Face to Face with the Mexicans/Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII.

TO PUEBLA, CHOLULA, SAN MIGUEL SESMA, AND ORIZABA—ALONG THE MEXICAN RAILWAY.

Swiftly we sped along the smooth rails, passing numerous wayside shrines, where, in the not remote past, earnest devotees halted for a prayer as they wended their way on their knees to renew their vows at the great temple of Guadalupe. Picturesque Indian burden-bearers trotted along beside the cars, peering through the windows, now and then taking off a hat or waving a hand in salutation to some passing acquaintance.

We whirled through fields of maguey, growing in parallel lines which intersected each other. The rapid motion of the train causing these lines to successively converge and diverge, the figure of a star was constantly being presented, and I could not but be delighted in fancying I saw pictured on these distant plains the emblem of my own great State.

At San Juan Teotihuacan our nineteenth century civilization intrudes on that of pre-historic times. In this Mexican Pompeii cemented floors and frescoed walls exist whose colors of green, yellow, and red are exceedingly brilliant. A strange and complex order of architecture, with columns and frescoed stonework, is revealed, and the remains of temple, amphitheater, or monument have been partially exhumed. What grand disclosures await the

A HAY-RICK.

scientist when full explorations have been made of the buried Mecca, the ancient city, the temple, or place of sepulture of the Toltecs! The Mexican Government has now placed the exhuming of these wonderful ruins under the charge of Señor Leopold Batres, an enthusiastic archæologist, under whom the work is progressing satisfactorily.

At Apizaco we leave the main line for Puebla, distant thirty miles. The entire journey from Mexico consumes only six hours, and the dust is the sole drawback to this delightful trip. But even this discomfort is largely mitigated by passing occasionally through valleys in a high state of cultivation, where the mind is constantly diverted by new scenes and objects of interest. Among them are the peculiar corn-cribs and hay-ricks, the latter built in imitation of churches, with cross, column, and spire in the distance, almost rivaling those of stone and adobe. When at last Puebla is reached, the mind is fully prepared to take in all things new and strange. A fluent English-speaking German—interpreter for the hotel—assured us that the "Casa de las Diligencias" was the best house, and we soon found ourselves in a grand old convent, with corridors lined with gorgeously blooming plants, while the cleanly spread tables reminded us that we had left Mexico without breakfast.

The camarista, with long black hair à la pompadour, keen, beady eyes and rigid lips, presented himself to register us in a book and enroll us on the big bulletin. We ordered separate rooms, and, gathering up our luggage, he preceded us and placed all our chattels in one apartment.

"But the other room—where is it?" I asked.

"You have two beds," he answered.

"Well, but we also want two rooms," I rejoined.

Snapping his eyes, and drawing his lips more closely than ever, he muttered in a long-drawn half whisper: "Dos cuartos y cuatro camas por dos señoritas Americanas solitas! Valgame Dios!" ("Two rooms and four beds for two senoritas alone!") Then, letting his voice fall still lower, he continued: "Que cosa curiosa!" ("What a curious thing!") This man of business had evidently made up his mind that one room with two beds was the proper thing for dos señoritas Americanas solitas.

The point of difference being duly settled by the administrador, we were gratified to find in our rooms no printed rules, and that he with the pompadoured hair would have no occasion to announce, like the other camaristas, “Falta Jabon y cerillos" as both soap and matches were bountifully supplied.

It was the carnival season; and from our windows we had views of ludicrous rag-tag processions parading up and down, grotesque enough to call forth smiles from a Niobe. Before my window, in a pretty house with red-tiled front, I saw a señorita, from behind a gay awning, wave her dainty fingers at her lover on the sidewalk, where he stood at least four hours daily.

Puebla has a population of one hundred thousand, and is one of the handsomest and best-built cities on the American continent, being constructed of gray granite. It is the City of Churches—perhaps more emphatically so than many others that have received the name. The schools, colleges, and public library are upon a grand scale. Public benefactions of the highest order are numerous—hospitals for children, the deaf, dumb, and blind, for men and for women. Of the

CASA DE MATERNIDAD.

latter, the Casa de Maternidad (Maternity Hospital), the newest and handsomest, was founded by a private citizen, who left in his will the sum of $200,000 with which to build and furnish it. The material is red brick and white stone in alternate layers, and the spacious interior is exquisitely neat and orderly. Every possible comfort and convenience that could be afforded in any like institution anywhere, is here liberally dispensed.

Puebla enjoys, and justly so, the reputation of being the most cleanly of all Mexican cities. The streets, like those of Mexico, run at right angles—north and south, east and west—and are swept every morning; the sidewalks are well paved, and all have their individual sub-sewers. They are admirably drained by a slight incline towards the middle, and at every corner there is a stone bridge—a guarantee against overflow and in the rainy season the consequent inconvenience to pedestrians.

The elevation above sea level is more than seven thousand feet, but the climate is mild, and being free from dampness, is far more desirable than at Mexico.

Like every other Mexican city, Puebla has a large share of historical associations. Founded by the Spaniards in 1531, it has since that time figured conspicuously in the stirring scenes which have occurred in the country. One of the most desperate encounters that took place between the French and Mexicans was here, and in commemoration of this event has originated one of the greatest national festivals, bearing the name of Cinco de Mayo (5th of May).

