1899), Théel (“Echinocyamus,” Nov. Act. Soc. Sci. Upsala, 1892), R. Semon (“Synapta,” Jena. Zeitschr., 1888), and Lovén (opp. citt.); and though the theories based thereon may have been fantastic and contradictory, we are now near the time when the results can be co-ordinated and some agreement reached. But the scattered details of comparative anatomy are capable of manifold arrangement, while the palimpsest of individual development is not merely fragmentary, but often has the fragments misplaced. The morphologist may propose classifications, and the embryologist may erect genealogical trees, but all schemes which do not agree with the direct evidence of fossils must be abandoned; and it is this evidence, above all, that gained enormously in volume and in value during the last quarter of the 19th century. The Silurian crinoids and cystids of Sweden have been illustrated in N. P. Angelin’s Iconographia crinoideorum (1878); the Palaeozoic crinoids and cystids of Bohemia are dealt with in J. Barrande’s Système silurien (1887 and 1899); P. H. Carpenter published important papers on fossil crinoids in the Journal of the Geological Society, on Cystidea in that of the Linnean Society, 1891, and, together with R. Etheridge, jun., compiled the large Catalogue of Blastoidea in the British Museum, 1886; O. Jaekel, in addition to valuable studies on crinoids and cystids appearing in the Zeitschrift of the German Geological Society, has published the first volume of Die Stammesgeschichte der Pelmatozoen (Berlin, 1899), a richly suggestive work; the Mesozoic Echinoderms of France, Switzerland and Portugal have been made known by P. de Loriol, G. H. Cotteau, J. Lambert, V. Gauthier and others (see Paléontologie française, Mém. Soc. paléontol. de la Suisse, Trabalhos Comm. Geol. Portugal, &c.); a beautiful and interesting Devonian fauna from Bundenbach has been described by O. Follmann, Jaekel, and especially B. Stürtz (see Verhandl. nat. Vereins preuss. Rheinlande, Paläont. Abhandl., and Palaeontographica); while the multitude of North American palaeozoic crinoids has been attacked by C. Wachsmuth and F. Springer in the Proceedings (1879, 1881, 1885, 1886), of the Philadelphia Academy and the Memoirs (1897) of the Harvard Museum.

The vast mass of material made known by these and many other distinguished writers has to be included in our classification, and that classification itself must be controlled by the story it reveals. Thus it is that a change, characteristic of modern systematic zoology, is affecting the subdivisions of the classes. It is not long since the main lines of division corresponded roughly to gaps in geological history: the orders were Palaeocrinoidea and Neocrinoidea, Palechinoidea and Euechinoidea, Palaeasteroidea and Euasteroidea, and so forth. Or divisions were based upon certain modifications of structure which, as we now see, affected assemblages of diverse affinity: thus both Blastoidea and Euechinoidea were divided into Regularia and Irregularia; the Holothuroidea into Pneumophora and Apneumona; and Crinoids were discussed under the heads “stalked” and “unstalked.” The barriers between these groups may be regarded as horizontal planes cutting across the branches of the ascending tree of life at levels determined chiefly by our ignorance; as knowledge increases, and as the conception of a genealogical classification gains acceptance, they are being replaced by vertical partitions which separate branch from branch. The changes may be appreciated by comparing the systematic synopses at the end of this article with the classification adopted in 1877 in the 9th edition of the Ency. Brit. (vol. vii.), or in any zoological text-book contemporary therewith. In the present stage of our knowledge these minor divisions are the really important ones. For, whereas to one brilliant suggestion of far-reaching homology another can always be opposed, by the detailed comparison of individual growth-stages in carefully selected series of fossils, and by the minute application to these of the principle that individual history repeats race history, it actually is possible to unfold lines of descent that do not admit of doubt. The gradual linking up of these will manifest the true genealogy of each class, and reconstruct its ancestral forms by proof instead of conjecture. The problem of the interrelations of the classes will thus be reduced to its simplest terms, and even questions as to the nature of the primitive Echinoderm and its affinity to the ancestors of other phyla may become more than exercises for the ingenuity of youth. Work has been and is being done by the laborious methods here alluded to, and though the diversity of opinion as to the broader groupings of classification is still restricted only by the number of writers, we can point to an ever-increasing body of assured knowledge on which all are agreed. Unfortunately such allusion to these disconnected certainties as alone might be introduced here would be too brief for comprehension, and we are forced to select a few of the broader hypotheses for a treatment that may seem dogmatic and prejudiced.

