Archaeological Journal/Volume 1/Proceedings of the Central Committee (Part 4)

PROCEEDINGS OF THE CENTRAL COMMITTEE

of the

British Archaeological Association.

September 28.

Mr. T. Crofton Croker read an account of further excavations of barrows on Breach Downs, made subsequent to the Canterbury meeting.

"On the 16th of September, 1844, Lord Albert Conyngham resumed his examination of the barrows on Breach Downs, and opened eight more in the presence of the Dean of Hereford and Mr. Crofton Croker.

In No. 1. The thigh bones and scull were found much decayed; close by the right hip was a bronze buckle, which probably had fastened a leather belt round the waist, in which had been placed an iron knife, the remains of one being dis- covered near the left hip of the skeleton.

No. 2. The only thing found in this grave was a very small fragment of a dark-coloured sepulchral urn, with a few small bones, and the jaw of a young person in the process of dentition.

No. 3. The bones in this grave were much decayed. Several fragments of iron were found near the head, and on the right side of it a bronze buckle, very similar to that found in No. I. but rather smaller. By the left side of the scull an iron spear-head was discovered, about ten inches in length.

No. 4. In this grave the bones were remarkably sound, and were those of a very tall man; the thigh bone measured twenty inches. An ornamental bronze buckle was found on the right hip, attached to a leather belt, which crumbled to pieces upon exposure to the air, and the right arm was placed across the body. To the buckle was attached a thin longitudinal plate of bronze, which had two cross-shaped indentations or perforations in it, and the face of the plate was covered over with engraved annulets.

No. 5. Presented a skeleton, in the scull of which the teeth were quite sound and perfect. At the feet some iron fragments were found, supposed to be parts of a small box, and this, on subsequent examination, has proved to be the case, as a hinge of two longitudinal pieces of iron connected by a bronze ring has been developed. At the right side was part of an iron spear or arrow-head.

No. 6. In this grave the bones were so much decayed that they could only be traced by fragments mixed up with the chalk rubble, and the only article found was the remains of an iron spear-head.

No. 7. Although it was conjectured from the confused state in which several beads and other articles were found in this grave that it had before been opened, it was the most interesting of the eight. At the foot several broken pieces of a slight sepulchral urn of unbaked or very slightly baked clay, some of them marked with patterns, were discovered; and also fragments of iron presumed to have been parts of a small box. An iron knife was found on the left side of the body, which appeared from the jaw being in the process of dentition to have been that of a young person, and probably a female, from the discovery of the following beads about the neck and chest:—

Three beads of reddish vitrified clay; a spiral bead of green glass; a bead of green vitrified clay; an amethystine bead of a pendulous form; a small bone bead, and a small yellow bead of vitrified clay, with a small bronze pin not unlike those at present in common use, except that the head appeared as if hammered out or flattened, and close under it, and about the centre of the pin, ran three ornamental lines.

No. 8. Was remarkable from the body having been buried at an angle with the other interments, lying nearly north and south (the head to the south). The scull was a finely formed one and evidently that of a very old man. Nothing besides the bones was discovered in this grave.

On the 17th of September, Lord Albert Conyngham accompanied by Mr. Crofton Croker, resumed the examination of the barrows at Bourne, in the vicinity of those which had been opened in the presence of the members of the British Archæological Association on the 10th instant. In the first grave opened some fragments of bone were found in a state of great decay, and a small bit of green looking metal, (supposed to have been part of a buckle,) near the centre of the grave. From another barrow part of a bone ornament or bead, stained green as was conjectured from contact with metal was obtained. Several mounds which appeared like barrows were examined, and it was ascertained they did not contain graves.

A slight examination of two or three barrows upon Barham Downs, most, if not all of which are known to have been opened by Douglas, was entered upon, but nothing beyond several fragments of unbaked clay urns was turned up.

It is remarkable that large flint stones are found at the sides and at the head and feet of almost all the graves examined at Breach Downs and Bourne; from which it is presumed that these flints might have been used to fix or secure some light covering over the body in the grave before the chalk rubble, which had been produced by the excavation, was thrown in upon it.

Mr. Wright read the following communication from the Rev. Harry Longueville Jones, relating to the neglect and destruction of some churches in Anglesey:—

"The church of Llanidan stood close behind the house of Lord Boston, the church-yard wall being the boundary of his lordship's premises, and one of the areas of the house passing slightly under the church-yard. The church itself was a building principally of the Decorated period, but a north aisle, going the whole length of the edifice, was of late Perpendicular work. The church consisted of a central aisle, that on the north just mentioned, and a southern transept or chapel, which might have corresponded to a northern transept or chapel, before the north aisle was added: this chapel or transept was of early and very rude Decorated work. The east window of the central aisle was of good Perpendicular execution, but of singular design. There was a south porch to the nave, and a bell-gable at the west end, stayed up by strong buttresses, the walls having apparently given outwards at this spot. I arrived at this church (July, 1844) at a period when the roof had been completely stripped off, and all the wall between the south transept and the south porch had been pulled down: the workmen were then building a wall across the nave so as to convert the two western bays of it and of the north aisle into a chapel, which I was informed was to be used in future for the performance of the burial service. All the walls of the church, then standing, all the pillars, all the windows with their mullions, with the exception of the wall at the west end under the bell-gable, were in perfectly sound condition, very good in their masonry, quite vertical, without any symptoms of decay. The only part of the church that seemed weak was that part which the workmen were then converting into a chapel. The roof which had been taken off was good, and the timber had been purchased by a gentleman in the neighbourhood to use in the repairs of his house, and were of excellent oak (commonly called chesnut.)

"Now, it may be asked, why should this church have been demolished: was it ruinous? Certainly not: £200 or £300 at the outside would have rebuilt the west end and reshingled the roof. Was it too small? apparently not; for the new church built to replace it does not occupy a greater area. The new church built on a spot about a mile distant, is of most barbarous pseudo-Norman design: of stout execution apparently, but not stouter than the old edifice, and it has been erected at a cost of upwards of £600.

"Many of the details of the old church were exceedingly valuable; there were several stones bearing armorial shields; the font was a very remarkable one, and it lies in the part now converted into a chapel: there was a famous stone kept in the old church to which one of the most interesting legends of the country was attached. Fortunately I was able to measure and carefully delineate every portion of the edifice as it then remained.

"The church of Llanedwen in the grounds of Plas Newydd, (the Marquis of Anglesey's,) a building in perfectly good condition, and of high interest from various circumstances attending it, is also threatened with demolition.

"The church of Llanvihangel Esgeifiog, one of the most curious churches in the island, (of the early Perpendicular period,) of beautiful details, and quite large enough for the parish, has been abandoned, because the roofs of the south transept and part of the central aisle want repair. About £300 would restore this church completely, a new one will cost from £000 to £700. It is said that it is to be pulled down shortly, and a new one built in another part of the parish.

"The churches of Llechylched and Ceirchiog, as well as the church of Llaneugraid (the latter one of the earliest and most valuable relics of the island) have been abandoned for some time past; their windows are mostly beaten in, without glass, and they serve only as habitations for birds, which frequent them in flocks. Service is performed in them only for burials, the inhabitants go for worship to other neighbouring churches."

An abstract of Mr. Jones's letter was ordered to be forwarded to the Bishop of Bangor, and to the Archdeacon of Bangor.

My. Smith read a communication from Mr. George K. Blyth, of North Walsham, on some Roman remains recently discovered at about three miles from that town.

