Face to Face with the Mexicans/Chapter 12

CHAPTER XII.

MORE ABOUT THE COMMON PEOPLE.

The Silent Aztec Child of the Sun.

silence of dead centuries

That lie entombed on yonder hills

Is his. These dreamful poppy seas

Wave on; and all their languor fills

The land; he lists, as if he heard

God speak through some still gorgeous bird.

His babes about; the golden morn

Strides godlike down the lofty hill:

His wife and daughter grinding corn—

"Two women grinding at a mill."

Oh, mystery! This sun of old

Was god! was god! and ample gold.

His golden hills had flocks of snow,

His valley fields had fat increase.

He saw his white sails fill and blow

By restful isles of flower seas.

The wood-dove sang his ceaseless loves—

His harshest notes this soft wood dove's.

The Spaniard holds his lands! Upon

His fields, his flocks, his hold is tight!

But, oh, this glorious golden dawn,

The golden doors that close at night.

His gold-hued babes, her russet breast

Are his! The world may have the rest.

A TYPICAL INDIAN VILLAGE.

in the life and character of these Indians. Vast estates were once theirs. Their flocks and herds roamed at large upon the plains of their fathers. The blue sky, the shining lakes, the forests and mountains belonged to these children of the sun. To-day they are in dire poverty; the lands once tilled by their vassals they now till for others. They are the patient burden-bearers of this once grand Indian Empire. If their yoke is not easy, nor their burden light, we hear no complaint.

If we compare them with our North American Indians, we are struck with the contrast presented. At one fell blow the Aztecs were conquered, their spirit of independence crushed out. We have contended with our Indians for more than two hundred years. They have scalped and murdered the white man and burned his home, but as yet we have not been able to grapple the subject.

He retreats, we follow, and so long as he is not completely subdued, so long will he continue to pursue his own barbarous course. He feels the time coming when the white man will possess his all—when not a foot of land, and perhaps but a mere remnant of his traditions, will be left to him. While he can, he will carry his revenge in his own hand. He wants nothing—cares for nothing—if he has not his hunting-ground. He has no local habitation and no handicraft to amuse and divert him from the thought that each day provides for itself; and he must keep his arrows sharp, his flint and steel in readiness, to meet the pale faces that pursue him.

The Mexican Indian leads a peaceful life and remains on the same soil, even though it be his no longer. He is satisfied, feeling the worst is past and perhaps a better day in store for him. Shut up in his hut of adobe or palm, without either light or air, the chase and the camp have no charms for him. It troubles him little that he belongs to a conquered race. The independence of Mexico has not yet accomplished much for these people, yet they are content. Would that the great question of our own Indians might be settled, and that they could regulate their lives in as useful and peaceful a manner as their dusky-hued brethren in the land of the Montezumas! The Mexican Indian is by inherent custom an agriculturist, and notwithstanding the fact that the conqueror imposed upon him burdensome and distasteful labors—among them that of mining—he at the first opportunity returned to his favorite vocation, to which he still adheres at the present day.

"According to what you declare," said he, "of the place whence you came, which is toward the rising sun, and of the great Lord who is your King, we must believe that he is our natural Lord."

Without being inventive, they are great imitators and marvelously ingenious in the construction of the infinite variety of curiosities of the country.

Straw, wax, wood, marble, grass, hair and mother earth are all successfully treated by these dexterous brown fingers. True to the life are these imitations, even the tiniest wax figures not more than an inch in length, representing venders of vegetables, fruits, or other commodity. But to me the most wonderful are the productions of the Guadalajara Indians in clay and glazed pottery. Of the latter, their pitchers, vases, water-jugs, animals and toys of all sorts are beautiful, while in the former an extraordinary artistic conception is evinced. In an incredibly short space of time they will model for you a life-like bust, either from the life or from a photograph. The strength of expression and fidelity to the subject are remarkable.

Their plumaje (feather-work) is delicate and artistic. Cortez and his men were much interested in the cloth woven of feathers, so intricate, multicolored and beautiful. They no longer manufacture feather cloth, but expend their skill in this line in the representation on cards of all kinds of animals, birds and landscapes.

On feast-days these ingenious people have their stalls on the Zocalo, with their street agents, and business is animated. Each one of these days finds still another variety of toys, and some of them are indeed laughable. For the 1st of November they have cross-bones and skulls, funeral processions (calaveras in wood), and death's-heads in imitation bronze, with glaring eyeballs and grinning teeth. All these are arranged on a miniature table, with a small bottle for pulque, and on one corner a cake or piece of bread of the kind the dead may be supposed to like.

Their rag figures and dolls are a comical invention. They make baskets with taste and ingenuity, from the size of a thimble to one or more yards in height. They excel in frescoing. They manipulate tissue-paper into decorative forms, and in numberless ways display aptness and imitative skill.

In brief, these productions of their natural ingenuity would require, in other countries, years of patient toil and study, if they could even then be reproduced. But I have been told that any attempt to educate them in their peculiar branches of art would be the means of losing their entire knowledge. This wonderful skill is purely the result of an artistic tendency—a faculty handed down from his ancestors. But, as may be seen in other avenues of business in this land of rest and romance, they work on insignificant articles for days or weeks, seemingly to the exclusion of all else, and then dispose of them for a mere trifle.

The Indian voice is soft and low, almost flute-like in its sweetness, in this quality contrasting with the shrill tones frequently heard in the higher ranks of society. Their step is light, even cat-like, in its softness—a characteristic of all classes, regardless of station.

On dias de santo and other feast-days, outdoor gambling of every description is indulged in by this class, while bullfights and pulque-drinking constitute their principal pleasures.

The love for spectacular display is also a predominating characteristic with them. It is shown in the pleasure taken in sky-rockets and all pyrotechnics, especially if accompanied by a band of music.

Their taste also finds expression in the universal love of flowers. Not only are the humblest homes embellished with such gay and gorgeous flowers as would constitute the choicest treasures of a northern hot-house, but in the streets and markets, edibles and other commodities are exposed for sale side by side with them, and for a tlaco or medio one may buy a lovely bouquet.

They are also great admirers of pictures, and groups may be seen any day in the principal cities, gazing intently on those exhibited in the windows. But I have caught glances, pathetic to the last degree, as they peered through windows where shoes and stockings were exposed for sale.

The laboring class rise early and work late, rarely going home before the close of the day. Their wives bring them their dinner, and the whole family sit down to the bread of contentment upon a curb-stone.

The large number of unoccupied and non-producing among the common people may to some extent be accounted for by the bounty of nature and the cheapness and great variety of food-products. It is little wonder that they have no ambition to rise higher in the social scale, when the luxuries of life, without the least adulteration, may be obtained for a mere song. The idle, indigent and thriftless have equal advantages in the food they eat, with the toiling and industrious. The atole of all kinds, the barbecued meats, soups, beans and rice, together with the great variety and cheapness of fruits and vegetables, render their dietary one to be envied. From six to twelve cents will purchase a substantial and well-cooked meal, and it is an interesting event in one's experience to see the motley assemblage in the market place, and to hear their gay sallies at the mid-day meal; so that in many respects they have decided advantages, so far as relates to food, over even people of affluence in some parts of the United States.

