A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Sounds and Signals, Military

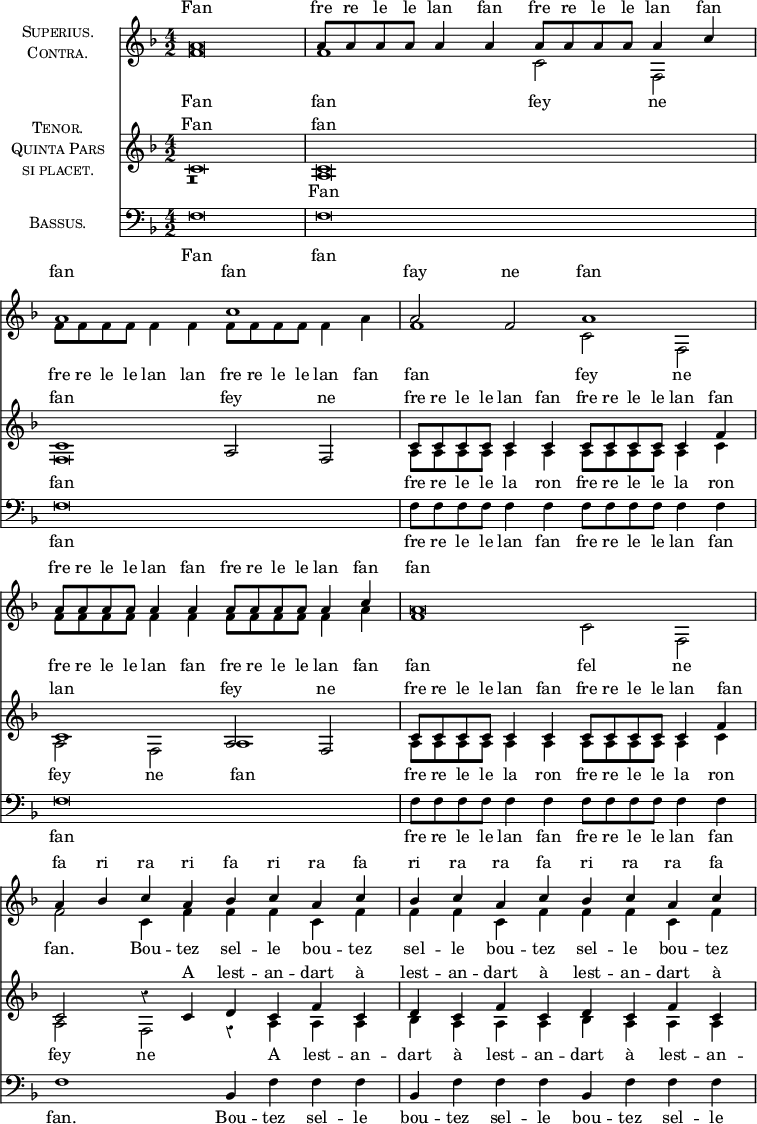

SOUNDS AND SIGNALS, MILITARY. The use of musical instruments in war by the ancients—a use which is found in all countries and at all times—appears to have been more as an incentive to the courage of the troops than as a means of conveying orders and commands. It is in the 13th century of our era that we first find undoubted evidence of the sounding[1] of trumpets in a field of battle as a signal for attack. At the battle of Bouvines (1215) the French charge was signalled in this manner, and numerous other instances are to be found in the chronicles of the period. For the next 200 years at least, the instrument used for signalling seems to have been the trumpet alone. The question of the introduction of the drum into Europe is one involving too much discussion to be entered upon here, but it may be mentioned as a fact that the first clear evidence of its use is the passage in Froissart (Bk. I. Pt. i. chap. 322) describing how in the year 1347, Edward III. and his company entered into Calais 'à grand foison de menestrandies, de trompes, de tambours, de nacaires, de chalemies et de muses'—no mean military band to attend the king of 'unmusical' England! It is in Italy that the drum seems first to have been used for signalling purposes. Macchiavelli, in several passages in his 'Art of War' (written for Lorenzo de' Medici in 1521), clearly states that the drum commands all things in a battle, proclaiming the commands of the officer to his troops. He also recommends the use of trumpets and flutes, the latter being apparently an idea of his own borrowed from the Greeks; he would give the signals to the trumpets, followed by the drums, and advises that the cavalry should have instruments of a different sound from those used by the infantry. This use by the Italians of both trumpets and drums is confirmed by a passage in Zarlino ('Institutione Harmoniche,' Venice 1558, pt. i. cap. 2), 'Osservasi ancora tal costume alii tempi nostri; percioche di due esserciti l'uno non assalirebbe l'inimico, se non invitato dal suono delle Trombe e de Tamburi, overo da alcun' altrà sorte de' musicali istrumenti.' It was from Italy that in all probability the earliest musical signals came: spread over Europe by mercenaries, they were modified and altered by the different troops which adopted them, but the two signalling instruments were everywhere the same (with perhaps the exception of Germany, where the fife seems to have been introduced), and the names given to the different sounds long retained evidence of their Italian origin. The first military signals which have been handed down to us in notation are to be found in Jannequin's remarkable composition 'La Bataille,' which describes the battle of Marignan (1515), and was published at Antwerp in 1545, with a fifth part added by Verdelot. [See vol. ii. p. 31b, and vol. iii. p. 35a.] A comparison of this composition with the same composer's similar part-songs 'La Guerre,' 'La prinse et reduction de Boulogne' (5th book of Nicolas du Chemin's Chansons, 1551; Eitner, 1551 i.), or Francesco di Milano's 'La Battaglia,' would be most interesting, and would probably disclose points of identity between the French and Italian military signals. The second part of Jannequin's 'Bataille' (of which the first 10 bars are given here in modern notation) evidently contains two trumpet calls, 'Le Bouteselle' and 'A l'Etendart.'

