Archaeological Journal/Volume 1/Remarks on some of the Churches of Anglesey

REMARKS ON SOME OF THE CHURCHES OF ANGLESEY.

COMMOT OF TYNDAETHWY.

The churches of this commot, or hundred, sixteen in number, are mostly of great simplicity of form, and include probably some of the earliest Christian edifices built within the island. The county town of Beaumarais stands within this commot, and its parochial church (which is in reality only a chapel dependant upon Llandegvan) is the largest ecclesiastical building in the district; but it is of a period rather later than that to which attention will be drawn in this paper: and, though an edifice of much architectural interest, must remain for more ample notice on a future occasion. At present all that will be attempted is to give a brief account of a few of the more notable churches of the commot, which may serve as types (and they are well suited to this purpose) for the rest of the island. In general, the villages in the commot of Tyndaethwy are small in size, and scattered in arrangement:—the parishes are not small, but the houses lie far apart from each other, and the district, though well cultivated, has on the whole a wild and bleak appearance. It forms the most easterly portion of the island, and is easily accessible to visitors of all kinds: it contains the frowning feudal castle of Beaumarais, and the beautifully secluded retreat of Penmôn Priory; it is washed by the blue strait of the Menai on the one side, and the stormy inlet of Traeth Coch (Red Wharf Bay) on the other:—so that for many reasons there can be little hesitation in recommending its mediæval remains to the notice of modern antiquarians.

It is the opinion of the learned and acute Henry Rowlands, author of the Mona Antiqua Restaurata, that the earliest ecclesiastical edifices erected in Anglesey (and indeed in Britain) were cells or hermitages, built by the first professors of Christianity who settled within its limits:—that to such cells small chapels, or places of prayer, were attached; and that the people, resorting thither for spiritual instruction during the lifetime of the holy founders, continued to regard them as sacred spots after their decease, and, either immediately or ultimately, converted them into churches under the name or invocation of the holy men, whether canonized by proper authority or consecrated by popular opinion. There is much probability in this hypothesis, when the local peculiarities of Anglesey are taken into consideration:—and it is strengthened, not only by tradition, but also by several circumstances connected with buildings of this class, in other parts of Wales as well as in the island. It is not to be expected that any of these original cells are now to be found standing, though the contrary cannot perhaps be affirmed; but there is such a similarity in the construction of many churches here, and their history generally tallies so well with the suggestion of the author named above, that it may be received as a good starting-point of Cambrian antiquarian doctrine.

One of the local circumstances corroborative of this view of the case, is that the earliest churches still extant are of that small simple form which might have been expected had they been built for the use of a single holy man and a few followers.

The original form of the Anglesey churches seems to have been that of a small oblong edifice from thirty feet by ten feet to fifty feet by twenty feet internally. These would hold about fifty or a hundred persons, and perhaps in early times the rural congregations of these districts rarely surpassed this number. The addition of transepts and chancels seems to have been made at much later periods, generally in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries: but in the conventual establishment of Penmôn, which can hardly be classed with the ordinary parochial churches of the island, the original form of the building was no doubt that which it still retains, cruciform. It is very difficult for a casual observer to recognise the original nucleus of these early churches, but it may be generally discovered in the nave, where the walls are commonly of rude though solid construction, the level of the building sunk beneath that of the external earth, and the windows evidently inserted at some recent period, (often in very late times,) so that originally no light could have been admitted except by the door, or else perhaps by a small eastern window. Without asserting that many of these early buildings remain in the present churches, it may be considered probable that even when a new edifice was erected on the site of an older one, the first plan was adhered to, and that the only change made was that of stone for wood and rubble. The church of Llansadwrn (the church of St. Sadwrn or St. Saturninus) may be referred to as a good instance of the absence of all windows in the original nave:—there are some in the southern side, of the fifteenth century, and a small modern loophole at the western end; but without these the building could originally have had no light. The naves of Llangoed and Llandegvan are similar instances: so is that of Llanvihangel Tyn Sylwy: and even in the conventual church of Penmôn the only fenestral openings in the nave are small circular-headed loopholes contemporary with the building, twenty-four inches by nine externally, but expanding within to a considerable size. These early churches seem never to have been paved or floored, very few of them are so at the present day: the earth, like the soil in the peasants' cottages, is beaten hard, more or less even, and being generally dry serves the purpose of the hardy congregations. The roofs must always have been of wood: no trace of vaulting is to be found anywhere within the commot: and it is by no means improbable that some of the original timber used for these purposes may be in existence at the present day, though the fact can hardly be verified. The universal covering of these roofs is the schistose stone, which composes the largest geological formation in the island. The only approaches to stone-vaulting are to be found at Penmôn and Ynys Seiriol. Here the towers of the two churches are covered with low conical quadrilateral spires, or rather pointed roofs, in the formation of which no wood is employed, but the stones keep lapping over each other from the lowest course laid on the side walls until at length they meet in the apex. A much later example of this rude vaulting, if it can be so called, is in the monastic pigeon-house at Penmôn, a curious square building of the fifteenth century, almost unique in its kind:—the towers above mentioned are about sixteen feet square at Penmôn, and eighteen feet by twelve feet at Ynys Seiriol, but in the pigeon-house the area is twenty-one feet square, and the quadrilateral vaulting approaches to the domical form (like the roofs used by Delorme in the Tuileries, and other French châteaux), and it is entirely covered by stones laid in this manner, without any wood in the whole building, and with a light louvre or lantern in the midst.