The climate, also, brings its blessings to the poor. They may sleep in a house, if it can be afforded; if not, their lodging may be in the streets, the recesses of the churches, or any place that Morpheus may overtake them.

Clothing may be domestic or muslin, with a blanket or rebozo, and no special inconvenience is experienced. But, however poverty-stricken and wretched their condition, the women are always expert and canny with the needle. A woman with scarcely a change of raiment will embroider, crochet, and do plain and fancy sewing that would put to the blush our most dexterous needlewomen. She sits on the sidewalk from morn till eve, selling a basket of fruits, but not a moment does she lose from her stitching. One fact worthy of being chronicled is, that the common people are making a considerable effort toward advancement in learning to read and write, even while employed as servants in families. I saw several at the capital who, unaided, were studying Spanish one day and English the next.

Mexico has a population of about 10,000,000, of which one and a half are pure white—Americans, Germans, French, English and Spaniards—and two and a half mestizos—leaving about 6,000,000 of Indians.

It has been estimated that there are five hundred different dialects in the country. The Indians have, in the main, retained their own race and tribal characteristics. Spanish is the language of many of them, but numerous tribes are to be found who speak purely in their own tongue, and cling to their own traditions, dress, and to some extent, their own peculiar forms of religious worship, seldom intermarrying with others.

In the sixteenth century, according to Mexico á travers de los Siglos the types were classified as follows, and, barring the natural increase of population, they remain about the same to-day:

| Children of | Spaniards | born in | the country | are called | Creoles. | ||||

| ” | Spaniards | and | Indians | ” | Mestizos. | ||||

| ” | Mestizos | " | Spaniards | ” | Castigos. | ||||

| ” | Castigos | ” | Spaniards | ” | Españoles. | ||||

| ” | Spaniards | " | Negros | ” | Mulattos. | ||||

| ” | Mulattos | " | Spaniards | ” | Moriscos. | ||||

| ” | Negros}} | " | Indians | ” | Zambos. |

Occasionally race characteristics, after lying dormant for perhaps generations, crop out unexpectedly in families, causing quite a shock when they appear. A dark, or as is sometimes the case, black child makes its appearance, and this is called Salta atrás (a leap over several generations).

The mestizos are the handsomest, and the zambos must rest content with occupying the position of the ugliest and most unattractive of the races.

As to the real merits of this classification, it is not possible for me to speak. I only know how the various shades and complexions impressed me as a subject for study. The dark, olive-tinted types seized upon my fancy from the date of my advent into the country. I felt a deep and sympathetic interest in them, as being the more directly connected with the aborigines. In their quiet and humble manner I read the history of a conquered people. In these dark shades there exist at least two different types. The pale though dark, swarthy, bloodless face, with melancholy, expressionless eyes and dejected bearing, indicates the one, while the other, the type above all others pleasing and interesting to me, possesses a rich brown skin, with carmine cheeks and lips; glistening, white teeth, united with great, wondering, half-startled, luminous eyes, soft and shy as those of the gazelle. Even their forms and gait are different, the one thin and shambling, the other, plump, full-blooded, graceful and active. Their politeness and humility, even among the most ragged and degraded, are touching. This is not confined to their bearing toward superiors, but is also shown to each other.

The salute of the poorest to his bronze-colored compatriot as they pass, makes the air musical with their liquid Indian idiom. Their code of etiquette is expansive enough to cover that practiced in the grandest homes in our American cities. In this respect the wealthiest hacendado has no advantage over the humblest peon who toils for him a natural life-time. They are strictly careful never to omit the Don and Doña to each other, and "where you have your house," and "muy á su disposicion,"—terms synonymous with the higher classes—are in no way modified by the lower. Even their children are taught to say, on being asked their names, su criado de V. (your humble servant).

The talent for music is even more striking than that of the cultured higher classes. It is no unusual thing to hear every part of an air carried through in perfect harmony by full, rich, native voices, entirely ignorant of the first principles of the art which they so successfully practice.

The government is now doing a great work by granting pensions to all meritorious persons in the cultivation of any talent. I saw in the Conservatory of Music, in the capital, two Indian girls who had walked from Querétaro, a distance of one hundred and fifty miles, to present themselves as pupils in that admirable institution. I heard them sing selections from Italian opera, and the sweetness, strength, and range of their voices were far beyond the average, and produced a profound impression upon the audience.

The brass bands, with which travelers' ears are regaled everywhere in the country, are composed of this part of the population. It is no uncommon thing to see bands composed entirely of young boys, from twelve to eighteen years, who render the music in such a manner that a master from the Old World would find but little to criticise and much to commend.

Their music is of a sad, melancholy kind, even that danced or sung at their fandangoes. La Paloma is a universal favorite, and as they sing it, often their bodies and faces look as if it were an appeal to the Virgin or some of the saints, rather than an air for enlivenment or amusement. In this way the sentiment and deep-toned pathos in their natures find expression.

The large class of useless, lazy, indigent, ragged, and wretched objects in the streets of a Mexican city impresses the stranger that there is no good among them. But there is a large and industrious population possessing kindly and gentle impulses, the women practicing, as far as possible, the tender charities of the cultured higher classes.

Even the, Iepero, the representative of the very lowest and most degraded of the male element, assumes the extremes of two conditions. On the one hand, he has no compunctions of conscience in appropriating the property of another, nor does his moral nature shrink, perhaps, from plunging the deadly dagger into the back of his unsuspecting victim, while other vicious and ignoble traits are imputed to him; but, on the other hand, he has a heart and much of the sentimental and romantic instinct which invests him with many of the attractions of the bandit.

The most beautiful and distinctive female type of the common people is the China (Chena), familiarly known as the China poblana. With many added attractions she may be considered the counterpart of the French grisette. But the China has a rich and luxurious tropical order of beauty that is especially her own, with hands, arms, and feet that could not be excelled for artistic elegance by Praxiteles. She has the warmth of nature and faithful devotion which characterize

the artist's revenge

all Mexican women. Her peculiar costume, now rarely seen, possesses a semi-barbaric charm that interdicts all rivalry; but it will soon be a memory of the past, having given place in great measure to a more modern style.

The common people have, generally, a great dread of having their pictures taken. A sort of superstition haunts them that the process will deprive them of some part of their being, either corporal or spiritual. This dread was realized when the artist took her revenge on a curious crowd who had gathered so closely around us as to almost impede the manipulations of her pencil. I was constantly on the qui vive for some of my former mozos who had left me some years before to go to their families. I was certain on one occasion that I had found one of them, but he had risen from the rank of mozo to a cargador, with all the dignity and equipments of that station. When he entered the house where I was, on an errand, the resemblance to Miguel Rodriguez was so striking that I told him so, and begged him to allow himself to be sketched. But no sooner were the initial marks made upon the paper, than, looking on to examine the work, he became filled with unreasonable but not-to-be-combated terror, saying, perhaps the man he looked like had robbed me, and so, with the inevitable finger motion, and a "No, I cannot permit it!" turned and fled out of the room, down the steps, and up the street like a deer before the hounds.

