Omnibuses and Cabs/Part II/Chapter III

CHAPTER III

The prevalence of "bilking" made the back-door cab such an unprofitable vehicle that a new style of cab became imperative.

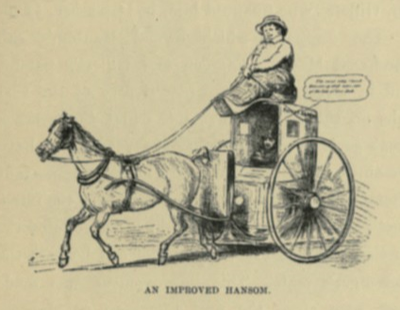

At the close of 1834, Mr. Joseph Aloysius Hansom, the architect of the old Birmingham Town Hall and founder of The Builder, patented a cab designed by himself. The body of this vehicle was almost square and hung in the centre of a square frame. The frame enclosed the whole of the body, passing over and under it. The driver sat on a small seat on the top at the front. The doors were also at the front, one on each side of the cabby's feet. The wheels were seven feet six inches in height—a trifle taller than the vehicle itself and were attached to the sides of the frame by a pair of short axles. This extraordinary vehicle Mr. Hansom himself drove from Hinckley in Leicestershire to London, much to the wonder of the inhabitants of the various towns and villages through which he passed, and to the amusement of the stage-coach drivers and waggoners whom he met on the road. Mr. Hansom, who was financed by Mr. William Boulnois, the inventor of the back-door cab, also registered another cab, the body of which resembled the one just mentioned in every respect, except that the doors were at the sides, and passengers had to enter the vehicle through the wheels, which were without felloes, naves, and spokes, the rotary action being produced by a somewhat complicated arrangement of zones and friction rollers. This cab never plied for hire in the streets, but the first-mentioned one, after the wheels had been reduced considerably in size, and one or two minor alterations made, was thought so highly of that a company was formed to purchase Mr. Hansom's rights for £10,000. An old print of this cab represents the passenger exclaiming :—

"The sweet little cherub that sits up aloft

Not a penny of the £10,000 was, however, paid to Hansom, for it was found, as soon as the cabs were placed on the streets, that they were far from being perfect.

The only money Hansom received, directly or indirectly, from his invention was £300, presented to him some time later for services rendered to the company at a critical period. But although he reaped very little pecuniary benefit from his invention, posterity has been generous in connecting his name with a cab which is far superior to the one which he invented. If the cab known to us as the "Hansom" were called the "Chapman," it would be more in accordance with historical accuracy. Mr. John Chapman, the projector of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway. was, when Mr. Hansom patented his cab, the secretary of the Safety Cabriolet and Two-wheel Carriage Company. He discovered the weak points in Hansom's cab, and, setting to work, invented a superior one. The driver's seat was placed at the back, the sliding window still in use was introduced, and the framework under the body of the vehicle was constructed to rest on the ground when tilted forwards or backwards. A cranked axle passing under the body of the cab was also introduced.

This cab was patented by Mr. Chapman and Mr. Gillett, who financed him, in December, 1836.

The company which owned Hansom's cab purchased Messrs. Chapman and Gillett's patent, and in a very short time placed fifty of the new cabs on the streets. From the first they were a great success, and for sixty-six years they have remained in public favour. The only important alteration made during those years was the introduction of the straight axle, which necessitated the cutting away of the body of the cab beneath the passenger's seat. This improvement was made very soon after the first Chapman or Hansom appeared on the streets. The side windows of hansoms were, until the fifties, very small—about one foot by eight inches.

Hansom's cab, before being improved by Chapman, bore a strong resemblance to a vehicle of which there is an illustration in Pennant's "London," published in 1790. This vehicle is represented as having just passed under Temple Bar, on which are fixed the gruesome heads of traitors. Knight mentions, in his work on London, having seen a print, dated early in the nineteenth century, of a very similar conveyance, which was described as "the carriage of the ingenious Mr. Moore". That the vehicle in Pennant was built by Francis Moore, of Cheapside, a well-known coachbuilder, there can be no doubt. The difficulty is to decide which conveyance the Pennant picture represents. The Gentleman's Magazine for 1771 contains the following paragraph: — "Oct. 30. One of Mr. Moore's carts to carry the mail, upon a new construction. was drawn to the General Post Office. The wheels are eight feet eight inches high, and the body is hung on the same manner as his coal carts, covered with wood, and painted green; the driver is to sit on the top."

Moore patented a two-wheel carriage in June, 1786, and another in 1790. The specifications of the latter show that it was hung on two large wheels. The door, however, was at the back, and the driver had a separate seat at the front, but not on the top of the vehicle. It is very probable that Hansom saw Francis Moore's carriages, and that the cab, which has made his name a household word, was an improvement upon the conveyance depicted in Pennant.

Hansom's original cabs, when not plying for hire, stood on premises which now form a part of the Baker Street Bazaar.

In 1836, hackney-coaches, "outrigger" cabriolets, and back-door cabs were still plying for hire, but the immediate and continued success of Chapman's cab prompted the proprietors of those decaying vehicles to start similar conveyances. Cabs painted and lettered in close imitation of the new patented vehicle were soon as plentiful as the real ones. Some proprietors who prided themselves on being very smart, always had the word "not" painted in very small letters before the inscription, "Hansom's Patent Safety," believing that this would save then from being prosecuted. They were mistaken, for the company made a determined effort to protect its rights, and commenced legal proceedings against the infringers of its patent. In every case the company was successful, and heavy damages were awarded it, but the victories were barren ones, for on almost every occasion the infringer of the patent turned out to be a man of straw. So when the Company had spent £2000 in lawsuits, and had succeeded only in obtaining payment of one fine of £500, it came to the conclusion that the wisest thing it could do would be to refrain in future from litigation. That was a splendid thing for the "pirate" cabs, who now dispensed with the word "not" and appeared similar in every respect to the real "Hansoms," as the Chapmans were called. When the company took over Chapman's cabs it had painted on them "Hansom's Patent Safety," so that the public might know that the conveyances belonged to the same firm as the cab which Hansom invented. And the result of this absurd action on the part of the company is that Hansom enjoys the fame which belongs by right to Chapman.

