A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Oratorio

ORATORIO (Lat. Oratorium; Ital. Dramma sacra per Musica, Oratorio; Germ. Oratorium). A Sacred Poem, usually of a dramatic character, sung throughout by Solo Voices and Chorus, to the accompaniment of a full Orchestra, but—at least in modern times—without the assistance of Scenery, Dresses, or Action.

The dramatic instinct is so deeply implanted in the human mind, that it would be as hopeless to search for the earliest manifestation of its presence as for the origin of language. We have already endeavoured to trace back the history of the Opera to the infancy of Greek Tragedy. But, it is clear that dramatic performances must have had an incalculably earlier as well as an infinitely ruder origin than that; and equally certain that they have been used from tune immemorial as a means of inculcating moral and religious truth, and instructing the masses in historical and legendary lore which it would have been difficult to impress upon them by the mere force of verbal description. That they were so used in the Middle Ages is proved by abundant evidence. The Mysteries, Moralities, and Miracle Plays, which in the 13th and 14th centuries were so extensively popular throughout the whole of Europe, did more towards familiarising the multitude with the great events of Scripture History than could have been effected by any amount of simple narrative; and it is to these primitive performances, rude though they were, that we must look for the origin of that grand artistic creation—the noblest ever yet conceived with Music for its basis—which still serves to invest the Sacred Story with a living interest which we cannot but regard as a valuable help to the realisation of its inner meaning, and to impress upon our minds a more elevated Ideal than we could ver hope to reach without the aid of Song.

It is impossible to say when, where, or by whom, the first dramatic representation of a Scene from Holy Writ was attempted. One of the oldest examples of which we have any certain record is the 'Festum Asinorum,' celebrated at Beauvais and Sens, in the 12th century, and long remembered in connection with a famous Carol called the 'Prosa de Asino,' the Melody of which will be found at page 462a of the present volume. But it was not only in France that such representations found favour in the sight of the people. William Fitz Stephen mentions a Monk of Canterbury who wrote many Miracle-Plays during the reign of King Henry II, and died in 1191; and we know, from other sources, that an English audience was always ready to greet entertainments of this description with a hearty welcome. The Clergy also took them under their especial protection, and retained their interest in them for so long a period, that, in 1378 the Choristers of S. Paul's performed them regularly, under careful ecclesiastical superintendence. In other countries they attained an equal degree of popularity, but at a somewhat later date. In Italy, for instance, we hear of a 'Commedia Spirituale' performed for the first time at Padua in 1243, and another at Friuli in 1298; while 'Geistliche Schauspiele' first became common in Germany and Bohemia about the year 1322.

The subjects of these primitive pieces were chosen for the purpose of illustrating certain incidents selected from the history of the Old and New Testaments, the lives of celebrated Saints, or the meaning of Allegorical Conceits, intended to enforce important lessons in Religion and Morality. For instance, 'Il Conversione di S. Paolo' was sung in Rome in 1440, and 'Abram et Isaac suo Figluolo' at Florence in 1449. Traces are also found of 'Abel e Caino' (1554), 'Sansone' (1554), 'Abram et Sara' (1556), 'Il Figluolo Prodigo' (1565), an allegorical piece, called 'La Commedia Spirituale dell' Anima,' printed at Siena, without date (and not to be confounded with a very interesting work bearing a somewhat similar title, to be mentioned presently), and many different settings of the history of the Passion of our Lord. This last was always a very favourite subject; and the music adapted to it, combining some of the more prominent characteristics of Ecclesiastical Plain Chaunt with the freedom of the sæcular Chanson was certainly not wanting in solemnity. Particular care was always taken with that part of the Sacred Narrative which described the grief of Our Lady at the Crucifixion; and we find frequent instances of the 'Lamentation' of Mary, or of S. Mary Magdalene, or of The Three Maries, treated, in several different languages, in no unworthy manner. The following is from a MS. of the 14th century, formerly used at the Abbey of Origny Saint Benoit, but now preserved in the Library at S. Quentin.

Les Trois Maries.

No great improvement seems to have been made in the style of these performances after the 14th century; indeed, so many abuses crept into them that they were frequently prohibited by ecclesiastical authority. But the principle upon which they were founded still remained untouched, and the general opinion seemed to be rather in favour of their reformation than their absolute discontinuance. S. Philip Neri, the Founder of the Congregation of Oratorians, thought very highly of them as a means of instruction, and warmly encouraged the cultivation of Sacred Music of all kinds. On certain evenings in the week his Sermons were preceded and followed either by a selection of popular Hymns (see Laudi Spirituali), or by the dramatic rendering of a Scene from Scripture History, adnpted to the comprehension of an audience consisting chiefly of Roman youths of the humbler classes, the Discourses being delivered between the Acts of the Drama. As these observances were first introduced in the Oratory of S. Philip's newly-built Church of S. Maria in Vallicella, the performances themselves were commonly spoken of as Oratorios, and no long time elapsed before this term was accepted, not in Rome only, but throughout the whole of Europe, as the distinguishing title of the 'Dramma sacra per musica.'

S. Philip died in 1595, but the performances were not discontinued. The words of some of them are still extant, though unfortunately without the Music, which seems to have aimed at a style resembling that of the Madrigale Spirituale—just as in the 'Amfiparnasso' of Orazio Vecchi we find a close resemblance to that of the sæcular Madrigal. Nothing could have been more ill adapted than this for the expression of dramatic sentiment; and it seems not improbable that the promoters of the movement may themselves have been aware of this fact, for soon after the invention of the Monodic Style we meet with a notable change which at once introduces us to the First Period in the History of the true Oratorio. [See Monodia.]

While Peri and Caccini were cautiously feeling their way towards a new style of Dramatic Music in Florence, Emilio del Cavaliere, a Composer of no mean reputation, was endeavouring with equal earnestness to attain the same end in Rome. With this purpose in view he set to Music a Sacred Drama, written for him by Laura Guidiccioni, and entitled 'La Rappresentazione dell' Anima e del Corpo.' The piece was an allegorical one, complicated in structure, and of considerable pretensions; and the Music was written throughout in the then newly-invented stilo rappresentativo of which Emilio del Cavaliere claimed to be the originator. [See Opera, p. 499; Recitative.] The question of priority of invention is surrounded, in this case, with so many difficulties, that we cannot interrupt the course of our narrative for the purpose of discussing it. Suffice it to say that, by a singular coincidence, the year 1600 witnessed the first performance, in Rome, of Emilio's 'Rappresentazione' and, in Florence, of Peri's 'Euridice'—the earliest examples of the true Oratorio and the true Opera ever presented to the public. The Oratorio was produced at the Oratory of 5. Maria in Vallicella in the month of February, ten months before the appearance of 'Euridice' at Florence. Emilio del Cavaliere was then no longer living, but he had left such full directions, in his preface, as to the manner in which the work was to be performed, that no difficulty whatever lay in the way of bringing it out in exact accordance with his original intention, which included Scenes, Decorations, Action, and even Dancing on a regular Stage (in Palco). The principal characters were Il Tempo (Time), La Vita (Life), Il Mondo (the World), Il Piacere (Pleasure), L'Intelletto (the Intellect), L'Anima (the Soul), Il Corpo (the Body), two Youths, who recited the Prologue, and the Chorus. The Orchestra consisted of 1 Lira doppia, 1 Clavicembalo, 1 Chitarone, and 2 Flauti, 'o vero due tibie all' antica.' No Part is written for a Violin; but a note states that a good effect may be produced by playing one in unison with the Soprano Voices, throughout. The Orchestra was entirely hidden from view, but it was recommended that the various characters should carry musical instruments in their hands, and pretend to accompany their Voices, and to play the Ritornelli interposed between the Melodies allotted to them. A Madrigal, with full Instrumental Accompaniment, was to take the place of the Overture. The Curtain then rose, and the two Youths delivered the Prologue; after which a long Solo was sung by Time. The Body, when singing the words 'Se che hormai alma mia,' was to throw away his golden collar and the feathers from his hat. The World and Life were to be very richly dressed, but when divested of their ornaments, to appear very poor and wretched, and ultimately dead bodies. A great number of Instruments were to join in the Ritornelli. And, finally, it was directed that the Performance might be finished either with or without a Dance. 'If without,' says the stage-direction, 'the Vocal and Instrumental Parts of the last Chorus must be doubled. But should a Dance be preferred, the Verse beginning Chiostri altissimi e stellati must be sung, accompanied by stately and reverent steps. To these will succeed other grave steps and figures of a solemn character. During the ritornelli the four principal Dancers will perform a Ballet, embellished with capers (saltato con capriole) without singing. And thus, after each Verse, the steps of the Dance will always be varied, the four chief Dancers sometimes using the Gagliarde, sometimes the Canario, and sometimes the Corrente, which will do well in the Ritornelli.'