"Some labourers on the farm of Mrs. Seaman, of Felmingham Hall, Norfolk, were carting sand from a hill, when part of the sand caved in and exposed to view an earthen vase or urn, of a similar shape to the annexed, covered with another of the same form, but coarser earth; the top urn or cover had a ring-handle at the top, within were several bronze or brass figures, ornaments, c.; the bottom vase is very perfect, and made of a similar clay to that called 'terra cotta.' Amongst the brasses a female head and neck, surmounted with a helmet, like to that we see on the figures of Minerva, the face is flattened and the features rather bruised; an exquisite little figure about 3 inches, or 31/2 high, holding in one hand either a bottle or long-necked cruet, and in the other a patera, or cup, probably intended for a Ganimede, certainly not a faun; a larger head, thick necked, close curling hair and beard, features well formed, the scalp made to take off, evidently only part of a figure, originally from 18 inches to 2 feet in height, not unlike some drawings I have seen representing Jupiter; this specimen is hollow, and the eyes are not filled. A small square ornament, something like an altar, stands upon four feet; a small wheel; a pair of what appear to have been brooches or buckles with heads in the centre; two birds, one holding a pea, or something round, in its beak, these were originally attached to something else, probably handles to covers; a round vessel, very shallow, about 10 or 11 inches in circumference, having a top and bottom soldered together, but now separated, the top having a hole in the centre about the size of a sixpenny piece; two small round covers; a long instrument about 11/2 feet, not unlike a riding-whip in form, of the same metal, it has an ornamented handle, and terminates in shape to a spear-head, but at the point it finishes with a round; another, similar to the above, the handle gone; the head differs in being double, two spears at right angles springing from the same point with small wings at the bottom of each edge; several narrow strips of the same metal, one apparently intended to be worn at the top of the mantle or tunic, just below the throat, the others are of various lengths."

"Some labourers on the farm of Mrs. Seaman, of Felmingham Hall, Norfolk, were carting sand from a hill, when part of the sand caved in and exposed to view an earthen vase or urn, of a similar shape to the annexed, covered with another of the same form, but coarser earth; the top urn or cover had a ring-handle at the top, within were several bronze or brass figures, ornaments, c.; the bottom vase is very perfect, and made of a similar clay to that called 'terra cotta.' Amongst the brasses a female head and neck, surmounted with a helmet, like to that we see on the figures of Minerva, the face is flattened and the features rather bruised; an exquisite little figure about 3 inches, or 31/2 high, holding in one hand either a bottle or long-necked cruet, and in the other a patera, or cup, probably intended for a Ganimede, certainly not a faun; a larger head, thick necked, close curling hair and beard, features well formed, the scalp made to take off, evidently only part of a figure, originally from 18 inches to 2 feet in height, not unlike some drawings I have seen representing Jupiter; this specimen is hollow, and the eyes are not filled. A small square ornament, something like an altar, stands upon four feet; a small wheel; a pair of what appear to have been brooches or buckles with heads in the centre; two birds, one holding a pea, or something round, in its beak, these were originally attached to something else, probably handles to covers; a round vessel, very shallow, about 10 or 11 inches in circumference, having a top and bottom soldered together, but now separated, the top having a hole in the centre about the size of a sixpenny piece; two small round covers; a long instrument about 11/2 feet, not unlike a riding-whip in form, of the same metal, it has an ornamented handle, and terminates in shape to a spear-head, but at the point it finishes with a round; another, similar to the above, the handle gone; the head differs in being double, two spears at right angles springing from the same point with small wings at the bottom of each edge; several narrow strips of the same metal, one apparently intended to be worn at the top of the mantle or tunic, just below the throat, the others are of various lengths."

Mr. Smith also read a letter from Mr. W. S. Fitch, of Ipswich, enclosing a notice of this discovery from Mr. Goddard Johnson, of Norwich. Mr. Smith remarked that these communications afforded an exemplification of the utility of the Association, in the fact of three members having thus interested themselves so promptly in making a report of this discovery.

Mr. W. Sidney Gibson, of Tynemouth, informed the Committee that the report published in the 'Times' respecting the contemplated destruction of the remains of Berwick Castle, to make way for a terminus to the North British Railway, is not strictly correct.

Mr. G. Godwin communicated the substance of his remarks made in the Architectural section at Canterbury, on the masons' marks he had observed in many of the stones in the walls of Canterbury Cathedral. These marks appear to have been made simply to distinguish the work of different individuals, (the same is done at this time in all large works), but the circumstance that although found in different countries, and on works of very different age, they are in numerous cases the same, and that many are religious and symbolical, and are still used in modern free-masonry, led him to infer that they were used by system, and that the system was the same in England, Germany, and France.

In Canterbury Cathedral there is a great variety of these marks, including many seen elsewhere in various parts of Europe. They occur both in the oldest part of the crypt, the eastern transept (north and south), and the nave. The wall of the north aisle of the latter is covered with them, and here the stones are seen in many cases to have two marks, as in the cut: perhaps that of the  overseer, in addition to that of the mason, as the former (the N. shaped mark in this ease) appears in connexion with variousother marks in other places. In the nave the marks are from 1 inch to 11/2 inch long; in the earlier parts of the building they are larger and more coarsely formed[1].

overseer, in addition to that of the mason, as the former (the N. shaped mark in this ease) appears in connexion with variousother marks in other places. In the nave the marks are from 1 inch to 11/2 inch long; in the earlier parts of the building they are larger and more coarsely formed[1].

October 9.

Mr. Way exhibited several carefully detailed drawings, representing a stone cross, which is to be seen on the shores of Lough Neagh; they were executed by Thomas Oldham, Esq., of Dublin, who communicated the following account of this remarkable piece of sculpture.

"As far as I know, you have not in England any thing of equal beauty. Here these stone crosses are abundant; that at Arboe, of which I send the drawings, is situated on a small projecting point on the western shore of Lough Neagh, in the county of Tyrone, and being in a district hut little frequented, is less known than many others. Whether we consider its situation, or its intrinsic beauty of pro- portion and elaborate ornaments, it is a splendid monument of the good taste and piety of the times in which it was erected. It is close to the old church of Arboe, near which is also the ruin of an ecclesiastical establishment or college, which, tradition says, was very famous. The cross itself is formed of four separate pieces; the base or plinth, of two steps; the main portion of the shaft, a rectangle of 18 inches by 12 inches; the cross, and the mitre, or capping stone. These pieces are let into each other by a mortice and tenon-joint. The total height from the ground, as it stands, is 21 feet 2 inches. The material is a fine grit, or sandstone. The subjects of the sculptured compartments appear to be all scriptural: Adam and Eve, the garden of Eden, the sacrifice of Isaac, the Crucifixion," &c. Mr. Way observed that the early sculptured crosses which exist in various parts of the realm deserve more careful investigation than has hitherto been bestowed upon them. The curious group of these crosses at Sandbach, in Cheshire, affords a remarkable example, of which a representation may be found in Ormerod's History of that county; a singular and very ancient shaft of a cross on the south side of Wolverhampton church, Staffordshire, merits notice. Several crosses, most elaborately decorated with fretted and interlaced work, are to be found in South Wales; some of them bear inscriptions, which might probably serve as evidence of the period, or intention, with which they were erected. Those which best deserve observation exist at Carew, and Nevern, in Pembrokeshire; Margam, Porthkerry, and Llantwit Mayor, in Glamorganshire; and not less curious examples are to be seen in the North of the Principality; at Tremeirchion, Holywell, and Diserth, in Flintshire. Mr. Way shewed also some sketches, recently taken by him, of the ornamental sculpture on a stone cross, and  portions of two others, existing at the little clmrch of Penally, near Tenby. One perfect cross remains erect in the churchyard; two portions of a second were found employed as jambs of the fire-place in the vestry; these, by permission of the vicar, the Rev. John Hughes, were taken out, and one of them was found to he thus inscribed, Hec est crux quam ædifieanit meil domne. . . A large portion of the shaft of the third, most curiously sculptured on each of its four sides, was extricated from concealment under a gallery at the west end of the church, and it will be placed in a suitable position in the church-yard. It had been noticed by some writers as the coffin, according to local tradition, of a British prince. By comparison with the curious sculpture of the twelfth century, noticed by Mr. Wright in his account of Shobdon church, Mr. Way conjectures that possibly these crosses may have been reared at the period of Archbishop Baldwin's Mission, in 1187, but some of the ornaments appear to bear an earlier character.

portions of two others, existing at the little clmrch of Penally, near Tenby. One perfect cross remains erect in the churchyard; two portions of a second were found employed as jambs of the fire-place in the vestry; these, by permission of the vicar, the Rev. John Hughes, were taken out, and one of them was found to he thus inscribed, Hec est crux quam ædifieanit meil domne. . . A large portion of the shaft of the third, most curiously sculptured on each of its four sides, was extricated from concealment under a gallery at the west end of the church, and it will be placed in a suitable position in the church-yard. It had been noticed by some writers as the coffin, according to local tradition, of a British prince. By comparison with the curious sculpture of the twelfth century, noticed by Mr. Wright in his account of Shobdon church, Mr. Way conjectures that possibly these crosses may have been reared at the period of Archbishop Baldwin's Mission, in 1187, but some of the ornaments appear to bear an earlier character.