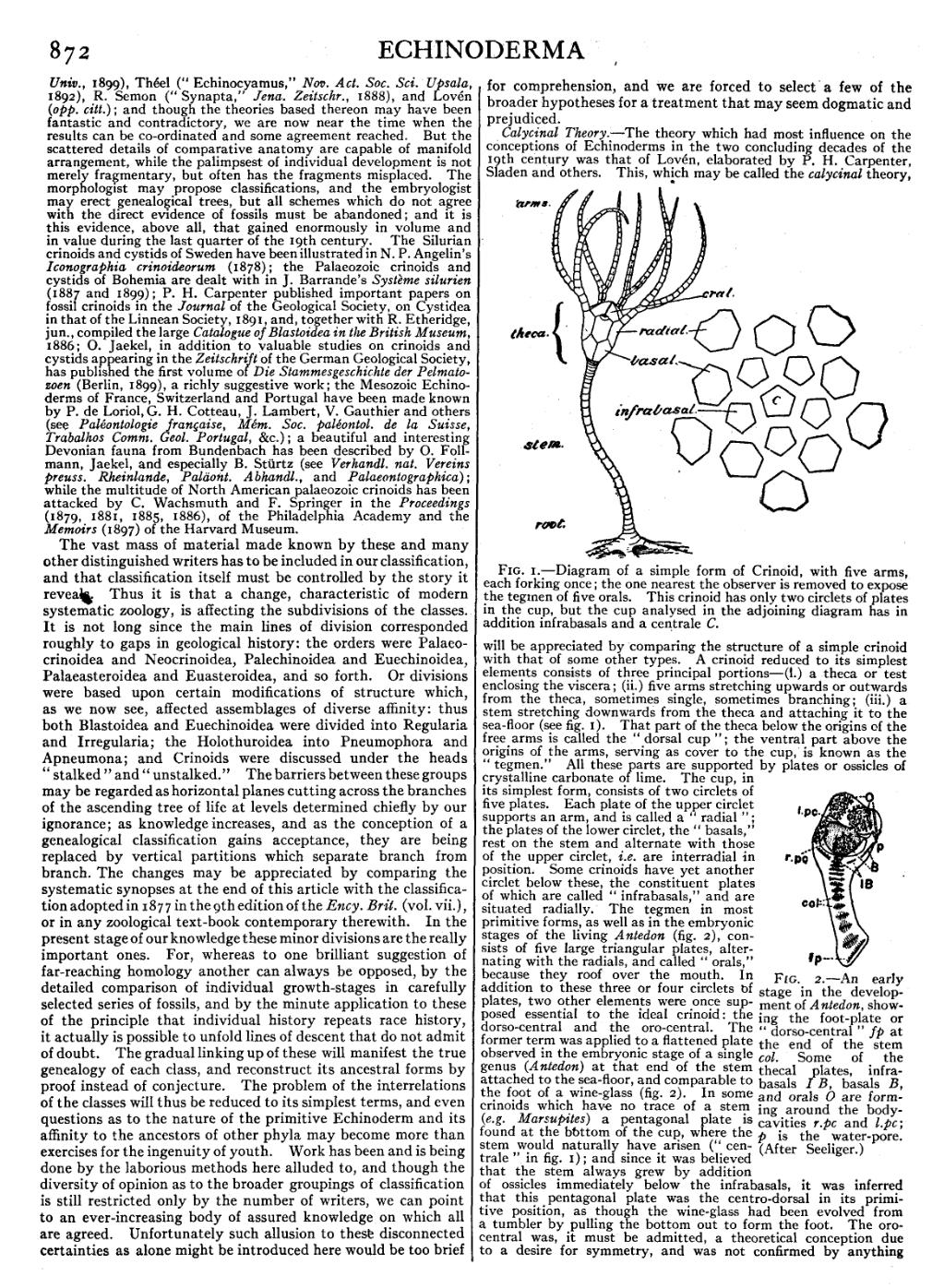

Calycinal Theory.—The theory which had most influence on the conceptions of Echinoderms in the two concluding decades of the 19th century was that of Lovén, elaborated by P. H. Carpenter, Sladen and others. This, which may be called the calycinal theory, will be appreciated by comparing the structure of a simple crinoid with that of some other types. A crinoid reduced to its simplest elements consists of three principal portions—(i.) a theca or test enclosing the viscera; (ii.) five arms stretching upwards or outwards from the theca, sometimes single, sometimes branching; (iii.) a stem stretching downwards from the theca and attaching it to the sea-floor (see fig. 1). That part of the theca below the origins of the free arms is called the “dorsal cup”; the ventral part above the origins of the arms, serving as cover to the cup, is known as the “tegmen.” All these parts are supported by plates or ossicles of crystalline carbonate of lime. The cup, in its simplest form, consists of two circlets of five plates. Each plate of the upper circlet supports an arm, and is called a “radial”; the plates of the lower circlet, the “basals,” rest on the stem and alternate with those of the upper circlet, i.e. are interradial in position. Some crinoids have yet another circlet below these, the constituent plates of which are called “infrabasals,” and are situated radially. The tegmen in most primitive forms, as well as in the embryonic stages of the living Antedon (fig. 2), consists of five large triangular plates, alternating with the radials, and called “orals,” because they roof over the mouth. In addition to these three or four circlets of plates, two other elements were once supposed essential to the ideal crinoid: the dorso-central and the oro-central. The former term was applied to a flattened plate observed in the embryonic stage of a single genus (Antedon) at that end of the stem attached to the sea-floor, and comparable to the foot of a wine-glass (fig. 2). In some crinoids which have no trace of a stem (e.g. Marsupites) a pentagonal plate is found at the bottom of the cup, where the stem would naturally have arisen (“centrale” in fig. 1); and since it was believed that the stem always grew by addition of ossicles immediately below the infrabasals, it was inferred that this pentagonal plate was the centro-dorsal in its primitive position, as though the wine-glass had been evolved from a tumbler by pulling the bottom out to form the foot. The oro-central was, it must be admitted, a theoretical conception due to a desire for symmetry, and was not confirmed by anything