In the same year in which Jannequin's 'Bataille' was published, we find in England one of the earliest of those 'Rules and Articles of War' of which the succession has been continued down to the present day. These 'Rules and Ordynaunces for the Warre' were published for the French campaign of 1544. Amongst them are the following references to trumpet-signals. 'After the watche shal be set, unto the tyme it be discharged in the mornynge, no maner of man make any shouting or blowing of hornes or whisteling or great noyse, but if it be trumpettes by a special commaundement.' 'Euery horseman at the fyrst blaste of the trumpette shall sadle or cause to be sadled his horse, at the seconde to brydell, at the thirde to leape on his horse backe, to wait on the kyng, or his lorde or capitayne.' There is here no mention of drums, but it must be remembered that by this time the distinction of trumpet-sounds being cavalry signals and drum-beats confined to the infantry was probably as generally adopted in England as it was abroad. In a Virginal piece[2] of William Byrd's preserved at Christ Church, Oxford, and called 'Mr. Birds Battel,' which was probably written about the end of the 16th century, we find different sections, entitled 'The Souldiers Summons,' 'The March of the footemen,' 'The March of the horsemen,' 'The Trumpetts,' 'The Irish March,' and 'The Bagpipe and the Drum.' The first and fifth of these contain evident imitations of trumpet sounds which are probably English military signals of the period, the combination of bag-pipes and drums being a military march. Jehan Tabourot, in his valuable 'Orchesographie' (1588),[3] says that the musical instruments used in war were 'les buccines et trompettes, litues et clerons, cors et cornets, tibies, fifres, arigots, tambours, et aultres semblables' (fol. 6b), and adds that 'Ce bruict de tous les dicts instruments, sert de signes et aduertissements aux soldats, pour desloger, marcher, se retirer: et à la rencontre de l'ennemy leur donne cœur, hardiesse, et courage d'assaillir, et se defendre virilement et vigourousement.' Tabourot's work contains the first mention of kettle-drums being used by cavalry, as he says was the custom of certain German troops. Similarly in Rabelais we find a description of the Andouille folk attacking Pantagruel and his company, to the sound of 'joyous fifes and tabours, trumpets and clarions.' But though from these passages it would seem as if signals were given by other instruments than the drum and trumpet, there can be no doubt that if this was the case, they were soon discontinued. 'It is to the voice of the Drum the Souldier should wholly attend, and not to the aire of the whistle,' says Francis Markham in 1622; and Sir James Turner, in his 'Pallas Armata' (1683), has the following, 'In some places a Piper is allowed to each Company; the Germans have him, and I look upon their Pipe as a Warlike Instrument. The Bag-pipe is good enough Musick for them who love it; but sure it is not so good as the Almain Whistle. With us any Captain may keep a Piper in his Company, and maintain him too, for no pay is allowed him, perhaps just as much as he deserveth.'