The general character of the Music—in which no distinction is made between Recitative and Air—will be readily understood from the following examples of portions of a Solo and Chorus.

![<< \new Staff { \time 4/4 \key c \major \tempo \markup { \caps Coro. } << \new Voice = "top" \relative b' { \stemUp \autoBeamOff r2 b4 b | g2 g4 g | fis2 fis\fermata | fis4 g a2 ~ a4 a2 g4 ~ | g fis g2\fermata | g2 g8 g g g | g2 fis\fermata | a2. a8 a | a4 a r8 g g g | g4. a8 a2 | g1\fermata \bar "||" }

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown \autoBeamOff s2 d4 d | d2 c4 b | d2 d | d4 e f2 ~ | f4 f2 cis4 | d2 d | d b8 b b b | cis d4 cis8 d2 | fis2. fis8 fis | fis4 fis s8 d d d | e4 g2 fis4 | d1 } >> }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "top" { Ques -- ta vi -- ta mor -- ta -- le per fug -- gir presto ha l'a -- le E con tal fret -- ta pas -- sa ch'a die -- tro i ven -- ti e le sa -- et -- te las -- sa. }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key c \major << \new Voice \relative b { \stemUp \autoBeamOff r2 b4 b | b2 a4 g | a2 a | a4 b c a8[ b] | c2 c4 g | a2 b | b d8 d d d | g,2 a | d2. d8 d | d4 d r8 g, g g | g4 g d'2 | b1 }

\new Voice \relative g { \stemDown \autoBeamOff s2 g4 g | g2 e4 e | d2 d_\fermata | d4 g f2 ~ | f4 f2 e4 | d2 g,_\fermata | g'2 g8 g g g | e2 d_\fermata | d2. d8 d | d4 d r8 b b b | c4 e d2 | g1_\fermata } >> }

\figures { < _ >\breve <_+>1 < _ >4 <6> < _ >2 < _ >2. <6+>4 <11> <10+> < _ >2 < _ >1 <6+>2 <_+> < _ >1 < _ >2 < _ >8 <13> < _ >2. <11+> } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/g/5gffntjrwbs41miabikj10giiprm5np/5gffntjr.png)

Had Emilio del Cavaliere lived to follow up his first Oratorio with others of similar character, the result of his labours could scarcely have failed to add greatly to his already high reputation, for his first attempt met with a very enthusiastic reception. Unfortunately, the most popular among his successors devoted so much attention to the development of the Opera, that for a time the Oratorio was almost forgotten; and it was not until more than twenty years after his death that it again excited sufficient interest to lead to the production of the series of works which illustrate the Second Period of our history.

The occasion which immediately led to this revival was the Canonisation of SS. Ignatius Loyola and Francis Xavier. In honour of this event Kapsberger set to music an Allegorical Drama, called 'Apotheosis, seu consecratio SS. Ignatii et Francisci Xaverii,' which was several times performed at the Collegio Romano, with magnificent scenic decorations and full dramatic action, in the year 1622. The Music of this piece, which is still extant, is miserably poor, and so much inferior, both in originality and dramatic form, to the works of Monteverde and other popular writers of the period, that it is impossible to believe it could have succeeded, had it not been for the splendour of the mise en scène with which it was accompanied. Another piece, on the same subject, entitled 'S. Ignatius Loyola,' was set to Music in the same year by

Vittorio Loreto. Neither the Poetry nor the Music of this have been preserved, but Erythræus[1] assures us that, though the former was poor, the latter was of the highest order of excellence, and that the success of the performance was unprecedented. Vittorio Loreto also set to Music 'La Pelligrina constante,' in 1647, and 'Il Sagrifizio d'Abramo,' in 1648. Besides these, mention is made of 'Il Lamento di S. Maria Vergine,' by Michelagnolo Capellini, in 1627; 'S. Alessio,' by Stefano Landi, in 1634; 'Enninio sul Giordano,' by Michel Angelo Rossi, in 1637; and numerous Oratorios by other Composers, of which, in most instances, the words only have survived, none appearing to have been held in any great amount of popular estimation. An exception must however be made in favour of the works of Domenico Mazzocchi, by far the greatest Composer of this particular period, whose 'Querimonia di S. Maria Maddelena' rivalled in popularity even the celebrated 'Lamento d'Arianna' of Monteverde. Domenico Mazzocchi, the elder of two highly talented brothers, though a learned Contrapuntist, was also an enthusiastic cultivator of the Monodic Style, and earnestly endeavoured to ennoble it in every possible way, and above all, to render it a worthy exponent of musical and dramatic expression. He it was who first made use of the well-known sign now called the 'Swell' (![]() ); and, bearing this fact in mind, we are not surprised to find in his Music a refinement of expression for which we may seek in vain among the works even of the best of his contemporaries. His Oratorio, 'Il Martirio di SS. Abbundio ed Abbundanzio,' was produced in Rome in 1631; but his fame rests chiefly upon the 'Querimonia,' which when performed at S. Maria in Vallicella, by such singers as Vittorio Loreto, Buonaventura, or Marcantonio, drew tears from all who heard it. The following extract will be sufficient to show the touchingly pathetic character of this famous composition—the best which the Second Period could boast.

); and, bearing this fact in mind, we are not surprised to find in his Music a refinement of expression for which we may seek in vain among the works even of the best of his contemporaries. His Oratorio, 'Il Martirio di SS. Abbundio ed Abbundanzio,' was produced in Rome in 1631; but his fame rests chiefly upon the 'Querimonia,' which when performed at S. Maria in Vallicella, by such singers as Vittorio Loreto, Buonaventura, or Marcantonio, drew tears from all who heard it. The following extract will be sufficient to show the touchingly pathetic character of this famous composition—the best which the Second Period could boast.

S. Maria Maddelena.

![<< \new Staff { \time 4/4 \key f \major \relative c'' { \autoBeamOff r8 c c c aes4 aes | r8 aes8 aes g g4. f8 | f4 f r8 aes bes c | des4 des r8 des8 des ees | ees4. f8 des4 des | r8 c bes a bes8. bes16 bes8 aes | aes4. g8 g4 g | ees' ees8 ees des4 des8 c | c2. ees4 | f16[ ees8.] ees16[ des8.] des16[ bes8.] c16[ des8.] | ees4 des c2 | bes1 } }

\addlyrics { Ben vuol sa -- nar -- la il Re -- den -- to -- re_il san -- gue, ma indar -- no spar -- si il pre -- ti -- o -- so ri -- o sa -- rà per lei di quel be -- a -- to san -- gue senza il do -- glio -- so hu -- mor del plan -- _ _ _ _ to mi -- o_etc. }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key f \major \relative f { f1 f f bes, bes bes | bes2 ees | ees4 c f g | aes g f ees | des c bes aes | g ees f2 | bes1 } } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/w/2wl8opc3e4eo0735cqsn8ijf6whk3zb/2wl8opc3.png)

Our Third Period introduces us to a greater Composer than any of whom we have hitherto had occasion to speak one of those representative men whose rare genius is powerful enough not only to inaugurate a new era in the annals of Art, but to leave its impress upon all time.