Mr. George White, of St. Edmund's College, Old Hall Green, Herts, communicated the following note on the emblems of saints.

"I perceive with great pleasure that the interesting subject of the emblems of saints will again be brought forward by the Society; I beg to supply a few omissions and corrections of the article which appeared in the first number of the Archæological Journal.

Page 57. After "St. Waltheof," read Aug. 3.

Page 59. St. Henry VI. K. this is a mistake; Henry VI., though held in great veneration by his subjects, has never been canonized or added to the number of the saints. The mistake may have arisen from his name occurring on the day of his death (May 22.) in the Sarum Missal. But this was only the case with those printed in Henry the Seventh's reign, in order that mass might be recited for the repose of his soul.

Ibid. After "St. Withburga," read July 19.

Page 60. The ladder was an emblem of perfection, portraying the various steps by which the soul arrived at perfection. This figure is taken from Jacobs dream. It was also one of the emblems of our Saviour's passion.

Page 61. After St. Wolstan, read May 30.

Ibid. After St. Wendelin, read Oct. 20.

Page 63. Instead of "Seven cardinal virtues," read "Three theological virtues, Faith, Hope, and Charity; and four cardinal virtues. Justice, Prudence, Temperance, and Fortitude."

Ibid. "Seven Mortal," read "Seven Deadly.

Page 63. For "Accedia" misspelt for "Accidia," read "Sloth."

Mr. Goddard Johnson forwarded some further particulars relative to the discovery at Felmingham. He writes, "Among the objects discovered is a line head of the Emperor Valerian, 61/2 inches high; a head of Minerva 41/4 inches high; a beautiful figure of a cup-bearer, 3 inches high, dressed in a tunic and buskins; all these are in bronze. There are many other articles the names of which I do not know, but I shortly hope to be able to send lithographic representations of all of them, together with full particulars of the discovery. I may add there were two or three coins, one of which in base silver is of Valerian."

The Rev. Dr. Buckland informed the Committee that he was about to prosecute his researches into the Roman remains near Weymouth, an account of which he had laid before the Association at Canterbury. He and the Rev. W. D. Conybeare had visited the site, and found abundant evidence confirmatory of extensive subterranean works. They had already uncovered the angles of a building, some curious walls, and the corner of a pavement. It appears that in the time of George the Third a large tessellated pavement was discovered at the spot, which was excavated at the cost of the king, who had it covered up again.

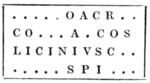

Mr. Smith exhibited drawings of three inscribed votive altars forwarded by Mr. Joseph Fairless, of Hexham, and read the following note from that gentleman:—

"The three rough sketches are of Roman altars, found at Rutehester, a week or two ago; this is the fourth station on the line of the Roman wall westward from Newcastle. There were five altars turned up, lying near the surface of the soil, outside the southern wall of the station. The three altars delineated are in excellent preservation; one of the others appears to be dedicated likewise to the sun, but the inscription is nearly obliterated. The last is smaller, about 2 feet high, without any apparent inscription. With regret I add, that a statue likewise found was broken up, for the purpose of covering a drain by the labourers employed; timely intervention saved the altars."

|

1. Within a wreath the word deo; beneath |

2. deo soli invic |

3. deo invicto |

No. 2. of these inscriptions informs us that a temple of the Roman station which had from some cause become dilapidated, had been restored by the Prefect Cornelius Antonius, and the dedications on Nos. 2. and 3. shew that it was a temple erected to the Sun or Mythras, which deity is implied in the word deo on No. 1, a votive altar, the gift of a soldier of the sixth legion, named L. Sentius Castus. The altars are probably as late as the middle of the third century, or later.

Mr. Smith also exhibited a drawing forwarded by Mr. Parker, of a sccatta, the property of the Rev. G. M. Nelson, of Boddicot Grange, near Banbury, and observed that it was an unpublished specimen, and extremely interesting, as shewing in a striking manner the way in which the early Saxons copied the Roman coins, then the chief currency of the country. Without comparing this with the prototype, it would he impossible to conjecture what the artist had intended to represent, but by referring to the common gold coins of Valentinian, it will be seen that the grotesque objects upon the reverse of the Saxon coin are derived from the seated imperial figures on the Roman 'aureus,' behind which stands a Victory with expanded wings. This practice of imitation is strikingly exemplified by the accompanying cuts kindly furnished by the Council of the Numismatic Society. The joined cuts represent the obverse and reverse of a coin of Civlwlf, King of Mercia, A.D. 874; the other is the reverse of a gold coin of Valentinian. Mr. Hawkins, who has published this coin in his paper on the "Coins and Treasure found in Cuerdale," observes: "The diadem and dress of the king is, like that of many other Saxon kings, copied from those of the later Roman emperors: but a reverse upon an indisputably genuine coin, so clearly copied from a Roman type, has not before appeared[2]." The inscription on the reverse of the penny of Civlwlf is ealdovvlf. menta. for Ealdwlf Monetarius.

Mr. Smith also exhibited a drawing forwarded by Mr. Parker, of a sccatta, the property of the Rev. G. M. Nelson, of Boddicot Grange, near Banbury, and observed that it was an unpublished specimen, and extremely interesting, as shewing in a striking manner the way in which the early Saxons copied the Roman coins, then the chief currency of the country. Without comparing this with the prototype, it would he impossible to conjecture what the artist had intended to represent, but by referring to the common gold coins of Valentinian, it will be seen that the grotesque objects upon the reverse of the Saxon coin are derived from the seated imperial figures on the Roman 'aureus,' behind which stands a Victory with expanded wings. This practice of imitation is strikingly exemplified by the accompanying cuts kindly furnished by the Council of the Numismatic Society. The joined cuts represent the obverse and reverse of a coin of Civlwlf, King of Mercia, A.D. 874; the other is the reverse of a gold coin of Valentinian. Mr. Hawkins, who has published this coin in his paper on the "Coins and Treasure found in Cuerdale," observes: "The diadem and dress of the king is, like that of many other Saxon kings, copied from those of the later Roman emperors: but a reverse upon an indisputably genuine coin, so clearly copied from a Roman type, has not before appeared[2]." The inscription on the reverse of the penny of Civlwlf is ealdovvlf. menta. for Ealdwlf Monetarius.

A letter was read from Archdeacon King, acknowledging the receipt of a letter from the Secretary, and a copy of the "resolution" passed at Canterbury, relative to the paintings in East Wickham church, and stating that he had, immediately upon the receipt of the letter, requested information upon the matter from the minister and churchwardens.

A letter was read from Messrs. Hodges and Smith, of Dublin, to Lord Albert Conyngham, on an account attached to the genealogy of the Waller family, under the name of "Richard Waller" upon a roll dated 1625, which refers to the building of Groombridge House in the county of Kent, for Richard Waller, by the Duke of Orleans, taken prisoner by him at the battle of Agincourt.

Upon the suggestion of the Rev. J. B. Deane, it was resolved, that the Committee authorize their secretary, Mr. Smith, to visit, inspect, and report upon some remains on the site of a supposed Roman villa on Lanham Down, near Alresford, Hants, with a view to enable the Hon. Col. Mainwaring Ellenker Onslow to form an opinion respecting the probable success of an excavation on an extended scale about to be undertaken, if advised, by that gentleman.

