Archaeological Journal/Volume 1/Military Architecture

THE

Archaeological Journal.

JUNE, 1844.

MILITARY ARCHITECTURE.

The military works of the Saxons were formed by throwing the contents of a ditch inwards as a rampart, upon the ridge of which they appear in some cases to have placed a palisade of timber. The spot chosen was usually the top of a hill, and the figure of the entrenchment depended upon the disposition of the ground. Additional banks and ditches were added upon the less steep sides, and the road winding up from below passed obliquely through the defences.

In more permanent intrenchments a wall was constructed upon the outer face of the mound. The Romans, whose works were defended on this principle, called the ditch, bank, and wall, the fossa, agger, and vallum[1].

The Romans, who carried heavy baggage, trusted more to the discipline of their sentinels, and cared less for a distant view. Their field works lie in the lower country, and though formed of earth, are set out by the rules of castrametation, and are commonly rectangular, with two or four entrances[2].

Their permanent stations were constructed upon a greater scale. A rectangular area[3] was enclosed by a thick wall, from fifteen to twenty feet high, strengthened by buttresses, or towers projecting externally, and a ditch. The 'Prætorian' and 'Decuman' gates were in the middle of opposite sides, and the 'Principal' gates were similarly placed in the remaining sides, the roads crossing at right angles in the centre. The direction of the main streets of Chester, Wallingford, and Caerwent, shew the Roman origin of each place. The material employed in Roman buildings is that of the country, the work frequently herringbone, or some Roman pattern, with occasional bonding-courses of flat Roman brick. A mail coach road still enters old Lincoln under the Roman arch, and the road from Chepstow to Newport passes through the Prætorian and Decuman entrances of Caerwent.

These Roman works, however, are rather walled camps than castles. It is certain that the Conqueror found no fortress in England at all resembling those whose ruins have descended to the present day. William, however, constructed very many castles, and before the death of Stephen their number is said to have amounted to eleven hundred and fifteen.

These castles at first supported the Sovereign; but as the feudal system took root, they by degrees became obnoxious to his power. By a treaty between Stephen and Henry Duke of Normandy, many of the later castles were rased, and upon Henry's accession to the crown he destroyed many more. Power to grant a Licentia kernellare et tenellare, or permission to crenellate or embattle and to make loop-holes for defence in the walls of a dwelling, became a part of the royal prerogative.

The crown castles were held by constables or castellans, and the feuars of the castle lands held them by tenures, chiefly military, and connected with the defence of the castle, or of the lord when residing in it. The twelve knights of Glamorgan held their estates by the tenure of castle guard at Cardiff, and the Stanton tower at Belvoir, was long repaired by the family of Stanton, whose arms were a grant from the lords of that castle. The Tower, Dover, Windsor, St. Briavel's, and other crown castles, are still held by constables. Castle guard was abolished with the other feudal tenures by Charles II.

The general type of a Norman castle was composed of the following parts.

The keep. The walls of the enceinte. The base court. The mound and donjon. The ditch.

The Norman keep, both in England and Normandy, is commonly formed after one model. Its plan is a square or oblong, its height from one to two squares[4], strengthened along the sides by the usual flat Norman buttress[5] rising from a general plinth, and dying into the wall below its summit. The end pilasters of each face unite at and cap the angle, and rise a story above the walls to form four angular turrets[6]. The wall at the base is from twelve to eighteen, or even twenty-four feet thick, and diminishes usually by internal offsets to eight or ten feet at the top, with a battlement of from one to two feet thick.

The lower openings are loops, the upper the usual Norman window, frequently double and of a good size, as in the keep at Goodrich.

The entrance is usually by an arched door upon the first floor, placed near one corner, and approached by stairs parallel to the wall. The stair is either defended by a parapet or arched over, when the whole forms a smaller square tower appended to the keep, and reaching, as at Newcastle and Dover, to its second story. This appendage is commonly applied to the east side of the keep. Sometimes, however, as at Prudhoe, Canterbury, and Ogmore, co. Glamorgan, the only entrance appears to have been by a small portal on the ground floor; in other cases, as Dover, Portchester, and Newcastle, both methods are employed.

The ground floor is sometimes vaulted; at Portchester, Newcastle, and Bowes, the groins spring from a central column. The upper floors are usually of timber. Newcastle is a rare instance of an apparently original vault in the upper story.

