A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Shake

SHAKE or TRILL (Fr. Trille, formerly Tremblement, Cadence; Ger. Triller; Ital. Trillo). The shake, one of the earliest in use among the ancient graces, is also the chief and most frequent ornament of modern music, both vocal and instrumental. It consists of the regular and rapid alternation of a given note with the note above, such alternation continuing for the full duration of the written note.

The shake is the head of a family of ornaments, all founded on the alternation of a principal note with a subsidiary note one degree either above or below it, and comprising the Mordent and Pralltriller [see Mordent] still in use, and the Ribattuta (Ger. Zurückschlag) and Battement[1] (Ex. 1), both of which are now obsolete.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \tempo "1." \cadenzaOn

s4 b'32[^\markup \italic "Battement." c'' b' c'' b' c'' b'] c''2 \bar "|" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/i/c/icgtkejgveix9iwznd3hh7m03hbc9ax/icgtkejg.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \cadenzaOn \relative c'' { s4 c4.^\markup \italic "Ribattuta." d8 c8.[ d16 c8. d16] c16.[ d32 c16. d32] c16[ d16 c16 d16] s4_"etc." \bar "|" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/r/tryjceohlbt5qom8q6wtvtzqwpc0c6e/tryjceoh.png)

The sign of the shake is in modern music tr. (generally followed by a waved line ![]() if over a long note), and in older music tr.

if over a long note), and in older music tr. ![]() ,

, ![]() , and occasionally +, placed over or under the note; and it is rendered in two different ways, beginning with either the principal or the upper note, as in example 2:—

, and occasionally +, placed over or under the note; and it is rendered in two different ways, beginning with either the principal or the upper note, as in example 2:—

These two modes of performance differ considerably in effect, because the accent, which is always perceptible, however slight it may be, is given in the one case to the principal and in the other to the subsidiary note, and it is therefore important to ascertain which of the two methods should be adopted in any given case. The question has been discussed with much fervour by various writers, and the conclusions arrived at have usually taken the form of a fixed adherence to one or other of the two modes, even in apparently unsuitable cases. Most of the earlier masters, including Emanuel Bach, Marpurg, Türk, etc., held that all trills should begin with the upper note, while Hummel, Czerny, Moscheles, and modern teachers generally (with some exceptions) have preferred to begin on the principal note. This diversity of opinion indicates two different views of the very nature and meaning of the shake; according to the latter, it is a trembling or pulsation—the reiteration of the principal note, though subject to continual momentary interruptions from the subsidiary note, gives a certain undulating effect not unlike that of the tremulant of the organ; according to the former, the shake is derived from the still older appoggiatura, and consists of a series of appoggiaturas with their resolutions—is in fact a kind of elaborated appoggiatura,—and as such requires the accent to fall upon the upper or subsidiary note. This view is enforced by most of the earlier authorities; thus Marpurg says, 'the trill derives its origin from an appoggiatura (Vorschlag von oben) and is in fact a series of descending appoggiaturas executed with the greatest rapidity.' And Emanuel Bach, speaking of the employment of the shake in ancient (German) music, says 'formerly the trill was usually only introduced after an appoggiatura,' and he gives the following example—

Nevertheless, the theory which derives the shake from a trembling or pulsation, and therefore places the accent on the principal note, in which manner most shakes in modern music are executed, has the advantage of considerable, if not the highest antiquity.[2] For Caccini, in his Singing School (published 1601), describes the trillo as taught by him to his pupils, and says that it consists of the rapid repetition of a single note, and that in learning to execute it the singer must begin with a crotchet and strike each note afresh upon the vowel a (ribattere ciascuna nota con la gola, sopra la vocale a). Curiously enough he also mentions another grace which he calls Gruppo, which closely resembles the modern shake.

![{ \mark "4." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative a' { \cadenzaOn \override Staff.NoteHead.style = #'baroque

a4^\markup \italic "Trillo." a a8[ a] a16[ a] a32[ a a a] a\breve } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/4/m4fo3zvy0tp159yaufxz13puqxlodeg/m4fo3zvy.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative f' { \cadenzaOn \override Staff.NoteHead.style = #'baroque

fis4^\markup \italic "Gruppo." g16[ fis g fis] g32[ fis g fis g fis g fis] g[ fis g fis g fis g fis] g\breve } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/m/qmdsjm5nq3200nilciely926z6ki0z7/qmdsjm5n.png)

And Playford, in his 'Introduction to the Skill of Musick' (1655) quotes an anonymous treatise on 'the Italian manner of singing,' in which precisely the same two graces are described.[3] Commenting on the shake Playford says, 'I have heard of some that have attained it after this manner, in singing a plain-song of six notes up and six down, they have in the midst of every note beat or shaked with their finger upon their throat, which by often practice came to do the same notes exactly without.' It seems then clear that the original intention of a shake was to produce a trembling effect, and so the modern custom of beginning with the principal note may beheld justified.