Giovanni Carissimi was the first Composer of the Monodic School who succeeded in investing the new style with a sufficient amount either of dignity or pathos to encourage a reasonable hope that it might one day produce results in some degree commensurate for good with the loss it occasioned by the destruction of Polyphony. Considered as Music, the united value of all the Monodic works produced within the first thirty years of the 17th century would be outweighed over and over again by one single bar of the least of Luca Marenzio's Madrigals. Except as stepping-stones to something better, they were absolutely worthless. Their only intrinsic merit was a marked advance in correctness of rhetorical expression. But this single good quality represented a power which, had it been judiciously used, would have led to changes exceeding in importance any that its inventors had dared to conceive, even in their wildest dreams. Unhappily, it was not judiciously used. Blinded by the insane spirit of Hellenism which so fatally counteracted the best effects of the Renaissance, the pioneers of the modern style strove to find a royal road to dramatic truth which would save them the trouble of studying Musical Science; and they failed, as a matter of course; for the expression they aimed at, instead of being enforced by the harmonious progression of its accompaniment, was too often destroyed by its intolerable cacophony.[2] It remained for Carissimi to prove that truth of expression and purity of harmonic relations were interdependent upon each other; that really good Music, beautiful in itself, and valuable for its own sake, was not only the fittest possible exponent of dramatic sentiment, but was rendered infinitely more beautiful by its connection therewith, and became the more valuable in exact proportion to the amount of poetical imagery with which it was enriched. Forming his style upon this sure basis, and trusting to his contrapuntal skill to enable him to carry out the principle, Carissimi wrote good Music always—Music which would have been pleasant enough to listen to for its own sake, but which became infinitely more interesting when used as a vehicle for the expression of all those tender shades of joy and sorrow which make up the sum of what is usually called 'human passion.' His refined taste and graceful manner enabled him to do this so successfully, that he soon outshone all his contemporaries, who looked upon him as a model of artistic excellence. His first efforts were devoted to the perfection of the Sacred Cantata, of which he has left us a multitude of beautiful examples; but he also wrote numerous Oratorios, among which the best known are 'Jephte,' 'Ezechias,' 'Baltazar,' 'David et Jonathas,' 'Abraham et Isaac,' 'Jonas,' 'Judicium Salomonis,' 'L'Histoire de Job,' 'La Plainte des Damne's,' 'Le Mauvais Riche,' and 'Le Jugement Dernier.' These are all full of beauties, and, in 'Jephte' especially, the Composer has reached a depth of pathos which none but the greatest of Singers can hope to interpret satisfactorily. The Solo, 'Plorate colles,' assigned to Jephtha's Daughter, is a model of tender expression; and the Echo, sung by two Sopranos, at the end of each clause of the Melody, adds an inexpressible charm to its melancholy effect.[3]

![<< \new Staff = "upper" { \time 4/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \tempo \markup { \caps Filia. } <<

\new Voice = "filia" \relative a' { \stemUp \autoBeamOff r4 r8 a c4 c8. bes16 | d[ c] c8 a2 gis4 | a4 r8 e' f4 f8 ees | g16[ f] f8 d2 cis4 | d2 fis,8 fis16 fis fis8 fis | a a a g g4 g | f f16[ g a g] e2 ~ | e4 dis e2 | b'8 b16 b b8 b d d d c | c4 c bes bes16[ c d c] | a2. gis4 | a1 | d2. d16[ e f e] | c4 b a2 \bar "||" }

\new Voice = "echo" \relative b' { \stemDown \autoBeamOff s1 s s s s s s s s s s s bes4 bes16[ c d c] a2 ~ | a4 gis a2 }

\new Voice = "accomp" \relative c' { \stemDown \tiny <c e>1 | <f bes>4 c8 d e2 | <c e>4 <cis g'> <d f>2 | <ees bes>4 f8 g <e a>2 | <d fis a>1 | <fis b,>2 <e b> | c2 s | s1 | e2 <e b'> | <e a> f | c4 d e b | c1 } >> }

\new Lyrics \with { alignAboveContext = "upper" } { \lyricsto "filia" { Plo -- ra -- te, plo -- ra -- te col -- _ les, do -- le -- te, do -- le -- te, mon -- _ tes, et in af -- flic -- ti -- o -- ne cor -- dis me -- i u -- lu -- la -- _ te, et in af -- flic -- ti -- o -- ne cor -- dis me -- i, u -- lu -- la -- _ te. U -- lu -- la -- _ te. } }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "echo" { U -- lu -- la -- _ te. }

\new Staff << \clef bass

\new Voice \relative a, { \stemDown a1 | d4 f e2 | a, d | g,4 bes a2 | d1 | dis2 e | a, c | b e, | gis1 | a2 d | f e | a,1 | d2^\markup { \caps Echo. } f | e a, }

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemUp \tiny s1 d4 a b!2 | a a | g4 d e2 | s1 s | s2 g4 a <b fis>2 ~ <b e,> } >> >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/m/qmh94grk3ccpz7ep3a8j7vmovs6e4i2/qmh94grk.png)

It was about this time that the spectacular representation began gradually to fall into disuse, though the dramatic character of the Poem was still retained, with certain modifications, chief among which was the introduction of a Personage called the 'Historicus,' to whom were assigned certain narrative passages interpolated between the clauses of the Dialogue for the purpose of carrying on the story intelligibly in the absence of scenic action. This idea was no doubt suggested by the manner of singing the History of the Passion during Holy Week in the Pontifical Chapel, where the 'First Deacon of the Passion' sings the words of Our Lord, the Second those of the Chronista (or Evangelista), and the Third those of the Synagoga (or Turba). Carissimi used this expedient freely, and his example soon led to its general adoption, both in Italy and Germany. His Oratorios indeed excited such universal admiration, that for very many years they served as models which the best Composers of the time were not ashamed to imitate. As a matter of course, they were sometimes imitated very badly; but they laid, nevertheless, the foundation of a very splendid School, of which we shall now proceed to sketch the history, under the title of our Fourth Period.

Carissimi's most illustrious disciple—the only one perhaps whose genius shone more brightly than his own—was Alessandro Scarlatti, a Composer gifted with talents so versatile that it is impossible to say whether he excelled most in the Cantata, the Oratorio, or the Opera. His Sacred Music, with which alone we are here concerned, was characterised by a breadth of style and dignity of manner which we cannot but regard as the natural consequence of his great contrapuntal skill, acquired by severe study at a time when it was popularly regarded as a very unimportant part of the training necessary to produce a good Composer. Scarlatti was wiser than his contemporaries, and carrying out Carissimi's principles to their natural conclusion, he attained so great a mastery over the technical difficulties of his Art that they served him as an ever ready means of expressing, in their most perfect forms, the inspirations of his fertile imagination. Dissatisfied with the meagre Recitative of his predecessors, he gave to the Aria a definite structure which it retained for more than a century—the well-balanced form, consisting of a first or principal strain, a second part, and a return to the original subject in the shape of the familiar Da Capo. The advantage of this symmetrical system over the amorphous type affected by the earlier Composers was so obvious, that it soon came into general use in every School in Europe, and maintained its ground, against all attempts at innovation, until the time of Gluck. It was found equally useful in the Opera and the Oratorio; and, in connection with the latter, we shall have to notice it even as late as the closing decades of the 18th century. Scarlatti used rhythmic melody of this kind for those highly impassioned Scenes which, in a spoken Drama, would have been represented by the Monologue, reserving Accompanied Recitative for those which involved more dramatic action combined with less depth of sentiment, and using Recitativo secco chiefly for the purpose of developing the course of the narrative—an arrangement which has been followed by later Composers, including even those of our own day. Thus carefully planned, his Oratorios were full of interest, whether regarded from a musical or a dramatic point of view. The most successful among them were 'I Dolori di Maria sempre Vergine' (Rom. 1693), 'Il Sagrifizio d'Abramo,' 'Il Martirio di Santa Teodosia,' and 'La Concezzione della beata Vergine'; but it is to be feared that many are lost, as very few of the Composer's innumerable works were printed. Dr. Burney found a very fine one in MS. in the Library of the Chiesa nuova at Rome, with 'an admirable Overture, in a style totally different from that of Lulli,' and a song with Trumpet obbligato. He does not mention the title of the work, but the following lovely Melody seems intended to be sung by the Blessed Virgin before the finding of our Lord in the Temple.