In the numerous military manuals and works published during the 17th century, we find many allusions to and descriptions of, the different signals in use. It would be unnecessary to quote these in extenso, but Francis Markham's 'Five Decades of Epistles of Warre' (London, 1622) demands some notice as being the first work which gives the names and descriptions of the different signals. In Decade I, Epistle 5, 'Of Drummes and Phiphes,' he describes the drum signals as follows: 'First, in the morning the discharge or breaking up of the Watch, then a preparation or Summons to make them repaire to their colours; then a beating away before they begin to march; after that a March according to the nature and custom of the country (for diuers countries have diuers Marches), then a Charge, then a Retrait, then a Troupe, and lastly a Battalion, or a Battery, besides other sounds which depending on the phantasttikenes of forain nations are not so useful.' He also states that a work upon the art of drumming had been written by one Hindar: unfortunately of this no copy apparently exists. Markham is no less explicit with regard to Trumpet Sounds than he is with Drum Signals: 'In Horse-Troupes … the Trumpet is the same which the Drum and Phiph is, onely differing in the tearmes and sounds of the Instrument: for the first point of warre is Butte sella, clap on your saddles; Mounte Cauallo, mount on horseback; Tucquet, march; Carga, carga, an Alarme to charge; A la Standardo, a retrait, or retire to your colours; Auquet,[4] to the Watch, or a discharge for the watch, besides diuers other points, as Proclamations, Cals, Summons, all which are most necessary for euery Souldier both to know and obey' (Dec. III, Ep. i). It is noticeable in this list, that the names of the Trumpet sounds evidently point to an Italian origin, while those of the drum signals are as clearly English. To the list of signals given by Markham we may add here the following, mentioned only in different English works, but of which unfortunately no musical notes are given: Reliefe, Parado, Tapto ('Count Mansfields Directions of Warre,' translated by W.G. 1624); March, Alarm, Troop, Chamadoes and answers thereunto, Reveills, Proclamations (Du Praissac's 'Art of Warre,' Englished by J. Cruso, 1639); Call, Preparative, Battle, Retreat ('Compleat Body of the Art Military,' Elton, 1650); Take Arms, Come to Colours, Draw out into the Field, Challenge, General, Parley ('English Military Discipline,' 1680); Gathering (Turner's 'Pallas Armata,' 1683).

To return to those signals the notes of which have come down to us, the earliest collection extant is to be found in the second book of Mersenne's 'De Instruments Harmonicis,' Prop. xix (1635), where the following cavalry signals are given—L'entrée; Two Boute-selles; A cheval; A l'estendart; Le simple cavalquet; Le double cavalquet; La charge; La chamade; La retraite; Le Guet. Of these signals (copies of which will be found in a MS. of the 17th century in the British Museum, Harl. 6461) we give here the first Boute-selle.

![{ \relative g' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \cadenzaOn

\repeat unfold 3 { g4 c,8[ g'] } g2 c,8[ g']

\repeat unfold 3 { c,[ g'] g4 } c8[ c] g4 c,8[ g'] g4 c8[ c] g4

g8[ c] c[ e] c[ c] g2 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/s/tsr59ee4imnpf75k8de07jxre0h52d0/tsr59ee4.png)

The next collection known is that of Girolamo Fantini, Trumpeter to Ferdinand II., Duke of Tuscany, whose work is entitled 'Modo per imparare a sonare di tromba tanto di guerra quanto musicalmente in organo, con tromba sordina, col cimbalo e ogn'altro istrumento; aggiuntovi molte senate, come balletti, brandi, capricci, serabande, correnti, passaggi e senate con la tromba e organo insieme' (Frankfurt, 1636). This rare work, to which M. Georges Kastner first drew attention in his 'Manuel de Musique Militaire,' contains specimens of the following trumpet-calls—Prima Chiamata di Guerra; Sparata di Butta Sella; L'accavallo; La marciata; Seconda Chiamata che si và sonata avant la Battaglia; Battaglia; Allo Stendardo; Ughetto; Ritirata di Capriccio; Butte la Tenda; Tutti a Tavola. Some of these are very elaborate. The Boute-selle, for instance, consists of an introduction of four bars in common time, followed by a movement in 6-4 time, twenty-nine bars long, which is partly repeated. We give here one of the shorter signals, 'Allo Stendardo':–

![{ \relative g' { \autoBeamOff

r16 g d'8 d d d4 d^\markup \small \right-align "(Three times)." \bar ":|." g8 d d d d4 d | %end line 1

g16[ d g d] d8[ d] d4 d | r16 g, d'8 d4 d d | d1\fermata \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/5/85jilm14yqn4o6qu7ldv05gc05l01xd/85jilm14.png)