In performing the works of the great masters from the time of Bach to Beethoven then, it should be understood that, according to the rule laid down by contemporary teachers, the shake begins with the upper or subsidiary note, but it would not be safe to conclude that this rule is to be invariably followed. In some cases we find the opposite effect definitely indicated by a small note placed before the principal note of the shake, and on the same line or space, thus—

Mozart (ascribed to), 'Une fièvre,' Var. 3.

and even when there is no small note it is no doubt correct to perform all shakes which are situated like those of the above example in the same manner, that is, beginning with the principal note. So therefore a shake at the commencement of a phrase or after a rest (Ex. 6), or after a downward leap (Ex. 7), or when preceded by a note one degree below it (Ex. 8), should begin on the principal note.

Bach, Prelude No. 16, Vol. i.

Mozart, Concerto in B♭

![{ \tempo \markup \italic "Andante" \key ees \major \time 3/8 \relative a' {

r16*1/2 aes8[ g8. c16*1/2] |

ees,8.[ d64 ees f ees] d16 r | c'4.\trill } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/y/sy7subp71jsrrfi75ai6nis5q2g3nt2/sy7subp7.png)

Bach, Art of Fugue, No. 8

Bach, Sonata for PF. and Flute, No. 6.

It is also customary to begin with the principal note when the note bearing the shake is preceded by a note one degree above it (Ex. 9), especially if the tempo be quick (Ex. 10), in which case the trill resembles the Pralltriller or inverted mordent, the only difference being that the three notes of which it is composed are of equal length, instead of the last being the longest (see vol. ii, p. 364).

Bach, Organ Fugue in F.

Mozart, Sonata in F.

If however the note preceding the shake is slurred to it (Ex. 11a), or if the trill note is preceded by an appoggiatura (Ex. 11b), the trill begins with the upper note; and this upper note is tied to the preceding note, thus delaying the entrance of the shake in a manner precisely similar to the 'bound Pralltriller' (see vol. ii. p. 364, Ex. 13). A trill so situated is called in German der gebundene Triller (the bound trill).

Bach, Concerto for two Pianos.

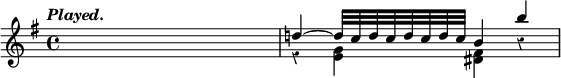

![{ \tempo \markup \italic "Played." \time 12/8 \key ees \major \relative e'' { \override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f

\hideNotes e4. e \unHideNotes ees4. ~ \tuplet 6/4 8 { ees32^([ d ees d ees d] ees[ d ees d ees d]) } c8 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/e/ke7a8r9oxlmj90hn3tp3vef7uzp5rkn/ke7a8r9o.png)

Haydn, Trio in E minor.

When the note carrying a shake is preceded by a short note of the same name (Ex. 12), the upper note always begins, unless the anticipating note is marked staccato (Ex. 13), in which case the shake begins with the principal note.

Bach, Chromatic Fantasia

![{ \tempo \markup \italic "Played." \key f \major \time 4/4 \relative b' {

<bes f d>4 ~ bes32\noBeam bes[ c d] ees64[ d ees d ees d c d] ees16[ a,32 bes] c64[ bes c bes c bes a bes] c16 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/6/f6h86qdav1mtgv8pu5oadnqhbv8ux1p/f6h86qda.png)

Mozart, Sonata in C minor

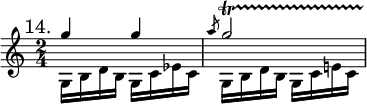

![{ \mark "13." \key c \minor \time 2/2 \relative e'' {

ees8-![ ees-!] ees\trill d16 ees f8-![ f-!] f\trill ees16 f \bar "||"

ees8-![^\markup \italic "Played." ees-!] \tuplet 3/2 { ees16[ f ees } d ees] f-![ f-!] \tuplet 3/2 { f16[ g f } ees f] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/3/43kf6ox2geq34yemozr6qrwamtjhe4r/43kf6ox2.png)

In modern music, when a trill beginning with the subsidiary note is required, it is usually indicated by a small grace-note, written immediately before the trill-note (Ex. 14). This grace-note is occasionally met with in older music (see Clementi, Sonata in B minor), but its employment is objected to by Türk, Marpurg, and others, as liable to be confused with the real appoggiatura of the bound trill, as in Ex. 11. This objection does not hold in modern music, since the bound trill is no longer used.

