Cassell's Illustrated History of England/Volume 3/Chapter 9

CHAPTER IX.

PROGRESS OF THE NATION.

CONSTITUTION AND LAWS.

The entire break up of the ancient system of the kingdom, which occurred in the reign of Charles I., the destruction of the monarchy, which had lasted from the conquest 582 years, and the establishment of a commonwealth, attended by an equal revolution in the national religion, and numerous other changes of a more permanent and influential character, make it necessary for us to review the circumstances of the nation at a much shorter date than we have previously done. As monarchy after this period was again introduced and continued, it becomes absolutely necessary to treat of the portion of history including this great revolution at its termination, that we may contemplate as a whole its character and effects, not only immediate, but as operating under the revived form of monarchy, and continuing to operate as yet. We shall then have cleared the ground, and can start afresh, under regal institutions, more perspicuously.

In detailing the events of the reigns of James and Charles, and of the commonwealth itself, we have taken the opportunity to state our views of the characters of the chief actors in them, and the motives and causes which led to and effected such stupendous changes, so that our review may be the more brief and general.

The contests betwixt the crown and the aristocracy have occupied a prominent part of this history for the great period of the monarchy. During that long period of more than four hundred years, the people presented a comparatively unimportant feature in the nation. Their wishes were little regarded, their interests were scarcely recognised. Occasionally they rose in their strength, and reminded the higher classes that they were a power, if they were fully aware of it; but their soon sank again with the concession of their demands in quiescence, and an immense toleration of exactions and oppressions. But as the nobility declined, not only monarchy, but the people acquired additional importance. The distribution of the property of the church and of confiscated estates, and the progress of trade and general intelligence, rapidly raised the people into a visible third estate, and the commons in Elizabeth's reign assumed a position of considerable dignity and force, which even that high-spirited queen was compelled to bow to. But it was not merely the national benefits which the reformation brought to the people which developed their importance, it was the dissemination of the Bible, and its reading for themselves, which opened up to the general mass of the population a new idea of the great moral laws. In that august treasury of divine principles they saw the rights of the human race written in luminous and incontrovertible characters, and the whole framework of social polity became reversed in their minds. They perceived that the race was not made for the rulers, but the rulers for the race. That mankind was the great object of the divine intentions, the mere institution of kings and nobles were accidents which had grown out of the ascendency of physical power in barbarous times, and which had been invested with splendour, ceremony, and etiquette, by state-craft, to give them pre-eminence over the ignorant multitudes. This once discovered and reflected upon, men rose in the conscious dignity of their own nature, and very soon in England and Scotland, the third estate, as it was called, became in reality the first estate, for it was now perfectly aware that out of it proceeded the life-blood of the government, the supplies for all its exigencies, and that it had but to raise its voice to be heard throughout every department of the state, every corner of the realm.

The expression of this power did not become so apparent during the reign of the Tudors as the Stuarts; but under that haughty and dictatorial dynasty, the sentiment itself was growing and ripening rapidly, like seeds swelling and generating in the earth, though not yet emerged from it; and the whole was the more fervent and indomitable because it sprung from the same source, and grew with the same growth as the new discoveries in religion. These newly recognised rights were perceived to be the rights proclaimed by the universal Father, through the pages of the same book which brought spiritual life and immortality to light. By this common origin political principles were elevated into sacred ones, and invested with all the solemnity of duty.

James VI. of Scotland had been educated amid the intense fermentation of these discoveries. The very ground, as it were, heaved under his cradle with the convulsive energy of the awaking powers of the gospel amongst the serious people of his kingdom. Knox and his associates had imbibed in Geneva the most stern and most ascetic principles of the reformers. They were persuaded, with their master Calvin, that all human institutions must submit themselves to the church of Christ, and Calvin himself, in his condemnation of Servetus, gave them a practical proof of his persuasion that heresy as well political tyranny must be exterminated in its advocates. Thus not only their own rights, but the intolerance of the rights of others, were established in the minds of the earnest Scotch people; and accordingly their zeal burst forth in a most uncompromising and exacting form. They drove James's mother from the throne in their intolerance of her popery; and when he himself began to rule without the restraint of his guardians, the ministers of the reformed kirk assumed a censorship of his words and conduct, and treated him with a rude and overbearing familiarity, which excited in him an everlasting horror of presbyterianism, the form of worship which the bulk of the Scottish people had adopted.

In 1596 the general assembly sent a deputation of four ministers, including James and Andrew Melvil, to James, at Falkland, to admonish him of the wickedness of the country, the king's own habit of "banning and swearing," the queen's not repairing to the preaching of the word, but indulging in balls and dances, the encouragement of superstition in permitting pilgrimages, singing of carols at Yule, profanation of the sabbath, wanton games, drinking, tribes of idle, dissolute people, as fiddlers, pipers, sorcerers, strong beggars living in harlotry, and not having their children baptised, the neglect of justice, and the appointment of ignorant or wicked men to offices, as well as allowing such sacrilegious persons as abbots, priors, and dumb bishops, voting in parliament in the name of the kirk.

James growing out of patience at their catalogue of crimes and delinquencies, one of the ministers pulled him by the sleeve of his coat, telling him that the country was in danger of wreck through the truth not being told him; and informing him that though he was a king in a certain sense, yet of Christ's kingdom, that is, the kirk, he was neither king, nor head, nor lord, but only a member; and that neither king nor prince should be allowed to meddle in it. These visits to the king were frequent, and the same intended for the queen, but she seemed to avoid most of them. They then attacked her unmercifully from their pulpits, censuring, in the strictest terms, her neglect of their preachings, her going to episcopal clergymen, her not introducing religious exercises and virtuous occupation amongst her maids, nor having occasionally godly ministers to instruct them. One David Black, a minister of St. Andrews, from his pulpit declared that all kings were devil's bairns; that the devil was in the court, and the guardian of it; that the queen would never do them any good; that the nobilty were godless dissemblers and enemies to the church; and the members of the king's council hourglasses (that is, buffoons), cormorants, and men of no religion. When James summoned him for this gross language before the privy council, the kirk took it up, and declared no clergyman was amenable to any power but the kirk itself.

Copied from Authentic Sources.

It is no wonder that with this claim to independence of and indeed superiority to the state, and a disposition to make so free a use of its censures, James should feel no particular fondness for such a church, and should labour to restore episcopacy, which was always more respectful to royalty. In fact, though James in 1590 made the speech, so constantly recalled to his memory when he was doing his utmost to give the supremacy to episcopalism both in Scotland and England, declaring in the general assembly that "it was the purest kirk in the world," presbyterianism, though by far the most generally accepted religion in Scotland, was not acknowledged as the established church there till 1592; and in December, 1596, episcopacy was fully restored again both in church and state, so that it was only four years the legal establishment previous to James's accession to the English throne.

When James arrived in England, he found a very different state of things. Though dissent from the forms and ceremonies of the church was very extensive, it had been restrained with a high hand, and there was no other visible church which had risen face to face with the state church, so as directly to menace it or the monarch. Both in Scotland and England the doctrines of all believers were mainly the same; the difference was as to outward forms. The puritans, as they were called, still occupied established pulpits, for conventicles, as they were called—that is, dissenting chapels—were strictly restrained. What the non-conformists sought was freedom in the church for their more simple tastes in ceremonials. The celebrated Millenary Petition, presented to James on his way into England, signed by eight hundred ministers, demanded but a few and apparently unimportant concessions to preserve the unity of the church. They objected to the cross in baptism, the interrogatories to infants, baptism by women, the ring in marriage, confirmation, and a few other minor particulars; and these granted in the churches to those who had a conscience on such points, would have preserved the integrity of the church. The demands of the ministers at the Hampton Court conference were substantially the same.