Towers were evidently too costly for the construction of the primitive churches of Anglesey, and whenever bells came to be used, the erection of a simple gable at the western end of the building served the purpose. All these gables however have pointed arches, either of the end of the thirteenth or the fourteenth centuries; and hence it may be suspected that the use of bells was an ecclesiastical luxury of comparatively late introduction into Anglesey. However this may be, their form is very simple: covered generally with a straight coping, but at Llansadwrn with one of a peculiarly elegant curve. At Penmynydd (which is the largest church in the commot next to St. Mary's at Beaumarais) the gable is pierced for two bells; but this is a rare instance of parochial wealth.

The churchyards retain perhaps the same size and form which they originally possessed: a fact which, in the absence of documentary evidence, may be inferred from the peculiarly religious spirit of the inhabitants, who still retain in undiminished vigour the national respect for sacred things: and which has never allowed them, except in the calamitous period of the dissolution of the monasteries, to encroach on consecrated ground. The absence of monumental slabs would lead to the inference that no interments (as a general rule) took place within the churches. There are exceptions to this at Penmynydd, where the tomb and vault of the Tudor family still remain, and where there is also a tomb under an arch in the northern wall of the building, to accommodate which a small erection like a chapel (without any windows) has been added to the original edifice. This tomb is of the fourteenth century (?), but bears no sculpture or inscription of any kind by which its possessor's name can be discovered, though it is very probably that of a Tudor, the seigneurs of the parish from time immemorial.

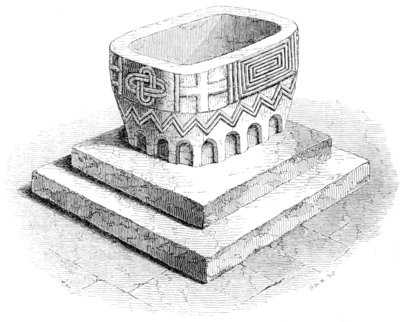

Of early fonts only two remain in this

Water stoup, Penmôn commot: one at Penmôn, probably the earliest: the other at Llaniestin: they are both no doubt contemporary with the buildings in which they are placed. The other fonts, which more or less resemble that of Llanvihangel Tyn Sylwy, appear to be of the fourteenth century. At Penmôn until within a few years a water-stoup, of the same date as the font, was used; and at Llandegvan another water-stoup (of the fourteenth century?) is still employed for the baptismal sacrament: in all cases these fonts are placed at the western ends of their respective edifices, sometimes against the northern, sometimes against the southern walls.

The gables appear to have been always topped with crosses, the pediments of which, commonly quadrangular with trifoliated canopies, still remain: but of the crosses themselves a considerable proportion have perished. Those at Llanvihangel, Llangoed, and Llansadwrn are the most remarkable[1].