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 53, Finale.

Immediately before the final note of a shake a new subsidiary note is generally introduced, situated one degree below the principal note. This and the concluding principal note together form what is called the turn of the shake, though the name is not strictly appropriate, since it properly belongs to a separate species of ornament of which the turn of a shake forms in fact the second half only.[4] [See Turn.] The turn is variously indicated, sometimes by two small grace-notes (Ex. 15), sometimes by notes of ordinary size (Ex. 16), and in old music by the signs of a vertical stroke, a small curve in a downward direction, or a regular turn, added to the ordinary sign of the trill (Ex. 17).

Clementi, Sonata in C.

![{ \mark "15." \key ees \major \time 2/4 \relative g'' {

g16[ g] g32[ bes ees g] ees,16[ ees \afterGrace f8]\trill { ees16[ f] } | ees8 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/s/nsmldmabq8rotfmdvo92ecq2m7i8j22/nsmldmab.png)

Handel, Gigue (Suite 14).

For the sake of smoothness, it is necessary that the note immediately preceding the turn should be a principal note. In the shake beginning with the upper note this is the case as a matter of course (Ex. 18), but in the modern shake an extra principal note has to be added to the couple of notes which come just before the turn, while the speed of the three is slightly quickened, thus forming a triplet (Ex. 19).

![{ \mark "18." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative d'' { \cadenzaOn

\slashedGrace e8^\markup \italic "Written" \afterGrace d2\trill { c16 d } \bar "|" c4 \bar "||" e16[^\markup \italic "Played" d e d] e[ d c d] \bar "|" c4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/g/u/gurorqmkrcgo2lqh3okalsws9npkw0g/gurorqmk.png)

![{ \mark "19." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative d'' { \cadenzaOn

\afterGrace d2\trill^\markup \italic "Written" { c16 d } \bar "|" c4 \bar "||" d16[^\markup \italic "Played" e d e] \tuplet 3/2 { d[ e d] } c[ d] \bar "|" c4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/9/d9qkpy3awbrf4jxip48as7dthlt5mes/d9qkpy3a.png)

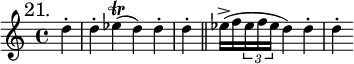

Sometimes the turn is not indicated at all, but it has nevertheless to be introduced if the shake is followed by an accented note (Ex. 20). If however the next following note is unaccented, no turn is required, but an extra principal note is added to the last couple of notes, that the trill may end as well as begin with the principal note (Ex. 21). When the trill is followed by a rest, a turn is generally made, though it is perhaps not necessary unless specially indicated (Ex. 22).

Mozart, 'Lison dormait,' Var. 8

Clementi, Sonata in G.

Beethoven, Trio, Op. 97

When a note ornamented by a shake is followed by another note of the same pitch, the lower subsidiary note only is added to the end of the shake, and the succeeding written note serves to complete the turn. This lower note is written sometimes as a small grace-note (Ex. 23), sometimes as an ordinary note (Ex. 24), and is sometimes

not written at all, but is nevertheless introduced in performance (Ex. 25).

Beethoven, Concerto in E♭

Clementi, Sonata in A.

Mozart, 'Salve tu, Domine.' Var. 4 (Cadenza).

![{ \mark "25." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative c'' { \cadenzaOn c1\trill c8.[ e16] d[ f e g] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/7/t7f7zcwrhq5l64d3i96mprmqpz79t3m/t7f7zcwr.png)

Even when the trill-note is tied to the next following, this extra lower note is required, provided the second written note is short, and occurs on an accented beat (Ex. 26). If the second note is long, the two tied notes are considered as forming one long note, and the shake is therefore continued throughout the whole value.

Bach, Fugue No. 15, Vol. 2.

![{ \new Staff << \mark "26." \key g \major \time 3/8

\new Voice \relative c'' { \stemUp c4.\trill ^~ c8 c c \bar "||"

c32[ d c d] c[ d c d] c[ d c b] | c8 c c \bar "||" }

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemDown a4. _~ a8 fis fis | a4. _~ a8 fis fis } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/0/601ym2mumkaasraup0wmur7q88k3yip/601ym2mu.png)

Very similar is the rendering of a shake on a dotted note:—the turn ends on the dot, which thus takes the place of the second of the two

notes of the same pitch. Thus the effect of the two modes of writing shown in Ex. 27 a and b, would be the same. If, however, the dotted note is followed by a note a degree lower, no turn is required (Ex. 28).