Large keeps, as London, are sometimes divided by a wall into two parts; but commonly, as at Hedingham, Rochester, and Beaugency near Caen, upon the principal floor an arch springs from wall to wall, with perhaps an intermediate column dividing it into two and carrying the upper floor beams.

The walls are hollowed out at different levels into staircases, galleries, chambers for bedrooms, chapels, sewers, and openings for various purposes[7]. The windows are splayed so as to form a large interior arch, and the galleries thread the walls and open in the jambs of the windows like the triforial galleries of a cathedral. Usually, as at London, Hedingham, and Newcastle, the uppermost gallery runs quite round the building, communicating with each window without entering the great room. At one angle a spiral stair rises from the base to the summit, and opens into each floor and gallery.

The mural chambers are sometimes ribbed, the galleries have the usual barrel vault.

The principal floors have fire-places with ascending flues. At Ogmore and Rochester, the fireplaces are handsomely worked; at Rochester the flue is wanting, and the smoke escapes outwards by a guarded vent a little above the hearth. At Bamborough there appear to be no flues. At Dover the flues are said to be original, but the fire-places are very late Perpendicular. They open from the mural chambers instead of from the principal rooms.

The well is commonly in the substance of the wall, through which its pipe, of from 2 feet to 2 feet 9 inches diameter, ascends to the first and second stories, opening into each[8]. At Newcastle and Dover the pipe terminates in a small chamber, and has no other aperture. In some castles a similar pipe seems to have been used for the passage of stores and ammunition to the battlements.

At Portchester, Bamborough, Oxford, and Castleton, are traces of an original ridge and valley roof; this also appears in an old drawing of London. The large arches sometimes seen in the wall above the line of the roof, seem intended for the play of military engines placed in the valley of the roof. At Portchester this arrangement causes the east and west ends to rise as low gables, battlemented.

The walls and turrets were probably surmounted by a battlement, but those now seen are rarely if ever original. Machicolations are described in some of the castles near Caen, but they are probably additions.

The portal seems to have been closed by a hinged door, secured by one or two wooden bars sliding into the wall, as in the lower portal of Dover. At Hedingham are grooves for a portcullis, but this is rather unusual[9].

The Norman keep is not always quadrangular. Orford is a multangular tower of great solidity, ninety feet high, of small circular area within, and heavily buttressed without. Coningsborough is of the same class: the base story is domed, and the door in the upper story was probably approached by a temporary stair. These keeps seem to be of late Norman date. Tretower, Skinfrith, and Brunlys towers in S. Wales, are probably of the same class. The Cornish circular towers, as Trematon, Launceston, and Restormel, have not been critically examined.

The materials of Norman keeps are usually the rubble-stone of the country, sometimes faced, and always groined and dressed with ashlar. When constructed upon a Roman site, the old materials were employed, and sometimes the herringbone and other old styles of work were introduced[10]. The work is generally good. Coningsborough, both inside and out, is, even now, one of the finest specimens of ashlar extant. The whole interior of Rochester is highly decorated, and the entrance, upper windows, and fire-places, are usually more or less so. The chimney-pieces of Rochester and Coningsborough, and the portal of the latter, are stone platbands, the parts of which are joggled together, and have stood well over a wide space with little or no abutment. Prom its great solidity and simple figure, the Norman keep is more durable than later structures, and continues, as at London, Dover, Bamborough, Rochester, Prudhoe, to give the distinguishing feature to the fortress through every subsequent addition.

The wall of the enciente. The keep occasionally forms a part of the circuit of the Avail, as at Portchester, Rochester, Castleton, Richmond, Oxford, and Coningsborough; at Dover and Prudhoe it stands in the centre. The masonry of the Norman walls was inferior to that of the keep, and where these have not been removed they have generally fallen into decay. Their height was from 20 to 25 feet, and their general plan either irregular, as at Coningsborough, Richmond, and Dover, or circular, as at Oxford. At Richmond and Hastings they enclose a considerable space, but more commonly, as at Oxford, Coningsborough, and Newcastle near Bridgend, the area is very small. Prudhoe, on the south bank of the Tyne, affords a rare instance of a Norman keep, with both its own and a second or supplementary enclosure on one side, with a gate-house and ditch all Norman. The outer gate-house, though late Norman, has no portcullis. At Portchester the keep occupies one angle of the Roman enclosure, and at Lincoln the castle wall stands upon the wall of the Roman city.