In writing of this class, I have allowed them to speak for themselves, and surely no history is more reliable and complete than that related by the actors in the events recorded.

They are possessed of a certain amount of piquancy, as expressed in their peculiar dialect and idioms. With this there is united also a strong vein of humor, and they usually see a point as quickly as any people.

In consideration of the fact that they have but little education, their native shrewdness and intelligence are surprising. The most highly educated and enlightened cannot cope with them in the matter of barter and sale and the counting of money. By instinct they know just how, when, and where to strike the weak point of a stranger in any business transaction.

Americans are special objects of interest in this line. They always imagine that all Americans are possessed of boundless wealth.

The love of money is well developed, and the possibility of winning even a tlaco at gambling is sufficient to induce them to lose a whole night's sleep.

These people are made up of that mixed race of natives and whites called mestizos.

Their social life is of a free nature, and consequently but few marriages take place among them. The women are vulgarly called gatas (cats), or garbanceras (bastards); the former are those who usually perform the offices of chambermaids, nurses and cooks, the latter generally do the marketing.

As the shops where the marketing is done are kept by the common people, when a marchanta (customer) appears, the shopkeeper begins to pay her compliments, and say things with double meanings. She usually answers in the same manner, which causes the shopkeeper to laugh. If the servant is at all attractive, and the clerk understands that she is a match for him, and sees that she receives his compliments with pleasure, he takes her basket, keeps on talking to her, and tries to keep her as long as possible. They carry on something like the following dialogue by the clerk saying to her:

"Que cosa se le ofrece, mi vida?" (" What do you want, my life?")

"No se enoje porque hasta eso sale perdiendo” ("Don't get mad, for you will only be the loser").

“No Ie importa, anda dispacheme," she replies ("Mind your own business, come wait on me").

"Pues deme la mano y digame como se llama" ("Well, give me your hand and tell me your name"), he rejoins.

Her reply to this is full of stinging sarcasm, which finds vent in the following way:

"Ora si! que encamisado, tan igualado! Parece que soy su juguete. Anda dispacheme y no esté moliendo que se me hace tarde y la niña me regaña porque me tardo con el mandaao" ("Well, I should say you were a naked upstart. One would think I was your plaything. Come, wait on me, and don't bother me, for it is getting late, and the mistress will scold me for being so long doing the errands").

When he sees she is a little angry, he gives her back the basket with the things she has bought. She then throws the money to him on the counter, in an angry manner, for him to take out the cost of what she has bought. When he gives her back the change, he takes her hand, which she pulls away, after he has given it a squeeze. The next day she returns to the same shop or stand, but this time she presents herself a little less reluctantly than before, and without minding at all what is said to her. On the contrary, she leads him on, by throwing little stones at him or giving him a sly pinch.

At the end of a month or two they make an appointment to meet where they may take advantage of the opportunity to treat of their love affairs more freely. The day, hour and place being appointed, by means of which they can see each other alone (which is the first object of all lovers), they get permission from their employers, and dressing themselves the best they can, hasten to the trysting place.

The first time they look at each other they are somewhat disconcerted, and try to pretend indifference. But she is not so severe in her manner but that he feels authorized in venturing on a caress. From that time he thinks it proper that she should not serve any longer where she has been, although she has been giving him a part of all her wages. In reply she says she "does not want to lose her peace of mind, because men always say the same thing to women, and she does not want him to repent by and by and put her out into the street." But at last she adds, "If you will not forsake me and will treat me kindly, I am disposed to love you; only you must tell my parents, and, if they consent, and your intentions are good, you can rely upon my being your sweetheart."

After this, the man takes the woman by the hand or puts his arm around her and covering her with his own serape, which is the general custom, they go to some stand where things, if not of very good quality, are excessively cheap, and eat enchiladas and tamales and drink pulque.

Often the honeymoon does not last long; dissension and strife are apt to ensue, and the old story of domestic infelicity is repeated. Still, though the woman concludes her husband does not love her, if he does not use the rod, they are not so miserable as might appear.

A woman of the common people prefers a man of her own class, however poor and rough he may be, to one of a higher station, whatever offers or promises he may make her. For they still preserve the traditional aversion which the Creoles and native races have always felt for foreigners.

Among the Indians the violation of conjugal faith is more rare than in any other class of society, not even excepting the middle class, which, beyond question in Mexico, as in all other countries, is the most moral and upright.

When legal marriages occur, the parents make every arrangement when the young people have arrived at an age at which they are able to bear the responsibilities of married life. When such a case presents itself, the parents of the lover go to the house of the sweetheart, and take with them a chiquihuite (a certain kind of big basket), containing a turkey, several bottles of native brandy and other drinks, bread, ears of dried corn, and peppers of different kinds. The first time the parents of the lover go to ask for the girl's hand, they organize a sort of procession, composed of some of the relatives and friends of the family and a band of music, which plays without intermission from the house from which they start to the dwelling of the maiden.

Once there, the band and the rest of the procession are profoundly silent, while the petition is being made.

The first request is generally refused by the parents of the girl, until they consult with the relatives and ascertain the will of her who is sought in marriage. If the result is favorable, they appoint the wedding day; if unfavorable, the answer is reduced simply to returning the basket with its contents.

As soon as the news in the affirmative is received, the family of the bridegroom invite all their friends to the fandango which is given on the day of the wedding, in honor of the newly-married couple. The bridegroom appears in pantaloons and short jacket of cashmere, white embroidered shirt, red sash, raw hide or deerskin shoes, and a highly decorated, broad-brimmed hat. Followed by his family, padrinos (those who are to give him away), witnesses, and those who have been invited, he proceeds to the house of the bride, where he is overwhelmed with attentions from the family.

The dress of the bride consists of a blue skirt with red sash, and a chemise with a deep yoke and sleeves elaborately embroidered with bright-colored beads, a red silk handkerchief with points crossed in front, and held by a fancy pin. The handkerchief serves to cover the neck and breast, leaving the arms free. She also wears many strings of beads, and silver hoop ear-rings of extraordinary size. Her hair is worn in two braids, laid back and forth on the back of her head, the ends tied with red ribbons. She wears babuchas, a kind of slipper made either of deerskin trimmed with beads or of gay cloth. The toilet is completed with a white woolen mantle, cut in scallops trimmed with blue, and hanging from the plaited hair.

After they have proceeded to the church and have been married according to the usual religious ceremony, they go to the house of the bride, accompanied by the greater part of the inhabitants of the village where the marriage has taken place, followed by sky-rockets, music, and shouts from the boys. In the house there is a large room decorated with wreaths, flowers, and tissue-paper ornaments, with palm-leaf mats and wooden benches running around the room. Here the wedding feast takes place, presided over by the bride and the madrina (the one who gave her away), who sit on the mats at one end of the room, while the bridegroom and his padrino, and other guests, occupy the wooden benches. There they receive the congratulations of relatives and friends. But before the dinner, the bride removes her wedding finery, and puts on a house dress, and grinds all the corn that will be necessary to make the tortillas for the repast.