Handel, Suite 10. Allemande.

Rendering of both.

Handel, Suite 10. Allegro.

Trills on very short notes require no turn, but consist merely of a triplet—thus,

Mozart, 'Ein Weib.' Var. 6.

Besides the several modes of ending a shake, the commencement can also be varied by the addition of what is called the upper or lower prefix. The upper prefix is not met with in modern music, but occurs frequently in the works of Bach and Handel. Its sign is a tail turned upwards from the beginning of the ordinary trill mark, and its rendering is as follows—

Bach, Partita No. 1, Sarabande.

The lower prefix consists of a single lower subsidiary note prefixed to the first note of a shake which begins with the principal note, or of two notes, lower and principal, prefixed to the first note of a shake beginning with the upper note. It is indicated in various ways, by a single small grace-note (Ex. 31), by two (Ex. 32), or three grace-notes (Ex. 33), and in old music by a tail turned downwards from the commencement of the trill mark (Ex. 34), the rendering in all cases being that shown in Ex. 35.

![{ \mark "31." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 2/4 \relative c'' {

\slashedGrace b8 c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "32." \grace { b16 c } c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "33." \grace { b16 c d } c2\trill \bar "||" \mark "34." c2\upprall \bar "||" \break \mark "35." b32 c d c d[ c d c] d c d c d[ c d c] \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/1/31zz948ynsnhvd97rskgjk655la5qrb/31zz948y.png)

From a composer's habit of writing the lower prefix with one, two, or three notes, his intentions respecting the commencement of the ordinary shake without prefix, as to whether it should begin with the principal or the subsidiary note, may generally be inferred. For since it would be incorrect to render Ex. 32 or 33 in the manner shown in Ex. 36, which involves the repetition of a note, and a consequent break of legato—it follows that a composer who chooses the form Ex. 32 to express the prefix intends the shake to begin with the upper note, while the use of Ex. 33 shows that a shake beginning with the principal note is generally intended.

![{ \mark "36." \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 2/4 \relative b' { b32 c c d c[ d c d] c^"(Ex. 32.)" d c d c[ d c d] \bar "||" \break b16*2/3[ c d] d32 c d c d[^"(Ex. 33.)" c d c] d c d c } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/1/n176fddcqkyldozq0vlnq5nzwfo56vp/n176fddc.png)

That the form Ex. 31 always implies the shake beginning with the principal note is not so clear (although there is no doubt that it usually does so), for a prefix is possible which leaps from the lower to the upper subsidiary note. This exceptional form is frequently employed by Mozart, and is marked as in Ex. 37. It bears a close resemblance to the Double Appoggiatura. [See that word, vol. i. p. 79.]

Mozart, Sonata in F. Adagio.

Among modern composers, Chopin and Weber almost invariably write the prefix with two notes (Ex. 32); Beethoven uses two notes in his earlier works (see Op. 2, No. 2, Largo, bar 10), but afterwards generally one (see Op. 57).

The upper note of a shake is always the next degree of the scale above the principal note, and may therefore be either a tone or a semitone distant from it, according to its position in the scale. In the case of modulation, the shake must be made to agree with the new key, independently of the signature. Thus in the second bar of Ex. 38, the shake must be made with B♮ instead of B♭, the key having changed from C minor to C major. Sometimes such modulations are indicated by a small accidental placed close to the sign of the trill (Ex. 39).

Chopin, Ballade, Op. 67.

Beethoven, Choral Fantasia.

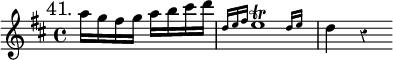

The lower subsidiary note, whether employed in the turn or as prefix, is usually a semitone distant from the principal note (Ex. 40), unless the next following written note is a whole tone below the principal note of the shake (Ex. 41). In this respect the shake follows the rules which govern the ordinary turn. [See Turn.]

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 10, No. 2.

Mozart, Rondo in D.

