was claimed by Composers of every School. Nevertheless, the early Contrapuntists yielded so far to prejudice as to refrain from committing their accidentals to writing, whenever they could venture to do so without danger of misconception. Trusting to the Singer for introducing them correctly, at the moment of performance, they indicated them only in doubtful cases for which no Singer could be expected to provide. The older the Part-books we examine, the greater number of accidentals do we find left to be supplied at the Singer's discretion. Music in which they were so supplied was called Cantus fictus, or Musica ficta; and no Chorister's education was considered complete, until he was able to sing Cantus fictus correctly, at sight.

In an age in which the functions of Composer and Singer were almost invariably performed by one and the same person, this arrangement caused no difficulty whatever. So thoroughly was the matter understood, that Palestrina thought it necessary to indicate no more than two accidentals, in the whole of his 'Missa brevis,' though some thirty or forty, at least, are required in the course of the work. He would not have dared to place the same confidence either in the Singers, or the Conductors, of the present day. Too many modern editors think it less troublesome to fill in the necessary accidentals by ear, than to study the laws by which the Old Masters were governed: and ears trained at the Opera are too often but ill qualified to judge what is best suited, either to pure Ecclesiastical Music, or to the genuine Madrigal. Those, therefore, who would really understand the Music of the 15th and 16th centuries, must learn to judge, for themselves, how far the modern editor is justified in adopting the readings with which he presents[1] them: and, to assist them in so doing, we subjoin a few definite rules, collected from the works of Pietro Aron (1529), Zarlino (1558), Zacconi (1596), and some other early writers whose authority is indisputable.

I. The most important of these rules is that which relates to the formation of the Clausula vera, or True Cadence—the natural homologue, notwithstanding certain structural differences, of the Perfect Cadence as used in Modern Music. [See Clausula vera, in Appendix.]

The perfection of this Cadence—which is always associated, either with a point of repose in the phrasing of the music, or a completion of the sense of the words to which it is sung—depends upon three conditions. (a) The Canto fenno, in whatever part it may be placed, must descend one degree upon the Final of the Mode. (b) In the last Chord but one, the Canto fermo must form, with some other part, either a Major Sixth, destined to pass into an Octave; or a Minor Third, to be followed by Unison. (c) One part, and one only, must proceed to the Final by a Semitone—which, indeed, will be the natural result of compliance with the two first-named laws.

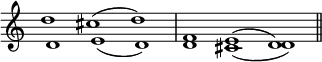

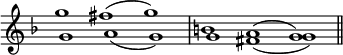

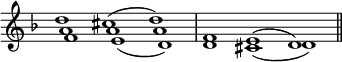

In Modes III, IV, V, VI, XIII, and XIV, it is possible to observe all these conditions, without the use of accidentals. For, in the Third and Fourth Modes, the Canto fermo will naturally tlesc~end a Semitone upon the Final; while, in the others, the Counterpoint will ascend to it by the same interval, as in the following examples, where the Canto fermo is shewn, sometimes in the lower, sometimes in the upper, and sometimes in a middle part, the motion of the two parts essential to the Cadence being indicated by slurs.

Modes III and IV. |

|

Modes V and VI. |

|

Modes XIII and XIV. |

|

But accidentals will be necessary in all other Modes, whether used at their true pitch, or transposed. (See Modes, the Ecclesiastical.)

Natural Modes |

|

VII and VIII. |

|

IX and X. |

|

Transposed Modes. |

|

VII and VIII. |

|

IX and X. |

|

Moreover, it is sometimes necessary, even in Modes V and VI, to introduce a B♭ in the penultimate Chord, when the Canto fermo is in the lowest part, in order to avoid the False Relation of the Tritonus, which naturally occurs when two Major Thirds are taken upon the step of a Major Second; although, as we have already shewn, it is quite possible, as a general rule, to form the True Cadence, in those Modes, without the aid of Accidentals.

- ↑ Proske, in his 'Musica Divina,' has placed all accidentals given or the Composer, in their usual position, before the notes to which they refer: but, those suggested by himself, above the notes. It is much to be desired that all who edit the works of the Old Masters should adopt this most excellent and conscientious plan.