James, therefore, surrounded by a different hierarchy, and seeing dissent assume so much humbler a form, suddenly felt himself inspired with a greater love for episcopacy, and an intenser horror of dissent, which, in its Scottish shape, had so wounded his kingly dignity. He therefore carried matters with a high hand both in church and state, and the insolence and intolerance of his archbishop Bancroft did more to drive the dissidents into open sectaries than all that had been done before. Charles, educated by his father in all his Jesuitry of kingcraft, and taught at once to believe in the divine right of kings, and to attach no sacredness to his word in seeking to acquire absolute power, being of a bolder and more sanguine temperament, soon marched headlong on destruction. We have already carefully detailed the steps by which Laud and Wentworth, and his own imprudent spirit, led him to the block. He had, following in the steps of James, roused all the zeal both of the politicians and the religionists against him, and in the war to the death which was waged by his subjects with him, these two principles went from first to last hand in hand. The oppression of conscience both in Scotland and England had created a deep sympathy betwixt the people of both countries, and vast numbers in England had adopted the same presbyterian idea of church government as prevailed almost universally in Scotland. When, therefore, the questions of ship-money, and other unconstitutional impositions, the king's forcible invasion of the privileges of the commons, and his evident intention to make himself independent of all restraints from his people, had brought his chief ministers to the block, and himself in arms against his parliament, the demand became not only for the restoration of the popular guarantees, but the destruction of episcopacy, and the substitution of presbyterianism. It now depended on the prevalence of different parties what form the future government, as well as the church, should assume.

Exiled Nonconformists Landing in America.

If those who objected to legal exactions, but dreamt neither of overturning the government nor the church, had prevailed, amongst whom we may include lord Falkland, Clarendon, Colepepper, lord Capel, lord Digby, and even Pym and Hampden, the crown would have received the necessary checks, and the episcopalian church would have continued. But some of these chiefs, as Falkland, Hampden, and Pym, died early in the struggle, and the rest joined with the king in endeavouring to resist further encroachments to the utmost and to the last. Had the presbyterian party prevailed, monarchy would have continued, but England might now have been existing without its episcopal hierarchy. But as it happened, men of more republican principles, and of still more liberal ideas of church government, proved the ablest heads, and gave for a time the decisive character to the nation. These were the independents, anabaptists, and fifth-monarchy men, who constituted the leaders of the army, and who leavened the whole of the forces with their principles.

These circumstances led to the destruction of the monarchy, and with it of the episcopal church as the state church. Among these republican chiefs, however, Cromwell, the independent, developed infinitely the most capacity for command and for government; and from the difficulties of his situation, surrounded by the conflicting parties of royalist presbyterians, who would suppress his free notions of religious government, and a mass of ultra republicans and religious zealots who went far beyond him, he was compelled to seize the entire reins of rule, and the commonwealth became a dictatorship. Had these violently opposing elements not existed to the extent which they did, England might then have "become and remained a pure republic, governed by its president and its parliament, or the descendants of Cromwell might have been to-day seated on the throne of England. But the same predominating impulses which deprived Cromwell of the power of riding by a free parliament, and compelled him to remain a dictator, equally foreshowed the inevitable termination of the prevalence of his principles of government with his life. The chaos of parties, political and religious, which raged around him, was certain, as it immediately did, to destroy itself, and leave open the way for monarchy and episcopacy.

We have, therefore, here only to consider what was the nature of Cromwell's dictatorship, and what its effects present and parliament. And in the first place we must admit that after all necessary concession to the charges against Cromwell of personal ambition, and of his having terminated all his professed struggles for liberty and constitutional right by seizing the helm of government himself, and ruling according to his own will, there is no other instance of military conquerors who have used their power so entirely for the public benefit, and so little to the restraint of individual freedom. His rule, though centring in himself, was not for himself, but for the people; it was not one of absolutism or oppression, but of cordial and earnest endeavour for the general welfare, and embraced the greatest freedom that had ever yet existed in England.

As the career of a mere country gentleman, scarcely raised above the condition of a gentleman farmer, and till upwards of thirty years of age distinguished for nothing but his retiring life and religious habits, and till forty-three ignorant of military command—'twas marvellous. Julius Caesar, to whom he has been compared, was educated as a great patrician, was practised in all the arts, and possessed of all the influence by which men distinguish themselves in the chief arena of a nation. He was a splendid orator, and an accomplished and experienced general; and when he seized on the dictatorship of his country, it was to repress liberty, and hold his station for his own glory by a rigorous and military repression. But though Cromwell had everything of the military science to learn when called upon to command, he soon showed that he had the genius and the conquering will. Every enemy, king, baron, and cavalier, whose profession was naturally of arms, fell or fled before him; and Marston Moor, Naseby, Dunbar, and Worcester, spread his fame as an invincible hero through the whole world. When he arrived at the chief power, he extended and confirmed this fame. He beat down the haughty insolence of the Dutch at sea, impressed France with the terror of his arms, and inflicted a terrible chastisement on Spain, which had so often sent her armadas against protestant England, and stirred up all the catholic animus on the continent against her. He made pope and pagan tremble, taught Savoy to respect the rights of conscience, and Algiers the rights of merchants; he did that in Scotland which no English monarch could ever accomplish before him, not even om- great martial Edwards and Henrys—he thoroughly subdued the hardy valour of the Scots, and kept that country in peaceful subjection till his death.

When he came to administer the civil government he would fain have given parliament the most perfect freedom, if it would only have consented to leave his own position unassailed. Even as it was, he permitted the most uninfringed personal liberty; and as to religion, there never had been so much freedom of conscience enjoyed since the Conquest. Though himself an independent, he permitted presbyterians or other professors to hold livings in the church, so that they preached sound doctrine, and maintained a religious life. He took immense pains by his commissioners to purge the ministry of corrupt, unsound, and inefficient preachers, and to introduce better men, without regard to the particular sect to which they belonged. If we compare the commonwealth, in respect to either civil or religious liberty, with the monarchy under the Tudors and the Stuarts, and what it became again after the restoration, the change is wonderful. Instead of burnings, brandings, cutting off of ears, slitting of noses, the torturings, fleecings, and insolent oppressions and cruelties of the Star-chamber and High Commission Court, the change might well be termed like one from hell to heaven. In all Cromwell's addresses to parliament, he urged on them the necessity of bringing the truth and purity of Christianity into the daily practice of fife and government, and his own court was in perfect keeping with his inculcations. There everything was orderly, decorous, and dignified. No scandalous libertines could find countenance there. He exhibited the same honest and patriotic spirit in sweeping away the corruptions of the law and the corruptions of the bench. His reform of the hideous court of chancery, and his appointment of upright judges, astonished the whole country; and such was the general vigour of both his foreign and domestic administration of affairs, that his very enemies, as we have seen, were compelled to express their admiration, and to name the days of his government "halcyon days," and to confess that the name of England never stood so high in the world.

Such were the effects of Cromwell's ride for the time; and the only remaining question is, what have been its permanent effects on the welfare of this country, and on history at large? It would be difficult to estimate the extent of the beneficial influence of the English commonwealth on general liberty and civilisation. The solemn and striking example of a nation calling its monarch to account for his attempts to destroy the liberties of his country, condemning and executing him for his treason to the state, was a lesson to all monarchs and all subjects, that will never be forgotten whilst the world stands, and has been already imitated in France. The very enormity of the military force by which Europe at present is held in slavery, is but a confession of the consciousness that the principles of the British wealth are now become the principles of all peoples; and we may safely assert that those principles, though defeated for a time, are only delayed in their inevitable action.