A series of shakes ascending or descending either diatonically or chromatically is called a Chain of Shakes (Ital. Catena di Trille; Ger. Trillerkette). Unless specially indicated, the last shake of the series is the only one which requires a turn. Where the chain ascends diatonically, as in the first bar of Ex. 42, each shake must be completed by an additional principal note at the end, but when it ascends by the chromatic alteration of a note, as from G♮ to G♯, or from A to A♯, in bar 2 of the example, the same subsidiary note serves for both principal notes, and the first of such a pair of shakes requires no extra principal note to complete it.

Beethoven, Concerto in E♭.

![{ \mark \markup \small \italic "Played." \key b \major \time 4/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative e'' {

e32 fis e fis e[ fis e fis] e fis e fis \tuplet 5/4 { e[ fis e fis e] } fis g fis g fis[ g fis g] fis g fis g \tuplet 5/4 { fis[ g fis g fis] } | g ais g ais g[ ais g ais] gis ais gis ais \tuplet 5/4 { gis[ ais gis ais gis] } s_"etc." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/x/nxhbebom9qf3jk3ht3vhkfxi81ig9km/nxhbebom.png)

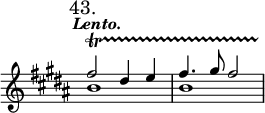

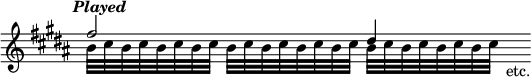

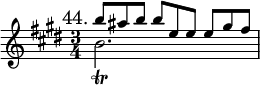

In pianoforte music, a shake is frequently made to serve as accompaniment to a melody played by the same hand. When the melody lies near to the trill-note there need be no interruption to the trill, and either the principal or the subsidiary note (Hummel prescribes the former, Czerny the latter) is struck together with each note of the melody (Ex. 43). But when the melody lies out of reach, as is often the case, a single note of the shake is omitted each time a melody-note is struck (Ex. 44). In this case the accent of the shake must be upon the upper note, that the note omitted may be a subsidiary and not a principal note. [App. p.792 "it should be mentioned that Von Bülow, in his edition of Cramer's studies, interprets this passage in a precisely opposite sense to that given in the Dictionary, directing the shake to be performed as in example 44 of the article."]

Cramer, Study. No. 11.

Beethoven, Sonata, Op. 109.

![{ \new Staff << \tempo \markup \italic "Played." \key e \major \time 3/4

\new Voice \relative b'' { \stemUp \tuplet 3/2 4 { b8 ais b b e, e } }

\new Voice \relative b'' { \stemDown b32*2/3 b, cis b ais'[ b, cis b] b' b, cis b b'[ b, cis b] e b cis b e[ b cis b] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/0/l/0lim2q6994gjeylgcvc0txm6mrab1k1/0lim2q69.png)

The above arrangement constitutes what is called a false trill, the effect of a complete trill being produced in spite of the occasional omission of one of the notes. There are also other kinds of false trills, intended to produce the effect of real ones, when the latter would be too difficult. Thus Ex. 45 represents a shake in thirds, Ex. 46 a shake in octaves, and Ex. 47 a three-part shake in sixths.

Mendelssohn, Concerto in D minor.

Liszt, Transcription of Mendelssohn's 'Wedding March.'

Müller, Caprice Op. 29, No. 2.

![{ \new Staff << \mark "47." \time 4/4

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemUp \repeat unfold 2 {

s32 <a fis c>[ s q s q s q] } \bar "|" \partial 4 s4 }

\new Voice \relative d' { \stemDown

<d g b>32[ s q s q s q] s q[ s q s q s <b d g>] s q8 r } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/9/v/9v37blkyq4rwvpazqk71vy4tznyi8au/9v37blky.png)

The above method of producing a shake in three parts is generally resorted to when great force is required, otherwise the ordinary method is quite practicable, and both double and triple shakes are frequently met with in modern brilliant music (Ex. 48, 49).

Chopin, Polonaise, Op. 25.

Beethoven, Polonaise. Op. 89.

[ F.T. ]

- ↑ Rousseau (Dict. de Musique) describes the Battement as a trill which differed from the ordinary trill or cadence only in beginning with the principal instead of the subsidiary note. In this he is certainly mistaken, since the battement is described by all other writers as an alternation of the principal note with the note below.

- ↑ The exact date of the introduction of the trill is not known, but Consorti, a celebrated singer (1590), is said to have been the first who could sing a trill. (Schilling, 'Lexikon der Tonkunst.')

- ↑ The author of this treatise is said by Playford to have been a pupil of the celebrated Scipione della Palla, who was also Caccini's master.

- ↑ The turn of a trill is better described by its German name Nachschlag or after-beat.