With regard to the German signals of this period, and indeed with regard to the whole history of military music in Germany, we are reluctantly compelled to treat the subject very cursorily, owing to the almost total want of material. It has been seen that the use of the kettledrum for the cavalry came from Germany, and frequent allusions are made in French works of the 18th century to the superiority of German military music. But owing perhaps to the more general musical intelligence of the soldiers, the different signals seem to have been handed down orally to a greater extent than they were with other nations. It is said that their signals were better in point of form than those of other nations, and that they were often derived from popular Volkslieder, etc. Their musical superiority they retain to the present day. An interesting point with regard to the German signals is the habit the soldiers had of inventing doggrel verses to them. Some of these rhymes are said to be very ancient, going back so far as the 16th century. The verses were not confined to the signals of their own armies, but were sometimes adapted to those of their traditional enemies, the French. Freiherr von Soltau gives several of these in his work on German Volkslieder (Leipzig, 1845). The following are some of the most striking:—

Wahre di bure

Di garde di kumbt.(1500.)

Hüt dich Bawr ich kom

Mach dich bald davon.(16th cent.)

Zu Bett zu Bett

Die Trommel geht

Und das ihn morgen früh aufsteht,

Und nicht so lang im Bette lëht.

(Prussian Zapfenstreich, or Tattoo.)

Die Franzosen haben das Geld gestohlen,

Die Preussen wollen es wieder holen!

Geduld, geduld, geduld!

(Prussian Zapfenstreich.)

Kartoffelsupp, Kartoffelsupp,

Und dann und wann ein Schöpfenkop',

Mehl, mehl, mehl.(Horn Signal.)[5]

Another probable reason of the scarcity of old collections of signals in Germany is that the trumpeters and drummers formed a very close and strict guild. The origin of their privileges was of great antiquity, but their real strength dates from the Imperial decrees confirming their ancient privileges, issued in 1528, 1623, and 1630, and confirmed by Ferdinand III., Charles VI., Francis I., and Joseph II. Sir Jas. Turner (Pallas Armata, Lond. 1623)[6] has some account of this guild, from which were recruited the court, town, and army trumpeters. Their privileges were most strictly observed, and no one could become a master-trumpeter except by being apprenticed to a member of the guild.[7]

Returning to France, we find from the time of Louis XIV. downwards a considerable number of orders of the government regulating the different trumpet and drum signals. Many of these have been printed by M. Kastner in the Appendix to his Manuel, to which work we must refer the reader for a more detailed account of the various changes which they underwent. In 1705 the elder Philidor (André) inserted in his immense autograph collection [see vol. ii. p. 703a], part of which is now preserved in the Library of the Paris Conservatoire, many of the 'batteries et sonneries' composed by himself and Lully for the French army. The part which Lully and Phillidor took in these compositions seems to have been in adapting short airs for fifes and hautbois to the fundamental drum-beats. See the numerous examples printed in Kastner's Manuel.

From this time the number and diversity of the French signals increased enormously. Besides Philidor's collection, a great number will be found in Lecocq Madeleine's 'Service ordinaire et journalier de la Cavalerie en abregé' (1720), and Marguery's 'Instructions pour les Tambours,' for the most part full of corruptions, and too often incorrectly noted. Under the Consulate and Empire the military signals received a number of additions from David Buhl,[8] who prepared different sets of ordonnances for trumpets, drums, and fifes, which were adopted by the successive French governments during the first half of the present century, and still form the principal body of signals of the French Army.

The history of army signals in France is brought to a close by the restoration last year of the drum to its former position, the ill-advised attempt to abolish it from the army having met with universal disfavour. The French signals are much too numerous for quotation in these pages. They are superior to the English in the three essentials of rhythm, melody and simplicity, but in all three respects are inferior to the German. Perhaps the best French signal is 'La Retraite,' played as arranged for three trumpets.