Mr. Wright read a communication from the Rev. Lambert B. Larking, who stated that "a few weeks since some labourers, in digging for gravel on the hill above the manor-house of Leckhampton, about two miles from Cheltenham, suddenly came upon a skeleton, in a bank at the side of the high-road leading from Cheltenham to Bath. It was lying doubled up about 3 feet under the surface; it was quite perfect, not even a tooth wanting. On the skull, fitting as closely as if moulded to it, was the frame of a cap, consisting of a circular hoop, with two curved bars crossing each other in a knob at the top of the head. This knob, finishing in a ring, seems to have been intended for a feather, or some such military ensign. The rim at the base is nearly a perfect circle, and the bars are curved, so that the entire framework is itself globular. The bars are made apparently of some mixed metal, brass fused with a purer one; they are thin and pliable, and grooved; the knob and ring are brass, covered with verdigris, while the bars are smooth and free from rust. When first found, there was a complete chin chain, of this only three links remain, those next the cap very much worn. The skull is tinged at the top with green, from the pressure of the metal, and in other parts blackened, as though the main material of the cap had been felt, and the bars added to stiffen it. They are hardly calculated from their slightness to resist a sword cut, but the furrowed surface gives them a finish and proves that they must have been outside the felt. Nothing else whatever was found. A black tinge was distinctly traceable all round the earth in which the body lay." A Roman camp rises immediately over the spot where this relic was found, and large traces of Roman interment are found within a hundred yards of it.

October 23.

Mr. C. R. Smith, referring to the minute of the proceedings of the Central Committee on October 9th, stated, that in compliance with the request of the Committee he had visited the site of the Roman remains at Bighton, in Hampshire, and in the following report detailed the result of his examination of them:—

"The field in which indications of Roman buildings had been noticed is called Bighton Woodshot, and is situate in the parish of Old Alresford, on the border of the parish of Bighton, within the district of Lanham Down. Until within about ten or twelve years, that portion of the field occupied by the buildings was a waste tract covered with bushes and brushwood. It is now arable land, but in consequence of the foundations of the buildings being so near the surface, is but of little worth to the agriculturist. Some years since many loads of flints and stones were carted away as building materials from the lower part of the field, when it is probable some portion of the foundations may have been destroyed, as the labourers state they found walls and rooms which, from their being roughly paved, and containing bones of horses, they supposed were the stables. From irregularities in the surface of the ground, as well as from vast quantities of flints and broken tiles, the foundations appear to extend over a space of, at least, one hundred square yards. Across about one half of this area, I directed two labourers to cut two transverse trenches, and ordered them to follow out the course of such walls as they might find, and lay them open without excavating any of the enclosed parts. The Rev. George Deane, the Rev. W. J. E. Rooke, and the Rev. Brymer Belcher, from time to time attended the excavations, and afforded me much assistance.

"In the course of a week's labour we have laid bare the walls of two rooms, each measuring 15 paces by 61/2, and distant from each other about 20 paces; an octagonal room distant 26 paces from the nearer of the other rooms, and measuring 9 paces across; portions of a wall near the octagonal room, and of one about 20 paces in another direction. The walls of the octagonal room are constructed of flints, and coped with stone resembling the Selbourne stone; those of one of the long rooms are of flints coped with red tiles. The mortar in all is of a very inferior description, and in a state so decomposed, that in no instance have I found it adhering either to the flints of the walls or to the tiles, which have been used in the buildings.

"It would be premature upon such a very partial and superficial investigation, to predict what may be expected to be discovered should these extensive foundations be thoroughly examined; but it may be reasonably expected that several more apartments would be easily met with adjoining those already indicated by the recent excavations. It is possible that some may contain tessellated pavements, although the floor of one of the rooms, as far as we could ascertain, is unpaved; others as yet unexamined may be of a superior description, as vestiges of painted wall, flue and hypocaust tiles, would lead us to suppose. The splendid tessellated pavements found at Bramdean eight miles distant, at Thruxton, and in other parts of the county of Hants, afford additional inducement to any authorized individual to carry on the researches I have commenced by the wish of the Committee, especially when it is considered that the loose building materials would alone repay the trifling expense incurred, and that the land would be materially improved by the removal of the masses of fallen masonry which at present prevent its cultivation. In the same field is a barrow bearing the significant appellation of Borough-shot."

Mr. Smith then stated that he had visited and inspected Carisbrook Castle, in the Isle of Wight, which is in a sad state of dilapidation, and apparently going fast to utter decay and ruin, for the want of proper precaution being taken to hinder visitors and others from wantonly destroying the walls and buildings.

Mr. Thomas King, of Chichester, forwarded drawings of some Egyptian antiquities in the museum of that town, and the Rev. T. Beauchamp presented four lithograph drawings illustrative of Buckenham Ferry church.

November 13.

Mons. Lecointre-Dupont presented through Mr. C. R. Smith: 1. Projet de Cartes Historiques et Monumentales. Poitiers, 1839. 2. Histoire des rois et des dues d'Aquitaine par Mm. de la Fontenelle de Vaudoré et Dufour. 3. Notice sur deux tiers de sol d'or Mérovingiens, et Note sur un denier de Catherine de Foix, par M. Lecointre-Dupont. Mons. de Caumont presented through Dr. Bromet:—1. Inspection des Monuments Historiques; par M. De Caumont, 8vo. Caen, 1844. 2. Rapport Verbal sur les Antiquités de Treves et de Mayence; par M. de Caumont, 8vo. Caen, 1843.

Mr. Wright read a letter from W. H. Gomonde, Esq., of Cheltenham, announcing the formation of a branch Committee of the Archæological Association at that place for the county of Gloucester, of which Mr. Gomonde had been chosen chairman, and Mr. H. Davies had consented to act as secretary. Good service is to be expected from the exertions of this committee, and the formation of such branch committees in different parts of the country cannot be too strongly recommended.

Mr. Wright at the same time exhibited an electro typed impression, forwarded by Mr. Gomonde, of a gold British coin found at Rodmarton. It is one of those hitherto attributed to Boadicea. (See Ruding, fig. 3. pl.29.) Mr. Gomonde questions the correctness of this appropriation, and suggests the probability of the inscription bodvo referring to the Boduni.

Mr. Way laid before the Committee the following instances of impending desecration:—

"St. John's church, near Laughton le Morthen, Worksop, Yorkshire, having ceased to be of utility as a place of worship for the parishioners, and used only at present on the occasion of funerals in the adjacent cemetery, is to be left to fall into decay, and is now in a state of great dilapidation. The vicar is the Rev. J. Hartley. Mr. Galley Knight has great influence in that part of the country. The Trinity College Kirk, Edinburgh, is condemned to be demolished, to accommodate the projectors of a railway, in the line of which it chances to be placed. The town council have been in vain petitioned on the subject. The few remaining traces of Berwick Castle are also condemned, to suit the convenience of a railway company. However inconsiderable the fragments of construction may be which mark the site of this border fortress, they surely deserve to be preserved, as a memorial of no small historical interest. At all events these kind of "vandal" acts should be brought under the notice of the public in our Journal, as statements made at the Committee meetings." Mr. Way also stated that the Rev. George Osborne, of Coleshill, Warwickshire, reports the discovery of a small brass in the church at that place, which is now detached from its slab, but the indent to which it appertains appears in the pavement of the chancel, and the brass will shortly be replaced." This brass appears to be mentioned by Dugdale, in his detailed account of sepulchral memorials at Coleshill, as Alice Clifton, widow of Robert Clifton; she died in 1500. It represents a lady, temp. Hen. VII., she wears the pedimental fashioned head-dress, with long lappets, the close fitting gown of the period with tight sleeves, which terminate in a kind of wide cuff, by which the hands are covered excepting the fingers, so as to have the appearance of mittens. Her girdle falls low on the hips, being fastened in front with two roses, from which depends a chain with an ornament at the extremity in the form of a large bud, or flower, of goldsmiths' work, which served to contain a pastille, or pomander, according to the fashion of the sixteenth century, esteemed as a preservative against poison." Numerous detached sepulchral brasses exist in parish churches in the country, and almost every year we hear of one or more which for want of being secured in time, are mislaid and lost.