When the dinner, which generally takes place about six o'clock, is over, the dance begins, accompanied in its motions by songs which, though agreeable, are somewhat melancholy. The older guests remain at the table drinking pulque and recalling their youth, until this cheerful beverage reconciles them to the epoch in which they live. The greater part of the night is spent in this way.

The following day they repair to the house of the bridegroom, where the feast is concluded with another dinner and dance; the only difference being that on this occasion the bride has nothing to do with the preparations.

The two days which are devoted to the solemnization of the wedding being spent, the couple receive the blessing of their parents and retire to their own house to enjoy the honeymoon.

The following is a specimen of a street conversation between a man and woman of the common people.

Says the man: "Pos onde va mi vida, pos de donde sale tan linda como una rosa? ni siquiera habla?" ("Where are you going, my life? Where do you come from as nice as a rose? Don't you want to speak to me?")

"Pos ande habia de ir? Mire que pregunta!" ("Where am I going? Listen, what a question!"), she replies.

"Pos claro onde va? ò ya porque lleva su rebosito nuevo se la hecha de lado!" ("Well, that's all right, but where are you going? Now that you have on your new rebozo, you are beginning to put on airs!"), he retorts. At the same moment he catches her by the rebozo.

"Oh, suélteme, mire que aburricion con V. todos los dias que lo encuentro me ha d'estar moliendo! Caramba con V.?" ("Oh, let me alone! what a nuisance you are! Every day I see you, you bother me so! Goodness, what can I do with you?") she vehemently replies.

"Pero no se enoje. Me quiere ó no me quiere? digame y si no me dice no la dejo ir!" ("Don't get mad. Do you love me or not? tell me, and if you don't tell me I shan't let you go"), says he, pacifically.

"Dale otra vez, pos ya no se lo dije el otro dia que no me ande molestando?" ("But didn't I tell you the other day not to bother me again?") says she.

"Cuando me lo ha dicho? mire nada mas que embustera!" ("When did you tell me that? See what a story-teller you are!") answers the man. "Bueno, si no me deja, se lo digo al gendarme que ahi viene!" ("Well, if you don't let me go, I'll tell the policeman who is coming there!") she threateningly answers.

"Digaselo, el no tiene que ver con mis negocios!" ("Tell him, then; he has no right to know my business!") says the man, insolently. And when she sees that she can't go, then she says, entreatingly:

''Que quiere? y dejme ir que se me hace tarde" ("What do you want? Let me go, now, because it is getting late").

He: "Pos ya se lo dije que si me quiere ó no!" ("I have already asked you, do you love me or not?").

"Pos yo lo quisiera pero dicen que es casado, pos para que me quiere? entonces vayase con su mujer!" ("I should like you, but I was told that you are married; if so, what do you want with me? Go on to your wife!") she replies.

"Miré nada mas lo que son las jentes de mentirosas. Quien se lo dijo? Si fuera casado, no la quisiera, pos digame nada mas" ("See what story-tellers the people are! Who told you? If I was married, I wouldn't love you. Only tell me"), he retorts.

"Bueno, que deveras me quiere?" ("Weil, is it really true that you love me? ") she now pleasantly replies.

"Pos hasta la paré d'enfrente, como no? V mas dulce que un acitron y mas buena que'I pan caliente. Qualquiera sénamora de V. nada mas con que se le quite un poquito el genio de Suegra que tiene, entonces si valia la plata, pero no tenga cuidado que yo se lo quitare!" ("I love you about as much as that wall in front of us. Why not? You're sweeter than preserves or candy, and better than hot bread. Whoever sees you will love you, only you must leave off some of that hot temper such as mothers-in-law have, and then you'll be equal to a silver mine; but never mind, don't bother yourself, I'll get all that out of you!")

After this, her hot temper gets the better of her, and, tossing his hand from her shoulder, and releasing the rebozo, she says:

"Déjeme! déjeme! " ("Get out the way, and let me alone!"), and. wrapping her rebozo more tightly about her head, passes rapidly from his sight.

Under ordinary circumstances, the common people are easily controlled, but if anything occurs suddenly to rouse their slumbering wrath or animosity, every animate object had better retire before the advancing frenzied multitude. Face a stampede of buffaloes—jump into the raging sea, or risk the relentless cyclone—but always keep clear of a Mexican mob. Let their anger be aroused at a bullfight because of the inefficiency of the toreros or the tameness of the bull, the further one gets from the scene the better for him. They demolish the ring, tear down its whole interior, smash the benches and seats into atoms, and did not the rurales, or strong police force, take charge of the bull-fighters, they would be in danger of losing their lives. The mob comes down upon them like a thundering tornado.

It has been estimated that the number of people who serve in one capacity or another is about one-fifth of the common population. That part relating to the household is in a great measure an inseparable adjunct of it ; but there are also separate services that are performed by people on the outside, who come daily for the purpose. The low wages, and the generally poverty-stricken condition of the masses, place the servants in a state of extreme dependence.

An average house in the city has from ten to twenty servants, and I have seen some grand houses where thirty or thirty-five were employed. Each one has his or her separate duties to perform, and there is no clashing and no infringement one upon the other. A larger number of Mexican servants can live on peaceable terms than those of any other nationality. It is a rare occurrence to hear them quarreling, whatever disaffection may exist.

The leading servants of the household may be classified as follows:

El portero—The man who takes care of the door.

El cochero—The driver.

El lacayo—The footman.

El caballerango—The hostler.

El mozo—A general man for errands, etc. (I have given an idea of him in all his glory.)

El cargador—A public carrier.

El camarista—In hotels he is the chambermaid; in private houses he attends the gentleman of the house, brushes clothes, etc.

La recamerera—Female chambermaid, as employed in private houses.

Ama de llaves—Mistress of the keys, literally; the housekeeper.

Cocinera—The cook.

Galopina—The scullion.

Pilmama—In the Mexican idiom, piltoutli niña (mama-cargar')—The woman who carries the child out to walk.

Chichi—Mexican idiom, chichihua—Wet-nurse.

Molendera—The woman who grinds the corn

Costurera—Sewing woman.

Planchadora—Ironing woman.

The position of portero is the most responsible one about the house. Both day and night he is charged with the safety and well-being of its inmates. They are generally excellent and reliable men, and perform their duties with remarkable zeal and fidelity. In large cities he does nothing but guard the door, but in smaller towns the position of portero is often merged in that of mozo, or general man. At the capital one man will have the responsible care of a large building, in which perhaps ten or a dozen families reside. They all look to him for the safety of their rooms or apartments. He lives with his family in some dark little nook under a staircase, or, if the house is so arranged, he may have a comfortable room with a window on the street or patio.

A Mexican lacayo in his picturesque hat and faultless black suit, elaborately trimmed with jingling silver, is indeed a "thing of beauty and a joy forever," but not a single instance have I ever heard of a señorita's eloping with him: the difference in station is never overlooked when it comes to matrimony.