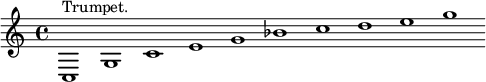

Returning to the English signals, after the Rebellion and during the great continental wars of the 18th century, the English army underwent many changes, and was much influenced by the association of foreign allies. The fife had fallen into disuse, but was reintroduced by the Duke of Cumberland in 1747. Fifes were first used by the Royal Artillery, who were instructed in playing them by a Hanoverian named Ulrich. They were afterwards adopted by the Guards and the 19th, and soon came into general use. Grose (Military Antiquities) alleges that the trumpet was first adopted in 1759 by the Dragoons instead of the hautbois; but this is evidently an error, as by an order of George II., dated July 25, 1743, 'all Horse and Dragoon Grand Guards are to sound trumpets, and beat drums, at marching from the Parade and Relieving.' On the formation of light infantry regiments, drums were at first used by them, in common with the rest of the army, but about 1792 they adopted the bugle for signalling purposes. 'Bugle Horns' are first mentioned in the 'Rules and Regulations for the Formations, Field-Exercise, and Movements, of His Majesty's Forces,' issued June 1, 1792. In December 1798 the first authorised collection of trumpet-bugle Sounds was issued, and by regulations dated November 1804 these Sounds were adopted by every regiment and corps of cavalry in the service. The bugle was afterwards (and still is) used by the Royal Artillery, and about the time of the Crimean campaign was used by the cavalry in the field, although the trumpet is still used in camp and quarters. The use of the drum[9] for signalling is almost extinct in our army, but combined with the fife (now called the flute), it is used for marching purposes. Like many other musical matters connected with the British army, the state of the different bugle and trumpet sounds calls for considerable reform. The instruments used are trumpets in E♭ and bugles in B♭, and though the former are said to be specially used by the Horse Artillery and Cavalry, and the latter by the Royal Artillery and Infantry, there seems to be no settled custom in the service, but—as in the similar case of the different regimental marches—one branch of the service adopts the instrument of another branch whenever it is found convenient. There are two collections of Sounds published by authority for the use of the army—'Trumpet and Bugle Sounds for Mounted Services and Garrison Artillery, with Instructions for the Training of Trumpeters' (last edition 1879); and 'Infantry Bugle Sounds' (last edition 1877). The former of these works contains the Cavalry Regimental Calls, the Royal Artillery Regimental and Brigade Calls, Soundings for Camp and Quarters, Soundings for the Field, Field Calls for Royal Artillery when acting as infantry, and Instructions for Trumpeters. The sounds are formed by different combinations of the open notes of the bugle[10] and trumpet. Their scales are as follow:—

The B♭ of the trumpet is however never used. Many of the English signals are intrinsically good, while many are quite the reverse; and they are noted down without any regard to the manner in which they should be played. A comparison with the sounds used by the German army (especially the infantry signals) shows how superior in this respect the latter are, the rests, pauses, marks of expression, and tempi being all carefully printed, and the drum-and-fife marches being often full of excellent effect and spirit, while in the English manuals attention to these details is more the exception than the rule. Space will not allow us to print here any of the longer signals, either German or English, but the following Sounds may be interesting, as showing the differences between the English and German systems. The sounds are for cavalry in both cases.

| |

![{ \relative c' { \time 4/4 \mark \markup \small "Schritt." \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

c4 c c c8 c16 c | c8 r c16[ c] e8 r c16[ c] c8 r | c4 c c r \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/8/l8jqgf6s1exsn5jr74axkigbdtt7puh/l8jqgf6s.png) | |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

[ W. B. S. ]

- ↑ In connexion with this word we have an instance of Mr. Tennyson's extreme accuracy in the choice of terms. Where the bugle is used as a mere means of awakening the echoes he says—

Blow bugle, blow, set the wild echoes flying';

but where It is to be used as a signal be employs foe strictly correct term—

Leave me here, and when you want me, sound upon the bugle-horn.'

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 422a.

- ↑ See vol. ii. p. 560.

- ↑ Auquet. i.e. Au guet—to the watch.

- ↑ In England similar nonsense rhymes are invented for some of the calls. Their chief authors and perpetuators are the boy buglers. The following Officer's Mess Call is an example:—

- ↑ See also 'Ceremoniel u. Prilegia d. Trompeter u. Paucker' (Dresden, no date. Quoted in Weckerlin's 'Musiciana,' p. 110).

- ↑ Further information on this subject will be found in Mendel, sub voce 'Trompeter,' and in the work quoted in that article: 'Versuch einer Anleitung zur heroisch-musikalischen Trompeter-und-Pauken-Kunst' (Halle, 1795).

- ↑ See vol. i. p. 281.

- ↑ Some of the Drum-beats will be found in vol. i. p. 466 of this Dictionary.

- ↑ See vol. i. p. 280.