Dr. Bromet remarked that some brasses commemorative of the family of Mauleverer, have been within a few years removed from a stone in the chancel of St. John's church near Laughton le Morthen.

Mr. Smith, in reference to the destruction of ancient remains by railway projectors, observed, that the directors of the Lancaster and Carlisle railway were about to carry their line through and destroy one of the few Celtic monuments remaining in this country. It consists of thirteen large stones of Shap granite, and is situated in a field the property of the Earl of Lonsdale on the road from Kendal to Shap, and about two miles from the latter place[3]. The attention of the Earl of Lonsdale has been drawn to the circumstances in which this ancient monument is placed, with a view to effect its preservation.

Mr. Wright observed that it was very desirable that the Committee should keep a watchful eye on the progress of the numerous railways lately projected. During the progress of excavating, many remains of antiquity had already been destroyed, and although some articles had found their way into private collections, no exact account had in most cases been preserved of the position and circumstances of their discovery. If the monument alluded to by Mr. Smith must be destroyed, it is to be wished at least that some intelligent observer should be present to note down any discoveries which may be made. Mr. Wright had heard that antiquities had been recently discovered in excavating for the Margate and Ramsgate railway, but could not learn what they were or what had become of them.

Mr. Smith exhibited a sketch of some early masonry in the cellar of a house in Leicester, forwarded by Mr. James Thompson, with the following letter:—

"On September 28, Mr. Flower of this town was informed by the sexton of St. Martin's church, that there were some curious arches in a cellar in his occupation. Mr. Flower was sketching some Norman arches in the belfry of the church, at the time, which, the sexton said, reminded him of those in his cellar. In the evening Mr. F. visited the place in company with a few friends, and was so much struck with the remains, that he bestowed considerable examination upon them, and took a rough sketch on the spot. I should state that the house under which the cellar is situated is an old one, it has rather a large projecting gable, and is probably of the date of Queen Elizabeth's reign. The masonry of the wall in the cellar is composed mainly of rough irregular-shaped pieces of stone, principally granite, which are laid together in convenient portions, but not in regular rows. Over the heads of the arches, intended to be round, are rows of tiles, which are similar in shape to those used in the Jewry wall, and which, as you will perceive, resemble those to be met with in remains of Roman origin. There are also, in various parts of the wall, other bricks of the same shape, but not laid in order.

"The following are the measurements of the openings: from the top to the bottom of the first arch on the left hand, 48 inches; width, 22 inches. Width of the opening in the recessed part, 8 inches. This was the entire width of the actual opening. The depth of the splaying is 23 inches, leaving 12 inches on the outer side, which is not to be seen, as there is nothing but earth-work beyond: the entire thickness of the wall is however 35 inches, from which the extent of the splaying outwardly is inferred. From the angle at the base of the outer orifice to that of the inner (on the cellar side) is 25 inches; from the base of one to the base of the other is 23 inches; thus, the second arch is on the surface of the wall, 44 inches high, 22 wide; the third, 501/2 inches by 22; and the fourth, (on the right of the picture, and filled up with rubbish,) 50 inches by 24.

"The following are the measurements of the openings: from the top to the bottom of the first arch on the left hand, 48 inches; width, 22 inches. Width of the opening in the recessed part, 8 inches. This was the entire width of the actual opening. The depth of the splaying is 23 inches, leaving 12 inches on the outer side, which is not to be seen, as there is nothing but earth-work beyond: the entire thickness of the wall is however 35 inches, from which the extent of the splaying outwardly is inferred. From the angle at the base of the outer orifice to that of the inner (on the cellar side) is 25 inches; from the base of one to the base of the other is 23 inches; thus, the second arch is on the surface of the wall, 44 inches high, 22 wide; the third, 501/2 inches by 22; and the fourth, (on the right of the picture, and filled up with rubbish,) 50 inches by 24.

"On the opposite side of the cellar, that is, the eastern one, are four square recesses, which are situated 2 feet 10 inches above the floor, and in a line nearly corresponding in position with the arches on the other side. They are 15 inches wide by 10 deep; from the surface of the wall to the back of each recess is 11 inches. The bottom of each recess has been covered with a large tile. There are three hollows, of less size and irregular shape, higher up in the wall, but they may have been made by accident. On measuring the dimensions of the cellar, I found them to be as follows: length from north to south, 9 yards 29 inches; breadth from east to west, 4 yards 32 inches. It is almost exactly two cubes. The height I forgot to measure, but think it is nearly three yards. The thickness of the wall on its south side is at least 38 inches. The floor of the cellar is about 6 feet below the level of the street. I have forgot to mention, that the arches are divided by a space of from 29 to 32 inches. Thus far I have given you the facts; conjectures about the origin of this singular and (to me) mysterious remain, I leave to be made by your better-informed friends.

"I may add, that the street in which the relic was discovered, is called Town-hall-lane. Formerly, I learn, it was known as Holyrood-lane, and the neighbouring church, now St. Martin's, was designated St. Cross. The Town-hall, a building of the Elizabethan era, is nearly opposite—its western extremity is exactly opposite the old house under which the cellar is situated.

"The original level of the ground (before the made earth had accumulated) would not, it seems to me, have been less in depth than that which lies between the level of the street and the floor of the cellar. In some parts of the town the made earth lies much deeper than six or seven feet."

November 13.

Mr. John Dennett, of New Village, Isle of Wight, presented, through Mr. Smith, a rubbing of a sepulchral brass of a knight of the fourteenth century, in Calbourne church. Isle of Wight. "The brass," Mr. Dennett states, "has been broken in several places, and is badly embedded in a new stone, very uneven; in some places it is above, and in others considerably below, the surface of the stone. It is no longer in its original place, having been removed during the late rebuilding of the church. It was in a slab of Purbeck marble, which covered an altar-tomb close to the south transept, which has been pulled down, and the tomb in consequence destroyed. It seems that an inscription and date was cut on the marble, but not a fragment of the slab is to be found. The effigies probably represents one of the Montacutes, carls of Salisbury, the ancient possessors of Calbourne, from a female descendant of whom the property came by marriage to the Barrington family." Mr. Smith observed that Mr. J. G. Waller, editor of the "Monumental Brasses," from a peculiarity in the execution of this brass, as well as from a striking resemblance of features, believes it to have been engraved by the same artist as one in Harrow church, Middlesex, to the memory of John Flambard, and another to the memory of Robert Grey, at Rotherfield Greys, Oxfordshire: the latter bears the date of 1387.

Mr. W. H. Brooke, of Hastings, exhibited a drawing of a monumental brass just discovered beneath the flooring of the second corporation-pew in the chancel of All Saints church, Hastings. It represents a burgess and his wife, the figures being two feet one inch in length. Above them is the word Ehesus in an encircled quatrefoil, and beneath an inscription:—"Here under thys ston lyeth the bodys of Thomas Goodenouth somtyme burges of thys towne and Margaret his wyf of whose soules of your charite say a pater noster and a ave." There is no date, but from the costume of the figures this monument may be assigned to the latter part of the fifteenth century.

Sir Henry Ellis communicated a document from a chartulary of the priory of Carisbrook, relating to the founding and dedication of Chale church, in the Isle of Wight. Sir Henry remarked that the late Sir Richard Worsley possessed another register of the deeds of Carisbrook priory, from which, in his "History of the Isle of Wight," 4to. 1781, p. 244, he gives the substance of this same instrument, but he could not have seen its importance for the present purpose, that of ascertaining with certainty the actual date of one of our old parochial churches, as he has omitted to give us its exact date, describing it merely as a deed of the time of Henry the First; and he has said nothing of the age, the structure, or even of the existence at the present time of a church at Chale. It was under this instrument that Chale was made a parish, separate from Carisbrook, and it is evident from it that no previous ecclesiastical structure existed at Chale, so that whatever features of the original architecture are still to be traced in Chale church, however few, they may be of use as tests for comparison in forming an opinion of the age of other parochial churches. Henry the First's was a reign in which many new parish churches were erected[4].