The commonwealth also laid down the great maxim that all power proceeds from the people, even that of deposing and electing kings. It thus destroyed for ever the pernicious doctrine of the divine right of kings—the cornerstone of all oppressions and all official insolence; and though this great principle seemed again destroyed by the restoration, it survived, and was established permanently in the British constitution at the revolution of 1688, the bill of rights expressly recognising it; and William of Orange, though the grandson of Charles I., and married to the daughter of James II., was not received by hereditary right, but avowedly by the election of the people. These are great hereditary legacies of the commonwealth to as and to the world. France has adopted the same principle and acted on it repeatedly. The United States have exercised the same right against us, and have become a republic; and there is no principle now more extensively diffused amongst all thinking people as a perfectly common sense truism, and though outwardly ignored by kings, not forgotten by their subjects.

A Friend's Meeting. From an Engraving of the 17th Century.

During the commonwealth many improvements were introduced into Ireland under Ireton's administration, particularly that of changing provincial courts into county courts, greatly to the convenience and relief of the people. The system of lease and release came into use in this kingdom; the greater feudal services were abolished; and, to the especial honour of the commonwealth, torture was disused. This practice, which was totally opposed to the law of England, and had been used in every reign of the government, often with cruelty equal to that of the Spanish inquisition, was abandoned by the commonwealth, and never again was restored. How far the great men of the commonwealth were in advance of their age in this respect, Mr. Jardiue, in his treatise on the subject, has shown by reminding us that torture was not abolished in Scotland till 1708; in France till 1789; in Russia till 1801; in Bavaria and Würtemburg till 1806; in Hanover till 1812; and in Baden till 1832; and not even then in reality in the prisons of those German states, for cudgelling was still employed there, in menacing prisoners to compel confession, as may be seen in the trials recorded in the Neue Pitavel, and especially in the case of Wendt, the cabinet-maker at Rostock.

Whatever constitutional principles, therefore, were violated in the struggle which resulted in the commonwealth, whatever miseries were inflicted during its violent warfare, and however brief was the period of its existence, the advantages to us and to all mankind were incalculable in their amount, and eternal in their nature. By it the royal, mysterious, indefatigable, and protean power called prerogative, a law above all law, was struck down, and, if not destroyed, made subject to parliament; and the powers and jurisdiction of parliament, the great legislative and judicial authority, placed on a clear and immovable basis. Since then kings have ceased to be a terror, no man is in peril of being dragged from his home to be tortured and robbed in Star-chambers and High Commission Courts, at the pleasure of the prince and his parasites; and if we are ill-governed we have only ourselves to thank for it. Such is the debt of everlasting gratitude that we owe to the great men of the commonwealth, and to none more than to Oliver Cromwell, the dictator.

RELIGION.

During the reign of James, and during that of Charles, so long as he might be said to reign, the great endeavour was, both in England and Scotland, to maintain the episcopal hierarchy, and to put down popery and puritanism. In this James succeeded to a considerable extent on the surface. He restored and strengthened episcopacy in Scotland, actually engrafted it on a presbyterian church, and it lasted his time. In England he carried his episcopalianism with a high hand. Dissent there yet, for the most part, was not visible, or lay half-concealed under the form of non-conformity; no great actual separation from the established church having taken place till his archbishop Bancroft forced this outward avowal and practical secession by his new book of canons, in 1604, the very year after James came to the English throne. These canons enjoined the ceremonies objected to by the nonconformists—bowing at the name of Jesus, kneeling at the sacrament, wearing the surplices, &c. These being enforced with rigour by Bancroft, in about six years no fewer than three hundred ministers were deprived or silenced. Here, then, commenced actual and public dissent, for the nonconformists being no longer able to exercise their spiritual functions in the established church, they and their congregations separated, and opened their own chapels, or conventicles, as they were called; and James and Charles continued to fine and persecute the papists on the one hand, and the dissenters on the other, till the resistance to Charles's liturgy in Scotland in 1636 and till the rebellion in England relieved both countries from the tyranny of royalty and episcopacy. In Scotland, indeed, the imposition of the canons of the episcopal church had not led to actual separation, but to these private meetings for worship after the people's own heart, in private houses and on moors and mountains, which, after the renewed persecutions of the restoration, became so prevalent amongst the covenanters. These practices commenced after the introduction of a liturgy by James in 1616, and were still more extended after the introduction of his "Five Articles" in 1621, and all the cruelties of fines, banishments, and imprisonments were put in force against them.

In England the church, encouraged by the crown, acted with a high and rigorous hand so long as royalty was in the ascendant. We have described the deeds of the tyrannic prelates of the Anglican church in these reigns, their Star-chamber and High Commission Court atrocities, their imprisonments, their torturings and brandings for conscience' sake. Their terrible treatment of Leighton, Prynne, Bastwick, Benton, and numbers of others. There was an ascent of prelatical evil through Parker, Whitgift, and Bancroft, to Laud, who completed the climax. No period of the Spanish inquisition presents more horrors than were perpetrated by those high priests in the name of religion. The catholics accuse Charles of having put to death ten of their clergymen in the early part of his reign, for the exercise of their religion.

But what was not less extraordinary was the fact, that whilst these cruelties were committed, because men would not conform to mere ceremonies, the most extensive and deep-seated heresy in doctrine crept into the church, and some of these very persecuting prelates were the heresiarchs. Though James took so violent and remorseless a part in persecuting the Arminian Vorstius, on his appointment to the professorship of divinity at Leyden, in 1611, and sent four English and one Scotch divine to the synod of Dort, in 1618, to assist in establishing the Five Points of Calvinistic faith—namely, absolute predestination; the limitation of the benefits of the death of Christ to the elect only; the necessity of justifying grace; the bondage of the human will and the perseverance of the saints—and never left the pursuit of Vorstius till he had ruined him; yet the doctrine of Arminius, that of free will, crept into his own church, and prevailed to a great extent, unnoticed by him, amongst the bishops and dignitaries. In fact, so long as the outward form and ceremony were maintained, little quest was made after doctrine. Laud, whilst he was persecuting the really orthodox in opinion with the frenzy of an inquisitor, was himself a thorough-going and undisguised Arminian, at the same time that he was a very catholic in pomp and parade of ceremony. In fact, in him and his adherents blazed forth that pseudo-catholicism which has revived again in our day under the name of Puseyism.

"The new bishops," says Neal, the puritan historian, "admitted the church of Rome to be a true church, and the pope the first bishop of Christendom. They declared for the lawfulness of images in churches, for the real presence, and that the doctrine of transubstantiation was a school nicety. They pleaded for confession to a priest, for sacerdotal absolution, and the proper merit of good works. They claimed an uninterrupted succession of episcopal character from the apostles through the church of Rome, which obliged them to maintain the validity of her ordinations when they denied the validity of those of foreign protestants. Further, they began to imitate the church of Rome in her gaudy ceremonies, in the rich furniture of their chapels, and the pomp of their worship. They complimented the Roman catholic priests with their dignitary titles, and spent all their zeal in studying how to compromise matters with Rome, whilst they turned their backs upon the old protestant doctrines of the reformation, and were remarkably negligent in preaching, or instructing the people in Christian knowledge."

