solo Flute. As, for some unexplained reason, this lovely air has been frequently omitted in performance, we subjoin a few bars as an example of Bach's delightful manner of using these expressive Instruments:—

![{ \time 3/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) <<

\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = #"voice oohs"} \relative e'' { \autoBeamOff r4^"Voice" r e | e2. ~ e16[ g f e] f[ e d c] b[ d c e] | d[ e] f4 e8 e d d[ c] c4 c8 a | f' f f f f f | f( dis) e4 r | r r r8 a, | gis b e d d cis | cis8.[ b16] cis4 c ~ | c8[ fis] dis[ c] \appoggiatura b8 a4 | a8[ gis] gis4\fermata }

\addlyrics { For love __ _ _ _ _ _ my Sa -- viour suffer -- ed, For love of us my Sa -- viour suffer -- ed, For love of us my Sa -- viour suf __ _ _ _ _ _ fered. }

\new GrandStaff <<

\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = #"flute"} \relative a'' { a8.^"Fl. solo" g32 f e16 a e d d b' d, c | c b a gis a b c d e f e g | f2. ~ | f16 c' b a b a gis fis e d b'8 ~ | b16 d, e gis, a c e g f c' f, e | d c b c \appoggiatura b8 a4 r | r8 b8 ~ b16 a g f e d e8 ~ e16 cis d f a g f e d c d8 ~ | d16 f e d b' gis f e d b cis8 ~ | cis16 b cis e a g fis e dis b c8 ~ | c16 b c dis fis gis a b c a b8 | b4\fermata r4 }

\new Staff \with {midiInstrument = #"oboe"} << \new Voice \relative c'' { \stemUp c4^"2 Oboi da caccia" a gis | c c c | c b b b b b | s2. | a4 a c | b b bes a a a | b gis gis | a a a | a a fis e r }

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemDown a4 c, e a a a | a a a gis gis gis | a8. b16 c8. <b d>16 <a c>8. <gis b>16 | a4 a a | g! g g f f f | e e e e e e | dis dis dis d_\fermata } >> >> >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/6/56t13u0ta9dol23rznl1ci20vseh9vm/56t13u0t.png)

[ W. S. R. ]

Appendix, p.744–5:

Besides the work mentioned at the end of the article, Bach wrote four other settings of the story of the Passion. The Passion according to St. John, which is now as well known in England as its grander but not more inspired companion work, was first performed in the Thomaskirche on Good Friday, April 7, 1724. These two masterpieces happily came into the hands of Emanuel Bach, and were thus preserved in their integrity; the other three works were left to Friedernann Bach, by whom they were sold for a small sum; two of them have so far entirely disappeared. Of these last, one was a setting according to St. Mark, performed on Good Friday, 1731, in the Thomaskirche, and the other seems to have been set to words by Picander, in the year 1725. The remaining one was a Passion according to St. Luke, the autograph of which is extant in the possession of Herr Joseph Hauser of Carlsruhe. There is no doubt that Bach wrote the MS. at some time between 1731 and 1734, but from internal considerations it is equally certain that it was not then newly composed. If the whole composition is ultimately proved to be genuine, it must be assigned to a very early period of Bach's career, probably to the first Weimar period; the question of its authenticity must be still regarded, however, as an open one, although there are many numbers in the work which bear evident traces of Bach's style. A great boon has been recently conferred upon lovers of music by the publication of the work in vocal score (Breitkopf & Härtel, 1886). The whole subject of the Passion settings is discussed at length in Spitta's Life of Bach, book v. chap. vii.

The four settings by Heinrich Schütz, mentioned on p. 665b have been published in Breitkopf & Härtel's complete edition of that composer's works, vol. i, and his Matthew Passion has also appeared in vocal score.[ M. ]