Mr. Smith read an extract from a letter from Mr. R. Weddell, of Berwick-upon-Tweed:—"I was recently at Gilsland, and from thence took several short trips to examine the Roman wall in the vicinity. At Caervoran not a vestige remains. The tenant has recently filled up the baths, &c., and the site of the camp is covered with potatos and turnips! Notwithstanding all that has been done and said, down to Hodgson, much remains for investigation, and I hope some of the Members of the Association will soon direct their steps to that district. At Caervoran I saw an inscription which I suspect has never been printed. It is on a stone with fluted sides, ornamented on the top with a vase, and reads At Burdoswald another stone has been recently found, but the inscription is much defaced, and part of the upper side has been lost. All I can make out of it is, The tenant also shewed me a small brass coin of the emperor Licinius, much defaced, which he lately found on his farm. The entrance to the camp through the west wall is distinctly seen, and about midway between it and the wall to the north are several large stones clasped together with iron rods. I have some other rough memoranda, which I shall hereafter write to you about, having previously compared them with Horseley's "Britannia Romana," and Hodgson's account of the Roman wall from Newcastle to Carlisle. The latter author (Part II. vol. iii. p. 201). exiv.) prints the dedication to the god Silvanus, now at Lanercost, correctly, but does not shew how the letters are placed, and omits to notice that in the last line the letter e is joined to the preceding n.The Rev. Brymer Belcher, of West Tisted, Alresford, Hants, communicated a notice of Roman remains at Wick, near Alton. It appears that many years since a portion of a field in which are vestiges of extensive buildings, was opened, when pavements and walls were discovered, and immediately broken up for repairing the roads, but Mr. Belcher says that the foundations of other buildings are still remaining and would well repay an excavation.

The Rev. E. G. Walford, of Chipping Warden, contributed a brief notice of the discovery of some stone coffins at Clalcombe Priory, Northamptonshire, the property of Mr. C. W. Martin, M.P., accompanied with a sketch of the most perfect specimen.

Mr. Joseph Jackson, of Settle, Yorkshire, presented through Mr. Smith, a lithograph of a Norman font, lately rescued from obscurity in Ingleton church. Mr. Jackson reports that a font of beautiful workmanship is lying unnoticed and nearly covered with grass in Kirkby-Malhamdale church-yard. It is used for mixing up lime for whitewash, with which the arches and pillars of the church are periodically bedaubed. The repeated application of the whitewash has however not yet entirely obscured all traces of their elaborate workmanship.

Mr. John Adey Repton communicated notices of discoveries of three skeletons, and weapons or instruments in iron, much corroded, on the site of an ancient camp at Witham called Temple Field, and of urns containing bones and ashes in a field at the east end of the town of Witham. The former were discovered in cutting the railway, the latter were turned up by the plough. A map and drawings were exhibited in illustration. The urns were so much broken by the plough, that out of the fragments of six different specimens, Mr. Repton and Mr. W. Lucas (who assisted in the examination) were able only to form a single one. It is sixteen inches high, ten inches in diameter at the top and seven at the bottom, in colour a light gray, with a raised indented rim, about three inches from the mouth. The other fragments are of a dingy red and brown black, and are mostly stamped with circular and triangular holes. The urns have been worked by hand and are rudely executed; the clay of which they are composed is mixed with small white stones and bits of chalk.

A letter was read from the Rev. Arthur Hussey, of Rottingdean, on peculiarities of architecture in the churches of Corhampton, Warnford, and East Tisted, Hants. Although the quoining of Corhampton church consists not of Saxon "long and short work," but of large stones, such as appear in more modern edifices, the walls are sufficiently characterized as being Saxon by that peculiar kind of stone-ribbing which, having been depicted at page 26 of the Archæological Journal, does not require to be further described or remarked on than by stating that this peculiarity is yet in good preservation on all the walls of Corhampton church, except those of the eastern end of the chancel, which are of modern brick. The present entrance to this church is through the south wall, and at the same part where the former entrance is indicated to have been, by an arch with a short rib ascending from its crown to the wall-plate, similarly to a rib above a perfect arch opposite in the north wall; although this last does nut appear to have contained a doorway. In the south wall is a square stone, having at its angles a trefoil-like ornament, and engraved with a circle which incloses on its lower half some lines radiating from a central hole. This is said to be a consecration-stone, which, from its little elevation above the ground, it may have originally been, although its lines would lead us to infer that it has served also for a sun-dial. Corhampton church has no other tower than a modern wooden bell-turret at its west end, above an original window divided by a rude oval balustre. The chancel-arch, also rude, springs from impost-like capitals, and is of depressed segmental shape. A stone elbow-chair, formerly occupying part of the altar-steps, has lately been placed within the altar-rails; and in the chancel pavement is a rough irregularly oblong-stone, rudely incised towards its angles with crosses, denoting it to have been the altar-stone.

The Norman church at Warnford is a long plain edifice, comprising a chancel, a nave, a west tower, and a south porch. Its walls, being very thick, appear still to be in excellent condition, although the church is rendered damp by trees which closely surround it. The chancel and nave, being of equal breadth and height, are externally distinguished only by the juxtaposition of two of the roof-corbels. The tower is square, and from certain marks on its north and south sides, is probably older than the nave; but it possesses nothing of Saxon character except, as at Barton and Barnack, the absence of an original staircase; unless, perhaps, originality may be due to the existing stairs, composed of triangular blocks of oak, fastened to ascending beams supported by carved posts, and a semicircularly recessed landing-place in the south-eastern corner of the wall. The upper part of the tower has been repaired with brick, but its belfry-windows, two on each face, are original large circular holes, splayed inwardly and lined with ashlar. The porch and inner doorway are of a pointed style. Inserted in the north wall, one within and one without the church, are two small stones with inscriptions, evidently of great antiquity; but the letters, partly illegible from age, are wholly so, except to those conversant with ancient characters. Against the south wall is a consecration-stone, precisely similar to that of Corhampton, but in better preservation, it having been secluded from the weather by the porch. The present east window is an insertion of the fourteenth century, but on the inside of the east wall is a large arch, which probably contained windows corresponding to the Norman windows in the side walls. The ceiling is flat and modern, but some roof- brackets and corbels below it indicate that the ancient roof-timbers may probably remain. This church is sadly disfigured by high pews and a huge monument at its east end.

At East Tisted, Mr. Hussey saw a hagioscope with openings in the Perpendicular style; but as a new church is there in course of elevation, this interesting ecclesiastical feature is now, probably, no more.

Dr. Bromet observed that in one part of this communication, Mr. Hussey seemed to doubt whether Corhampton church may not have been restored since Saxon times, with some of the materials, and on the plan, of a preceding Saxon edifice. But such doubts, he thought, are not admissible; for otherwise they might be applied to every church without a recorded date. Considering it, therefore, as really Saxon, he thought that this church is a monument peculiarly valuable; our few other Saxon ecclesiastical remains being only towers, doorways, or smaller portions of buildings.