The chancels and transepts seem to have been all added posterior to the conquest of Wales by the English, and their architecture indicates in general the style of the fourteenth century. The chancels are mostly of the same design: the transepts, if indeed they may be so called, have been only chapels added by the parochial gentry, as at Llangoed, Llandegvan, &c.

The following is a list of the ecclesiastical edifices in this commot:—

Ynys Seiriol, (St. Seiriol's Isle, Priestholme, or Puffin Island.) The tower of a small conventual church still remains here: and the foundations of part of the church, with perhaps part of the monastic cells, may be traced: it is exactly similar to the tower of Penmôn. This small conventual establishment is noticed both by Dugdale and Tanner, though they do not seem to have been aware of the existence of two distinct establishments, churches, &c., on the mainland at Penmôn, and on the island, the original name of which was Glannauch, or Ynys Lenach, "the Priest's Island." St. Seiriol, according to Rowland's Mon. Antiq., flourished with St. Cybi in the seventh century.

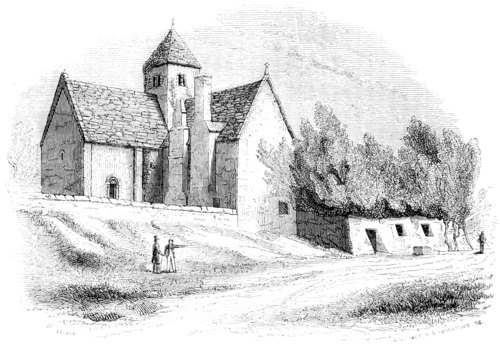

Penmôn, an Augustine priory. Here are to be found the conventual church, the refectory, part of the prior's lodgings(?), and some of the conventual farm buildings.

Compartment of Font. N. side. With the house on Ynys Seiriol, it owes its foundation to Maelgwyn Gwynedd, king of Wales, in the sixth century, and was re-founded by Llewelyn ap Jorwerth, prince of Wales, at the beginning of the thirteenth century. The conventual church consists of a nave and south transept of early date, and a chancel of the fifteenth century; the northern transept has been destroyed,

West Door, Penmon. but the central tower still remains. The south transept was used as a chapel, and a curious series of small circular-headed arches, with zigzagged mouldings and filleted shafts, formed seats round its sides for the monks and their attendants. The buildings are in good preservation, though somewhat in need of repair; but they belong to a gentleman of enlightened taste and public spirit, Sir R. W. Bulkeley. The chancel only is used as a parochial church.

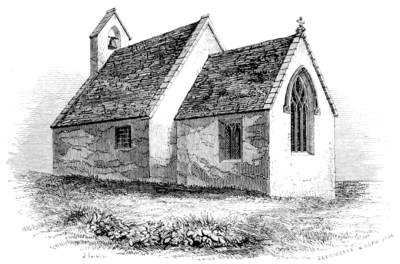

Llan Sadwrn. a small church consisting of a nave, and a chapel on the northern side.

Inscription to St. Sadwrn. The nave is probably of very early date. The chapel and the eastern window may be assigned to the fourteenth century. By the side of a window in the eastern wall of this chapel is an inscription commemorative of St. Sadwrn, which the early form of the letters would lead us to suppose older than the Norman conquest of England. I conjecture the reading to be—

HIC BEATVS SATVRNINVS SEPs (SEPULTUS) JACET' ET SVA SCa (SANCTA) CONJVX' PAX.

DETAILS AND SECTIONS, PENMON PRIORY CHURCH.

Llan Ddona. a small church dedicated to St. Ddona, a grandson of Brochvael Yscythrog, who commanded the Britons in the fatal battle at Bangor Iscoed, at the beginning of the seventh century. It consists of an early nave with a northern porch, and a chapel or aisle on the south side. To this nave is added a cruciform building forming a chancel, and two transepts of the fourteenth century.

Llan Degfan, (or Llandegvan.) A long low church with an early nave, and a chancel of the fourteenth century. Two chapels have since been added, forming north and south transepts. A tower was built at the west end of the church in 1811 by the late Lord Bulkeley. Dedicated to St. Tegvan.