![<< \new Staff { \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4 \relative c'' { \autoBeamOff r4 c8 b a[ gis] a c | c[ b] r a a[ gis] r b16 e, | a8[ b] c a f[ e] f4 ~ | f8 d' b g e4 c'8 g | r bes a16[ g] a8 g4 c8 g | r bes a bes16 c g4 r8 c16 c | c8[ f,] bes a d[ gis,] a4 ~ | a8 b! c8. b16 a4 s8_"etc." } }

\addlyrics { Il mio fig -- lio o -- vè, che fa, do -- ve fia la mia gio -- ja, il mio te -- sor, Fig -- lio o -- v'è che fà, Fig -- lio che fà do -- ve stà? do -- ve fà la mia gio -- ja il mio te -- sor? }

\new Staff << \clef bass \new Voice \relative a, { \stemDown a4. b8 c b c a | \clef treble r8 <g'' b d> <f a d>4 r8 <e gis b> q <d gis b> | c4 r8 c c c c c | b b b b c c, r c' | c c c c c c, r4 | c'8 c c <c f> <c e>4 r | r8 <d f> d c <b d> q c <cis e> | d <dis fis> e <e e,> <e a,>4 s8 }

\new Voice \relative c'' { s1 s <c a>8 <gis e> a <a e> <a d,> <a c,> <a d,> q | <g d> q q q <g e> q s <g e> | <bes g> <g e> f16 e <f c'>8 e <g e> s4 | <g bes>8 <g e> f g16 a g4 s | s8 a f e gis b e, a | a4. gis8 a4 } >> >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/j/aj78h50v0c1lp1k1z4jtzjeego5af80/aj78h50v.png)

Alessandro Scarlatti died in 1735, at the age of 66. Among the most popular of his contemporaries were D. Francesco Federici, who wrote two Oratorios, 'Santa Cristina' and 'Santa Caterina de Siena, for the Congregation of Oratorians, in 1676; Carolo Pallavicini, who dedicated 'Il Trionfo della Castità' to Cardinal Otthoboni, about the year 1689; Fr. Ant. Pistocchi, whose 'S. Maria Vergine addolorata,' produced in 1698, is full of pathetic beauty; Giulio d'Alessandri, who wrote an interesting Oratorio called 'Santa Francesca Romana,' about 1690; and four very much greater writers, whose names are still mentioned with especial honour Caldara, Colonna, Leo, and Stradella. Caldara composed—chiefly at Vienna—a large collection of delightful Oratorios, most of which were adapted to the Poetry of Apostolo Zeno and Metastasio. The most successful of these were 'Tobia,' 'Assalone,' 'Giuseppe,' 'Davidde,' 'La Passione di Gesii Cristo,' 'Daniele,' 'San Pietro a Cesarea,' 'Gesu presentato al Tempio,' 'Gerusalemme convertita,' and most especially 'Sisera,' which, as Zeno himself confesses, owed its reputation entirely to the beauty of the Music. Colonna's style—especially that of his Choruses—was broader and more dignified than Caldara's, and he did much towards raising the Oratorio to the noble level it attained in the 18th century. Leo rose still higher. His Oratorio, 'Santa Elena al Calvario,' is far in advance of the age in which it was written, and contains a Chorus—'Di quanta pena è frutta—which has excited much attention. But in point of natural genius there can be no doubt that Alessandro Stradella excelled all the best writers of this promising though clearly transitional period; and our regret for his untimely death is increased by the certainty that but for this he could scarcely have failed to take a place among the greatest Composers of any age or country. There seems no reason to doubt the veracity of the tradition which represents his first and only Oratorio, 'San Giovanni Battista,' as having been the means of saving his life, by melting the hearts of the ruffians who were sent to assassinate him, on the occasion of its first performance in the Church of S. John Lateran; but whether the story be true or not, the work seems certainly beautiful enough to have produced such an effect. The most probable date assigned to it is 1676; but it differs, in many respects, from the type most in favour at that period. It opens with a Sinfonia, consisting of three short Fugal Movements, followed by a Recitative and Air for S. John. The Accompaniment to some of the Airs is most ingenious, and not a little complicated, comprising two complete Orchestras,—a Concertino, consisting of two Violins and a Violoncello, reinforced, as in Corelli's Concertos, by the two Violins, Viola, and Bass, of a Concerto grosso. These Instruments were frequently made to play in as many real parts as there were Instruments employed; but many of the Songs were accompanied only by a cleverly-constructed Ground-Bass, played con tutti i bassi del concerto grosso. Some of the Choruses, for five Voices, are very finely written, and full of contrivances no less effective than ingenious; but the great merit of the work lies in the refinement of its expression, which far exceeds that exhibited in any contemporary productions with which we are acquainted. This quality is beautifully exemplified in the following Melody, sung by the 'Consigliero.'

To this period also must be referred Handel's Italian Oratorio, 'La Resurrezione'; a composition now almost forgotten, yet deeply interesting as an historical study. We have no means now of ascertaining whether this work was ever publicly performed or not. All that can be discovered respecting it is, that it was composed in the palace of the Marchese di Ruspoli, during Handel's residence in Rome in 1708. There is no evidence to prove whether it was originally intended for representation at the Theatre, or, without action, in a Church; but the dramatic force exhibited in it from beginning to end, far exceeds in intensity anything to be found in the most advanced works of any contemporary Composer. The originality of the Air, 'Ferma l'ali,' sung by S. Maria Maddelena, in which the most tenderly pathetic effect is produced by a 'Pedal-Point' of thirty-nine bars duration is very striking; and still more so is the furious accompaniment to Lucifero's Air, 'O voi dell' Erebo potenze orribili,'—a passage which we find imitated in connection with the Enchantment of Medea, in the Third Act of 'Teseo,' written four years later.

![<< \new Staff { \clef bass \time 3/8 \key bes \major \tempo \markup { \italic { Violini all' 8va. } } \relative c { \autoBeamOff c8 ees g | c bes16[ aes] g[ f] | ees8 g bes | ees d16[ c] bes[ aes] | g16.[ aes32] bes8 c | d,16.[ ees32] f8 g | c,16.[ d32] ees8 f | g,4. | R4.*4 } }

\addlyrics { O vol dell' E -- re -- bo poten -- ze or -- ri -- bi -- li So me -- co -- ar -- ma -- te -- vi d'i -- ra e va -- te. }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key bes \major \relative c { c8^\markup { \italic { T. S. } } _\markup { \italic { Tutti Bassi unà. } } ees g | c bes16[ aes] g[ f] | ees8 g bes | ees d16[ c] bes[ aes] | g16.[ aes32] bes8 c | d,16.[ ees32] f8 g | c,16.[ d32] ees8 f | g,8 ~ g64 g a b c d ees f g a b c d ees f g \clef tenor aes8 aes aes | aes ~ aes16 g64 f ees d c b a g f ees d c \clef bass b8 b b | b4.^"etc." } } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/5/25agpw7wgvv2lyx3fj56iovho1yezgx/25agpw7w.png)

We can scarcely find a stronger proof than this of Handel's wonderful power of adapting himself to surrounding circumstances. He had already, as we shall presently see, composed a German Oratorio, full of earnest thought and devotional expression: yet here, in Italy, he gives his entire attention to dramatic effect; and so far lays aside his contrapuntal accomplishments as to introduce two little choruses only, both conceived on the smallest possible scale, and the concluding one neither more nor less than a simple Gavotte, of the kind then generally used at the close of an Opera.

1ma Volta Soprani soli. 2nda Volta, Soprani, Alti, e Tenori, all' 8va.

Up to this point the development of the Oratorio corresponded, step for step, with that of the Opera. Both were treated, by the same Composers, in very nearly the same manner; the only difference being, that the more superficial writers were incapable of rising to the sublimity of scriptural language, while the men of real genius strove to surround their several subjects with a dignity which would have been quite out of place if used to illustrate a mere mythological fable. Earnestly endeavouring to accommodate the sentiment of their Music to that of the words to which it was adapted, this latter class of writers succeeded, as we have seen, in striking out for themselves a style which was generally recognised as peculiar to the Sacred Music of Italy. But it was in Italy alone that this style prevailed. In Germany, the Oratorio started, indeed, from the Miracle Play, as its primary basis: but it travelled on quite another road to perfection; and, in treating of our Fifth Period, we shall have to take entirely new elements into consideration.