The Norman buttress-towers were few, and their exterior projection small, as at Ludlow, Middleham, and Richmond. They rarely constructed a regular gate-house, but erected two towers near to each other. Good examples of Norman entrances remain at the inner bailey Dover, and at Newcastle, near Bridgend. Sometimes, as at Cardiff, access to the walls is rendered easy by a bank of earth behind them.

A Norman wall may usually be detected by its dressed quoins, flat buttresses, and its square buttress-towers of little or no interior projection, as at Lincoln, Coningsborough, Chester, and Carlisle. The battlements of Orford wall are possibly Norman, but it is probable that they used sometimes the plain parapet, sometimes the parapet notched at long intervals. The wall, towers, and gates of the inner bailey of Dover are Norman, as is part of the battlement, and the whole form a very fine example.

The base-court contained garrison lodgings and offices, and often a second wall.

The mound[11], or mote, is a tumulus of earth, from 30 to 60 feet high, and from 60 to 100 feet diameter at the top. At Cambridge it stands without, at Cardiff within the walls, in some instances it forms part of their circuit. Within a radius of twenty leagues of Caen are sixty castles with these mounds.

They have not been carefully examined. That at Oxford contains a ribbed Norman chamber and well in its base, accessible by steps from the summit. At Wallingford, the well is in the side. These mounds were certainly thrown up by the builders of the castles, and could not have supported any heavy load; occasionally, they appear to have been crowned by a light shell of wall, circular or multangular[12], regularly embattled for defence, but not roofed over, or so roofed as to leave an open court in the centre. Part of that at Tamworth is a Norman tower, with a curtain wall, shewing herring-bone masonry. These buildings probably are founded as deep as the bottom of the mound.

The ditch was either wet or dry, according to circumstances; where the place is defended naturally, as at Castleton or Peak Castle, it is omitted.

The Early English period, rich in ecclesiastical, is poor in military structures. Walls and buttresses were added, but the ornaments of the style are rare. The middle wall of London was the work of Henry III., 1239; and one of the towers contains a groined Early English chamber. There are also Early English additions to the keep. The gateways of the inner bailey at Dover, with their portcullis, though Norman, bear some features of the Early English style.

Much of Cardiff is Early English, upon a Norman foundation, as are the additions to the keep of Chepstow. The chapel in Marten's tower, with its ball-flower moulding, and part of the wall, is late in this style. The ruins of Cambridge seem to be Early English, as are parts of the outer bailey of Dover. Some of the small castles erected in Glamorganshire, of Fitzhamon's sub-infeudatories, were in the Early English style, though for the most part on a Norman ground-plan. Ogmore is decided Norman. Sully, the ground-plan of which has been recently excavated, appears to have been upon a Norman plan, but the work is decided Early English. The fine circular keep of Coney, near Caen, 200 feet high, and vaulted in every story, the chateau of Gisors, and other circular towers, are executed in this style.

In the works of this period there was a tendency to economize men and material by a more skilfid disposition of the parts of the fortification.

The Norman castle held a small garrison, who trusted to the passive resistance of their walls; their successors diminished the solidity to increase the extent of their front, and by throwing out salient points were enabled to combine their forces upon any one point. A wall cannot be advantageously defended unless so constructed that the exterior base of one part can be seen from the interior summit of another; hence the advantage of buttress or flanking towers, which not only add to the passive strength of the line, but enable the garrison to defend the intermediate or curtain wall. By this means, the curtain, that part of the line of defence least able to resist the ram, became that in defence of which most weapons could be brought to bear, whilst the towers which had not the advantage of being thus flanked, were, from their form and solidity, in but little danger of being breached. If we suppose a square or polygon to be fortified by a wall, with towers at its angles, it is evident that the centre of each curtain wall, midway between its towers, will be passively the weakest part of the wall, but that in defence of which most weapons can be directed; and the centre of each tower, midway between its curtains, will be the strongest part of the work, but that in defence of which fewest weapons can be directed; or, in other words, if from the centre of a polygon we draw straight lines, passing one through each of its angles, and one midway through each of its sides, the prolongations of the former will be the safest, the prolongations of the latter the most exposed directions in which an enemy can approach.