These servants have deep attachments for the family with whom

PETATE, JARANA AND POTTERY VENDERS.

they live. They sometimes serve in one a life-time, and when no longer able to do so, are succeeded by their children, in the same capacity.

In case of a death in the family where they are employed, they at once don the somber luto (black), and never appear outside the house without it for six months.

This faithful attachment is especially and frequently shown by the pilmama. She will tenderly and patiently nurse each child in rotation, and to the last one her devotion is unimpaired. She also takes charge of baby's clothes, and herself washes the dainty fabrics, rather than intrust them to a lavandera. Children have their own pet name for the pilmama, abbreviating it into nana, Quiero mi nana" ("I want my nana") being frequently heard. The chichi (wet-nurse) does nothing but give sustenance to the babe, and is never permitted to leave the house except under the surveillance of the ama de llaves.

This latter functionary has entire charge of the household linen. She directs the army of servants under her, and is a kind of queen-bee in the hive. She holds herself far above the servants, will carry no household packages, and is very tenacious of the dignity attaching to her position. Indeed, it not infrequently happens that she is a relative or connection of the family. She has frequently three or four assistants.

Mexican servants as a whole are tractable, kind, faithful, and humble. They shrink instinctively from harshness or scolding, but yield a willing obedience to kindly given orders. They are accused of being universal thieves, in which accusation I do not concur, although, indeed, the extremely low wages for which they work might seem to warrant, or at least excuse, small peculations. But they have this redeeming trait, that they generally appreciate the trust placed in them, and this sometimes to a remarkable degree. Instances were not uncommon during the days of revolution when porteros, mozos, and other servants voluntarily sacrificed their lives in defense of the life or property of their employers. But they have their peculiarities, acquired and engendered by the various circumstances that have hedged them about, for which all allowance must be made. If due patience and tact be exercised in the outset by foreign housekeepers, they will surely become deeply attached to the entire household, and better servants are not to be found. Especially is this true with regard to American children, to whom they become extremely devoted. But it must be remembered that their customs are overgrown with the moss of centuries, and care must be exercised in disturbing it by foreign methods of labor, or the application of new ideas. They know their own way, and have a repugnance to any interference with their precious "costumbres."

In their various employments their deportment is of the most quiet kind. If the mistress desires their attention, unless near at hand she does not call their names, but merely slaps her hands together, which attracts immediate attention. This clapping is practiced in the street as well as in the house. Nothing would sooner confuse a servant than calling her name in a loud, harsh key.

On the frontier the mistress is known as señora, but in interior towns and cities she is always the niña (child), no matter if she has reached a hundred years.

The hand motion by which a servant is summoned is the reverse of our beckoning sign—the palm being turned outward.

The wages of a cook are from $2.00 to $5.00 per month; coachman, from $10.00 to $30.00; serving women, $3.00 to $8.00; and so on in like proportion.

With these small sums entire rations are not furnished them. They are paid a medio and quartillo each day, independent of their wages, to buy coffee and bread in the morning, and bread and pulque for each dinner and supper; or they are paid 62½ cents every eight days, for this purpose. In some places a medio's worth of soap is given them each week to have their clothes washed, and the lower the wages, the less soap they get. The value of this soap is often collected a month in advance, thus leaving a glaring deficit in their clean clothes account. They generally leave the last place in debt, which is assumed by the new master. If the servant's wages be $4.00 per month, and she owes $12.00 or $25.00, as the case may be, she draws only $2.50, leaving $1.50 for her abono (amount of indebtedness).

A singular method of keeping accounts is that employed by the untutored common people. I saw an Indian on the line of a certain railway who had engaged to furnish goats' and cow's milk for the contractors. The cows' milk he purchased from another party; the account with the railway and that with the party from whom he bought the milk were kept on a stick stripped of the bark in alternate sections. Certain kinds of notches were then cut on either side, indicating pints or quarts; other notches, straight or oblique, represented quartillos (3 cents), medios (6 cents), or reales (12½ cents), the payment for the same.

An error occurred in the settlement of the accounts, which the book-keeper did not observe, but which was discovered by the Indian, and, though against himself, he would only settle according to the notches on his stick.

Customs may vary in different provinces as to the way of keeping private accounts. At the capital the lives and "costumbres" of the servants are different from those in small towns and interior cities. I append the account of a cook at Santa Rosalia, which will give an idea of the forms called librettos there used between servant and employer. In the table given below it must be stated that X crossing the line means ten dollars, and V above the line, five dollars; O crossing the line is one dollar, while a small naught above the line is half a dollar; a straight mark crossing the line (|) is a real and a short one above the line is a medio.

By this it will be seen that "Gertrude Torres, under a certain date, agrees to cook and do whatever work is required of her in the house. She enters the house owing her former employer thirty-four dollars. Her new master assumes this debt, without which she could not have changed her place. Her wages are four dollars per month, and from this sum Don Santiago Stoppelli retains three dollars toward the liquidation of the original amount. The accompanying plates show how these accounts are kept.

The furnishing of the homes of the common people is necessarily meager; sometimes only mats laid upon the dirt floor serve for beds, or a few rudely made bedsteads and chairs, with pictures of the saints and a quantity of home-manufactured toys, constitute the outfit. They jente ordinario, but their houses are reasonably clean. One corner of the room is generally devoted to an infinite variety of pottery suspended on nails, This is collected from all parts of the country, and is their chief household treasure; even small children can point out the different kinds and tell where each piece was made.

Let one enter when he will, he is sure to be greeted politely, and to have the kindliest hospitality extended to him. I remember one of the houses into which I went where a pretty young woman of twenty years sat crocheting, while the baby slept in his petate cradle and the husband lay sick on his humble cot in the corner. She cordially welcomed me, and when I was seated, he, though feeble and trembling, raised himself upon his elbow, tendering me the hospitality of his pobre casa; then asked his wife to prepare for me a cup of coffee or chocolate, which she did.

I condoled with him on his illness and hoped would soon be well. To this he replied he hoped so, but as he had consumption, there was little chance for his recovery; but if it were possible, he would like to get well, "in order to serve me the rest of his life!"

I was agreeably surprised to find so many sewing machines, and that the women understand their use quite as well as we do. A machine agent informed me that the women of this class are as prompt to meet their installments as those in any country. But the price of sewing is so very cheap—only one cent a yard—that they must do a great deal to render themselves self-sustaining.

Babies are cared for with great tenderness. They are wrapped as tightly as possible in "swaddling-clothes "until about one month old, when the calzoncillos (little breeches) are substituted, for both boys and girls. The accompanying illustration represents a girl of two months. I asked the mother if it were girl or boy. "Mujer" ("woman"), she answered, "Felicita Rodriguez criada de V." Never was there a more delighted mother than when I asked her to hold the baby until its picture could be made.

The cuna (cradle) is a concomitant of every humble dwelling. It is sometimes suspended from the ceiling, but quite as often it hangs under the table. The material of which it is composed is usually palm or maguey, and its quaint little occupant looks quite comfortable, snugly sleeping in the rebozo, while the cradle sways back and forth of its own accord.

