in which the Dominant seventh is not resolved by its passing to a near degree of the scale, but by the mass of the harmony of the Tonic following the mass of the harmony of the Dominant. Ex. 4 is an example of a similar use by him of a Dominant major ninth.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Staff \relative c''' { \key ees \major \time 4/4 \mark \markup \small "Ex. 4."

<< { r2 c | c\fermata } \\ { ees,4. d2 d8 ~ | d2 } >>

r8 g32( ees16.) ees32( bes16.) bes32( g16.) |

r8 c32( aes16.) aes32( f16.) f32( c16.)

ees4 ~ ees16[ bes] \tuplet 3/2 { aes'16 f d } | s8_"etc." }

\new Staff \relative a' { \key ees \major

<< { aes4 aes2 aes4 ~ aes2\fermata } \\ { c,8 bes2 bes4. ~ bes2 } >>

\clef bass <ees, bes g>4 r | <ees c aes> r

r8 <g bes,> q <f bes,> | s } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/e/p/ep1m3ngrsre0tey9fcs3i1aa8ej0wn6/ep1m3ngr.png)

A more common way of dealing with the resolution of such chords was to make the part having the discordant note pass to another position in the same harmony before changing, and allowing another part to supply the contiguous note; as in Ex. 5, from one of Mozart's Fantasias in C minor.

![\new ChoirStaff << \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Staff \relative b' { \key c \minor \time 4/4 \partial 2 \mark \markup \small "Ex. 5."

b8.[ f'16 aes8. b,16] | c4 \bar "||" \mark \markup \small "Ex. 5a." \partial 4 \clef treble \key f \major des4 | e, r s }

\new Staff \relative d { \key c \minor \clef bass

<d f aes b>4 r <ees g c> \clef bass \key f \major

<< { bes4 bes } \\ { g g } >> r s } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/1/71lc7jso5sb3a7ekaun9g9mvb621yzs/71lc7jso.png)

Some theorists hold that the passage of the ninth to the third—as D♭ to E in Ex. 5a (where the root C does not appear)—is sufficient to constitute resolution. That such a form of resolution is very common is obvious from theorists having noticed it, but it ought to be understood that the mere change of position of the notes of a discord is not sufficient to constitute resolution unless a real change of harmony is implied by the elimination of the discordant note; or unless the change of position leads to fresh harmony, and thereby satisfies the conditions of intelligible connection with the discord.

A much more unusual and remarkable resolution is such as appears at the end of the first movement of Beethoven's F minor Quartet as follows—

where the chord of the Dominant seventh contracts into the mere single note which it represents, and that proceeds to the note only of the Tonic; so that no actual harmony is heard in the movement after the seventh has been sounded. An example of treatment of an inversion of the major ninth of the Dominant, which is as unusual, is the following from Beethoven's last Quartet, in F, op. 135.

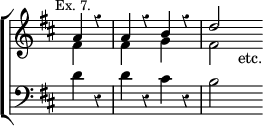

There remain to be noted a few typical devices by which resolutions are either varied or elaborated. One which was more common in early stages of harmonic music than at the present day was the use of representative progressions, which were in fact the outline of chords which would have supplied the complete succession of parts if they had been filled in. The following is a remarkable example from the Sarabande of J. S. Bach's Partita in B♭.

which might be interpreted as follows:

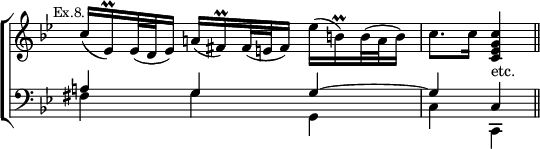

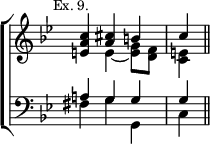

Another device which came early into use, and was in great favour with Bach and his sons and their contemporaries, and is yet an ever fruitful source of variety, is that of interpolating notes in the part which has what is called the discordant note, between its sounding and its final resolution, and either passing direct to the note which relieves the dissonance from the digression, or touching the dissonant note slightly again at the end of it. The simplest form of this device was the leap from a suspended note to another note belonging to the same harmony, and then back to the note which supplies the resolution, as in Ex. 10; and this form was extremely common in quite the early times of polyphonic music.

But much more elaborate forms of a similar nature were made use of later. An example from J. S. Bach will be found at p. 678 of vol. i,