When the church was struck down with the monarchy, the religious parties in the ascendant were the presbyterians and independents, besides a large mass of anabaptists and fifth-monarchy men; all were of the Calvinistic creed, and might have coalesced well enough on doctrinal points, but differed greatly as to modes of church government. Had the presbyterians succeeded in securing the supreme power, the nation would only have exchanged one religious despotism for another, for they were as intolerant of all other creeds and parties as the episcopalians themselves. Cromwell and his independents saved this nation from the gloomy asceticism, which in Scotland had established a right on the part of the ministers to exercise the most unheard of interference in the private habits of individuals and families, a watchfulness, a surveillance over all the motives, opinions, tastes, and wishes of every soul in their flocks, which not even the practice of confession amongst the catholics could exceed in pressure is a priestly yoke. The anabaptists and fifth-monarchy men were ultra-republicans. The former were the crude material of the modern English baptists, who gradually moulded their opinions and practices into very much the same character as those of the independents, except as it regarded their distinctive tenet of baptism itself. The fifth-monarchy men held that as there had been four great monarchies, the Assyrian, the Persian under Cyras, the Greek and the Roman, the fifth and last was to be that of Christ, who had promised to come and reign on earth. They were, therefore, for establishing this fifth-monarchy at once; their government was to be a theocracy, the people being only under their God. These zealots, believing in a grand truth, had only antedated the millennium by an indefinite time, and long before the world was ripe for it. Some of Cromwell's generals, Harrison especially, were enthusiastic fifth-monarchy men, and had to be held, and with difficulty, in check.

But the strong hand and sense of Cromwell, so long as he lived, had enabled him to maintain a free church, in which all men of red Christian faith and feeling were permitted to officiate, except insubordinate episcopalians and catholics. Moderate episcopalians, who could conscientiously hold livings, were not expelled, so that they were of religious lives, and did not interfere with the existing government even, says Cromwell, a few anabaptists were in it. To papists the liberality of Cromwell never reached; he considered them, with the rest of his age, as belonging to the mother of superstition, and objectionable as the avowed adherents of a foreign and hostile power. Though the protector was on the whole averse to persecution, yet the fines on recusants were dilligently levied, and the presbyterians, perhaps for the most part without his knowledge, persecuted other religionists under the commonwealth—a fact amply demonstrated by the history of the Society of Friends, for during the commonwealth arose that singular people.

The doctrines and conduct of the Friends, or, as they were Boon denominated, the Quakers, marked another epoch of that age in the advance towards the true understanding of Christianity, and the acquirement of its freedom. We have seen, that notwithstanding all that the nonconformists had suffered, notwithstanding all the great minds and noble hearts which had appeared among them, they had not yet come to perceive the full and true liberty of Christ. They objected to certain ceremonies and habits, and certain religions opinions, but they did not object at all to the establishment of a state religion,—many of them not even to the episcopal hierarchy, but were a part of it. The independents had made the nearest approach to the apprehension of perfect freedom; they had adopted and acted upon the opinion, that every congregation is independent of all others, and that no minister of the gospel possesses any jurisdiction over another; but they still admitted the right of a state establishment, and under Cromwell accepted office in one. The Friends not only proclaimed the doctrine that all state establishments of Christianity are unscriptural, but that they, violate the political rights of the subject; they therefore denounced all usurpation of human lordship over conscience; all hireling teachers of a state creed, tithes, church rates, and every ecclesiastical demand whatever. To George Fox we owe this bold and manly system, this sudden leap from the chains of long spiritual slavery, into the full freedom of the gospel law—a man to whom there has never yet been done full justice beyond the pale of his own society, and whom we have recently seen attacked by lord Macaulay with an animus extraordinary in a descendant of this society. Macaulay has represented Fox as half an idiot, but it would be far better for the world if it had more such idiots. It would be enough to set aside this splenetic opinion of a writer who has taken every opportunity to vilify the great men of Quakerism, to place against his opinion that of some great thinkers of our own country and time. Coleridge, from whom so many modern celebrities have drawn what is original in their philosophy, Emerson and Carlyle included, says, "There exist folios on the human understanding and the nature of man, which would have a far juster claim to their high rank and celebrity, if, in the whole huge volume, there could be found as much fulness of heart and intellect as burst forth in many a simple page of George Fox." Carlyle says, "This man, the first of the Quakers, and by trade a shoemaker, was one of those to whom, under ruder form, the divine idea of the universe is pleased to manifest itself; and across all the hills of ignorance and earthly degradation, shine through, in unspeakable awfulness, unspeakable beauty on their souls; who, therefore, are rightly accounted projects, God-possessed. Mountains of incumbrance, higher than Ætna, had been heaped over that spirit; but it was a spirit, and would not be buried there. That Leicester shoeshop, had men known it, was a higher place than Vatican or Loretto shrine. Stitch away, thou noble Fox! every prick of that little instrument is pricking into the heart of slavery and world-worship and the mammon god. Thy elbows jerk in strong swimmer strokes, bearing thee into lands of true liberty. Were the work done, there would be in broad Europe one free man, and thou art he."

The opinions of great men, English and American, might be numerously added, but they are the fruits by which we must recognise the tree; and from no religious reformer has the modern world received, and is receiving, more substantial benefit in weaning it from forms and task-masters to spiritual freedom. The awl of Fox still goes on pricking into the heart of slavery, world-worship, and the mammon god. I do not intend to exempt him from the charge of a certain degree of fanaticism—both he and his adherents were not altogether free from it; but the theory of his religious belief comprehended the ideal of all religious freedom. And this arose in part from that want of education which the outward-tending mind of Macaulay has seen only as a defect. Free from every educational dogma, he became struck with the importance of religion, and taking the Bible with him into the fields, he there carefully studied it, and soon discovered the true native of this beneficent

Declaration of Independency at the Savoy, September 29, 1658

Arrest of Nonconformists.

Rev. John Owen, D.D.

Whatever his sagacious mind once embraced as truth, he had the integrity and boldness to proclaim everywhere. He advanced into the presence of princes, and declared it there with the same ease and freedom as amongst his own peers. It may well be imagined, that when numbers began to flock around him, and from every class of society, clergy, soldiers, magistrates, gentlemen, and men of the general mass, that his system would bring down upon him and his followers the unmitigated vengeance of the persecuting hierarchy. His was no partially reforming system; it did not object to this or that dogma, this or that ceremony in the state religion, but it assailed, root and branch, state religion itself. It was a system peculiarly odious to priests, because it was an entirely disinterested one, for it went even to declare that nothing should be received for preaching, where it could be at all dispensed with, nothing in any case without the consent of the people. The state clergy saw, that if it succeeded, priestcraft was gone for ever: royalty, on its restoration, saw that it would lop off the right arm of despotism—craft paid to preach the divine right of kings, and passive obedience of the people. But Fox and his friends were prepared to speak, write, and suffer for it. He himself traversed a great part of the kingdom, visited America and Holland, holding immense meetings in the open air, and addressed many letters to various princes and people in power on its behalf. Barclay delineated its features in his celebrated "Apology for the true Christian Divinity." Penn wrote boldly for it, and spoke boldly for it, too, on his trials, especially that with William Mead at the Old Bailey, an account of which has often been reprinted, as a splendid instance of the vindication of trial by jury. Anthony Pearson, who had been a justice of the peace, published his "Great Case of Tithes," in which all the evils and and-Christianity of the tithe system were duly exposed. Thomas Lawson wrote, "A Mite in the Treasury," and "The Call, Work, and Wages of the Ministers of Christ and of Antichrist," two most spirited and able expositions of political religion. Elwood wrote his interesting life, abounding with scenes of imprisonment and patient endurance for his principles. Besse compiled, from official documents of the Society of Friends, a work of everlasting condemnation to the priests of the church of England; and Sewell wrote the "History of the Society" at large, a work declared by Charles Lamb to be worth all other ecclesiastical history put together. In these and other works they asserted those great principles of religious freedom now so generally adopted, and for these they suffered. Seeing clearly how a royal religion disturbed and oppressed the real church of Christ, how it neutralised all its benign doctrines, they determined, cost what it would, to hold no communion with it. They would neither marry at its altars, nor bury in its soil, and for this their dead were torn out of their graves by the parish priests and their minions; and they were not only heavily fined and imprisoned for marrying at their own chapels, but their children were declared illegitimate. At Nottingham, in 1661, an attempt was made by a public trial to disinherit some orphans on this ground, but the worthy old judge Archer brought Adam and Eve as precedents, and declared that their taking each other in marriage in the presence of God was valid, and if those children were illegitimate, then we were all so. On this singular decision the marriages of Friends were recognised and made legal. But had it been otherwise, such was the sturdy firmness of the Friends, that they would have suffered loss of both property, liberty, and life, to the last man, sooner than concede an iota to this unjust system; and the whole fury of the executive power was let loose upon them. They were given up a prey to vindictive parsons, and ignorant, priest-ridden justices of the peace, and to the whole greedy rabble of informers, constables, and the lowest refuse of society.

