sians[1], among whom we find it both in literature and in art, and there is the negative evidence of no monument anterior to them representing this decoration.

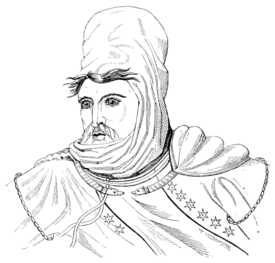

Several of these torques were deposited in the tomb of Cyrus[2], and they were bestowed by his successors as presents[3], or as marks of honour[4], and indeed were not allowed to be worn except by express permission of the king. This personal ornament may have been adopted by the Persians from their predecessors in Central Asia, the Assyrians, but it is not derivable from the Egyptians. On the staircase of Persepolis[5], the torques represented as a thick circle of twisted gold, with a break in the centre, and the ends terminating in the heads of snakes, is borne in tribute, or as an offering, to Darius I.

The Greeks, both from their literature and art, appear never to have used the torques; but it was considered a necessary part of the attire of oriental personages, and is found on the neck of Darius and his officers at the battle of Arbela, as represented in the Mosaic of Pompeii[6], and the Phrygian Atys, Anchises[7],and other Asiatics[8] wear it. In all these instances it retains its funicular or twisted type. The torques is frequently mentioned by, and was more familiar to the Romans. L. Sicinius Dentatus is stated about B.C. 386 to have had one hundred and eighty-three borne before him in his

- ↑ Josephus x. c. 12. mentions Abimelarodach promising a στρέπτον, but we should recollect the application of the same word, Septuag. Gen. xli. 42. to the collar worn by Joseph, decidedly not a torquis. Cf. Sir G. Wilkinson, Mann. and Cust. of Egypt. Ser. II. vol. iii. Pl. 80.

- ↑ Arrian. Exp. Alex. VIII.

- ↑ Aelian. I. 22. Plut. vit. Artax. Curt. iii. 22.

- ↑ Joseph, loc. cit. Xenoph. Cyropæd. 1. i. Nepos. vit. Datamis. c. 5.

- ↑ Kerr Porter's Travels. I. pl. xxxiv. sq.

- ↑ Museo Borbonico. viii. pl. 34.

- ↑ Millingen Anc. Uned. Mon. P. xii.

- ↑ Virgil, Æneid. Ovid. Met. v. f. 1. 1. 52.