Mr. Thomas Inskip, of Shefford, Beds, communicated an account of Roman remains found a few years since in the vicinity of that town. It appears that for a long time this locality has been productive of vast quantities of interesting objects of art, of the Romano-British epoch, most of which, discovered previous to Mr. Inskip's researches, have been either lost or dispersed. "Roman vaults have been emptied of their contents, vases of the most elegant forms and the finest texture have been doomed to destruction for amusement, and set up as marks for ignorance and stupidity to pelt at. In another direction, I have known a most beautiful and highly ornamented urn with a portrait and an inscription on its sides stand peaceably on the shelf of its discoverer, till being seized with a lit of superstitious terror lest the possession of so heathenish an object might blight his corn or bring a murrain amongst his cattle, he ordered his wife to thrust it upon the dunghill, where it perished." Mr. Inskip's descriptive narrative proceeds as follows:—

"A similar fate inevitably awaited the relics found at Shefford, and in its immediate neighbourhood at Stanford-Bury, had not he who now records their escape been the humble instrument of their preservation. Indeed a number might have been destroyed previous to my becoming acquainted with their existence, the earliest intimation of which arose from a denarius having been carted with gravel from a neighbouring pit, and laid in the public road; it was afterwards picked up and brought to me for sale; this led me to inspect the scene of operation, and to watch and assist in future discoveries. The first objects of gratification were two large dishes of the reputed Samian ware, one of which is ten inches in diameter, radiated in the centre, and having the maker's name crossing it. The other was a beautiful specimen, with horizontal handles, and ornamented with the usual pattern round the edge. The larger dish of the two is doubtless the lanx, as its large size, and the prefix to the maker's name, sufficiently indicates—offager.

"Some time after, a Roman urn, surrounded by eleven Samian vases, was discovered, most of which were in a perfect state. A great quantity of broken glass also was found here, together with a whitish-coloured bottle of earthen manufacture.

"A fresh supply was subsequently found of terra cotta vases, somewhat larger than an ordinary sized tea-cup, with various names impressed across their centres; also a great quantity of greenish-coloured glass, but too much mutilated to admit of restoration. The bottom of one of these glass vases is round, eight inches in diameter, remarkably thick, and wrought in concentric circles; the neck and mouth are three and a half inches in width; the handle being of much thicker substance is preserved entire, and is exquisitely wrought into the device of a fish's tail.

"At the same time and place was found a brass dish or pan, which one of the labourers, suspecting to contain money, wrenched to pieces in his eagerness to secure it. This was greatly to be regretted, as the form of this vessel was of a high order of taste; but with much patience I have succeeded in restoring it to its primitive shape. On one side is a looped handle, the top of which, representing an open-jawed lion's head, is joined to the upper rim; on the opposite side protrudes a straight handle, terminating with the head of a ram; the bottom is turned in beautiful concentric circles, and has still adhering to its inside (however strange it may appear to the sceptical) a portion of its original contents. A similar vase was found at the opening of Bartlow hills in 1835, which has but one handle and is far inferior in point of elegance; a drawing of it is given in the Archæologia. A coin of first brass was lying close by, much corroded, bearing on the obverse an imperial head, though not corronated or laureated; on the reverse a faint impression of a Roman altar. Not far from these was found an iron stand or case for holding a lamp. Another coin of third brass in fine preservation, and covered with a beautiful patina, was found on this spot.

"Afterwards, when digging by myself, I struck my spade on a large amphora, and added many fractures to those it had received; by cementing it together, I soon restored its original shape and dimensions. It has two handles, its height exactly two feet, and its broadest diameter eighteen inches. Near to this amphora were placed three terra cotta vases of great beauty, ornamented round their margins with the usual leaf of the laurel or the lotus, or whatever else it may hereafter be determined to be. These were taken from the earth without the slightest injury, and are still perfect as when first made.

"A beautiful glass vase was the companion to these,—its size double that of a modern sugar basin, it is radiated with projecting ribs, its shape is nearly globular, it has no handles, is of a fine pale amber colour, and was doubtless used for a funereal purpose.

"A small glass funnel was found here, which is restored from fragments to its original shape. A lachrymatory, or unguentarium, was lying near, but too much mutilated to invite an attempt to mend it. On one side of the vault, and close to one of the vases, a hole had been scooped in the earth, in which was deposited a quart or perhaps three pints of seeds, charred, and still perfectly black; through the dryness of the soil they had been admirably preserved.

"At a small distance from the three beautiful vases last mentioned, was dis- covered a quantity of blue glass, which from the newness of the fractures I concluded had been just broken by the spade. I collected the pieces, and cementing them together, they formed a beautiful jug or ewer, the shape of which is the most chastely elegant that taste could design or art execute. Its graceful neck and handle, its beautiful purple colour, and the exquisite curl of its lips, so formed to prevent the spilling of the fluid, proclaim it to be one of the most splendid remains of antiquity. It is radiated longitudinally, and unites great boldness of design with delicacy of execution. In contemplating this precious relic we feel that time and a reverence for taste and antiquity, have given to it a much more sacred character than the pagan rites it may have assisted to administer. At various times numbers of Samian vases were disinterred from this spot, amounting to more than three dozen, and of great varieties of shapes; the names impressed across several were maccivs—calvinvs—lvppa—tenevm—silenvs—liberalis—silvvs—ofcoet, &c. &c.

"The ground in which the foregoing relics were discovered, like many other places of Roman sepulture, was by the way side, lying on the Iknield road in a straight line between Dunstable and Baldock, not indeed on the main street which passes through the Ichniel ford, but (as I judge) on a vicinal way, for which opinion there is strong presumption, from its passing so near to the old military station at Stanford Bury, and which road Salmon has traced as far as Cainho, from whence he says it went on to Baldock; if so, it doubtless passed through Shefford, and close by the very spot where these relics were discovered. This burial ground forms three sides of a square, which has originally been enclosed with a wall of sandstone from the neighbouring quarry; the foundation may be easily traced at the depth of three feet, the present high road forming the fourth side of the square. The depth of these deposits was about three feet from the earth's surface.

"That the whole of this inclosure contained the ashes of persons of distinction, may be inferred from the great beauty and value of the relics interred with them; some of these are of the most sacred character, such for instance as the bronze acena or incense pan, the blue jug or simpulum, and a sacrificial knife found with them. All of these implements belong to the priestly office, the two last of which, with the cyathus, are frequently seen on the reverses of Roman coins, indicating the union of the imperial and pontifical dignity.

"A considerable time elapsed after the before-mentioned discoveries, when I conjectured from the official uses and purposes of many of the remains themselves, the probability of finding a place of pagan worship in their immediate vicinity. I commenced a search accordingly. After much labour and patience, I found the site of a Roman building at the distance of about half a furlong from the cemetery, and by digging round it, ascertained it to occupy an area of thirty feet by twenty, round which, about the foundation, was deposited a great quantity of mutilated remains of Samian pottery, and other coarse ware, most of the latter having probably been manufactured from the earth of a contiguous spot, which for ages, and to this day retains the name of 'Oman's Pond.' The clay dug from hence is well adapted for the purpose of making such articles, and I have no doubt a pottery once formed a part of the site of this (R)oman's pond. This success induced me to try once more the old scene of my labours. By digging round the outside of the cemetery, I found a silver trumpet, of very diminutive size, being only sixteen inches in length; also a curious iron instrument, used as I presume to fasten the nails and pick the hoofs of the horse whose rider's ashes reposed with his bones in this place. Here was formed a trench or cist, about twelve feet in length, filled with the usual deposit of ashes, burnt bone, and charcoal; over this were placed Roman tiles leaning against each other at the top, so as to form an angle and protect the dust beneath. Here also was deposited a denarius of Geta. Another denarius of the above prince was found at some distance; they are both in fine preservation and of exquisite workmanship, and represent the ages apparently of nine and of twelve years.

"Some copper moulds for pastry were also found here, very highly ornamented. Although almost every deposit contained abundant evidence of cremation, yet no discovery has been made of a regular Ustrinum. On one occasion the workman employed to dig, &c. found at the depth of eighteen inches a ring adhering to his mattock, which escaped the slightest injury. It is a signet-ring of the age of Henry the Second, and bears a cypher and an ear of corn in intaglio. Immediately beneath this a beautiful Roman urn was found, adorned with elegant scroll-work in high relief; and descending fourteen feet deeper a mammoth's tooth lying on the sandstone rock. These three last articles were deposited beneath each other in a perpendicular line, and no doubt further fossil remains of the mammoth lay contiguous, of which several indications presented themselves, the tooth weighs seven pounds and three quarters. A variety of articles have been found occasionally deposited at the bottom of the urns, such as rusty nails, whisps of hay or sedge-grass, bits of iron, pieces of lead. &c.; in others a quantity of the common snail-shell, sea-shells, &c. A hit of lead found in one has the precise shape of a pot-hook. A hall of pitch was found at the bottom of a very large amphora, a vessel capable of containing more than four gallons. Balls of pitch were thus frequently put by the Romans into their wine to give it a flavour, and the insides of amphoras were often pitched throughout for that express purpose.