These poor women are often the mothers of such beauties as would arouse envy in the breasts of many aristocratic parents. Miguel Mondregon, whose picture is here given, was one of these children. His mother was a cook. We met him in the street in Tacubaya on the opening of the feast of Candlemas, and when I asked his name, he gave it, taking off his hat, as seen in portrait, which is an excellent likeness of him, and saying: "El criado de V." His style of dress is typical of his class. No urchin was ever happier than he when paid his real y medio (18 cents) to stand, hat in hand, while being sketched.

His cheeks and lips were like cherries; his mouth a perfect Cupid's bow; his complexion brown as a frijole; and his eyes great, soft, melting, glorious orbs.

Miguel Mondregon

An old woman, standing near, hearing our comments upon his beauty, remarked:

"Yes, he is a beauty now, but wait till he is twelve or fourteen years old, and he will be mas serio," meaning that he lost his spirituelle expression and became coarse and sallow. Pity it is that this loveliness is so evanescent.The evangelistas (letter-writers) have a distinct position to themselves. They subserve a valuable purpose to the great army of servants and low-class people, who, through them, carry on a correspondence with their lovers. With a board on his knees, or perhaps sometimes a plain little table, and a big jug of ink, and pen behind the ear, the evangelista is ready to serve his customers. Anxious lovers stand around awaiting his leisure, the desire to transmit their sentiments making his services in high demand. Note paper, variously shaped, is at hand, and for a medio or real, a letter is furnished that will be expressive of grief, jealousy, love, and overweening affection.

Love-letter written by "un evangelista."

Apreciable Señorita.

Quisiera tener el lenguaje de los angeles; la dulce inspiracion de un poeta; ó la elocuencia de un Ciceron, para expresarme en terminos dignos de Vd. Pero por desgracia mi mente la cubre el velo de la ignorancia, y no puedo menos que tomarme la libertad de revelar a Vd. mis aficciones; pues desde el primer dia que tuve la dicha de conocer a Vd., la calma ha huido de mi, y dominado por la pacion mas violenta, me adverbio a decir á Vd. que la Amo, con el amor mas puro y berdadero, y que aun me parece con ésta declaracion que hago a Vd. de mi amor, que no supera el ardor que mi triste y afligido corazon sufre, mientras tanto obtengo la contestacion de Vd. quedo impaciente por saber el fayo de vida ó de muerte que dé Vd. a. su apasionado.

Es cuanto le dice á Vd. quien á sus pies besa.

Manuel Gomez y Suarez.

[Translation.]

Esteemed Señorita.

Would that I possessed the language of the angels, the sweet inspiration of a poet, or the eloquence of a Cicero, that I might then express myself in a manner

worthy of you. But alas! my intellect, my brains, seem veiled in ignorance, and I cannot resist taking the liberty of revealing my love, my affection. When I first had the happiness of meeting you, my peace of mind fled, and governed solely by the most violent passion for you, I dare tell you I love you, with a love most pure, most true, and notwithstanding this declaration of my love you will not even then realize what my sad, afflicted heart suffers until your answer reaches me. I impatiently await your fiat, whether of life or death, to your devoted, passionate one.

Meanwhile I say to you, that I kiss your feet.

Manuel Gomez y Suarez.

A character which must be considered in the light of a nuisance, is to be found in both sexes all over the country. Plausible and gifted with all the "suavidad en el modo" of their betters, they ply their vocation in the street, as well as in private houses. If in the street, they come upon you unawares. Suddenly brown fingers are thrust under your nose, holding a comb, a toy, jewelry or a piece of dry goods or embroidery. You dare not even look at it, or feign the least knowledge of their presence, for if you should do so, they will haunt and pursue you for squares without ceasing. Enter a store, and be ever so much interested in the purchase of some article or textile fabric, here comes the irrepressible vender and again puts the article in your face, this time with a great reduction in price.

Another class with which strangers are sure to be annoyed, are the women with black shawls drawn tightly about their heads and faces; neat calico dresses, cat-like tread, though invariably in a hurry, and with the most benignant expression on their countenances. If in your house, they approach you most humbly, with many kindly inquiries after the health of the family in general, and as to how the night has been passed. While doing this, the shawl goes slightly back, revealing some article of needlework, a handsome shawl, silk dress, or whatever else they may choose for gulling you. A long history of the article follows, ending by a high price being asked for it. You don't want it, so the price is reduced until perhaps you look a little more inclined; but at last no sale is effected. She goes away apparently much disappointed and almost with tears in her eyes. But be patient! she will come again with softer tread, and with such honeyed words as will surely win their way.

She makes her appearance the second time with a handsome tray in hand, on which rest several kinds of tempting dulces. These she tells you have been sent by Doña So-and-So, also naming the street;

CRADLE OF A POOR BABY.

that she has heard you are a stranger, and sends these as a token of her regard.

Nothing remains but to accept them with many thanks for her interest, and the hope that she will soon call on you.

The next day the thoughtful woman again enters, with a humility of manner that even Uriah Heep could not excel. She makes all manner of inquiry as to the health of each inmate of the household. She then states that it was a mistake about the regalo she had brought a day or two before (of course you have long since eaten them); that the Doña told her to sell them at a certain house, and she had made the mistake. You ask her the price, that being the only alternative, and it is a startling one. She is paid, and perhaps never again appears in your house, but she has amply paid you off for not buying the first article she offered.

Happily these people do not exist in great numbers, and, though incorrigible wherever found, strangers soon discover their transparent tricks.

The rebozo is the boon of all these women, as they can carry securely concealed any number of articles without being detected by human eyes.

The rebozo also often assists in making the head of the wearer assume a ludicrous shape. Take a rear view, as the women sit cuddled up in groups of several dozen, or even hundreds, on the celebration of some feast, and with the flickering lights of a thousand torches dancing over their tightly drawn head-gear, the resemblance to a school of seals, with their heads peeping out of the water, could not be more perfect.

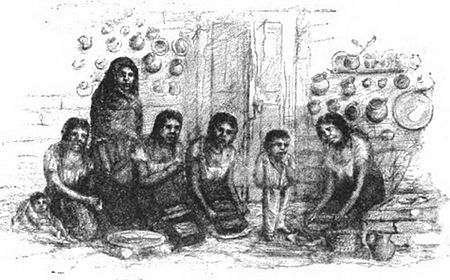

The molendera is a woman who does the grinding on the metate, whether corn for tortillas, coffee, or spices. Should the molendera set up an establishment of her own, and make tortillas for sale, or, as is sometimes the case, go at certain hours each day and make them for families, she then becomes a tortillera.

These tortilleras are a separate and distinct class, and have their own rules and regulations for conducting business. They employ ten or a dozen women, who grind the corn and make the tortillas. When made, the women who sell them in the markets and streets come with their baskets and take them away, paying wholesale rates.

The proprietress of the establishment is called the patrona, and the Queen of Sheba never moved about with more dignity and consequence.