The Oratorio proper, as distinguished from the earlier Mystery, made its first appearance in Germany not long after the beginning of the 17th century. It had, indeed, been foreshadowed, even before that time, in the 'Passio secundum Matthæum,' printed at Nuremberg, in 1570, by Clemens Stephani; but this can scarcely be called an Oratorio, in the strict sense of the word. The oldest example of the true German Oratorio that has been preserved to us is 'Die Auferstehung Christi' of Heinrich Schütz, produced at Dresden in 1623; a very singular work, in which the conduct of the Sacred Narrative is committed almost entirely to a Chor des Evangelisten, and a Chor der Personen Colloquenten, the Accompaniments consisting of four Viole df gamba and Organ, concerning the arrangement of which the Composer gives very minute directions in the printed copy of the Music. This remarkable piece, though it was accompanied by no dramatic action, occupies a place in the history of German Sacred Music very nearly analogous to that which we have accorded to Emilio del Cavaliere's 'Anima e Corpo' in the annals of the Italian Oratorio. It was the first of a long line of works which all carried out, more or less closely, the leading idea it set forth for imitation. Schütz followed it up with another Oratorio, called 'Die sieben Worte Christi,' and four settings of the Passion of our Lord. To the illustration of this last-named subject the Teutonic Composers of this century dedicated the noblest efforts of their skill; presenting it sometimes in a dramatic and sometimes in an epic form, but always setting it to Music, throughout, for Solo Voices and Chorus, without the introduction of spoken dialogue, and without scenic action of any kind. A very fine example was published at Königsberg in 1672 by Johann Sebastiani; and in the following year Theile produced a 'Deutsche Passion' at Lübeck. But these tentative productions were all completely eclipsed in the year 1704 by the appearance at Hamburg of two works which at once stamped the German Oratorio as one of the grandest Art-forms then in existence. These were the 'Passions-Dichtung des blutigen und sterbenden Jesu,' written by Hunold Menantes, and set to music by Reinhard Keiser; and the 'Passion nach Cap. 19 S. Johannis,' written by Postel, and composed by Handel, in a manner so different from that which he adopted four years later in his Italian Oratorio, that, without overwhelming evidence to prove the fact, it would be impossible to believe that both works were by the same Composer. These were followed, in 1705, by Mattheson's 'Das heilsame Gebet, und die Menschwerdung Christ!'; and some years later by Brockes's Poem, 'Der für die Sünde der Welt gemartete und sterbende Jesus,' set to music by Keiser in 1714, by Handel and Telemann in 1716, and by Mattheson in 1718. The general tone of German Music was more elevated by these great works than by anything that had preceded them. That their style should be diametrically opposed to that exhibited in the Italian Oratorios of the period was only to be expected; for, though the Germans were not averse from cultivating the Monodic Style, they never abetted their Italian contemporaries in their mad rebellion against the laws of Counterpoint. The ingenious devices of Polyphony were respected in Germany, even during the first three decades of the 17th century, when Italian dramatic Composers affected to deride them as follies too childish for serious consideration; and they were not without their effect upon the national style. It is true, they had not long had an opportunity of leavening it; yet the influence of the Venetian School upon that of Nuremberg, consecrated by the life-long friendship of Giovanni Gabrieli and Hans Leo Hasler, was as lasting as it was beneficial, and. strengthened by the examples of Orlando di Lasso at Munich, and Leonard Paminger at Passau, it communicated to German Art no small portion of that solidity for which it has ever since been so deservedly famous, and which even now forms one of its most prominent characteristics. Had this influence been transmitted a century earlier, it might very well have had the effect of fusing the German and Italian Schools into one. It came too late for that. Germany could accept the Counterpoint, but felt herself independent of the Plain Chaunt Canto fermo. In place of that she substituted that form of Song which, before the close of the 16th century, had already become part of her inmost life—the national Chorale, which, absorbing into itself the still more venerable Volkslied, spoke straight to the hearts of the people throughout the length and breadth of the land. When the idea of the 'Passion Oratorio' was first conceived, the Chorale entered freely into its construction. At first it was treated with extreme simplicity—accompanied with homophonic harmonies so plain that they could only be distinguished from those intended for congregational use by the fact that the Melody was assigned to the Soprano Voice instead of to the Tenor. Its clauses were afterwards used as Fugal Subjects, or Points of Imitation, sometimes very learnedly constructed, and always exhibiting an earnestness of manner above all praise. But, however treated, the subject of the Chorale was always noble, and always introduced with a greatness of purpose far above the pettiness of national pride or bigotry. It would seem as if its cultivators had sent it into the world, in those troublous times, as a message of peace—a sort of common ground on which Catholic and Protestant might meet to contemplate the events of that awful Passion which, equally dear to both, is invested for both with exactly the same doctrinal significance. And the tradition was faithfully transmitted to another generation.