This city has been called the Lowell of Mexico. Manufactories of cotton, blankets, crockery, tiles, glass, thread, soap, matches, and hats abound. Some of the latter were snowy white with silver trimmings, the prettiest I ever saw, and in such numbers that every bare head might have been covered—which I regret to say was not the case.

Puebla is called the "City of the Angels." The tradition runs that, in the building of the cathedral, when the artisans ceased from their labors at the close of the day, the angels continued the work at night. This building is the central architectural feature of the city. Bishop Foster, on his visit there, thus wrote of it to The Christian Advocate: "The cathedral itself is surpassingly grand in every respect, quite equal to its better-known and more famous rival in the national capital, and must take rank among the first twenty cathedrals in the world. It is more chaste than, and quite as costly as, its great competitor. Its chapels and shrines, arranged along its transepts, are rich in pictures, images, and adornments. Its high altar is of amazing proportions, symmetry and elegance; filling the vast and high-arched nave, it is most impressive. The choir, occupying the portion of the nave in front, is of elaborate finish in carvings and costly lattices. The vast columns and capitals are of Mexican marble, as are all the bases of the altars throughout. Everywhere the precious stones of Mexico give beauty and substantial worth to the interior of the vast pile....It comes down to us from an age which it is probable will not repeat itself....The exterior is not comparable to the interior, though of vast and impressive appearance, and of the universal mixture of Spanish and Moorish architecture, built of hewn granite, and swelling grandly above the surrounding structures."

One who appreciates the ancient in architecture will find ample

STREET IN PUEBLA.

scope for the gratification of his taste in Mexico. Wonderful masses of stone are reared with a grand and impressive simplicity, and retain their interest even when stripped by time, change, and decay of all their once florid and gorgeous ornamentation. In the last stage they are pathetic and venerable. In one of our rambles we came suddenly on a convent through which the street had been cut, and high up in the niches and recesses we saw life-sized statues and frescoes of great beauty.

We visited churches and convents, many of which are devoted to hospitals and other secular purposes. At the home of the Methodist missionary, in the old building of the Inquisition, we saw niches built like chimneys into the walls. It was horrifying to think that these were the identical places where once unhappy victims were immured in living tombs.

A better view is here obtained of Popocatepetl and Iztaccihuatl than at Mexico, the crater of the former being plainly visible without glasses, while the position of his snow-capped sleeping companion is reversed. At Puebla we have her side view from the feet, while at Mexico the head is toward the city.

Pueblanas enjoy the luxury of ice brought daily from these mountains. The ever-faithful Indian has his own unique method of transportation, and constitutes himself the ice-wagon. He first wraps the ice in straw, and then, to avoid the disagreeable results of leakage, he fastens underneath the cargo large leaves of maguey, which form a conduit. Thus comfortably equipped, these tireless creatures trot the whole thirty-six miles, between the hours of two and ten in the morning, receiving for their pains and trouble one dollar!

It was a gala day in Puebla. The venders of fruit, fancy wares, flowers, and vegetables had assembled from all quarters, in the market. A whole family from Cholula were there—the man and his wife selling vegetables. As they had bright faces, we stopped to converse with them. The usual curious crowd gathered about us, intent upon hearing every word. Questions being in order, I asked the Cholulan what he knew of the Conquest.

"Only what my forefathers have told me," he replied.

"Tell me," I said, "what they told you." He began at once, and related the entire history without a break, as handed down to him, not forgetting to dwell upon the virtues and graces of Doña Marina.

"What do you think of Cortez?" I asked.

"When he came, we were all in darkness"—shutting his eyes to suit the words; but he brought us la lus de la Santa Cruz—the light of the holy cross.

Here I saw the pretty brown-skinned Indian women of San Pablo, a village in close proximity to the city. Their dresses were of uncut manta, washed until snowy white. Kiltings began at the sides, falling in classic folds, and ceasing near the front in a broad plain space. There was no fullness in the back, which seemed to add to their ease of movement. A broad, hand-wrought, bright-colored sash, tied at the side, held the skirt in place. The chemise had a deep-pointed yoke, elaborately embroidered with various-colored beads. They wore on their heads a kind of hood, also of manta, which partly concealed their shoulders, but left in ease and freedom their exquisitely molded arms. With hair hanging far below the waist, in full braided plaits, lips and cheeks of cherry-red, eyes softly glowing, and white teeth shining, the whole twenty that we saw would have made a gorgeous picture, but my efforts to procure even one portrait were unavailing, owing to their inherited prejudices. As they passed before us in close Indian file, with hardly a hair's-breadth space between them, all stepping as lightly as sylphs, under their burdens of fruits and vegetables, each one spoke to me, and in answer to my inquiries, gave me a kindly "adios, niña."