She pays her employés each day a real y medio, I have made it convenient to drop in at the hour for settling up with them. She has a little chair or stool before her, herself unostentatiously occupying the space in front of it on the floor. The real in silver, and six cents in tlacos for each "grinder," are laid in little piles, each one being named for the woman to whom it is to be paid. The patrona sits by and looks on serenely after counting over and over the piles, with satisfaction and self-importance emanating from her, and expressing in unspoken language—"You poor contemptible ”grinders” you have no position!"

Jay Gould, in his mansion on Fifth Avenue, when reflecting on his

A TORTILLA ESTABLISHMENT.

enormous investments, could not feel more remote from the toiling multitude in the street beneath him than the patrona of the tortilla establishment feels her superiority to her subordinates.

I never went into one of these places without being most cordially invited to be seated. On accepting the invitation, an animated conversation would follow, while eating the delicious hot tortillas, fresh from the smoking comal, and admiring the animated bronze statuettes that ambled and capered about without even the disguise of a fig leaf.

Invariably they desired to know my nationality. If I told them to guess, they were sure to say France, Andalusia, or Spain, but "an American never!"

The portrait of Gregoria Queros represents one of these functionaries, and also the pure type of an Indian that she is. One might easily imagine her to be the mother of a hero, not only by her face, but also by her conversation.

On entering her house, she began by asking the usual question, and guessing I was from France. But when told I was an American, she turned her head doubtfully to one side, as if in reflection. The silence was broken by my asking her:

"What do you think of the Americans!" and the somewhat startling reply came:

"Los Americanos son como los Indios barbaros" ("The Americans are the same as wild Indians").

"Why do you say that?" I asked.

GREGORIA QUIROS.

"Because," she answered," in 1847, when I was sixteen years old, they came down here and fought terrible battles all over this country. Just think of Chapultepec, Molino del Rey, and Churubusco; ah! what sad days those were to us!"

"Well," I added (endeavoring to recall her from reflections so painful), "what other objections have you to them?"

"They are never satisfied. They always want more land and more money. This is what they live for."

During this interesting colloquy she preserved a politely respectful demeanor, and felt evidently pained to be compelled to tell me such absolute truths. A sharp neuralgic pain in her face brought forth a moan and a sigh, when she explained that for a whole year she had never been able to go for one day without the handkerchief on her head.

I asked her if she knew President Diaz.

"Who? Porfirio? I don't know him personally, but he has the reputation of being a very good and brave man; but—he has already been married twice."

I could only infer that his bravery and courage would vanish, if he should ever try matrimony again. I never found either a man or woman of that class, who spoke of the president by any other than his Christian name.

The lavandera is an important outside servant. Owing to the construction of the houses, in part, and to the fact of the water being conveyed to them from the city fountains, washing is rarely done on the premises.

The lavanderas also have their own rules and regulations, and are as rigid in exacting the observance of them by their subordinates and satellites as any other class.

In some cities and towns the lavandera is not also the planchadora. She does not even starch the clothes, but is supplied with soap for the washing. At those places presided over by a patrona, the contract is taken for all, but the custom is to charge by the piece and never by the dozen. But in the smaller towns and cities she will receive a real a dozen for washing alone, having soap furnished.

When she returns them, the planchadora comes, counts, and, on being supplied with starch and coal or wood, again takes them away to finish the job. There is, however, an agreeable offset to all this—the planchadora is also the apuntar; she mends carefully every article requiring it before taking her work home. At the capital there are laundries inside the houses where lavanderas may go and rent, for a medio a day, a compartment of brick in which the water flows from a fountain. Springs usually burst from some steep declivity of the neighboring mountains, and not infrequently in the descent to valley and lowland the water circles and winds about through the adjacent trees. In such desirable locations are the spots coveted by the lavanderas. Sometimes for the distance of two miles they may be seen like a bright fringe along the edge of the stream, in costumes which would delight a painter in search of the unconventional.

On these occasions their hair is unbraided and hangs in a superb mass of rippling waves to the end. The only dress is a red woolen petticoat and the chemise, both of which serve only to enhance the classic beauty of form disclosed by the peculiar costume.

Six or seven days of the week, kneeling in graceful attitudes, these laundresses may be seen expending their tireless energy on the ropa (clothes). Armed with the crude washing equipments of the ancient Egyptians—only a stone slab, or at best a wooden tray resembling our bread-trays—they make their week's washing whiter than the whitest. However it is accomplished, the fact remains that without boiling, washing-soda, washboard, tub or bucket, and even in many cases without soap, this perplexing branch of domestic life is brought to perfection.

WATER CARRIER.

The aguador is the most noted of all the classes who serve outside the residence. As there are few houses furnished with pipes, the water supply is transported by this functionary.

His costume is peculiar to himself and well adapted to his vocation. It varies in every province. That worn in the City of Mexico is the most picturesque, and deserves a description. Over a shirt and drawers of common domestic he wears a jacket and trousers of blue cloth or tanned buckskin. The latter are turned up nearly to the knee. With his leathern helmet, broad leather strap across his forehead, called frontera (from which depends the chochocol, or water-vessel), leathern apron, and sandals of the same, called guarachi, we might imagine him to be a man in armor, so completely is he enveloped in this substantial equipment.

The piece that covers the back, and on which the chochocol rests, is called respaldadera, or back-rest; that which reaches from the waist to the knee, delantal or apron; and that which protects the thigh, the rosadera. All these pieces are fastened by means of thongs to a leather waistcoat, which serves to support and balance the large jar. Both jars are attached to straps which cross on the head over a palm-leaf cap with leather visor. It is essential that these vessels correspond in size and perfectly balance. If either be suddenly broken, the aguador at once loses his balance and falls to the ground.

On the opposite side to the rosadera he carries a deerskin pouch called barrega, adorned with figures. This pouch serves for carrying the nickel coins and pitoles, or small red beans with which he keeps an account of the number of trips he makes, being paid at the end of a week or fortnight, according to the number of beans he leaves at a house. He also keeps a corresponding "tally-sheet" with beans, and compares notes with his employer when being paid.

The aguador is a person of importance; nobody knows better than he the inner life of the household that he serves. He is often made the messenger between lovers, and when for any reason he may refuse to perform that office, the ingenious lover resorts to artifice, and by means of wax fastens the missive upon the bottom of the chochocol, and the unconscious aguador thus conveys it to the expectant fair one, who informed of the device, is ready to remove the epistle. He often wonders why the young mistress comes out so early in the morning to meet him, and that he so frequently finds her lover standing at the door of his house.

The aguador scarcely ever dines at home. His wife meets him with a basket covered with a napkin at the entrance to some house, and there, together with his children and companions, he dines with good appetite and without annoyance of any kind. Then he goes to the fountain where he is accustomed to draw water, frees himself of his jars, and stretches himself in the shade to take his siesta; or he spends the rest of the day at some pulque shop, playing a game called "rayenla" with his companions, or repeating pleasantries and proverbs to the maids that happen to pass near him, and drinking pulque. But in the midst of this monotony, they also have their days of enjoyment, their days of merriment and diversion. The feast of the Holy Cross arrives, and when day begins to dawn, they burn an endless number of rockets and bombs, which they call salva or salute.