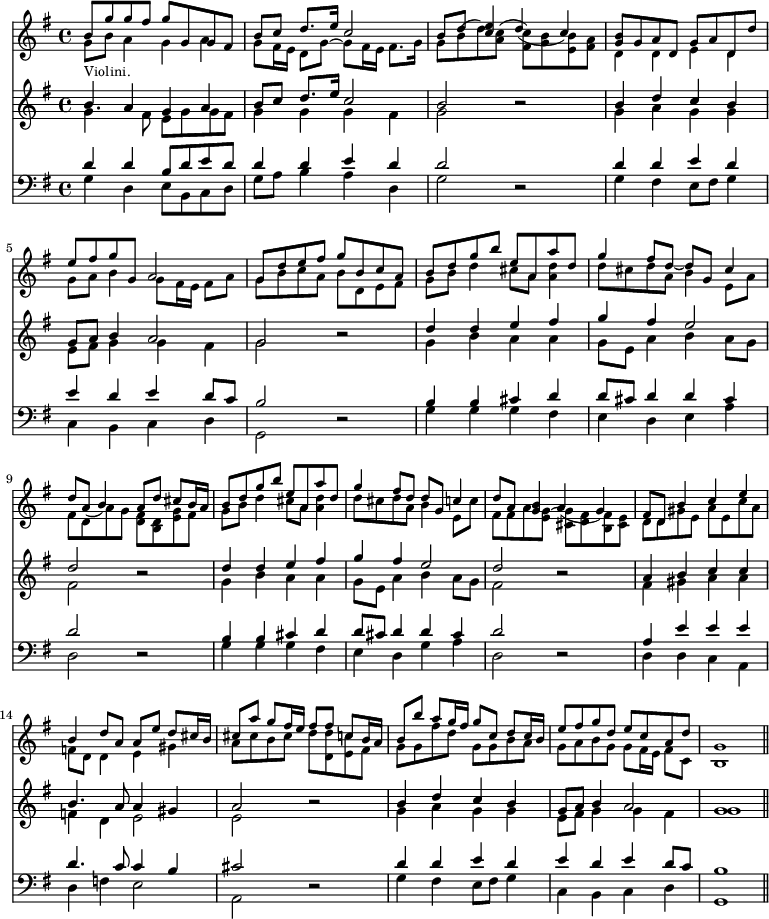

The works we have described, and many others by contemporary Musicians of good reputation, gave place in process of time to the still grander creations of the Sixth Period—creations so sublime that two Composers only can claim to be mentioned in connection with them: but those two Composers—Karl Heinrich Graun and Johann Seb. Bach—cherished the Chorale even more tenderly than their predecessors had done, and interwove it so closely into the construction of their Passion Music that it became its most prominent feature, the key-stone of the entire fabric. While still a pupil of the Kreuzschule at Dresden, and, if tradition may be trusted, before he had completed his fifteenth year, Graun wrote a 'Grosse Passions-Oratorium,' in which he introduced the melody of 'Ach wie hungert mein Gemüthe' with extraordinary effect, and in a way which no other Composer had ever previously attempted, in connection with the Institution of the Lord's Supper. His greatest work, 'Der Tod Jesu,' first produced in the Cathedral at Berlin in 1755, begins with an exquisite setting of 'O Haupt voll Blut und [4]Wunden' in homophonic harmony, and afterwards introduces five other Melodies, mostly treated in the same quiet manner, though one is skilfully combined with a Bass Solo. The Poem, by Rammler, is epic in structure, but is so arranged as to present an effective alternation of Recitatives, Airs, and Choruses. The fugal treatment of the latter is marked by a clearness of design and breadth of form which have rarely been exceeded by Composers of any age; and the whole work hangs together with a logical sequence for which one may search in vain among the Scores of ordinary writers, or indeed among the Scores of any German writers of the period, excepting Bach himself. Bach wrote three grand Oratorios, besides many of smaller dimensions which are usually classed as Cantatas. These three were 'Die Johannis-Passion' (1720); 'Die grosse Passion nach Matthäus,' first produced in the Thomas Kirche at Leipzig on Good Friday, 1729; and 'Das Weihnachts Oratorium' (1734). The Passion according to S. John is composed on a scale so much smaller than that employed for the later work according to S. Matthew, that we think it scarcely necessary to speak of both. The Text of S. Matthew's version was prepared by Christian Freidrich Henrici (under the pseudonym of Picander), and is written partly in the dramatic and partly in the epic form, with an Evangelist—the principal Tenor—who relates the various events in the wondrous History, but leaves our Lord, S. Peter, and the rest of the Dramatis personæ to use their own words, whenever the Sacred Text makes them speak in their own proper persons; a double Chorus, sometimes of Disciples, and sometimes of raging Jews, treated always in the Dramatic form; certain Airs and Choruses, called at the time they were written Soliloquies, containing Meditations on the events narrated; and a number of Chorales, in which the general Congregation was expected to join. It is impossible to say which of these different classes of Composition displays the greatest amount of genius or learning. The part of the Evangelist, and the Recitatives assigned to our Lord and His Apostles, are full of gentle dignity. The Choruses, though not fugal, abound with superb and exceedingly intricate part-writing, and are, moreover, marked by an amount of dramatic power extremely remarkable in a Composer who never gave his attention to pure dramatic Music: the last one in particular, 'Ruhet sanfte, sanfte ruh't,' is a model of touching and pathetic expression. The Airs are always accompanied in as many real parts as there are Instruments in the Score, and consequently exhibit as much contrapuntal ingenuity as the Choruses. Finally, the Chorales are treated with a depth of feeling to which Bach alone has ever attained in this peculiar style of composition. In the Christmas Oratorio, though the general conformation is very similar, the dramatic element is much less plainly brought forward. The work is divided into six portions—one for each of the first six days of the Christmas Festival; but it may quite as conveniently be divided into three for general performance. The Second Part begins with a Symphony, in 12-8 time, and of Pastoral character, second only in beauty to the 'Pastoral Symphony' in the Messiah. The Choruses are much more elaborately developed than those of the Passion, with more frequent points of Imitation, and very much less dramatic effect. But in the Chorales the treatment is exactly the same as in the two Passion Oratorios, and we cannot doubt that, in all these cases the Congregation sang the Melody, while the Chorus and Orchestra supplied the simple and wonderfully beautiful harmonies with which it is adorned. We can scarcely illustrate our remarks upon these Oratorios—the invaluable productions of the Fifth and Sixth Periods—better than by subjoining Chorales from Handel's 'Johannis Passion,' Graun's 'Tod Jesu,' and Bach's Passion according to S. Matthew.

Ei ist gewisslich an der Zeit.

Graun, 1755.

O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden.

J. S. Bach, 1729.

In the works of these great Masters the German School of Sacred Music reached its culminating point. Their successors made no attempt to compete with them on their own ground; and, before very long, the style they had so successfully cultivated yielded to the demands of fashion, and its traditions passed quite out of memory, to be revived, in our own day, with results concerning which it is not yet time to speak. But, grand as their Ideal was, it was not the grandest the Oratorio was destined to embody; nor was Germany the country fated to witness the most splendid development of that noblest of all Art-forms. Our search for it, in its highest perfection, leads us to England, where the Seventh Period of its history presents it to us under the influence of some very important modifications both of general construction and detail.

We have already seen Handel writing a true German Oratorio at Hamburg in 1704, and one after the prevailing Italian manner at Rome in 1708; but neither of these works represents the style for which he afterwards became so justly famous; nor does even the second Passion Oratorio of 1716 clearly foreshadow it, as a whole, though it may be said to do so in certain places. Not but that there are beauties enough, even in the first Passion Oratorio and the 'Resurrezione,' to pronounce him, young as he was when he wrote them, the greatest Composer of the age. We may search in vain, among contemporary productions, for evidence of such power as that displayed in 'O voi dell' Erebo potenze orribili,' or the Recitative which precedes and introduces it. But this only entitles him to rank as Primus inter pares. He had not yet perfected the stupendous conception which gave him a place, not among, but above, all other writers of the 18th century, analogous to that which Palestrina held above all those of the 16th—a position to which was attached the title, not of Primus, but of Solus. Let us endeavour to analyse this great conception; to measure the extent of the resources which rendered its embodiment possible; and to trace, as carefully as we may, the progress of its development.

When Handel wrote his first English Oratorio, 'Esther,' he was no longer an aspiring débutant, but the first Musician in Europe. Since the production of 'La Resurrezione,' he had written, for the King's Theatre in the Haymarket, five Italian Operas, two of which, 'Rinaldo' and ' Radamisto,' rank among the best he has bequeathed to us. In these, he exhibited a power of dramatic expression immeasurably exceeding anything that had ever been previously attempted. Every shade of human passion, from the tenderest pathos, through the varying phases of sorrow, anxiety, fear, terror, scorn, anger, infuriated madness, or curdling horror, may be found depicted in them, with sufficient fidelity to prove that he had the entire series absolutely at his command. This was much, to begin with; but there was more behind. Too little stress is laid, by musical critics, upon the distinction between dramatic and epic power—yet, the two forms of illustration are essentially different. Dramatic expression necessarily presupposes the presence of the Actor, who describes his own emotions in his own words. Epic power is entirely subjective. Its office is, so to act upon the hearer's imagination, as to present to him a series of pictures whether of natural scenery, of historical events, or even of dramatic scenes enacted out of sight sufficiently vivid to give him a clear idea of the situation intended to be described. Now, if in 'Deeper and deeper still' Handel has given us a convincing proof of his power as a dramatist, it is equally certain that, in the Flute Symphony to 'Augellati che Cantate' in 'Rinaldo,' the Pastoral Symphony in the 'Messiah,' and the Dead March in 'Saul,' he has shown himself no less successful as a Tone painter. The perfection of these wonderful pictures may be tested by the entire absence of the necessity for scenic accessories to give them their full force. When Mr. Sims Reeves declaims 'Deeper and deeper still,' in ordinary evening dress, he speaks as directly to our hearts, and pourtrays Jephtha's agony of soul quite as truly, as he could possibly do were he dressed in the robes of an Israelitish Judge. Before we have listened to the first three notes of the Dead March in 'Saul,' we have called up an imaginary picture of a Funeral Procession, compared with which the finest stage effect that ever machinist put together would confess itself a heap of worthless tinsel. The value lies in the Music itself; the only condition needful for its success is, that it should be well performed. In possessing the power of producing such Music, Handel was more than half prepared for the elaboration of his gigantic scheme; but one thing was still wanting—the religious element. The Scripture Narrative, considered merely as history, needed for its illustration no farther qualifications than those of which we have already spoken. But it was not enough that it should be treated merely as history; it was indispensable that its symbolical meaning should be brought out; and that that meaning should be made the turning-point of the whole. As means of effecting this, dramatic and epic expression were equally powerless; but Handel's resources were not yet at an end. Since the production of 'La Resurrezione'—in which this religious element was wholly wanting—he had written the Twelve Chandos Anthems; works now so little known that it is necessary to explain that they are not Anthems, in our present acceptation of the term, but grand Sacred Cantatas, consisting of Overtures, Solos, and Choruses, with accompaniments for a full Orchestra, and so highly developed, that many of them are quite as grand and as long as a whole Act of an Oratorio. The chief characteristic of these great works—as of the Utrecht 'Te Deum,' and 'Jubilate,' and the two settings of the 'Te Deum' for the Duke of Chandos, produced during the same period—is deep religious feeling. Not the abstract devotional feeling peculiar to true Ecclesiastical Music, like that of Palestrina. From first to last, Handel never attempted this. But, the sincere reverence of a devout mind, accompanied by a keen appreciation of the inner meaning of the text—a thorough understanding of the spirit, as well as of the letter. And here Handel's learning and ingenuity proved of incalculable advantage to him. The dignity of his grand Choruses demanded that all the subtle mysteries of Counterpoint should be brought into requisition as means of assisting their artistic development; and, of these mysteries he was thoroughly master. The smoothness of his part-writing is, indeed, little less than miraculous. However close the imitation, or complicated the involutions of the several Voices, we never meet with an inharmonious collision. He seems always to have aimed at making his parts run on velvet—whereas Bach, writing on a totally different principle, evidently delighted in bringing harmony out of discord, and made a point of introducing hard Passing-notes in order to avail himself of the pleasant effect of their ultimate resolution. Again, no other writer, either of earlier or later date, with the sole exception of Palestrina, ever possessed so great a power of concealing his learning. Carissimi, when complimented on this great quality, is reported to have said, 'Ah! questo facile, quanto é difficile!' (Ah! this ease, how difficult it is to attain!) But Carissimi never imagined the possibility of such a complication as that exhibited in the Stretto of the 'Amen Chorus'—one of the closest examples of Imitation in existence, and that creeps in so unobtrusively that the very last feeling it is likely to excite is wonder at its ingenuity.