As but little is known to the outside world of the vast resources of the state and city of Puebla, I append the translation of a letter on this subject to El Diario del Hogar, a paper published at the capital:

"Excepting the capital of the republic, Puebla is the city which has most railroad stations, there being at present six, ample and well built—namely, the Mexican; that of the line of Izucorde Matamoros; that of the Texmelucan line: that called San Marcos; that of the Carboniferous Zone; and the Urbano, or city line. In its neighborhood the city has coal on the ranches of Santa Barbara; it has the inexhaustible quarry on the hill of Guadalupe, from which have come the pavements, houses, palaces, churches, and other great or large edifices in adjacent towns. This stone is dark and of a very fine grain. Further, Puebla has a quarry on the hill of Loreto, from which is taken a soft stone called xalnenen, used in building. There is the kaolin which supplies the factories of Puebla, where are manufactured the tiles that were known as talanera. There is a very fine clay for red earthenware and brick, which supplies the potteries in the suburb of La Luz, and the eighty-nine kilns for making the Roblano brick, which is known to have the consistency of stone, and the greater part of the plain on which the city is built is of a calcareous nature. There is abundance of chalk, or marl, for making lime, and this is manufactured in more than sixty kilns which run the year long. There is also another quarry at a league's distance, whence comes in great abundance the stone called chiluca in the capital. From the river Tetlaxcuafar, which traverses the city, and from the full-flowing Atoyac, half a league away, is taken gravel in abundance, and divers sorts of sand for building purposes. Three leagues off plenty of iron is found and a large foundry is kept running, there being others for bronze in Puebla. The neighboring mountains of Ualintze, of Tepenene and Tepozuchitl furnish the town with wood and some charcoal. The city has sweet water and sulphur water, and sundry little streams which all the year nourish the farming and gardening lands.

"Besides these elements, all of which it seems almost an exaggeration to attribute to so restricted a territory, we must mention that its easy means of communication find at a distance of seven leagues the mountains of Tecali and Tepeaca, which consist entirely of translucent marble, fine and vari-colored, which is called 'Mexican onyx,' as well as other solid marbles used for pavements. These mountains of marble would suffice to build a hundred cities of the size of London, Paris, Pekin, Vienna, or New York, without including in the calculation the mountains of transparent marble of Tecuantitlan, in the district of Acatlan, whose territory covers seventy square leagues of stone-fields of divers marbles. The city of Puebla, instead of being built of dark granite, might consist of buildings of transparent marble—a city unique on the continent: it certainly has the material near at hand.

"Brief reference might be made to the resources of Puebla which may be made available at reasonable rates, by means of the easy modes of transport. The range of coal of the district of Acatlan commences at Tefeji de Rodriguez and ends at the Pacific shore in the State of Guerrero, spreading over the State of Oaxaca until it reaches Tehuantepec. To the north of the State extensive fields of coal in the district of Alatriste and that of Noreste los de Tezintlan. Native quicksilver is plentiful in the districts of Atlixco and Matamoros, and gold and silver mines are worked clandestinely. In the districts of Tecali and Chiantla lead abounds of a high grade. In Chiantla and Acatlan are iron mines, worked only on a small scale. In the district of Chalchicomula exist abandoned mines of gold and silver, the chief one being called 'La Preciosa.' In the district of San Juan de los Llanos is the famous 'Hucha,' now abandoned, and the 'Cristo.' In Tetla de Ocampo are those gold placers which formerly gave the town the surname of 'The Golden.' In the same district is the tract of kaolin which gives life to the manufactory of porcelain or stoneware called 'cuayuca.' In the district of Zacatlan one of the cities furnishes abundance of quicksilver, and another rock crystal; beyond Ahuacatlan there is a mountain, conical in shape, known as Zitlala, which in the Nahuatl tongue means 'star,' this name having been bestowed by the natives by virtue of its brilliancy, like a sparkling star, in the rays of the rising and the setting sun. This is simply one great rock crystal, whose tiniest fragments resemble diamonds. In the district of Huactunango are various mines of gold, silver, and iron, which no one has engaged to work, and in Tefiji are three crags where emeralds are found, but which the natives of the Zapoteco race have concealed from the eye of the explorer. As a specimen of these emeralds, in a little town in the district of Cholula existed one of these gems, three-quarters of a Spanish yard in length, which served as the ara, or consecrated stone, on the altar of the church. Maximilian had it in his hands, and offered for it $1,000,000, which the Indians would not accept. Later, an armed force went to attack the town, to capture this gem, which was worth more than $2,000,000, but they were repulsed. In consequence of this attempt, the Indians concluded to lose the emerald by design, to protect it from the covetous. However, that remarkable treasure found its way into the hands of the wily Jesuits. They, in order to secure it, promised eternal salvation to the dead, the living, and the as yet unborn, in the vicinity of that town, that they might obtain

STREET AND ARCADE IN PUEBLA.

"In the district of Chalchimula there are also marbles, and in A!atriste there are great hot springs superior to those of the capital of Puebla, and equal probably to those of Aguascalientes and of Atotonilco el Grande, of the State of Hidalgo.