The history of their full extent of persecutions belongs to a later period; but the rise and principles of this society demand a notice in the religious history of this period as one of the most important events of any age. Those principles—their effect, or field of influence—are not to be measured by the limited growth of the society which first promulgated them. Like many other bodies out of which great principles have sprung, it has become, as it were, fossilised, retaining the form, and even the reverence of the original body; but the principles themselves are the principles of Christianity, coextensive with the universe in their action on spiritual life. It was the mission of Fox to liberate them from the conventional forms in which outward and worldly motives had imprisoned them, to sweep away all the cobwebs of school and state sophistry from them, and to recall the conviction of man to them in all their simple and sublime beauty. The puritans in general had made little progress in the comprehension of religious freedom; what they claimed themselves they were ready to withhold from others. Cromwell and the independents made a great advance, yet withheld this liberty from catholics and episcopalians; but Fox demonstrated that the liberty of the Gospel was the equal birthright of all men. All these religious reformers were ready to permit or become themselves a state church. Fox reminded them that the "Kingdom of Christ was not of this world;" that when they had rendered to Caesar the things that are Caesar's, civil support and obedience, they must render to God the things which are God's, the rights of conscience, and the independence of his church. For all the civilising and angelising influences of religion—resistance to slavery, oppression, war, priestcraft, world-worship, and mammon-worship—which are the divine and eternal essence of the Gospel, the philosophy and the theology of George Fox asserted the independence and universality, and these principles, now adopted into nearly all creeds, are silently but perceptibly at work to leaven the whole mass of society, and in the course of ages to throw down every tyranny, every cruelty, every abomination, on every side of the globe.

PROGRESS OF THE ARTS, MANUFACTURES, AND COMMERCE.

In the reigns of James and Charles this country neither maintained the reputation of our navy acquired under Henry VIII. and Elizabeth, nor made great progress in foreign commerce. The character of James was too timid for maritime or any other war, and when he was forced into action it was only to show his weakness. He put to death the greatest naval captain of his time, Raleigh, who, if well employed by him, might have made him as much respected at sea as was Elizabeth. Yet he built ten ships of war, and for some years spent thirty-six thousand pounds a year on the navy. The largest ship which had yet been built in England was built by him, which, however, was only fourteen hundred tons. As for commerce, he was too much engaged in theological disputations, in persecution of papists, wrangling with his parliaments, and following his hawks and hounds, to think of it, and consequently there were every fresh session grievous complaints of the decay of trade. The Dutch were fast engrossing both the commerce and the carrying trade of this country. During this reign they traded to England with six hundred ships, and the English traded to Holland with sixty.

The naval affairs of Charles were quite as inglorious as those of his father. As James beheaded the best admiral of England, Charles chose for his the very worst in Europe, and the disgrace of Buckingham's expedition to the Isle of Rhé was the consequence. Charles's contests with his parliaments, which terminated only with his life, destroyed all chance of his promotion of our naval ascendancy, and of the cultivation of commerce. All this was wonderfully changed by the vigorous spirits of the commonwealth. The victories of Blake, by which the naval greatness of Holland and Spain were almost annihilated, raised the reputation of the British arms at sea as well as on land to the first place in the civilised world. St. John was no sooner despatched by the parliament to the Hague as ambassador, than, perceiving the immense advantage which Holland drew from being the great carriers of Europe, he drew and got passed the celebrated Navigation Act, which, providing that no produce of Africa, Asia, or America, nor of any English colony should be imported into England except in English ships, and that the manufactures or merchandise of no country in Europe should be imported except in English ships, or the ships of the nation where they were produced, at once transferred an enormous amount of maritime business to this country.

Sir Walter Raleigh, in a treatise on the comparative commerce of England and Holland, endeavoured to draw the attention of James I. to the immense advantages that the Dutch were drawing from our neglect. He showed that whenever there was a time of scarcity in England, instead of sending out our ships and supplying ourselves, we allowed the Dutch to pour in goods and reap the advantage of the high prices; and he declared that in a year and a half they had taken from Bristol, Southampton, and Exeter alone, two hundred thousand pounds, which over merchants might as well have had. He reminded the king that the most productive fisheries in the world were on the British coasts, yet that the Dutch and people of the Hanse Towns came and supplied all Europe with their fish to the amount of two million pounds annually, whilst the English could scarcely be said to have any trade at all in it. The Dutch, he said, sent yearly a thousand ships laden with wine and salt, obtained in France and Spain, to the north of Europe, whilst we, with superior advantages, sent none. He pointed out equally stinking facts of their enterprise in the timber trade, having no timber themselves; that our trade with Russia, which used to employ a large number of ships, had fallen off to almost nothing, whilst that of the Dutch had marvellously increased. What, he observed, was still more lamentable—we allowed them to draw the chief profit and credit even from our own manufactures, for we sent our woollen goods, to the amount of eighty thousand pieces, abroad undyed, and the Dutch and others dyed them, and reshipped them to Spain, Portugal, and other countries as Flemish baizes, besides netting a profit of four hundred thousand pounds annually at our expense. Had James listened to the wise suggestions of Raleigh, instead of destroying him, and listening to such silly, base minions as Rochester and Buckingham, our commerce would have shown a very different aspect.

It is true that some years after James endeavoured to secure the profit pointed out by Raleigh from dyed cloths; but instead of first encouraging the dyeing of such cloths here, so as to enable the merchants to carry them to the markets in the South on equal or superior terms to the Dutch, he suddenly passed an act prohibiting the export of any undyed cloths. This the Dutch met by an act prohibiting the import of any dyed cloths into Holland; and the English not producing an equal dye to the Dutch, thus lost both markets, to the great confusion of trade; and this mischief was only gradually overcome by our merchants beginning to dye their yarn, so as to have no undyed cloth to export, and by improving their dyes.