These, then, were the resources which Handel found ready for his use, when his genius enabled him to strike out the splendid Ideal to which he owes by far the greater part of his world-wide reputation. If we examine his Oratorios, one by one, we shall find that that Ideal was susceptible of a threefold expression. It was capable of being embodied in a wholly dramatic, or a wholly epic form; or, in a form radically dramatic but relieved by frequent episodes, of an epic, a didactic, or even of a contemplative character. Though his two greatest works, 'The Messiah,' and 'Israel in Ægypt,' are purely epic, there can be no doubt that the dramatic form—without, of course, either Scenery or Action—was the one which he himself preferred; and, in carrying it out, he adhered strictly to the conditions at that time observed with regard to the technical construction of the Lyric Drama. Of the hundreds of Airs he wrote for his Oratorios, we shall not find one which cannot be referred to one or other of the well-defined classes into which the Italian Opera Airs of the 18th century were, by common consent both of Composers and Singers, invariably divided. [See Opera, pp. 509-511, vol. ii.] Thus, we see the Aria Cantabile most strikingly exemplified in 'Angels ever bright and fair'; the Aria di Portamento in 'I know that my Redeemer liveth'; the Aria di mezzo carattere in 'Waft her, Angels, through the skies'; the Aria parlante in 'He was despised'; and the Aria di bravura, in 'Rejoice greatly.' Even the minor divisions are no less clearly represented. We recognise the Cavatina in 'Sin not, O king'; the Aria d'imitazione in 'Their land brought forth frogs'; the Aria all' unisono in 'Honour and arms'; and the Aria concertata in 'Let the bright Seraphim': and it is worthy of remark that the classification is marked with equal precision, whether the examples be selected from dramatic or epic works. So far as Airs were concerned, Handel found plenty of room for his genius to assert itself within the limits defined by universal custom. But, with his Choruses, the case was very different. Here, he was absolutely free. Fashion had made no attempt to interfere with choral writing—in fact, such choral writing as his had not yet been heard. It is from him that we learn what a Chorus ought to be—and he presents it to us in an endless variety of forms. Sometimes he uses it—as it is frequently used in Greek Tragedy—as a means of drawing a lesson from some portion of the dramatic story, or moralising upon some event mentioned in the epic narrative. He has so used it in 'Envy, eldest born of Hell,' 'Is there a man?' and 'O fatal consequence of rage,' in Saul; 'The name of the wicked,' in Solomon; 'Thus, one with every virtue crowned,' in Joseph; and in innumerable other cases. Sometimes he is forcibly dramatic; as in 'Help! help the King!' in Belshazzar; or, 'We come, in bright array,' in Judas Macchabaeus. More frequently, he is descriptive, as in 'He gave them hailstones,' 'Eagles were not so swift as they,' and a hundred other instances with which the reader's memory will readily supply him. In this form of expression he never fails to produce a marvellous effect. No matter what may be the subject he undertakes to illustrate, he is always equal to it. In 'Chear her, Baal,' and 'May no rash intruder,' he soothes us with his delicious Accompaniments. In 'He sent a thick darkness,' we shudder at the awful gloom. In 'See the conquering Hero comes,' he conjures up a Scene which presents itself before us, in all its successive details, with the fidelity of a Dutch picture. But here, even when the subject is sacred, he speaks only of its earthly surroundings. When he would raise our thoughts to Heaven, he uses means which seem simple enough, when we subject them to a technical analysis, but which nevertheless possess a power which no audience can resist—the power of compelling the hearer to regard the subject from the Composer's point of view. Now, that point of view was always a sincerely devout one: and so it comes to pass that no one can scoff at the 'Messiah.' We may go to hear it in any spirit we please: but we shall come away impressed, in spite of ourselves, and confess that Handel's will, in this matter, is stronger than ours. He bids us 'Behold the Lamb of God'; and we feel that he has helped us to do so. He tells us that 'With His stripes we are healed'; and we are sensible, not of the healing only, but of the cruel price at which it was purchased. And we yield him equal obedience when he calls upon us to join him in his Hymns of Praise. Who, hearing the noble subject of 'I will sing unto the Lord' led off by the Tenors, and Altos, does not long to reinforce their voices with his own? Who does not feel a choking in his throat before the first bar of the 'Hallelujah Chorus' is completed, though he may be listening to it for the hundredth time? Hard indeed must his heart be who can refuse to hear when Handel preaches through the Voices of his Chorus. But it is not alone with voices that he speaks. The Orchestra was his slave: and by its aid he teaches us much that is worthy of our attention. It is true that we are very rarely permitted to hear what he has to say, as an instrumentalist: but, his secrets are worth finding out; and, though the subject is a vexed one, we do not intend to let it pass undiscussed.

The Orchestra, in Handel's time, consisted of a smaller Stringed Band than we are accustomed to use at the present day; but the Violins were reinforced by a greater number of Oboes, and the Basses, by a far stronger body of Bassoons. Flutes were chiefly used as Solo Instruments; but sometimes played in unison with the Oboes. The Brass Instruments were, Trumpets (doubled ad libitum), with Drums for their natural Bass; Horns; and Trombones (Alto, Tenor, and Bass), when the character of the music demanded their presence. The Harp, Viola da gamba, and other soft Instruments were occasionally used for obbligato accompaniments, in which they sometimes played an important part. The Organ was used throughout; and its part was provided for by the Figures of the Thoroughbass, which served also for the Harpsichord. With these means at his command, Handel was able to accomplish all that his fiery genius suggested; and his method of combining and contrasting the various elements of which his Band was composed may be studied with very great profit. It was his constant practice, in Airs of the cantabile class, to leave the Voice quite free from instrumental embarrassments, and supported only by the Basses, and the Chords indicated beneath the Thorough-Bass—which Chords were supplied either by the Harpsichord, or the Organ. Sometimes, the Symphonies to these Airs were played, like those usually found in the Aria di portamento, by the Violins in unison, which, thus used, between the vocal phrases, produced double their ordinary effect. In the grander Airs, the Accompaniments were much more elaborate, and served to contrast these pieces strongly with those of the former class. In the Choruses, though the entire Band was brought into constant requisition, there were often long and highly complicated passages accompanied solely by the Organ and the Basses; and, in cases of this description, the introduction of the Violins, at certain important points, produced a very striking effect—as in the 'Amen Chorus' of the 'Messiah'—not unlike that to which we have already alluded in speaking of the Symphonies of the Aria cantabile. When the Trumpets and Drums were introduced, it was always with electrical effect. Handel never wrote unnecessary notes for these wonder-working Instruments, for the mere sake of keeping them going; but took care that their silvery tone should sustain its due part in the fulfilment of his preconceived intention—a task to which they always proved themselves equal. The great strength of these arrangements lay in the perfect balance of the whole. From the beginning to the end of the work, each of its several subdivisions was exactly proportioned to all the rest. Yet, there was no lack of variety. Taking the Thorough-Bass with its accompanying chords as the lowest attainable point in the scale of effect, and the Full Band, with the Trumpets and Drums, as the highest, there lay, between these two extremes, an infinity of diverse shades, as countless as the half-tones in Turner's summer skies, all of which we find turned to good account, and so arranged as to play into each other, and contrast together, with the happiest possible influence upon the general design. But, unhappily, the delicate gradations they once represented are now rendered altogether indistinguishable by the introduction of Clarinets, Trombones, Ophicleides, Bombardons, Euphoniums, and the loud unmitigated crash of a full Military Band—an innovation quite fatal to the Composer's original intention, inasmuch as it entirely destroys the unity of purpose he so carefully endeavoured to express. An English critic—by no means a revolutionary one—in describing the Autograph Copy of the 'Messiah,' speaks in a slighting tone of 'For unto us a Child is born,' as 'meagrely scored for voices and a stringed quartet.' Handel's 'meagre score,' by accompanying the softer parts only with the Organ and Basses, and delaying the entrance of the rest of the Orchestra until the forte at the word 'Wonderful,' provides for the finest effect the Chorus can be made to produce, and furnishes us with an infinitely grander reading than that which, by its excessive contrast between pppp and ffff, borders rather upon the extravagant than the sublime. It is not too much to say that 'For unto us a Child is born' is utterly ruined by the liberties which are taken with it in performance. In other Choruses we hear a Fugal Point taken up, over and over again, by Bass Trombones, or Euphoniums, with such rousing vigour that the Voice part is rendered completely inaudible: and, in cases like this, the result is, not a richness, but a thinness of effect quite unworthy of the Composer's meaning. We are quite alive to the beauty of Mozart's Instrumentation, which has certainly never been equalled in more modern times: but, would it be sacrilege to say that even he has not risen to the level of the 'Messiah'? We must feel that there is something wanting, when we listen to his exquisite description of 'The people that walked' not 'in darkness,' but in a golden twilight so enchantingly beautiful that the 'great light' afterwards mentioned rather tends to diminish than to add to its ineffable charms. Only, let it be clearly understood that Mozart by no means satisfies the taste of the present day. When we hear of the 'Messiah,' with his 'Additional Accompaniments,' we are to understand the farther 'addition' of a complete Military Band; and the aggregate result does not leave us much margin for the criticism of Handel's original idea. Great as this evil is, it is still on the increase. Let us hope that the rapidity of its advance may the sooner provoke a reaction; and that some of us may yet live to hear the 'Messiah' sung in accordance with its author's intention.