"Treating of the vegetable kingdom, the districts of Huachinango, Zacatlan, Tetela, Zacapoatla, Tlalauqui, and Tezuitlan produce the finest woods in the world, such as the varieties of cedar, ebony, the mahogany, zapatillo, the oyametl, pine, ocotl, juniperus sabina, oak, madroño, bamboo, ayacohuite, liquidambar, India-rubber tree, and that which yields the gum chitle, and, above all woods, the writing-tree, whose veins of color upon a yellowish ground form monograms, flourished letters, abbreviated words, and a thousand capricious figures and profiles. This wood has been adjudged, at the Expositions of Vienna, Paris, and Philadelphia, the finest from the five continents. In the districts of Acatlan, Chiuatla, and Matamoros, belonging to this State, to the southward, are produced the aloe, silk-cotton tree, log-wood, tamarind, huizacha (a species of acacia), mezquit, venenillo, tlalhuate, huaje, and other woods with Mexican names, whose qualities and duration leave nothing to be desired. Some of the trees produce the most exquisitely fragrant gums, known as myrrh, incense, and copatle, besides the rich essence of the aloe. The yellow dye known as Zacatlaxcatl, so highly prized in China, Cochin-China, Tartary, and Japan, is abundantly produced in these districts and in Tecamachalco and Telmacan. The palm which is used for mats and common hats is produced in the districts of Tepip, Tepeaca, Tecali and Tehuacan; and in the last named, cactus of the most extraordinary dimensions, as well as the vine from which is made a wine superior to that of Spain and Italy. In the district of Tlatlauquitepec is raised the famous ramie, or vegetable silk, which has enriched and given a name to Asiatic India. This plant was with difficulty brought to France and acclimated in Provence, but without success as an industry. It was then brought to Louisiana in the United States, and, although acclimated, it was never successfully treated by mechanical means, notwithstanding American effort. The magistrate of the Supreme Court of Mexico, Licentiate Mariano Zavala, brought from Louisiana a small lot of ramie, which was planted and successfully developed in the village of San Angel; but his attention did not go beyond curiosity. One day he was visited by his friend, D. Manuel Ortega y Garcia, of the district of Tlatlauqui, and Zavala presented him with the plants, six in number, telling him the mode of cultivating them. Ortega y Garcia went to the little village and transplanted the plants with brilliant success. In two years his plantations contained forty thousand plants two and three meters in height, although the plant obtains no greater height than a meter and a half in Asia. Ortega knew that the treatment of ramie was impracticable by the mechanical means employed in Europe and America; therefore he studied chemical means for that purpose, and after much endeavor, he succeeded in separating the fiber and presenting to the Minister of the Interior fine skeins, dyed in three colors, three meters and a half in length, which are now displayed spread over statues in the salon of the Minister Riva Palacio and in the house of the venerable editor. Don Ygnacio Complido, who also received a gift of several skeins. The ramie propagates prodigiously in portions of our warm, moist climate, as in Cordoba, Tlatlauqui, Cuetzala, and Huachinango. When the plant is developed, the sprouts bearing four or five leaves are removed and planted a Spanish yard apart, with surety of the success of the new plantation. The ramie is little sensitive to changes in temperature, and it neither breeds nor nourishes worms or caterpillars; neither gives life to mildew or parasitic growth. Each plant produces from $1.75 to $2.25 worth of fiber, the cost of its cultivation amounting to six cents. Thus the profit is greater than from tobacco, coffee, cacao, or cotton: moreover, from the refuse fiber is manufactured fine Chinese paper, and coarse wrapping-paper.

"The State of Puebla has a variety of climates, from that which is oppressively hot to one cloudy and cold. In some northern districts are produced cotton, tobacco, vanilla, coffee, rice, sugar cane, and all the fruits of the cold zones and the hot; in the southern districts the fruits of the hot zones, cotton, tea, coffee, and the Mexican agave of the species oyamee, which produces the mezcal liquor. The best sugar plantations are in the south, and they produce molasses, aguardientes, and sugar of various grades. In this zone are the immense grazing lands of cattle, goats, sheep, and horses; the salt mines of Chiautla, Chinantla, and Piaxtla, and the purgative-salt of Chietla. In Atlixco are produced pease, rice, corn, beans, chile pepper, barley, benne-seed, and some wheat. The districts of the north yield the same products, excepting the wheat, the salt mines and the grazing on a large scale; in exchange, Zacatlan produces apple-brandy superior to the Spanish Catalan, and delicious wines from the orange, quince, and blackberry. In the central districts grows the best wheat raised in eastern Mexico, all the fruit and grain of cold climates, the mulato chile, whence comes a soda refined here, and another which is treated in France; also wool and bristles.

"The flora of this State is abundant and varied, as known to the scientific commission exploring the territory, and its products would supply the perfumeries and drug-shops of the world.

"The races and classes inhabiting Puebla are as follows: The Hispano-American, which is the principal one; the Aztec, the Chichimeca, the Tatonavue, the Cuatocomaque, the Tepounga, and the Mizteca, whose tongues and dialects to-day, as well as a great part of their customs, are of the primitive people. The capitals of the most populous and cultivated districts outside the State capital are: Tehuacan, preeminent in agriculture and commerce; Teziutlan, under the same conditions, where live some capitalists, almost millionaires. The city of Chalchicomula is agricultural and industrial, in the line of mills. Atlixco and Matamoros are beautiful, rich, and productive of utensils. Zacatlan, agricultural and industrial in the branch of liquors, and Tecamachalco, given to agriculture and milling. The garden spots of the north are: Zacatlan, with its natural beauty, its fair, lovely race, and distinguished families; Teziutlan, with the panoramas its territories offer; its people white and elegant, and the culture of its sons; Zacapoaxtla, with its florid vegetation, its agreeable, fine, mixed race, and the inclination of its sons toward literature, distinguished above all the people of the State; the inhabitants of Tetela de Ocanepo, whose people are clever and unpretentious—every one here can read and write, understands domestic history, general geography, geometry, numbers, the use of arms, and constitutional rights. In the towns forming the district of Tetela there is no Roman Catholic guild, nor is there need of a police judge, because here occur no robberies, no homicides, no quarrels, no impositions, no adulteries, nothing of crime or disorder. The Tetelanos are the Lacedemonians of the State of Puebla. The gardens of the south are: Picturesque Atlixco, watered by a hundred streams of crystal flood, with its orchards of varied fruits, its thickets of mixed flowers of loveliest hue, and withal a cultured society; Izricar of Matamoros, traversed by an overflowing stream like Atlixco, with its proud buildings, its lovely brown women, its ardent temperament, its fertile meadows, and its valuable sugar plantations, which bring enormous rental to their owners; Acatlan, land of fire, with its forward meadows, its fruitful ground-plots, its sugar-mills; its cane-fields, and its active commerce with the Pacific coast."