During the reign of James commercial enterprise showed itself in the exertions of various chartered companies trading to distant parts of the world. The East India Company was established in the reign of Elizabeth, the first charter being granted by her in 1600. James was wise enough to renew it, and it went on with various success, ultimately so little in his time, that at his death it was still a doubtful speculation; but under such a monarch it could not hope for real encouragement. In its very commencement he granted a charter to a rival company to trade to China, Japan, and other countries in the Indian seas, in direct violation of the East India Company's charter, which so disgusted the company, as nearly to have caused them to relinquish their aim. In 1613 they obtained a charter from the Great Mogul to establish a factory at Surat, and the same year they obtained a similar charter from the emperor of Japan. In 1615 Sir Thomas Roe went as ambassador from England to the Great Mogul, and resided at his court for four years. By this time the company had extensively spread its settlements. It had factories at Acheen, Zambee, and Tekoa, in Sumatra; at Surat, Amadavad, Agra, Azmere, and Burampore, in the Mogul's territories; at Firando, in Japan; at Bantam, Batavia, and Japara, in Java; and others in Borneo, the Banda Islos, Malacca, and Siam, in the Celebes; and at Masulipatam and Petapoli, on the Coromandel coast; and at Calicut, the original settlement of the Portuguese on the coast of Malabar. Their affiars were, in fact, extremely flourishing. and their stock sold at 203 per cent.; but this prosperity awoke the jealousy of the Dutch, who carried on a most profitable trade with Java and the Spice Islands, and in spite of a treaty concluded betwixt the two nations in 1619, the Dutch governor-general attacked and took from the company the islands of Lantore and Pido Rangoon. This was only the beginning of their envious malice, for in 1623 they committed the notorious massacre of the English company at Amboyna, and expelled the English out of all the Spice Islands. Had this occurred in Cromwell's days, they would soon have paid a severe retribution; but James was just then anxious to secure the aid of the Dutch in restoring his son-in-law, the count palatine, and these atrocities were quietly smoothed over and left unavenged. The consequence was, that the affairs of the company fell into a most depressed condition, and though in 1616, when their stock was worth 200 per cent., they had raised a new stock of one million six hundred and twenty-nine thousand and forty pounds, which was taken by nine bundled and fifty-four individuals, principally of the higher aristocracy, at the close of James's reign the stock had fallen half its value.

Charles did not prove a more far-sighted or just patron of the India Company than his father. In 1031 they managed to raise a new stock of four hundred and twenty thousand pounds, but whilst they were struggling with the hostilities of their rivals, the Dutch and Portuguese, the king perpetrated precisely the same injury on them that his father had done, by granting a charter to another company, which embroiled them with the Mogul and the Chinese, causing the English to be entirely expelled from China, and injuring the India Company to a vast extent. The civil war in England then prevented the attention of the government being directed to the affairs of this important company. At the end of Charles's reign the company's affairs were at the worst, and its trade appeared extinct. In 1649, however, the parliament encouraged the raising of a new stock, which was done with extreme difficulty, and only amounted to one hundred and ninety-two thousand pounds. But in 1654, the parliament living humbled the Dutch, compelled them to pay a balance of damages of eighty-five thousand pounds and three thousand six hundred pounds to the heirs of the murdered men at Araboyna. It required years, however, to revive the prosperity of the company, and it was only in 1657 that, obtaining a new charter from the protector, and raising a new stock of three hundred and seventy thousand pounds, it rose again into vigour, and traded successfully till the restoration.

During this period, too, the incorporated companies—Turkey Merchants or the Levant Company, the Company of Merchant Adventurers trading to Holland and Germany, the Muscovy Company trading to Russia and the North, where they prosecuted also the whale fishery—were in active operation, besides a great general trade with Spain, Portugal, and other countries. The Tm-key Merchants carried out to the Mediterranean our cloths, lead, tin, spices, indigo, calicoes, and other Indian produce brought home by our East India Company; and they imported thence the raw silks of Persia and Syria, galls from Aleppo, cotton and cotton yarn from Cyprus and Smyrna; drugs, oils, and camlets, grograms, and mohairs, of Angora. In 1652 we find coffee first introduced from Turkey, and a coffee-house set up in Cornhill. On the breaking out of the civil war, the Muscovy Company were deprived of their charter by the czar, because they took part with the parliament against their king and the Dutch adroitly came in for the trade.

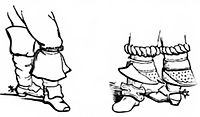

These great monopolies of foreign trade were supposed to be necessary to stimulate and protect our commerce; but the system of domestic monopolies which were most destructive to enterprise at home, which had arrived at such a height under Elizabeth, was continued by both James and Charles to the last, notwithstanding the constant outcries against them, and their being compelled, ever and anon, by public spirit to make temporary concessions. The commerce of England was now beginning to receive a sensible increase by the colonies which she had established in America and the West Indies. One of the earliest measures of James was the founding of two chartered companies to settle on the coasts of North America. One called the London Adventurers, or South Virginia Company, was empowered to plant the coast from the 34th to the 41st degree, which now includes Maryland, Virginia, and North and South Carolina. The other, the company of Plymouth Adventurers, were authorised to plant all from the 41st degree to the 45th of north latitude, which now includes the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, and New England. In 1612 a settlement was made in Bermuda. The state of New England was founded by the planting of New Plymouth in 1620, and about the same time the French were driven out of Nova Scotia, and the island of Barbadoes was taken possession of; and within a few years various other West India islands were secured and planted. James granted all the Caribbee Isles to his favourite, James Hay, earl of Carlisle, and the grant was confirmed by Charles, who also granted to Robert Heath and his heirs all the Bahama Isles and the vast territory of Carolina, including the present North and South Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, and the south of Louisiana. In 16;12 Charles also granted the present Maryland to lord Baltimore, a catholic, which became the refuge of the persecuted catholics in England, as the New England states did of the puritans.

These immense territories were gradually peopled by the victims of persecution and the victims of crime. According as the storm of religious persecution raged against the catholics, the puritans, or the episcopalians and royalists, they got away to New England, Maryland, or Virginia. By degrees the Indians were driven back, and cotton, tobacco, and in the West Indies the sugar cane became objects of cultivation. James abominated tobacco, and published his "Counterblast" against it, laying serious restrictions upon its growth; but as the high duties imposed upon it proved very profitable to the revenue, gradually these restrictions were relaxed, and all cultivation of it at home was prohibited in favour of the colonies, and has continued so ever since. The Dutch had managed to engross the carrying trade under James and Charles to our American and West India colonies, having a strong position at New Amsterdam, now New York; but of this the parliament, after the revolution, deprived them in 1646, and extended that regulation to all our foreign trade by the famous Navigation Act 1651. In 1650 Cromwell's conquest of Jamaica completed our power in the West Indies.

The growth of our commerce was soon conspicuous by one great consequence, the growth of London. It was in vain that both James and Charles issued repeated proclamations to prohibit fresh erections of houses, and to order the nobility and gentry to live more on their estates in the country, and not in London, in habits of such extravagance, and drawing together so much loose company after them. From the union of the crowns of Scotland and England, this rapid increase of the metropolis, so alarming to these kings, was more than ever visible. When James came to the throne in 1603, London and Westminster were a mile apart, but the Strand was quickly populated by the crowds of Scots that followed the court; and though St. Giles's-in-the-Fields was then a distinct town, standing in the open country, with a very deep and dirty lane, called Diury Lane, running from it, to the Strand, before the civil wars it had become united to London and "Westminster by new erections in Clare Market. Long Acre, Bedfordbury, and the adjoining neighbourhood. Anderson, in his "History of Commerce," gives us some curious insight into this part of London at this period. "The very names of the older streets about Covent Garden," he observes, "are taken from the royal family at this time, or in the reign of Charles II., as Catherine Street, Duke Street, York Street. Of James and Charles the I.'s time, James Street, Charles Street, Henrietta Street, &c., all laid out by the great architect, Inigo Jones, as was also the fine piazza there, although that part where stood the house and gardens of the duke of Bedford is of much later date, namely, in the reigns of king William and queen Anne. Bloomsbury, and the streets at the Seven Dials, were built up somewhat later, as also Leicester Fields, since the restoration of Charles II., as also almost all of St. James's and St. Anne's parishes, and a great part of St. Martin's and St. Giles's. I have met with several old persons in my younger days who remembered that there was but a single house, a cake-house, between the Mews-gate at Charing Cross and St. James's Palace-gate, where now stand the stately piles of St. James's Square, Pall Mall, and other fine streets. They also remembered the west side of St. Martin's Lane to have been a quickset hedge; yet High Holborn and Drury Lane were tilled with noblemen's and gentlemen's houses and gardens almost a hundred and fifty years ago. Those five streets of the south side of the Strand, running down to the river Thames, have all been built since the beginning of the seventeenth century upon the sites of noblemen's houses and gardens, who removed further westward, as their names denote. Even some parts within the bare of the city of Lounou remained unbuilt within about a hundred and fifty years past, particularly all the ground between Shoe Lane and Fewters, now Fetter Lane, so called, says Howell in his Londonopolis, from Fewters, an old appellation of idle people loitering there, as in a way leading to gardens; which, in Charles I.'s reign, and even some of them since, have been built up into streets, lanes, &c. Several other parts of the city have been rendered more populous by the removal of the nobility to Westminster, on the sites of whose former spacious houses and gardens whole streets, lanes, and courts have been added to the city since the death of queen Elizabeth."