Although few people could distinguish a real hansom from its many imitators, the Company's drivers knew the difference, and treated "pirate" cabs with the utmost contempt. They called them "shofuls," and many ingenious explanations of the origin of that word have been published during the last fifty years. Some people declared that a hansom closely resembled a shovel, while others explained that two persons in a cab made it a "show full." As a matter of fact, "shoful" was a slang word for "counterfeit" among the lower class Jews, and was conferred by the many Jewish employés of the Company upon those vehicles which infringed Hansom's or Chapman's patent. In course of time it became the slang term for all hansoms, but the word is now very rarely heard.

The first four-wheeler was placed upon the streets, just as Chapman's cab appeared, by the General Cabriolet Conveyance Company. It was built by Mr. David Davies, the builder of the cabriolets of 1823, was called a "covered cab," and carried two passengers inside and one on the box seat. The doors were at the sides. This cab was quickly improved upon, and the "Clarence," our much-abused "growler," was the result. Lord Brougham was highly pleased with the new vehicle, and in 1840 he instructed his coachbuilder—Mr. Robinson of Mount Street—to make him one of a superior description. Hence the brougham.

Elderly and sober-minded people showed a market preference for riding in clarences, and hansoms soon became considered the vehicles of the fast and disreputable. This reputation has not been lived down entirely, for, at the present day, there are some old ladies who will on no account enter a hansom, and shake their head sorrowfully when they see their grand-daughters doing so. It must be confessed that hansoms figured in police-court cases much more frequently than the four-wheelers did. A well-known cab proprietor, who died a few years ago, had, in his youth, an exceedingly unpleasant experience while driving a hansom. One night he was hailed by two men who were supporting between them a sailor, who was, apparently, in an advanced state of intoxication. They placed the sailor in the cab, and then, turning to the cabman, told him to drive to a certain quiet place some distance away and wait for them there. They explained that they had a brief call to make and could not take the drunken man with them, but they would follow on in less than a quarter of an hour, and inspired confidence by paying a portion of the fare in advance. Cabby drove off and all went well until reaching a toll-gate. As the keeper came out of the toll-house he caught sight of the sailor, and, thinking that something was the matter with him, he went closer and peered into his face. Then he ran to the horse's head, and seizing it, exclaimed sharply to the cabman, "Hallo! young fellow, you've got a stiff'un in there."

"Go on; he's only drunk," the cabman replied. But the toll-keeper was not satisfied with the explanation and detained the cab until a policeman arrived. The sailor was then examined, and it was at once evident that not only was he dead, but that he had been so for several days. It was, in fact, a body-snatching job, and the rascals engaged in it had dressed the corpse in sailor's clothes to get it through the streets without attracting attention. Instructed by the police, the cabman drove to the place where he had been told to await the men, but they did not appear to claim the body. They had evidently kept a distant watch on the cab.

In the thirties and forties cabs were painted in most startling and conflicting colours, the proprietors considering, apparently, that the greater the contrast the more effective the result. A miniature white horse, symbolic of the House of Hanover, was painted on the majority of hansoms. On the sides of four-wheelers were depicted strange monsters unknown to heraldry, zoology, or mythology. These were in imitation of the armorial bearings so conspicuous on the panels of the old hackney-coaches, which, as already stated, were generally discarded family coaches.

In 1838, cabmen were compelled by Act of Parliament to take out a licence and wear a badge. On the day of the distribution of badges, many of the cabmen, attired in their best clothes, took a holiday. Some half a dozen of them walked along the Strand with their badges fixed conspicuously on their chests. A crowd soon collected around them, and in it were two Frenchmen, one apparently showing the other the sights of London. The latter inquired who the cabmen were, and an Englishman, who understood French, was surprised to hear the following reply:—

"They are gentlemen who have been decorated by the Government in honour of Her Majesty's coronation."

A new hansom, the "Tribus," patented by Mr. Harvey of Lambeth House, Westminster-bridge Road, was placed on the streets in 1844, but it was not well patronised and was soon withdrawn. The "Tribus" carried three passengers, and the entrance was at the rear, the driver's seat being removed further to the "off-side." The cabman was thus able to open or shut the door without descending from his seat. There were five windows to the vehicle, two being in front, one on each side, and one behind—beneath the driver's seat. Small safety wheels—such as can be seen at the present day attached to many omnibuses—were fixed to the front of the "Tribus" to prevent the vehicle pitching forward in the event of the horse falling, a shaft breaking, or a wheel coming off.

Mr. Harvey also patented the "Curricle Tribus," a vehicle similar to the "Tribus," with the exception that it was drawn by two horses abreast, did not possess safety wheels, and could be converted at pleasure into an open carriage. The "Curricle Tribus," however, never plied for hire.

Another unsuccessful cab was the "Quartobus," a four-wheeler with accommodation for four inside passengers. It was introduced in 1844, and Mr. Okey, the inventor, described it as "hung on four wheels, the coupling being very close for easy draft."