Tram-cars, built in New York, run in all directions from the city, some extending from ten to fifty miles, to villages, sugar haciendas, and factories. To Cholula it is but seven miles over the lovely green valley of Puebla, and in making the trip, we constantly enjoyed fresh and charming views. These included an ancient aqueduct and an old Spanish bridge across the river Atoyac, which affords water-power for factories and foundries.

We see the great pyramid of Cholula for miles before reaching it—a grand and imposing monument to the aboriginal builders! That these ready-handed Indian workers should have erected a mountain, without beasts of burden or implements of any kind, and by passing the brick from hand to hand, surpasses the calculations of all scientists.

It is built of adobe bricks of irregular size, from sixteen to twenty-three inches in length. The erection of this stupendous structure could never have been imposed upon freemen, and must have been the work of slaves or prisoners of war. According to Prescott, the base covers about forty-four acres—other authorities say sixty—

PYRAMID OF CHOLULA.

while Baron Humboldt suggests a comparison with "a square four times greater than the Place Vendôme in Paris, covered with layers of brick, rising to twice the elevation of the Louvre." The platform on the summit is more than an acre in extent.

The sides of the mound face the cardinal points; but the regularity of its outlines has been broken and defaced by time, and the whole surface is covered with the dirt and vegetable growth of ages. From this circumstance many have supposed that the elevation was not artificial, at least as regards its interior; but so far as explorations have been made, there is no reason to doubt that it is entirely a work of art.

In addition to trees and shrubs covered with vines and mosses, lovely wild flowers of delightful fragrance abound everywhere. We gathered our hands full, and pressed them on the spot as souvenirs of the Pyramid of Cholula. Relic venders in rags followed us around with a unique collection of cross-bones, pottery, idolos, and the customary bric-à-brac. We were ready purchasers, being willing to believe almost anything on this historic and pre-historic ground.

Much speculation has arisen as to the object in rearing so stupendous a work, whether constructed for religious use, or as a place of sepulture for kings and notables. A recent theory is, that it was erected for defense, as a place of refuge for an agricultural population otherwise unprotected.

According to Humboldt, "In its present state (and we are ignorant of its original height), its perpendicular proportion is to its base as 8 to 1, while in the three great pyramids of Gizeh, the proportion is found to be 1-6/10 to 1-7/10 to 1; or nearly as 8 to 5."

A table made by Baron Humboldt, relating to the proportions of various pyramids, is as follows:

Pyramids Built of Stone.

| Cheops. | Cephren. | Mycerinus. | ||||

| Feet. | Feet. | Feet. | ||||

| Height | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 448 | 398 | 162 | ||

| Base | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 728 | 655 | 580 |

Pyramids of Brick.

One of five stories in Egypt near Sakharah, height, 150 feet; base, 210 feet.

Of Four Stories in Mexico.

| Teothihuacan. | Cholula. | |||

| Feet. | Feet. | |||

| Height | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 171 | 172 | |

| Base | . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . | 645 | 1355 |

Humboldt continues: "The inhabitants of Anahuac apparently designed giving the Pyramid of Cholula the same height, and double the base of the pyramid of Teotihuacan. The Pyramid of Asychis, the largest known of the Egyptians, has a base of 800 feet, and is, like that of Cholula, built of brick. The Cathedral of Strasbourg is eight feet, and the cross of St. Peter's at Rome forty-one feet, lower than the top of the Pyramid of Cheops.

"Pyramids exist throughout Mexico—in the forests of Papantla, at a short distance above the level of the sea; on the plains of Cholula

EL CASTILLO, OR "HILL OF FLOWERS."

and of Teotihuacan, at an elevation which exceeds those of the passes of the Alps.

"In the most widely different nations and in climates the most different, man seems to have adopted the same style of construction, the same ornaments, the same customs, and to have placed himself under the government of the same political institutions."

A contemplation of this pyramid naturally led us to think of those other wondrous structures, Papantla, Misantla, and Mapilca, erected by the Totonacs, and situated between Jalapa and the Gulf coast; and also Xochicalco, Uxmal, Palenque, and others in other parts of the republic. But little is known about the famous and ancient ruins bearing the poetical name of Xochicalco, or "Hill of Flowers." This ignorance is probably due to its isolated and rather inaccessible position. The cerro (hill) is three hundred feet in height, and its summit reached by five winding stone stairways.

Crowning the eminence is the Castillo, a building measuring sixty-four by fifty-eight feet. This structure is composed of great blocks of porphyry, held together without the aid of mortar, and covered over with strange and grotesque sculpturings of men, beasts and fishes.

