Tri Hauner Tón. (Three half Tunes.)

The most remarkable feature in connection with Welsh music is that of Penillion singing,—singing of epigrammatic stanzas, extemporaneous or otherwise, to the accompaniment of one of the old melodies, of which there are many, very marked in character, expressly composed or chosen on account of their adaptability for the purpose, and played upon the harp. This practice is peculiar to the Welsh, and is said to date from the time of the Druids, who imparted their learning orally, through the medium of Penillion. The word Penill is derived from Pen, a head; and because these stanzas flowed extempore from, and were treasured in the head, without being committed to paper, they were called Penillion. Many of the Welsh have their memories stored with hundreds of them; some of which they have always ready in answer to almost any subject that can be proposed; or, like the Improvísatore of Italy, they sing extempore verses; and a person conversant in this art readily produces a Penill apposite to the last that was sung. But in order to be able to do this, he must be conversant with the twenty-four metres of Welsh poetry. The subjects afford a great deal of mirth. Some of these are jocular, others farcical, but most of them amorous. It is not the best vocalist who is considered to excel most in this style of epigrammatical singing; but the one who has the strongest sense of rhythm, and can give most effect and humour to the salient points of the stanza—not unlike the parlante singing of the Italians in comic opera. The singers continue to take up their Penill alternately with the harp without intermission, never repeating the same stanza (for that would forfeit the honour of being held first in the contest), and whichever metre the first singer starts with must be strictly adhered to by those who follow. The metres of these stanzas are various; a stanza containing from three to nine verses, and a verse consisting of a certain number of syllables, from two to eight. One of these metres is the Triban, or triplet; another, the Awdl Gywydd, or Hén Ganiad,—the ode-measure or the ancient strain; another, what in English poetry would be called anapæstic.

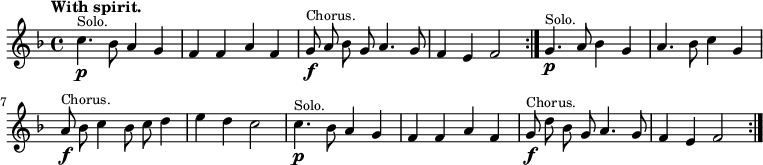

There are two kinds of Penillion singing; the most simple being where the singer adapts his words to the melody, in which case words and music are so arranged as to allow of a burden, or response in chorus, at the end of each line of the stanza, as in the following example:—

Nos Galan. (New Year's Eve)

Hob y Deri Danno. (Away, my herd, to the Oaken Grove.)

As sung in North Wales.

![{ \relative b' { \key bes \major \time 2/4 \tempo "Cheerfully." \autoBeamOff

\repeat volta 2 {

bes8\p^\markup \small "Solo" bes d8. c16 | bes8 f g f |

g16\f^\markup \small "Burden" a g f g8 f | bes4\p d | c2 }

ees8^\markup \small "Solo" ees g g16 f | ees8 c d c |

f8.\f^\markup \small "Burden" f16 f8 e | f2 |

bes,8^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes16[ c] d[ ees] |

f8 f16[ ees] d8 c | bes4 c | d8 d c4 |

f8 f16 ees d8 c | d8. c16 bes4 |

bes4\p^\markup \small "Burden" d | bes2 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/1/b1sde2t4x2olainrhbb8u7dcdf8zqri/b1sde2t4.png)

Hob y Deri Dando. (Away, my herd, under the Green Oak.)

The same song as sung in South Wales.

![{ \relative f' { \key bes \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Cheerfully." \autoBeamOff

f4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

bes8^\markup \small "Burden" d c bes c4 f, | R1 |

f4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

f'8^\markup \small "Burden" g f g f4 f, | R1 \bar "||"

f'4^\markup \small "Solo" f8. f16 f4 ees8[ d] | ees4 4 4 d8[ c] |

d4.^\markup \small "Burden" ees8 d4 c8[ bes] | c2 r |

f,4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

f bes8.[ c16] bes2 | a8. bes16 c8. d16 c2 |

bes4 f'8. g16 f4. ees8 |

d4.^\markup \small "Burden" c8 bes2 \bar "||" \mark \markup { \musicglyph "scripts.ufermata" } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/c/ncqvcbmqw789vsa4do93ydek22yye3w/ncqvcbmq.png)

The most difficult form of Penillion singing is where the singer does not follow the melody implicitly, but recites his lines on any note that may be in keeping with the harmony of the melody, which renders him indifferent as to