Lines drawn from the centre of a place through its angles are called "capitals;" they are the lines of approach at present employed.

The changes introduced with the thirteenth century assumed a determinate form under Edward I., and produced the second great type of English castle, the "Edwardian" or Concentric.

In the Edwardian castle, the solid keep becomes developed into an open quadrangle, defended at the sides and angles by gate-houses and towers, and containing the hall and state apartments ranged along one side of the court. The term keep is no longer applicable, and around this inner ward, or bailey, two or three lines of defence are disposed concentrically. Such castles frequently enclose many acres, and present an imposing appearance[13].

The parts of a perfect Edwardian castle are:—The inner bailey, the walls of the enceinte, single, double, or triple. The middle and outer baileys contained between the walls. The gate-houses and posterns. The ditch. The inner bailey contained the hall, often of great size, the chapel, the better class of apartments, and an open court. The offices usually were placed in the middle bailey, on the outside of the wall of the hall. The outer bailey contained stabling, at Caerphilly a mill, at Portchester and Dover a monastery, and often a moderate sized mound of earth or cavalier to carry a large engine. The walls were strengthened by "mural," or towers projecting inwards, but flush with the face of the wall, and "buttress-towers" projecting outwards beyond it. These towers were sometimes circular, as at Conway and Caerphilly; sometimes square or oblong, as at Dover and Portchester; sometimes multangular, as at Caernarvon and Cardiff. The Beauchamp tower at Warwick is a fine example of a multangular tower, as is Guy's tower of one formed of portions of circles. Such towers were all capable of being defended independently of the castle, and usually opened into the court and upon the walls by portals, regularly defended by gates and a portcullis. The fine bold drum-towers that flank the outer gateway of so many castles, as Chepstow, Beaumaris, &c., are Edwardian. Circular and octagonal towers of this age frequently spring from a square plan or base, the angles of which gradually rise as a half pyramid cut obliquely until they die away into the upper figure of the tower towards the level of the first story. These towers are common in Wales, as at Marten's tower, Chepstow; Castel Côch, near Cardiff; Carew castle, near Pembroke; Newport, Monmouthshire, &c. This description of tower also occurs next the Constable's gate at Dover.

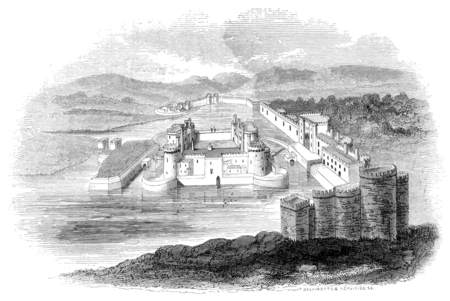

The gate-houses are distinct works, covering the entrance: Caerphilly restored from a careful survey, by G. T. Clark.

The draw-bridge dropped from the front of the gate; when the ditch was broad, a pier was erected in it, and the space spanned by two bridges, as at Holt and Caerphilly. The barbican was an outwork, or tête du pont, on the outside the counterscarp of the ditch. It seems to have been commonly of timber, so that when deserted, as it was intended to be, at a certain period of the siege, it might be burnt, and thus afford no cover to the assailants. The barbican of the tower of London is of stone, and evidently intended to be defended throughout a siege. There is a very complete stone barbican at Chepstow, Another description of barbican was attached to gates, viz., a narrow passage between walls in advance of the main gate, with an outer gate of entrance, as at Warwick and the Bars at York.

The posterns were either small doors in the wall, or if for cavalry were provided with smaller gatehouses and drawbridges.

The ditch was usually wet. At Caerphilly, Kenilworth, Berkhampstead, and Framlingham, a lake was formed by damming up the outlet of a meadow.

The top of the wall was defended by a parapet, notched into a battlement; each notch is an embrasure, and the intermediate piece of wall is a merlon. The coping of the merlon sometimes bears stone figures, as of armed men at Chepstow and Alnwick, at Caernarvon of eagles. Sometimes the merlon is pierced by a cruciform loop, terminating in four round holes or oillets.

