Modes V and VI.

II. In the course of long compositions, True Cadences are occasionally found, ending on some note other than the Final of the Mode. When these occur simultaneously with a definite point of repose in the music, and a full completion of the sense of the words, they must be treated as genuine Cadences in some new Mode to which the Composer must be supposed to have modulated [App. p.722 "for in some new mode to which the composer must be supposed to have modulated, read upon one of the Regular or Conceded Modulations of the Mode in question."]; and the necessary accidentals must be introduced accordingly: as in the Credo of Palestrina's Missa Brevis—

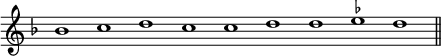

III. An accidental is also frequently needed in the last Chord of a Cadence. The rule is, that every Cadence which either terminates a composition, or concludes a well-defined strain, must end with a Major Chord. It naturally does so in Modes V, VI, VII, VIII, XIII, and XIV. In Modes I, II, III, IV, IX, and X, it must be made to do so by means of an accidental. The Major Third, thus artificially supplied, in Modes in which it would naturally be Minor, is called the 'Tierce de Picardie,' and forms one of the most striking characteristics of Mediaeval Music[1].

Modes I and II. |

|

Modes III and IV. |

|

Modes IX and X. |

|

It is not, however, in the Cadence alone, that the laws of 'Cantus Fictus' are to be observed.

IV. The use of the Augmented Fourth (Tritonus), and the Diminished Fifth (Quinta Falsa), as intervals of melody, is as strictly forbidden in Polyphonic Music, as in Plain Chaunt. [See Mi contra fa.] Whenever, therefore, these intervals occur, they must be made perfect by an accidental; thus—

It will be seen, that, in all these examples, it is the second note that is altered. No Singer could be expected to read so far in advance as to anticipate the necessity for a change in the first note. For such a necessity the text itself will generally be found to provide, and the Singers of the 16th century were quite content that this should be the case; though they felt grievously insulted by an accidental prefixed to the second note, and called it an 'Ass's mark' (Lat. Signum asininum, Germ. Eselszeichen). Even in conjunct passages, they scorned its use; though the obnoxious intervals were as sternly condemned in conjunct as in disjunct movement.

These passages are simple enough: but, sometimes, very doubtful ones occur. For instance, Pietro Aron recommends the Student, in a dilemma like the following, to choose, as the least of two evils, a Tritonus, in conjunct movement, as at (a), rather than a disjunct Quinta falsa, as at (b).

Josquin des Prés.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass \cadenzaOn \[ f2. g4^"a" a2 b \] e2. f4 g2 r2 \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/a/qarn9rzpq1vlxtmr8kmqowpo37iu8zm/qarn9rzp.png)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass \cadenzaOn f2. g4 a2 \[ bes2 e2.^"b." \] f4 g2 r \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/m/i/miir9s9g77f9cp9gm6fpt78azezqh8d/miir9s9g.png)

V. In very long, or crooked passages, the danger of an oversight is vastly increased: and, in order to meet it, it is enacted, by a law of frequent, though not universal application, that a B, between two As—or, in the transposed Modes, an E, between two Ds—must be made flat, thus—

VI. The Quinta falsa is also forbidden, as an element of harmony: and, except when used as a passing note, in the Second and Third Orders of Counterpoint, must always be corrected by an accidental; as in the following example from the Credo of Palestrina's 'Missa Æterna Christi munera.' [See Fa Fictum, in Appendix.]

The Tritonus is not likely to intrude itself, as an integral part of the harmony; since the Chords of 6-4 and 6-4-2 are forbidden in strict Counterpoint, even though the Fourth may be perfect.

VII. But both the Tritonus and Quinta falsa are freely permitted, when they occur among the

- ↑ Except in compositions in more than four parts, Mediaeval Composers usually omitted the Third, altogether, in the final chord. In this case, a Major Third is always supposed.