Llangoed. a small church with early nave; chancel and transepts of more recent date; the eastern window is as recent as 1613.

Llanfaes. This is the parish church of the village in which the friary of Llanfaes was subsequently built. The nave is of the thirteenth century, as a doorway in the northern side testifies: the choir is of the end of that century, or the beginning of the fourteenth. The tower was erected by Lord Bulkeley in 1811. Of the religious house just mentioned, which was founded and filled with Franciscan friars in by Llewelyn ap Jorwerth, in memory of his consort the Princess Joan, daughter of King John of England, hardly any thing remains except the church, now converted into a barn and stable. The nave and chancel are still entire, though the interiors are scarcely to be made out. Of the magnificent altar-tombs contained in this church, one is in the church at Beaumarais, another at Penmynydd, a third at Llandegai in Caernarvonshire, and a fourth at Llanbublig, the Roman Segontium, in the same county.

Penmynydd. This church, which constitutes a prebend in the cathedral church of Bangor, consists of a nave with a sepulchral chapel on the northern side, and a chancel. There is a porch on the southern side of the nave. The whole building is of the end of the fourteenth, or beginning of the fifteenth century. In the chancel stands the magnificent alabaster monument of the Tudor family, whose vault is underneath. It is a work of the fourteenth century, of admirable execution, but rather mutilated. Some careful repairs (not restorations) have been ordered of this valuable work of medieval art[2]. At the western end of the nave is a minstrel gallery in wood of the sixteenth century. The church is dedicated to St. Gredivael.

Plan of Lanfihangel Church

Llanfihangel Tyn Sylwy. So called from its being situated beneath the elevated British station of Dinas Sylwy—or Bwrdd Arthur, Arthur's Round Table—is a small church apparently altogether of the fourteenth century, though the nave has probably re-placed one of earlier date. The chancel is decidedly of the fourteenth century, and is of remarkably elegant proportions. In the southern corner of the chancel stands a curious moveable wooden pulpit of the seventeenth century, the elaborate decorations of which have been burnt out by a red hot iron stamp, leaving the surface of the wood charred black to the present day. This church like others of the same name is dedicated to St. Michael the Archangel.

Part of Roof, Llan Tysilio.  Springer of the Roof. |

East Window, Llan Tysilio |

Llan Tysilio. a small and remarkable church, built in a most picturesque situation, on a little islet immediately

Section of window, Llan Tysilio. on the southern side of the Menai Bridge. The nave is probably an early one: the eastern window is of the fourteenth century. The wood-work of the roof is curious, from the trifoliation

The Plan, Llan Tysilio of the side springers where they meet in a point above, and from their edges being chamfered, with square pointed bosses left in the midst of the chamfer, giving a most excellent effect at a very moderate cost of labour and expense. Dedicated to St. Tysilio.

modern repairs: and a small vestry on the northern side of the nave containing one of the alabaster tombs from Llanfaes. This tomb, though mutilated in former days, is now in a place of comparative safety, and is well taken care of. There are numerous mural tablets in the church, one of which, a small brass, commemorates some early members of the Bulkeley family: and another, an incised slab south of the altar, bears the armorial coats of Sir Henry Sidney and other officers of Queen Elizabeth's reign. The richly carved oaken roof of this church is well worthy of note: in the chancel the carved stall-work (brought from Llanfaes?) has been arranged in a judicious manner. The whole edifice is in good repair with the exception of portions of the chancel.

There are some other churches in this commot which have not yet been included in the author's survey, viz.:

Llan Bedr Goch, Llan Ddyfnan, Llanfair yn Mathafarn Eithaf, Llanfair Pwll Gwyngyll, and Pentraeth. The latter is figured in Grose's Antiquities.

H. L. JONES.

- ↑ The early and highly curious cross, or crossed stone, standing in the park at Penmôn, is not here taken into account.

- ↑ It is a curious and unfortunate superstition of the peasantry, that a portion of this and similar monuments, if ground into powder, will form a specific collyrium for weak eyes. The depredations which have hence resulted are most serious. The tomb is going to be re-set, and a stout railing placed round it.