In many cases a bold corbel-table is thrown out from the wall, and the parapet placed upon it, so as to leave an open space between the back of the parapet and the face of the wall. This space is divided by the corbels into holes called machicolations, which overlook the outside of the wall, as at Hexham and Warwick, or later at Raglan, and later still at Thornbury. If the parapet be not advanced by more than its own thickness, of course no hole is formed; this is called a false machicolation, and is used to give breadth to the top of the wall. It is common to all periods, being found upon Norman walls as well as upon those of late Perpendicular date, as Coity and Newport.

Some of the smaller Edwardian castles in Wales are very curious; that of Morlais, near Merthyr, has a circular keep of two stories, of which the lower is internally a polygon of twelve sides, with a vault springing from a central pier. The up-filling of the vault is a light calcareous tufa. This castle contains within its enclosure a singular pit, twenty-five feet square, and excavated upwards of seventy feet deep in the mountain limestone rock. It was probably intended as a well, though a clumsy one. The ruins of a somewhat similar castle remain at Dinas, near Crickhowel. The upper story of the tower of Morlais, as of Castle Côch, contains a number of large fire-places; something of the same sort is seen at Coningsborough, with the addition of an oven.

The Edwardian castles are frequently quite original[14]; they occur also as additions encircling a Norman keep, as at Dover, Portchester, Bamborough, Corfe, Goodrich, Lancaster, Carlisle, and Rochester. Edward I. completed the tower-ditch of London. The existing walls of towers are commonly Edwardian, though on an older foundation, as York, Canterbury, Chester, Chepstow, and their various bars and gates.

The Norman and Edwardian, the solid and concentric, may be regarded as the two great types of English castles, of which other military buildings are only modifications. After the death of Edward III., the Decorated gave place to the Perpendicular style; and though a few fine castles, and very many embattled gateways[15], continued to be erected, far less attention was paid to their defences, and more to their internal convenience. The introduction of gunpowder, by rendering a lofty wall an evil rather than a safeguard, led to the construction of a description of edifice having no pretension to withstand artillery, and in which the lofty turrets, embattled gateways, and moat of the ancient castle, were combined with the slight wall, exposed roof, and spacious windows of a modern dwelling. This description of building, sometimes called a Castle, but more properly a Hall, belongs rather to domestic than military architecture, although some of them present a very warlike appearance, and were effectively defended under Charles I.

As the country became more peaceful, those who possessed old castles found them inconvenient dwellings. Some were altered, as Powis castle; others pulled down, as Queenborough; and the materials employed in the construction of a new house, as that of the Van from Caerphilly; others left in ruins, as Hedingham, Rochester, Prudhoe, Canterbury; and some were converted into prisons and store-houses, as Portchester and London, Dover and Newcastle.

A sort of Peel-tower, with bold machicolations, as at Hexham and Morpeth, or with bartizans at the angles, as in Tynemouth and Cockle-park tower, continued to be erected and defended on the Northumbrian border, until the union of the two crowns under James, when these also fell into disuse.

Henry VIII., anno 1539, erected a number of block-houses, something between a castle and fort, with a round tower, casemates, embrasures, and a moat, upon the southern coast of England; some of these, as Sawdown, near Deal[16], have been preserved; others, as Brighton, have been destroyed.

Many old castles were hastily repaired during the wars between Charles and his Parliament, and strengthened with earth-work according to the system of that day, as may be seen at Caerphilly; Donnington, Berks; and Dover; these when taken were commonly blown up, and it is to this period that we owe the leaning ruins of Corfe, Bridgenorth, and Caerphilly.

In the absence of ornaments, circles, and buttresses, in the ruins of a castle, the thickness of the walls, and the general disposition of the foundations, will usually afford some clue to the date.

The following may be considered as an approximation to the number of the castles, and remains of castles, in Britain:—

|

|

|

|

- England

461

- Wales

107

- Scotland

155

- Ireland

155

- Great Britain and Ireland, about

843

This number, however, if accurate search were made, would probably be found nearer to a thousand.

G. T. CLARK.

- ↑ Bower walls, Bristol.

- ↑ Bitton and Lansdown, near Bath; Wallingford.

- ↑ Portchester, 41/2 acres; Richborough; Pevensey; Burgh; Lincoln; Silchester.