The extension of the metropolis necessitate<l the introduction of hackney coaches, which first began to ply, but only twelve in number, in 1625. In 1634 sedan-chairs were introduced to relieve the streets of the rapidly increased number of hackney-coaches, and other carriages; and in 1635 a post-office for the kingdom was established, a foreign post having been for some years in existence. Li 1653 the post was farmed for ten thousand pounds a year.

NATIONAL REVENUE, MONEY, AND COINAGE.

The annual revenue of James I. has been calculated at about six hundred thousand pounds, yet he was always poor, and died leaving debts to the amount of three hundred thousand pounds. He was prodigal to his favourites, and wasteful in his habits. He left the estates of the crown, however, better than he found them, having raised their annual income from thirty-two thousand pounds to eighty thousand pounds, besides having sold lands to the amount of seven hundred and seventy-five thousand pounds. He still prosecuted the exactions of purveyance, wardship, &c., to the great anoyance of his subjects. On the occasion of his son being made a knight, he raised a tax on every knight's fee of twenty shillings, and on every twenty pounds of annual rent from lands held directly of the crown, thus raising twenty-one thousand eight hundred pounds; and on the marriage of his daughter Elizabeth to the prince Palatine, he levied an aid of twenty thousand five hundred pounds, the last of these odious impositions which were demanded. The customs on his coming to the throne brought in one hundred and twenty-seven thousand pounds a year; but towards the end of his reign, showing the great increase of commerce, they amounted to one hundred and ninety thousand pounds a year. But this was the tonnage and poundage which was so hateful to the nation, and which James had greatly augmented by his own act and deed; an encroachment which caused parliament to refuse to his son Charles the usual grant of those duties for life; and his persistence in levying them, in spite of parliament, was one of the chief causes of his quarrel with that body, and the loss of his crown.

James was also a great trader in titles of nobility. His price for a barony was ten thousand pounds, for the title of viscount, twenty thousand pounds, and for that of an earl, thirty thousand pounds. He also invented the new title of baronet, and raised two hundred and twenty-five thousand pounds by it, at the rate of one thousand and ninety-five pounds each baronetcy. From so dignified a source do many of our aristocracy derive their honours.

Charles, though he was driven to such fatal extremities to extort money from his subjects, Ls calculated to have realized the enormous revenue from 1637 to 1611 inclusive, of eight hundred and ninety-five thousand pounds, of which two hundred and ten thousand pounds arose from ship-money and other illegal sources. Both he and his father dealt in wholesale monopolies to their courtiers and others, the profits of which were so embezzled by those greedy and unprincipled men, that Clarendon says that of two hundred thousand pounds of such income in Charles's time, only one thousand five hundred pounds reached the royal treasury. Charles raised two hundred thousand pounds in 1626 by a forced loan, and another hundred thousand by exacting the fees or compensation for exemption from the assumption of knighthood by every person worth forty pounds a year.

The income and expenditure of the commonwealth are stated to have far exceeded those of any monarch who ever sate on the throne of these realms, and to have been not less than four million four hundred thousand pounds per annum. The post-office, as already stated, brought in ten thousand pounds per annum. A singular tax, called the Weekly Meal, or the price of a meal a week from each person, produced upwards of one hundred thousand pounds a year, or six hundred and eight thousand four hundred pounds in the six years during which it was levied. There was a weekly assessment for the support of the war, which rose from thirty-eight thousand pounds to one hundred and twenty thousand pounds per week, which was continued as a land-tax under the protectorate, producing from 1640 to 1659 no less than thirty-two million one hundred and seventy-two thousand three hundred and twenty-one pounds. The excise also owes its origin to this period, and produced, it is said, five hundred thousand pounds a year. Large sums were realised by the sales of crown and church lands. From the sale of crown lands, parks, &c., one million eight hundred and fifty-eight thousand pounds; from the sale of church lands, ten million pounds; from sequestration of the revenue of the clergy for four years, three million five hundred thousand pounds; eight hundred and fifty thousand pounds from the incomes of office sequestered for the public service; four million five hundred thousand pounds from the sequestration of private estates or compositions for them; one million pounds from compositions with delinquents in Ireland; three million five hundred thousand pounds from the sale of forfeited estates in England and Ireland, &c. The ministers and commanders are asserted to have taken good care of themselves. Cromwell's own income is stated at nearly two million pounds, or one million nine hundred thousand pounds; namely, one million five hundred thousand pounds from England, forty-three thousand pounds from Scotland, and two hundred and eight thousand pounds from Ireland. The members of parliament were paid at the rate of four pounds a week each, or about three hundred thousand pounds a year altogether; and Walker, in his "History of Independency," says that Lenthall, the speaker, held offices to the amount of nearly eight thousand pounds a year; that Bradshaw had Eltham Palace, and an estate of one thousand pounds a year, as bestowed for presiding at the king's trial; and that nearly eight hundred thousand pounds were spent on gifts to adherents of the party. As these statements, however, are those of their adversaries, they no doubt admit of ample abatement; but after all deduction, the demands of king and parliament on the country during the contest, and of the protectorate in keeping down its enemies, must have been enormous. Notwithstanding this, the rate of interest on money continued through this period to decline. During James's reign it was ten per cent.; in 1624, the last year of his reign, it was reduced to eight per cent., and in 1651 was fixed by the parliament at six per cent., at which rate it remained.

Coin of the value of Fifteen Shillings of the Reign of James I.

Coin of the value of Thirty Shillings of the Reign of James I.

James issued various coinages. Soon after his accession he issued a coinage of gold and one of silver. The gold was of two qualities. The first of twenty-three carats three and a half grains, consisting of angels, half-angels, and quarter-angels; value ten shillings, five shillings, and two-and-sixpence. The inferior quality, of only twenty-two carats, consisted of sovereigns, half-sovereigns, crowns, and half-crowns. His silver coinage consisted of crowns, half-crowns, shillings, sixpences, twopences, pence, and halfpence. These gold coins, being of more value than that amount of gold on the continent, were rapidly exported, and the value of the finest gold was then raised from thirty-three pounds ten shillings to thirty-seven pounds four shillings and sixpence. The next coinage at this value consisted of a twenty-shilling piece called the unity, ten shillings called the double crown, five shillings or the Britain crown, four shillings or the thistle crown, and two-and-sixpence or half-crown. This value of the gold was not found high enough, and the next year, a fresh coinage, it was valued at forty pounds ten shillings, and consisted of rose-rials of thirty shillings each, spur-rials fifteen shillings, and angels at ten shillings each. But gold still rising in Value, in 1011, the unity was raised to twenty-two shillings, and the other coins in proportion. In the next year there was a great rise in gold, and in 1612 James issued fresh twenty-shilling, ten-shilling, and five-shilling pieces, which became known as laurels, from the king's head being wreathed with laurel. The unity and twenty-shilling pieces were termed hood pieces. Besides the royal coinage, shopkeepers and other retailers put out tokens of brass and lead, which in 1610 were prohibited, and the first copper coinage in England, being of farthings, was issued.