The origin of this unique and wonderful structure is shrouded in mystery. Who were the builders, and for what purpose it was built, none can tell. As a writer remarks, "It has outlasted both history and memory."

When we consider that the immense blocks of stone were probably all brought from great distances and borne up the hill by what means the imagination cannot conceive of, we are struck with amazement at the magnitude of the undertaking and the patience of the builders. Entirely without mechanical appliances, how they accomplished the feat of transporting and placing those huge stones, fills us with a wonder only equaled by a contemplation of its sister enterprise, the pyramids of Egypt.

The pyramid of Papantla is built in six stories, and a great stairway of fifty-seven steps leads to the top, which is flat. Strange shapes of serpents and alligators are carved in relief over the sides.

As these "peculiar people" so frequently planned their structures with some mysterious regard to "the times and seasons" and to the heavenly bodies, it is thought by some that the three hundred and sixty-six niches in the walls of this temple bore some connection with the ancient Toltec calendar.

But to return to Cholula. The deity worshiped by the ancient Cholulans was more peaceful and less bloodthirsty than Huitzilopochtli, the terrible and warlike god of the Aztecs. He was known as "god of the air," Quetzalcoatl, and in his hands was intrusted everything relating to agriculture and the arts. So happy was his reign that it

PYRAMID OF PAPANTLA.

The great pyramid or temple of Cholula was said to have been erected in his honor; and if a grander monument exists, made of earthly material by human hands, history has not recorded it.

From the apex of this colossal structure we gazed on the open plain of Cholula, and toward Tlaxcala, the "Land of Bread," whose hardy inhabitants, having first been defeated, became the fast and faithful friends and allies of Cortez. In the end this proved to be the key to Mexico. After the conquest, as an acknowledgment of their uniform good faith, the Tlaxcalans were exempted from servitude.

The little band of Spaniards, numbering only four hundred and fifty, accompanied by six thousand allies, marched to Cholula, which then had a population of two hundred thousand. They were hospitably received and supplied with provisions. But soon Doña Marina, the faithful interpreter of Cortez, discovered a plot for their destruction. Cortez assembled the caciques, acquainted them with his knowledge of their treachery, and demanded an escort on his way to Mexico. The next day thousands were assembled in his quarters, when, at a signal, the Spaniards attacked them and at least three thousand were slain. The natives trembled at the prowess and vengeance of the "white gods."

Cholula is now a mere village. Its four hundred pagan towers have long been demolished, but from the eminence where we stood I counted twenty spires and crosses on the Christian temples of the adjacent Indian hamlets.

The imagination may find full scope in contemplating this grand scene. Looking northward stands the mountain Malinche—the name given to Cortez by the Indians—brown and sere in the distance, on whose rugged and massive sides not a plant grows nor a flower blooms to break the monotony of its awful self. Popocatapetl, Iztaccihuatl, and Orizaba stand guard over the enchanted valley, their snow-white lops vying in crystal whiteness with the fleecy clouds that encircle them, while the calm, fleckless vault around and above tempers the grandeur of the view, and soothes the spirit into sweet poetic serenity. We turn from it in silence, with feelings of reluctance and regret.

Returning at sunset, we had a new source of diversion in a lively conversation with two señoritas and their mother. They gave us their names and the number of their street, informing us that there we would "find our house."

Despite its many advantages, I was surprised to find so few English-speaking people at Puebla. But, strictly conservative as it is, we traveled about, sketching and making notes as freely as inclination led, meeting only kindness and courtesy from all classes.

In this connection a pleasing little incident occurred further indicative of the natural kind-heartedness of the people. We had gone there quite alone and unattended, not taking, as we generally did, letters of introduction, preferring to travel incog. Walking on the street, I became suddenly ill, and sought relief in a neighboring drugstore. The proprietor insisted on my remaining for some time, giving me several doses of medicine, which were efficacious. On leaving, he handed me a prescription and a bottle of the medicine, and positively refused all compensation. "No," he said, "you ladies are strangers here, and alone; you shall not pay me anything."

We left with regret, which was only counterbalanced by pleasurable anticipations in fulfilling a promise to visit Madame de Iturbide at her country-seat near San Miguel Sesma.

At Apizaco we were met by Don Augustin, her son, who had come from the capital to escort us to the hacienda, distant five miles from the station of Esperanza. The carriage was in waiting, and soon the spirited team was hurrying us along over the plains. Never before had I seen the Mexican aloe or maguey in such magnificence. Its "clustering pyramids of flowers, towering above their dark coronals of leaves," lined the drive on either side, to the very door. Here we met a royal welcome from our distinguished countrywoman. Surrounded by her numerous retainers, we could easily imagine ourselves in a feudal castle of the middle ages. The illusion was deepened on seeing her two little Indian attendants, whom she had taken from the common herd and dressed as hacendados, in buckskin suits and silver buttons. I was not surprised at their satisfaction in their finery when Madame Iturbide assured me that, save the possibility of a single garment, these were their first clothes. These little brown-skinned monkeys were constantly bobbing in and out—with "si, niña" between each breath—bowing, and waiting on us with as much zeal as if on them devolved the sole dispensing of the honors and hospitalities of the mansion.