Handel wrote, altogether, seventeen English Oratorios, beside a number of sæcular works which are sometimes incorrectly classed with them. 'Esther,' the first of the series, was first performed in the private Chapel of the Duke of Chandos, at Cannons, on August 29, 1720. That the Duke fully appreciated its significance as a Work of Art is proved by the fact that he presented the Composer with £1000 in exchange for the Score: yet, after three or four private performances it was unaccountably laid aside; and we hear no more of it for eleven years. In 1731 it was revived by the Children of the King's Chapel, who represented it, in action, at the house of their preceptor, Mr. Bernard Gates, in James Street, Westminster, and again, at a subscription concert, at the 'Crown and Anchor.' These performances were, in a certain sense, private. But, in 1732, the Oratorio was publicly performed, without the Composer's consent, at the Great Room, in Villars Street, York Buildings, under the management of a speculator who is believed to have been identified as the father of Dr. Arne. This act of piracy provoked Handel into bringing out the Oratorio himself at the King's Theatre in the Haymarket, where it was performed, 'by his Majesty's command,' without dramatic action, on May 2 in the same year. The success of this experiment fully justified the preparation of a second work of similar character, which was produced on April 2, 1733, under the title of 'Deborah.' A careful comparison of the two Oratorios furnishes us with a valuable means of measuring the progress of the Composer's Art-life, at a very eventful period. As the 'Esther' of 1720, though enriched by several important additions before its reproduction in 1732, was not actually re-written, it may be accepted as a fair representative of its author's ideas at the time it first saw the light. 'Deborah' represents the enlargement of these ideas, after thirteen years of uninterrupted study and experience. The amount of advancement indicated is very great; great enough to remind us of that observable between Beethoven's Symphony in D, and the 'Eroica'; only that we see no sign of a change of style; no change of any kind, save that the old style has grown immeasurably grander. The Overture to 'Esther' has always been more generally appreciated than that to 'Deborah,' not from any real or fancied superiority, but solely by reason of its long-continued repetition, at S. Paul's Cathedral, for the benefit of the 'Sons of the Clergy.' But, the magnificent Double Chorus with which the latter Oratorio opens so far excels anything to be found in 'Esther' that farther comparison is needless. Handel himself has rarely reached a higher standard than in 'Immortal Lord of earth and skies'; which, in fixity of purpose, breadth of design, and massive grandeur of effect, may well be ranked with some of the finest passages in 'Solomon,' or even 'Israel in Ægypt: and it is enough to say that the promise given in this glorious beginning is amply fulfilled in the Second and Third Acts. In the first Act of 'Athaliah'—produced in the Theatre at Oxford on July 10 in the same year (1733)—this massive style is wisely modified, to some extent, in order to depict the voluptuous surroundings of the Baal-worshipping Queen: but when Joash and the Hebrew Priesthood make their appearance, in the Second Act, it is resumed with all its original force. A large quantity of Music selected from this Oratorio was introduced by Handel into a Serenata, called 'Parnasso in Festa,' which was prepared in haste for the marriage of the Princess Royal, and performed before the King and the whole of the Royal Family on March 13, 1734. After this we hear of no more Sacred Music till 1739, in which year 'Saul' was produced on January 16, and 'Israel in Ægypt on April 4.[6] In force of dramatic expression, 'Saul' certainly surpasses even the finest Scenes presented in either of the three earlier works. The Song of Triumph in the First Act, with its picturesque Carillon accompaniment, marking out each successive stage in the Procession, while the jealous Monarch bursts with envy; the wailing notes of the Oboes and Bassoons in the Witch's Incantation; the gloomy pomp of the terrible 'Dead March,' and the tender pathos of David's own personal sorrow, so clearly distinguished from that felt by the Nation at large; these, and a hundred other noticeable features, would stamp 'Saul' as one of the finest dramatic works we possess, even were it shorn of its splendid Choruses, its fiery Instrumental Symphonies, and its Movements for Organ Obbligato, designed for the Composer's own interpretation. In 'Israel in Ægypt,' on the other hand, Handel first showed his power of treating a purely Epic Poem. There is every reason to believe that the Composer arranged the Text of this Oratorio for himself. At any rate, it is certain, from his method of dealing with it, that he highly approved of the arrangement, and no doubt chose the epic form from conviction of its perfect adaptability to his purpose; illustrating it—now that the dramatic element would have been clearly out of place—with Music, for the most part of a boldly descriptive character; never descending to the picturesqueness of detail which we have before had occasion to notice, yet never leaving untold anything that was necessary to the intelligent rendering of the whole. Except in describing the 'Plague of Flies,' and in a few other instances, his intention seems to have been to speak not to the outward but to the inward sense. Not to present the Scenes mentioned in the Text by means of vividly painted pictures, but to produce in the mind feelings analogous to those which, it is to be presumed, would have been produced by the contemplation of the Scenes themselves. It is enough that we are made to feel the horror of the 'Thick darkness,' and the might of the crashing 'Hailstones,' without seeing them. If we have been made to rejoice, with the Israelites, on hearing that 'The Horse and his Rider' have been 'thrown into the sea,' we need no galloping triplets to portray their headlong flight. Any other mode of treatment than this would have been beneath the dignity of the Scripture Narrative, the stupendous character of which demanded, for each several Miracle, a choral structure of such colossal proportions as had never previously been attempted. Some of the Movements in the Second Part—which was composed before the First—have been adapted from a 'Magnificat,' the Score of which, in Handel's handwriting, is preserved in the Royal Library at Buckingham Palace. This is not the place to discuss the authenticity of the MS. concerning which Dr. Chrysander holds one opinion, and Professor Macfarren and M. Schoelcher another [see Erba]; but we do not think that any unprejudiced critic after carefully studying this Oratorio, can come to the conclusion that a single note of it betrays the touch of an inferior hand. It is scarcely too much to say that unity of design is the first characteristic we look for in a really great work; and unity of design is evidently the one thing which the Composer has here borne in mind, from the beginning of his work to the end. Hence it is that 'Israel in Ægypt' holds a place far above all other works of its own peculiar kind that ever have been, or are ever likely to be written. But this peculiar form of Epic is not the only one possible. There are other feelings to be excited in the human mind besides those of awe, and horror, and wild thanksgiving for a great and unexpected Deliverance. And with some of these Handel has dealt, as no other Composer could have dealt with them, in the next great work which falls under our notice.