"In one urn was found several balls of clay, which appear to have been kneaded by the hand, and are somewhat elongated."

Dr. Bromet read a note from Mr. H. J. Stevens, of Derby, offering to send drawings of some singular fragments of apparently early Norman work in the church-yard of St. Alkmund.

Dr. Bromet stated that, through the civility of Mr. Stevens's clerk of the works he did examine the fragments alluded to. They are of that coarse reddish gritstone which, it would seem, was employed even for sculptural purposes in Derbyshire and Yorkshire previously to the use of lime-stone. Many have been door and window-jambs, and are embellished with the various interlacings and chimerical animals sometimes found on the more ancient church-yard crosses. Two of them have on one side a series of semicircularly-arched panels, divided by short flat columns, with large flat capitals, such as we often see on ancient fonts, and as these were found in the south-east corner of the chancel, they are possibly parts of the tomb or shrine of St. Alkmund, who was killed A.D. 819.

Dr. Bromet suggested, in furtherance of the objects of this Association, that the secretary be requested to communicate with the minister and churchwardens of St. Alkmund's, and the secretary of the Derby Mechanics' Institution, recommending, in the name of the Society, that all the more ancient sculptured fragments found on pulling down the late church of St. Alkmund, be deposited either in the said Institution's museum, the town hall, or such other place easily accessible to the inhabitants of Derby as to the minister and churchwardens may seem fit.

The following letter from Mr. Charles Spence, of Devonport, was read. It was accompanied by rubbings of incised slabs, &c.:—"I transmit a few observations respecting the church of Beer Ferrers, in this county, which I recently visited. Every admirer of genius will recollect that this edifice possesses a melancholy notoriety as having been the place where Charles Stothard, the author of the 'Monumental Effigies,' was killed. In the church-yard, and against the eastern wall of the church, stands an upright stone which at once relates the manner of his death, and commemorates a man whose fame will never die while archæology has a lover, or science its votaries. The church itself is beautifully situated on the banks of the Tavy, and not far from the confluence of that river with the Tamar; it is built in the form of an exact cross, the length of the two transepts, with the intervening breadth of the nave, being exactly the same as the length of nave and chancel, viz. 90 feet. On the north side of the upper portion of the cross is the vestry room, once the chantry chapel, which according to Lysons was collegiate, and founded for six priests in the year 1328, by William de Ferrers, and endowed with the advowson of the church at Beer Ferrers. This chantry chapel is separated from the rest of the church only by the beautiful canopied monument which probably covers the remains of its founder and his lady: in form it resembles the monument of Aneline, countess of Lancaster, in Westminster Abbey, and like it, is dishonoured by having its interior blocked up so that part of the monument is in the chapel, and part forms the wall of the vestry.

"Altar.—The floor of the Altar (immediately under the communion-table) consists of a slab of marble, eight feet long by four feet wide, which is most beautifully carved with rose-wheel circles and hexagonal elongated departments, sustaining what would seem to have been an altar-stone, about six inches in height, the sides of which are deeply grooved or fluted, in one hollow, with roses interlaced with leaves carved thereon in bold and beautiful relief. The Altar is ascended from the nave by three steps; the edge stones of the upper compartment or step have been beautifully cut in bas-relief with shields, arabesques, &c.

"Chancel.—The chancel and its chapels were separated from the nave and side aisles by a cancellum or screen, the basement of which is still left; it is of Decorated character, and has been richly painted; each of its compartments formerly contained a painting of some saint, and in one the figure of a female may yet be deciphered, but it is in so mutilated a condition that it would be difficult to guess whom it was intended to represent.

"Nave.—The nave is filled with the original open sittings of Perpendicular character, quite entire, and beautifully and elaborately carved. At the north-east corner of these pews is a shield cut in wood, and on the south-east corner is another, whereon are blazoned horse-shoes (arms of Ferrers), and rudders of ships or vessels.

"Windows.—Those of the north transept are very beautiful specimens of Decorated work, as is also the great window of the south transept. Those of the south side of the church are Perpendicular. On the north side the windows are debased and bad. The eastern window, which Hickman states to have been 'a fine one,' has been destroyed since his survey, and a choice specimen of the true Churchwardenic style inserted in its place.

"Painted Glass.—In the south transept is a shield of arms blazoned quarterly, but at too great a height for me to decipher them. Such also was the case in a debased window in the north side of the nave, where appears to be a figure resembling a knight, and a shield argent, charged with a cross gules, but turned upside down. The glass representing Sir William Ferrers and his lady, in tracing which C. Stothard fell and was killed, and which was in the east window, is probably in a deal case (marked glass) which is kept in the north transept. An engraving of it may be seen in Lysons' 'Magna Britannia.'

"Font extremely rude. It is described by Rickman as being of rather singular character. To me it appeared only as a rude imitation by unskilful hands; it consists, to use the words of Lysons, 'of a truncated polygonal shape, resting upon four foliated ornaments, encircled by a band of rather rude execution.'

"Parvise is yet left, but much mutilated. The door and steps leading to it are nearly choked up with rubbish, &c.

"Tombs.—Beside that in the chancel previously alluded to, there is a very beautiful effigy in an arched recess, in the wall of the north transept, representing a knight cross-legged, in the act of rising from his recumbent position and drawing his sword. He is armed completely in mail, over which is a surcoat. The sword is suspended from a broad belt, and his heater-shaped shield is pendent from his neck by a guige or strap—his mailed head rests upon his helmet. The effigy has been broken off at the knees, and the body of the animal on which his feet rested is gone, but the four paws and tail yet remain. The whole monument bears great resemblance to that of Sir Robert de Vere, in Sudborough church, Northamptonshire.

"North Transept.—An Altar has evidently been erected here. The elevated altar-step yet remains, and just before it lies an

"Incised Slab.—It represents a cross, and at the intersection a heart. Irradiated above is an inscription, 'Hic jacet Rogerus Champernowne Armiger cujus anime propicietur Deus Amen.' The Champernownes became possessed of the manor of Beer Ferrers before the close of the fourteenth century. I have seen other, and hope to send for the inspection of the Society specimens of these engraved slabs, which, though somewhat rare in the eastern parts of England, do not appear to be uncommon in this western portion of our country; indeed the old Norman practice of inscribing round the edge of the flat gravestone is still practised here, and almost every church presents instances of it. There is another stone near the foregoing, apparently very ancient; the letters are cut in very deep relief, the words, 'Orate pro Will'mo Champernoun.' Royal arms very coarsely executed on four pennoucels; around are painted a rose, harp, portcullis, and fleur-de-lis.

"Roof entirely modernized, and chancel-arch spoiled.

"In conclusion, I may state that the exterior of the church has a pretty appearance; its nave, side aisles, and the little chapels in the upper angles of the cross, together with its low tower surmounted by a kind of corbel-table, resembling machicolations, look well from every point of observation.

" Such is the church of Beer Ferrers, which Lysons states to have belonged in the reign of King Henry the Second to Henry de Ferrariis or Ferrors, ancestor of the numerous branches of the ancient family of Ferrors in Devonshire and Cornwall."

November 27.

Mr. M. W. Boyle presented through the Rev. J. B. Deane a portfolio of prints and drawings, illustrative chiefly of places in London. It comprises, 1. Illustrations of Crosby Hall. 2. Occupiers of Crosby Hall. 3. Illustrations of St. Helen's Church and Priory. 4. Illustrations of Gresham College. 5. Illustrations of Leathersellers' Hall. 6. Miscellaneous Illustrations.