When the sun rises, the sign of the cross has been already placed on the spring of the fountain, or in the center, if the fountain is in a public square. The said crosses are adorned with rosaries or chains of poppies and cempazuchitl. On that day the water-men bathe, dress themselves in their holiday clothes and go to dine in community, eating heartily and drinking white and prepared pulque the greater part of the day.

One of the poor waterman's joys is the Saturday of Passion Week, or Sabado de Gloria: but this day is not so animated as the former, for it is confined to strewing flowers on the water of the fountain and burning an image representing their profession.

The following account of the superstitious beliefs of the Nahoan Indians is taken from Mexico á traves de los Siglos. They had singularly materialistic views in regard to death. They believed that Mictlan (literally hell) was reached by the dead after a long and painful journey. Their hieroglyphics indicate that the dead must first cross the Apanohuaya river, and to do this it was necessary to have the aid of a little yellow dog (techichi) with a cotton string tied around his neck, which was placed in the hands of the dead. Dogs of no other color could be used, as neither white nor black dogs could cross the river. The white ones would say, "I have been washed," while the black ones rejoined, "I have been stained." These dogs were reared by the natives for this special purpose, and the techichi is that well-known favorite among perros, now called the Chihuahua dog.

After crossing the river, the dog led his master, devoid of clothing, between two mountains that were constantly clashing together, then over one covered with jagged rocks, and then over eight hills upon which snow was ever falling, on through eight deserts where the winds were as sharp as knives. After this he led him through a path where arrows were flying continually; and, worst of all, he encountered a tiger that ate out his heart, when he fell into a deep, dark, foaming river, filled with lizards, after which he appeared before the King of Mictlan, when his tortuous journey was ended and his identity ceased.

It was also a belief that when the body began this journey it must have been buried for a period of four years. In this belief it was not the soul, but the body in actuality that made the mysterious journey.

For those who enjoy euphonious names, I will state that the name of the last stopping place was "Izmictlanapochcalocca, on which the alligator Xochitonal is encountered; the alligator is the earth's symbol and Xochitonal the last day of the year, which shows the body here reached the last stage of its existence and became dust of the earth."

When the two are united we see readily the connecting link in their ideas: that at the end of a certain time the body is converted into dust, and the dead are finished forever.

The Milk Tree for Dead Children—El Arbol de Leche de los Niños Muertos, embodies another superstitious tradition of the Nahoa Indians, which was the existence of a mansion where children went after death. This was called Chihuacuauhco, from a tree which was supposed to grow there, from the branches of which milk dropped to nourish the children which clung to them. It was believed that these children would return to populate the world after the race which then inhabited it had passed away.

A CELESTIAL MONOPOLY.

The superstitions of to-day among the Mexican lower classes, though without this post-mortem materialism, are quite as strong and as closely adhered to. They are almost numberless, and the most insignificant has its own place, not to be substituted by any other. Evidences of this appear in the performance of the simplest duty. Let them begin to make a fire, and the first movement is to make the sign of the cross in the air before the range; or if about to cook any such articles as tortillas, many of them, as preliminary, make the cross and utter a few words of prayer. The moon has much to do with these fancies, and many of their individual failings are laid to the account of that luminary.

These are carried with humorous effect into the smallest minutiæ of household labors. In killing fowls, they pull the head off, then make the sign of the cross with the neck on the ground, and laying the chicken on the place, declare it cannot jump about; but I noticed they always held it firmly on the cross.

Many of them keep a light burning both day and night in their houses. In the majority of instances, the light is merely a wax taper placed in a glass half filled with water, with a little oil on the top. Beside the taper a cross is fixed.

On one occasion, I went into a tortilla establishment where were eight or ten women grinding corn, and seeing the light I asked the patrona why she kept this light burning.

"Because," she answered, "I want God and all his saints to keep this house from evil spirits. We have to work very hard all day, and when this light is burning they dare not come near."

"Do you keep it burning always?" said I.

"Yes, always; without it we would be in total darkness." Then, turning to me, she asked:

"Have you not God and saints in your country?"

"Yes; but we believe that God will protect us without the light, and we do not depend on the saints;" which ended the colloquy.

I have been at times much impressed with the seriousness and sentiment so evidently underlying these little superstitious actions. The old tamalera, the music of whose grito appears in these pages, came to our house the evening I left the capital. She released her burden from her back, and then began as usual to chat with me, her extreme age and trembling frame appealing strongly to my sympathies. When I had sung her grito over and over with her, she made the sign of the cross over the olla in which she kept her tamales, then crossed herself, saying: "In the name of the Divina Providencia may I have enough customers to buy these tamales, that I may go early to my home. I am weary of trudging these streets, and mi pobre casa is far away." Before leaving, she turned to me, and, with tears streaming down her face, placed her hand on my head and said: "Niña, you leave us to-night to go to your home, that is far, far away in another land; may the Divina Providencia take you safely there; may you find your people well, and some day before I die, may you return to us here, and sing again with me this grito!"

On the feast of All Souls, they place a table on the sidewalk containing such articles of food as their dead friends and relatives liked best—even to the pulque. When morning comes, it is, of course, all gone, and the donor is duly happy, because she imagines the dear dead ones have returned and partaken of their favorite food, when in reality, mischievous boys have consumed these precious edibles. On this day the various venders and outside help come for their gifts, just as newsboys come for their contributions on New Year's. These gifts are disguised under the name of calaveras—skulls. Each one asks in his own characteristic fashion, the paper carrier in the following verse:

"Your faithful carrier

Cheerfully presents himself.

Encouraged by the hope

Of obtaining your favor:

You who are a subscriber,

Applauded everywhere

For that sincere loyalty

With which you are accustomed to pay:

He only comes to beg you

To give him his 'Calavera.'"

In the rural districts their pharmacy consists of ground glass, beaten shells, white lead, and an infinity of herbs. Their diagnosis embraces calor y frio (heat and cold), and their therapeutics are always directed toward these two conditions. A disease quite common which these women assume to cure is empeche, a condition where undigested food adheres to some part of the stomach. To dislodge the empeche, they give white lead and quicksilver, at frequent intervals, in compound doses. For paralysis, they have been known to give blue and red glass beads, ground up in equal portions, a table-spoonful at a dose. Strange to relate, the patient recovered.

VICENTA.

"I became a doctor by my natural intelligence."

If a child is slow in learning to talk, they recommend a diet of boiled swallows. This is infallible. If he is slow about walking, his legs should be rubbed with dirt. This accounts for the fact that pelado (poor) children acquire the use of their limbs sooner than those of the higher classes.

The portrait of Vicenta gives an excellent idea of the intellectual development of these women doctors. From a conversation I held with her, I feel confident she had some believer in "Altruistic Faith" as partner in the practice of her profession; for when I asked her how she became a doctor, she coolly replied: "By my natural intelligence."