Crown of Charles I.

Shilling of the Protector.

The coins of Charles were, for the most part, of the same nature as those of his father. During his reign silver rose so much in value that it was melted down and exported to a vast extent. Though betwixt 1630 and 1643 some ten million pounds of silver were coined, it became so scarce that people had to give a premium for change in silver. In 1637 Charles established a mint at Aberystwith, in Wales, for coining the Welsh silver, which was of great value to him during the war. From 1628 to 1640 Nicholas Briot, a Frenchman, superintended the cutting of the dies, instituted machinery for the hammer in coining, and his coins were of remarkable beauty. Charles erected mints at most of his head-quarters during the war, as Oxford, Shrewsbury, York, and other places, the coiners and dies of Aberystwith being used, and these coins are distinguished by the prince of Wales's feathers. Many of these coins are of the rudest character; and besides these there were issued obsidional or siege pieces, so called from the besieged castles where they were made, as Newark, Scarborough, Carlisle, and Pontefract. Some of these are mere bits of silver plate with the rude stamp of the castle on one side and the name of the town on the other. Others are octagonal, others lozenge-shaped, others of scarcely any regular shape.

William Shakespeare.

The commonwealth at first coined the same coins as the king, only distinguishing them by a P for parliament. They afterwards adopted dies of their own, having on one side a St. George's cross on an antique shield encircled with a palm and laurel, and on the other two antique shields, one bearing the cross and the other the harp, surrounded by the words God with us. Their small silver coins had the arms only without any legend. Those were all parliament money, but there were half-crowns, shillings, and sixpences with milled edges. The coins of the protectorate boar the head of Cromwell laurelled like a Cæsar, and round the head, Olivar. D. G. R. P. Amj. Sco. Hib. etc. Pro. On the reverse a shield, having in the first and fourth quarters St. George's cross, in the second St. Andrew's, in the third a harp, and in the centre a lion rampant on an escutcheon— Cromwell's own arms. This shield supported a royal crown. The circumscription was Pax quxrilur Bello, and the date 1656, or 1658. These coins were from the dies of Symonds, and were superior to any which had appeared since the time of the Romans. The coins of the commonwealth were the same for Ireland and Scotland as for England. This was not the case in the reigns of James and Charles, which, though bearing the same arms, had generally a very different value. For Ireland James coined silver and copper money of about three-quarters of the value of the English, and called in the base coinage used by Elizabeth in the time of the rebellion. Charles only coined some silver in 1641, during the government of lord Ormond, and therefore called Ormonds. Copper halfpence and farthings of that period are supposed to have been coined by the rebel papists of 1642.

AGRICULTURE AND GARDENING.

In these arts the English were still greatly excelled by their neighbours the Dutch and Flemings. Towards the latter part of this period our country began to imitate those industrious nations, and to introduce their modes of drainage, their roots and seeds. In 1652 the advantage of growing clover was pointed out by Bligh, in his "Improver Improved," and Sir Richard Weston recommended soon after the Flemish mode of cultivating the turnip for winter fodder for cattle and sheep. Gardening was more attended to, and both culinary vegetables and flowers were introduced. Samuel Hartlib, a Pole, who was patronised by Cromwell, wrote various treatises on agriculture, and relates that in his time old men recollected the first gardener who went into Surrey to plant cabbages, cauliflowers, and artichokes, and to sow early peas, turnips, carrots, and parsnips. Till then almost all the supply of these things in London was imported from Holland and Flanders. About that time, however, 1650, cherries, applet, pears, hops, cabbages, and liquorice were rapidly cultivated, and soon superseded the necessity of importation; but Hartlib says onions were still scarce, and the supply of stocks of apple, pear, cherry, vine, and chestnut trees was difficult from want of sufficient nurseries for them. There was a great tendency to cultivate tobacco, but that, as we have seen, was stopped in favour of the colonies. There was a zealous endeavour to introduce the production of raw silk, and mulberry trees and silk worms were introduced, but the abundant supply of silk from India, and the perfection of the silk manufactured in France, rendered this scheme abortive,—and to this circumstance we owe the general diffusion of the mulberry tree in this country. In Markham's "Farewell to Husbandry," published in 1620, the various agricultural and gardening implements may be seen.

LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND THE FINE ARTS.

Whilst James was hunting and levying taxes without a parliament, and Charles was in continual strife with his people for unconstitutional power and revenue, literature and art were still at work, and producing or preparing some of the noblest and choicest creations of genius. Shakespeare and Milton wore the great lights of the age; but around and beside them burned a whole galaxy of lesser, but not less exquisite, luminaries, whose selected beauties are just as delightful now as they were to their contemporaries. The names of this period, to which we still turn with admiration, reverence, and affection, are chiefly Shakespeare, Milton, Bacon, Marlowe, Massinger, Webster, Selden, Herrick, Herbert, Quarles, Bunyan, Bishop Hall, Hales, Chillingworth, Jeremy Taylor, Raleigh, Sir Thomas Browne, Burton (of the "Anatomy of Melancholy"), and Drummoud, of Hawthornden. But there are numbers of others, more unequal or more scholastic, to whose works we can occasionally turn, and find passages of wonderful beauty and power.

As we come first to Shakespeare, who figured largely on the scene in the days of queen Bess, and whose poetry we have already renewed, we may take the drama of this period also in connection with him. A formal criticism on Shakespeare would be worse than superfluous—it would be almost an insult to any reader of the present day, who is as familiar with his character and his beauties as he is with his Bible, and perhaps, in many cases, much more so. There are whole volumes of comment on this greatest of our great writers both in this language and others. The Germans have written volumes on his genius and works, and pride themselves on understanding him better than ourselves. They cannot believe but that he must have been in Germany, to represent so completely their feelings and philosophies; and, were there any obscurity about his birthplace, would certainly claim him. The Scandinavians equally venerate him, and have an admirable translation of his dramas. Even the French, the tone and spirit of whose literature are so different from ours, have, of late years, began to comprehend and receive him. The fact is, Shakespeare's genius is what the Germans term spherical, or many-sided. He had not a brilliancy in one direction only, but he seemed like a grand mirror, in which is truly reflected every image that falls on it. Outward nature, inner life and passion, town and country, all the features of human nature, as exhibited in every grade of life—from the cottage to the throne—are in him expressed with a truth and a natural strength, that awake in us precisely the same sensations as nature itself. The receptivity of his mind was as quick, as vast, as perfect, as his power of expression was unlimited. Every object once seen appeared photographed on his spirit, and he reproduced these lifelike images in new combinations, and mingled with such an exuberance of wit, of humour, of delicious melodies, and of exquisite poetry, as has no parallel in the wide range of literature, including all ages and all countries. The learned have always been astonished that he could be all this without an academic education, as if the academy of God's universe did not include all lesser colleges, and as if God needed lectures and masters to instruct those whom he chooses to inform himself, and to produce as his elect and peculiar oracles.