In the late evening we promenaded on the azotea while our hostess regaled us with delightful reminiscences of her life in Mexico. We inspected with the prince the whole interior working of the hacienda—visited the cows, the horses, and the finest specimens of swine I ever saw, so immense that they almost rivaled the cows.

Madame Iturbide told us that, in accordance with a long-established custom, the peons would sing at half-past four o'clock in the morning. Promptly at the hour, the recamarara awoke us to hear the song.

The place of assembling was near the family residence. The first that came, turning his face to the east, began singing, and continued until all had arrived, when they chanted in chorus,

The Alabado; or, Song of Praise to the Morning.

"Praised and uplifted (or upheld)

And also glorified

Be the divine sacrament!

Give us to-day sustenance!

Give us Thy divine grace!

And succor us, O Lord!

In the work of the day.

And thou, Mother of the Word,

Immaculate and pure conception,

I beseech thee from my heart

Not to forsake me, Mother mine."

Mrs. Helen Hunt Jackson, in Ramona, makes mention of the observance of this beautiful custom by the Mexicans in the early days of California.

We were shown that remarkable grass known as raiz zacaton, from which whisk-brooms and stout brushes for heavier uses are manufactured. The top is a luxuriant green, several inches in height, but no use is made of it, only the root being profitable. The peons employed to gather this fibrous substance call to their aid powerful mechanical appliances to remove it from the soil, so deep does it extend below the surface, and so tough are its myriad tendrils. It is exported all over the world and constitutes one of the most important products of the haciendas in this section of the country.

This hacienda, like all others, has its administrador, and an important office is his. While in many respects his duties are similar to those of an overseer, yet he differs very materially from that functionary. In the present instance the young gentleman who fills this position is a college graduate, speaking several languages, a bachelor of arts, and a justice of the peace. His accomplishments do not in the least militate against his efficiency as administrador, for he manages the estate most admirably, enjoying the utmost confidence of the family. He preferred his assured salary of twelve hundred dollars a year to the uncertain returns of the practice of his profession.

During this visit I obtained a better insight into the life of the peons than I had before known. From their evident contentment, I concluded that their condition was not, after all, so lamentable as I had imagined. If they have but little of worldly goods, they are rich in a politeness which redeems defects of face or person. In meeting a superior, their great clumsy straw sombreros are quickly removed by hard, horny hands, and the words gently uttered: "Ave Maria Santissima!" The superior never fails to perform his part of the salutation, and touching his hat brim answers, "En gracia concebida" ("conceived in grace"). If they pass twenty times a day, the same rule is observed. I was amused to see the little monkeys in the house practicing the formula.

A charming incident of the visit was a drive to the upper part of

AQUEDUCT

the hacienda, which extends along one of the spurs of Black Mountain. Don Augustin rode close beside the carriage on his beautiful Andalusian mare, Beso—"Kiss." Our way for miles lay beside the primitive aqueduct of hewn logs which for two hundred years or more has supplied the hacienda with water from mountain springs. San Miguel Sesma is one of the oldest haciendas in that part of the republic, and extends over more than twenty square miles. The sides of the mountain are covered with pines, oaks, and a variety of other woods. At every turn we enjoyed views of sublime scenery, and at the top six geographical heights were plainly visible—Orizaba, Popocatapetl, Iztaccihuatl, Malinche, Black Mountain, and, in the dim distance, Perote. We crossed a slight ravine, which, a rod or two below us, had, within a few years, deepened into a fissure of one hundred and ninety feet. To me it was almost as frightful as the Nochistongo. On descending the steep side of the mountain, the prince performed a daring feat, which exhibited his remarkable physical strength. The cochero seemed unable to restrain the mules and carriage from rushing headlong over the precipice. Instantly, and with the unerring precision of a professional ranchero, Don Augustin hurled his lasso, and deftly catching it around the step—Beso frothing and leaping—held back the wagonette all the way down.

Our delightful visit ended, we pursued our journey, the prince kindly escorting us to Orizaba. A few miles from Esperanza we leave the scorching winds, blinding dust, and perpetual upheaval of powerful column-like whirlwinds through which the cars run for some distance, and come to inviting shade and refreshing breezes, as we wind and twist about the mountains in leaving the table-lands. The descent is grandly wild and beyond the power of pen to picture, and travelers who have reveled in the beauties of Old World scenery give precedence to this. A writer on the subject said it is "as from earth to heaven—a little bit of Paradise." We remained on the platform to obtain an unobstructed view until our senses were dazed and giddy, as the brave little double-headed Fairlie engine pulled us safely, apparently on mere threads, along a lofty peak, darting through tunnels, crawling around curves, over slender bridges, at times hundreds of feet above some frightful abyss.

The pretty village of Maltrata looks white and peaceful in its snug retreat at the foot of the table-lands. We are told it is twenty miles away, but directly through it is only two and a half.

We purchased roses, tulipans, and other flowers of tropical growth for a mere song, from Indian venders, as well as orchids of dazzling loveliness, with their glowing yellow, pink, and red centers.

Notwithstanding the apparently dangerous route of this railway, I was reliably informed that no accident had ever occurred by which lives had been lost. It was under construction for thirty years, cost thirty millions to build, and has survived no fewer than forty different managements, besides time and again losing its charter by revolution; but its completion at last attained was a great boon to the republic. On its way to the capital it ascends seven thousand six hundred feet, and its length is only two hundred and sixty miles: and "this is the short and long of it."