- ↑ Rochester, 70 feet by 70 feet, and 104 feet high. London, 116 by 96, and 69 feet high. Canterbury, 87 feet square and 50 feet high. Newcastle on Tyne, 60 by 60, and 80 feet high. Guildford, 44 by 44, and 70 feet high. Castleton, 38 feet square. Bowes, 75 by 60, and 53 feet high, all exclusive of turrets. The inequality in the dimensions is chiefly caused by the exterior stair on one side.

- ↑ At Loches they are parts of circles.

- ↑ At London one turret is round; at Newcastle one is multangular; Colchester and London have semicircular projections from one side.

- ↑ At Newcastle, the chapel, a beautiful one, is under the stairs. At Coningsborough, it occupies part of a buttress, and there is a piscina in each upper story, London and Colchester contain regular Norman churches. At Ludlow the chapel is circular. Bamborough has a chapel. The chapel at Dover is in the entrance tower; it is a fine example of late Norman.

- ↑ Canterbury; Dover; Rochester; Kenilworth; Portchester; Carlisle.

- ↑ Among the quadrangular Norman keeps, are Norwich, Oxford (which appears to have been intended also for the tower of a church 1078); London (1079); Newcastle (1080); Ogmore (circa 1100); Bamborough; Bowes; Bridgend (destroyed); Bridgenorth; Bristol (1147 destroyed); Brough; Brougham; Canterbury; Carlisle; Chepstow; Chester; Corfe; Colchester; Clitheroe; Dover (Henry II.); Falaise; Goodrich; Guildford (late Norman); Hedingham; Helmsley; Kenilworth; Lancaster; Lewes; Loches; Middleham; Penline; Prudhoe; Peak.

- ↑ As at Penline, Tamworth, Colchester, Corfe, and Guildford, the latter late Norman; also in the south-west staircase at Canterbury.

- ↑ Norman mounds remain at Bedford, Berkhampstead, Cainhoe, Carisbrook, Christ Church Castle, Cambridge, Clare, Cardiff, Durham, Eaton-Socon, Fontenay-le-Marmion, Hinckley, Lewes, Lincoln, Marlborough, Oxford, Pleshy, Pevensey, Risinghoe, Sandal, Tamworth, Tonbridge, Toddington, Worcester (now destroyed), Wallingford, Warwick, Windsor, Yielden, York. At Château sur Epte, in Normandy, there are two mounds, one within and one forming part of the enclosure. At York and Canterbury are mounds just within the city walls. In modern fortifications they are called Cavaliers. There is one in the citadel of Antwerp.

- ↑ The shell or remains of it are seen at Château-Gaillard, built by Richard I., Oxford, Cardiff, Durham, Clifford's tower at York, Lincoln, Clave, Tamworth, Carisbrook.

- ↑ Bernard's castle includes seven acres. The Tower of London, within the walls, twelve. Windsor and Caerphilly still more.

- ↑ Among the castles either originally constructed, or thoroughly re-edified in this style, are Cilgarran, 1222; Flint and Rhuddlan, 1275; Hawarden and Denhigh about the same time; Caernarvon, 1283; Conway, modified in plan by its position, 1284; Beaumaris, 1295; Caerphilly, Harlech, Morlais, the same reign; Queenborough, 1361; Cowling and Raby, 1378; Bolton castle, and the west gate of Canterbury, in the same reign; most Dudley and Warwick are a little earlier.

- ↑ The gateway of St. Augustine's, and the west gate of Canterbury, the one Early Decorated, and the other Perpendicular, afford a fine example of the contrast between monastic and military architecture. The west gate is one of the finest city gateways in England, hut its drawbridge is destroyed, as is its connexion with the city wall on each side.

The gateways of Leicester castle and Alnwick abbey are both Perpendicular; Newport, Monmouthshire, and St. Donat's, Glamorganshire, still later; Caistor, Henry V. and VI.; part of Coity and Rye House, Henry VI.; Fowey towers, of Edward IV.; Raglan, the great gate of Carisbrook, Nettle Hall, Essex, Henry VII.; Buckenham, Essex, and Tatershall, are both very late Perpendicular; Thornbury 1511, and Tichfield house the same reign.

- ↑ Warblington, Hants, belongs to the reign of Henry VII.; West Cowes, Camber, Fowey Castle, Hurst, Motes Bulwark, Sandford, Sandgate, and South-sea castles, were erected circa 1539, and Upnor in 1549.