As is the case with all railways in Mexico, whether of tram or steam, there are first, second, and third class rates. From Mexico to Vera Cruz, the first-class ticket costs $16.50—the second class, $12.50; but there are no Pullmans attached, and the difference consists in having neatly padded coaches for first class, while plain chairs in common coaches accommodate the less fortunate.

From Maltrata the foliage and vegetation assume a more tropical appearance, but there are wanting the tangled masses of vines and luxuriant growths one naturally expects to see. The heat, however, grows more intense, and when finally we halt before the pretty station house at Orizaba, everything and everybody seems wilted and panting under the heat. Don Augustin saw us safely to the "Hotel de las Diligencias"—a name which has a peculiar and particular attraction for hotel proprietors all over the country. Don Augustin gave us the desired information that the hotels had retained the names of former times, when they were head-quarters of the stages.

Orizaba has perhaps twenty thousand inhabitants, and considerable manufacturing interests. The Alameda is a quiet, shady park with an abundance of glorious flowers peculiar to the section. Among them I saw nothing grander than the sweet-scented Datura arborea—generally known as the Floripondio—hanging like snowy bells, ready for the fairies to ring; and the Tulipan vibrating in the soft breeze, like flaming banners. I had seen both of these at the capital and other points, but they are insignificant compared with those grown in the tropics.

The Zocalo, the cathedral and the market—the latter always a place of interest to me—were duly inspected. But the heat was so intense,

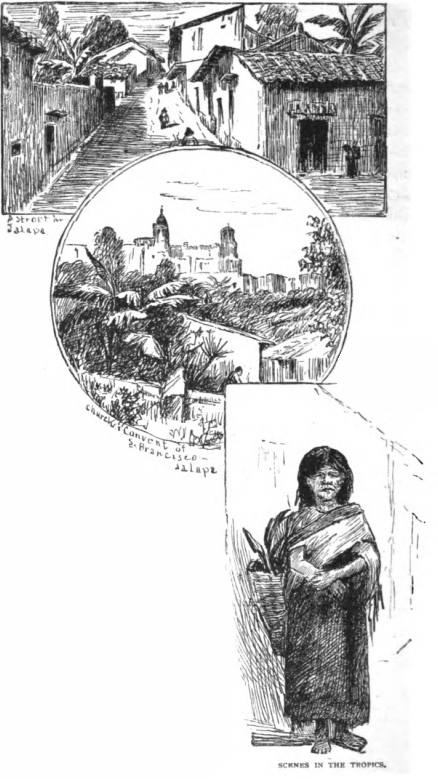

A STREET IN JALAPA.

CHURCH AND CONVENT OF SAN FRANCISCO—JALAPA.

SCENES IN THE TROPICS.

that the great quantities of fruits and vegetables lay scorched and wilted under the quaint palm umbrellas that were no more than tissue paper between them and the burning sun, and the venders had no desire to talk, and this languor had on us, likewise, a depressing influence.

With the usual number of muchachitos following with evident satisfaction all our movements, we strolled along the principal streets, across picturesque bridges, sketched and made notes by the Molino de Guadalupe, whence we caught a lovely view of a shrine of Moorish design, across a broken aqueduct, against a setting of blue in the distant mountains.

The coffee tree, with rich, dark green leaves and bright red berries—resembling cranberries—grows side by side with oranges, lemons, bananas, the cocoa-palm and gorgeous flowers, all in tropical luxuriance, overhanging low adobe fences.

The coffee berry is not allowed to ripen on the tree, but when in the red state, the branches, laden with fruit, are cut and left for several weeks to dry in the shade. After this, women and children bark it, when it is ready for shipment.

The city is walled in by mountains, and during the months of February, March, and April—as I was told by an old inhabitant—is visited almost nightly by wind storms. According to our own experience these rival the wildest hurricanes.

Our rooms were on the north or front of the hotel, consequently adapted to give the wind full sweep. Sure enough, at midnight, the tropical storm came up without a note of warning—moon and stars shining brightly in a cloudless sky—but if the Furies had been let loose our terrors could not have been intensified. Panes of glass were shivered to atoms over our heads, doors were lifted from their hinges and thrown with violence to the floor; everything movable was tossed in wild confusion, and "las dos señoritas Americanas solitas" expected to find themselves in the morning gray-headed from fright.

In the midst of the awful din and hubbub of the storm the mocking-birds on the corridor added their shrill quota to the general confusion of sounds, and I was humorously reminded of the experience of Mr. William Henry Bishop at Cordoba, when he spoke of their "dulcet ingenuity," and declared that a "planing-mill or a foundry full of trip-hammers would be a blessing in comparison."

Orizaba had now lost interest to us, and at the right hour we went to the station, expecting to continue the journey to Vera Cruz and Jalapa, but hearing a rumor of yellow fever, we decided to return to the capital.

Meeting Father Gribbin on his way from the coast, and fearing to encounter another storm at the hotel, we accepted his kind invitation to the house of his friends, Mr. and Mrs. John Quinn, who reside at Mr. Braniff's factory, four miles from the city.

The hospitality of our whole-souled entertainers was greatly enjoyed after our stormy experience of the night before.